#nikolai ladovsky

Text

Nikolai Ladovsky

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

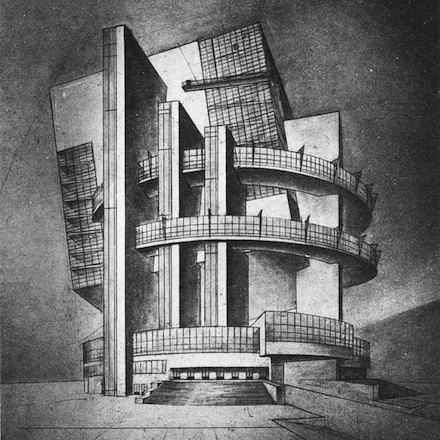

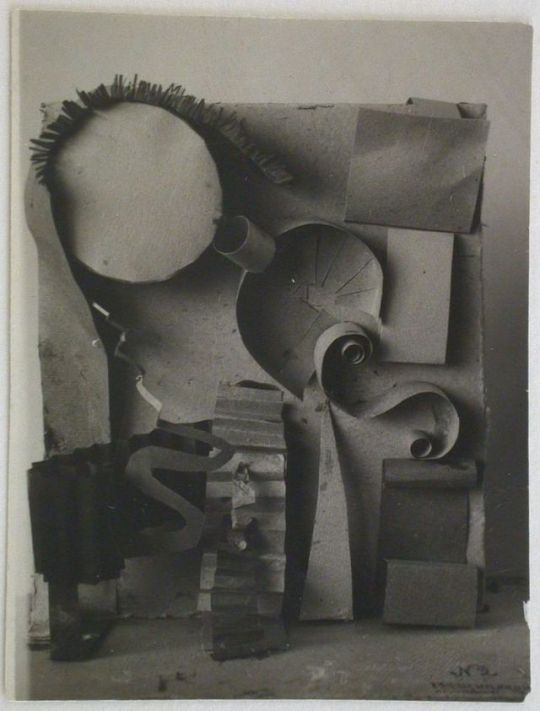

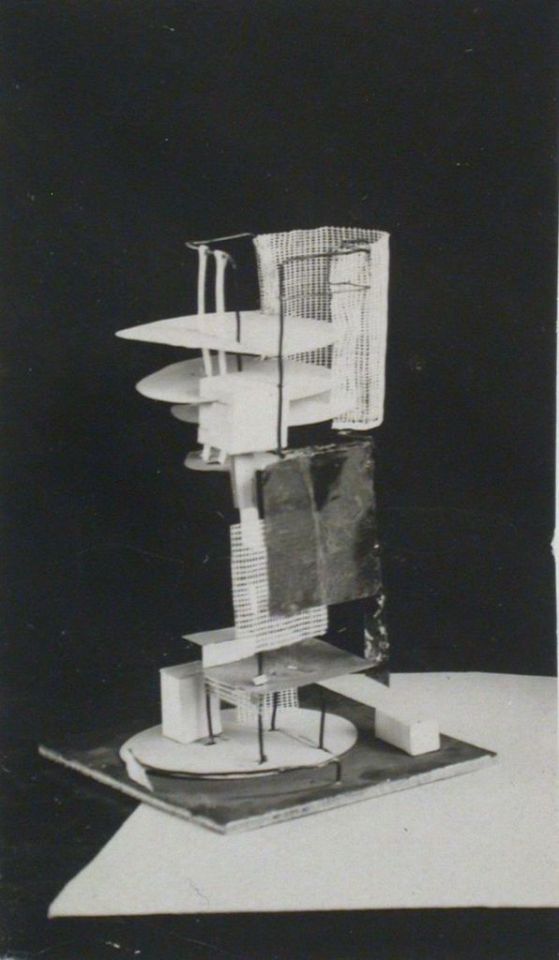

Nikolai Alexandrovich Ladovsky, Architectural phenomenon of a communal house, 1920

VS

Frank Owen Gehry, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain, 1997

#frank gehry#frank o gehry#frank owen gehry#bilbao#spain#architecture#guggenheim#guggenheim museum#guggenheim museum bilbao#contemprary architecture#Nikolai Ladovsky#russia#russian art#russian#russian architecture#collage#collage art#cut and paste#VKhUTEMAS#soviet#modernism#drawings

35 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Sculpture is an art of handling shape. Architecture is an art of handling space. Space is used by all kinds of art, but only architecture enables us to read the fabric of space correctly. Architects' material is space, not stone. Sculptural shape in architecture is subordinate to space. Graphic arts are subordinate to both space and sculptural shape.

Nikolai Ladovsky

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nikolai Ladovsky’s southern entrance to Krasnye Vorota metro station, Moscow, 1935 (via here)

#Nikolai Ladovsky#architecture#public transport#metro#station#subway#tube#underground#Moscow#USSR#Soviet Union#1930s

224 notes

·

View notes

Photo

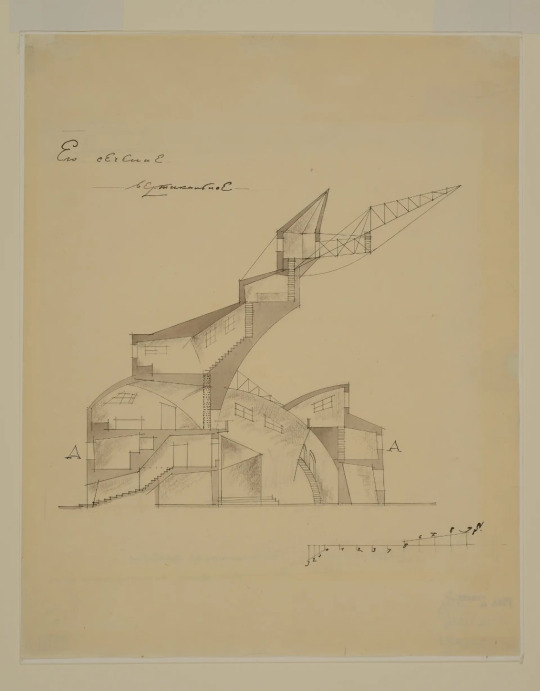

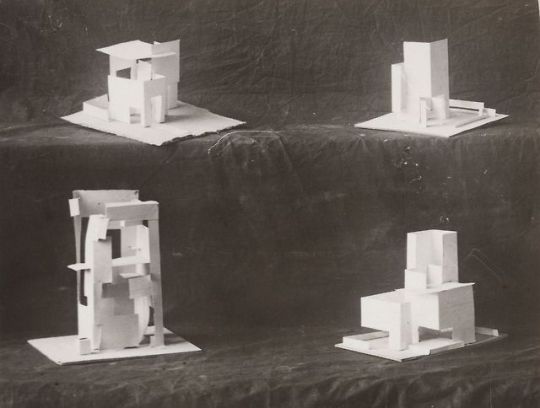

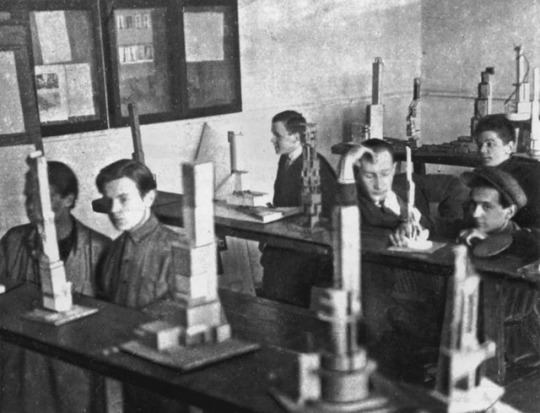

VKhUTEMAS was an art and technical school set up in 1920 in Moscow that saw itself as a realization of the new revolutionary government’s approach to art, and which was to become a vital part of building a new society. Often this ‘building’ was in the most literal sense: one of the chief skills taught there was architecture, next to industrial and technical design, textiles, painting and sculpture. This exhibition in Martin-Gropius-Bau focuses on the school’s architecture teaching, and on the highly interdisciplinary, experimental methods developed there by some of the greatest Russian architects of the 20th century, such as Nikolai Ladovsky, Moisei Ginsburg, and Konstantin Melnikov. They were able to produce such pioneering results by treating artistic education as part of a whole. Many of these architects were also fascinating painters. At the same time, few of VKhUTEMAS students’ boldest designs were built, and the school faced a political backlash as early as 1929.

https://thecharnelhouse.org/2017/12/27/vkhutemas-the-soviet-bauhaus/

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

1920s El Lissitzky life

After two years of intensive work Lissitzky was taken ill with acute pneumonia in October 1923. A few weeks later he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis

February 1924 he relocated to a Swiss sanatorium near Locarno He kept very busy during his stay, working on advertisement designs for Pelikan Industries, translating articles written by Malevich into German, and experimenting heavily in typographic design and photography.

In 1925, after the Swiss government denied his request to renew his visa, Lissitzky returned to Moscow and began teaching interior design, metalwork, and architecture at Vkhutemas (State Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops), a post he would keep until 1930.

He all but stopped his Proun works and became increasingly active in architecture and propaganda designs.

In June 1926, Lissitzky left the country again, this time for a brief stay in Germany and the Netherlands. There he designed an exhibition room for the Internationale Kunstausstellung art show in Dresden and the Raum Konstruktive Kunst ('Room for constructivist art') and Abstraktes Kabinett shows in Hanover, and perfected the 1925 Wolkenbügel concept in collaboration with Mart Stam.

"1926. My most important work as an artist begins: the creation of exhibitions."

In 1926, Lissitzky joined Nikolai Ladovsky's Association of New Architects (ASNOVA) and designed the only issue of the association's journal Izvestiia ASNOVA (News of ASNOVA) in 1926.

0 notes

Photo

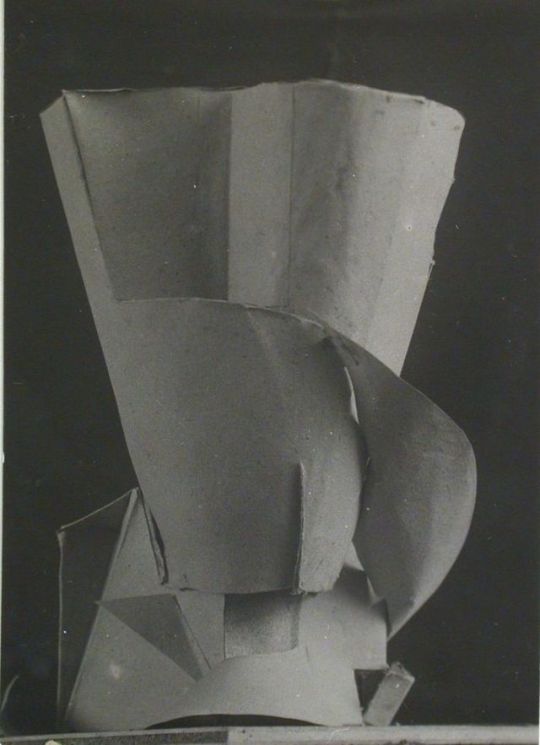

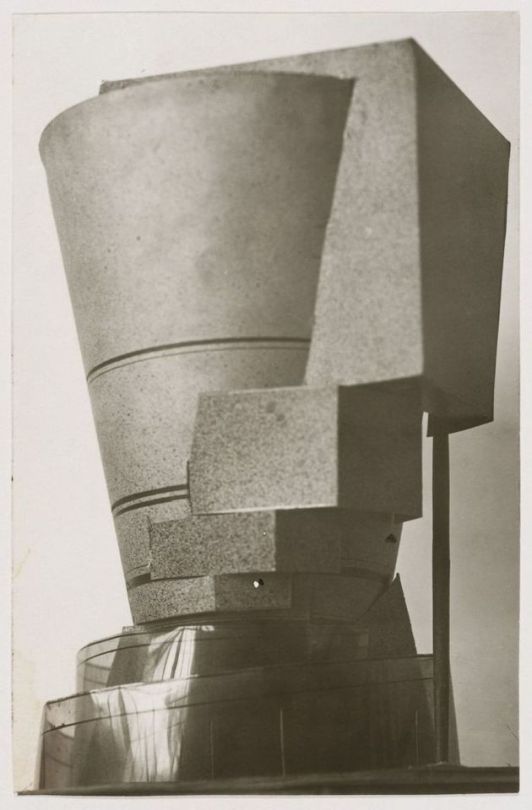

Vkhutemas, OBMAS (Nikolai Ladovsky, Vladimir Krinsky, Nikolay Dokuchaev), Space class

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nikolai Ladovsky: la casa-comuna y el método psicoanalítico de enseñar arquitectura | Jelena Prokopljević

La vivienda era uno de los grandes temas de la investigación arquitectónica desde los primeros años postrevolucionarios en la Unión soviética. La casa comuna se dibujaba como una de las mejores soluciones y se desarrollaba en dos vertientes: la reorganización de las viviendas existentes y la construcción de las nuevas. La primera suponía la subdivisión de las casas expropiadas y el nuevo repartimiento de las superficies a razón de unos 10m2 por persona de tal manera que en una vivienda pasaban a vivir familias diferentes (muchas veces de orígenes e intereses completamente distintos) y a compartir todos los espacios menos los dormitorios. Algo parecido a pisos compartidos donde los compañeros no se elegían, pero se tenían que aguantar indefinidamente. Las Komunalki convertidas eran la mayoría y algunas aun permanecen en el espacio ex-soviético.

[...]

Jelena Prokopljevic. Doctora Arquitecta.

Barcelona. Septiembre 2014

#Alberto Ruiz#Alexander Pasternak#Alexander Vesnin#arquitectura andaluza#arquitectura constructivista#arquitectura experimental#arquitectura japonesa#arquitectura moderna#arquitectura racionalista#arquitectura rusa#arquitectura social#arquitectura socialista#arquitectura soviética#Arturo Soria y Mata#Berthold Lubetkin#ciudad industrial#ciudad linear#ciudad socialista#constructivismo#constructivismo ruso#desarrollo urbano#Ebenezer Howard#espacio interior#historia#Ivan Ilich Leonidov#Jelena Prokopljević#Kazimir Malévich#Konstantín Stepánovich Mélnikov#Lazar Markovich Lissitzky#Le Corbusier

0 notes

Text

Overlooked Russian Bauhaus in limelight in Berlin

Russia's art and architecture school of the 1920s has long been overshadowed by its famous German counterpart, Bauhaus. A new exhibition in Berlin's Martin-Gropius-Bau brings overdue recognition.

In the 1920s, all of Europe was fascinated with Walter Gropius' art school, known as Bauhaus. Its revolutionary ambition to unify arts and craft to create high quality products and buildings made it the spearhead of a new avant-garde.

The Bauhaus style and vision were widely embraced, also in what was then the Soviet Union. Particularly in Moscow, many artists and intellectuals were eager to follow Walter Gropius' ideas.

Gropius had founded his Staatliches Bauhaus, or state Bauhaus school, in 1919 in Weimar. The following year saw the foundation of the Russian state art and technical school in Moscow, known as Higher Art and Technical Studios and abbreviated simply as Vkhutemas.

More than just Gropius

"While the Bauhaus school was revolving around its undisputed mastermind Gropius, the Vkhutemas had about a hundred figures like him," said Gereon Sievernich, director of the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin. The renowned exhibition hall, founded by a great uncle of Walter Gropius, has recently opened its new exhibition "VKhUTEMAS - A Russian Laboratory of Modernity."

Among the Vkhutemas' influential avant-gardists were celebrated architects like Alexey Shchusev, Nikolai Ladovsky, Konstantin Melnikov and painters like Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Wassily Kandinsky, who later taught Bauhaus classes at the Russian school.

Strong ties between Weimar and Moscow

Art historians and critics have often referred to the Vkhutemas as the Russian Bauhaus. And indeed, there is more that unites than separates the two avant-garde powerhouses of the 1920s. The Vkhutemas also aimed to unite arts and crafts and infuse artistic visions into the modern process of production.

The curricula and organizational structures of the two schools were almost identical. Both were divided into eight faculties: painting, sculpting, textiles, graphic reproduction, ceramics, metalwork, and woodwork. So it comes as no surprise that Gropius and the Vkhutemas established student exchanges in 1927 and 1928.

Very much in contrast to the competitive selection process in Weimar, there were no special prerequisites needed to study at the Vkhutemas. Consequently, the number of students at the Vkhutemas was much higher than at Staatliches Bauhaus - 2,000 compared to only 150 respectively.

Students outperforming professors

Students at the Vkhutemas were expected to learn artistic as well as mechanical skills. First, they studied abstract compositions and concepts, then they were assigned practical tasks like designing newsstands, water towers or communal housing.

The student designs at times exceeded those of their professors in vision and courage. For instance, after Ivan Leonidov presented his thesis before the school's examination board, the professors got up from their chairs to show their admiration for Leonidov's work and let him know that he had outdone his teachers.

Overdue recognition

Despite all the genius, the representatives of Vkhutemas never really found a unified artistic voice. The school's leadership, politics and personnel changed numerous times throughout its existence. In 1930, 10 years after it was founded, the Vkhutemas was closed as part of a Soviet education reform.

They were largely forgotten in the subsequent decades, their achievements outshined by the ubiquitous Weimar Bauhaus. Many art historians are convinced that this will change in the future and that the brilliance of the Vkhutemas crowd will finally be recognized.

~

Katja Kryzhanouskaya · 17.12.2014.

0 notes

Text

"The only living Russian architect well-known abroad is a former fantasist"

In the centenary of the Russian Revolution, Alexander Brodsky was the only national architect to offer a response. That says something about Russian architectural culture, suggests Owen Hatherley.

There was a building in London this autumn, by the last Russian architect to have any name recognition whatsoever outside that country. The architect in question is Alexander Brodsky, and the building was a pavilion called 101st km, Further Everywhere.

It was installed in Bloomsbury Square, just outside the long-established Russian cultural centre Pushkin House, who commissioned the project. It was a simple, spindly metal frame, clad in bolted-together felt. You had to clamber under the felt walls, which stopped a couple of feet before the bottom of the frame, to get in.

When you were inside, screens on each side of the walls displayed monochrome footage taken from the front of trains winding through the wastes of Siberia. On the walls, lit by little angled lamps, were printouts of poems by those who had been deported or exiled between 1917 and 1991 (with the exception of the pre-Soviet exile of Alexander Pushkin himself). In the centenary of the Russian Revolution, this was the only response by a major Russian architect. It was bleak, poetic, makeshift, and temporary.

The Soviet Union built a lot, but its architecture began and ended on paper

The Soviet Union built a lot – entire cities in Russia and Ukraine, practically entire countries in Central Asia – but its architecture began and ended on paper. Commemorative exhibitions, like the Design Museum's Imagine Moscow for instance, focused on the remarkable and unbuildable (then, for material reasons, now, for political ones) house-communes, Monuments to the Communist International and Palaces of Labour designed by the likes of Nikolai Ladovsky, Vladimir Tatlin and the Vesnin brothers in the aftermath of 1917.

But when the Soviet Union nosedived from reform to collapse in the second half of the 1980s, its best known designers abroad were the architect Alexander Brodsky – who had served his time working on standardised buildings in the state-run architectural firms – and the artist Ilya Utkin.

Their paper architecture, while equally based on a form of social fantasy, was the reverse in every way from what emerged from the revolution. It was deliberately irrational rather than coldly logical, antiquarian rather than futurist, darkly humorous rather than earnest, pessimistic and dystopian rather than optimistic and utopian, murky and gothic rather than crisp and glassy.

Related story

"Russian architecture is in a transitional state" says architect Yury Grigoryan

Brodsky and Utkin's paper work has just been republished, in the volume Cancelled 6/21/90, which features prints of plates made from zinc stolen from construction sites, which the pair made to be sold individually, and then crossed out. It's even more remarkable to look at these projects nearly three decades years on – they appear to be almost timeless.

The pair's interest in historical architecture could maybe be classed as postmodernist. The pileup of spires and domes across empty space in The Hill With a Hole shows a love of the picturesque and perverse qualities of 19th century eclecticism. The ironic and mournful Museum of Vanished Houses, which collects demolished historical buildings into an imposing, Aldo Rossi-like funereal grid, could be seen as a lament for the destruction of memory and an attack on the placelessness of modern architecture.

Brodsky commented that nothing good came out of the Russian revolution except constructivism

But Brodsky and Utkin didn't do polemic (too Soviet for them, perhaps). Their paper projects could be equally read simply as gorgeously crafted and fascinatingly illogical flights of fancy. Yet, when Brodsky came to making real, three-dimensional new space – as in the Cafe Atrium of 1989 – he first favoured an only partly parodic grotesque classicism that was ideal for the swaggering new rich, a style that has only just gone out of fashion as the house style of Moscow oligarchs. Accordingly, his usually temporary buildings of the last 10 years have tended towards rough, post-industrial and salvaged materials and oblique programmes, which is maybe closer to the gothic vision of the paper architecture.

In a public talk around the time the pavilion was opened, Brodsky commented that nothing good came out of the Russian revolution except constructivism. It's the sort of comment that helps explain why his generation of Russian liberals find themselves out of power. Those who once had free healthcare, full employment and near-free housing, and have experienced the last few decades as a plunge into terrifying poverty and uncertainty, couldn't be expected to agree with him. It also says something about capitalist Russian architectural culture that the only living architect well-known abroad is a former fantasist who only designs small pavilions.

Brodsky's anniversary pavilion seems predicated on the notion that deportation to Siberia began in 1917, when the horrible tragedy of the Russian revolution was people who had once been deported to Siberia under the Tsars meting out the same treatment to their enemies.

However, there's an uncanny power to Brodsky's response to this mostly vacuously remembered anniversary. In a grey London autumn, the wind blows the unpretentiously printed pages of Mandelstam, Shalamov, Tsvataeva et al, and the sound mingles with the rustling of the leaves. In dim November light, in the shadow of the pompously imperial Victoria House, you could almost be in Moscow, in a space that resembles either one of the gimcrack informal pavilions where people sell shawarma or socks, or a train carriage bound for somewhere appalling.

It's rare and important to make monuments to the victims of authoritarianism that are not themselves authoritarian

Inside, the texture of the building, with its untreated materials, showed an interest in surface and material rare in current architecture of any sort. It is put in the service of an unsentimental approach to history that sharply contrasts with the shrill official patriotism that has sharply increased in Russia in recent years.

In that, it's reminiscent of the public memorial project Last Address, where Brodsky has been the designer of a series of plaques placed onto the onetime homes of victims of Stalinist terror. There are many monuments to the victims of Stalinism, and often they're as pompous and nationalistic as the regime they're apparently opposing. Brodsky's plaques are matter of fact and hard, simple letters on a metal panel, with a hole in each where the photo on an ID card or passport might be. Brodsky's apparent belief that revolution only leads to terror is one that is encouraged by the current Russian government, but his memorial work belies that.

It's rare and important to make monuments to the victims of authoritarianism that are not themselves authoritarian.

Owen Hatherley is a critic and author, focusing on architecture, politics and culture. His books include Militant Modernism (2009), A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (2010), A New Kind of Bleak: Journeys Through Urban Britain (2012) and The Ministry of Nostalgia (2016).

The post "The only living Russian architect well-known abroad is a former fantasist" appeared first on Dezeen.

from ifttt-furniture https://www.dezeen.com/2017/11/29/owen-hatherley-opinion-alexander-brodsky-pushkin-house-pavilion-russian-architect-former-fantasist/

0 notes

Photo

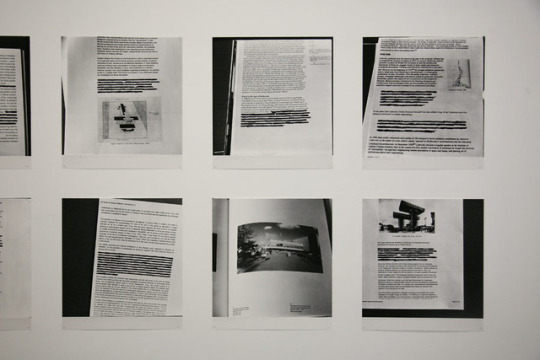

Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor

Deleting others' texts is not the smoothest way of entering a discourse; however, acts of removal/erasure/demolition are not without precedent in art history, let alone the history of social and political movements. By deleting essential parts of texts written by modernist architects such as Lina Bo Bardi, Le Corbusier, Roberto Burle Marx, Nikolai Ladovsky, Stefan Svetko, Ivan Matusik, Vladimír Dedecek and others, Mona Vatamanu and Florin Tudor point to the still common perception of modernism as a failed project. At the same time, their gesture is an affirmative one. Viewing the photographs of the fragmented writings, one feels the urge to imagine, construct something meaningful in place of the ruptures, and the question of "what?" puts the viewer in a liberated, albeit highly responsible position.

text by Judit Angel, Flying Utopia, tranzit.sk, 2015.

0 notes

Photo

Nikolai Ladovsky’s southern entrance to Krasnye Vorota metro... http://ift.tt/2rC7gVy

0 notes

Photo

Nikolai Ladovsky’s Lubyanka station on the Moscow metro, c1935 (via here)

#Nikolai Ladovsky#architecture#station#platform#public transport#Moscow#underground#metro#subway#1930s

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Design Museum's Imagine Moscow exhibition explores six unbuilt Soviet landmarks

Six radical designs for the Moscow skyline – proposed in the wake of the October Revolution, but never built – are showcased in an exhibition opening today at London's Design Museum.

The exhibition Imagine Moscow marks the centenary of the Russian Revolution by dusting off six shelved proposals for architecture in the newly formed Soviet Union, including what would have been the world's tallest skyscraper.

Dating from the 1920s and 1930s, the schemes show the impact of the union's socialist ideology on the work of architects like El Lissitzky and Konstantin Melnikov. Each of the schemes centres around Moscow's Red Square, the city's central plaza.

Drawings, models and projections of the six proposals are presented alongside constructivist and suprematist artworks and designs from the era.

"The October Revoluton and its cultural aftermath represent a heroic moment in architectural and design history," said exhibition curator Eszter Steierhoffer.

"The designs of this period still inspire the work of contemporary architects, and the radical ideas in the exhibition remain highly relevant to cities today.

"Imagine Moscow brings together an unexpected cast of 'phantoms' – architectural monuments of the vanished world of the Soviet Union that survive in spite of never being realised," she added.

Imagine Moscow is on show at theDesign Museum until 4 June 2017. Here's an overview of the six unbuilt projects it features, in roughly chronological order.

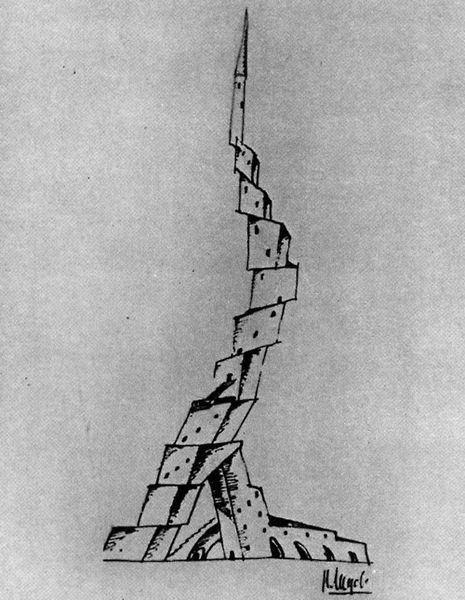

Communal House by Nikolay Ladovsky (1919-20)

Ladovsky's Communal House included shared facilities like nurseries and kitchens that aimed to lighten the workload for Soviet women – freeing them up to devote time to self improvement and to work.

The scheme was part of a wider attempt during the period to induce communal housing and amenities that would break down the traditional family unit.

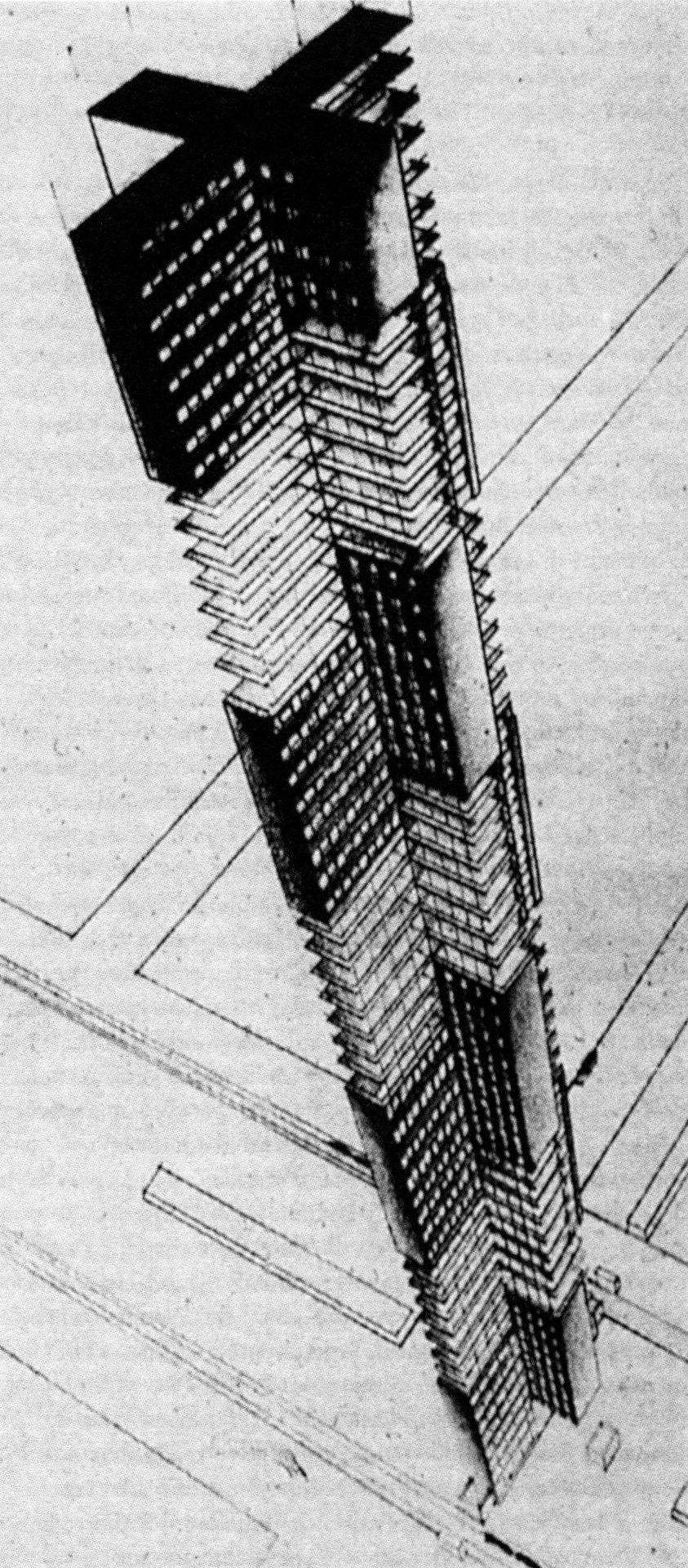

Cloud Iron by El Lissitzky (1923-25)

Lissitzky pitched his network of eight horizontal skyscrapers for Moscow's Boulevard Ring. The top heavy blocks – placed horizontally on top of vertical towers – aimed to maximise a relatively limited footprint.

The horizontal blocks were to contain offices and apartments, which would be linked with metro stations and tram stops at street level by the upright towers.

Lenin Institute by Ivan Leonidov (1927)

A huge sphere would have hosted an auditorium at Leonidov's Lenin Institute, with a slender tower to its rear containing 15 million books split across five reading rooms.

The complex would have also contained a planetarium and science lecture theatres, broadcasting events to the rest of the world by a radio station.

Health Factory by Nikolay Ladovsky (1928-29)

Ladovsky's second project in the exhibition is a design for a retreat on the Black Sea coast, intended to provide respite for weary city dwellers.

Individual rest pods were coupled with communal dining and activity spaces in the scheme, which aimed to improve the productivity of workers on their return to Moscow. Features included a dining hall where food was to be distributed by conveyor belt to do away with the street of queuing.

Commissariat of Heavy Industry proposals by the Vesnin brothers and Konstantin Melnikov (1934-36)

Planned for a vast 10-acre site opposite the Lenin Mausoleum on Red Square, the Commissariat of Heavy Industry could only have been built by demolishing a large chunk of Moscow's old town.

A winning design was never selected for the building, which was intended to celebrate the importance of industry to socialism, but the Design Museum showcases several proposals.

Melnikov's scheme was for a pair of 40-storey buildings linked by an escalator, while the Vesnin brothers suggested four blocks to mirror the towers of the Kremlin.

Palace of the Soviets by Boris Iofan (1931-41)

A 100-metre-tall statue of Lenin mounted on the roof of Iofan's Palace of Soviets would have taken thisbuilding to a height of 516 metres, making it the world's tallest at the time. The city's largest church – the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour – was demolished to make way for the proposal, which was allegedly selected by Josef Stalin himself.

Work began in the mid 1930s but was halted by the German invasion of 1941, and following the second world war Stalin's successor, Nikita Khrushchev, converted its foundations into an open-air swimming pool. A replica of the original cathedral now stands on the site.

Related story

Dead Space and Ruins exhibition questions the future of Soviet architecture

Exhibition photography is by Luke Hayes.

The post Design Museum's Imagine Moscow exhibition explores six unbuilt Soviet landmarks appeared first on Dezeen.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8217598 https://www.dezeen.com/2017/03/15/design-museum-imagine-moscow-exhibition-unbuilt-soviet-architecture-el-lissitzky-moscow-russia/

0 notes

Photo

Valentin Popov, Design for a Housing Commune in a New City, Nikolai Ladovsky Studio Vkhutein, 1928

#Valentin Popov#Architecture#Urbanism#Housing#Nikolai Ladovsky#Vkhutein#Design for a Housing Commune in a New City

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nikolai Ladovsky - Krasniye Vorota Metro Station, 1935

79 notes

·

View notes