#nanci dakesian

Photo

Sharon-A-Day, Day 477 (4/22/23)

Marvel Knights 14. On sale 8/22/01.

"Everything Dies"

Writer: Chuck Dixon

Penciller: Michael Lilly

Inker: Nelson Faro DeCastro

Letterer: Saida Temofonte

Colorist: Dan Kemp

Editor: Nanci Dakesian

Director (LMD) Sharon and Natasha meet!

#sharon carter#agent 13#natasha romanoff#black widow#marvel knights#chuck dixon#michael lilly#nelson faro decastro#saida temofonte#dan kemp#nanci dakesian

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharon-A-Day, Day 719 (12/20/23)

Marvel Knights 14. On sale 8/22/01.

"Everything Dies"

Writer: Chuck Dixon

Penciller: Michael Lilly

Inker: Nelson Faro DeCastro

Letterer: Saida Temofonte

Colorist: Dan Kemp

Editor: Nanci Dakesian

Sharon has a soul, but her LMD doesn't...

#sharon carter#agent 13#marvel knights#chuck dixon#michael lilly#nelson faro decastro#saida temofonte#dan kemp#nanci dakesian#black widow#dagger

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharon-A-Day, Day 611 (9/3/23)

Marvel Knights #15. On sale 10/10/2001.

"The Unreal World"

Writer: Chuck Dixon

Penciller: Eduardo Barreto

Inker: Nelson Faro DeCastro

Letterer: Jason Levine

Colorist: Dan Kemp

Editor: Nanci Dakesian

Natasha makes sure Director Sharon Carter is safe.

#sharon carter#agent 13#director carter#marvel knights#dagger#black widow#chuck dixon#eduardo barreto#nelson faro decastro#jason levine#dan kemp#nanci dakesian

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

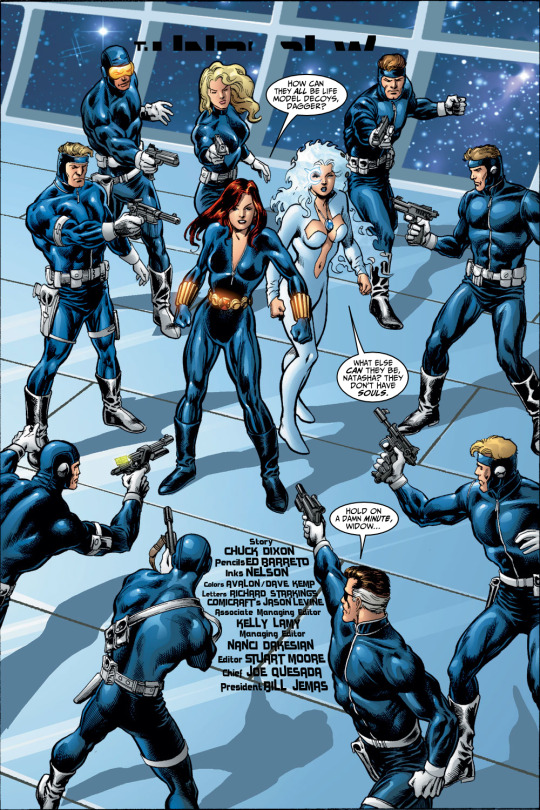

Sharon-A-Day, Day 167 (6/18/22)

Marvel Knights #15. On sale 10/10/01.

"The Unreal World"

Writer: Chuck Dixon

Penciller: Eduardo Barreto

Inker: Nelson Faro DeCastro

Letterer: Jason Levine

Colorist: Dan Kemp

Editor: Nanci Dakesian

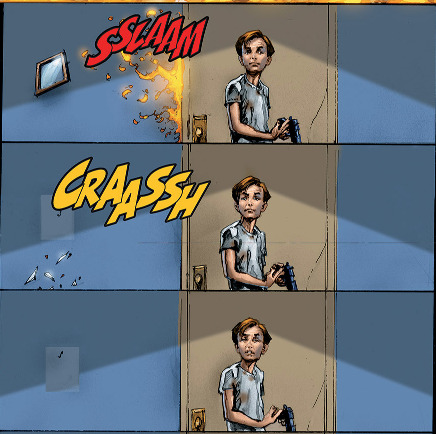

Sharon is replaced by an LMD.

#sharon carter#agent 13#marvel knights#black widow#dagger#chuck dixon#eduardo barreto#nelson faro decastro#jason levine#dan kemp#nanci dakesian

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sharon-A-Day, Day 323 (11/22/22)

Marvel Knights 14. On sale 8/22/01.

"Everything Dies"

Writer: Chuck Dixon

Penciller: Michael Lilly

Inker: Nelson Faro DeCastro

Letterer: Saida Temofonte

Colorist: Dan Kemp

Editor: Nanci Dakesian

Sharon has a soul, but her LMD doesn't...

#sharon carter#agent 13#marvel knights#dagger#natasha romanoff#black widow#chuck dixon#michael lilly#nelson faro decastro#saida temofonte#dan kemp#nancy dakesian

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

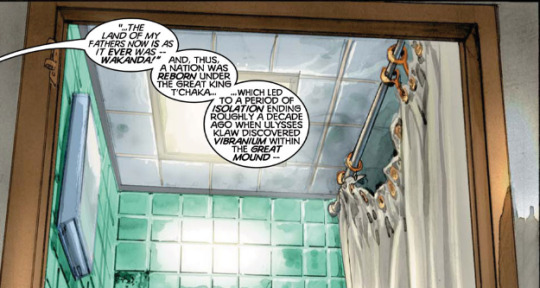

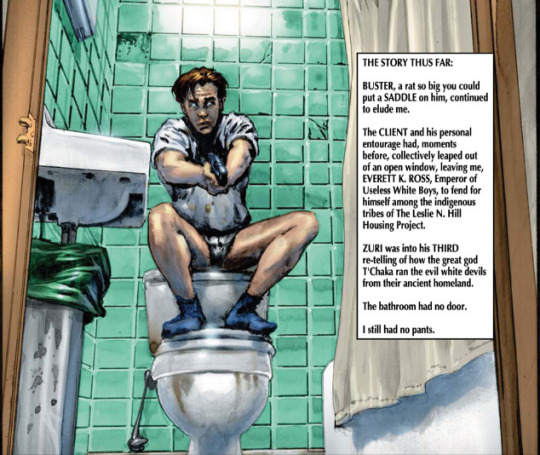

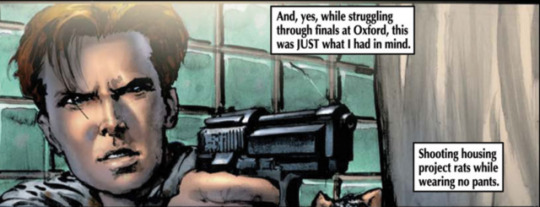

1-4: Fantastic Four #53 (August 1966). Stan Lee (Writer), Jack Kirby (Artist), Joe Sinnott (Inks), Artie Simek (Letterer)

5-10: Black Panther #1 (November 1998). Christopher Priest and Mark Texeira (Scribes), Joe Quesada (Storytelling), Alitha Martinez (Background Assists), Brian Haberlin (Colors), Nanci Dakesian (Managing Editor), Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti (Editors), Bob Harras (Editor-In-Chief).

Fantastic Four #53 is the second appearance of Black Panther and the first time we hear the character’s origin. There’s a lot to talk about in this story and its depictions of Wakanda and T’Challa, but given the focus of this research I wanted to call particular attention to the interruptions of The Thing and bring those scenes into conversation with our introduction to Everett K. Ross in the debut issue of the1998 Marvel Knights Black Panther book.

In the Fantastic Four issue, T’Challa has invited the superhero team (plus perpetual hanger-on Wyatt Wingfoot) to a “heroes’ ceremony” in his home country of Wakanda. During a break in the festivities, T’Challa tells his new friends the circumstances that led him to become a superhero and leader of Wakanda, beginning with a recollection of “T’Chaka, the Warrior King” (who is also T’Challa’s father).

Two pages in to the story of T’Chaka, The Thing lets out a huge yawn, interrupting the narrative to complain that it sounds like something out of “a million jungle movies.” Reed Richards scolds his teammate, but the Panther answers the charge that he is “boring” Ben Grimm by highlighting the wealth he and his country (though mostly he) possess thanks to their “virtually inexhaustible” supply of Vibranium, a precious metal. But as quickly as T’Challa resumes the story of his background, The Thing interrupts a second time, telling him that his “bedtime story” about “greedy ivory hunters” ruining Wakanda is old news to an avid consumer of Tarzan movies and Bomba novels. Reed again criticizes his teammate, though he doesn’t correct him. T’Challa claims that he does not mind the constant interruptions of his guest and admits the story may “sound contrived” even if it’s about Vibranium instead of ivory.

I thought this was a particularly weird set of exchanges until I started reading some of Christopher Priest’s remarks on the origins of his 1998 Black Panther project. Priest’s initial impressions of the character and his origins (recounted in a 2001 introduction to the first trade paperback collection of his run, text that was later posted to Priest’s personal web site) resonate in ways with Ben Grimm’s comments:

Panther was, by most any objective standard, dull. He had no powers. He had no witty speech pattern, bub. His supporting cast was a bunch of soul brothers in diapers with bones through their noses. King T'Challa is, by necessity, a man of secrecy and cunning, which is difficult to illustrate if he has thought balloons over his head telling the reader everything he's thinking. Or, worse, if he's narrating his own story and blathering on and on and on. Hard to convey cunning from a motormouth.

Like Grimm, Priest doesn’t have the patience to endure T’Challa’s “blathering.” Of course, there are differences in these readings of his dullness: the cliches cited by Priest and The Thing pull from different time periods and cultural perspectives, and Priest is more worried about the logistical challenges of scripting the thoughts and actions of the character in a compelling way.

Interestingly enough, one of the solutions Priest arrives at is modeled in a sense by this issue of Fantastic Four. A 2017 reader might quickly condemn Grimm’s interruptions both for their rudeness and their content: “You ain’t just whistlin’ Watusi, pal!” may be a remark that is “in character” for the gruff Thing, but it also reminds us of the whiteness of the book’s creative team (a more cringe-worthy moment materializes in the issue’s opening credits, where “The Ballet Forbush Terpsichorean Troupe” are acknowledged as the source of the issue’s “Native Dances”; there are other moments). But it also points to the use of Grimm as a stand-in for the book’s imagined audience and their presumed overexposure to the tropes invoked by the telling of T’Challa’s story. The letters pages of these books are interesting sites where we see Marvel more directly engaging with (and learning about) segments of their readership: though these are inevitably public extensions of the company’s promotional arm, at times we see there how the realities of the audience don’t always align with creators’ assumptions. But beyond these letters pages, we have characters like The Thing who serve the purpose of interrupting, commenting on, subverting, and mocking the action as it unfolds on the page.

Priest notes that the character of Everett K. Ross was introduced to his Black Panther book to provide a set of “Everyman’s eyes” to the Marvel Universe, a perspective that is more “social observer and deconstructionist” than loyal Marvel Zombie. Modeled on the sarcastic tenor of Chandler Bing from Friends, Ross is inserted into the Black Panther’s adventures as “the voice of the average Marvel reader, who no doubt wondered why Marvel was bothering with another Panther series.”

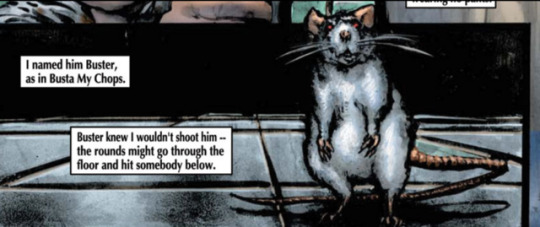

The opening pages of Black Panther #1 place Ross perfectly in this role. Priest and artist Mark Texiera focus our attention primarily on Ross as Zuri, one of T’Challa’s longtime aide and confidante, drones on off-panel about the Black Panther’s origins for the third time. Ross’ recollection in his caption and the snippet of the story we “hear” line up with some of the main beats from the story of T’Chaka Benjamin Grimm hears in Fantastic Four #53; however, Priest has shifted the perspective from that of Lee and Kirby to tell the story to the readers from The Thing’s bored and cynical perspective.

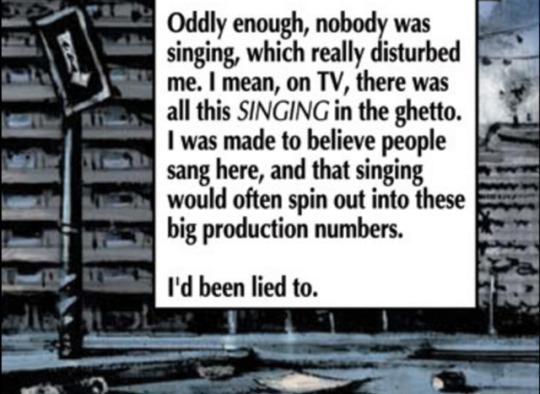

We also learn fairly quickly that Ross’ version of “the ghetto,” like The Thing’s images of Africa, are mostly drawn from pop culture. “I was made to believe people sang here,” he laments. Ross is both a classic unreliable narrator: he frequently interrupts himself and tells stories out of sequence, focusing more on seemingly-mundane details, like the fact that he is not wearing pants. His whiteness and his “Oxford” leanings are left showing: we see the lens he views T’Challa’s world through, warts and all.

While Priest notes that he is against the idea that Black Panther was reimagined as a “’black’ book” (for reasons involving the reception of these projects and perceived pigeonholing but also are derived from critiques of the perspectives offered by “a lot of black film and black comedians”), he also notes that going in to this work he “accepted the fact a great many readers would not be able to overcome the race thing, and withdrew Panther from the reader entirely.” “Panther's ethnicity is certainly a component of the series, but it is not the central theme. We neither ignore it nor build our stories around it.” Ross incessantly reveals the distance between himself and his “client” in ways that ask readers to situate themselves and their views in relation to the events unfolding on the page, Ross’ narration, and the glimpses we get of T’Challa. And as stories unfold, these perspectives align, diverge, and comment on one another. We also get Texeira’s commentary on his subjects as he interprets Priest’s script: I particularly love how Ross gets smaller, thinner, and more comically tiny as this particular issue unfolds and he gets deeper and deeper into this mess.

While the early issues of this run are set in Brooklyn, Priest’s run eventually takes his characters to Wakanda and elsewhere. In an FAQ about the book that responds to a question about why Black Panther “moves away from its more streetwise beginnings,” Priest notes that:

PANTHER was never intended to remain solely in the "hood." The premise allows for a much larger stage, and we've intended, from the beginning, to show a variety of situations and premises. Personally, I think limiting Panther to fighting thugs and hoods in New Lots perpetuated a much larger stereotype against him that's he's small-time or powerless. He's a king of a world power...

Black Panther offers us a particularly intriguing vision of New York City. The book is set in an odd space where the rest of the Marvel Universe is acknowledged (via guest stars and villains and references to continuity) but also kept a bit at bay, in part to enable Priest (via Ross) to poke at its conventions and limitations:

Again and again, I whined, there's no way Marvel would let me write this. It's a violation of the Fantasy Land Nice-Nice Accords, signed by both DC and Marvel, that says the US government is always good all the time, everyone accepts Panther, there is no racial divide in America, and the Avengers hold hands and sing and what have you. Mainstream comics were demented places where heroes actually referred to themselves as "heroes," and villains as "villains." These were places run by people who have run comic book companies far, far, far too long and have completely lost touch with popular culture or with what young people today are actually about. I have had my hand slapped more times than I can count for simply pointing out the absurdity of what we do- of these colorful men and women who fly around wearing their underwear on the outside of their clothes.

Ross’ narration likely signaled to some Marvel readers that this Black Panther book will play by different rules (though Priest notes that Marvel has had its rule-breakers in the past, most notably Steve Gerber). Similarly, the decision to set this initial storyline not just in New York City but in a particular section of Brooklyn (New Lots) is interesting. Priest and the creative team aren’t invested in realism -- he notes that Coming to America was an early influence in the idea for this new Black Panther book, and the book often has the feel of a 1990s buddy action film -- but they do nicely challenge and subvert the stories of the city we traditionally see in the Marvel Universe. They seem particularly interested in highlighting and exploring differences: the same story is often told more than once from several perspectives, or it is revised, exaggerated, or interrupted in some way. The stories are hyperlocal or detail-oriented in ways that other stories might not be, they feature characters with various relationships to these neighborhoods and experiences, and they are conscious of the ways other stories of the city (in pop culture and elsewhere) have impacted their perspectives.

#marvel comics#black panther#fantastic four#marvel knights#christopher priest#mark texeira#stan lee#jack kirby#1960s#1966#1990s#1998#nyc#brooklyn#new lots#east new york#everett k. ross#t'challa#wakanda#new york city#the thing#ben grimms#friends#chandler#comics

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Black Panther #1 (November 1998). Christopher Priest and Mark Texeira (Scribes), Joe Quesada (Storytelling), Alitha Martinez (Background Assists), Brian Haberlin (Colors), Nanci Dakesian (Managing Editor), Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti (Editors), Bob Harras (Editor-In-Chief).

I like that they used an actual Brooklyn police precinct and its correct address for this mugshot sequence. In fact, the precinct was the subject of a 2014 documentary (The Seven Five).

#marvel comics#brooklyn#new york#nyc#new lots#flatbush#east new york#black panther#christopher priest#mark texeira#1990s#1998#comics#nypd#mug shots#marvel knights

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Black Panther #1 (November 1998). Christopher Priest and Mark Texeira (Scribes), Joe Quesada (Storytelling), Alitha Martinez (Background Assists), Brian Haberlin (Colors), Nanci Dakesian (Managing Editor), Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti (Editors), Bob Harras (Editor-In-Chief)

#marvel comics#black panther#nyc#new york city#brooklyn#rooftops#christopher priest#mark texeira#1990s#1998#comics#marvel knights

0 notes