#more than half of my monthly income goes to rent and another big chunk to therapy

Text

between having hardly any spoons and being paranoid that i'm broke after nearly overdrawing my account a few weeks ago for the first time in years, i havent really been eating right (or enough) and ugh i'm just so tired of it. i've been living off of pb&js and whatever i can scrape together for dinner. im so tired

#im feeling really crappy today and it's ramping up The Sad#my eczema is flaring again bc the doc said to take a 1wk break from the steroid cream every 2wks#and god it hasnt been this bad in months#i'm hoping it's just bc i had some dairy last week so i'm gonna try to not have any this week and see if it clears up at all#and i'm trying really hard not to spend any money but i also havent cooked for myself in weeks#i know i'm just in a downswing and it's temprary but it doesnt make the thought of having a real sandwich make me want to cry any less#but this is what it's gonna be like when i finally get my act together and get my own car insurance#more than half of my monthly income goes to rent and another big chunk to therapy#at least my credit card is paid off but fuck i wouldnt be able to afford even pb&j if i still had that bill to pay#my job does not pay me nearly enough for how much work i do#i've been there almost 6mo now (damn) and it's starting to get a little stale#i've had a lot of jobs and this is the third longest i've ever stayed somewhere#second being the 8 or so months at the donut shop when i first moved here (which i only left bc pandemic)#and the longest being the 13mo of hell at the group home#i dont usually stay anywhere for more than a few months#but i'm finally getting some skills other than brewing coffee so i've gotta stick it out#and i do like my job. it's just... too much sometimes#idunno#im tired and sad and it still gets dark too early and i just havent been eating enough#i think i could use a nap but it's already 4 and idk i nap maybe once or twice a year and it's never worth it#personal

0 notes

Text

"How much house can I afford?"

How much house can I afford? Answering this question correctly is one of the keys to building a happy, wealthy life. Unfortunately, theres a vast housing industry in the U.S. thats geared toward providing the wrong answer.

You see, housing is by far the largest expense in most peoples budgets. According to the U.S. governments 2016 Consumer Expenditure Survey, the average American family spends $1573.83 on housing and related expenses every month. Thats more than they spend on food, clothing, healthcare, and entertainment put together!

Too many folks struggling to make ends meet focus their attention on fine-tuning their budget. They try to save big bucks by clipping coupons, growing their own food, and/or making their own clothes. While theres nothing wrong with frugal habits I applaud everyday thriftiness! all of these actions combined wont (and cant) have the same impact on your budget as keeping your housing payments affordable.

Part of the problem is what I call the Real-Estate Industrial Complex, each piece of which has a vested interest in convincing consumers that bigger, more expensive homes are better. Real-estate agents, mortgage brokers, home-shopping shows, and glossy magazines all encourage folks to buy at the top end of their budget. But buying at the top end of your housing budget is dangerous.

Buying a home is a huge decision, financially and otherwise. If youre going to purchase a place, its important to know how much house you can truly afford.

Debt-to-Income Ratio

Economists have used decades of financial stats to create computer models to predict how much people can afford to spend on housing and debt. Banks use these models to figure out how much they think you can afford to spend on housing.

Traditionally, lenders use whats called a debt-to-income ratio (or DTI ratio) a measure of how much of your income goes toward debt every month to estimate how much you can afford to pay for a home without risk of defaulting. This might sound complicated, but its not.

To find this ratio, divide your monthly debt payments by your gross (pre-tax) income. So, for example, if you pay $400 toward debt every month and you have an income of $4000, then your DTI ratio is 10%. If you pay $800 toward debt on a $4000 income, your DTI ratio is 20%. The lower your debt-to-income ratio, the better.

Banks and mortgage brokers look at two numbers when deciding how much to loan:

The front-end DTI ratio (sometimes called the housing expense ratio), which includes only your housing expenses: mortgage principle, interest, taxes, and insurance.The back-end DTI ratio (also known as the total expense ratio), which include all of the above plus other debt payments like auto loans, student loans, and credit cards.

The key thing to understand about debt-to-income ratios is that theyre used to estimate the lenders risk, not yours. That is, your mortgage company uses them to check whether they think youll be able to make the payments not whether you can comfortably make the payments.

If you want room in your budget for fun, you should opt for a lower debt-to-income ratio than your real-estate agent and mortgage broker say you can use.

If youre a money nerd, you can read more about debt-to-income ratios at Fannie Maes website.

How Much House Can You Afford?

During the 1970s (before credit-card debt was common), DTI wasnt split between front-end and back-end. There was only one ratio, and it was 25%. If your mortgage, taxes, and insurance costs were less than 25% of your income, people assumed you could make the payment.

This is still an excellent rule of thumb: Spend no more than 25% of your budget on housing. (In fact, this is the number that money guru Dave Ramsey advocates.)

That said, debt-to-income guidelines have relaxed over the years.

When my ex-wife and I bought our first home in 1993, our mortgage broker told us that our front-end DTI ratio had to be 28% or lower, meaning we couldnt pay any more than 28% of our gross income toward housing. The back-end DTI ratio was capped at 36%, which meant that our housing expenses and other debt payments combined couldnt be more than 36% of our income.When my ex-wife and I bought a new home in 2004, the accepted DTI ratios had grown by 5%. That 28% figure is outdated, we were told. Most people can go as high as 33%. The back-end ratio had been raised to 38%.According to the Fannie Mae website, in 2018 maximum back-end DTI ratios are up to 45% (and sometimes even 50%). These numbers are insane. Nobody should be spending half of their gross income on debt not even mortgage debt! Thats a recipe for financial disaster.

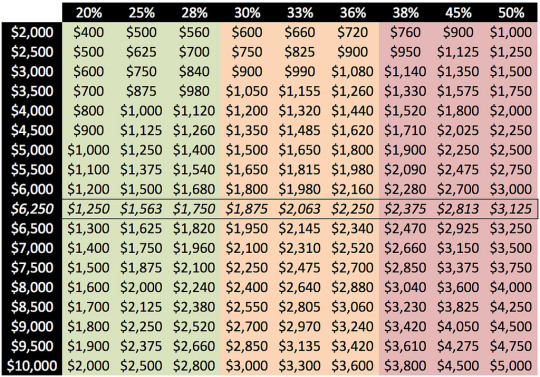

Heres a little table I whipped up to show what sort of housing payment youd be looking at based on your pre-tax income (the left-hand column) and various debt-to-income ratios (the header row):

A 5% increase in your debt-to-income ratio might not seem like a big deal. But when youre talking about a house payment, its huge.

In 2016, the average American household earned $74,664 before taxes. Using this, a 5% change would be $3733.20 per year or $311.10 per month. Many folks lost their homes during the housing crisis because they took on mortgage payments that were just $300 more than they could afford each month.

Real-Life Examples

When my ex-wife and I moved in 2004, our housing payments went from around $1200 per month to roughly $1600 per month. This $400 per month difference was enough to make me panicked about money.

Similarly, my youngest brother made the mistake of believing the banks when they told him he could afford a big housing payment. He could at first. But when the financial crisis hit in 2008 and 2009, he was screwed. Because hed bought at the top end of his budget, when his income faltered, so did his ability to pay his mortgage. He lost his home to foreclosure.

For the most part, banks are happy to lend you as much money as you want. (Within reason, of course, and if your credit is good.) Theyre not going to stop you from taking on more debt if their computer models say you can afford it. Its up to you to exercise caution.

In The Automatic Millionaire Homeowner, David Bach writes [emphasis is mine]:

You should generally assume that the amount the bank or mortgage company will loan you is more than you should borrowDont fool around with this. Do the math. Be realistic about your situation. Dont pretend youre in better shape than you are.

Remember: Nobody cares more about your money than you do. Your real-estate agent, mortgage broker, and bank all have a vested interest in encouraging you to buy as much house as possible their incomes depend on it. Listen to what they have to say, but make your decision based on whats best for you.

Playing House

If you think youre ready to buy a house, take a few months to do a trial run. In The Money Book for the Young, Fabulous, and Broke, Suze Orman says that you should play house before you buy a house. I like this idea. Heres how it works:

Figure out how much you think you can afford to pay for a home every month, including mortgage and maintenance. Lets use $1750 as an example.Subtract the amount youre currently paying for housing. If your rent (or current mortgage) is $1000 per month, youd subtract this from our hypothetical $1750 to get $750 per month.Open a new, separate savings account. On the first day of each of the next six months, stick $750 into this account.

This exercise lets you experience what its like to make a higher housing payment. If you cant make these numbers work, Orman says you need to wait:

If you miss one payment, or if you are consistently late in making the payments, you are not ready to buy a home. If you can handle the extra payments, then youve got the thumbs-up to start looking for a home to buy.

Generally speaking, once youve saved 20% for a down payment and you can afford monthly mortgage payments, youre ready to start looking for a home. Yes, you can buy a home with a smaller down payment I bought my first place with a 2% down payment! but itll cost you in the long run. Youll need to carry private mortgage insurance (PMI), youll pay more in interest, and you could put yourself in a position where you cant afford to keep your home.

The Bottom Line

Homebuyers are often told to buy as much house as you can afford. But the problem with this advice is that it leaves you without a buffer. What if you lose your job? What if youre forced to sell your home after housing prices have dropped?

Instead of buying as much house as you can afford, buy only as much house as you need. Think of conventional debt-to-income ratios as ceilings, not targets.

Give yourself margin for error. Instead of basing your home-buying budget on a 36% front-end DTI ratio, consider dropping that to 28%. Or, better yet, 25% (just like the olden days!).

If you have an average U.S. household income of around $75,000, a 36% DTI ratio would lead you to budget $2250 per month for housing (assuming you have no other debt). If you were to go with a more conservative 25% DTI ratio, that budget would be $1563 per month. Thats a savings of $687 per month over $8000 per year! Just think: What could you do with a chunk of change like that?

Another way to create a buffer is to base your budget on your net (take-home) pay instead of your gross pay. Or, if youre in a relationship where both partners work, run the numbers for only one of the two incomes.

No, you wont be able to afford a big mortgage if you do what Im recommending. But you know what? You wont feel pinched by your mortgage payments. And youll be at much less risk the next time the housing market implodes. Best of all, you can plow all of the money youve saved on housing into a building a ginormous wealth snowball!

https://www.getrichslowly.org/how-much-house/

0 notes

Text

“How much house can I afford?”

“How much house can I afford?” Answering this question correctly is one of the keys to building a happy, wealthy life. Unfortunately, there’s a vast housing industry in the U.S. that’s geared toward providing the wrong answer.

You see, housing is by far the largest expense in most people’s budgets. According to the U.S. government’s 2016 Consumer Expenditure Survey, the average American family spends $1573.83 on housing and related expenses every month. That’s more than they spend on food, clothing, healthcare, and entertainment put together!

Too many folks struggling to make ends meet focus their attention on fine-tuning their budget. They try to save big bucks by clipping coupons, growing their own food, and/or making their own clothes. While there’s nothing wrong with frugal habits — I applaud everyday thriftiness! — all of these actions combined won’t (and can’t) have the same impact on your budget as keeping your housing payments affordable.

Part of the problem is what I call the Real-Estate Industrial Complex, each piece of which has a vested interest in convincing consumers that bigger, more expensive homes are better. Real-estate agents, mortgage brokers, home-shopping shows, and glossy magazines all encourage folks to buy at the top end of their budget. But buying at the top end of your housing budget is dangerous.

Buying a home is a huge decision, financially and otherwise. If you’re going to purchase a place, it’s important to know how much house you can truly afford.

Debt-to-Income Ratio

Economists have used decades of financial stats to create computer models to predict how much people can afford to spend on housing and debt. Banks use these models to figure out how much they think you can afford to spend on housing.

Traditionally, lenders use what’s called a debt-to-income ratio (or DTI ratio) — a measure of how much of your income goes toward debt every month — to estimate how much you can afford to pay for a home without risk of defaulting. This might sound complicated, but it’s not.

To find this ratio, divide your monthly debt payments by your gross (pre-tax) income. So, for example, if you pay $400 toward debt every month and you have an income of $4000, then your DTI ratio is 10%. If you pay $800 toward debt on a $4000 income, your DTI ratio is 20%. The lower your debt-to-income ratio, the better.

Banks and mortgage brokers look at two numbers when deciding how much to loan:

The front-end DTI ratio (sometimes called the housing expense ratio), which includes only your housing expenses: mortgage principle, interest, taxes, and insurance.

The back-end DTI ratio (also known as the total expense ratio), which include all of the above plus other debt payments like auto loans, student loans, and credit cards.

The key thing to understand about debt-to-income ratios is that they’re used to estimate the lender’s risk, not yours. That is, your mortgage company uses them to check whether they think you’ll be able to make the payments — not whether you can comfortably make the payments.

If you want room in your budget for fun, you should opt for a lower debt-to-income ratio than your real-estate agent and mortgage broker say you can use.

If you’re a money nerd, you can read more about debt-to-income ratios at Fannie Mae’s website.

How Much House Can You Afford?

During the 1970s (before credit-card debt was common), DTI wasn’t split between front-end and back-end. There was only one ratio, and it was 25%. If your mortgage, taxes, and insurance costs were less than 25% of your income, people assumed you could make the payment.

This is still an excellent rule of thumb: Spend no more than 25% of your budget on housing. (In fact, this is the number that money guru Dave Ramsey advocates.)

That said, debt-to-income guidelines have relaxed over the years.

When my ex-wife and I bought our first home in 1993, our mortgage broker told us that our front-end DTI ratio had to be 28% or lower, meaning we couldn’t pay any more than 28% of our gross income toward housing. The back-end DTI ratio was capped at 36%, which meant that our housing expenses and other debt payments combined couldn’t be more than 36% of our income.

When my ex-wife and I bought a new home in 2004, the accepted DTI ratios had grown by 5%. “That 28% figure is outdated,” we were told. “Most people can go as high as 33%.” The back-end ratio had been raised to 38%.

According to the Fannie Mae website, in 2018 maximum back-end DTI ratios are up to 45% (and sometimes even 50%). These numbers are insane. Nobody should be spending half of their gross income on debt — not even mortgage debt! That’s a recipe for financial disaster.

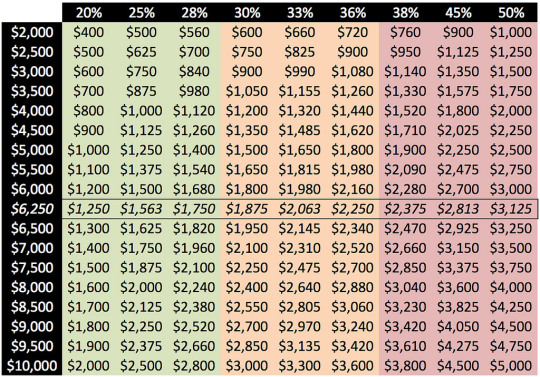

Here’s a little table I whipped up to show what sort of housing payment you’d be looking at based on your pre-tax income (the left-hand column) and various debt-to-income ratios (the header row):

A 5% increase in your debt-to-income ratio might not seem like a big deal. But when you’re talking about a house payment, it’s huge.

In 2016, the average American household earned $74,664 before taxes. Using this, a 5% change would be $3733.20 per year or $311.10 per month. Many folks lost their homes during the housing crisis because they took on mortgage payments that were just $300 more than they could afford each month.

Real-Life Examples

When my ex-wife and I moved in 2004, our housing payments went from around $1200 per month to roughly $1600 per month. This $400 per month difference was enough to make me panicked about money.

Similarly, my youngest brother made the mistake of believing the banks when they told him he could afford a big housing payment. He could at first. But when the financial crisis hit in 2008 and 2009, he was screwed. Because he’d bought at the top end of his budget, when his income faltered, so did his ability to pay his mortgage. He lost his home to foreclosure.

For the most part, banks are happy to lend you as much money as you want. (Within reason, of course, and if your credit is good.) They’re not going to stop you from taking on more debt if their computer models say you can afford it. It’s up to you to exercise caution.

In The Automatic Millionaire Homeowner, David Bach writes [emphasis is mine]:

You should generally assume that the amount the bank or mortgage company will loan you is more than you should borrow…Don’t fool around with this. Do the math. Be realistic about your situation. Don’t pretend you’re in better shape than you are.

Remember: Nobody cares more about your money than you do. Your real-estate agent, mortgage broker, and bank all have a vested interest in encouraging you to buy as much house as possible — their incomes depend on it. Listen to what they have to say, but make your decision based on what’s best for you.

Playing House

If you think you’re ready to buy a house, take a few months to do a trial run. In The Money Book for the Young, Fabulous, and Broke, Suze Orman says that you should “play house before you buy a house”. I like this idea. Here’s how it works:

Figure out how much you think you can afford to pay for a home every month, including mortgage and maintenance. Let’s use $1750 as an example.

Subtract the amount you’re currently paying for housing. If your rent (or current mortgage) is $1000 per month, you’d subtract this from our hypothetical $1750 to get $750 per month.

Open a new, separate savings account. On the first day of each of the next six months, stick $750 into this account.

This exercise lets you experience what it’s like to make a higher housing payment. If you can’t make these numbers work, Orman says you need to wait:

If you miss one payment, or if you are consistently late in making the payments, you are not ready to buy a home. If you can handle the extra payments, then you’ve got the thumbs-up to start looking for a home to buy.

Generally speaking, once you’ve saved 20% for a down payment and you can afford monthly mortgage payments, you’re ready to start looking for a home. Yes, you can buy a home with a smaller down payment — I bought my first place with a 2% down payment! — but it’ll cost you in the long run. You’ll need to carry private mortgage insurance (PMI), you’ll pay more in interest, and you could put yourself in a position where you can’t afford to keep your home.

The Bottom Line

Homebuyers are often told to “buy as much house as you can afford”. But the problem with this advice is that it leaves you without a buffer. What if you lose your job? What if you’re forced to sell your home after housing prices have dropped?

Instead of buying as much house as you can afford, buy only as much house as you need. Think of conventional debt-to-income ratios as ceilings, not targets.

Give yourself margin for error. Instead of basing your home-buying budget on a 36% front-end DTI ratio, consider dropping that to 28%. Or, better yet, 25% (just like the olden days!).

If you have an average U.S. household income of around $75,000, a 36% DTI ratio would lead you to budget $2250 per month for housing (assuming you have no other debt). If you were to go with a more conservative 25% DTI ratio, that budget would be $1563 per month. That’s a savings of $687 per month — over $8000 per year! Just think: What could you do with a chunk of change like that?

Another way to create a buffer is to base your budget on your net (take-home) pay instead of your gross pay. Or, if you’re in a relationship where both partners work, run the numbers for only one of the two incomes.

No, you won’t be able to afford a big mortgage if you do what I’m recommending. But you know what? You won’t feel pinched by your mortgage payments. And you’ll be at much less risk the next time the housing market implodes. Best of all, you can plow all of the money you’ve saved on housing into a building a ginormous wealth snowball!

The post “How much house can I afford?” appeared first on Get Rich Slowly.

from Finance https://www.getrichslowly.org/how-much-house/

via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Link

Written by R. Ann Parris on The Prepper Journal.

I happen to cruise the same prepper forum as this child’s father . He’s all the time popping up with updates of what he’s ordered in or purchased on the “What Did You Prep Today” thread – parts for his expanding power system, tons of first-aid supplies, another hunting blind, potassium iodide and more gas masks, more MOPP suits, replacing his fifth wheel with a pop-up camper, endless survival books.

//

He’s not really doing anything hundreds if not thousands aren’t. He’s worried about a game-changing Z-event – doesn’t matter what it is. His wife somewhat supports him, and ignores chunks of the rest. When the power goes out, he flips some switches and keeps them going. When his son first got sick, he identified some gaps in their preps – namely, ways to control nausea and ways to combat low oxygen in patients.

Then the real world kicked the door in, and so did the “uh oh”.

The amount that was not covered by their insurance was a sucker punch, on top of lost wages and normal bills, and the additional expenditures for traveling and staying with an in-hospital patient.

That kind of thing happens. All the time.

It’s the kind of thing in between our normal, everyday life and an actual major disaster that just doesn’t get prepared for all that often.

The World We Live In

We live in a highly unpredictable world. You’d think, as “preppers”, we’d accept that, and prepare for it.

We commonly don’t though.

We prepare for the worst case and a short-term storm or a flat tire, and with frightening regularity, we skip the vast number of things that can happen in between. In some or many cases, we live paycheck to paycheck or via debt to get our supplies for that worst and that storm, without actually being able to readily and more easily weather life’s mid-range crises.

Most of us don’t have to practice much actual triage in our daily lives. Man, am I grateful not to be in those fields, or living in a world that does require it. At some point in the future, we may have to make those hard calls, or watch people fade away from us, helpless to do anything at all because resources just don’t exist.

Right now, though, it’s unlikely that we’re going to watch our children, spouses, or parents slowly fade away in bed without getting them every medical advantage we can beg, steal and borrow against, and then waiting for the bills to roll in. So we need to get ready for them.

Our “bunker” (really, it’s food and hygiene supplies), our generator and fuel supplies, and our cached medical supplies may help us defray our living expenses while we shovel out of a financial hole, whatever the cause of that hole. For those starting out and with less than three, six or twelve months of really well-rounded supplies, however, it may be a minuscule fraction of the $8K the prepper above is trying to raise.

In other cases, such as vehicle or roof repairs, we may need that money now and find ourselves maxing out cards or taking out a loan – in some cases, a personal loan with a higher interest rate than a vehicle loan – which then leaves us even more vulnerable.

The Things That Go Wrong

Predicting just how much a common, no-frills surgery or dental procedure is going to end up costing out of pocket is a little bit like throwing darts blindfolded, even with major insurance coverage. It’s one of the many flaws in our healthcare system, and it can lead to some painful surprises, just as it did for the family above with their unexpected and uncommon situation.

There are minor disasters like a leak that means an out-of-this-world water bill, discovering that bees now inhabit 85% of an outer wall, and vet bills.

There are somewhat less-minor disasters such as cut hours or other loss of wages, or injury or circumstances that limit how much we can hunt or garden or forage and thus require making that up out of pocket.

Seasonal trends in the greater financial world can mean our income and costs can vary greatly. Some types of self-employment come in ebbs and flows that are hard to predict. Workers comp and unemployment are fractions of what regular wages are in some cases.

Can you take the hit on water, repair, and field losses from a broken irrigation line?

Then there are the disasters like farm-ag insurance that doesn’t actually cover our loss of stock to a dog or illness, or weather conditions leading to feed and hay prices going through the roof.

There are heart-breakers like loss of spouse – either divorce or death or debilitating injury that leave a big gap between former wages and real-work “income” and their social security disability.

All kinds of things go wrong, all the time.

Armageddon-ELE and a snowstorm are only the extreme ends of the spectrum. There’s a lot of middle ground we need to cover if we want to call ourselves prepared.

We need a plan for things in between a night spent in the cold because our kayak went downriver without us, and our plan to batten down the hatches of the bunker, board our ark, or shoulder our bag and go eat bugs and roots in the forest.

So what do we do about it? Especially those just starting out, or who have hit that ugly hump where they thought they were prepared, then discovered the world of sustainability and self-reliance that entails even more purchases and education?

We do have options. We have one more hurdle to leap first, though.

Stuff is the same as cash

Most preppers agree Ammo would be highly valuable in a SHTF Event.

I hate to see the belief that firearms and ammo, and our hardware like generators, are going to bail us out.

I’ve seen the theory that firearms hold value well. Depending on how you define value, maybe. Depending on how long you can wait, they also might hold more value. Run a test, though.

There are books, just like for vehicles, that define value of firearms based on a percent of their condition. That’s the top dollar somebody’s going to pay, unless you can find a sympathy buy, nostalgia buy, or somebody willing to pay for specialty etching.

Most of the time, if you need cash relatively quickly, you’re not going to get that top dollar, even if you did accurately gauge whether your shotgun, revolver, and rifle are at 75% or at 85%. You’re going to a gun store or a pawn store.

In some cases, they’ll take a percentage of the price you want and stick it on a shelf to see if it sells, but you won’t get paid until it does. If you have other money forthcoming, there’s the pawn option – which lets you buy it back for basically what they gave you upfront, but with a time limit.

Most of the time, you’re going to take a hard hit on that best-case value. See, that’s the most they’re going to be able to get. So off the top, they’re going to cut the price by the overhead – the costs of running and manning a storefront and-or internet presence.

There are definitely guns out there that are investments. Man, how many of us wish we’d snagged a few more of those K98’s, 91/30’s, or those .22LR German training pistols while they were under $100, now that they’re sitting at $200+?

Those are the exception.

Your bog standard 870-500, AR, and Glock, even purchased used, is not going to return the same money it was purchased for. In some cases, it’s not going to return 2/3 and may only hit half what it cost.

The same for ammo, unless you’re in the middle of a shortage. Especially if you’re looking to offload fast, chances are good you’re going to get less than 75% what you paid.

Sometimes hardware like chainsaws and generators, reloading presses, and tow-behind attachments will fetch decent returns back, but if you purchased new and are selling used, or if you need to sell fast, you may be in for a nasty surprise there, too. Same goes for selling off some of those canning, long-storage food, and equine supplies.

Please, don’t take my word for it, or anybody else’s.

Pretend you’re there, with a sick kid and $8K you can’t cover, out of space on credit cards and unable to wait 7-14 days for a loan. Haul some of the examples in to a shop. Call around.

Better to find out now than later.

Fire insurance may or may not cover outbuildings like barns and sheds, and their contents to include livestock, let alone feeding & getting livestock out of the cold afterward.

Getting Right

A lot of the middle-ground disasters revolve around finances, either losing our income or having to shell out. It’s not fun and in many cases, income is one of the fixed facts of our lives. There are a few things we can do to help build resilience, though.

Insurance: Go over your policies – all of them. Flood coverage is almost always separate. Wildfire and house-fire coverage can vary wildly. Don’t play the odds on health coverage for big disasters and cancer treatments; plan for that disaster, too. Make sure you check on things like preexisting conditions, such as diabetes or world travel that may make you an exception to coverage.

The biggest is to make sure insurance actually covers your losses.

Make sure life insurance and disability coverage actually covers your mortgage, or rent for enough time for your family to get up on its feet. Make sure vehicle coverage and theft coverage actually pays for the gear inside the vehicle, too.

In some/many cases, firearms are severely limited in coverage without additional or separate policies, and so are precious metals.

We can increase our deductibles to lower our monthly bills, but to do so, we need to make sure we actually have the deductibles on hand to pay out – all of them, in case a tree falls across all the vehicles and a roof, and then there’s a house fire while we’re staying in a hotel/campground.

That’s where honest self-assessment comes into play. If we’re not going to keep that payout on hand, we need to stick to the lower deductibles and just pay the higher monthly rates.

Have an emergency credit card with zero balance.

Emergency Credit Card: Have a card with nothing on it, enough to cover those insurance deductibles above and for that hotel room and the unexpected expenses that crop up. Cash is great, and I endorse keeping plenty on hand, but insurance doesn’t cover or severely limits paper money replacement and it’s bulky. If it can get tucked somewhere accessible in the middle of the night that won’t be affected by the “it” crisis facing the family, go for it, but keep a card handy, too.

Companies like to send cards to even people with bad credit and no jobs. If you’re not actually using it until a disaster occurs, the obnoxious interest rate doesn’t matter. But again, that’s about individual willpower.

Stop Spending: That can be harder than it sounds for some people. “It’s only” and “it’s on sale” and the eye-catchers at stores can wind up adding a fair bit to totals. Lack of organization and counts means I’ve seen people with six or seven of the same thing that doesn’t actually wear out all that often or 47 cheap flashlights, which is money that could have been spent far differently or tucked in a jar for a rainy day.

If impulse purchases are a problem write on the inside of your dominant hand “do I need this – how much of an hourly wage equivalent is this?”. Framing things into that last question has actually helped others, really and truly. Is that $8 fast-food combo or gadget really worth an hour or a half-hour of your daily income?

To combat internet impulse buys, take the card information off your accounts after every purchase, and make it a habit to keep cards in another room from computers. Stick the same question on those cards or on a slip in the wallet.

Cut Expenses: Every situation is different. Chances are good though, that most of us have something we can cut.

Whether it’s $90/year for Amazon Prime for our TV and movies, $8/month for Hulu, and whatever internet costs versus a cable package, gong to VoIP instead of a landline (you can plug in a phone to dial 911 even without phone service), or really deciding if we need those smart phones – or the major carrier contracts instead of reloadables, electronics are a main source.

Tally up what we spend and where, every penny; from the candy added to carts to the brand clothes and shoes, those $1 coffees instead of a thermos and lunches/snacks out instead of packing them. Consider what we cook, and what we could save by cooking differently.

Where we shop, and how much we spend on a DIY project (to include cooking) versus waiting or just buying something, are big contributors to what we spend.

We may also seriously consider downsizing if we rent, assessing the vehicle we drive for its maintenance and fuel costs versus something more economical, or getting out of a house that’s a money suck.

Communicate Goals: When it comes to the expenses and to the spending mentioned above, we’re going to have to talk to our families in many cases, and that’s going to be a headache, because what we prioritize is different.

You have to leave in at least some of the sanity savers, and it’s going to have to be transparently balanced, especially if you’re the only or the primary prepper. Cutting data, internet, subscriptions, and TV while you still buy a tacticool hatchet-prybar-tent stake and 500 rounds of ammo is likely to go down like ground glass.

In fact, forget the word “prepper” and all the world of gear and goodies while you’re working the financials. Every bank, credit union and investment agency is going to have mail-outs they’re happy to send you about budgeting and financial security. Get them. Print the example prepper’s story. Sit down with the goal to simply get out of a rut or become more financially stable.

Stay calm, stay open, be understanding, be non-aggressive, and walk in with some ideas but also asking about their solutions, too, and willing to compromise.

Write out the anticipated costs – roofs, tires, replacement appliances, vet bills, medical and dental bills, vehicles, graduation and college, annual shopping binges (holidays, back-to-school, vacations/trips, garden supplies). Come up with a “now” plan, and 1-2, 5, and 10-year plans and goals.

Involve everybody, and remember that their priorities are as prized to them as yours are to you, and what’s “obvious” is not going to be so for everyone else.

Piggy Bank vs. Zero-Balance: There’s going to always be a balancing act between paying off debt and sticking money in a kitty for another time. It’s another one that’s going to be deeply personal and individual. Have some money available, instead of immediately dumping every penny against a debt. Build up or keep enough on hand to go ahead and pay deductibles and for the credit cards that get so many people in trouble.

Just as we slowly build up food storage a few days, then a week, then a month, then 3 months, build financial backups that prevent late fees or huge interest rates.

Once we have it, pick the things that cost us the most (highest interest) and-or that we can eliminate pretty quickly, and focus on those.

House floods – It does not take Katrina or Sandy to rack up tens of thousands of dollars in un-covered damages.

Preparing for the Middle Ground

Our food storage and some of our other prepping supplies absolutely helps with some of those disasters, lessening our expenditures, but it can take some time for the savings to equal what we really need to pay out, and sometimes we need to pay that now. Too, if our supplies are things we will not actually use while the rest of the world is chugging around like normal (beans and rice 5-7x a week, scrubbing board, NBC or surgical suite) they’re not going to help us dig out of a hole.

The only thing less-sexy and less-interesting than getting right financially is going to be making up those disks and binders of our important information. Do it anyway. Make a chart or a graduated pie graph that can be colored in, weekly or monthly, so that we have a nice, physical tangible and can look at something to see what we’ve accomplished. It’ll help keep us on track.

Getting on track and staying on track financially is probably harder than any other aspect of preparedness. Try. There’s a lot that goes wrong in our world that does not involve ARs, survival gardens, INCH-BO bags, and making our own charcoal.

The post Are You Really Prepared for the Real World? appeared first on The Prepper Journal.

from The Prepper Journal

Don't forget to visit the store and pick up some gear at The COR Outfitters. How prepared are you for emergencies?

#SurvivalFirestarter #SurvivalBugOutBackpack #PrepperSurvivalPack #SHTFGear #SHTFBag

0 notes

Text

"How much house can I afford?"

How much house can I afford? Answering this question correctly is one of the keys to building a happy, wealthy life. Unfortunately, theres a vast housing industry in the U.S. thats geared toward providing the wrong answer.

You see, housing is by far the largest expense in most peoples budgets. According to the U.S. governments 2016 Consumer Expenditure Survey, the average American family spends $1573.83 on housing and related expenses every month. Thats more than they spend on food, clothing, healthcare, and entertainment put together!

Too many folks struggling to make ends meet focus their attention on fine-tuning their budget. They try to save big bucks by clipping coupons, growing their own food, and/or making their own clothes. While theres nothing wrong with frugal habits I applaud everyday thriftiness! all of these actions combined wont (and cant) have the same impact on your budget as keeping your housing payments affordable.

Part of the problem is what I call the Real-Estate Industrial Complex, each piece of which has a vested interest in convincing consumers that bigger, more expensive homes are better. Real-estate agents, mortgage brokers, home-shopping shows, and glossy magazines all encourage folks to buy at the top end of their budget. But buying at the top end of your housing budget is dangerous.

Buying a home is a huge decision, financially and otherwise. If youre going to purchase a place, its important to know how much house you can truly afford.

Debt-to-Income Ratio

Economists have used decades of financial stats to create computer models to predict how much people can afford to spend on housing and debt. Banks use these models to figure out how much they think you can afford to spend on housing.

Traditionally, lenders use whats called a debt-to-income ratio (or DTI ratio) a measure of how much of your income goes toward debt every month to estimate how much you can afford to pay for a home without risk of defaulting. This might sound complicated, but its not.

To find this ratio, divide your monthly debt payments by your gross (pre-tax) income. So, for example, if you pay $400 toward debt every month and you have an income of $4000, then your DTI ratio is 10%. If you pay $800 toward debt on a $4000 income, your DTI ratio is 20%. The lower your debt-to-income ratio, the better.

Banks and mortgage brokers look at two numbers when deciding how much to loan:

The front-end DTI ratio (sometimes called the housing expense ratio), which includes only your housing expenses: mortgage principle, interest, taxes, and insurance.The back-end DTI ratio (also known as the total expense ratio), which include all of the above plus other debt payments like auto loans, student loans, and credit cards.

The key thing to understand about debt-to-income ratios is that theyre used to estimate the lenders risk, not yours. That is, your mortgage company uses them to check whether they think youll be able to make the payments not whether you can comfortably make the payments.

If you want room in your budget for fun, you should opt for a lower debt-to-income ratio than your real-estate agent and mortgage broker say you can use.

If youre a money nerd, you can read more about debt-to-income ratios at Fannie Maes website.

How Much House Can You Afford?

During the 1970s (before credit-card debt was common), DTI wasnt split between front-end and back-end. There was only one ratio, and it was 25%. If your mortgage, taxes, and insurance costs were less than 25% of your income, people assumed you could make the payment.

This is still an excellent rule of thumb: Spend no more than 25% of your budget on housing. (In fact, this is the number that money guru Dave Ramsey advocates.)

That said, debt-to-income guidelines have relaxed over the years.

When my ex-wife and I bought our first home in 1993, our mortgage broker told us that our front-end DTI ratio had to be 28% or lower, meaning we couldnt pay any more than 28% of our gross income toward housing. The back-end DTI ratio was capped at 36%, which meant that our housing expenses and other debt payments combined couldnt be more than 36% of our income.When my ex-wife and I bought a new home in 2004, the accepted DTI ratios had grown by 5%. That 28% figure is outdated, we were told. Most people can go as high as 33%. The back-end ratio had been raised to 38%.According to the Fannie Mae website, in 2018 maximum back-end DTI ratios are up to 45% (and sometimes even 50%). These numbers are insane. Nobody should be spending half of their gross income on debt not even mortgage debt! Thats a recipe for financial disaster.

Heres a little table I whipped up to show what sort of housing payment youd be looking at based on your pre-tax income (the left-hand column) and various debt-to-income ratios (the header row):

A 5% increase in your debt-to-income ratio might not seem like a big deal. But when youre talking about a house payment, its huge.

In 2016, the average American household earned $74,664 before taxes. Using this, a 5% change would be $3733.20 per year or $311.10 per month. Many folks lost their homes during the housing crisis because they took on mortgage payments that were just $300 more than they could afford each month.

Real-Life Examples

When my ex-wife and I moved in 2004, our housing payments went from around $1200 per month to roughly $1600 per month. This $400 per month difference was enough to make me panicked about money.

Similarly, my youngest brother made the mistake of believing the banks when they told him he could afford a big housing payment. He could at first. But when the financial crisis hit in 2008 and 2009, he was screwed. Because hed bought at the top end of his budget, when his income faltered, so did his ability to pay his mortgage. He lost his home to foreclosure.

For the most part, banks are happy to lend you as much money as you want. (Within reason, of course, and if your credit is good.) Theyre not going to stop you from taking on more debt if their computer models say you can afford it. Its up to you to exercise caution.

In The Automatic Millionaire Homeowner, David Bach writes [emphasis is mine]:

You should generally assume that the amount the bank or mortgage company will loan you is more than you should borrowDont fool around with this. Do the math. Be realistic about your situation. Dont pretend youre in better shape than you are.

Remember: Nobody cares more about your money than you do. Your real-estate agent, mortgage broker, and bank all have a vested interest in encouraging you to buy as much house as possible their incomes depend on it. Listen to what they have to say, but make your decision based on whats best for you.

Playing House

If you think youre ready to buy a house, take a few months to do a trial run. In The Money Book for the Young, Fabulous, and Broke, Suze Orman says that you should play house before you buy a house. I like this idea. Heres how it works:

Figure out how much you think you can afford to pay for a home every month, including mortgage and maintenance. Lets use $1750 as an example.Subtract the amount youre currently paying for housing. If your rent (or current mortgage) is $1000 per month, youd subtract this from our hypothetical $1750 to get $750 per month.Open a new, separate savings account. On the first day of each of the next six months, stick $750 into this account.

This exercise lets you experience what its like to make a higher housing payment. If you cant make these numbers work, Orman says you need to wait:

If you miss one payment, or if you are consistently late in making the payments, you are not ready to buy a home. If you can handle the extra payments, then youve got the thumbs-up to start looking for a home to buy.

Generally speaking, once youve saved 20% for a down payment and you can afford monthly mortgage payments, youre ready to start looking for a home. Yes, you can buy a home with a smaller down payment I bought my first place with a 2% down payment! but itll cost you in the long run. Youll need to carry private mortgage insurance (PMI), youll pay more in interest, and you could put yourself in a position where you cant afford to keep your home.

The Bottom Line

Homebuyers are often told to buy as much house as you can afford. But the problem with this advice is that it leaves you without a buffer. What if you lose your job? What if youre forced to sell your home after housing prices have dropped?

Instead of buying as much house as you can afford, buy only as much house as you need. Think of conventional debt-to-income ratios as ceilings, not targets.

Give yourself margin for error. Instead of basing your home-buying budget on a 36% front-end DTI ratio, consider dropping that to 28%. Or, better yet, 25% (just like the olden days!).

If you have an average U.S. household income of around $75,000, a 36% DTI ratio would lead you to budget $2250 per month for housing (assuming you have no other debt). If you were to go with a more conservative 25% DTI ratio, that budget would be $1563 per month. Thats a savings of $687 per month over $8000 per year! Just think: What could you do with a chunk of change like that?

Another way to create a buffer is to base your budget on your net (take-home) pay instead of your gross pay. Or, if youre in a relationship where both partners work, run the numbers for only one of the two incomes.

No, you wont be able to afford a big mortgage if you do what Im recommending. But you know what? You wont feel pinched by your mortgage payments. And youll be at much less risk the next time the housing market implodes. Best of all, you can plow all of the money youve saved on housing into a building a ginormous wealth snowball!

https://www.getrichslowly.org/how-much-house/

0 notes