#mmr

Text

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

my favourite part of my room in moshi monsters rewritten!

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republicans are soft on disease control. We all remember the MAGA anti-vaccine hysteria when the COVID-19 vaccines became available.

They are now turning their attention to the polio vaccine which was approved for use in the US on 12 April 1955. The number of polio cases in the US dropped from 57,879 in 1952 to 910 in 1962 and became rare by the early 1970s.

Thanks to anti-vaxxing conspiracy crackpots, polio returned to the US for the first time in three decades in 2022.

New Hampshire Republicans want to weaken vaccination requirements to kowtow to anti-science elements in their state.

New Hampshire could soon beat Florida—known for its anti-vaccine Surgeon General—when it comes to loosening vaccine requirements. A first-in-the-nation bill that’s already passed New Hampshire’s state House, sponsored only by Republican legislators, would end the requirement for parents enrolling kids in childcare to provide documentation of polio and measles vaccination. New Hampshire would be the only state in the US to have such a law, although many states allow religious exemptions to vaccine requirements.

Currently, Republicans control New Hampshire’s state House, Senate and governor’s office—but that isn’t a guarantee that the bill will be signed into law, with GOP Gov. Chris Sununu seemingly flip-flopping when it comes to disease control. Sununu did sign a bill in 2021 allowing people to use public places and services even if they did not receive the Covid-19 vaccine. But the next year, the governor vetoed a bill that would bar schools from implementing mask mandates.

The polio vaccine, first offered in 1955, and the MMR shot, which treats the highly infectious measles, mumps, and rubella viruses, are two very crucial vaccines both in the US and internationally. Since the year 2000 alone, vaccines against measles are estimated to have saved over 55 million lives around the world.

[ ... ]

Vaccine hesitancy is rising among parents of young children. A 2023 survey from the Pew Research Center found that around half of parents with kids four or younger thought that not all standard childhood vaccines—a list that also includes hepatitis B, rotavirus, DTaP and chickenpox—may be necessary. Anti-vaccine misinformation plays a role in this phenomenon, which began before the Covid-19 pandemic, but has certainly increased since. In a 2019 UK report, about 50 percent of parents of young kids encountered false information about vaccines on social media.

Gov. Chris Sununu is a spineless putz. In some ways he's like Lindsey Graham who likes to send smoke signals of independent thinking but always comes crawling home to Daddy Donald.

Sununu campaigned for Nikki Haley and blamed Trump for January 6th. But that hasn't stopped him from endorsing Trump anyway. Instigating a coup d'état does not disqualify somebody from the presidency in Sununu's opinion.

GOP's Chris Sununu tries, fails to defend his Trump endorsement

Sununu may do for polio in New Hampshire what Trump did for COVID in the entire US in 2020.

#new hampshire#polio#polio vaccine#poliomyelitis#anti-vaxxers#vaccine hesitancy#chris sununu#flip-flopper#republicans#contagious diseases#vaccine disinformation#public health#vaccination requirements#pandemics#measles#mmr#covid-19#donald trump#election 2024#vote blue no matter who

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julia Métraux at Mother Jones:

New Hampshire could soon beat Florida—known for its anti-vaccine Surgeon General—when it comes to loosening vaccine requirements. A first-in-the-nation bill that’s already passed New Hampshire’s state House, sponsored only by Republican legislators, would end the requirement for parents enrolling kids in childcare to provide documentation of polio and measles vaccination. New Hampshire would be the only state in the US to have such a law, although many states allow religious exemptions to vaccine requirements.

Currently, Republicans control New Hampshire’s state House, Senate and governor’s office—but that isn’t a guarantee that the bill will be signed into law, with GOP Gov. Chris Sununu seemingly flip-flopping when it comes to disease control. Sununu did sign a bill in 2021 allowing people to use public places and services even if they did not receive the Covid-19 vaccine. But the next year, the governor vetoed a bill that would bar schools from implementing mask mandates.

The polio vaccine, first offered in 1955, and the MMR shot, which treats the highly infectious measles, mumps, and rubella viruses, are two very crucial vaccines both in the US and internationally. Since the year 2000 alone, vaccines against measles are estimated to have saved over 55 million lives around the world.

The CDC recommends that kids get their first dose of MMR vaccine between 12 and 15 months of age, and a first dose of the polio vaccine at around two months old. All states currently require children to have at least started vaccination against measles and polio in order to enroll in childcare, according to the nonprofit Immunize.org. A CDC report found that for the 2021-2022 school year, around 93 percent of children had received the MMR and polio vaccines by the time they entered kindergarten. That figure drops to less than 80 percent for both vaccines—the lowest rate in the country—in Alaska, where a measles outbreak could be devastating.

Rises in anti-vaccine sentiments have largely been linked to concerns that vaccines cause health issues, like the debunked claim that the MMR vaccine leads to kids being autistic. What parents may want to keep in mind is that polio and measles themselves are disabling conditions: according to the World Health Organization, 1 in 200 polio infections leads to irreversible paralysis. Children who get measles can experience symptoms including swelling of the brain. Death is always a possibility, too.

[...]

The bill would strike language requiring that immunization records be submitted to childcare agencies, but would keep those requirements for students enrolling in kindergarten through 12th grade. As of 2022, according to the nonprofit ChildCare Aware of America, there are some 700 licensed childcare centers and homes in New Hampshire (which doesn’t require the Covid-19 vaccine for enrollment in childcare, either, despite its efficiency in reducing both death rates and acute symptoms).

New Hampshire could be the first state to repeal polio and measles vaccination requirements for children with HB1213. This is a consequence of the GOP's pandering to anti-vaxxer extremist neanderthals in recent years. #NHLeg

#Anti Vaxxers#Anti Vaxxer Extremism#New Hampshire#Vaccine Mandates#Schools#Coronavirus#Polio#Measles#Polio Vaccines#Measles Vaccines#Vaccines#MMR#New Hampshire HB1213

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

So call me when you need me! I can be your #1! 🎤🎤🎤

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

draws....pretty girls....endlessly......2nd girl is @unknownangels oc matilda <3

#my art#nw#mmr#i am simply trying to practice self love by posting my art instead of just#showing it in group chats and ignoring it

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you haven't had measles, a single measles vaccine, or MMR (or you've had them but something happened to your immune system since), talk to your GP.

I got my MMR a few years back when it looked like mumps was making a comeback and I promise it hurts less than an ear piercing, doing one single push-up, or the twinges of middle-age.

It says London but measles remains airborne for hours and trains and planes exist. It is vaccine-preventable and confined to humans. It should be eradicated by now, not on the verge of a comeback.

#MMR#Measles#Andrew Wakefield is a dangerous fraud#Andrew Wakefield needs a smack in the gob#Public health

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

poor broke ugly

wc: 2946

au: band au

ch: lark, matilda, benji

Lark doesn’t usually drink.

He’s not opposed to one or two beers, especially when they’re free (Lark Tanaka has never, in his life passed up something free), but he also doesn’t drink really. Not with the intention to get drunk and never because it tastes good—because it doesn’t, and people are lying when they say it does. Alcohol makes his throat burn, sours his stomach, turns his face unpleasantly warm. It darkens his cheeks pink, which he’s always found unflattering a look and neither bar or club lighting does much for his complexion to begin with.

That’s why they’re outside.

That’s the excuse anyway. Outside, for the cool night air and not outside, because then it’s just them. Lark had suggested it (“Do you want to come outside with me?”), when they’d both gotten that free second or third or maybe fourth drink from the bartender. She was a fan, liked their underground grass roots style, had a tattoo of a lyric that Benji had written when he was only eighteen years old—and Lark for what’s it’s worth, had tried so hard to pay attention. He was good with fans, he cared about fans, not the way some lead singers did because it bolstered their ego or put them on a pedestal.

The band didn’t exist without the fans. But…even when she was talking, when she was mixing Matilda’s cocktail and she was asking Lark about something (what was the bartenders name? She had said it to him when he’d leaned over to shake her hand), all he could do was stare at Matilda. She didn’t look bad under the wavering neon lights. He didn’t think she could look bad.

They’d dipped out the exit door behind the bar seconds later into cool night air that instantly made Lark feel just a smidge more sober. It was a sweet hole in the wall sort of place, the kind of venue that Benji really loved. There’s a twinge of guilt that Lark isn’t inside with Benji—they don’t have to stick hip to hip and usually don’t. That was always the best part of Benji and Lark; that they could be Benji and Lark, not something squished together. They could have their own moments of peace completely unconnected to the other, no matter how much starting a band together had solidified they were together forever now.

Maybe he just feels guilty, because it was so obvious how badly he wanted to be alone with Matilda. Maybe he feels guilty because he’s still unsure of their new guitar player or he feels guilty because he’d not done his best this show, because he was tired and hungry and his phone had twelve missed phone calls.

Matilda and Lark fall into an easy, if not safe, conversation. Did you like the opener, your mic was too loud, I almost tripped, Benji broke another stick tonight, someone asked me to sign their hand—it isn’t the sort of stuff he wants to be talking about. It’s just the sort of conversation that happens between…coworkers, he supposes. The thought makes the entire night feel duller.

She’s sipping her cocktail, the straw between her fingers, when they pause in front of a dark antique store on the strip. It’s well past midnight. The sign is flipped to close.

“That says poor broke ugly,” Lark says, pointing to a shoddy made zen garden with a wooden stick sign, something obviously not vintage at all. Matilda laughs so suddenly and so hard that she spits a bit of the cocktail (Goddess of the Underground had been the name, and its an ugly sort of purple color that smells too much like vodka). She’s wiping at the little spill on her chin with her thumb when she leans closer to look at it. Lark has to struggle not to pay attention to the spill of her hair over her shoulder. He keeps one hand in his pocket, the other holding the glass of beer he shouldn’t have been allowed to leave with.

“My sister was always better with Japanese,” he comments.

“How come?”

“No idea,” Lark laughs. “I dunno—maybe she just gets languages better. Japanese is hard enough even people living in Japan can fucking suck at it.”

“American’s aren’t that great at English, either, if you haven’t noticed.” She takes another sip of her drink. Something hangs in the air between them. A moment that is either going to pass, or going to be taken. Matilda fiddles with the straw in her drink, casts him a sideways glance as they stand in front of the fake antique shop.

Then,

“My brother too. Like the language thing, but not by being bilingual. He was just always better in every dinner conversation—or networking thing we had to go to. Always knew what to say, or when to laugh.”

“Not at a funeral.”

“What?” Matilda laughs then, steps closer, lets her shoulder hit the glass window. He knows he’s drunk because the outline of her is fuzzy and soft, ethereal and distant. If he lifted a hand and touched her shoulder, they’d just disappear right into each other. Lark tilts his head back, smiling up at the night sky. There’s too much light pollution in this shitty city to see the stars, but that’s okay. He closes his eyes briefly, sighing.

“I laughed during my grandfathers funeral and almost got kicked out.”

Matilda lifts a hand. Her fingers take the zipper of his jacket. She toys with it.

“What was so funny?” She asks, head tilted. The sound of the zipper is agonizingly loud. The wind touches the hollow of his throat as it’s exposed. The hint of her tongue behind her teeth every time she speaks is purple, just like the drink.

“Nothing,” Lark replies truthfully.

—

“Oh my God, fourteen?” Her laugh has gotten louder the longer they walk. She’d drained the rest of her cocktail and placed the glass on a low brick wall to forget about—and then they’d shared his beer together. Taking sips, passing it back and forth. Now, they’re drunk. No longer in the middle of sobriety and tipsy. They are both drunk, walking back toward the bar, as the night ends somewhere between pleasant and surreal. Lark is smiling at her, hands deep in his pockets so he isn’t too tempted to take one of hers.

“I don’t have a good excuse.” Lark shakes a palm through his messy hair, trying not to continue smiling. He shouldn’t be grinning ear to ear, talking about his juvenile record like this. Only, that was the game they were playing. Trading little vulnerable secrets, because the night felt immortal like that. Deeply intimate and only for them. “It wasn’t even a nice car. It was a Honda.”

“You have shit taste.”

“It was unlocked.”

“That’s like—that is so much less impressive, then? I’m not impressed anymore.”

“You were impressed to begin with?”

He watches her roll her eyes. Some of her eyeshadow has started to rub away. Mascara sticks in little dots underneath her eyes as well. He wishes the bar was further away.

“It’s your turn,” he reminds her. He dares to nudge Matilda with his elbow, glancing up at her once more. Every time he does, he’s distracted once more by a strand of hair that continues getting caught in her lip gloss by the occasional gust of wind. She’d once applied it, standing beside him in a shitty bar bathroom. He was trying to not poke his eye out with an eyeliner pen and she was laughing—and then taking it from him and making him lean against the sink counter and doing it for him. She’d imitated the popped mouth look that girls always wore when applying make up to their eyes.

Fuck, he’s drunk. He wants to kiss her.

Then remembers the notorious disaster of his ex boyfriend being their guitarist for their first EP.

Matilda swings around to stand in front of him, pausing them on the sidewalk. She drapes her wrists over his shoulders—not really touching him but, not not touching him either.

“I was a cheerleader in high school,” she confesses. It makes Lark laugh immediately, head tilting back. One of his hands leaves his pocket, without thinking. It closes in around her hip. She’s wearing a satin textured top that drapes all over her upper body. Her skirt is tight though, the material stretching around her more square shape. He likes the look of her, the silhouette she creates when the lights are on her in the dark, on the stage.

“That’s adorable.”

“Wow, adorable?” She sneers, her lip curling. “That’s not how most men react to cheerleaders.”

“Ew.” Lark says it without meaning to. Then he blinks, feeling stupid and caught off guard. “Sorry—I just mean, if any guy hears that and is immediately thinking anything other than ‘wow that’s so cute’, he’s probably a fucking weirdo.” Matilda is silent in her observation of him. Her wrists are still sitting on his shoulders, their chests closer than they’ve ever been. Lark hasn’t moved his hand from her hip.

“How come Benji never calls you Elias?”

“Oh.”

“Oh?” She presses a bit closer. One of her hands has suddenly moved to the back of his head. Her long keyboardist fingers capture a few strands of his hair. The idle movement, the soft playful tug makes something dark and hungry unfurl in his lower stomach. He blinks more than a few times again, looking down at her exposed collarbone.

“I hadn’t started my transition when I met Benji. I mean, I had, but—I hadn’t figured out a name yet. I went by Lark on the website we posted our samples to. It was a nickname Xavier had given me.” Not for the first time, he wishes Xavier was more than just a part of stories he’d occasionally tell to everyone. He wishes Xavier was there—had even a shred of musical talent so he could be part of a band, instead of part of the U.S. military industrial complex he’d accidentally sold his soul to at seventeen. Matilda would like Xavier. He feels sure of that.

“Anyway—Daisuke is hard to pronounce. No one gets it right on their first try.”

“Daisuke,” Matilda says confidently.

“I just said it.”

“Doesn’t seem that hard to pronounce.”

“Okay, but I just said it—I meant every teacher I’ve ever had has pronounced it wrong reading it off an attendance sheet.” She’s grinning, a little mischievous, a little mean. Her eyes are two bright sparks in the dark. He realizes she’s teasing him. And he realizes how much he likes it. It only makes that hungry arousal in his stomach worse. Lark snorts and squeezes her hip, a bit harder than maybe he would have if he was entirely sober. She shifts a bit closer.

“When I finally picked another name, I had just been going by Lark for so long. I dunno, it doesn’t bother me. Half the time Benji is calling me dickhead and I’m telling him to shut up.” They both laugh then, which makes the heat in Lark feel less like a devouring need to press her against a wall and more like—more comforting. Fireplace warmth. He can feel himself sobering up. Something about Matilda liking Benji so much made Lark like her even more than his obvious attraction.

“Can I call you Elias?” she finally asks, chin tilted down so their eye contact is direct and severe. Maybe he isn’t that sober. Her words feel like a wax drip over his sensitive skin. He licks his lips—something in her expression suddenly looks a lot less practiced. She’s staring at his mouth now. He almost wishes it was cold enough to see their breaths mingle in the air. He wants to know how close he is to her, in a measurable distance like that.

“Yeah,” he finally concludes and then promises to hate himself for it later. Because then Matilda is grinning again, pushing their chests together in one quick shove. And then she’s gone. Dancing forward on the sidewalk toward the parking lot of the bar. The crowd has mostly thinned to nothing.

“I was lying, by the way!” She calls, head tilted over her shoulder. The streetlights make her look like something painted in watercolor. “Like, I’d ever be a cheerleader.”

“You lied?” Lark huffs. “Now I have to guess what else you lied about! I told you I stole a car!” Her laughing begins to mix with the sounds of cars starting in the bar parking lot, people still lingering and talking, not the kind that would want their attention, and he’s thankful for it.

He rushes after her, but still doesn’t take her hand.

—

Lark opens the back of the beat up white van that carries most of their shit and crawls inside. It smells like cigarette smoke, sweat and burnt plastic. Somehow it’s one of the most comforting things in the world, considering Lark doesn’t smoke and hates being close enough to people he can smell them and the burnt plastic means something probably got unplugged wrong when they broke down their set. Someone will get yelled at for it later, but in that moment he doesn’t care about anything.

Instead, he finds a curled up body on a blanket covering amps. Benji sleeps with his knees tucked up, one hand pressed underneath a cheek and the other arm somehow holding his legs closer. He looks angelic like that, in the dark, shoulders rising and falling calmly. Lark shouldn’t wake him up—Benji doesn’t ever sleep enough.

But Lark is already crawling over top of him without thinking. He thought he was sober before, but the second Matilda parted (at the entrance to the bar, still smiling that slightly mean-sweet grin, telling him she’s not sleeping in a car, thanks for the offer) he felt drunk all over again. The alcohol he doesn’t usually drink swims in his blood stream and clouds all thoughts—her lips had been stained dark by whatever had been in her drink.

“Ge’off me,” Benji snaps, suddenly awake. His rough hands curl around Lark’s shoulders, fingers dug in. Suddenly not angelic looking, but snarling mad and ready to fight for his personal space back. It only takes a second for Lark to blink, both bleary and innocently, for Benji to melt back. “Fuckin’ hell, don’t just do that. Alright?”

Instead of answering right away, Lark continues his path up Benji. He slides his way between the wall of the van and the drummers solid back. Benji has the lingering faint scent of a cigarette after all—means he’s not as good about quitting as he keeps claiming he is. It’s such a wildly familiar scent that Lark doesn’t mind it at all. He wraps arms around Benji’s stomach, pulls them in close.

They used to have to sleep like this a lot on the road. After a gig, they’d take the night in the van because hotels were expensive. And sometimes when they weren’t expensive, they’d just walk out to their van having been broken into anyway. A guitar stolen, or something vandalized. It was almost safer to keep themselves tucked into the back like this, but Lark also thought a part of it was indulgent. It felt realer this way. Like they were a real pair of musicians, trying their best.

Benji is still grumbling under his breath, but he adjusts to get himself comfortable again.

“Are you tired?” Lark asks.

“I was just fuckin’ sleepin’, yeah?”

“No, I mean—are you tired of trying to do this? Make this a thing?”

It was better, now. They were going places, now. Matilda had connections that were taking them farther—they were getting in touch with agents, with potential record deals, with bigger venues, better vans, maybe a tour bus. Maybe hotels that could be comped here and there. Lark resists the urge to squeeze Benji, just to remember he’s real and has been there since it was—

Since it was skipping food afterward because they needed to afford gas. Or eating ramen five nights in a row until they were both sick, but at least it was food. Since his ex boyfriend almost ruined it, since Reno almost ruined it, since Lark almost ruined it once before because his parents wouldn’t stop trying to get him to come home (and that was all he’d wanted since he was sixteen, but he knew that come home meant, help us with Akari).

I just want t’play drums, mate.

I just want to sing, man. Lie, because when he looks at Matilda, he wants more and…

“You’re ticklin’ my hair every time you talk,” Benji replies instead.

Lark leans around a shoulder and blows air against Benji’s ear, which makes him bark out a sound. He rolls onto his side, taking Lark and shaking him until they fall onto the floor of the van, in a terrible wrestling match that has them both laughing like rabid hyenas.

The shaking van and their loudly rough and playful sounds do not dispel the rumor that Lark and Benji are sleeping together, which is a rumor that has thrived since the conception of the band. And yet, the next day comes and Lark takes the first leg of the drive and Benji tells him;

“Just ask her on a date, already. Like, after this stint. Just go to a fuckin’ movie or somethin’.”

“She likes horror movies,” Lark replies, because she’d told him, just the night before.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

sillies :]

based on these

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

rot

wc: 6.8k

He thinks that maybe Dunwall is a place built on grief. One quick glance into the pages of its history is marred with plague, with suffering, with tragedy and loss and horror and subjugation and hate. It must be built upon the bones of something ancient and angry; or worse, exhausted.

Maran teases when he insists all of this one evening, when they’ve broken into his father’s liquor cabinet and sit together, alcohol-leaden and curved backs slumped together. Maran leans over more, draping himself over Benji’s shoulder. His prickly scalp scrapes against his cheek, and it’s about as comforting and familiar a texture as he’s ever known.

Perhaps the last swig had been one too many, though.

“The whales,” Maran repeats, a sullen and soulful impression of Benji, his deeper tone. “Mar, the whales.” He giggles high and mad, hiccups at the end. “Whale revenge.”

Benji scowls, although Maran can’t see it, and plants his feet to push back against his best friend’s weight. He’s liquid in his limbs, though, and accomplishes little more than toppling them both in a laughing heap to the ground. The upending of the world makes his head spin, and when his doubled vision shimmies back into something he can parse, something whole and relatively steady, they’re shoulder-to-shoulder and gazing up at the sky.

The garden is cool and quiet this time of year, buds opening to blossoms with every slow-creep day of warmth. Soon, everything will burst forth. Soon, the color and smell of new life.

Despite that, beyond the yard and far walls, the bustle and toil and stench of the city remains. For all potential of goodness, the beauty and loveliness that might happen within the confines of the city, it still is there. It still lingers.

Benji wonders how long things linger. Like poison.

“I’m not saying it were them,” Benji slurs in a way that only a handful of people in his life can parse. Maran is, fortunately, one of them. “M’saying s’another thing. The whales. But another fuckin’ thing.”

“You drank too much.” Maran points out, though his words mush together just as sloppy. “Leave ‘em out of your fuckin’…your melodrama. What’d they do?”

“Nothin’ but get ev- eve—eviscerated.”

“Evi—Eviscerated?” Maran pushes himself to his elbows. When he leans over Benji, he obscures the stars and the moon. HIs eyes gleam, liquid and syrupy as off it as he is. “Fuck’s sake, man. You are sloshed.”

“Wiped out!” Benji insists. “Gone. What’s left, anyway? Shoulda left the oil where it was, in ‘em — now we’ve got it in the land and the water and the lungs. Y’know people are gettin’ sick? N’it’s all worry about the plague come back. Ery’body old’s wringin’ their hands.” Benji blinks. “Dunwall’s fucked. Not just the whales.”

Maran laughs again. It sounds less humored. More concerned, a little higher in his head. “You’ve got to get a grip, mate.”

But Benji has seen what comes from the desire for a fist around something, even if that something is one’s own mind. He’d rather it unspool and worry and panic than keep himself properly contained. So few people talk about the struggles of the city in the way they sometimes do, when off a few glasses. Like a tattered, tragic history, suffering is a staple of Dunwall. A simple fact of reality. As unavoidable as the seasons, as the river’s currents, as the month of harvest. Nobody talks about why.

Benji thinks there’s a reason. He isn’t afraid to share it:

*

Dunwall is a thing rotted. To the quick, to the core.

And he doesn’t just say that now, because he’s stood in a line slowly shuffling. Each quiet occasional (never quick enough) shhhf of boots on tile is a machination of bureaucracy; that, to him, is just as evil as eviscerating an entire species.

Slightly less evil than the price he’s got to pay just for a copy of a piece of bloody paper to be put in his waiting hand — but only very slightly.

“That’s it, then?” He asks, staring down at the parchment. It’s got a neat roll of twine, an official shiny red wax stamp of the Empire’s symbol embossed.

“That’s what?”

He glances up at the official, seated on the other side of the window in a little clerk’s station. She’s old, but not ancient, with golden spectacles perched on her upturned nose and smile lines around her pursed, bored mouth.

“I mean —” Benji lets out a laugh, although it’s more huff than anything amused. Air in, air out. His hair messes beneath a clammy palm; they keep this particular government office so warm it’s stuffy. “Fuck. Oh, sorry — I mean, fuck.”

“Have I given you the wrong document?” She leans forward in her seat, peering back at him from behind glass so clean it’s nearly invisible. A long finger taps at the desk her side of the window, near the shiny metal slope beneath that allows them to pass things back and forth. “I’ll gladly check, but I’m sure that’s the correct one. The deed? I’ll check, but it’ll cost another two hundred to have it resealed.”

His eyebrows hitch. “Two — no. No, it’s right. Sorry. I just, it’s a big deal, isn’t it?”

The woman looks at him for a moment, then casts a glance over either shoulder. Then she leans forward until her breath softly fogs the glass.

“You’re holding the line up for me, lovey, but this bit—” she taps the desk, finger pushed into the groove where the rolled parchment has just been passed to him. “It’s been the talk of the office this week, do you know that? Good bit of land you’ve got, abouts Poolwick even? That market’s been nasty for decades, so few of us were privately — privately, love, it don’t bear repeating— excited to see it given back to family. Whatever strings you managed to yank to have this done, well. They must have been more ropes, yeah? You’re entitled to enjoy it.”

He beams at her properly now, unable to help the expression from slipping forth. “I intend to.”

She points a slim finger at him. Perhaps fighting a smile of her own: “And you keep it out of the hands of those industry beasts, you hear me? Won’t hear nothin’ about another factory being built on that pretty lake.”

Benji has no plans to build a factory, and assures her as such. He’d like to return his family there. He’d like to invite another family to join, and Maran, and maybe whoever Maran would like to invite, and maybe — well. He has time to figure the specifics out.

*

Only when he’s back in Maran’s room at the estate does he fully accept the reality of what he’s just managed to do. The clerk had no way of knowing how right she’d been, with that off-handed remark about pulled strings. The paper, wrinkled now from being excitedly clutched in his fist the whole trip back, holds more than just a bequeathed acreage sold to the empire several generations back. It’s years of work, of saving every single coin he could find, of picking labor shifts after a day guarding, of meetings and letters and delayed appearances before magistrates and solicitors.

The latter of which he only managed to successfully hire as representation for this goal (to sort the language of the law, something he’s never had neither desire nor respect nor time to pick apart) is Maran’s father. So, the man’s grandiose office of mahogany and golden trinkets and shiny lacquered imported trim should really have been his first stop.

Gabriel, as only Benji’s internal thoughts flippantly refer to him, is sat at the massive desk when the guards usher him inside. He knows firsthand how heavy that piece of furniture is — on more than one occasion, the duke had insisted someone “help” move it to catch light when his manic whims decided the sun was necessary to accomplish his day’s tasks. Or, task. Benji has only ever seen the man judging with hands tucked behind his back. Or signing a document. Or flipping a coin between his slim, tan fingers.

Benji knows this man hails from the western shore of Serkonos. Maran’s mother — the thought of whom pains him — from the east side of the island. Both had been pushed from these places with the northern islands’ settlement, vacationing elites, and Gristol’s upperclass. He thinks this is the reason the man had any interest in helping Benji secure his own family’s land once more. He knows it is the reason for Gabriel’s iron grip on Dunwall politics, his cultish drive for possession; for more and better and greater than what had been taken from his own lineage. He’d known power and prestige, had it taken.

Maran has his will. His stubborn, spiteful sense of accomplishment without the ugly tarnish of ambition. Benji hopes he stays that way. Benji wants to help him stay that way.

“It all worked out, then.” Gabriel says, even before Benji has taken the paper from behind his back and relaxed his dutiful, respectfully tucked pose. He makes himself smaller in the presence of this man — not because he’s scared for his own safety, but because Benji knows hate. He knew it far longer than before he’d met Maran’s father. And yet it had been Gabriel, his cruel and authoritarian reign on his own family, who made Benji understand hate.

Benji had been just eight the first time he witnessed one of the old bastard’s punishments. Just twelve when he realized: a father was not always the man who tucked the blankets to your chin, who retold an exciting bedtime adventure story with new details each time it was spun, who gently kissed your mother’s fever-hot forehead before tying an apron around his waist and happily undertook both share’s responsibilities of the house during the week she rested.

“In the end.” Benji says. He slides the paper across Gabriel’s desk. Although it hurts to watch, although he’d like to have the honors, although it’s his family and their acreage, he allows that wax seal to be broken by the duke’s thumb. He knows what Gabriel wants — what he expects. Benji will work the land back to baseline and then, because it’s a lovely plot in a good location near a burgeoning neighborhood of Poolwick’s growing enterprises, and because Benji has so far only ever been a grateful, loyal boy who follows the rules, Benji will sign over the property.

But Benji is only a loyal, rule following boy with certain eyes on him. And for certain strings to have pulled, ropes to be hefted, money to be made, his deal to be closed….Benji had moved outside the range of vision. It had required a path outside the constraints of legality and politics and respectful citizenship.

Benji had lied. Often. Benji took dubious jobs requiring hired muscle to move in the little hours of the night. Benji had smuggled, and stolen shipments of weapons, and rooted himself into some of the deepest, most rotted-through parts of Dunwall. And some of it, he had enjoyed.

The trickery the most.

So he smiles when he watches Gabriel unfurl the piece of paper. He thinks only of his plans for that land, and the look on the man’s face — far in the future — when Benji denies him the luxury of a purchase. Getting one over on this bastard will feel so good.

*

He keeps the secret for months. He’s saving it for a specific, special day. One that is always warm and golden in the height of summer. It’s one of his favorite days of the entire year, and for the past ten, he has never spent it alone.

Until now.

Gabriel has plans to open a resort in the hills above Karnaca, a sprawling vacation estate in which he can conduct business during the warmer months, when Gristol is even morewet and depressing than usual. Benji suspects it’s also being constructed as a destination to which he can send potential allies and partners. Only those, of course, with sway both social and material. Guests who will, by coercive wooing or outright threat, ingratiate themselves into a one-sided deal with a clear favor.

In true ruthless fashion, he’s offered hefty bonuses and leave to any of the current estate staff willing to travel for the summer and help see the Karnaca grounds is developed to specific, strict standard. Few of those who have this offer extended, including Xavier, decline it. It will put a sea between them for far longer than Benji is ever wiling to part from him, but —

“It’s fine. It’s fine. It will be fine.”

Warm hands clutch his cheeks. Xavier holds his laughing form in place while an absolute barrage of kisses are sundered over his face. There are wet tear tracks there, because despite the words, it will be the longest they’ve spent apart in years.

“It’s not fine.” Xavier says, rapid-fire between each of Benji’s assertions. “I’m going to wither away and die. I need to get these in —” he interrupts himself to smack a few more loud, wet kisses to Benji’s mouth. He squirms half-heartedly, squeezing Xavier’s ribs and shaking him as if this isn’t exactly where he wants to be.

“It’ll be good money.” Benji assures him, because that — it will be great money — is one of his few comforts. He wish he could say in addition to Xavier’s guaranteed safety, traveling in such a large and affluent group with familiar faces from the estate who care for him nearly as much as Benji himself. But nothing is assured in the isles but suffering and the need for money.

Fuck’s sake, he’s been in Dunwall too long. Maran is right about the melodrama, although he’ll die before he admits that.

*

They spend the week before Xavier’s departure largely in bed, of course. But also in their favorite places. Their chosen pub in the Financial District that boasts a chunk taken from the southern wall, weathered by age and rumored to be from the age of the last dynasty. Xavier, secretly, is a great fan of that particular tale; its romance and intrigue, its stalwart yet compassionate empress, and Dunwall’s victory over plague.

Xavier is hopeful like that. Benji is reminded of this again and again as they travel between their familiar roosts. The pub, the park, a botanical garden, an occult shop that serves as both an exhilarating terror to Xavier but unignorable temptation to his curiosity. They hold hands as they walk, or hook elbows together, or otherwise touch in ways previously deemed too intimate for public.

Xavier is hopeful, but when Benji is tugged laughingly down an alley for kissing (different, of course, then two warm palms slid together and must be private), he doesn’t feel that way at all. In fact, he feels quite the opposite. So stiff and panicked is he, even with Xavier in his arms and free with affection, that the kissing tapers off. The sweet, needy noises that he lives to hear slip into something questioning. Then, concerned. Benji doesn’t realize there are tears on his cheeks until fingertips touch to them, all the gentleness contained in his lover poured into that gesture.

“What?” Xavier smooths a hand up his chest. It becomes a gentle, comforting pressure around the back of his neck

Their noses nudge together and Benji takes a shuddering breath. It does nothing to help the strange tightness in his chest, the vice clutch of unsourced panic crawling up his throat.

“I don’t know.” He admits in a whisper. He moves his hands from their lusty grip to a slim waist in favor of a more chaste embrace. It feels good, maybe even better in the moment, to be held that way instead. And he’s so grateful for this — Xavier’s understanding, his desire and compassion alike — that the tears start afresh.

“Crying because I didn’t give you the last piece of taffy? Manipulative.” Xavier teases. They’re aside a busy street. The bustle of the crowd is a din of vendors and traveling merchants, out-of-towners and city natives alike. No one can hear them, but still Xavier pitches his pretty voice low. Just for Benji. Just for them.

The sweetness gets to him. He’s properly crying about it all, now.

“Shut up.” Benji rasps. His fists are locked in the back of Xavier’s jacket. “You like that shit better.”

“You like it better.” He argues, broad shoulders rounded and spine bent to put their faces together. He’s smiling. That wonderful, messy thing that flashes teeth whiter than any working class city boy has a right to have. Something like grief stabs strangely into Benji’s chest; he has no idea why, no knowledge of its source. He feels silly for it. There’s nothing darker there, nothing other than the vague looming he’ll be out of reach soon, a whole sea away. There’s nothing darker there, even though they stand on a paved Dunwall street, and there is always something darker, deeper, disgusting in Dunwall.

So Benji lurches up to bring their mouths together, a quiet sort of sob lodged silent in his throat.

This can’t be healthy, he thinks as they kiss and kiss, but he’s satisfied to find that another pair of hands clutch as desperately to him. And even when Xavier begins to make noise into his mouth, that fear in his chest stays tight and present. He can’t shake it. He chalks it up to the simple fact that they’ve never been apart this long. Not since they were young, not even for visits outside the city to family, on jobs, on other trips.

He wants to say something romantic, then. Something like I’ll miss you or I’m going to be here waiting or Did you know the fee to have a marriage certificate officiated in Gristol courts is only a little bit cheaper than a whole fucking land title?

Instead, he’s silent as they kiss again. It only lasts a few more seconds; sometimes, the way they come together feels too intimate even for this sort of tucked away privacy.

*

Xavier spends his final day in Dunwall with his family, and takes his final meal in Dunwall with his family, and sleeps his final sleep in Dunwall with his family. Much later, in his bitter recollection of those twenty four hours, Benji will reflect on the irony of these facts: it is his final day, final meal, final sleep at all.

And at this realization not yet to be had, Benji will experience something new — aside grief, that is. In time, the rot he knows infects the city will creep from its resting place beneath the cobblestone streets he strides. The choking miasma of suffering and tragedy and loss and horror will twine from the soles of his feet up, traveling like poisoning of the blood. Inside to out, always to follow, always to be a part of him.

One day, soon, Benji too will become victim to whatever lingering legend or curse has slithered into Dunwall’s being.

He’ll be worse for it. He doesn’t know that yet, though.

For now, sitting in the parlor with Maran, their shoes off and liquor once more uncorked in the absence of his father (gone ahead to Karnaca, as if he’d ever travel with the staff), all Benji knows is the sweet rush of alcohol.

“It’ll pass so quick.” Maran assures, not for the first time that evening. “And I’ll only have to deal with your moping for a season.”

Benji offers him a loopy smile and raised middle finger in response. Then, just as quick as it flit to his face, the grin falters.

“I—”

Maran groans loudly, fists pressed into his eyes as he tips his head back — and chair, so severely on its wobbling legs that only Benji’s heel hooked around one keeps him upright. “Don’t fuckin’ start! You kick off again and I’m in this state and then we’re both here weeping on the floor, worrying like hens.”

Benji sniffles to contain himself, at least for Maran’s sake. “You’ve stressed yourself more worried about him than you are bein’ in charge of this absolute shitshow.”

Maran makes a face then. A contrite, bratty twist of his brow, a bullish and annoyed pull to his mouth. “Xavier’s more important than any of this.”

Benji agrees. Benji scrubs his eyes with the back of his fist, and then opens his arms for Maran to crawl into. They fall asleep in the middle of the floor just like that.

His back hurts in the morning when they see Xavier off at the docks.

He wheezes when Benji squeezes around his waist, holds them tight together. And even though he’s the one leaving, doing something new, it’s Xavier who rubs a firm, soothing pet up and down Benji’s spine to ease that sleeping position strain.

Maran stands to the side, teasingly whistling and not making eye contact with the rare display of affection.

“Bring me taffy,” Benji mumbles into his chest, uncaring for the rain-slick fabric beneath his cheek. He can’t say anything else dancing around his skull, and it feels a silly thing to settle on, but:

Xavier response is a hearty, sweet laugh. The rumble of it vibrates into him. He holds that feeling until the ship disappears over the horizon, across the sea.

*

He wishes he could say that the moment it happens, he knows. That he feels it. That there is some deep and preternatural awareness that travels him, heart to veins to limbs and digits, of Xavier’s own steady beat. Of when it ends.

But he doesn’t know.

He isn’t there to see the flash of knife through the wind churning, ever constant currents, above Shindaerey Peak. He isn’t there to comfort the sting of it to Xavier’s cheeks, wet with tears and pale with fear. He isn’t there when blood pours between cracks of ancient stone to trickle down below, where the thin, corrupted veil separating the weak remnants of the void drink from the red rivulets. He isn’t there when the magic of the world sings anew, when a new entity is chosen, or when this age’s new cult discover there is no body to cart away into an accident scene worthy of covering their sacrifice — their crime. Benji isn’t there for the crackle of ozone in the air. For the way the wind stops, just briefly; the way the turbines still, and the way a burst of energy sends a ripple of outages throughout Karnaca’s upper district.

But only for a moment. There is profit to be made, and so there are backup generators and staff to see that they’re kept in good maintenance because it’s power, after all, that runs it all. And it’s power that leads Xavier, sheep to slaughter, and it’s power that slides the knife through flesh that ought to be kissed lovingly, and it’s power that ensures control remains in the fists of those this choice benefits.

Someone must be chosen, after all. It’s worked that way for as long as anyone can remember. Longer than the whales, the boy who came before, the one before that, the one before that. Even the deepest, oldest slate of the mountain itself forgets.

Benji isn’t there in those final moments, doesn’t feel the moment it happens although he will wish he did, and he isn’t there to know that the truth of this is revealed to Xavier in his final seconds.

What would you have become, if not this? Someone asks him, petting hair from his face as the blade descends. A dockworker, doomed to die of injuries at too young an age? A feeble, crippled thing with nothing to offer except burden? You’ll save us all this way, you know. The void is everything, holds us all in its cradle, and there must be someone to reign over its domain.

Benji isn’t there to know that this simple city boy is told he’ll be more, this way. Worse — he isn’t there to assure him that all he had been, prior to his death and rebirth, was good and wonderful.

Perfect, even.

*

The news comes in the form of a letter to the Wolffe family. It is Xavier’s eldest sister who brings the news to Benji. He will respect her forever for delivering it in person, rather than parchment, and suspects that the lack of tears in the moment are nothing more than a drought of them after an initial torrent.

There is a month left to Xavier’s contract at the Karnaca estate. Per its terms, the remaining money due goes to his family. They have plenty to put it towards, the number of mouths in that home.

One less, Benji thinks, and feels the threat of manic laughter so severe that he has to excuse himself immediately.

But, even as he withdraws to his quarters and locks the door and wedges a chair beneath the handle, the laughter never comes. In retrospect, he doesn’t recall what does: whether he cries or wails or tears chunks of his hair or mourns however gracefully or violently is lost to those initial few hours. They’re a blur of nothing when he reaches for them in his memories, and so he eventually stops trying.

He remembers Maran’s grief well enough, anyway.

*

Like his initial mourning, Benji can’t recall the first clue he had that something more foul than an unfortunate, reasonless tragedy had taken place. Surely at the instance that there was no body. Surely the quiet, guilty averted glances of the surviving staff that returned at the end of the summer. Surely it’s something. Surely there is a clue.

He is unwilling to admit that it’s a gut feeling, that sense of suspicion. Because what does it say, that he holds within him some knowing of something terrible, something rotten having taken place— and not a knowing of the exact moment the most important life to him was snuffed out?

*

A little over a week after the remaining staff returns — and one month after Xavier’s death — Maran catches him in the estate’s east wing, leg slung over an open window ledge.

Benji freezes and glances over his shoulder. They stare at each other for a long, long moment.

“If you fucking toss yourself to the yard, I swear —”

Benji snorts, even though he has felt devoid of humor for so, so long. Devoid of anything but…well. Nothing, really. He’s only felt empty, and so the recent wash of rage and suspicion and paranoia had been welcoming. Like a warm, familiar embrace.

“M’not killing myself, you arse-faced bastard.” He fires back, tugging the dark cloth from around his nose and mouth so Maran can better hear the insult.

Maran crosses the room in a few strides, bare feet padding across parquet without any thought to how loud he’s being. His skills of stealth and diversion are only so honed to the point of occasional sneak-outs and late night trysts off the estate require. Maran isn’t like him. Maran doesn’t know how unalike they have grown to become. And he might have his own suspicions, but Benji doubts they run as deep and vile as his own.

As he’s enfolded in a tight hug, Benji imagines the rot of Dunwall creeps from him onto the edges of Maran’s soft sleep shirt. Stains it and the little thread of embroidered vines gracing its edge.

He drops his head to Maran’s shoulder, squeezes his eyes shut, and then shoves his best friend away by the shoulders.

It’s so strong and unexpected a motion that Maran doesn’t just stumble backwards; he trips toe to heel, arms pinwheeling, and falls on his hip with a loud, sharp cry.

Hate me, he thinks. Hate me, hate me, hate me.

“What the fuck?” Maran hisses, maimed more to the heart than anything else. He stares up at Benji from his prostrate place on the floor, brows pinched in annoyance. Otherwise, his expression is nothing but wounded.

“I’m going to Karnaca.” Benji blurts. He hadn’t meant to reveal anything. He’d meant to slip out, unseen. But —

Maran gapes at him. He starts to gather himself, to get to his knees — and if he does, if he comes forward, if they touch again, Benji knows — Benji knows himself.

“Benji —”

The stars no longer twinkle above the city skyline. Although luminous, they’re distant. They’re muffled by the smog and smoke and ever-flickering lights. When they were children, before oil was replaced by a new wave of technological innovation, the constellations could be easily picked out. Now…

“Finally sorted my shit. Bucked up enough this year. I was gonna—” He thinks about a piece of parchment crammed into a fireproof safe beneath the floorboards of his mother’s home. He has resigned himself, perhaps out of some sick sense of duty, never to step foot on that land. He can’t bring himself to walk it alone. “I told Saha and everything. Had a script. Made her read it, wanted to be sure it didn’t sound —” he chokes up then, clears his throat. “I was going to ask. I — I have to go.”

Maran has fallen silent. And Benji knows he shouldn’t, but he casts another look over his shoulder as he swings both legs out the window. Maran kneels, hands uselessly loose in his lap. His eyes are shiny with rapidly welling tears, and now Benji has to look away.

“Please don’t, Benji. Please.”

And that plea comes so, so close to enough.

*

Benji’s determination is all that it takes to begin unweaving the underbelly of Dunwall’s shadier dealings. He grew up in the city, already aware of the shadows — but now he has reason to delve into them, reach in and pluck specifics. He has suspicions that need dragged into the light of day, and it’s only the fierce (perhaps mad) drive to accomplish this that allows him access to criminally-adjacent interworkings.

When he catches the Rhoades girl around her slim throat, he has to temper how hard he shoves her against the ugly wallpaper. She’s a sleight thing, gracefully and fragile in that birdlike way some noblewomen tend. He doesn’t want to hurt innocents, no matter how intwined they are in this work. It’d be hypocritical. It’d be wrong.

(And still, he isn’t sure how long that line will remain uncrossed. He has to know.)

There’s nothing meek or caged about the way she angles her chin and clamps down on his wrist hard enough to draw blood. Benji clenches his jaw against the sharp pain, waiting for the bluff — and she cedes first, if only to make a disgusted face at the metallic taste on her tongue. Benji has never dealt with this broker of information before, in his occasional black market dealings, but she has a reputation.

He spots the source of those rumors in the fierce, narrowed judgement aimed from her pretty eyes.

“Name your —”

“I’ve no price you can match.” Benji interjects. He lets her go and steps back so that she can slump to the ground with at least a bit of dignity, but she doesn’t do more than wobble on long legs. A slim, well-manicured hand wraps around the flushed skin of her own neck, but that soothing touch is the only weakness from their encounter she displays. Benji is, begrudgingly, impressed.

“If it’s blood you’re after just make it quick. And make sure to arrange me some way nice. There’s a chaise I like in the library — but I’m telling you now, if I’m not found dead and pretty, I’ll haunt you until you wish it’d been you.”

Alright, fine. He likes her.

“One of your little network’s agents is working for Giarrizzo-Cohn. She’s better at pretending to be a skilled maid than keeping secrets, bless her.” Benji holds his palm flat, even between them; she’s taller than him by several inches. “About here? Curly hair. From Tyvia, I think?”

He’d tried to fuck someone from Tyvia, recently. Auburn hair (wrong shade). It had gone no further than a hand (wrong size) on his shoulder for Benji’s stomach to turn enough to make him flee.

At the mention of Odette (and probably the cruel insinuation of her safety at stake), Matilda Rhoades’s face shifts entirely. The bravery fades into obvious concern, although the rage still simmers beneath the surface.

“What do you want.”

Benji shrugs. “I’m headed to Serkonos. I need to know where Lethe holes up.”

She snorts, which seems to him a very unladylike thing to do. And yet it makes him think of Saha and her freely given amusement; it’s a flash enough of recognition to soften him more. She’s dangerous, if not the way brutality is — but charm.

“Do you understand how very upset a broker of Lethe’s caliber will be if I give out information like that?”

“So you know.”

Matilda opens her mouth then closes it. “I just woke up. You pulled me from bed.” She squeezes her eyes shut and pinches the bridge of her nose.

Benji raises his hand in cheeky apology. “Not at your best. Things slip.”

Matilda gestures towards a little folding desk in the corner of the room, and Benji goes to it — without turning his back. When he returns with a dull, sharpened-short pencil and notepad, she scribbles on it before tearing the paper and smacking it into his chest.

“There.” She waves her hand at the door. “Close it on your way out, you sad fucking goblin. And say hello to Maran for me, will you? He owes me gossip.”

*

Benji makes the mistake of falling into fitful sleep on the ship over. Just one quick, short nap. One snap of his eyes shut. When he wakes, his pack is gone from between his ankles. He had tied the strap tight around one calf, and still the thief had managed to finesse it without waking him. If he were in a better state of mind, he might respect it. But he isn’t — and because he knows only one contact on the whole accursed isle, because the fears them, Benji winds up in a tavern with the only coin lining his pockets. He’d been traveling light, after all; he’d embarked on this trip with little thought as to where it would lead him, if anywhere but the grave, when it was over.

He can only face Lethe several drinks in.

Until now, they have exchanged dealings through only written correspondence. The letters come coded; he takes them to Dr. Sullivan for a price.

When Benji drops through the skylight into the messy studio, it seems that his arrival is expected. He had no idea what to expect of this strange and mysterious merchant of information. He is not expecting an artist, and he is not expecting the fantastical array of gore on canvases scattered about the room. Some of them span from floor to ceiling; others are no larger than his palm. All of them are stomach-churningly detailed, rendered with care, skill, and a suspiciously precise amount of detail. These are works with love in every brush stroke

“Kitschy.” Benji comments into the darkness of the studio. “How much d’you budget for red pigment, I reckon?”

“More than your life is worth.”

Benji turns to the voice, which sounds to him as androgynous as its owner. Lethe, or the person he assumes has taken that moniker, steps from the shadows like a wisp, a phantom. They are as light as one; a blank canvas to be projected upon, to be painted by others. Benji is no painter. He has no idea which colors he’d used to begin to render them. In the low light, he sees only the glint of silvered skin and hair, and eyes a muddy ruby-red.

“Rude. Haven’t done anything to you, have I?”

Lethe spreads their arms, striding into the slice of moonlight. They seem to disappear, plains of a wide nose and full lips only visible in slight shadow. Anonymity makes sense, considering their — condition? He’s never met anyone that looks the way they do.

“You broke into my studio.” The broker says, gesturing with one hand to their surroundings. “If you had good intentions, you’d visit the gallery like the rest of my patrons.”

Lethe rounds the diameter of the moon’s spill. Benji mirrors it slowly, keeping them at the same distance. The hair on the back of his neck is standing on end.

“What do you want?”

“Just like that?” Benji fires back, masking twinging nerves with as much cheek as he can muster.

Lethe glances towards the wall behind him, and stupidly, he looks too. A clock ticks gently, both arms pointed upright. When he turns back, Lethe stands directly before him. He finds a step back impossible. It isn’t often Benji has felt…cornered.

“It’s late.” Lethe correctly points out. “And I have a showing in the morning.” He must imagine that twitch of their mouth. “If you don’t mind.”

“I’m looking for someone.” Benji admits, and winces. He hopes not too much is betrayed there, in that look, because somehow it feels as though all of the pain he’s held onto since Tess visited bleeds in. “Or, uh. I’m looking into what happened to someone.”

*

The mystery unravels quickly, once Lethe pulls that initial thread for him. What he discovers in the subsequent weeks, is done in a period of depraved obsession that he spends either in a rented room, researching into the long hours of the night, or roaming Karnaca’s backstreets and hovels and paved streets in neighborhoods of wealth alike. The whole story is a bit more nefarious than the murder of one poor boy from Dunwall. And, if perhaps he had a bit of distance from the details, it would be downright horrifying. A cult intent on restoring controversially powerful magic — the weavings of the world — seems an awful children’s story. The sort meant to sway little ones onto the right side of morals, of society.

A fantastical notion, in of itself. It’s a bit late for Benji anyway. He stops recognizing the face in the mirror. Soon, he’ll stop looking at all.

The first one — a proper cultist, judgment bequeathed by way of the myriad of writings in her office and the vast amounts of books on the void stacked in the adjoining library— happens to be one of Lethe’s many patrons. He’s expecting a shadowy cloaked figure. A beautiful witch, maybe. Someone kept forever young by dealings with the powers of the void. Someone more concerned with their own life than that of an innocent.

She isn’t any of that. She’s a kind looking old woman with pictures of grandchildren in golden frames tacked to the wall and knots in her gray-touched hair. He suspects it’s because several of her fingers are curled towards her palm, gnarled by the touch of arthritis. It must make it hard to hold a brush, and the pride of her upbringing must make it difficult to ask for help. He discovers later that she was from Tyvia. Same town as Odette, it turns out — he wonders if she moved for the warmer air. Better for the joints, he’s heard.

When he corners her in her sprawling estate’s quaint study, she drives a knife tucked up her lacy sleeve into Benji’s side. He pulls it out with a grunt and pushes it through her heart.

It certainly isn’t painless, but he makes it quick. It’s the only one of the subsequent six lives he takes that is. By the end of it, on the other side, Benji returns to Dunwall and wishes he had saved that mercy for himself. He’s only sick that first time, emptying his stomach in a back alley several blocks from the Tyvian elder’s estate. He’s only sick the once. That first life. He’s heard it before, and is only a little horrified to find it true: after one, the rest are easy.

He thinks that maybe he was right, in the end. There is something rotten in the city. It corrupts, and it takes, and it kills, and it is horror. It is suffering, inescapable; and rather than fear it has seeped into him, Benji knows. Benji knows a lot, now. Namely, that there is something rotten in him.

The worst of it is maybe the secret he keeps tucked closest to him, only to him. It isn’t one meant for brokers, or traded for coin. It is the sort of secret whose worth is more precious to him than any amount. Because it would do more than devastate Maran to know the role his own father had in a ritualistic sacrifice, one of his friends. It’s the kind of secret he can’t carry. It’s the kind of secret Benji can. Better the rot is shouldered by him than someone else. Someone innocent.

But then again, his mind winds to him late at night, curled and knees-tucked alone in a bed that had once barely fit two, what had innocence done for Xavier?

#writing#bp#xw#mgc#mmr#bp x xw#dishonored au#elliot was quicker to the angst for this au than i was#so i had to get revenge#very sorry everyone u are collateral

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

guys add me on moshi monsters rewritten my username is maedhros

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 y/o self has possesed me and im now obsessed with virtual world games again

if anyone else plays MMR my username is psii and idk how to change my monster name so i think its the same so yea feel free to friend XP

#join me#moshi monsters#moshi monsters rewritten#mmr#its so funny to me that most of the players are 16+#we're all living our childhoods again#virtual world#i started playing 3 days ago so my room and zoo is kinda meh#+ my poppet has default colours 😭#might change to katsune later idk

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Street Fighter: Alex by Dan Toonas aka MMR

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

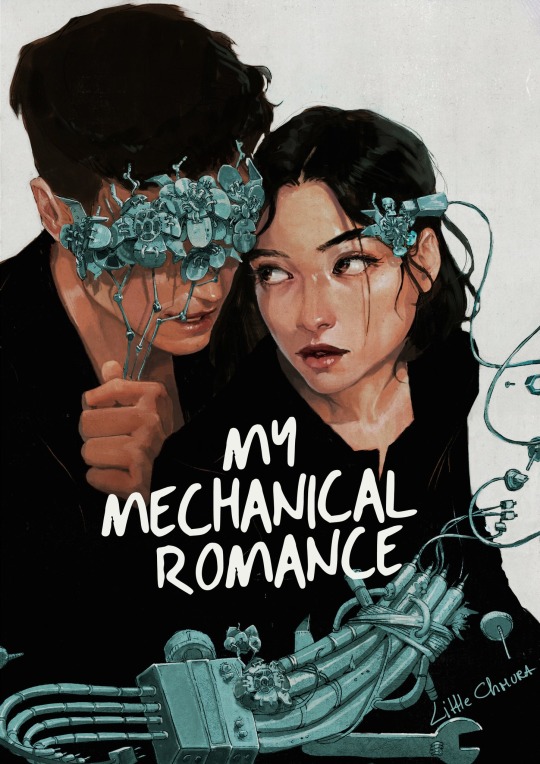

HAPPY BOOK BIRTHDAY TO MMR! 🦾💗 CONGRATS TO @olivieblake on the release of her first YA novel! Everything she touches turns to gold 💛

here’s my review: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/4564193045

Art by incredibly talented @littlechmura ! ⭐️🫶🏻

#mmr#my mechanical romance#alexene farol follmuth#olivie blake#new release#ya#art#gr review#book review#little chmura

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not saying Twisted Metal is the best tv show adaptation of a video game. But I'm also not, not saying that. You know?

#twisted metal#twisted metal tv show#peacock original#twisted metal peacock#twisted metal video game#twisted metal black was the best one and also the only one i played#sweet tooth#sweet tooth the clown#video game#adaptation#tv adaptation#tv show#tv review#podcast#mixed media reviews podcast#mmr#mixed media reviews

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes babygirl just has to kill people and we all have to let her (matilda belongs to @unknownangels)

#my art#dont look closely at this it was meant to be a ten minute sketch and then i slapped some colors on it#mmr

8 notes

·

View notes