#keyworddefinition

Text

Keyword Definition

Selfies

Unfortunately these days the term selfie has been given a negative connotation. Selfies are photos that people take of themselves, usually with the intention to post on some form of social media. Many internet users, specifically an older demographic, tend to criticize selfies for being shallow, superficial, and of no useful necessity. There is often a misunderstanding that selfies are a modern invention when in truth, they have been around for centuries simply through different mediums and with different given names.

The Origin of the Selfie

It is not certain who exactly coined the term, but the Oxford Dictionary dubbed it the “Word of the Year” in 2013. Despite the term being relatively young, the concept dates back centuries. Self-portraits have existed well before iPhones and Snapchat. One could argue that the act of recording one’s own image has always been commonplace, but the medium has changed over time. However, if we are to say when the first “selfie” as we know it happened, we must thank the early photographers. A self-portrait taken by a man named Robert Cornelius is recorded as one of the first people to photograph themselves. This photo dates back as early as 1839.

Anyone familiar with Russia’s lost princess, Anastasia, would remember that she was one of the first young people to take a selfie. She even sent this photo to a friend, proving that the need to share photos with friends was common even in 1914. If one looks at the photo, they can see it is not unlike a common mirror selfie one would post to Snapchat today. If Anastasia were alive today, she would have most likely had posted that photo to a social media site.

Many have laid claim to posting the first selfie, but sources have mixed answers on this. Some say it was a group of friends in Australia, some say it was a drunk man, and Paris Hilton adamantly insists that it was her. All leads are inconclusive (Bellis).

Selfies as an Art Form

As I mentioned before, selfies are a type of self-portrait. According to an article titled Art at Arm’s Length: A History of the Selfie, selfies are structurally sound and should be considered an art genre of their own. This makes sense to me, as selfies are a form of expression and more or less have a set of rules in the way that are meant to be presented. This article says that while selfies are not exactly portraits, they are very similar. The fact that they are not exact does not stop them from being their own genre. Selfies have similarities that give them a copy-able format, and an identity in the art world. They are a very present act, it is impossible for the process to be an accident. For this reason, creators know that the results will be instant and the photo will be viewed quickly by many. The act of a selfie is a performance piece, allowing others into a small fraction of our live through self-expression. There was a moment in this article that I adored basically calling selfies a “folk art” created by and for the people. Having the tunnel vision of only thinking of the present, it is hard to see how selfies contribute to the grand scheme of things. However, it is incredibly useful to have these moments of vulnerability recorded for future use. Who knows what the future could say about our culture looking back? (Saltz).

Forms of Selfies

Typically, selfies posted online have a very formulaic format. The camera is no more than an arms length away, the arm a significant feature in the photo. For many, the inclusion of the arm is what makes a picture inherently a selfie. For the most part, these types of selfies will have the subject’s face looking to the side, working with their angles. This is the generic selfie in which the subject expresses their mood, location, and whatever clothes can be seen from the top angle (normally just the torso). These will often be taken alone and be close-up enough that the main focus is the subject, but the viewer can still see where they are. Group selfies are a form of expression as well, often with the vision coming from the one asking for the photo. The intention here is to show off who the subject is with and where they are sharing this moment together. Performance selfies are selfies deliberately made to entertain and come with a wide variety of examples. From the Selfie Olympics that were made to see how wild the circumstances of the selfie could be, to the #followme movement which featured a girlfriend guiding her boyfriend through beautiful scenery, to outfits of the day in which the subject showed off their complete outfit in a mirror (Frosh).

Selfies Today and Tomorrow

Selfies have evolved over time, especially with the power to manipulate them. The shift of social medias also has a huge effect on the way they are taken. Apps such as Instagram and Snapchat made filters a very important tool for the medium. So much so that if a picture isn’t using one, the user is proud to caption it #nofilter. Since the rise of apps like Snapchat, selfies have had even more room to become art. The paint feature allows the user to draw anything they want on their pictures. Filters allow users to play around with their image and express themselves accordingly. With the recent update, Snapchat has taken a hit from their user base. Many find their favorite medium of expression is inaccessible and clunky. It will be interesting to see in real-time how this affects selfie culture in the future. Perhaps filters will become a thing of the past. Only time can tell. While the method and style of the selfie may change, its label as a genre will remain.

Works Cited

Bellis, Mary. "Who Invented the Selfie?" ThoughtCo, Jan. 30, 2018, thoughtco.com/who-invented-the-selfie-1992418.

The Gestural Image: The Selfie, Photography Theory, and ...www.bing.com/cr?IG=6638D05751FE43888716FF5AEAFE0331&CID=26CA2810247A63A533C2238B25D562E7&rd=1&h=oSfBtke7XFmEMZJC8G95vlpIUO1wM8ikqGp_YLu4574&v=1&r=http%3a%2f%2fijoc.org%2findex.php%2fijoc%2farticle%2fviewFile%2f3146%2f1388&p=DevEx,5068.1.

Saltz, Jerry . Art at Arm’s Length: A History of the Selfie. 26 Jan. 2014, www.cam.usf.edu/InsideART/Inside_Art_Enhanced/Inside_Art_Enhanced_files/6D.Art_at_Arm%27s_Length_%282014_article%29.pdf.

-SA

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tool-Tipp: SeoTagMonster

Die passenden Keywords im Online Marketing zu finden, damit tun sich viele schwer. Dabei ist es abhängig von den Keywords, ob ein Produkt Erfolg hat - oder eben nicht.

Das Problem hierbei ist, wenn man es gewohnt ist im Internet zu arbeiten, dass man ganz anders die Suchmaschinen benutzt, als jemand, der wirklich gezielt nach etwas sucht. Hier müssen wir umdenken. Aber genau das ist das Problem, was viele haben. Nach was suchen die Leute? Wie benutzen die Google und andere Suchmaschinen? Benutzen sie die Spracheingabe? Oder tippen sie auf die alte herkömmliche Weise?

Fragen über Fragen!

Es gibt wahnsinnig viele Tools im Internet, die einem die passenden Schlagwörter ausspucken. Doch diese sind meist sehr teuer und haben viele Funktionen, die man vielleicht gar nicht unbedingt braucht.

Meinen Beitrag hier beziehe ich auf das Kindl- Business.

Denn wie in jedem anderen Business, das im Internet stattfindet, sind auch hier die Keywords von unheimlicher Bedeutung. Ohne passende Schlagwörter lässt sich auch das beste Buch nicht verkaufen.

Wenn man es ganz nüchtern betrachtet, sind der Inhalt und das Cover nur zweitrangig.

Ausschlaggebend für den Erfolg eines Buches sind in der Tat die Keywords.

Kann man versuchen, die passenden Keywords selbst zu finden, immer wieder neue auszuprobieren und zum Schluss entscheiden, welche denn davon funktionieren - und welche nicht.

Es gibt aber auch noch eine Abkürzung.

Ich selbst nutze für meine Kindl Bücher ein Tool namens SeoTagMonster.

Dieses Tool zeigt mir alle relevanten Schlagwörter an, mit denen ich meine Bücher taggen kann.

Bevor ich aber weiter das Tool eingehe, muss ich noch dazu sagen, dass man es nur nutzen kann, wenn man eigene WordPress Installation hat. Denn das SeoTagMonster ist eigentlich dazu konzipiert, Keywords für einen Blog zu finden.

Doch warum das Tool nicht für seine eigenen Zwecke nutzen?

Das SeoTagMonster sucht die passenden Keywords zu meinem Stichwort heraus. Dabei bedient es sich nicht alleine an Google, sondern auch an Bing, YouTube und Amazon. Somit bekomme ich die allerbesten Schlagwörter heraus, nach denen häufig gesucht wird.

Diese kann ich mir dann wiederum in meinem Beitrag kopieren und von dort aus dann nach Amazon Kindle.

Natürlich ist das ein kleiner Umweg, aber für einmalig 39 € kann man dies gern in Kauf nehmen.

Man kann es als Vor- oder auch Nachteil sehen, dass hier zu den Suchergebnissen keine Zahlen stehen. Sprich, du wirst nicht sehen, wie viele Personen nach einem bestimmten Keyword suchen.

Hier ist dann selbst Mitdenken gefragt. Aber ich denke, das sollte nicht schwerfallen, denn du weißt schließlich am besten, was dein Buch beinhaltet.

Ich nutze das Tool inzwischen seit eineinhalb Monaten und kann eine Steigerung meiner Verkäufe sehen. Bei Büchern, die ich nicht auf Keywords optimiert haben, finden nahezu keine Verkäufe statt. Bei jenen Büchern aber, bei denen ich das SeoTagMonster im Einsatz habe, kann ich eine zunehmende Steigerung der Verkäufe sehen.

Aus diesem Grund kann ich wärmstens empfehlen, weil es wirklich deine Arbeit erleichtert und du den Einsatz recht schnell wieder rein hast (bei mir war es nicht einmal ein halber Tag).

Wer mehr über das SeoTagMonster erfahren möchte, der sollte einmal auf den nachfolgenden Link anklicken.

(Wie bereits erwähnt, es ist auf Webseiten konzipiert und darum diese Seite auch dafür ausgelegt. Ich selbst nutze es hauptsächlich für das Kindl- Business)

Achtung: Wenn man die Webseite das erste Mal besucht, gibt es einen Rabatt von 10€, das heißt, ihr bekommt das Tool für 29€. Das Angebot ist zwei Stunden gültig und läuft danach ab!

Beitrag anhören

Read the full article

#AmazonKeywordRecherche#GoogleKeywordPlanner#GoogleKeywordRecherche#GoogleKeywordSuche#KeywordAmazon#KeywordAnalyse#KeywordAnalyseTool#KeywordAnalyseWebsite#KeywordAnalyser#KeywordAufDeutsch#KeywordChecker#KeywordDefinition#KeywordDomainSeo#KeywordErklärung#KeywordEverywhere#KeywordFinderAmazon#KeywordFragen#KeywordFree#KeywordGenauPassend#KeywordGenerator#KeywordGeneratorKostenlos#KeywordGoogleSearch#KeywordGoogleTrends#KeywordHäufigkeit#KeywordIdeen#KeywordIdeenFinden#KeywordInContext#KeywordJobSearch#KeywordJournal#KeywordKannibalisierung

0 notes

Text

Keyword Definition: Motivational Posters

Motivational Poster: an image with accompanying text intended to influence a viewer’s attitude or behavior, particularly to motivate a viewer to reach a particular level of performance or display a particular characteristic through the use of emotional appeal.

“Hang in there, baby!”

“You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

“Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.”

Motivational posters can be seen everywhere from the classroom to the work place to your very own phone. These posters can be physical or digital, but they all display a quote (like the ones above) set against a photograph or illustration. The purpose of these posters is to influence their audience’s attitude or behavior, often to achieve a particular level of performance. Motivational posters are so ingrained into American society that certain motivational designs and quotes have undergone thousands of remakes and parodies—take for example the image of the “Hang in there, baby!” cat above which was remade in a Simpson’s episode! Yet even though motivational posters may seem cliché, they have not always been the norm, especially in regards to motivating employees in the workplace.

Seiders, Motivational Aesthetics, and Mathers & Company

Prior to the twentieth century, advertising and propaganda depended largely on text and written rationale, following a Victorian tradition that largely distrusted images as a form of persuasion. Magazines rarely featured pictures, except those that elucidated complex technical issues explained in the articles. At the turn of the century, image began to take on a more important role in American society, especially the use of posters. Posters had previously been considered an irrelevant, feminine medium, but in 1915, the U.S. National Safety Council began a nationwide poster campaign, followed by the U.S. government’s propaganda campaign during WWI (Gray, 77). These campaigns began to legitimize the use of posters as a professional medium.

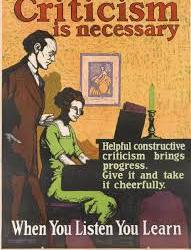

Following the war, the business community adopted the same illustrative practices to promote efficient work environments that the national government had use to promote “national service and patriotic sentiment” (Gray, 78). Seth Seiders’ Mather and Company was the first private company to create a nationwide poster business in 1923, capitalizing on the dawn of the humanist approach and industrial psychology, which were both being implemented by managers in the workplace. “New literature proposed that management should take into account the worker's emotional needs, aspirations, and desire for ‘fellow feeling’— meaningful relationships with workmates—in its effort to win over the worker's allegiances, mitigate industrial conflict, and increase efficiency” (Gray, 79). Seider saw this new movement as an opportunity to market posters and pamphlets that appealed to worker’s emotions in a way that created a positive environment, motivated workers to improve efficiency, and “advertise(d)” the behaviors which managers expected from their employees (Gray, 80). Seiders’ business contributed to a new culture of visual education in which image began to supercede text as the main form of advertising and public information dissemination in the twentieth century (Gray, 80),

“At the height of its success in the late 1920s, Seider claimed that (Mathers) was supplying over 40,000 firms… (whose) customer base stretched from coast to coast in the insurance, commerce, transportation, cannery, communications, banking, sales, coal, and rubber industries,” according to an article about Seider’s business practices by David A. Gray (Gray, 77). The posters themselves embodied artistic movements of the turn of the century, and incorporated bold colors and images accompanied by instructive text (see example below). This developed the start of what Seider called motivational aesthetics, the combining of motivational texts or quotes with appealing images.

Mosby’s Great Performance Company

The next significant evolution in motivational posters was in the 1980s and 1990s with the introduction of Mosby’s Great Performance Company. This company had its start in the health care industry, but eventually developed motivational posters whose main purpose was worker incentive. These posters are recognizable by their photography images framed by a black border with a motivational quote or word written in the bottom center. These posters were a result of trends in “foreign competition, corporate downsizing, new emphasis on quality, and racial and gender tensions,” but were targeted towards manager performance rather than hourly workers like posters in the past, introducing a new definition (Smithsonian Libraries). Today these posters are some of the most recognizable in the motivational aesthetic canon.

Motivational Posters Outside of the Workplace

Motivational posters are also frequently used in classrooms and educational settings for the same purpose as when they are used in work environments; to influence behaviors and attitudes. The behaviors that increase efficiency, collaboration, and productivity in a company are the same ones that create a harmonious educational environment. A differentiation must be made, however, between motivational posters used in educational settings and educational posters. Educational posters’ purpose is to educate by presenting new or complicated information in an easily accessible and visually appealing way--similar to an infographic-- whereas a motivational poster is focused on behavior and attitudes. Both educational and motivational posters fall under the larger category of visual education and are similar mediums, but they differ in the messages that they deliver.

Motivational posters have been proven to encourage healthy decisions like taking the stairs or buying healthier beverages when placed in strategic locations, operating in a manner similar to propaganda by encouraging public consciousness (Tay). Additional evidence of motivational posters’ relationship to health will be discussed in more detail later in the article.

Online Motivational Posters

With the dawn of the internet, and especially social media platforms like Instagram and Pinterest, motivational posters have taken on new form as digital images. These images may not be physical “posters” per say, but they do fall under the same categories of motivational aesthetics.. Images from the Internet have the ability to be downloaded, printed, shared, viewed, commented on, liked, and displayed on desk tops, lock screens, or any other digital platform that you can think of, changing the way in which motivational posters are viewed and interacted with.

The format of motivational posters online varies greatly, but the majority still adheres to the traditional motivational text/image format. Dennis Tay analyzes what he considers the previously unexplored area of online motivational posters in his article “Metaphor construction in online motivational posters.” In his sample of 900 online motivational posters selected at random from the three top-searched online results for “motivational posters,” only 4.8% relied on visuals alone (Tay, 110). This statistic reinforces the importance of text/image combinations when distinguishing motivational posters from other online images. Tay also brings up the topic of demotivational posters, a subset of online images produced in a style that parodies traditional motivational poster formats but that include negative text. (Tay, 110).

Newer forms of media circulating on the internet are memes, humorous images, videos, or pieces of text that are copied (often with slight variations) and spread rapidly by Internet users. Often memes take the forms of images with text written over them, in a similar aesthetic approach as a motivational poster. However the differences between the two forms of media lie in their messages and purposes; memes are intended to connect audience members to one another by allowing them to share in a joke, feeling, or emotion while a motivational poster is intended to influence attitudes or behavior. Some memes are intended to influence attitudes and behavior, but because they extend beyond this purpose and have their roots in humor, they cannot be categorized with motivational posters.

“Do They Really Work?” Societal Effects of Motivational Posters

It is difficult to determine whether or not motivational posters achieve their attended effect of improving the workplace environment. Studies of motivational posters focus on their history or content, but not specifically on their overarching societal effect. Yet since motivational posters have continued to be used in the workplace for close to one hundred years and have evolved to such a degree, they must be making some sort of impact.

In the author’s opinion, the power of motivational posters lies predominantly in their appeals to emotion. Pathos is one of the strongest rhetorical devices, and since motivational posters typically invoke idealized images and text, they play into this rhetorical strategy. They can also satisfy the emotions of the manager or person who puts them into place by allowing the person to feel as though they have done something to improve the lives of their employees or audience, resulting in positive reinforcement for the action. Motivational posters powers also have a basis in psychology. In the book Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation : The Search for Optimal Motivation and Performance, authors Sansone and Harackiewicz discuss how it takes a balance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to optimize both performance and experience (Sansone & Harackiewicz, 3). Too much extrinsic motivation can dissuade or eliminate intrinsic motivation (Sansone & Harackiewicz, 3). Motivational posters are classified as extrinsic motivation because they are displaying a message that is external to the viewer. However because of the text’s motivational nature, posters can also inspire intrinsic motivation by empowering the audience into feeling that their life is in their own hands, they have an internal locus of control.

Despite their name, motivational posters do not always motivate viewers in a beneficial fashion. Online motivational posters are frequently used by health and fitness bloggers in a recent trend called “fitspiration,” a combination between “fitness” and “motivation.” Images with tags like #fitspiration or #fitspo, a.k.a. fitspiration content, is defined by researchers Lea Boepple, B.A. and J. Kevin Thompson, PhD as “content promoting fit/healthy lifestyles…includes objectifying images of thin/muscular women and messafes encouraging dieting and exercise for appearance rather than health, motivated reasons (Boepple & Thompson). Oftentimes this content takes the form of traditional motivational posters, with text overlaid against an image of a lithe, young woman. In a content analysis of fitspiration websites by the same authors plus Ata and Rum, the authors analyzed the images and text found on these websites shared many of the same qualities as pro-anorexia or “thinspiration” websites which have been linked to poorer body image and higher likelihood of disordered eating (Boepple et. al.). In a similar study published in Cogent Social Sciences in 2016, Hefner et. al. found that fitspiration images on microblogs like Instagram and Twitter were related to disordered eating symptomology because of their encouragement of dieting and restrictive eating (Hefner, et. al.) From studies such as these, we can the particular way in which motivational posters combine image and text to influence our attitudes, behaviors, and even our health.

Motivational posters have evolved in style and persuasiveness since their introduction to the American workplace in the 1920s, but their messages and purpose remain largely the same. With the rise of new technologies, motivational posters have transcended physical forms and found new relevance as digital images shared throughout the Internet. Whether they are used seriously or parodied, motivational posters affect the social world in a manner that is unique to its particular medium by combining text and image to influence attitudes and behavior.

Works Cited

“American Enterprise Exhibit: Posters.” The National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Libraries, americanhistory.si.edu/american-enterprise-exhibition/new-perspectives/work-incentives/posters.

Boepple, Leah, et. al. “Strong is the new skinny: A content analysis of fitspiration websites.” Body Image, vol. 17, 2 Apr. 2016, pp. 132–135. Social Sciences Citation Index, eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=3dc002a5-79ba-46e2-9393-9632c60eb20f%40sessionmgr4008&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=000377728500016&db=edswss.

Boepple, Leah, and J. Kevin Thompson. “A Content Analystic Comparison of Fistpiration and Thinspiration Websites.” International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 49, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 98–101. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=4&sid=9f0fe3ef-5043-48fa-861a-18cb1a6804a5%40sessionmgr120&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=112198047&db=pbh.

Gray, David A. “Managing Motivation: The Seth Seiders Syndicate and the Motivational Publicity Business in the 1920s.” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 44, no. 1, 2010, pp. 77–121. Art and Architecture Source, eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=3&sid=1f6f3a9c-5d78-478e-9a9c-292c71c23366%40sessionmgr102&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=505319260&db=asu.

Harackiewicz, Judith M., and Carol Sansone. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation : the search for optimal motivation and performance. Academic Press, 2000. UF data base, eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=fbd0552f-7ccc-4ba4-9ba5-3c89933557b1%40sessionmgr103&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=ufl.020328511&db=cat04364a. (ebook)

Hefner, Veronica , et al. “Mobile exercising and tweeting the pounds away: The use of digital applications and microblogging and their association with disordered eating and compulsive exercise.” Cogent Social Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2016. Directory of Open Access Journals, doaj.org/article/e70a44e9c39043e9921f92aa6e50bf62 .

Tay, Dennis. “Metaphor construction in online motivational posters.” Journal of Pragmatics, vol. 112, Apr. 2017, pp. 97–112. Science Direct, www-sciencedirect-com.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/science/article/pii/S0378216616305665.

-RE

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keyword Definition: Contemporary Dance

Define Dance...

When people think of the word ‘dance’, they probably think of pretty, skinny, and very flexible girls who move to different types of music. Ballet and Contemporary probably being the most boring to watch for some people, simply because the movements are slower and the music isn’t as exciting. Hip-Hop, Jazz, and Tap are most likely appeal to more people because the tempos are faster, and the purpose of the dances is to get the audience more hyped. Dance, however, can be defined in different ways. The ability to dance is defined as leaping, skipping, or hopping with “measured steps and rhythmical movements of the body, usually to the accompaniment of music” [1]. The definition, however, does not explain or describe dance as a medium. It is much more than the leaping, hopping, or skipping. The terms alone do not explain fully what the dancer is doing. Dance as a medium is an imitation of emotion, and is interpreted as, “representing, symbolizing, expressing, or signifying an action, character, emotion- or even its own formal elements.” [2].

Contemporary Dance: The History and Today

Almost every single dancer who started off in beginners ballet when they were toddlers, have heard their dance teacher say that “every dance there is came from ballet.” Ballet is where all technically trained dancers learn well...technique. From the first pirouette, to sauté, and plié, young dancers learn how to both say and execute the proper terms. Around the 1980s, some dancers wanted to branch out of the strict technicality of ballet, and use “unconventional dance styles that were gathered from all dance styles of the world.” [3]. This started a new realm of expressing emotions and finding the limits that humans can move.

youtube

In this video is Martha Graham. She is one of the first to popularize Contemporary Dance and lived from 1894-1991, and her work is compared to that of artists such as Picasso and Stravinski. In this video she, explains the narrative and symbolism behind the choreography and as you watch you can really see where the story pulls through.

As you watch contemporary dance, it is difficult to see a story through the movements if you do not know what to look for. In the earlier days, emotion wasn’t as easy to detect as it was today. Back then it was all about body positioning so you knew what emotion was being conveyed. For example, if a dancer was lower to the floor in their movements, it meant there was a sad or lonely emotion. If the dancer was extended upwards and their arms were in the air, then the dancer was portraying a happy or free feeling. Today, more emotion is expressed on a dancers face, and movements are more unconventional and seemingly random. A dancer now moves naturally to the music. This helps an audience more so now because they need to understand the, “meaning not only produced through narration and the physical communication of emotions...but also through a withholding of movement conventionally considered dance and through experiences thus created,” [4]. Movements in dance today are now closely related to personal experiences, and therefore people can relate to them because of the narrative that they tell.

youtube

In this video, we have a dance from Fox’s TV Show So You Think You Can Dance. We first see the choreographer of the dance explain the narrative of the dance and the roles of the two characters. The narrative, or story, is all about addiction and the people who are addicted to them. In today’s society it is very relative because we live in a world where people have access to drugs and alcohol, which destroys families and causes pain no matter if it is affecting the person doing them or the people surrounding them. Here the male dancer is representing the addiction, and the female dancer is symbolizing the person who is addicted. Their movements are very unconventional and many of them are expressed on the floor. A lot are also with the female being on a lower level than the male, which could represent dominance and power over submission over weakness. Notice, that the fashion expresses the story as well. The female is wearing blood red and torn garments, while the male is very precise and crisp with matching red in parts of his costume as well. Comparably to the first video with Martha Graham, the female dancer is wearing nonrestrictive clothing so she is free to do more movements. This kind of dance, on these TV shows, are known as commercial contemporary dance, in which they are very “emotive, dramatic, and virtuosic,” [5].

Take a Bow

From the way Martha Graham started out with the new movements of contemporary dance, to today with popular shows spreading the different styles of dance, with contemporary being the most popular, “dance has a history which is worthy of study in order to enhance knowledge and understanding of the past and the present,” [6]. Dance is a narrative in which we can infer stories from the both the past and the present.

Notes

[1] [2] Jessica Simon, 2018.

[3] Dance Facts, 2018

[4]Yvonne Hardt, 2011, 39.

[5] SanSan Kwan, 2017, 42.

[6] Alexandra Carter, 2004, 2.

Work Cited

Carter, Alexandra. Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. London; New York: Routledge, 2004. UF Catalog. 18 Feb 2018.

“Contemporary Dance- Ballet Dance.” Dance Facts. Dance Facts. 2018. 18 Feb 2018.

Hardt, Yvonne. “Staging the Ethnographic of Dance History.” Dance Research Journal, 43(1): 27-42.

Kwan, SanSan. “When is Contemporary Dance?” Dance Research Journal, 49(3): 15-38

Simon, Jessica. "Dance.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. WordPress. 2018. 18 Feb 2018.

-LA

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keyword Definition: Narrative/Narrative Poetry

Many people do not recognize narrative as a medium itself. However, the narrative form is frequently used in day to day conversations: such as the retelling of stories, social media, press, etc. This paper will be focusing on the definition of narrative and how it connects to narrative poetry medium. A narrative is a story with a spoken or written account of connected events. It is a description of related events, real or imaginary, presented in a sequence of written or spoken words, still or moving images, or even both. In plain terms, it is basically a form of retelling, using words, of some event that happened, also known as a story. Narrative poetry is a form of writing that mainly focuses on the narrative throughout the entire work.

Narrative poetry is an example of using the narrative within another medium. It connects the narrative writing style in the form of poetry, thus narrative poetry. Narrative poetry is a form of poetry that tells a story, often making the voices of a narrator and characters, and it is also a form of communication. The story is usually written in metered verse and does not always have to follow rhythmic patterns. Poems that make up narrative poetry may be short or long, and the story it relates to may also be complex. Narrative poems typically include epics, ballads, idylls, and lays. Some narratives take the form of a novel in verse, and shorter narrative poems are often similar in style to the short story. Many poems are narratives, but also, many narratives are poems. “Most poems before the nineteenth century, and many since then, have been narrative poems. The range of narrative poetry is enormous; it includes the entire epic tradition, primary and secondary, oral and written, as well as medieval and early-modern verse romances, folk ballads and their literary adaptations, narrative verse autobiographies” (Beginning to Think about Narrative in Poetry, 12). Poems were known to have the narrative aspect in its stories, hence it became a popular form of writing. It became a well-known form of writing and many commonly used it in their poetry. However, many people today do not consider narrative as part of poetry.

Not all poetry is included in the narrative poetry category, but that does not mean that all poetry is not narrative poetry. There are many poems that include the narrative form within their stories and plot. It can be seen that “the majority of the world’s literary narratives are poetic narratives” (McHale, 12). Just because not all of them are centered around the narrative form, it is not acceptable to exclude all of poetry completely. Because of the great complexities of narrative and poetry, narrative poetry deserves to be recognized as its own medium. People underappreciate the value of narrative poetry and what it can teach.

One of the first things that comes to mind when thinking of a narrative is a novel or short story. They have become the focus of narrative stories, and many people start to forget that other forms of poetry also use the narrative in their writings. Hartsock explains that the definition of “narrative literary journalism is true-life stories that read like a novel or short story” (22). He also mentions that reading novels or short stories results in “social or cultural allegory, with potential meanings beyond the literal in the broadest sense of allegory’s meaning” (ibid). Over time, novels and short stories have become more popular today that the numerous other forms of narrative poetry have started to be forgotten.

Narrative poetry can also be used as a teaching tool because poetry can be a powerful medium for literacy and technology development. Narrative poetry is a common type of poetry used today, but it is not widely recognized as popular. Many authors use this form of the narrative, and it is important to consider how common it really is and should be recognized as a beneficial technique in poetry. I think that the definition of narrative poetry has changed over the years based on sociocultural influences. The basis of the poetry remains the same, but like anything it changes over time. A while ago, poetry was only considered for pleasure reading, but now it is used as a teaching tool. Poetry can be seen to have an “important role in improving literacy skills and [there are] a variety of ways to make poetry teaching effective” (Hughes, 1). It has become a useful tool in helping students understand poetry and the English language.

Contemporary narrative theory suggests that narrative poetry is no longer commonly recognized as part of poetry today. Many readers and audiences do not pay attention to the aspect of narrative in the poetry. There is only the focus on ‘poetry’. The narrative continues to be used in numerous mediums, however, poetry is not considered a medium that contains narrative. The contemporary narrative theory is almost silent about poetry, for it seems to neglect poetry entirely. It does not mention or consider poetry when discussing narratives. The narrative aspect of poetry is starting to be forgotten in today’s era.

Another problem with narrativity and poetry is modernism. It is believed that modernism creates a problem with the long poem. According to McHale in “Weak Narrativity: The Case of Avant-Garde Narrative Poetry,” modernism interdicts narrative modes of organization and submits the long-poem genre, for example, to a general lyricization. As a result, this form of the long poem lacks any continuous narrative. Instead, it is made up of lyric fragments strung together in sequence. He continues to discuss that the narrative, while not utterly banished, becomes the invisible "master-narrative" which is not present anywhere in the text but ensures the text's ideological coherence (162). However, in postmodernism there is more narrativity in poems than with modernism, but there is still a difference. McHale continues to argue that it is problematic to identify the narrative in poems. He says that readers have trouble “determining what belongs with what, of reassembling the scattered narrative fragments; and the text refuses to cooperate with us in the task, as it might have done by indicating relevant continuities (coreference) of space, time, or agent from fragment to fragment” (ibid). Even though it may be hard to determine exactly what the narrative is trying to convey, it does not lessen the significance of poetry using the narrative form.

Works Cited

Hartsock, John C. A History of American Literary Journalism: The Emergence of a Modern Narrative Form. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, c2000., 2000.

Hughes, Janette. "Poetry: A powerful medium for literacy and technology development." 2007, file:///C:/Users/crazy/AppData/Local/Temp/Hughes.pdf.

McHale, Brian. "Beginning to Think about Narrative in Poetry." Narrative, vol. 17 no. 1, 2009, pp. 11-27. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/nar.0.0014.

McHale, Brian. “Weak Narrativity: The Case of Avant-Garde Narrative Poetry.” Narrative, vol. 9, no. 2, 2001, pp. 161–167. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20107242.

-KK

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keyword Definition: Memes

Memes

When we look at memes, we don’t really consider much about them aside from their comical content. Memes as popular culture knows them are all over Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Many times, we neglect to acknowledge the cultural significance of memes, and we also fail to see the range of things that are considered to be ‘memes.’ The term ‘meme’ is a kind of umbrella term for ideas and images.

History of the Meme

Richard Dawkins, one of the world’s most prominent evolutionary biologists, first coined the term “meme” to describe the evolution of ideas. Dawkins wrote that memes expand and diffuse, in a broad sense, through imitation. “Uniquely among animals, humans are capable of imitation and so can copy from one another ideas, habits, skills, behaviors, inventions, songs and stories” (Blackmore, 1999). Memes were able to travel wordlessly before the formation of written language. Mimicking the behaviors of others was enough to transmit ideas. This worked for building fires, shaking trees, and carving arrows. For the majority of human history, memes were transmitted by word of mouth. Most recently, they have found themselves expressed on solid substance, such as on clay tablets, cave walls, and sheets of paper. Memes can be fashions, legends, skills, etc. Technology, specifically the Internet and computers, has changed the meme landscape faster than ever before. The Internet is responsible for facilitating the diffusion of ideas, images, catchphrases, etc. and making them more globally accessible than ever. Internet image memes have their own history. The limited scope of these kinds of memes in the early 2010’s has drastically expanded by 2018 to include references to television, videos, Vines, music, celebrities, and even stock images. It is difficult to imagine what there isn’t a meme about. It is understood among mostly millennials that utilize social media that one specific meme maintains its prominence for about a month until a new one is popularized. Examples of these memes would be Salt Bae, Caveman Spongebob, and Surprised White Guy.

Kinds of Memes

Dawkins explained that memes come in different forms. Ideas can arise uniquely or show up several times, or it may dwindle and vanish (Gleick, 2011). For example, the belief in God is an ancient idea that has manifested itself in a smorgasbord of ways, such as animism, polytheism, monotheism, and deism (to name a few). Tunes and catchphrases can diffuse across different cultures, often taking decades or even centuries to spread to the ends of the earth. To exemplify, Confucian principles have traveled all the way from Asia and have grown in popularity along Western society. Images can gain popularity and significance across cultures as well. An incredible example of this would be the Mona Lisa. With the growth and spread of the Internet and related technologies, memes have been created, circulated, and built upon. It is important to note what a meme is not. The number seven is not a meme, nor is the color purple. A balloon on a string is not a meme. Gleick notes, “Memes are complex units, distinct and memorable—units with staying power.” Once a meme penetrates society, it has the potential to gain momentum and spread. In the context of Internet image memes, the process of a meme gaining utmost popularity is called “going viral.” When memes are talked about in casual conversation, it is most likely that they are referring to Internet image memes, which have also grown in sophistication over the past decade.

Meme Meaning Morphing

Today, when a meme is referenced, most people think about a funny picture or video that relates to a scenario. There are countless different internet memes that regularly saturate social media timelines. Milner states, “They’re used to make jokes, argue points, and connect points” (Milner, 2016). Millennials are the ones who primarily utilize memes on social media platforms in a humorous way. A more recent trend in the meme community that has gained momentum is self-deprecation. One of the more popular meme trends has to do with hypothetically engaging in suicidal behaviors to dramatically toy with the idea of dying as a result of one’s circumstances. For example, someone may tweet a statement lamenting the current state of life and post a picture of bleach in a drinking glass to imply that they would drink the deadly chemical to escape the trials of living. Sterelny writes, “… it is fruitful to view cultural evolution through the meme’s eye… human cultural activity is the phenotypic effect of meme lineages expanding through time…” (Sterelny, 2006). By looking at memes and their affect on society, we are able to see how ideas, images, and catchphrases can gradually morph humankind. It is argued by many that the use of memes during the 2016 election had a huge impact on who was chosen as the candidates in the primaries. Painting Bernie Sanders in a certain laidback light lacking seriousness gave Hillary an upper hand in being chosen to represent the Democratic party. On the other hand, memes about Ted Cruz being the Zodiac Killer made him a less serious candidate to the public and lessened his appeal. The spreading of ideas and images has, over thousands of years, moved us into a more “civilized” society. Memes are responsible for the creation of laws and societal structure, and without the transmission of memes, life as we know it today would cease to exist.

Works Cited

Gleick, James. “What Defines a Meme?” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Magazine [Online], May 2011, www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/what-defines-a-meme-1904778/.

Sterelny, Kim. “Memes Revisited.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, vol. 57, no. 1, 2006, pp. 145–165. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3541656.

Milner, Ryan M.. The World Made Meme : Public Conversations and Participatory Media, MIT Press, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ufl/detail.action?docID=4714221.

Blackmore, Susan J. The Meme Machine. Oxford [England: Oxford University Press, 1999. Print.

-CD

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keyword definition argument: Memes

What in the Meme?

In this digital age, memes need no introduction, or so you would think. They are ubiquitous on all platforms such as Twitter, Reddit, Ifunny, Facebook, etc… you name it! These platforms allow memes to be easily distributed among the masses. We are all familiar with them, but how would you define them? Their ambiguity stimulated my curiosity to find out what others had to say.

Memetics

The word meme originated from the Greek mimena, meaning “imitated thing.” Richard Dawkins coined the word meme as an analogous term for gene, meaning cultural unit of transmissible information. But why? Kate Distin’s The Selfish Meme, illustrates Dawkins’ beliefs on how culture evolves and that memes serve as cultural selection (6). In addition, Dawkins proposes that clothes fashion, ideas, or catch-phrases could all be considered cultural units of information or a representation. This is the oldest classification of memes. Memetics, or the study of memes as cultural replicators, is another term coined by Dawkins analogous to genetics. Selection, replication, and variation are key elements in which a meme must undergo to successfully transmit its narrative, thus evolving culture. Distin suggests that “Selection means that some replicators are favoured, survive and propagate” (68). For example, theories that are collectively accepted or trends that are eventually disposed of. Next, Distin examines replication, “the transmission of memetic content will be facilitated by such standard cultural methods such as imitation, teaching, and everyday communication (69). Finally, Distin mentions that “variation, such as mutation and recombination, are subject to certain biases and limitations, determined by what exists and its assembled organization” (70). Not only are memes replicated, but they are also altered depending on who stumbles upon the meme due to their personal agenda. Many disagree with the meme hypothesis, because there is a lack of empirical data governing the evolutionary process of cultural units. However, I believe the theory makes logical sense and the author makes a valid argument highlighting the correlation between cultural and biological evolution.

Freedom of Expression

The internet undoubtedly changed the meme scene. The rise of social media allows us to broadcast memes on a broader scope. Thus, more people are likely to encounter memes, alter, and replicate them. This will go a long way to ensure memetic survival. Numerous applications and sites such as Canva and Meme Generator facilitate the process of constructing memes. Most memes are shared between friends to insight laughter. However, the creator of a meme has the freedom of expression to post anything they want while considering their invisible audience and any copy right infringements. That is, the fact that anyone at any given moment can encounter your meme because of their capacity to go viral on the internet. Although the content used in memes are replicated, one must be weary of using those images without crediting its source. Sean Rintel claims that most common replicated memes in the early 2000's were based on image macros, or a picture with superimposed, bold text. This template is widely used for images that "are usually striking representations of an action or emotion, often taking the form of a human, anthropomorphized animal or object" (Rintel 257). Crisis memes refer to images that offer satirical or macabre content as "responses to challenging events based on thematic and structural templates of popular image macros" (Rintel 266). Memes are generated each second responding to social and political crisis in a humorous way. Crisis memes offer comic relief because we live in a time where it is socially acceptable to mock disastrous situations. Otherwise, people would not constantly expel and share crisis memes with one another.

Popular Culture in the Classroom

Popular culture unifies a myriad of people. Sharing your favorite gifs, or moving images, and viral clips with others develop stronger bonds. Most people will agree that memes are made and shared to evoke laughter, and this could still be accomplished in a classroom setting. Eager and enthusiastic, Ciro Scardina, uses his avid love for popular culture to form a better relationship with his students. He believes that "the meme is a beautiful tool to explain a concept and for students to express their knowledge on a topic and flex their critical-thinking skills" (13). That concept could be anything ranging from a simple math equation to a historical statement. Although there are hardly any articles written about memes in an educational setting, I do agree with this claim because I can recall learning from memes in school. It seems to be a widely-used tactic, yet hardly commented on. My tenth-grade English teacher had memes posted around the classroom. For example, one was centered on the Willy Wonka image macro with the written text: "Oh, I didn't know conversate was a word." The Willy Wonka meme is a sarcastic approach to ridicule the concerning topic, using the word "conversate" instead of converse." For one to understand the meme, they must understand the misuse of converse. My teacher had shown us the meme, and then told us that the misuse of conversate is her biggest pet-peeve, and that instruction was so unique that I will never forget it. As a student, structured text becomes repetitive and boring. On the other hand, memes have become a subtle way to learn. Students utilize their critical thinking skills without noticing. Because of this, memes have become desired teaching tools for students with shorter attention spans. Memes are learning made fun. Scardina also mentions "Popular culture is a reinterpretation of everyday life and experiences, and the meme is the visual symbol of this reinterpretation" (14).

It now seems clear to me what memes are. A meme could be any media sharing a message that gets passed along to others. Memes can go viral and be viewed by anyone in the world thanks to social media. Dawkins introduced memes as songs, art, or ideas that are judged based on how easily they are passed down from person-to-person, evolving culture. This concept seemed to stay intact in all sources of information I gathered. Dawkin's definition is more scientific than most because he based his meme theory from evolution. The internet has made sharing memes an everyday part of life because they are always found on our social media feeds. The main difference between memes before and after the internet is the structured format that came with meme generators. Meme generators have caused memes to look a certain way. For example, image macro with the superimposed text. The structure gives the memes away; people know that the content will be silly or satirical whenever they encounter this structure. Because of this, it is safe to say that memes are considered popular culture. People generate memes pertaining to all kinds of situations, appealing to almost everyone. Sharing memes create a rich bond between people because it creates a sense of familiarity and unity. This could even be accomplished in a school setting because the students will trust that their teachers care about their culture and create a better learning environment because of it.

Works Cited

Distin, Kate. The Selfish Meme. Cambridge University Press, 1827.

Rintel, Sean. "Crisis memes: The importance of templability to Internet culture and freedom of expression," Australian Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 2, no. 2, 2013, pp. 256-261.

Scardina, Ciro. "Through the Lens of Popular Culture," Teacher Librarian, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 13-16.

-MB

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Problem With Music

Music, like art, is often a term governed by intuition rather than reason. However, philosophers have been struggling to come up with a definition for music; one subset of questions seeks to define what music is after it is objectified for study, while other lines of intrigue delve further into the necessary and sufficient conditions required to call something “music.” Questions of the former category might ask: does music lie in the performance? Is music the tangible artifact on which notes are written? Or, does music exist independent of both the physical and performative aspects associated with the concept? For the purpose of this definition, however, we will assume that music is the aural phenomenon we observe during a performance of some fashion.

Additionally, this definition will primarily focus on “pure” music- music without accompanying words or lyrics- as opposed to what we might refer to as a “song.” Andrew Kania argues that this distinction and limitation is important, because “the solutions are likely to be more easily evaluated” (Kania, 3). This is the case because pure music seemingly presents the most complex problem to philosophers and scholars alike; music without linguistic context is much more challenging to understand than its lyric-endowed counterparts. Indeed, if we can explain the phenomenological aspects of music in its pure state, it stands to reason that we can therefore explain and define music in its impure state.

Kania begins his essay explaining that music is most often defined as “organized sound,” but this is not a particularly useful definition as it is oversimplified and overly vague (Kania 4). Typically, philosophers attempt to define things in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. For example, in order to be a bachelor, it is necessary to be a man. This, however, is not sufficient because one must also be unmarried in addition to being a man. Philosophic inquiry into music has two primary necessary conditions: tonality and aesthetic properties. However, Kania thinks that these conditions are merely striking aspects “of an unavoidably vague phenomenon,” that struggle to refute many obvious counterexamples (Kania 5). Indeed, those who endorse the tonality condition have trouble defending their position from examples of non-tonal percussion instruments like the snare and bass drum. These instruments make music in an acutely classical sense of the word, yet they fail to meet to tonality condition. As for those who assert the necessity of the aesthetic, poetry is the most common counterexample. It possesses aesthetic qualities often communicated via sound, yet poetry is not considered to be music.

Some philosophers are also concerned with how music is able to evoke certain images, impressions, words, or emotions without any textual accompaniment and whether or not the answer will have any bearing on the actual definition of music. Many turn to semantic theory in order to better understand how aesthetic properties are at play within pieces of music. In her essay titled Music as a Representational Art, Jenefer Robinson claims that meaning is placed in music “when [composers] affix a program to a piece of descriptive music” (Robinson 180). Consequently, music is able to evoke certain emotions or communicate ideas because of a textual item which precludes the performance of said composition. However, this still does not answer why we may feel sadness or joy when listening to a piece of music without first reading a title, but Robinson asserts that music “generally sounds more like other music than what it supposedly depicts” (Robinson 178). This helps explain why we are able to recognize when a particular composition is melancholic or when another is happy. For example, it would make no sense to cry during a performance of Grainger’s Country Gardens considering its upbeat tempo and major key. Indeed, we use prior musical experience as a reference point and build a library of knowledge to decipher what we hear and how we should react to this music. Musical understanding, like spoken language, often relies on external references to help guide in the conditioning required to intuitively grasp what sad music sounds like as opposed to happy music. As a result, different interpretation and conditioning is often nonexistent within the microcosm- this is to say that, within a given culture, fundamental understandings about music rarely differ. For example, most, if not all, would say that a minor chord is “sad” while a major chord is “happy.” However, Irving Godt argues that “different cultures have different ideas about music” (Godt 83). This notion of cultural relativity holds that our definition of music may not exactly be the case in other cultures where quarter-tones and the like exist regularly within the music. Consequently, the purpose of this definition is to primarily describe Western Music.

Some scholars form more complex definitions in an attempt to incorporate aspects of both aesthetic properties and tonality; below, I have included Godt’s definition to serve as a reference- it is as follows:

“Unwanted sound is noise. Music is humanly organized sound, organized with intent into a recognizable aesthetic entity as a musical communication directed from a maker to a known or unforeseen listener, publicly through the medium of a performer, or privately through performer as listener. As far as I know, ethnologists have never found a human society that does not make music.” (Godt 84)

In the above definition, the canonical “music as organized sound” claim is clearly made and narrowed down in an effort to exclude natural/background noise. Other notable features that are relevant to this definition include an emphasis on intent, aesthetic properties, and musical communication. In many definitions of art, intent is necessary in order the establish that animals like chimpanzees do not create, at least in the paradigmatic sense, art. Which is to say that art is a uniquely human phenomenon, and therefore, it makes little sense to extend works of art to other species that are not capable of realizing art. “Musical communication” refers to the condition of tonality, and as we can see, Godt’s description still falls prey to easily conjured counterexamples such as common percussive instruments.

However, Godt’s definition does little to clarify what is meant by a “recognizable aesthetic entity.” Does this mean that music can only be classified as such if it shares similar aesthetic characteristics to music? Others, like Monroe Beardsley, contend that defining a word such as music is “not at all to ‘legislate’ what creative artists shall do” (Beardsley 177). Even still, the avant-garde will continue to push the boundaries of what is considered music; this is a common trend across many disciplines of art. John Cage’s 4’33 is a commonly cited composition that pushes the boundaries of what is to be considered music, and so it seems as if younger generations are driven by impetus to create what they will invariably call “music” even as it flies in the face of all existing definitions of the term. In turn, what we intuitively know to be music now may not be the same in 20 years.

Works Cited:

Alperson, Philip. What Is Music?: an Introduction to the Philosophy of Music. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

Beardsley, Monroe C. “The Definitions of the Arts.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 20, no. 2, 1961, pp. 175–187. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/427466.

Godt, Irving. “Music: A Practical Definition.” The Musical Times, vol. 146, no. 1890, 2005, pp. 83–88. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30044071.

Kania, Andrew. “The Philosophy of Music.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 11 July 2017, plato.stanford.edu/entries/music/.

-JM

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video Essay

Anyone who has spent a decent amount of time on the internet is probably familiar with the concept of the video essay. The University of Notre Dame’s ReMix-T defines video essays as “written essays that are read aloud and mixed with a stream of images, sound, or video.” The video essay has definitely received more traction in the past decade; however, although many scholars consider it a new form, the video essay has, as scholar Andrew McWhirter puts it, a “distinctive prehistory that lies beyond contemporary moving-image culture and deserves particular consideration.” (369) I always thought the video essay was a recent argumentative form; however, upon closer research, I have discovered that the concept of the video essay has been built around its lesser-known predecessor, the essay film. It is important to clarify that the essay film is still around today; yet, a comparison and understanding of the history of these two terms gives a greater context for how the video essay has come to be.

Essay Film: The Precursor

youtube

Before the video essay ever became a common form of argument, filmmakers and essayists alike were creating essay films. Unfortunately, the history of the essay film is not so easily understood; it is not entirely known where or when this form of essay popped up. According to an article from Dazed, the essay film emerged “not long after the Lumiere Brothers recorded the first ever motion pictures of Lyonnaise factory workers in 1894.” (Yeung) However, essayist and film critic John Bresland claims that Chris Marker’s 1982 film Sans Soleil and 1955 film Night and Fog (trailer shown above), are some of “the first great film essays of our time,” (181) implying that he either does not agree with Yeung, or does not believe the essay film formed its identity until the latter half of the twentieth century. What may have lead to this discrepancy is the fact that the essay film is as difficult, if not more so, to define as the video essay. Phillip Lopate, in his 1992 essay for The Three Penny Review, describes the essay film as a centaur: half film, and half essay – two different animals combined as one. The essay film, as McWhirter describes it, is “a detailed continuum between two different registers: the explanatory, which is analytical and language-based, and the poetic, which is expressive and battles against language with a collage of images and sounds.” (371) These two registers are so diverse and distinct in and of themselves that it is difficult to pinpoint exactly what elements make an essay film different from a documentary or a narrative film, both of which the form takes from.

Compared to other genres and forms of film, the essay film never became a substantially popular genre; while it certainly had and still has an identity, Lopate calls it a “cinematic genre that never existed.” (19) Why did it never fully take off? Lopate gives a couple of reasons for this. The first is that there are commercial consequences that need to be taken into account; just as essays “rarely sell in bookstores, so essay films are expected to have little popularity.” (22) In the film-making sphere of the western world, the narrative film became the prominent genre of film; a majority of scholarship was dedicated to examining the narrative film, leaving forms like the essay film to be left in the avant-garde or indie category. Lopate also claims that essayists and writers may not be too familiar with film and directing, and filmmakers may not be too familiar with crafting essays. In the twentieth century, film-making was not accessible to everyone; it required the right equipment, the right people, and the right amount of money. Ultimately, creating and consuming essay films was nothing short of an ordeal. However, Lopate would have never realized that this concept of a centaur would flourish in the twenty-first century.

Part Two: The Rise of the Video Essay

youtube

If there is one word to describe the advent of the video essay, it would be ‘Digitization.” Technological advances have permeated nearly every facet of our lives, and the way we communicate, share ideas, make and interpret art, and access information have completely changed. It is this transformation that has allowed the video essay to form from the essay film. The rise of the Internet has given video essays a way to shine, and solves the issues that Lopate notes for the essay film back in the nineties.

The video essay, like the essay film, is comprised of language, images, and audio; and just as the unobjective and singular voice of the director / writer is so important in the essay film, it plays a major role in many video essays. Yet, despite these similarities, the digital age has allowed the video essay to excel as a form; searching for “video essay” in the YouTube search bar brings up over 2.5 million results. How did this happen?

One of the biggest changes to the form of the visual essay is the apparatus that records the visuals and audio. Film requires a shutter to convey motion; it is mostly viewed in dark movie theatres, and Bresland argues that it is “this nocturnal portion that stays with us, that fixes our memory of a film in a different way than the same film seen on television or on a monitor.” (183) Video, on the other hand, is digital; our culture experiences video in a very different way than film. We capture video with “small, light digital cameras,” and consume it on “mobile devices, on planes, as shared links crossing the ether.” (Lopate 184) Going to see a film required effort and money; now, anyone can access just about anything at little to no price.

This not only changes who consumes the visual essay, but who creates the visual essay. As mentioned before, making an essay film requires a lot of money and a lot of manpower. All it takes for someone to create a visual essay now is a camera, a free editing program, and a YouTube account; anyone can “shoot an edit video, compelling video, on a cellphone camera.” (183) The essay film may not be as effective for, or even advertised to, the mainstream movie audience; now, this general audience can now be a part of the academic conversation by watching these video essays wherever they go. It is also important to note that this shift in audience also changes how the essay is written. A majority of video essays are written in colloquial language rather than scholarly language, so that anyone, regardless of their academic background, can understand the argument. Lindsay Ellis’ video about Stranger Things and It, shown above, is a good example of how the video essay is approached very differently. This also explains why many video essays are short in length, whereas many well-known essay films are the length of a feature film.

Furthermore, this access to the internet has changed how we present our ideas in a video essay. Until the creation of VHS tapes, there was no way to really “own” a film; a scholar would not have access to movie scenes and clips the way we do. This access has led to many video essays utilizing clips for examples and synthesis; this has become so convenient and commonplace in modern video essays that McWhirter iterates that, “while the essay film might take anything as its subject, the video essay itself only has the subject of film at its center.” (371) As the form evolves and gains popularity, this focus on film could definitely change.

Ultimately, the essay film and the video essay are two very different forms, with very different audiences and formation of content. However, as the video essay gains in popularity, it is crucial to understand the prehistory of the term, and how changes in technology and society impact the success and structure of the form. I had never even heard of the essay film before writing this; yet, I believe it is important to have an understanding of the form, as it definitely provides context to how current video essays both differ and coincide with its precursor. And as the boundaries of the video essay continue to be explored, it has never been more important to be familiar with its roots.

- CR

Works Cited

Bresland, John. “On the Origin of the Video Essay.” Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time, edited by Carl H. Klaus and Ned Stuckey-French, University of Iowa Press, 2012, pp. 180-184.

Lopate, Phillip. “9. In Search of The Centaur: The Essay-Film (1992).” Essays on the Essay Film, vol. 48, 2017, pp. 19–22.

Mcwhirter, Andrew. “Film Criticism, Film Scholarship and the Video Essay.” Screen, vol. 56, no. 3, 2015, pp. 369–377

“Video Essay.” Remix-T, University of Notre Dame Kaneb Center, learning.nd.edu/remix/projects/VideoEssay.html.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evolution of the term “Cinema” with the advancing Film medium

The birth of film has not been able to be traced to a specific date or person but the coming about of film is most notably known as being in 1895 when short films were publicly screened in Paris, France. The early 1900’s brought about new film techniques such as lighting and cinematic effects that were able to be added to a film on one reel in order to enhance the simplicity of viewing for the audience. The year of 1927 brought about the advancement of films with sound which changed the whole creative process of filmmaking. Film and cinema were terms that started to be used interchangeably in the United States during the early 20th century but this was not the case in other countries such as France, who’s film medium experts clearly stated that cinema and film were not to be used interchangeably. The birth of the digital world sparked a lot of controversy over the term cinema and whether or not we should be considering cinema and film as one in the same.

The term cinema has many different meanings associated with it. The medium that consists of movies can presently best be defined by the term film, but it has also been called cinema. At one point the term film was associated with movies that were geared more towards an artsy crowd interested in the technical side of creating a movie and people who are more interested in movies that tend to be found in the independent category. Cinema was used to define the movies that were being created for mainstream movie theatres and people who were more interested in the entertainment side of a movie rather than the technical side; These are the movies that are made for the box office profits. Stephen Prince, in his article, “The Emergence of Filmic Artifacts: Cinema and Cinematography in the Digital Era,” talks about how for the hundred years of cinema’s existence it was considered a “photo-mechanical” medium. This meant that the images that were incorporated in a movie were able to come to life by using a darkroom and a film processing lab, “fixed in analog form on a celluloid surface, and then trucked around the country for exhibition” (Prince, 25).

The birth of a digital world changed this definition tremendously. Cinema now incorporates the digital technologies associated with the creation of a movie. These advances include cinematography, editing, creation and incorporation of sound, postproduction, and how the product is showcased. The first feature film to be produced digitally was Windhorse, which was shot in Tibet and Nepal in 1996. After this film was produced digitally, George Lucas produced Star Wars: Episode 1-The Phantom Menace, which was the first film that incorporated footage that was captured using high-definition digital cameras. The change and advancement of film in a digital age has changed all the processes in which film is edited in terms of color correction. “In regard to color timing and the control of many other image variables, digital methods now offer filmmakers greatly enhanced artistic powers compared with traditional photo-mechanical methods” (Prince, 27).

The digital advancement has played a large role in how special effects are used in films and how these special effects affect how the viewer perceives the images they are seeing that were created with such effects. “[…] But it seems likely that the viewer who encounters special effects, with their fantastic, digitalized creatures, is led to frame the image, to contextualize it cognitively, in different terms than images that appear more naturalistic” (Prince, 28). Then digital tools available in regards to digital grading are so advanced that film grading simply can’t keep up and is not able to compete with digital grading. With digital grading, filmmakers are able to import their filmic creations into programs such as Adobe Premiere Pro, After-Effects, Photoshop, etc. in order to edit their images and take advantage of digital postproduction. “Digital-imaging methods […] usage is reconfiguring the process of film production, how things get done, when, and by whom” (Prince, 30). These changes are instrumental to the film industry and the professional cinematic environment.

In the book, “Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film,” written by, Richard Barsam and Dave Monahan, they talk about the differences between film, video, and digital technologies. They state that even though there has been an advancement in video and digital technology, film remains the dominant form (Barsam and Monahan, 462). Their argument is that the phasing out of film stock is not due to its inability to perform but rather because of its high expense and difficulty to edit in postproduction. Because of this, digital technology is becoming the definition of the film medium and a core aspect of the cinema definition. The replacement of digital technology has taken away film’s past definition as an analog medium that “stores images on a roll of negative film stock” (462). With film, as in film stock, becoming a less viable way of creation, the definition of film has become hazy and ambiguous. When you take away the film stock definition of film, film is able to be used in place of cinema which results in an adaptation of the definition of cinema.

In Peter Kiwitt’s article, “What is Cinema in a Digital Age? Divergent Definitions from a Production Perspective,” he addresses why there is no simple definition that can be arrived at when trying to define what cinema is. “Studies perspectives tend to emphasize looking back from reception for meaning rather than forward from conception toward making, and so their language, interests, and conclusions can be different from those of production perspectives” (Kewitt, 4). There has been much controversy over what the true definition of cinema is. Even the dictionary gives cinema a very broad and rather vague definition. The Oxford English Dictionary gives cinema a definition as, “films collectively, esp. considered as an art-form; the production of such films.” The definition of cinema has been assessed by many expects in the varying fields involved in the film medium. What appears to be a main factor in the constant changing or rather, adaptive, definition of cinema has to do with the significant image digital adoption and advancement has had on the medium. While experts such as Stephen Prince proclaim that the film medium in transforming radically, he also claims that at the end of the day, movies will continue to tell stories whether they use celluloid or digital video. “From sound to color to widescreen to digital, with evolutions from “MTV editing” to the photorealistic performance capture of Avatar(2009), innovation after innovation, at its core, cinema remains cinema” (Kewitt, 6). By defining cinema only by theatrical exhibition or technology of film, we leave out important aspects of the film medium and cinematic aspects that help mold the very existence of cinema. This disconnect has always been apparent according to Kewitt but with the advancement of digital technology, the disconnect is even more apparent because there are even more aspects of film and cinema to be interpreted than there was when film generally was seen as referring to film stock or art.

Works Cited

Barsam, Richard Meran., and Dave Monahan. Looking at Movies: an Introduction to Film. W.W. Norton & Co., 2010.

Kiwitt. “What Is Cinema in a Digital Age?Divergent Definitions from a Production Perspective.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 64, no. 4, 2012, p. 3., doi:10.5406/jfilmvideo.64.4.0003.

Prince, Stephen. “The Emergence of Filmic Artifacts: Cinema and Cinematography in the Digital Era.” Film Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 3, 2004, pp. 24–33., doi:10.1525/fq.2004.57.3.24.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keyword Definition: Haiku

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a haiku as, “: an unrhymed verse form of Japanese origin having three lines containing usually five, seven, and five syllables respectively; also : a poem in this form usually having a seasonal reference — compare” (Merriam-Webster). Haikus have long been recognized as a medium for persuasive and descriptive communication. This form of poetry’s origins trace back to Japanese culture, however over time, it has become an internationally utilized medium whose definition has been transformed over time and across cultures. While Haikus have remained a medium for argumentation and storytelling, what defines it has transformed in terms of meaning, purpose and overall structure.

In its original context, Japanese haikus had very specific guidelines. “Traditional haiku uses concrete images to convey an experience or sensory perception typically taking place in one of the four seasons” (Welch 54). In it’s transformation into an international medium, modern day form has stripped the haiku of its need and requirement for a specific type of content. While a subject regarding nature and one of the four seasons was a staple for a traditional Japanese haiku, it is merely an unrequired possibility for current day work. With regard to English haikus, for example, the medium is still inspired by its origins being that, “since there is no real tradition for English Haiku, it must borrow from its Japanese origins” (Kiuchi). However, on the other hand, there is still a full transformation made between traditional Japanese haiku, and the new-age English Haikus. “English haiku poets tend to vacillate between reliance on the Japanese tradition when it serves their purposes and rejection of the same tradition when it does not” (Kiuchi).