#igor strelkov

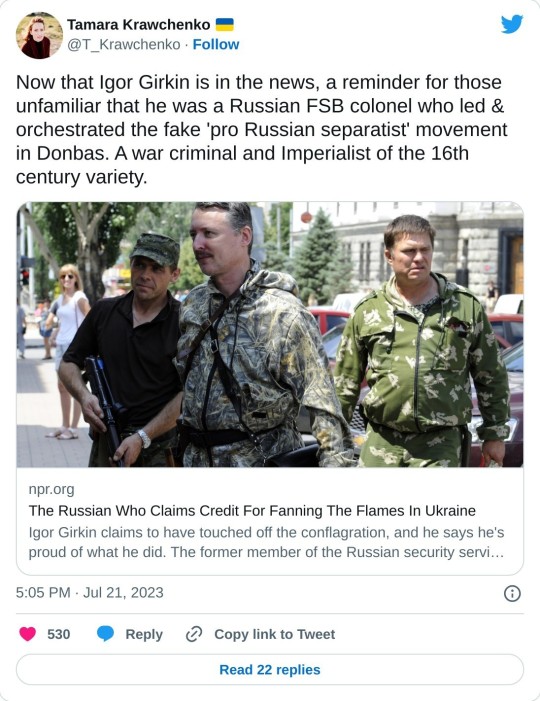

Text

If you shoot down a packed Malaysian airliner over Ukraine, you get praised. If you insult Putin, you're sent to prison. That's life in a hegemonic dictatorship which is Russia these days.

The last time I saw Igor Girkin was five years ago in the stairwell of a Moscow news agency.

"Would you consider giving me an interview?" I asked. "No," he replied sharply and scurried away.

I saw him again today. No stairwell. This time, Girkin was in a caged dock surrounded by police in the Moscow City Court.

Along with other media we were allowed in to film him for just one minute before the end of his trial.

A police dog kept barking. Girkin found that amusing. The verdict less so. Minutes later he was found guilty on extremism charges and sentenced to four years in a penal colony.

This wasn't his first conviction.

In The Hague in 2022, in absentia, Girkin was found guilty of the murder of 298 people: the passengers and crew of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17.

The Boeing jet had been shot down over eastern Ukraine in 2014 by Russian-controlled forces in the early stages of Russia's war there.

Girkin was one of three men sentenced to life imprisonment. A judgement he ignored.

[ ... ]

Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, ultranationalist Girkin became a prominent pro-war blogger.

He became increasingly critical of the way the Russian authorities were waging the war: not hard enough, in his view.

He founded a hard line nationalist movement called The Club of Angry Patriots.

His problems began when he started to take that anger out on President Vladimir Putin.

Public criticisms of the Russian president turned to insults. In a post last year, Girkin described Putin as "a non-entity" and "a cowardly waste of space".

A few days later he was arrested. Now he's been tried and convicted.

Four years is a rather light sentence for dissent in Putin's Russia. Journalists Vladimir Kara-Murza was recently sentenced to 25 years and Ruslan Ushakov is serving 8 years – just to name two.

#invasion of ukraine#russia#ultranationalists#igor girkin#igor strelkov#war criminal#flight mh17#donetsk#vladimir putin#insulting putin#россия#игорь гиркин#игорь стрелков#военные преступления#владимир путин#путин хуйло#путлер#путин – это лжедмитрий iv а не пётр великий#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#руки прочь от украины!#геть з україни#вторгнення оркостану в україну#деокупація#слава україні!#героям слава!#stand with ukraine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#igor strelkov#ex DNR Defense Minister#malaysian boeing#the hague district court#far right extremist#holocaust denier#russian agent#war criminal#ukraine resistance#stop russian invasion#putin war criminal#stop putin#ukraine war#help ukraine#give weapons to ukraine#i stand with ukraine#slava ukraini#donbas

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

100.000 $ recompensă pentru capturarea ”Măcelarului din Slaviansk”. Cine este colonelul FSB în retragere Igor Girkin, acuzat și de implicare în doborârea Boeingului Malaysia Airlines MH 17 în 2014

100.000 $ recompensă pentru capturarea ”Măcelarului din Slaviansk”. Cine este colonelul FSB în retragere Igor Girkin, acuzat și de implicare în doborârea Boeingului Malaysia Airlines MH 17 în 2014

Direcția principală de informații a Ministerului Apărării al Ucrainei a anunțat o recompensă de 100.000 de dolari pentru capturarea lui Igor Girkin, colonel FSB în retragere, unul dintre foștii lideri ai Republicii Separatiste Donețk, acuzat de implicare – alături de alte trei persoane – în doborârea Boeingului Malaysia Airlines MH 17, în anul 2014.

Igor Girkin – alias Igor ”Strelkov”…

View On WordPress

#anexare peninsula Crimeea#Cristian Lisandru#fsb#Igor Girkin#igor strelkov#kremlin#Malaysia Airlines MH 17#proces zbor mh 17#Vladimir Putin#zborul mh 17

0 notes

Text

Le epurazioni di Putin: in carcere il nazionalista Igor Girkin, conosciuto come "Strelkov"

Un tempo fedelissimo di Putin, "Strelkov", vero nome Igor Girkin, ebbe un ruolo chiave nell'annessione russa della Crimea nel 2014. Ma ora è caduto in disgrazia. L'arresto è stato confermato dalla moglie Myroslava Reginska. Secondo l'intelligence ucraina, sarebbe responsabile di torture e omicidi

0 notes

Text

Be Careful What You Wish For

Be Careful What You Wish For

“An Alt-future map where Russia is divided. Could be Post-WW3 or after collapse due to economic sanctions etc.” Source: Reddit

Re: the “volunteer battalions.” Many people, including me, have spoken out quite harshly here [on Facebook] about the irresponsible fools who have posted map[s] of a “collapsed Russia” on the web. The centripetal forces in the country will be more powerful than the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Russian war criminal Igor “Strelkov” (Shooter) Girkin is wanted by many courts. Unfortunately for him, one of them is in his own country. The former soldier, sentenced in absentia in 2022 in The Hague for his role in the MH17 catastrophe, was arrested Friday in Moscow for the 2nd paragraph, article 280 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation “public calls to carry out extremist activities” due to statements he’s made in his recent role as a nationalist provocateur.

Out of all the things Girkin could be plausibly charged for—and there are many—this is perhaps the emptiest possible. Under the Putin regime’s definition of “extremism,” anyone in modern Russia could be guilty, and quite probably it was chosen because it’s the easiest one to pin on him. Criticism of the government used to be relatively safe, as long as you did it from the right—but Wagner Group boss Yevgeny Prigozhin’s failed coup has changed the Kremlin’s attitude. It’s no longer content to just go after the so-called liberal opposition like the imprisoned Alexei Navalny and Vladimir Kara-Murza: A lot of heads are now on the chopping block.

I have a personal enmity toward Girkin, mixed with a weird respect. Because of my work as a journalist and my podcast about the attitudes in the Baltics concerning Russian aggression, his friends have harassed me, threatened me, and even tried to fabricate a criminal case against me in Russia. Yet, at the same time, his military analysis has been eerily accurate. Girkin has called out Russia’s failure to fully mobilize or make full use of its manpower. He criticized the long siege of Mariupol, saying that it would be harmful in the long run by preventing strategic advances while Russia still had the initiative, and he opposed the “meatgrinder” tactics that threw men against hardened Ukrainian defenses. If the Kremlin was capable of listening to criticism like his, Ukraine would be in a far worse position than it is today.

Girkin’s career, and his crimes on Moscow’s behalf, makes him an unlikely figure to end up on the wrong side of the state. But his own strategic talent, and his ability to call out the military disasters of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war, got him there regardless.

Girkin was born on Dec. 17, 1970, in Moscow. Both of his grandfathers fought for the Soviet Union during World War II; however, likely due to his later career in the Federal Security Service (FSB), almost nothing is known about his parents. His passion for military affairs led him to pursue studies at the Moscow State Institute for History and Archives.

Girkin joined the Russian Armed Forces shortly after the Cold War, straight on the path of becoming an officer—because his university course had included military training in the ‘war department’, a part of almost every higher education institution in the Soviet Union and which still exist in modern Russia, he held the military rank of lieutenant right from the start. He served in the 2nd Guards Tamanskaya Motorized Rifle Division, an elite unit notable for its World War II service, helping to overthrow secret police chief Lavrentiy Beria, and taking part in the 1991 August coup against Gorbachev.

While serving there, he developed a profound, albeit somewhat misguided, admiration for the Soviet military heritage. Yet at the same time, in the early 1990s, he also became an enthusiast of the Russian monarchy, whose last members were murdered by the Soviets. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Girkin found himself navigating a changing political landscape. He transitioned to the newly formed Russian Armed Forces and, in the subsequent years, fought in various conflicts, most notably during the Transnistrian conflict (March-July 1992), First Chechen War (1994-1996), and the Second Chechen War (1999-2000).

Girkin’s military acumen and unwavering loyalty to the Russian cause earned him recognition and promotions within the ranks. That’s particularly remarkable in context: Slacking off and nepotism were the norm at the time, and actually putting in some effort was seen as showing off and viewed with disdain. As he specialized in intelligence work and was genuinely competent, he was noticed by the FSB, which often recruits from the military.

By the early 2000s, he had risen to the rank of colonel in the FSB, the successor to the KGB. Throughout his tenure, he was involved in covert and intelligence operations, contributing to his reputation as a formidable figure in the intelligence community inside Russia. At about the same time, he started to appear as a public figure in the Russian-speaking part of the web, criticizing what he called the liberal wing of the government, such as the head of the Russian Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina, and various other figures that he thinks are serving Western interests, calling for a patriotic shift in the government, toward what Strelkov calls true Russian values.

All that prepared him for the dirty tricks needed for Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014. He’s proud of it, too, and his pro-war friends take pride in what he did. Girkin was the commander of the so-called separatist forces in the Donbas back in 2014, which, in truth, were Russian-funded and -supported mercenaries sent to Ukraine to cause trouble and facilitate conflict—a fact that he’s admitted himself. First, in April 2014, he appeared in Sloviansk, a city in eastern Ukraine, while in command of the supposed separatist forces—Putin’s infamous “little green men.” And after that from May 16, 2014, until Aug. 14 he also formally served as the minister of defense of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic.

His role mixed military action and public propaganda aimed both at Russians and the outside world. Girkin became a leading proponent of the “Russian Spring” movement, advocating for the secession of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions from Ukraine and their integration into the Russian Federation. One of his jobs was to make it appear as if the movement had sprung up naturally, when, in fact, it was a wholly Russian government-funded affair. And he did his work diligently.

He forced the Crimean parliament, at gunpoint—literally, he was physically present in the room when this happened—to hold the independence referendum that caused Russia to annex the peninsula and served as the first minister of defense of these “people’s republics” in Donetsk that would later form into Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic, when actively leading their forces into battle against the Ukrainian military. This led to the MH17 incident, where he gave a direct order to fire upon the passenger plane that was flying over Ukrainian territory at the time, via a Russian-provided Buk surface-to-air missile system. Troops under his command followed through, the plane was shot down, and 298 people were killed. He had publicly stated that “We did warn you — do not fly in our sky,” had misidentified it as a Ukrainian transport plane, and boasted about it on his social media channels afterward—of course, those posts were soon deleted, and he’s been denying his involvement ever since, claiming innocence and that it was a Western provocation, using Ukraine as a proxy for it.

In his personal politics, Girkin is a Russian monarchist and an irredentist. He despises the West and lives under constant delusions of grandeur. He’s stated in interviews and on his social media that the United States is “planning to destroy the entire Russian Federation,” and in many of his videos that he publishes on his Brighteon account he mentions “respectable Western partners” mockingly, making claims about how homosexuality is enforced in the West and that if Russia loses this war, then it won’t have traditional family structures anymore, only ‘parent one’ and ‘parent two’ as he claims is true in the U.S.

All that was a good match for the triumphalist mood in Russia following the relatively easy and painless conquest of Crimea. But Girkin’s reputation, despite his initial successes in eastern Ukraine, suffered during his tenure as a separatist leader thanks to allegations of human rights abuses and military miscalculation – the latter being attributed to him by the pro-Putin Russian war supporters. He failed to win the fight for hearts and minds, and instead of being viewed as a liberator, as he wants to see himself, many of the people of the regions he occupied consider him to be nothing more than someone who contributed to their ongoing misery.

Of course, the feelings are mutual. He personally hates Ukrainians and also the Dutch. Ukrainians, he argues on both his Brighteon videos and his Telegram channel, are all actually Russians that have been “tricked by the West” to think they have their own language and culture, and the Dutch he hates because they had the audacity to rebel against their Habsburg monarch, their “rightful king,” and desired their own rights and liberties. Girkin also despises the United States and everything it stands for, believing that the U.S. is responsible for everything awful that has ever happened to Russia. Since he doesn’t speak or understand English, he gets his info by reading news articles from far-right sources in the West, created by authors that would make Alex Jones look sane, using Google translate or being told about them by his fellow angry patriots, especially by the self-proclaimed futurologist of the club, Maxim Kalashnikov, who acts as the expert on all matters relating to western politics in their club.

By late August 2014, Girkin had left Ukraine—but he didn’t stay uninvolved. His primary platform has been his Telegram channel with 868,992 subscribers where he lays out his ideas and publishes his videos, which are uploaded primarily on Brighteon. Occasionally, he uses VKontakte (a Russian equivalent to Facebook) as well as radical Russian YouTube channels, such as Roi TV (Wasp TV). He has been invited as an “expert” onto many of the far-right Russian YouTube and Telegram channels for interviews. His audience mostly consists of people who are Russian nationalists or are nostalgic for the loss of the Soviet Union or the Russian Empire—or both. They are united by the fact that they see the corruption in modern Russia and Putin’s incompetence and believe that somehow this is caused by the ruling elite actually being in league with the West and only caring about enriching themselves.

This is also the focus of his political movement that was officially created earlier this year—this “Club of Angry Patriots,” which, supposedly, will unite what they refer to as the progressive and healthy forces of Russia, with their goal being the utter destruction of Ukraine, both as a nation and as an ethnic identity, “winning” over the West, and building what they consider to be the best possible Russia.

Their vision, as can be summarized together from all their various disjointed statements and beliefs, is of a police state even worse than the one run by Putin, where effectively neo-Nazis in the form of national Bolsheviks would reign freely and share absolute rule with monarchists, radical communists, and every other marginal radical extremist in Russia under a single banner. They also believe that Russian people would honestly elect such people in fair, open elections. Of course, most of them are also rampant antisemites, but that doesn’t stop them from calling themselves antifascists as well.

And yet while Girkin’s politics are evil, his strategic acumen is strong. As a veteran, he knows military matters quite well. Girkin’s a great source for Western observers of the war because of this—he doesn’t spew nonsense and outright lies about HIMARS systems being destroyed, or downed Storm Shadow missiles or constant military victories like Russian Ministry of Defense spokesperson Igor Konashenkov—if you add up all of the statements made by Konashenkov over the duration of the conflict, then Russia claims to have destroyed more HIMARS than were ever delivered to Ukraine. In reality, they have not managed to destroy any of these weapons systems.

Girkin admits defeats and is objective about Russian prospects. He’s called out the Kremlin on the need of the Russian army to provide proper training and equipment for its conscripts, the shortage of manpower, the lack of drones and modern communications equipment, and, of course, the constant, massive corruption that plagues the Russian military.

But the problem is that, at this point, the only man Girkin hates more than Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is Putin. He’s hated him since 2014, after he was forced to retreat from eastern Ukraine and leave Donbas. Girkin felt betrayed by the Kremlin, believing that his idea of “Novorossiya” would have come true if he had had more support. Because of this, Girkin thinks that Putin is a weak leader and wholly incompetent. He’s become more and more aggressive about this lately. In the Telegram posts linked above, he mixes nationalism with misogyny. In those he says: “Miserable whining, complaints about partners, appeals ‘for all good against all bad’—that’s there as much as you want. But for a very, very long time now, the president’s rhetoric does not even remotely resemble the traditional ‘masculine standard’ and ‘In general, concluding my reflections, I have to regret that Putin is not a woman. A weak-in-character and not very smart woman could have had talented favorites. […] It also depends on luck, actually (often quite the opposite has happened), but there would have been at least a chance.”

While he argues that Putin should not be removed from power, as that would lead to a complete collapse of Russia, he thinks that “Russia won’t take six more years of this idiot being in power.”

For a long time, Girkin was able to get away with these kinds of comments because the security state didn’t go after the far right. For all his noise, too, he wasn’t a successful figure; he frequently complained of being broke and seems to have genuinely struggled to get by. He has even boasted about it, saying that he’s more honest than the people in the Russian administration, as he’s poor and that it shows he hasn’t been stealing from the Russian people, as Putin’s oligarch friends have been doing.

But today, Girkin’s not the only figure on the Russian right to be targeted. Recently, an administrative case was started against Vladimir Kvachkov, a close (and extremely antisemitic and overall insane) associate of Girkin’s, and during the protest against Girkin’s arrest—to which a whole two dozen people arrived—the formal head of this Club of Angry Patriots, Pavel Gubarev, was also detained. Finally, the ax has fallen even on the pro-war pundits who make the mistake of criticizing the powerful.

Part of the reason for this is Prigozhin’s revolt—after the sudden events in late June, Putin’s become much more paranoid. At this point, any criticism, no matter how genuine and constructive, is seen as a precursor to some other coup or rebellion, and any disagreement is seen as a direct threat—up to the point of firing generals who are viewed as competent by their men just because they spoke up about their difficult situation on the front. Currently, Putin values only absolute loyalty and sycophancy.

But another reason is the nature of the security state itself. Russia is out of liberal opposition. Putin jailed, killed, or forced into exile anyone and everyone who tried to oppose him. But, as in the Soviet era, the siloviki (enforcers) need to be paid for something—and if there aren’t any student protesters to be beaten up in Red Square, that means the pro-war Putin critics are in trouble. The machinery of oppression needs feeding, and a security state doing a markedly poor job against Ukrainian intelligence has to go for easy victories.

They seem surprised that the system could turn against them. The Angry Patriots in their own statement wrote: “Igor Ivanovich openly and reasonably criticized the actions of the authorities, including the president, but the freedom of speech that the state provided testified that the country’s leadership complied with Article 29 of the Russian Constitution. Today, confidence in this has been undermined—we see that processes are taking place in our country that demonstrate the departure of the representatives of the authorities from the basic values.”

These same groups, of course, spent years cheering on the repression of liberals.

But Putin may be in trouble. Girkin’s Club of Angry Patriots is slowly becoming a formidable force in the Russian political sphere—somehow, they’ve acquired marginals and extremists from all sides and colors around them. Communists, national Bolsheviks (who wear red armbands and glorify racial purity, yet call Ukrainians Nazis), failed economists, imperialists, and chauvinists. And to all of them, Girkin has become a symbol of this true Russian patriotism. If Putin wanted to shut him up, he should have done it a long time ago. Currently, Girkin’s arrest will only serve as a symbol of martyrdom for his movement’s followers, some of whom already serve in the armed forces.

Unfortunately for the Club of Angry Patriots, they forgot to trademark the name in the European Union, and now I own it. I trademarked the name of Girkin’s organization in English and Russian and both of his logos so that he couldn’t open cells in the West. Using this, admittedly ridiculous, branding I’ve raised around $20,000 for the Ukrainian war efforts. (And if any of my readers want to use it, I’ll happily grant the right to anyone who supports Ukraine.)

Inside Russia, the club may be facing more serious problems than a Latvian journalist with a sense of mischief. One possibility for the near future is that Putin’s control keeps tightening and Russians’ sense of relative freedom, by autocratic standards, starts to slip away. Russia becomes the next North Korea, any freedoms whatsoever are suppressed, and they lose the war because sycophants do not make for good generals. That brings its own renewed chaos for the motherland; losing states aren’t happy places. Another is that the right fully turns on him—making his rule look weaker than ever. Internal strife seems inevitable.

The fact that Girkin, who can’t even afford a dentist or a car, has been arrested as a threat shows that Putin is no longer clearly in control and that the old KGB officer is slowly succumbing to paranoia. After all, if such a man seems to be a serious threat to a leader, then clearly something has been broken in the structures of power. Girkin himself might not deserve to be in a Russian jail—but he does deserve to be in The Hague.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian military bloggers continued to post analysis that is skeptical of Russian efforts and increasingly in-line with Western assessments of Russian military failures in Ukraine. One such blogger, Igor Strelkov, claimed that the Russian offensive to take Donbas has ultimately failed and that “not a single large settlement “has been liberated. Strelkov even noted that the capture of Rubizhne is relatively insignificant because it happened before the new offensive in Donbas had begun. Strelkov stated that Russian forces are unlikely to liberate Donbas by the summer and that Ukrainian troops will hold their positions around Donetsk City. Strelkov notably claimed that Russian failures thus far have not surprised him because the intent of Russian command has been so evident throughout the operation that Ukrainian troops are aware of exactly how to best respond and warns that Russian troops are fighting to the point of exhaustion under “rules proposed by the enemy.” The continued disenchantment of pro-Russian milbloggers with the Russian war effort may fuel dissatisfaction in Russia itself, especially if Moscow continues to press recruitment and conscription efforts that send poorly-trained cannon-fodder to the front lines.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

il ministro della Sanità russo Mikhail Murashko vuole assicurarsi che ogni africano sia vaccinato al massimo.

Il Forum economico e umanitario russo-africano, tenutosi a San Pietroburgo alla fine di luglio, è stato un completo successo sotto ogni aspetto.

Erano presenti i più grandi nomi degli affari e dell'azione umanitaria legati all'Africa, incluso il principale filantropo russo:

Com'è che il signor Prigozhin frequenta gli africani in un hotel di lusso a San Pietroburgo, mentre Igor Strelkov - che ha denunciato Prigozhin come traditore e ha definito la "Marcia su Mosca" di Wagner un atto di tradimento - è in custodia a Mosca?)

Ma il Forum economico e umanitario russo-africano del 2023 non è stato solo un'opportunità per i signori della guerra di condividere suggerimenti e trucchi.

Il ministro della Sanità russo Mikhail Murashko e il direttore del Gamaleya Center Alexander Gintsburg hanno partecipato alla conferenza per sostenere legami più stretti tra Mosca e l'Africa.

Fonte: www.minzdrav.gov.ru

africa finitissima.....:-)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Igor Strelkov at the Meachansky court in Moscow.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

welp. igor “strelkov” girkin - wanted war criminal, bitter old man, and fascist cassandra - got arrested by the FSB. wonder if prigozhin’s little mutiny was more succesful than we thought.

#russia#ukraine#wagner mutiny#I'm going to miss his dooming a little bit#and what I really want is to see him in the hague

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian ex-warlord asks to fight in Ukraine

Russian nationalist Igor Girkin, who was convicted of extremism back in January, will ask to be sent to fight in Ukraine. Girkin, also known by his alias “Strelkov,” is an ex-intelligence officer who Source : kyivindependent.com/russian-e…

0 notes

Text

Jailed Russian Nationalist Girkin Seeking to Fight in Eastern Ukraine Despite Ban

The wife of jailed Russian nationalist and ex-rebel commander Igor Girkin said Wednesday that her husband is seeking to clear his criminal record and serve at the front line in eastern Ukraine.

Girkin, a convicted war criminal in the West better known by his pseudonym Igor Strelkov, was arrested in July after criticizing Russian President Vladimir Putin for what he described as incompetence in managing the war against Ukraine. In January, the 54-year-old was sentenced to four years in prison for “inciting extremism.”

Read more | Subscribe to our channel

https://nn.org.ru

0 notes

Text

Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties (CCL) was one of the three laureates that shared the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize. Founded by the human rights lawyer Oleksandra Matviichuk, the NGO was honored for its outstanding work documenting war crimes, human rights violations, and abuses of power, chiefly in Ukraine, but often extending beyond its territory. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, the center’s database grew to hundreds of thousands of records describing wartime atrocities committed by the invading military. Meduza special correspondent Lilia Yapparova spoke with Oleksandra Matviichuk about how human rights advocates collect information, cope with stress, and collaborate with their peers in Russia.

— How did you become a human rights advocate?

When I was still in high school, I met the Ukrainian writer and philosopher Yevhen Sverstiuk. He took me under his wing and introduced me to other Ukrainian dissidents. The example of those people — who had the courage to speak what they thought, and to live as they spoke, in their struggle against the totalitarian Soviet machine — inspired me to apply to law school, so that I could also defend human dignity and freedom.

In 2007, the Helsinki Commission for Human Rights proposed setting up аn NGO in Kyiv, to monitor rights and liberties not just at the national level, but also going beyond Ukraine’s immediate state borders. At that time, Ukraine looked like an exception among the neighboring states. Russia was already passing new repressive legislation. In Ukraine, though, after the Orange Revolution, the government was trying to enact some democratic reforms. You could breathe easier there, and it was easier to work.

This is how the Center for Civil Liberties came into being. I was its first director, and I must admit that those who inspired us to establish it had been mistaken about scope. In a few years, Viktor Yanukovich became president and set to work on a power vertical, smothering all freethinking. So, instead of working at an international level, as we’d envisioned, CCL had to give more and more attention to rights and liberties in Ukraine proper.

At that time, Ukraine was literally duplicating the Russian legislation. When Russian human rights activists called their State Duma a “crazed printer,” we told them we had a “crazed copy machine.” Whenever Russia passed new legislation, it would resurface after a while in our own country, in the shape of legislative proposals.

— In 2014, CCL became the first human-rights organization to send mobile groups to Crimea and the Donbas. What did you encounter there?

We dispatched our first mobile group in late February 2014, when the so-called “green men” started appearing around Crimea. Russia and Putin personally denied that these were their combatants. At the time, we didn’t even realize this was the start of a war. It was the time of the Revolution of Dignity. We slept for three or four hours a night, because our new initiative, Euromaidan-SOS, was getting hundreds of reports from people who had been beaten, tortured, or prosecuted on fabricated charges. We had neither time nor energy for reflection.

Later, in April 2014, when Igor Girkin-Strelkov started gaining notoriety, I got a call from a colleague in the Russian human rights center Memorial (which has since been dissolved). I remember him saying, “Sasha, our death squads have come to your country.” That phrase struck me as something that belongs in a novel. It was all the more strange to hear it from that particular person, who is usually very restrained. He has worked in numerous war zones in the past. But then we started seeing cases: disappearances, torture, extrajudicial killings in Russian-occupied territories… And I finally understood what he’d meant.

— After February 24, 2022, you got multiple local human rights organizations involved in documenting the Russian war crimes. How does this work?

We pooled our resources together with dozens of organizations, mostly regional, in an initiative called Tribunal for Putin. We set an ambitious goal of documenting every criminal episode that took place in each village, down to the smallest ones, in every part of Ukraine.

Apart from the practices we had documented before — unlawful detentions, abductions, civilian torture, and killings — we were now dealing with all kinds of crimes against humanity: unlawful deportations, executions, and the use of prohibited weapons in densely populated areas.

We interview witnesses and victims in liberated territories and monitor the still-occupied territories. We also check open-source data. Our database now has over 49,000 records of international crimes, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

— How do you find witnesses?

You would have to ask members of the mobile groups who worked in liberated regions like Kyiv, Kharkiv, or Kherson. They had no trouble finding either victims or witnesses because you can come to any village, and something will have happened there. Every village has this huge amount of pain. It’s human suffering we document.

— How do human rights monitors cope with their work?

There are some things you just can’t prepare for. I still haven’t found the words to explain what it’s like to live amid a full-scale invasion. It’s a total rupture of social fabrics and structures. Everything you thought was just part of normal life crumbles. Things you took for granted vanish. You lose control over your life because you can’t make any plans, even for the next few hours, since there might be an air-raid alert at any moment. So you just keep working, even as you realize that neither you nor your loved ones have any safe place to hide from Russian missiles.

Every person has limits. I never interview children, for example — I just don’t think I could do it. I have a lot of empathy in general, and when it comes to kids… But lots of my peers work in children’s rights advocacy. It’s thanks to their work that I know the story of a little boy who lived in Mariupol with his mom. While the Russian army was steadily demolishing their city, he and his mother were in a bomb shelter. The boy still got wounded. He couldn’t walk, and his mother, who had also been wounded, managed to drag him off to some safe place. And she died there, in his arms. I just don’t know how anybody can survive something like that.

— How hard is it to document sexualized violence?

These are considered “crimes of shame,” because victims of sexualized violence often cannot talk about what happened, either to law enforcement or to human rights advocates. The first thing these people need is to recover. Later, they can decide whether they want to testify and take action on their case.

I’ve interviewed people who had been kept in detention together, in the occupied parts of the country. Witnesses would talk to me about recurrent rapes, but the victims themselves couldn’t speak a word about that sexualized violence, even though they’d describe other kinds of torture, down to the most terrifying details.

Sexualized crimes target the whole community: their victims feel ashamed; the victims’ loved ones feel guilt since they couldn’t prevent what happened; and everyone else feels fear since they can also be victimized. This decreases the group’s overall capacity for resistance.

In March 2022, we wrote a booklet for the survivors of this type of violence, and it had a section that really speaks to our current reality. We wrote it in consultation with Ukrainian gynecologists. It was about how to help yourself if you’ve been raped in occupied territory and can’t even get to the doctor.

— What about the people who were captured by the Russian military?

I’ve interviewed hundreds of people since 2014. People who had their nails pulled out and their knees shattered, people who had been hammered into wooden boxes, people whose tattoos had been cut off their bodies and who had their limbs cut off, or who had electric cables put to their genitals. Anything the Russian military and secret services could imagine — they did it, just because they could. This defies explanation. There isn’t a rational explanation for torture. But this defies even irrational explanation.

One man told me that he still keeps hearing the crackling of scotch tape. Where he was being held, the captors immobilized people with tape before beating them. Some people say the hardest part was not being tortured but hearing others, when people begged to be killed instead of suffering like that. I’ve heard about a father and his son, who were tortured in front of one another, to make it even more painful.

The common denominator in all cases of torture is this: the Russians did it simply because they could.

— How do you track what happens to Ukrainians in occupied territories, or people who were taken to Russia’s temporary housing facilities, orphanages, and jails?

It’s not always possible to do this by legal means, but there’s also human connection. People who want to help, who are trying to save someone — there are people like that everywhere, in occupied parts of Ukraine and in Russia, too. We also have all the latest digital tools, which probably make this the best-documented war ever. They don’t even have to be present in person to identify criminals. This is something that the perpetrators themselves don’t quite grasp.

— How do you explain the Russian military’s cruelty?

War crimes are part and parcel of how Russia engages in warfare. They deliberately terrorize civilians to break down resistance. They instrumentalize human suffering in this way. When I studied in law school, we were told that this is a hallmark of weak armies that don’t feel secure and in control.

The Russian army also committed war crimes in Chechnya, Georgia, Mali, Syria, and the Central African Republic — without ever really being punished. This culture of impunity makes them think that they can do anything to people.

— Do you track the war crimes committed by the Ukrainian army?

We track all war crimes, regardless of who commits them. This has been our position since 2014. It would be strange if we didn’t do this as human rights advocates. But because we’ve documented everything since February 24, 2022, in a single database, I can say with absolute certainty that the Russian military has committed most of the crimes on record. But you don’t measure human rights in percentages. Every single violation is terrible.

War presents a massive challenge to our value systems, but Ukrainian society still has some capacity to intervene: to prosecute, to publicize, and to allow international organizations to visit its POWs. I’m not trying to say that everything works smoothly: We’re a country in transition, and our justice and law-enforcement systems are still reforming after the fall of the authoritarian regime. But at least we have these possibilities, while Russia doesn’t.

— You have said that there isn’t an international court that could hold Putin responsible for the crimes of his regime. What did you mean by that?

This is a really interesting question. The Russian regime being what it is, the so-called developed democracies spent decades averting their eyes from what Russia was doing at home all that time: persecuting the press, jailing the activists, suppressing the protests. And they kept shaking hands with Putin, doing business as usual, building the gas pipelines. But when evil goes unpunished, it grows.

Why doesn’t the International Criminal Court have any jurisdiction while Russia commits all kinds of crimes — war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and military aggression? This is because the countries of the Rome Statute have defined aggression too narrowly, forfeiting their right to interfere. It isn’t Putin who stands in their way; this is their own responsibility.

— Will the ICC’s arrest warrant for Putin be enough to ensure that he faces justice?

Putin cannot travel to South Africa anymore, since its authorities have a duty to arrest him. I realize that they don’t particularly want to act on this special duty, but the fact is that they have to. This is to say that even people who might prefer to engage in “business as usual” must recognize that they are shaking hands with a formally indicted war criminal. Some people say that Putin doesn’t need to shake hands with anyone. But personally, I think this does matter to him and his pathologically inflated ego.

History tells us that authoritarian regimes crumble in the end and that their leaders, who once considered themselves untouchable, ultimately face justice in court. Serbia, for example, didn’t want to deliver Radovan Karadžić or Slobodan Milošević — they were its national heroes. But when it had to rebuild civil relations with other countries, it finally had to comply.

— What changes to international law would make it easier to hold the perpetrators of war crimes responsible?

Before changing the law, we need to change our way of thinking. Of course, the justice system itself can be improved, but even the system already in place isn’t working because politicians continue to view the world through the optics of the Nuremberg trials, which condemned the Nazi leadership — that is, the leadership of an already-defunct regime. This was a very important step for the past century, but we are living in a new century when it’s time to stop subordinating international justice to authoritarian regimes.

We must demonstrate that when someone commits international crimes, they will be held responsible, regardless of their regime’s size and nuclear arsenal. I think of this as the historic task of our generation, and how we address this will determine what kind of world we will inhabit in the future.

— Does the Nobel Prize help your work?

The Nobel Prize helps us have our voices heard. Human rights advocates from our region were ignored in the past, even though we’ve said the exact same thing for decades. For decades, we’ve been saying that a country that violates the rights of its own citizens is a danger to its neighbors and the rest of the world.

— Many Ukrainians objected to the Nobel Prize going to human rights advocates from three countries: Ukraine and the two countries with which Ukraine is at war.

When you see a headline with three words, “Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus,” separated by commas, this immediately brings back the fusty Soviet memories of “fraternal nations,” together with the feeling of being coerced back into that threesome. Of course, everyone has grasped by now that there weren’t any “fraternal nations” in the USSR, where one nation, one language, and one culture dominated all the rest. The others could make presentations at ethnic festivals.

Of course, in wartime, when Russia and Belarus are acting as aggressors while Ukraine has to defend itself, the triple award alienated some people. We, for our part, have tried to convey that the prize honors people rather than their countries, and those people have been working together for a very long time. Both before and after 2014, we worked very closely with Russian human rights activists. We share the same vocation with them, and the same framework of values.

When we were just starting out with human rights monitoring in Crimea and the Donbas, we relied on the experience of joint mobile groups that previously worked in Chechnya. I remember calling my Russian colleagues, asking them, “Do you have any materials? Instructions? Questionnaires? We’re sending in our people who will have to work on wheels.”

And mind you, thousands of our civilians are now jailed in Russia. Where we don’t have any access, our work is done with the help of Russian human rights defenders.

— After more than nine years of monitoring Russia’s human rights violations and war crimes, do you sometimes feel helpless?

“Helpless” is how Russia would like us to feel. The feeling of helplessness determines the whole modus operandi of Russian society itself. It shows up in statements like “well, what are we going to do,” “the government knows better,” “we don’t know all the facts,” and “I’m just a cog in the machine.” In reality, this is a craven position and doesn’t save anyone from responsibility. The appropriate position is resistance.

When the full-scale invasion started, it wasn’t just Putin who thought he’d capture Kyiv in three days. Our international partners thought so, too. No one believed in us, but this struggle for our freedom was the Ukrainian people’s decision, and the people turned out to be much stronger than they thought. So, when the so-called ordinary people get mobilized en masse, this can change history.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A prominent Russian milblogger accused unspecified senior officials within the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) of preparing to censor Russian milbloggers on October 14. Prominent Russian milblogger Semyon Pegov (employed by Telegram channel WarGonzo) accused “individual generals and military commanders” of developing a “hitlist” of Russian milbloggers that the MoD seeks to criminally prosecute for “discrediting” the Russian MoD’s activity and the Russian special military operation in Ukraine. Russian news aggregator Mash reported on October 14 that Chief of the Russian General Staff Valery Gerasimov personally signed an order instructing Russian state media censor Roskomnadzor to investigate prominent Russian milbloggers Igor Girkin (also known as Igor Strelkov), Semyon Pegov (WarGonzo), Yuri Podolyaka, Vladlen Tatarsky, Sergey Mardan, Igor Dimitriev, Kristina Potupchik, and authors of the Telegram channels GreyZone and Rybar. Unspecified Russian authorities detained the manager of several milblogger Telegram channels linked to Wagner financier Yevgeny Prigozhin on October 5. Moscow police previously arrested and released Pegov under unusual circumstances (reportedly for drunkenly threatening a hotel administrator) in Moscow on September 2. The situation will likely become clearer in the coming days. A key indicator for the status of a crackdown on Russian milbloggers will be any status update from former Russian militant commander and nationalist milblogger Igor Girkin. Girkin has not posted since October 10—a significant change in his behavior given that he usually posts multiple times daily.

the girls are fighting, etc.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The former Minister of Defense of the Donetsk People's Republic, Igor Strelkov-Girkin, has been sentenced to four years on charges of "incitement to extremism."

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] The lawyer for the arrested ex-leader of Kremlin-backed separatists in Ukraine, Igor Girkin (aka Strelkov), says the materials of his client’s case have been classified as "top secret." [ad_2]

0 notes