#i’ve been completing the interrogation sequences on my first try without a guide!

Text

also towa offering to get rei off every time rei’s inconvenienced. my guy just say you want him.

#slow damage#ok he’s only asked like twice so far but still lol#rei could stub his toe and towa would be like ‘oof. you know what will make you feel better? a blow job’#also towa being artistically obsessed w rei always sketching him and shit#i was like uhmm?? paint him???#but apparently he’s tried before……very interesting 🤔#tho i don’t know the context of it yet i haven’t gotten that far#i’ve been completing the interrogation sequences on my first try without a guide!#when i succeeded in kirihara’s interrogation i was like Slay.#then i saw the following scene and i was like Not So Slay. lmao#ok i’m posting way too much about this game i gotta go to bed#once again another bl visual novel has a chokehold on my brain#michi yaps

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE YEAR IS 2020 AND I WATCHED NEON GENESIS EVANGELION FOR THE FIRST TIME, PART 13

Episode 25.

I spend twenty minutes after the episode ends trying to articulate what I think happened to my friends, gesticulating wildly.

The episode starts with a condensed version of the last upsetting bits of the previous episode and thus sets the ground for my difficulty in expressing my thoughts on it because of the imperfect intersection of linear narrative and metaphorical examination of selfhood. I've been trying to follow the show as a narrative, even as things dissolve, but here everything just goes STOP NO CONTEXT JUST IDEA AND INTERNAL INTERROGATION which I think I follow but I have difficulty following WHILE ALSO thinking about giant robots.

Something bad happened after the events of the last episode and maybe in the overall narrative structure that's all that matters? I guess this episode is about the question of what the end goals of all the barely understood players are vis-à-vis humanity through Shinji et al.

How can we be our fullest self? What and who informs who that self is? The passive approach, as seen in Shinji, isn't it. You cannot only do what you are directly told to do and you can't intuit what other people want you to do as unspoken directions.

The isolationist approach, as seen in Asuka, isn't it, either. Trying to act and live above and without human connections or direction has made her sense of self the most fragile. She's just a shell projecting an ideal around a core of hatred.

Misato is there as, perhaps, the end result of trying to live life like Shinji into adulthood (the result of Asuka's approach is evident because she's shattered), a projected false self created to fulfill the outside expectations of others while the inner self gets lost.

Rei I feel is the one who is closest to having it 'right' insomuch as there can be a right way to be a human being (and perhaps part of what Evangelion and its characters are grappling with is that there isn't or if there is, it's not a simple thing). She recognizes that who Rei is is shaped by Rei's interactions with other people and the passage of time and I think that Rei 3's apparent rejection or turn on Gendo's influence is because she knows that's not the entirety of it. Everyone is confronted to some degree by the fact that the version of themselves seen by other people is flawed but in Rei's case she's able to know it in a profound way because she is aware of the previous Reis and their memories but also of herself as distinct from them. So Shinji knows her but he doesn't Know Her and much of what Rei knows of others is removed, the Rei deaths and recreations putting a barrier between a direct human connection. The human connection is key but perhaps the degree to which so much of it is abstracted in Rei is why she isn't fully emotionally engaged as a person, even when her understanding of personhood is so much fuller than the others. No human connection leads to Asuka: fragile and quickly destroyed. Shinji recognizes the importance of the human connection, maybe, but fails to enact the how and in its place he has the projections of what he thinks other people want guiding him.

The people in our hearts aren't real people but just manifestations of our self speaking through puppets that look like people we know and can't substitute for human connection and create a similarly false self for the benefit of the false people projections (Misato).

Shinji's fear of being hurt by human connections results in his inability to make human connections and his holding himself up to the standards of imagined human connections which are unsatisfying and disappointing to everyone, including him.

Gendo's Human Instrumentality Project seems to be about recognizing the need for human connections, specifically individuals filling needs for each other that cannot be filled by the individual alone, both for the pursuit of fulfilling the need to find the true self but also taking humanity beyond humanity. I think it's because Gendo has sublimated his grief and sense of loss with respect to his wife into viewing the ability of individuals to obtain fulfillment and then lose it as a weakness that can be overcome.

If all of humanity loses its individuality and turns into the orange tang all humans are always complete and cannot be made incomplete by losing part of themselves. This is too much connection and gross, indistinguishable. What is the point of this if there is no individual?

Right now it looks like all approaches are imperfect and lead to failure, certainly in the context of Evangelion and these characters.

Visually everything is very cool in this episode even though the budget limitations are obvious. The work arounds are creative and inform the substance of what's being said, I think? There's distortion and dissolving and isolated figures on foldout chairs under spotlights.

My favourite thing is how the false characters, the characters talking to the real characters in the chair, are clearly drawn differently, badly, off model. Something is done to indicate their lack of realness, especially the false Shinji in Misato's heart.

I'm sorry if this commentary has become increasingly boring, I'm sorry if I'm doing or talking about Evangelion wrong or badly or pointlessly. I've really enjoyed it. This concludes my report on the penultimate episode of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

The final episode behind the cut.

Episode 26.

I appreciate the honesty of opening the episode with text that basically announces "look we don't have the time to explain everything so we're just going to explain it as it pertains to this microcosm called Shinji". It's a very clever/honest sort of meta acknowledgement of MAN THE BUDGET OOPS but I feel it's also in a way of framing the psychological aspect of the narrative as something that is not unique to Shinji but Shinji is merely the lens through which something more universal is viewed.

The episode seems to be divided into four distinct sections. The first bit is a ramped up version of the meditative internal discussions that have become increasingly frequent during the series. Interrogation by on screen text asking questions like are you happy, why aren't you happy, what do you want, why do you want this, why do you do that ... some of them very basic therapy sort of questions, others being refinements of that, questions meant to prompt you to look inward for an answer only you have.

But although we're told that this is an examination of Shinji sometimes Asuka is answering, sometimes Rei is answering. Sometimes they're asking the questions. Sometimes other characters are asking or elaborating, unseen.

Previously I've talked about feeling like narrative-wise things have been dissolving, when I try to recall a sequence of events, but here what's dissolving is the distinction between the characters because the experiences are unique but the feelings are inherently universal.

There's a lot of different things going on here, visually. Still portraits, reused footage from previous episodes, repeated shots of a rotary phone with the cable cut really sticks in my mind for some reason, what seem to be actual black and white photos of contemporary Japan. There's a universal quality and it's also how everything around you, all the people and experiences, make up the you that you are, shown with an outline of Shinji that's filled with rapidly flashing poorly imposed images of others that don't fit in his outline. It's cool.

That's when the episode transitions to its second bit which is, like, I don't know. It's a bit student film, it's a bit like that Loony Toons bit where Daffy Duck is talking directly to the animator who can erase and redraw him at will. It's barely animated in parts.

I had this understanding that Evangelion ran out of money near the end and that the last episode was barely animated at all and I think I assumed it would be like how I understand the second disc of Xenogears to be, just ... text because we can't do assets? But it's not. It's unpolished and sketchy and minimal, in spots just pencil drawings or roughly coloured in with markers, at one point it's just wave forms? But it was sad and weirdly beautiful and it felt like an extension of Shinji's internal struggle for meaning and understanding. Maybe because the lack of budget gives it an aesthetic similar to a student or art school film, it informs the material with a sincerity that I feel would be lacking in a more polished, traditional product. The fewer hands that can be felt in something the more /authentic/ it feels.

I, at least, have a greater patience and a great appreciation for something when I feel an authentic quality from it, even though that's only my perception. Form and substance compliment each other here, even if it's just because of budget constraints.

There's a really good part where it's just Shinji in a white void and it's, you know, about how that's the safest because there's nothing constraining him because he's the only thing, but it feels empty because how do we know what we are if we have no references. So a horizontal line is drawn and that's the ground in this white void and Shinji is then standing on the ground and it's reassuring, it's a reality that simultaneously limits your options but in limiting them defines what they are. It's just ... good.

Once things have been completely broken down it's time to I think reassemble them and that's the third part of the episode where Shinji wakes up in an otoge game where everything is good and normal and Asuka's his childhood friend, his mother is alive (but still faceless) and his father ... also exists and is not being actively cruel but hidden behind a newspaper, similarly faceless, existing but known (he's at the table, Yui is in the kitchen with her back always to the camera), Misato's his hot teacher, Rei is the new transfer student ... There's running to school with toast in mouth (from otoge Rei). Shinji's just a Normal Teen (but the normalcy is false, this weird artificial hyper normalcy that contrasts with the sad, raw realness of Shinji's life in Tokyo 3).

That's on the stage that Shinji is watching from his stool in the empty gymnasium with Misato and it goes dark and it's like ... this is another reality but I don't think it's meant to be a quantum thing but an example of the potential of, like, /imagine/ a you who is happy. So this is the fourth part of the episode and it's characters, every single character, interrogating Shinji, pointing out Shinji's flaws, and giving him ... advice? Guidance? A lot of it is ... bad. The characters recognize real problems Shinji has, that Shinji knows he has and then they tell him things which are presented as, for lack of a better term, 'solutions' to his problems of self. But a lot of them are not actionable. Some of them are little more than 'you hate yourself but have you considered ... not hating yourself?'

Much like when Shinji gets praised, once, by his father for what he did in the robot and that is assumed to be good because it's good in comparison to the nothing he's received, the words Shinji gets here are presumed good because they're actual acknowledgement of his problems.

The result is Shinji standing on the earth, surrounded by the other characters, announcing that he is determined to care for himself, and they all applaud and congratulate him and it's weird. It's presented as happy but there's no emotion. No emotion in this climax of a series that has so effectively evoked so much emotion, raw and powerful and real and relatable. It's not happy. It's not sad, either. It's just an absence of sadness. It's this orange tang safety in muted absence of loneliness or danger. I think because Shinji is given good conclusions for his problems (self-worth and love have to come from within, you need to allow yourself to care for yourself or you'll never believe completely that others can care for you) but he's not shown a good path to get there. What people tell Shinji gives him an understanding of what the goal is (happiness) but none of the tools to get him to happiness, something he has no real personal experience with, so the ending he arrives at isn't authentic. It's a false construct, like the otoge realty.

It's not a good ending but I think it wants there to be a good ending and the viewer to recognize when a 'good' ending isn't really good. It's a lot to think about. This concludes my report on the final episode of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Captive Lover – An Interview with Jacques Rivette, Frédéric Bonnaud

(September 2001)

Translation by Kent Jones

This interview was originally published in Les Inrockuptibles (25 March 1998) and has been republished here with the kind permission of the author.

* * *

I guess I like a lot of directors. Or at least I try to. I try to stay attentive to all the greats and also the less-than-greats. Which I do, more or less. I see a lot of movies, and I don’t stay away from anything. Jean-Luc sees a lot too, but he doesn’t always stay till the end. For me, the film has to be incredibly bad to make me want to pack up and leave. And the fact that I see so many films really seems to amaze certain people. Many filmmakers pretend that they never see anything, which has always seemed odd to me. Everyone accepts the fact that novelists read novels, that painters go to exhibitions and inevitably draw on the work of the great artists who came before them, that musicians listen to old music in addition to new music… so why do people think it’s strange that filmmakers – or people who have the ambition to become filmmakers – should see movies? When you see the films of certain young directors, you get the impression that film history begins for them around 1980. Their films would probably be better if they’d seen a few more films, which runs counter to this idiotic theory that you run the risk of being influenced if you see too much. Actually, it’s when you see too little that you run the risk of being influenced. If you see a lot, you can choose the films you want to be influenced by. Sometimes the choice isn’t conscious, but there are some things in life that are far more powerful than we are, and that affect us profoundly. If I’m influenced by Hitchcock, Rossellini or Renoir without realizing it, so much the better. If I do something sub-Hitchcock, I’m already very happy. Cocteau used to say: “Imitate, and what is personal will eventually come despite yourself.” You can always try.

Europa 51 (Roberto Rossellini, 1952)

Every time I make a film, from Paris nous appartient (1961) through Jeanne la pucelle (1994), I keep coming back to the shock we all experienced when we first saw Europa 51. And I think that Sandrine Bonnaire is really in the tradition of Ingrid Bergman as an actress. She can go very deep into Hitchcock territory, and she can go just as deep into Rossellini territory, as she already has with Pialat and Varda.

Le Samourai (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967)

I’ve never had any affinity for the overhyped mythology of the bad boy, which I think is basically phony. But just by chance, I saw a little of L’Armée des ombres (1969) on TV recently, and I was stunned. Now I have to see all of Melville all over again: he’s definitely someone I underrated. What we have in common is that we both love the same period of American cinema – but not in the same way. I hung out with him a little in the late ’50s; he and I drove around Paris in his car one night. And he delivered a two-hour long monologue, which was fascinating. He really wanted to have disciples and become our “Godfather”: a misunderstanding that never amounted to anything.

The Secret Beyond the Door (Fritz Lang, 1948)

The poster for Secret Défense (1997) reminded us of Lang. Every once in a while during the shoot, I told myself that our film had a slim chance of resembling Lang. But I never set up a shot thinking of him or looking to imitate him. During the editing (which is when I really start to see the film), I saw that it was Hitchcock who had guided us through the writing (which I already knew) and Lang who guided us through the shooting: especially his last films, the ones where he leads the spectator in one direction before he pushes them in another completely different direction, in a very brutal, abrupt way. And then this Langian side of the film (if in fact there is one) is also due to Sandrine’s gravity.

The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

The most seductive one-shot in the history of movies. What can you say? It’s the greatest amateur film ever made.

Dragonwyck (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1946)

I knew his name would come up sooner or later. So, I’m going to speak my peace at the risk of shocking a lot of people I respect, and maybe even pissing a lot of them off for good. His great films, like All About Eve (1950) or The Barefoot Contessa (1954), were very striking within the parameters of contemporary American cinema at the time they were made, but now I have no desire whatsoever to see them again. I was astonished when Juliet Berto and I saw All About Eve again 25 years ago at the Cinémathèque. I wanted her to see it for a project we were going to do together before Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974). Except for Marilyn Monroe, she hated every minute of it, and I had to admit that she was right: every intention was underlined in red, and it struck me as a film without a director! Mankiewicz was a great producer, a good scenarist and a masterful writer of dialogue, but for me he was never a director. His films are cut together any which way, the actors are always pushed towards caricature and they resist with only varying degrees of success. Here’s a good definition of mise en scène – it’s what’s lacking in the films of Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Whereas Preminger is a pure director. In his work, everything but the direction often disappears. It’s a shame that Dragonwyck wasn’t directed by Jacques Tourneur.

The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946)

It’s Chandler’s greatest novel, his strongest. I find the first version of the film – the one that’s about to be shown here – more coherent and “Hawksian” than the version that was fiddled with and came out in ’46. If you want to call Secret Défense a policier, it doesn’t bother me. It’s just that it’s a policier without any cops. I’m incapable of filming French cops, since I find them 100% un-photogenic. The only one who’s found a solution to this problem is Tavernier, in L.627 (1992) and the last quarter of L’Appât (1995). In those films, French cops actually exist, they have a reality distinct from the Duvivier/Clouzot “tradition” or all the American clichés. In that sense, Tavernier has really advanced beyond the rest of French cinema.

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Of course we thought about it when we made Secret Défense, even if dramatically, our film is Vertigo in reverse. Splitting the character of Laure Marsac into Véronique/Ludivine solved all our scenario problems, and above all it allowed us to avoid a police interrogation scene. During the editing, I was struck by the “family resemblance” between the character of Walser and the ones played by Laurence Olivier in Rebecca (1940) and Cary Grant in Suspicion (1941). The source for each of these characters is Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, which brings us back to Tourneur, since I Walked with a Zombie (1943) is a remake of Jane Eyre.

I could never choose one film by Hitchcock; I’d have to take the whole oeuvre (Secret Défense could actually have been called Family Plot [1976]). But if I had to choose just one film, it would be Notorious (1946), because of Ingrid Bergman. You can see this imaginary love affair between Bergman and Hitchcock, with Cary Grant there to put things in relief. The final sequence might be the most perfect in film history, in the way that it resolves everything in three minutes – the love story, the family story and the espionage story, in a few magnificent, unforgettable shots.

Mouchette (Robert Bresson, 1966)

When Sandrine and I first started talking – and, as usual, I didn’t know a thing about the film I wanted to make – Bernanos and Dostoyevsky came up. Dostoyevsky was a dead end because he was too Russian. But since there’s something very Bernanos-like about her as an actress in the first place, I started telling her my more or less precise memories of two of his novels: A Crime, which is completely unfilmable, and A Bad Dream, a novel that he kept tucked away in his drawer, in which someone commits a crime for someone else. In A Bad Dream, the journey of the murderess was described in even greater length and detail than Sandrine’s journey in Secret Défense.

It’s because of Bernanos that Mouchette is the Bresson film I like the least. Diary of a Country Priest (1950), on the other hand, is magnificent, even if Bresson left out the book’s sense of generosity and charity and made a film about pride and solitude. But in Mouchette, which is Bernanos’ most perfect book, Bresson keeps betraying him: everything is so relentlessly paltry, studied. Which doesn’t mean that Bresson isn’t an immense artist. I would place Trial of Joan of Arc (1962) right up there with Dreyer’s film. It burns just as brightly.

Under the Sun of Satan (Maurice Pialat, 1987)

Pialat is a great filmmaker – imperfect, but then who isn’t? I don’t mean it as a reproach. And he had the genius to invent Sandrine – archeologically speaking – for A nos amours (1983). But I would put Van Gogh (1991) and The House in the Woods (1971) above all his other films. Because there he succeeded in filming the happiness, no doubt imaginary, of the pre-WWI world. Although the tone is very different, it’s as beautiful as Renoir.

But I really believe that Bernanos is unfilmable. Diary of a Country Priest remains an exception. In Under the Sun of Satan, I like everything concerning Mouchette [Sandrine Bonnaire’s character], and Pialat acquits himself honorably. But it was insane to adapt the book in the first place since the core of the narrative, the encounter with Satan, happens at night – black night, absolute night. Only Duras could have filmed that.

Home from the Hill (Vincente Minnelli, 1959)

I’m going to make more enemies…actually the same enemies, since the people who like Minnelli usually like Mankiewicz, too. Minnelli is regarded as a great director thanks to the slackening of the “politique des auteurs.” For François, Jean-Luc and me, the politique consisted of saying that there were only a few filmmakers who merited consideration as auteurs, in the same sense as Balzac or Molière. One play by Molière might be less good than another, but it is vital and exciting in relation to the entire oeuvre. This is true of Renoir, Hitchcock, Lang, Ford, Dreyer, Mizoguchi, Sirk, Ozu… But it’s not true of all filmmakers. Is it true of Minnelli, Walsh or Cukor? I don’t think so. They shot the scripts that the studio assigned them to, with varying levels of interest. Now, in the case of Preminger, where the direction is everything, the politique works. As for Walsh, whenever he was intensely interested in the story or the actors, he became an auteur – and in many other cases, he didn’t. In Minnelli’s case, he was meticulous with the sets, the spaces, the light…but how much did he work with the actors? I loved Some Came Running (1958) when it came out, just like everybody else, but when I saw it again ten years ago I was taken aback: three great actors and they’re working in a void, with no one watching them or listening to them from behind the camera.

Whereas with Sirk, everything is always filmed. No matter what the script, he’s always a real director. In Written On the Wind (1956), there’s that famous Universal staircase, and it’s a real character, just like the one in Secret Défense. I chose the house where we filmed because of the staircase. I think that’s where all dramatic loose ends come together, and also where they must resolve themselves.

That Obscure Object of Desire (Luis Buñuel, 1977)

More than those of any other filmmaker, Buñuel’s films gain the most on re-viewing. Not only do they not wear thin, they become increasingly mysterious, stronger and more precise. I remember being completely astonished by one Buñuel film: if he hadn’t already stolen it, I would have loved to be able to call my new film The Exterminating Angel! François and I saw El when it came out and we loved it. We were really struck by its Hitchcockian side, although Buñuel’s obsessions and Hitchcock’s obsessions were definitely not the same. But they both had the balls to make films out of the obsessions that they carried around with them every day of their lives. Which is also what Pasolini, Mizoguchi and Fassbinder did.

The Marquise of O… (Eric Rohmer, 1976)

It’s very beautiful. Although I prefer the Rohmer films where he goes deep into emotional destitution, where it becomes the crux of the mise en scène, as in Summer, The Tree, the Mayor and the Mediathèque and in a film that I’d rank even higher, Rendez-vous in Paris (1995). The second episode is even more beautiful than the first, and I consider the third to be a kind of summit of French cinema. It had an added personal meaning for me because I saw it in relation to La Belle noiseuse (1991) – it’s an entirely different way of showing painting, in this case the way a painter looks at canvases. If I had to choose a key Rohmer film that summarized everything in his oeuvre, it would be The Aviator’s Wife (1980). In that film, you get all the science and the eminently ethical perversity of the Moral Tales and the rest of the Comedies and Proverbs, only with moments of infinite grace. It’s a film of absolute grace.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (David Lynch, 1992)

I don’t own a television, which is why I couldn’t share Serge Daney’s passion for TV series. And I took a long time to appreciate Lynch. In fact, I didn’t really start until Blue Velvet (1986). With Isabella Rossellini’s apartment, Lynch succeeded in creating the creepiest set in the history of cinema. And Twin Peaks, the Film is the craziest film in the history of cinema. I have no idea what happened, I have no idea what I saw, all I know is that I left the theater floating six feet above the ground. Only the first part of Lost Highway (1996) is as great. After which you get the idea, and by the last section I was one step ahead of the film, although it remained a powerful experience right up to the end.

Nouvelle Vague (Jean-Luc Godard, 1990)

Definitely Jean-Luc’s most beautiful film of the last 15 years, and that raises the bar pretty high, because the other films aren’t anything to scoff at. But I don’t want to talk about it…it would get too personal.

Beauty and the Beast (Jean Cocteau, 1946)

Along with Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945), it was the key French film for our generation – François, Jean-Luc, Jacques Demy, myself. For me, it’s fundamental. I saw Beauty and the Beast in ’46 and then I read Cocteau’s shooting diary – a hair-raising shoot, which hit more snags than you can imagine. And eventually, I knew the diary by heart because I re-read it so many times. That’s how I discovered what I wanted to do with my life. Cocteau was responsible for my vocation as a filmmaker. I love all his films, even the less successful ones. He’s just so important, and he was really an auteur in every sense of the word.

Les Enfants terribles (Jean Cocteau, 1950)

A magnificent film. One night, right after I’d arrived in Paris, I was on my way home. And as I was going up rue Amsterdam around Place Clichy, I walked right into the filming of the snowball fight. I stepped onto the court of the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre and there was Cocteau directing the shoot. Melville wasn’t even there. Cocteau is someone who has made such a profound impression on me that there’s no doubt he’s influenced every one of my films. He’s a great poet, a great novelist, maybe not a great playwright – although I really love one of his plays, The Knights of the Round Table, which is not too well known. An astonishing piece, very autobiographical, about homosexuality and opium. Chéreau should stage it. You see Merlin as he puts Arthur’s castle under a bad charm, assisted by an invisible demon named Ginifer who appears in the guise of three different characters: it’s a metaphor for all forms of human dependence. In Secret Défense, the character of Laure Mersac probably has a little of Ginifer in her.

Cocteau is the one who, at the end of the ’40s, demonstrated in his writing exactly what you could do with faux raccords, that working in a 180-degree space could be great and that photographic unity was a joke: he gave these things a form and each of us took what he could from them.

Titanic (James Cameron, 1997)

I agree completely with what Jean-Luc said in this week’s Elle: it’s garbage. Cameron isn’t evil, he’s not an asshole like Spielberg. He wants to be the new De Mille. Unfortunately, he can’t direct his way out of a paper bag. On top of which the actress is awful, unwatchable, the most slovenly girl to appear on the screen in a long, long time. That’s why it’s been such a success with young girls, especially inhibited, slightly plump American girls who see the film over and over as if they were on a pilgrimage: they recognize themselves in her, and dream of falling into the arms of the gorgeous Leonardo.

Deconstructing Harry (Woody Allen, 1997)

Wild Man Blues (1997) by Barbara Kopple helped me to overcome my problem with him, and to like him as a person. In Wild Man Blues, you really see that he’s completely honest, sincere and very open, like a 12-year old. He’s not always as ambitious as he could be, and he’s better on dishonesty than he is with feelings of warmth. But Deconstructing Harry is a breath of fresh air, a politically incorrect American film at long last. Whereas the last one was incredibly bad. He’s a good guy, and he’s definitely an auteur. Which is not to say that every film is an artistic success.

Happy Together (Wong Kar-wai, 1997)

I like it very much. But I still think that the great Asian directors are Japanese, despite the critical inflation of Asia in general and of Chinese directors in particular. I think they’re able and clever, maybe a little too able and a little too clever. For example, Hou Hsiao-hsien really irritates me, even though I liked the first two of his films that appeared in Paris. I find his work completely manufactured and sort of disagreeable, but very politically correct. The last one [Goodbye South, Goodbye, 1996] is so systematic that it somehow becomes interesting again but even so, I think it’s kind of a trick. Hou Hsiao-hsien and James Cameron, same problem. Whereas with Wong Kar-wai, I’ve had my ups and downs, but I found Happy Together incredibly touching. In that film, he’s a great director, and he’s taking risks. Chungking Express (1994) was his biggest success, but that was a film made on a break during shooting [of Ashes of Time, 1994], and pretty minor. But it’s always like that. Take Jane Campion: The Piano (1993) is the least of her four films, whereas The Portrait of a Lady (1996) is magnificent, and everybody spat on it. Same with Kitano: Fireworks (1997) is the least good of the three of his films to get a French release. But those are the rules of the game. After all, Renoir had his biggest success with Grand Illusion (1937).

Face/Off (John Woo, 1997)

I loathe it. But I thought A Better Tomorrow (1986) was awful, too. It’s stupid, shoddy and unpleasant. I saw Broken Arrow (1996) and didn’t think it was so bad, but that was just a studio film, where he was fulfilling the terms of his contract. But I find Face/Off disgusting, physically revolting, and pornographic.

Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

His work is always very beautiful but the pleasure of discovery is now over. I wish that he would get out of his own universe for a while. I’d like to see something a little more surprising from him, which would really be welcome…God, what a meddler I am!

On Connaît la Chanson (Alain Resnais, 1997)

Resnais is one of the few indisputably great filmmakers, and sometimes that’s a burden for him. But this film is almost perfect, a full experience. Though for me, the great Resnais films remain, on the one hand, Hiroshima, mon amour (1959) and Muriel (1963), and on the other hand, Mélo (1986) and Smoking/No Smoking (1993).

Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997)

What a disgrace, just a complete piece of shit! I liked his first film, The Seventh Continent (1989), very much, and then each one after that I liked less and less. This one is vile, not in the same way as John Woo, but those two really deserve each other – they should get married. And I never want to meet their children! It’s worse than Kubrick with A Clockwork Orange (1971), a film that I hate just as much, not for cinematic reasons but for moral ones. I remember when it came out, Jacques Demy was so shocked that it made him cry. Kubrick is a machine, a mutant, a Martian. He has no human feeling whatsoever. But it’s great when the machine films other machines, as in 2001 (1968).

Ossos (Pedro Costa, 1997)

I think it’s magnificent, I think that Costa is genuinely great. It’s beautiful and strong. Even if I had a hard time understanding the characters’ relationships with one another. Like with Casa de lava (1994), new enigmas reveal themselves with each new viewing.

The End of Violence (Wim Wenders, 1997)

Very touching. Even if, about halfway through, it starts to go around in circles and ends up on a sour note. Wenders often has script problems. He needs to commit himself to working with real writers again. Alice in the Cities (1974) and Wrong Move (1975) are great films – so is Paris, Texas (1984). And I’m sure the next one will be, too.

Live Flesh (Pedro Almodóvar, 1997)

Great, one of the most beautiful Almodóvars, and I love all of them. He’s a much more mysterious filmmaker than people realize. He doesn’t cheat or con the audience. He also has his Cocteau side, in the way that he plays with the phantasmagorical and the real.

Alien Resurrection (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 1997)

I didn’t expect it as I was walking into the theater, but I was enraptured throughout the whole thing. Sigourney Weaver is wonderful, and what she does here really places her in the great tradition of expressionist cinema. It’s a purely plastic film, with a story that’s both minimal and incomprehensible. Nevertheless, it managed to scare the entire audience, while it also had some very moving moments. Basically, you’re given a single situation at the beginning, and the film consists of as many plastic and emotional variations of that situation as possible. It’s never stupid, it’s inventive, honest and frank. I have a feeling that the credit should go to Sigourney Weaver as much as it should to Jeunet.

Rien ne va plus (Claude Chabrol, 1997)

Another film that starts off well before falling apart halfway through. There’s a big script problem: Cluzet’s character isn’t really dealt with. It’s important to remember Hitchcock’s adage about making the villain as interesting as possible. But I’m anxious to see the next Chabrol film, especially since Sandrine will be in it.

Starship Troopers (Paul Verhoeven, 1997)

I’ve seen it twice and I like it a lot, but I prefer Showgirls (1995), one of the great American films of the last few years. It’s Verhoeven’s best American film and his most personal. In Starship Troopers, he uses various effects to help everything go down smoothly, but he’s totally exposed in Showgirls. It’s the American film that’s closest to his Dutch work. It has great sincerity, and the script is very honest, guileless. It’s so obvious that it was written by Verhoeven himself rather than Mr. Eszterhas, who is nothing. And that actress is amazing! Like every Verhoeven film, it’s very unpleasant: it’s about surviving in a world populated by assholes, and that’s his philosophy. Of all the recent American films that were set in Las Vegas, Showgirls was the only one that was real – take my word for it.I who have never set foot in the place!

Starship Troopers doesn’t mock the American military or the clichés of war – that’s just something Verhoeven says in interviews to appear politically correct. In fact, he loves clichés, and there’s a comic strip side to Verhoeven, very close to Lichtenstein. And his bugs are wonderful and very funny, so much better than Spielberg’s dinosaurs. I always defend Verhoeven, just as I’ve been defending Altman for the past twenty years. Altman failed with Prêt-à-Porter (1994) but at least he followed through with it, right up to an ending that capped the rock bottom nothingness that preceded it. He should have realized how uninteresting the fashion world was when he started to shoot, and he definitely should have understood it before he started shooting. He’s an uneven filmmaker but a passionate one. In the same way, I’ve defended Clint Eastwood since he started directing. I like all his films, even the jokey “family” films with that ridiculous monkey, the ones that everyone are trying to forget – they’re part of his oeuvre, too. In France, we forgive almost everything, but with Altman, who takes risks each time he makes a film, we forgive nothing. Whereas for Pollack, Frankenheimer, Schatzberg…risk doesn’t even exist for them. The films of Eastwood or Altman belong to them and no one else: you have to like them.

The Fifth Element (Luc Besson, 1997)

I didn’t hate it, but I was more taken with La Femme Nikita (1990) and The Professional (1994). I can’t wait to see his Joan of Arc. Since no version of Joan of Arc has ever made money, including ours, I’m waiting to see if he drains all the cash out of Gaumont that they made with The Fifth Element. Of course it will be a very naive and childish film, but why not? Joan of Arc could easily work as a childish film (at Vaucouleurs, she was only 16 years old), the Orléans murals done by numbers. Personally, I prefer small, “realistic” settings to overblown sets done by numbers, but to each his own. Joan of Arc belongs to everyone (except Jean-Marie Le Pen), which is why I got to make my own version after Dreyer’s and Bresson’s. Besides, Besson is only one letter short of Bresson! He’s got the look, but he doesn’t have the ‘r.’

* * *

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stolen Dreams

Find the thief Maroo and uncover the secrets of the Arcane Codices.

Previous story quest: Once Awake

Starting the quest

The quest is awarded by completing the Phobos Junction on Mars. After it is unlocked, it can be started at any time from the Codex. Stolen Dreams must be completed as a requirement for unlocking the Europa Junction.

Once the quest is started, the Tenno will receive an inbox message from the Lotus.

Inbox message:

INTERCEPTED MESSAGE: Grineer Commander Tyl Regor

The rat Maroo takes us for fools. Find her. We must recover the new Arcane Codex before she sells it to the Corpus. If she no longer has the codes, you may use any extraction techniques necessary to learn their whereabouts. This interrogation can be her punishment; she need not survive.

You are commanded,

Tyl Regor

Lotus: "This is unexpected. After decades of searching, the Grineer finally uncovered the last of the Arcane Codices, only to lose them to some thief. Tyl Regor must be livid, which means this 'Maroo' is in real trouble. I need to have a word with her before the Grineer do."

Ordis: "Arcane Codices? Why have I never heard of them? Ordis needs to do some research."

First Mission: Capture Maroo (Tharsis, Mars)

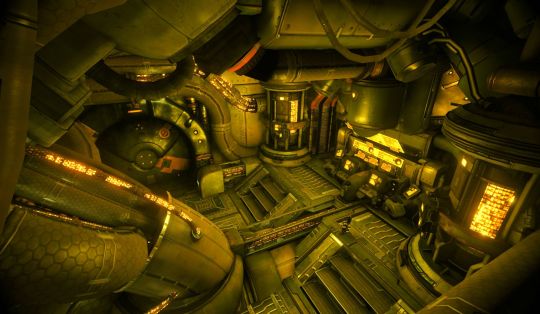

(Corpus Ice Planet concept art – Zeljko Duvnjak)

The mission takes place on the Corpus Ice Planet tileset, with Corpus enemies.

Lotus: "I have tracked Maroo to this Corpus outpost. Bring her to me for questioning. Be as persuasive as necessary; she may not want to come with us, but it's in her best interest."

Lotus: "The Arcane Codices have been a mystery ever since they were uncovered decades ago. They appear to be part of a set that was incomplete until the Grineer found this final code. Without the full set, nobody can agree on what exactly they are."

(upon spotting Maroo) Lotus: "Maroo, I am the Lotus. I come as a friend. You are in mortal danger and you need to come with us."

Maroo is armed with an Aklex and can cast Smoke Screen to temporarily become invisible. She will continuously speak unsubtitled lines until she is captured.

Maroo: "I'm not playing around, and I ain't got no business with a Tenno."

Maroo: "Don't come near me. I'm warning you!"

Maroo: "Nobody, but nobody catches Maroo!"

Maroo: "I don't take orders from anybody. Stay the hell back you tin-suits."

(when being captured, variant) Maroo: "Ahh hey! That kinda tickles!"

(when being captured, variant) Maroo: "Augh! It stings!"

[on board Orbiter]

The Tenno will receive an inbox message from the Lotus.

Inbox message:

DEBRIEFING LOG: Maroo

Once the severity of the Grineer capture order was made clear to her, Maroo was more than willing to accept our offer of protective custody. In exchange, she will aid us in locating the Arcane Codices.

The following is an excerpt from our debriefing with Maroo.

Maroo (video): "Oh, so you tin-suits want to know about that Arcane Codex? Heh, is that all? Okay here goes: Tyl Regor offered up big-time credits for me to pull the code from some strange machine on an Infested Orokin derelict. Thing is, I never much liked the Grineer, so the code I pulled, ain't the code I gave em. Haha, I guess they've finally figured that out? I bet you're looking to get your hands on the code? Too bad, I already sold 'em to the Corpus…. Now, if you were to make it worth my while? Maybe I'd tell you where they're keeping it…."

Second Mission: Take an Arcane Codex (Unda, Venus)

(Spy 2.0 hype image)

The mission is a Spy mission on the Corpus Outpost tileset, with Corpus enemies.

Maroo: "Listen up, ya tin-suits. With the Grineer itching to torture the life out of me, I've accepted your Lotus' offer of protection. In return, I'm gonna help your sorry behinds find that Arcane Codex."

Lotus: "My Tenno are quite capable, Maroo. Perhaps you would prefer it if we dropped you off outside the nearest Grineer mining asteroid?"

Maroo: "Wow. She always this much fun?"

Lotus: "Maroo?"

Maroo: "Fine. Here's the business. The Corpus are keeping the Codex in one of these fortified data vaults. You gotta break in and take what's yours without triggering the data destruction sequence."

There are three data vaults. Only one of them needs to be successfully hacked, but all three need to be attempted before the mission can be completed.

(upon approaching a data vault) Maroo: "The data vault is nearby. Do your best and try not to trip the alarms."

(upon completing the first data vault) Maroo: "You got that Codex. Why don't you see if the Corpus are hiding anything else in the other vaults?"

(upon extracting data undetected, variant) Maroo: "Hey, surprisingly impressive. You found the Codex, and the Corpus are none the wiser."

(upon extracting data undetected, variant) Maroo: "There's the codex! There might be hope for you after all."

(upon setting off alarms, variant) Maroo: "Now you've gone and done it. Get to that console, quick!"

(upon setting off alarms, variant) Maroo: "Smooth one, tin-suit… now, hurry up and get the data before it's destroyed."

(upon setting off alarms, variant) Maroo: "There's the alarms. Get moving!"

(upon extracting data after detection, variant) Maroo: "Well, it weren't pretty, but you got what we were looking for."

(upon extracting data after detection, variant) Maroo: "Nice recovery. Had me worried for a second there."

(upon failing the first data vault) Maroo: "Too slow! Good thing there's another vault. Try not to mess things up next time."

(upon failing the second data vault) Maroo: "Again? really? You know we're here to take the data, right? You've got one more chance."

(upon failing the third data vault) Maroo: "You managed to fail every vault. Maybe you're just not cut out for this type of work, tin-suit." [mission fails]

(after hacking the last vault) Maroo: "You've explored all the vaults and found that Arcane Codex. Your Lotus told me to tell you to get to extraction."

[on board Orbiter]

Ordis: "Operator, I've been looking into these Arcane Codices. Did you know the Corpus are in possession of three Codices and the Grineer two?"

Lotus: "And now the Tenno have one too. Nobody has ever examined them all together. That's our plan."

Ordis: "The Corpus seem to think they'll lead to some lost Orokin treasure."

Maroo: "Ordo, did you say treasure?"

Ordis: "It's 'Ordis', and, while just a theory, it is plausible."

Maroo: "Either way, it's right up my alley."

Third Mission: Take the Grineer Arcane Codices (Pantheon, Mercury)

(Spy 2.0 hype image)

The mission is a Spy mission on the Grineer Galleon tileset, with Grineer enemies.

Lotus: "Maroo tells me that the Grineer are storing their two Arcane Codices on this Galleon. You need to find both to complete this mission."

There are three data vaults, but only two need to be successfully extracted.

Maroo: "The Grineer claim the Arcane Codices will help them to a cure for cloning decay syndrome. I think that might be wishful thinking."

(upon extracting data, variant) Lotus: "That's it. That's an Arcane Codex."

(upon extracting data, variant) Lotus: "Good work. You found an Arcane Codex."

(after attempting all three data vaults) Lotus: "You've got the Codices and there is nothing more for us here. Get to extraction."

[on board Orbiter]

Ordis: "Operator, have you looked at these Codices? They're absolutely beautiful. Composed with such elegance and grace – I have never seen anything like them. Is there even an Operator capable of writing something so perfect?"

Maroo: "But you still have no idea what they mean, do you?"

Ordis: "…No, not really. Pfft… well, I wouldn't expect the likes of you to understand."

Fourth Mission: Take the Corpus Arcane Codices (Roche, Phobos)

(Spy 2.0 hype image)

The mission is a Spy mission on the Corpus Ship tileset, with Corpus enemies.

Lotus: "We've tracked down the remaining Arcane Codices to this Corpus facility."

All three data vaults must be hacked to complete the mission.

Lotus: "There are three data vaults and three Codices. Proceed with caution; if Corpus security destroy even one of these fragments, this mission will be a failure."

(upon extracting the third data vault) Lotus: "We have all the three Codices. You may extract now."

[on board Orbiter]

Ordis: "Operator, these make sense now! This is machine code, meant to interface directly with… a machine. Pity that machine has likely rusted into dust by now."

Maroo: "Ordo? Did you say something about a machine?"

Ordis: "Ordis' name is Ordis."

Maroo: "Yeah, yeah. Listen, that first Codex is in the derelict. I pulled it from some sort of machine."

Ordis: "Hmmm. I wonder, if we load the complete set of Arcane Codices back into that machine, would the code still execute?"

Lotus: "We're about to find out. Tenno, get ready to go into the Void."

Fifth Mission: Find the Arcane Machine (Alator, Mars)

(Grineer Settlement concept art – Branislav Perkovic)

The mission takes place on the Grineer Settlement tileset. Both Arid Grineer and Infested are present, fighting each other across the map. Both factions are also hostile to the Tenno.

Lotus: "Tenno, Maroo is the only person who has been on the inside of that derelict and lived to tell about it. She'll guide you through this mission."

Maroo: "This is it. Your Lotus has promised me a cut of whatever treasure you find, so don't you tin-suits go messing this one up. Get to the Void portal."

Lotus: "Maroo, I said 'if' there is any treasure."

Maroo: "Eh, c'mon, the Orokin were all about treasure, weren't they? The only question is, how much?"

A Void gate leads to an Infested Orokin derelict.

Maroo: "The Grineer have been trying to get inside this derelict for days, but the Infested keep tearing them to shreds. Your Lotus seems to think you'll do better. We'll see."

In the middle of a large room is an Orokin device emitting blue streams of energy. Floating suspended in the energy currents above the machine is what appears to be the skull of some large animal.

Maroo: "There it is, the machine I pulled the final Arcane Codex from. You've got the full set of Codices; upload 'em and say hello to treasure."

The Tenno must upload the Codices by interacting with the machine. A video transmission will appear on the HUD, consisting of a largely static-filled view of empty space with a mysterious voice speaking a cryptic message: "All is silent and calm. Hushed and empty is the womb of the sky." The audio, somewhat glitchy, will repeat once. After that, the skull will dissolve into smoke and disappear.

Maroo: "What just happened?"

Lotus: "The machine, it's gone. Tenno, watch out."

An Infested spawn pod nearby will produce an Arcane Boiler, simply a larger and blue version of the standard Boiler unit. It must be killed.

Lotus: "Tenno, I don't know if we got the answers we came for, but there's nothing more for us here. Exit the derelict and head for extraction."

Maroo: "What? Where's my damn treasure? I was told there would be treasure."

Lotus: "Whatever that was, it wasn't here for our benefit or yours. Only time will tell what we've just uncovered."

[on board Orbiter]

Ordis: "So, you're saying there was no treasure, no cure for cloning syndrome, no lost Tenno Cephalon?"

Maroo: "Ordo, there was nothing."

Ordis: "That really is a shame, Maroo. I am sorry."

Maroo: "Nah, I'm used to it. When you don't run with any of the major factions or Syndicates, the big paydays are few and far between. I'll manage. Listen, I can't say it hasn't been fun, but with the Arcane Codices gone, I think it's safe for me to venture back out into the wild. Cya, tin-suits."

Next story quest: The New Strange

[Navigation: Hub → Quests → Stolen Dreams]

4 notes

·

View notes