#i really need to stop reading the low rating letterboxd reviews

Text

one of the things that annoys me so bad right now is seeing letterboxd reviews about Lisa Frankenstein being like "she's such a horrible character", "those people didn't deserve to be killed" blah blah blah

SHUT UP

it's a horror romance!! a girl keeps a reanimated dead guy in her closet and falls in love with him! what did you think was going to happen? it's SUPPOSED to be fucked up and weird and that's part of its charm. quit being boring, let female characters (esp in horror) be messy and chaotic and morally gray.

#i really need to stop reading the low rating letterboxd reviews#i just get so curious about what people didnt like about movies#and most of the time they just make me annoyed lol#anywas go see this movie#i support womens rights and womens wrongs#lisa frankenstein#i love me a Frankenstein re-imagining#horror#horror hype#i live out my god complex through evil little scientists#<- thats my Frankenstein-esque media tag

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Last Artists.

“From the outside it seems like this dream scenario… but the truth is it took years working on drafts and wondering if anyone would ever read them.” —Joe Talbot on The Last Black Man in San Francisco.

A love story to San Francisco, to one grand Victorian house in particular, and to a life-long friendship, The Last Black Man in San Francisco was many years in the making. And it paid off: Joe Talbot picked up the Best Director prize at Sundance 2019 for his debut feature, a story drawn from the life of his best friend (and the film’s leading man), Jimmie Fails. A close-knit family of creatives grew around the project, and became a vital support system for Talbot when his father had a stroke just weeks before the shoot. Since January, critical accolades for the film have snowballed. Most recently, it appeared in our ten highest-rated features for the first half of 2019.

Letterboxd reporter Jack Moulton took the opportunity for a lengthy chat with Talbot about his remarkable debut feature. The interview contains a virtual masterclass in first-time feature film development (and the persistence required to see it through), along with some never-before-seen images shared exclusively with us by Joe. Also: some plot spoilers, which we’ve left until the very end.

Joe Talbot and Jimmie Fails in 2014, photographed by Talbot’s brother, Nat Talbot.

Thanks for agreeing to a good chat with us. Are you on Letterboxd? We have our suspicions that you might be.

Joe Talbot: Yeah. I love it. I found Letterboxd before we shot the movie. I use it to save movies to watch for later and look up movies people recommend. Occasionally I read the reviews of films I’ve just watched, they’re often really thoughtful.

Can we share your username? You could be the next Sean Baker.

The one I have right now is more of a lurking profile so it’s not very formal. I made one that’s a little more presentable for you under my name.

Are you in San Francisco right now?

I am. If you can hear my heavy breathing, I’m actually walking up one of the steeper hills that Jimmie and Montgomery crest in the movie and see the skyline. That’s what I do for every interview, I like to walk up the hill to put me in the film. Just kidding, this is the first time I’ve done it. I’m just walking with a friend and we’re about two thirds of the way up. Woo!

We’ve just published our halfway top 10 of the year. The Last Black Man in San Francisco is in second place, between Avengers: Endgame and Booksmart. How does this make you feel, and how do you cope with reviews (whether they’re full of praise or criticism)?

Wow, that means a lot. I find the reviews informative, though have to admit I don’t read too many of them. In general, it’s great to know that there are people that love movies enough to get into debates and write passionately, either about how much they loved them or didn’t like them at all. Having platforms like Letterboxd and finding those communities online can be really great, even if they’re not made up of people in your city.

Given that the film has relatively low stakes—it’s not life or death, it’s house or no-house—what gave you confidence that audiences would connect to Jimmie’s story?

I don’t know if we were ever confident. You never fully know. You hope that if you share something that has meaning to you then it will have meaning to others. That was our guiding light.

We finished the movie four days before the Sundance screening, so that was the first time watching it with any audience. I looked over at [Plan B producer] Jeremy Kleiner when the movie ended; he said ���the tweets are good”. I looked around and realized the whole audience were on their phone as soon as the credits rolled.

I only had a short film play at Sundance before [American Paradise in 2017, also starring Jimmie Fails] so I didn’t realize part of our culture now is the need to immediately respond to something—but luckily they were nice. It will be much more anxiety-inducing going into my next feature now that I know how all this works.

We wanted to make something that captured the San Francisco that we grew up in and feel very strongly about. We’ve travelled to Chicago, DC, New York, LA, and Atlanta with the film and I was surprised to see how much people were connecting to it. In a way, Jimmie and I say it is unfortunately universal because it means the same things are happening everywhere.

This idea has lived with you and Jimmie for a long time. Can you talk us through the journey of the film?

We’ve been informally talking about it for at least seven years and it’s gone through so many incarnations. We always envisioned it as the first feature that Jimmie and I would make after many years of making short films together. This story felt big enough in scope and there was a lot that we wanted to cover.

We wanted to tell a story about Jimmie and this Victorian home he once lived in and make it a valentine to the San Francisco we grew up in, that we see as being lost. We also wanted to celebrate all the wonderful people who are here that make this city what it is. That’s a big part of what we are afraid of losing: the very people that make San Francisco ‘San Francisco’.

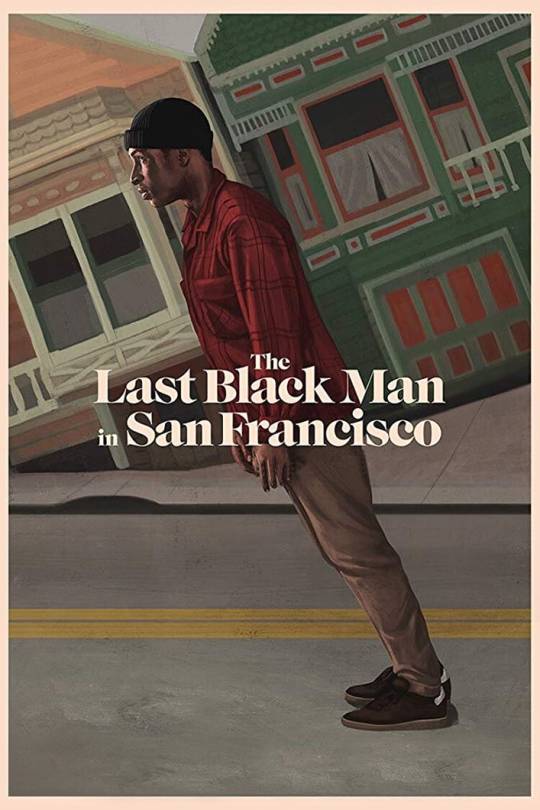

An alternative poster for the film, illustrated by Akiko Stehrenberger.

We both lived with my parents for five years—we ran our operation out of the living room there. The first thing we did was shoot a concept trailer for Vimeo. It was a five-minute piece of Jimmie skating through the city telling his grandfather’s story, much like the [feature’s] opening sequence, though I filmed it hanging out of the side of my brother’s car.

Afterwards we got emails from people saying they wanted to help; they would become our core collaborators on the film. Khaliah Neal, Rob Richert, Luis Alfonso de la Parra, Natalie Teter, Sydney Lowe, Prentice Sanders, Fritzi Adelman, Laila Bahman and Ryan Doubiago. They spent years with us, hashing out the script over my parents’ kitchen table and working with us to create a look-book, run an ambitious Kickstarter campaign, write grant proposals and so on.

We felt like these oddballs—the last artists in San Francisco. You get a lot of noes along the way, having never made a movie before, so it was the emotional support that helped us persist through the difficult times. We were excited to be learning together, as a group of mostly first-timers, and were constantly making things.

Our look-book was very elaborate, thanks to our stills photographer Laila Bahman. We built it as a website and staged the scenes as if we were filming the movie, with costumes and heavy art direction. We knew people we pitched were probably seeing materials from other filmmakers who were further in their careers and probably better writers than us. We knew we needed to show the world of the movie so that executives’ imaginations wouldn’t be running off with thoughts of Michael B. Jordan or Donald Glover; that this is Jimmie and this is the plaid shirt we want him in and this is his Victorian. It’s his story.

That helped us get into the Screenwriter’s Lab at Sundance, but I didn’t get into the Director’s Lab, which I was initially bummed about because I really needed that experience. Our Kickstarter was very successful and those backers created a grassroots ground-swelling around the movie that pushed it forward, even though it was difficult in pitch meetings as we weren’t the most bankable pair in such a risk-averse industry.

In a last-ditch effort, my crew and I decided to do our own Director’s Lab instead. We felt if it doesn’t work now then that might be it for Last Black Man. I’d never made a proper short with a budget before but a producer named Tamir Muhammad, who had a short-lived venture within Time Warner called OneFifty, gave us the money to make what would become American Paradise. It gave the crew a chance to get in the trenches together before moving on to a feature, and show the potential of what we could do.

The team who’d assembled from our concept trailer years before all worked on American Paradise, from Khaliah Neal, Rob Richert and Luis Alfonso down the line. We worked with production designer Jona Tochet and even the sound team of Sage and Corinne (who would all go on to work on Last Black Man). In a city increasingly devoid of artists, we felt we’d found our people.

The short was different from Last Black Man, but features Jimmie playing the same character. After it played in Sundance it got the attention of Plan B’s Christina Oh. They took a big leap of faith on us, only having ever made that short. There’s not a lot of people willing to do that.

Khaliah, Christina and Jeremy approached A24 and we were in production two months later. From the outside it seems like this dream scenario of having the incredible indie studios Plan B and A24 behind us, but the truth is it took years working on drafts and wondering if anyone would ever read them. I think the extra time we had helped, because if we had the chance to make it two or three years ago, I don’t think we would have been ready.

Jimmie Fails and the creative team behind ‘The Last Black Man in San Francisco’ at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. / Photo: Sue Peri

What was the first movie you made with Jimmie when you were teenagers?

The first half-decent thing we made was a movie that my brother and I co-directed called Last Stop Livermore. I am actually in it alongside Jimmie and that was my first and only time in front of the camera. I learned my place pretty early on.

Didn’t you have a cameo in Last Black Man? I swear I saw you.

I did have a cameo. As long as I’m not speaking, I’m okay. But even then when I just had to look at Jimmie once it was very difficult for me to do. I needed four takes for that shot, ha ha. I’m much more comfortable on the other side.

Jimmie, however, was really good in [Last Stop Livermore]. We made it while I was in high school before I dropped out, and it got into the San Francisco International Film Festival. Like everything we do, it’s based on something that happened in real life when a friend and I felt like we were fish out of water, going off to meet some girls in the suburbs.

That attention the film got, however minor, encouraged us because until that point only our family, friends and my high school teacher had seen our movies. Oh and Jimmie still had a flat-top—just thought I should add.

The film features the most important house of the year [Editor’s note: at least until the rest of the world sees the Parasite house, designed by the great Namgoong]. How did you find Jimmie’s house and what made it the house?

It took us over a year and a half to find the house. We combed the streets with my co-producer Luis Alfonso de la Parra and production designer Jona Tochet and knocked on doors. In hindsight, a more efficient way would have been to use Google Maps but this way we could see inside the houses.

Unfortunately, the interiors would usually be gutted and have IKEA furniture and granite table tops. As a filmmaker, it was depressing, but as a native San Franciscan it was heartbreaking because the details inside all these beautiful houses were destroyed. It’s a thing that a lot of real estate agents do when they flip houses.

We ended up going back to a house that I had driven past as a kid on my way to elementary school. My mom, my brother and I would pick out our dream Victorian houses on our family car ride since we couldn't afford a proper one. I went back to one of the houses that had always stuck with me. After we found that house, it felt like we had cast a major character in the movie.

When we first knocked on the door of the house that would become Jimmie's home in the film, an older gentlemen greeted us and within seconds beckoned us inside. As we entered, we found a home that had not been gutted, but instead had been lovingly restored. Jim, the homeowner, much like Jimmie, the actor, had spent more than half of his life working on the house.

He carved the witch hat you see in the movie shingle by shingle and did the honor of putting it on the roof himself. He fixed the organs you see in the film and built Pope's hole in the library. In many ways, he felt like the spirit of San Francisco.

As a now elderly man, we would have understood him declining our wants to film there -- or charging a buttload to help him in his retirement. Instead he welcomed our big crew into his house and charged us next to nothing. I still don't fully know why, but I can imagine he saw shades of himself in Jimmie's love for this Victorian.

In the years we spent location scouting, we would also meet people on the street that we put in the movie. Dakecia Chappell was working at a Whole Foods in the confectionery section, near a ‘potential Jimmie’s house’ around the corner and she was just really charming, so I offered her the ‘Candy Lady’ part in the film. We met the mover who tells Jimmie the homeowners are moving out late one night at a taqueria on Mission Street. This extra time allowed us to capture the little details of what our San Francisco is like.

Even after your major backing from Plan B and A24, was there a point on set where it felt like everything was falling apart?

I’m sure there are directors that aren’t plagued by the self-doubt I had. I didn’t go to film school and I felt isolated in San Francisco since a lot of the filmmakers have left for Los Angeles or New York. I was feeling this imposter syndrome. You’re both really joyous and grateful that you finally have a chance to make a movie, but also feel the weight of the city and wanting to honor what’s happening to people there. In every stage you have big and little freak-outs. The only thing that got me through it were the people around me. They bring perspective when you might not have it.

A couple of months before we shot the film my dad had a stroke. He survived, thankfully, and he would say half-jokingly “I survived to see the movie”. My parents struggled as artists themselves in their lives and yet they created this loving home that allowed us to make the movie. I look up to my Dad a lot, so when that happened that was really scary, and it happened during the height of the pandemonium of prep.

By that point our creative collaborators felt like family and they did everything for us. They came over to my house, brought us food, did as much as they could to take work off my plate so I could be with my own family. That always sticks with me when I remember tough times. You could say it’s just a job, but they treated it like so much more. So while it sounds corny, I think the spirit which comes with people being so loving and kind becomes imbued in the film.

Very glad to hear your dad is okay. The scenes with Jimmie’s parents are so powerful; you really get a greater sense of his isolation. It’s amazing his mom agreed to be in the film as a fictionalized version of herself. How did you and Jimmie sketch those scenes?

The scene with his mom is loosely based on something that happened. Jimmie was raised mostly by his dad and he’s very close to his parents now in a way that’s very different from the relationship that he had with them growing up. He and his dad have worked through a lot.

Jimmie Fails as Jimmie. This and the header photo are by Laila Bahman.

It’s hard to pack in all the complex details that makes someone who they are because you don’t have enough screen time to do that sometimes. These elements were pulled from the walks we’d take during the earliest developments when the idea was more informal and we’d talk about Jimmie’s family.

One story that Jimmie always recalled both humorously but also quite painfully was about the guy who had driven off in the car that he and his dad were living in at the time. We thought it would be funny if there was a character who never acknowledged that he’d stolen the car but claimed that he was still borrowing it. We knew Mike Epps would be the perfect person for that. It was a story that came from a kernel of truth but took on a life of its own.

Why was Jimmie’s dad pirating The Patriot, of all movies? The tonal juxtaposition made us laugh.

Ha ha, it was in the public domain.

We loved the score. What are some of the soundtracks that inspired you while making the film?

The Last of the Mohicans, The Day of the Dolphin, The Claim, Batman (and also the animated TV show’s score actually rivals Elfman’s), and Far From the Madding Crowd.

You’ve spoken in another interview about how you and Jimmie fear friendships like yours aren’t possible with the type of gentrification that’s going on. However, nowadays you can meet some of the important people in your life over the internet. Could the bonds we make online compensate for what’s being lost on the streets?

I think the internet is a double-edged sword. It both brings people together that you could never have met, such as how many of our closest collaborators first found our concept trailer online. But I do fear it also plays a part in people developing shallower, less intimate connections. I have friends who I love who will go to events seemingly just to get a good Instagram photo out of it. I’m sure I’ve suffered from similar instincts. That scares me.

Montgomery adds so much tenderness and insight to the film. Given he’s Jimmie’s best friend and he’s also an artist, is he your avatar in the movie? How did the casting of Jonathan Majors inform the development of his character?

Montgomery is actually not based on me. Jimmie and I have a friend from the Bay named Prentice Sanders who is one of the more original people we’ve ever met. His spirit influenced the first shades of the character. When Jon came on he took those early sketchings to a whole new level, creating his own backstory, mannerisms, and interests.

On the vanity in his room, Jon decided to put up Tennessee Williams, August Wilson, Barbara Stanwyck, Canada Lee, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison as inspiration. He had a hand in every little detail. In fact, Jon and Jimmie became very close in real life. They still talk nearly every day.

Warning: the last section of the interview contains spoilers, including for the endings of both ‘Last Black Man’ and ‘Ghost World’. This is your last chance to back out…

How do you direct Jimmie? I imagine you can read each other’s minds at this point.

Yeah, there is a weird unspoken connection between us, as we grew up together. Knowing each other for so long allowed us to be vulnerable around each other. As a director, inevitably there are days on set that are stressful, scary, and tense, so being able to go for a walk around the block together to recalibrate and feel present was helpful.

This film asked something much different than anything we had done before. We’d never written a feature script and most of our shorts were ad-libbed. Honestly, everyone broke their backs to make this. Cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra was a hero. Nobody phoned it in.

But more than anybody, we asked the most of Jimmie. There’s a scene where he’s across from his real mother and the bravery from both of them to do that set a tone that everyone on set sought to honor.

Joe Talbot and Jimmie Fails on the set of ‘The Last Black Man in San Francisco’. Photo by the film’s cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra.

Your collaboration with Jimmie has been so strong for such a long time. Is it a relief for you or maybe a sadness that this phase with him is nearly over?

It doesn’t feel like it’s over yet, but I’m sure when it does there will be a little bit of sadness. The movie continues to sell out theaters on a Wednesday afternoon in San Francisco and opened in the little neighborhood theaters that indies barely make it into and it's playing alongside Toy Story. There’s a feeling in the city now that’s hopeful.

It’s been wonderful to witness because I feel like we’ve been working through our feelings about San Francisco in making the movie, and in some ways Jimmie leaving at the end feels a bit like us, how perhaps we can’t be here anymore. I’ve only ever lived in San Francisco my entire life but maybe it is time to go somewhere else.

However, in putting the movie out there I’ve seen so many more natives that feel like people I grew up with 15-20 years ago. People who I thought had been lost but are still out there, fighting to exist somehow through all the changes. I feel like part of me is falling back in love with San Francisco again and I think that feeling is going to go on for a long time.

A lot of people are contacting us saying that they left the theater and they just started writing their own scripts, or writing poetry, or sending us paintings that were inspired by the movie. In a city that is increasingly difficult to exist in as an artist and not always inspiring, this always means something to us.

On the film’s ending: to you, where is Jimmie going?

Jimmie is going to start his legacy somewhere else—to fully be himself and start anew, following the footsteps of his grandfather. And it’s more fun to shoot it that way than have him ride away on a BART train.

One interpretation of the ending we’ve heard is that it was all in Mont’s head, and in “reality” it ended on a more tragic note. So some viewers felt it as hopeless, but you in fact intended it to be more hopeful?

I think we wanted to leave it open to interpretation. I talked to Thora Birch [who has a small role in Last Black Man] about the ending of Ghost World, because that always left an impression on me. I interpreted it as a suicide when I saw it as a teenager and she had told me that she felt that way about it too, but there are also people who thought she was going off to art school. I feel our ending works in the same way.

I don’t see any interpretation of it as invalid, but what your relationship is to your city affects what you bring to it. Either way it’s a bittersweet ending, because it is a loss for Jimmie and Mont’s friendship, and for the city. Like, San Francisco doesn’t deserve him anymore.

Discover the films that inspired the look and feel of ‘The Last Black Man in San Francisco’.

#the last black man in san francisco#joe talbot#jimmie fails#danny glover#san franciso bay#gentrification#sundance#sundance2019#letterboxd

13 notes

·

View notes