#i keep my anonymity on here mostly due to how many past coworkers have been written up and fired for talking about the job online lol

Note

Customer service ain’t for the weak. And I’m weak as fuck.

THIS. AFTER THE SHIFT I JUST HAD, THIS HAS ME ROLLING. the way i am biting my tongue so hard because i know the siren is always watching 💀

#i keep my anonymity on here mostly due to how many past coworkers have been written up and fired for talking about the job online lol#also because my major involved me going into a career where it might be best i stay anonymous#but i’m also 10 seconds away from quitting#especially after today 😀#this made my day boom thank you 😭😭🖤#boom <3#me and the lady from this morning when i had just gotten on shift are about to go rounds i wish i had said something like that to her#want a refund? go get it. 😐#i wasn’t having it today but i didn’t get in trouble 😭😭 so

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Food Is No Longer Your Fallback Job. It Never Should Have Been in the First Place.

Barista | Shutterstock

It’s time we stop considering these jobs as a backup and start providing dignity to all workers

I graduated from college in the spring of 2008. If you’ll recall, that fall wasn’t a great time to enter the job market, and the advice I got from anyone who had an opinion (which was everyone) was to “go wait tables.” It was a catchall phrase for the kind of work that was assumed to be available whenever the chips were down — the guidance given to every high schooler looking for extra money, every college grad who doesn’t have a job lined up, every aspiring actor in LA. And even at that time, when the unemployment rate was somewhere around 10 percent, it was available: I got a job as a hostess and server at a local restaurant, but I also had an offer from Starbucks, and an invitation to return to work at a bakery I’d worked at the previous summer.

Once again, we’re facing a recession, or, according to some experts, a full-on depression. Unemployment websites crashed as millions have applied for benefits in the past weeks, and food banks can’t keep up with demand — one-third of those going to them for food have never needed aid before. The coronavirus pandemic has revealed basically every fault line in our society, from the inadequacy of the social safety net to the incompetence of many of our leaders. And it is now revealing some long-held assumptions about work in the food-service industry. Being a server, a bartender, or a dishwasher, or doing other restaurant work, is often spoken of as a job that is always — and implicitly, only — viable when there are no other options. That if anyone had a real choice, they would choose something else. But because restaurants and bars aren’t hiring, food is no longer the fallback job. It never should have been thought of in that way in the first place.

The restaurant industry has long been the province of outcasts, but over the last two decades, owning a restaurant, becoming a celebrity(ish) chef, and, to a certain extent, being a fancy mixologist have come to be considered actual careers. These are the kinds of jobs that can land you a steady paycheck and the status of “small-business owner,” or even book deals and TV appearances. But when you’re not the owner or the creative force behind the food, food service — from hustling shifts as a server to manning the cash register at McDonald’s — is still generally talked about as a temporary detour, a place to lay low while you get your shit together. In pop culture, it’s an after-school job for teens, even though only about 30 percent of fast-food workers are teenagers. The mainstream image is still a job you leave, not one you keep.

“It’s an industry many fall back on time and time again,” writes Frances Bridges for Forbes. In 2011, Brokelyn told recent college grads that they likely “will consider waiting tables as a fallback to your day-job dreams,” the assumption being that everyone dreams of a day job. In 2016, Forbes called being a host or bartender one of the best jobs to have “while you are figuring out what to do with your life,” as it provides both a steady paycheck and, due to high turnover, restaurants and bars are “almost always hiring.” The assumption by economists and career experts was that no matter what, people need to eat, and they would want to eat out — so restaurant work would always be around.

Now, for the first time, it’s not. Nearly every state has issued orders for restaurants to close dine-in options or severely reduce capacity, forcing restaurants to lay off or furlough workers — or shutter entirely. About 10 million people filed for unemployment in the past few weeks, a number that’s expected to keep rising by the millions. And that number doesn’t account for gig-economy workers — like Instacart couriers or Uber Eats drivers — who, as contractors, wouldn’t qualify for UI. The food-service industry was hit particularly hard. According to the Department of Labor, restaurant and bar jobs accounted for 60 percent of the jobs lost in March. It’s clear that serving food and making drinks is not the revolving door it has been made out to be.

Jennifer Cathey, a former line cook at Glory World Gyro in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, says the restaurant has tried to stay open for takeout and delivery services, but there’s almost no business, and she was often “alone in a kitchen for hours at a time.” After a week, she volunteered to be laid off, as she lives with her mother and doesn’t need the money for rent. “If work was going to be so slow, it didn’t feel right to take any of the meager hours given to employees for any of my other coworkers,” she told Eater.

Cathey, who started working in her mother’s restaurant as a teenager, says she wanted to sacrifice her shifts for her coworkers because the food industry has always felt like home for her. “It is my favorite kind of work, I’ve loved all the places I’ve worked,” she says. Mostly it’s because she gets the immediate gratification of making something for someone else to consume and enjoy. But it’s also because, as a trans woman, the restaurant industry is a place she can rely on to be welcoming. “Especially living here in Alabama, all the people I’ve met through the restaurant and bar industries have been the most accepting of anyone,” she says. “I might not get anyone from my hometown to call me by my name, but the food-service community is tight-knit and open and welcome to all sorts of people... I have that fear that other industries wouldn’t be as welcoming.”

Unfortunately, it is also because food service has been a space for those who don’t fit into other parts of society that it has been considered a job for those who just need a job. Food service doesn’t require a college degree (or even a high school diploma), and it’s traditionally more welcoming to those with criminal backgrounds, to immigrants, to queer people, and to those with little other work experience. In Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain referred to line cooks as a “dysfunctional, mercenary lot” and “fringe dwellers.” Not the most generous reading, but one that speaks to the reality: that in most people’s opinion, any office job is preferable to a career in the restaurant industry.

Which is not to say it’s not worthy work. If this pandemic has proven anything, it’s how essential those working in the food industry are. Instead, these assumptions come from a cycle of low pay and bad benefits that devalue both the job itself and the people doing it. “It’s set up to be temporary,” says Lauren* (who asked to remain anonymous), who was recently laid off from her bartending job at Dock Street Brewery in Philadelphia. “There are minimal benefits, pay increases, or opportunities for moving up in a company. And then this happens, and it makes it even more apparent how the industry is set up to be temporary, even though the people working in it don’t see it that way.”

A “reasonable” person, says the strawman I’ve invented but also probably plenty of people you’ve actually met, wouldn’t choose to make a career out of a job that relies on tips, that doesn’t provide health insurance, and where one risks such injury. Thus, the people who choose this career must not be “reasonable,” and if that’s true, then why support such unreasonable people? And on and on.

If it were true that food service is only a paycheck for those who are waiting for their “real” career to appear, then presumably no one would care one way or another about the job itself. But multiple people I talked to spoke of the restaurant industry — waiting tables, working the line, making lattes — as their dream job. “I literally emailed Pizzana for two years until they gave me a shot,” says Will Weissman, who was recently laid off from the West Hollywood pizza restaurant. He loved the restaurant’s food from the first time he tasted it, and hoped when they opened a second location, they’d take a chance on him, even though he had no previous experience. “I had always been food obsessed. I know a lot about wine, I’m a good cook, and I just wanted to finally do something in the food industry.”

Samantha Ortiz, a chef at Kingsbridge Social Club in the Bronx, says she was instantly drawn to the hospitality industry when she started work as a barista. “I felt so fulfilled to be able to make something for someone, even if it was as simple as a latte,” she says. Now, her restaurant is closed and her unemployment will run out in 90 days, but she has no plans to switch industries. “I doubt that I would ever look for a job in a different field,” she says. “The kitchen is home.”

When my serving job ended (the restaurant shut down), I was slightly relieved. I was a terrible server, and I knew I had other options. But many of my coworkers expressed deeper laments. They liked the strong arms they got from carrying trays of food, and they enjoyed recommending a dish and hearing their customer loved it. They liked that each night was different and experimenting with making new drinks. Hearing from them, I understood that the restaurant’s closure was a loss.

It’s not quite true that there are no food-service jobs available right now. Instead of the serving jobs that college grads are urged to consider, there’s a new form of food work that’s thriving during this recession: the gig worker. Grocery stores and apps like Instacart are hiring deliverers and baggers by the thousands. It’s mostly temporary work, and puts workers at higher risk for contagion, but it’s there. In a vacuum, there’s a lot to love about a job as a gig-economy deliverer. Setting one’s own schedule, picking up shifts when it’s convenient, providing a necessary service to people who can’t travel or carry their own groceries — that’s a good job. What’s not good is the pay, the exploitation, the hundred ways these corporations leech off their workers and make it impossible to make a living wage. But that doesn’t have to be the case.

We as a society have set these jobs up to be temporary, so when someone wants to make their job permanent, we think it is a failure on their part, rather than a failure on ours. There is no such thing as a “bad” job, only bad conditions. Food-service work doesn’t have to be low paid. It doesn’t have to rely on tips, or come without health care or paid sick leave. In the face of the pandemic, we’re seeing how that is the case, as grocery stores and delivery services are pressured into providing better benefits and pay to these essential workers. But it’s time we stop considering these jobs, any jobs, as backup, and time to start providing dignity to all workers.

“It’s hard seeing people that I really care about, that I work with, be treated as disposable,” says Lauren. “I definitely go back and forth every day being like, ‘Is this even worth it, or am I just pouring all of my energy into continuing to be treated really poorly?’ I don’t know.”

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/34nd7lE

https://ift.tt/2VagA2E

Barista | Shutterstock

It’s time we stop considering these jobs as a backup and start providing dignity to all workers

I graduated from college in the spring of 2008. If you’ll recall, that fall wasn’t a great time to enter the job market, and the advice I got from anyone who had an opinion (which was everyone) was to “go wait tables.” It was a catchall phrase for the kind of work that was assumed to be available whenever the chips were down — the guidance given to every high schooler looking for extra money, every college grad who doesn’t have a job lined up, every aspiring actor in LA. And even at that time, when the unemployment rate was somewhere around 10 percent, it was available: I got a job as a hostess and server at a local restaurant, but I also had an offer from Starbucks, and an invitation to return to work at a bakery I’d worked at the previous summer.

Once again, we’re facing a recession, or, according to some experts, a full-on depression. Unemployment websites crashed as millions have applied for benefits in the past weeks, and food banks can’t keep up with demand — one-third of those going to them for food have never needed aid before. The coronavirus pandemic has revealed basically every fault line in our society, from the inadequacy of the social safety net to the incompetence of many of our leaders. And it is now revealing some long-held assumptions about work in the food-service industry. Being a server, a bartender, or a dishwasher, or doing other restaurant work, is often spoken of as a job that is always — and implicitly, only — viable when there are no other options. That if anyone had a real choice, they would choose something else. But because restaurants and bars aren’t hiring, food is no longer the fallback job. It never should have been thought of in that way in the first place.

The restaurant industry has long been the province of outcasts, but over the last two decades, owning a restaurant, becoming a celebrity(ish) chef, and, to a certain extent, being a fancy mixologist have come to be considered actual careers. These are the kinds of jobs that can land you a steady paycheck and the status of “small-business owner,” or even book deals and TV appearances. But when you’re not the owner or the creative force behind the food, food service — from hustling shifts as a server to manning the cash register at McDonald’s — is still generally talked about as a temporary detour, a place to lay low while you get your shit together. In pop culture, it’s an after-school job for teens, even though only about 30 percent of fast-food workers are teenagers. The mainstream image is still a job you leave, not one you keep.

“It’s an industry many fall back on time and time again,” writes Frances Bridges for Forbes. In 2011, Brokelyn told recent college grads that they likely “will consider waiting tables as a fallback to your day-job dreams,” the assumption being that everyone dreams of a day job. In 2016, Forbes called being a host or bartender one of the best jobs to have “while you are figuring out what to do with your life,” as it provides both a steady paycheck and, due to high turnover, restaurants and bars are “almost always hiring.” The assumption by economists and career experts was that no matter what, people need to eat, and they would want to eat out — so restaurant work would always be around.

Now, for the first time, it’s not. Nearly every state has issued orders for restaurants to close dine-in options or severely reduce capacity, forcing restaurants to lay off or furlough workers — or shutter entirely. About 10 million people filed for unemployment in the past few weeks, a number that’s expected to keep rising by the millions. And that number doesn’t account for gig-economy workers — like Instacart couriers or Uber Eats drivers — who, as contractors, wouldn’t qualify for UI. The food-service industry was hit particularly hard. According to the Department of Labor, restaurant and bar jobs accounted for 60 percent of the jobs lost in March. It’s clear that serving food and making drinks is not the revolving door it has been made out to be.

Jennifer Cathey, a former line cook at Glory World Gyro in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, says the restaurant has tried to stay open for takeout and delivery services, but there’s almost no business, and she was often “alone in a kitchen for hours at a time.” After a week, she volunteered to be laid off, as she lives with her mother and doesn’t need the money for rent. “If work was going to be so slow, it didn’t feel right to take any of the meager hours given to employees for any of my other coworkers,” she told Eater.

Cathey, who started working in her mother’s restaurant as a teenager, says she wanted to sacrifice her shifts for her coworkers because the food industry has always felt like home for her. “It is my favorite kind of work, I’ve loved all the places I’ve worked,” she says. Mostly it’s because she gets the immediate gratification of making something for someone else to consume and enjoy. But it’s also because, as a trans woman, the restaurant industry is a place she can rely on to be welcoming. “Especially living here in Alabama, all the people I’ve met through the restaurant and bar industries have been the most accepting of anyone,” she says. “I might not get anyone from my hometown to call me by my name, but the food-service community is tight-knit and open and welcome to all sorts of people... I have that fear that other industries wouldn’t be as welcoming.”

Unfortunately, it is also because food service has been a space for those who don’t fit into other parts of society that it has been considered a job for those who just need a job. Food service doesn’t require a college degree (or even a high school diploma), and it’s traditionally more welcoming to those with criminal backgrounds, to immigrants, to queer people, and to those with little other work experience. In Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain referred to line cooks as a “dysfunctional, mercenary lot” and “fringe dwellers.” Not the most generous reading, but one that speaks to the reality: that in most people’s opinion, any office job is preferable to a career in the restaurant industry.

Which is not to say it’s not worthy work. If this pandemic has proven anything, it’s how essential those working in the food industry are. Instead, these assumptions come from a cycle of low pay and bad benefits that devalue both the job itself and the people doing it. “It’s set up to be temporary,” says Lauren* (who asked to remain anonymous), who was recently laid off from her bartending job at Dock Street Brewery in Philadelphia. “There are minimal benefits, pay increases, or opportunities for moving up in a company. And then this happens, and it makes it even more apparent how the industry is set up to be temporary, even though the people working in it don’t see it that way.”

A “reasonable” person, says the strawman I’ve invented but also probably plenty of people you’ve actually met, wouldn’t choose to make a career out of a job that relies on tips, that doesn’t provide health insurance, and where one risks such injury. Thus, the people who choose this career must not be “reasonable,” and if that’s true, then why support such unreasonable people? And on and on.

If it were true that food service is only a paycheck for those who are waiting for their “real” career to appear, then presumably no one would care one way or another about the job itself. But multiple people I talked to spoke of the restaurant industry — waiting tables, working the line, making lattes — as their dream job. “I literally emailed Pizzana for two years until they gave me a shot,” says Will Weissman, who was recently laid off from the West Hollywood pizza restaurant. He loved the restaurant’s food from the first time he tasted it, and hoped when they opened a second location, they’d take a chance on him, even though he had no previous experience. “I had always been food obsessed. I know a lot about wine, I’m a good cook, and I just wanted to finally do something in the food industry.”

Samantha Ortiz, a chef at Kingsbridge Social Club in the Bronx, says she was instantly drawn to the hospitality industry when she started work as a barista. “I felt so fulfilled to be able to make something for someone, even if it was as simple as a latte,” she says. Now, her restaurant is closed and her unemployment will run out in 90 days, but she has no plans to switch industries. “I doubt that I would ever look for a job in a different field,” she says. “The kitchen is home.”

When my serving job ended (the restaurant shut down), I was slightly relieved. I was a terrible server, and I knew I had other options. But many of my coworkers expressed deeper laments. They liked the strong arms they got from carrying trays of food, and they enjoyed recommending a dish and hearing their customer loved it. They liked that each night was different and experimenting with making new drinks. Hearing from them, I understood that the restaurant’s closure was a loss.

It’s not quite true that there are no food-service jobs available right now. Instead of the serving jobs that college grads are urged to consider, there’s a new form of food work that’s thriving during this recession: the gig worker. Grocery stores and apps like Instacart are hiring deliverers and baggers by the thousands. It’s mostly temporary work, and puts workers at higher risk for contagion, but it’s there. In a vacuum, there’s a lot to love about a job as a gig-economy deliverer. Setting one’s own schedule, picking up shifts when it’s convenient, providing a necessary service to people who can’t travel or carry their own groceries — that’s a good job. What’s not good is the pay, the exploitation, the hundred ways these corporations leech off their workers and make it impossible to make a living wage. But that doesn’t have to be the case.

We as a society have set these jobs up to be temporary, so when someone wants to make their job permanent, we think it is a failure on their part, rather than a failure on ours. There is no such thing as a “bad” job, only bad conditions. Food-service work doesn’t have to be low paid. It doesn’t have to rely on tips, or come without health care or paid sick leave. In the face of the pandemic, we’re seeing how that is the case, as grocery stores and delivery services are pressured into providing better benefits and pay to these essential workers. But it’s time we stop considering these jobs, any jobs, as backup, and time to start providing dignity to all workers.

“It’s hard seeing people that I really care about, that I work with, be treated as disposable,” says Lauren. “I definitely go back and forth every day being like, ‘Is this even worth it, or am I just pouring all of my energy into continuing to be treated really poorly?’ I don’t know.”

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/34nd7lE

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2XpvFQY

0 notes

Text

Food Is No Longer Your Fallback Job. It Never Should Have Been in the First Place. added to Google Docs

Food Is No Longer Your Fallback Job. It Never Should Have Been in the First Place.

Barista | Shutterstock

It’s time we stop considering these jobs as a backup and start providing dignity to all workers

I graduated from college in the spring of 2008. If you’ll recall, that fall wasn’t a great time to enter the job market, and the advice I got from anyone who had an opinion (which was everyone) was to “go wait tables.” It was a catchall phrase for the kind of work that was assumed to be available whenever the chips were down — the guidance given to every high schooler looking for extra money, every college grad who doesn’t have a job lined up, every aspiring actor in LA. And even at that time, when the unemployment rate was somewhere around 10 percent, it was available: I got a job as a hostess and server at a local restaurant, but I also had an offer from Starbucks, and an invitation to return to work at a bakery I’d worked at the previous summer.

Once again, we’re facing a recession, or, according to some experts, a full-on depression. Unemployment websites crashed as millions have applied for benefits in the past weeks, and food banks can’t keep up with demand — one-third of those going to them for food have never needed aid before. The coronavirus pandemic has revealed basically every fault line in our society, from the inadequacy of the social safety net to the incompetence of many of our leaders. And it is now revealing some long-held assumptions about work in the food-service industry. Being a server, a bartender, or a dishwasher, or doing other restaurant work, is often spoken of as a job that is always — and implicitly, only — viable when there are no other options. That if anyone had a real choice, they would choose something else. But because restaurants and bars aren’t hiring, food is no longer the fallback job. It never should have been thought of in that way in the first place.

The restaurant industry has long been the province of outcasts, but over the last two decades, owning a restaurant, becoming a celebrity(ish) chef, and, to a certain extent, being a fancy mixologist have come to be considered actual careers. These are the kinds of jobs that can land you a steady paycheck and the status of “small-business owner,” or even book deals and TV appearances. But when you’re not the owner or the creative force behind the food, food service — from hustling shifts as a server to manning the cash register at McDonald’s — is still generally talked about as a temporary detour, a place to lay low while you get your shit together. In pop culture, it’s an after-school job for teens, even though only about 30 percent of fast-food workers are teenagers. The mainstream image is still a job you leave, not one you keep.

“It’s an industry many fall back on time and time again,” writes Frances Bridges for Forbes. In 2011, Brokelyn told recent college grads that they likely “will consider waiting tables as a fallback to your day-job dreams,” the assumption being that everyone dreams of a day job. In 2016, Forbes called being a host or bartender one of the best jobs to have “while you are figuring out what to do with your life,” as it provides both a steady paycheck and, due to high turnover, restaurants and bars are “almost always hiring.” The assumption by economists and career experts was that no matter what, people need to eat, and they would want to eat out — so restaurant work would always be around.

Now, for the first time, it’s not. Nearly every state has issued orders for restaurants to close dine-in options or severely reduce capacity, forcing restaurants to lay off or furlough workers — or shutter entirely. About 10 million people filed for unemployment in the past few weeks, a number that’s expected to keep rising by the millions. And that number doesn’t account for gig-economy workers — like Instacart couriers or Uber Eats drivers — who, as contractors, wouldn’t qualify for UI. The food-service industry was hit particularly hard. According to the Department of Labor, restaurant and bar jobs accounted for 60 percent of the jobs lost in March. It’s clear that serving food and making drinks is not the revolving door it has been made out to be.

Jennifer Cathey, a former line cook at Glory World Gyro in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, says the restaurant has tried to stay open for takeout and delivery services, but there’s almost no business, and she was often “alone in a kitchen for hours at a time.” After a week, she volunteered to be laid off, as she lives with her mother and doesn’t need the money for rent. “If work was going to be so slow, it didn’t feel right to take any of the meager hours given to employees for any of my other coworkers,” she told Eater.

Cathey, who started working in her mother’s restaurant as a teenager, says she wanted to sacrifice her shifts for her coworkers because the food industry has always felt like home for her. “It is my favorite kind of work, I’ve loved all the places I’ve worked,” she says. Mostly it’s because she gets the immediate gratification of making something for someone else to consume and enjoy. But it’s also because, as a trans woman, the restaurant industry is a place she can rely on to be welcoming. “Especially living here in Alabama, all the people I’ve met through the restaurant and bar industries have been the most accepting of anyone,” she says. “I might not get anyone from my hometown to call me by my name, but the food-service community is tight-knit and open and welcome to all sorts of people... I have that fear that other industries wouldn’t be as welcoming.”

Unfortunately, it is also because food service has been a space for those who don’t fit into other parts of society that it has been considered a job for those who just need a job. Food service doesn’t require a college degree (or even a high school diploma), and it’s traditionally more welcoming to those with criminal backgrounds, to immigrants, to queer people, and to those with little other work experience. In Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain referred to line cooks as a “dysfunctional, mercenary lot” and “fringe dwellers.” Not the most generous reading, but one that speaks to the reality: that in most people’s opinion, any office job is preferable to a career in the restaurant industry.

Which is not to say it’s not worthy work. If this pandemic has proven anything, it’s how essential those working in the food industry are. Instead, these assumptions come from a cycle of low pay and bad benefits that devalue both the job itself and the people doing it. “It’s set up to be temporary,” says Lauren* (who asked to remain anonymous), who was recently laid off from her bartending job at Dock Street Brewery in Philadelphia. “There are minimal benefits, pay increases, or opportunities for moving up in a company. And then this happens, and it makes it even more apparent how the industry is set up to be temporary, even though the people working in it don’t see it that way.”

A “reasonable” person, says the strawman I’ve invented but also probably plenty of people you’ve actually met, wouldn’t choose to make a career out of a job that relies on tips, that doesn’t provide health insurance, and where one risks such injury. Thus, the people who choose this career must not be “reasonable,” and if that’s true, then why support such unreasonable people? And on and on.

If it were true that food service is only a paycheck for those who are waiting for their “real” career to appear, then presumably no one would care one way or another about the job itself. But multiple people I talked to spoke of the restaurant industry — waiting tables, working the line, making lattes — as their dream job. “I literally emailed Pizzana for two years until they gave me a shot,” says Will Weissman, who was recently laid off from the West Hollywood pizza restaurant. He loved the restaurant’s food from the first time he tasted it, and hoped when they opened a second location, they’d take a chance on him, even though he had no previous experience. “I had always been food obsessed. I know a lot about wine, I’m a good cook, and I just wanted to finally do something in the food industry.”

Samantha Ortiz, a chef at Kingsbridge Social Club in the Bronx, says she was instantly drawn to the hospitality industry when she started work as a barista. “I felt so fulfilled to be able to make something for someone, even if it was as simple as a latte,” she says. Now, her restaurant is closed and her unemployment will run out in 90 days, but she has no plans to switch industries. “I doubt that I would ever look for a job in a different field,” she says. “The kitchen is home.”

When my serving job ended (the restaurant shut down), I was slightly relieved. I was a terrible server, and I knew I had other options. But many of my coworkers expressed deeper laments. They liked the strong arms they got from carrying trays of food, and they enjoyed recommending a dish and hearing their customer loved it. They liked that each night was different and experimenting with making new drinks. Hearing from them, I understood that the restaurant’s closure was a loss.

It’s not quite true that there are no food-service jobs available right now. Instead of the serving jobs that college grads are urged to consider, there’s a new form of food work that’s thriving during this recession: the gig worker. Grocery stores and apps like Instacart are hiring deliverers and baggers by the thousands. It’s mostly temporary work, and puts workers at higher risk for contagion, but it’s there. In a vacuum, there’s a lot to love about a job as a gig-economy deliverer. Setting one’s own schedule, picking up shifts when it’s convenient, providing a necessary service to people who can’t travel or carry their own groceries — that’s a good job. What’s not good is the pay, the exploitation, the hundred ways these corporations leech off their workers and make it impossible to make a living wage. But that doesn’t have to be the case.

We as a society have set these jobs up to be temporary, so when someone wants to make their job permanent, we think it is a failure on their part, rather than a failure on ours. There is no such thing as a “bad” job, only bad conditions. Food-service work doesn’t have to be low paid. It doesn’t have to rely on tips, or come without health care or paid sick leave. In the face of the pandemic, we’re seeing how that is the case, as grocery stores and delivery services are pressured into providing better benefits and pay to these essential workers. But it’s time we stop considering these jobs, any jobs, as backup, and time to start providing dignity to all workers.

“It’s hard seeing people that I really care about, that I work with, be treated as disposable,” says Lauren. “I definitely go back and forth every day being like, ‘Is this even worth it, or am I just pouring all of my energy into continuing to be treated really poorly?’ I don’t know.”

via Eater - All https://www.eater.com/2020/4/9/21213573/restaurant-workers-temporary-food-industry-fallback-job

Created April 10, 2020 at 02:12AM

/huong sen

View Google Doc Nhà hàng Hương Sen chuyên buffet hải sản cao cấp✅ Tổ chức tiệc cưới✅ Hội nghị, hội thảo✅ Tiệc lưu động✅ Sự kiện mang tầm cỡ quốc gia 52 Phố Miếu Đầm, Mễ Trì, Nam Từ Liêm, Hà Nội http://huongsen.vn/ 0904988999 http://huongsen.vn/to-chuc-tiec-hoi-nghi/ https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1xa6sRugRZk4MDSyctcqusGYBv1lXYkrF

0 notes

Text

The Texas Frightmare Weekend Official Group on Facebook isn’t just a place for attendees to talk about the convention, but a place where the Texas Frightmare family can be themselves.

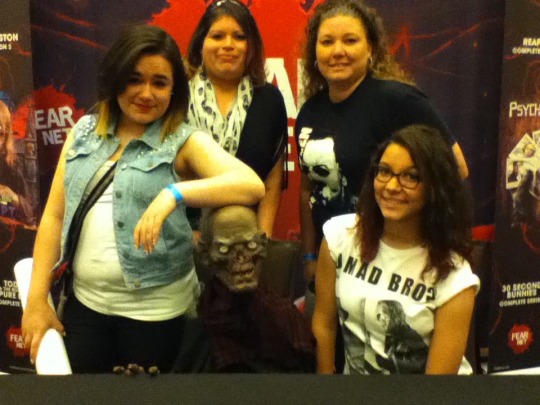

I have been a lifelong horror fan, and that love of horror was inherited by my mom. We have always loved watching scary movies, and going all out for Halloween. Around my junior or senior year of high school, one of my mom’s coworkers told her about a local horror convention, Texas Frightmare Weekend. Texas Frightmare is an annual horror convention held in Dallas, Texas during the first weekend of May. Before learning of this convention, I didn’t really know much of anything about conventions, and what happens at them. When we found out about Texas Frightmare we started following their Facebook page to learn more about the event. Texas Frightmare, and other pop culture conventions, usually involve celebrity guests that sign autographs and have photo ops, as well as vendors that sell all sorts of merch aimed toward whatever type of pop culture the convention is for, so in this case, horror. In 2013, we decided to go to our first Texas Frightmare Weekend with a couple of our friends and soon found out that the convention sphere is much more than what it looks like it is online, it’s a world of its own.

We ended up having a blast at the convention. The atmosphere was very fun and inviting, unlike any other event or place we've been to before. None of us had ever been so close to so many other people who loved the horror genre as we did. After attending Texas Frightmare that year, we started following them more closely online and really threw ourselves into that world. People would share their photos from the convention, stories, questions, and their dream guests/requests for who they wish would attend the following year onto Texas Frightmare’s Facebook wall, and this continued to happen year-round, not just immediately prior to and after the convention. It was clear that Texas Frightmare attendees loved the company of each other, and making new friends, I even made one of my best friends through Texas Frightmare’s Facebook page! Really, the community considered each other more than friends, they’re a family.

Finally, in 2017, the showrunner of Texas Frightmare, Loyd Cryer, decided to create a Facebook group for the Texas Frightmare family to join and post in. The group made it much easier to communicate with the fellow attendees/family members that you didn’t. Instead of going to Texas Frightmare’s Facebook page and having conversations on their posts, or going to the visitor posts tab to see other people’s posts on the page, or make your own, all you had to do was go to the Texas Frightmare Weekend Official Group.

Like every group, online or not, this group had rules, both written and unspoken. There are six written rules of the Texas Frightmare Weekend Official Group that were written by the admins. One, “Please no guest requests here… in an effort to keep the page clear for important info that will help attendees navigate the event”. At first, they were allowed, but due to them consuming the group, this rule was made and all posts have to be reviewed and approved by an admin before they are actually posted. Two, “search the group before posting anything”, ie: questions, and concerns that may have already been answered in another post. Three, ‘No posts about ticket or hotel sales or transfers”. Four, “Be Kind and Courteous”. This rule goes beyond the written rules, and into the unspoken ones as well. The admins just want everyone to be respectful of each other, but as I’ve said before, the group takes it to the next level by treating everyone like family, even if you’ve never talked to them before. I find this to be that in mainstream society, horror lovers are largely viewed as “freaks” and “outcasts” and put down by others, so we want to make the community extra welcoming, and not add on to this by berating each other further. I believe that the group taking place on Facebook, which is a social platform that is very personal and lacks anonymity also contributes to the increase of kind behavior between the members. The fifth rule is “no promotions or spam/no for sale posts”. The sixth and final rule is “no posts or comments about other events”, you wouldn’t go into a Denny’s and spend your whole time there talking about IHOP, would you?

Historically, society views the horror genre as something mainly for the boys, so most people assume that there are more male horror fans than there are female ones. The site I write for, The Horror Syndicate’s Facebook statistics supports this, showing that our followers are 64% male, and 36% female. However, data from Movio in 2017 showed that 53% of horror fans are female, so clearly the numbers can vary. With the Texas Frightmare Official Facebook Group, if you scroll through the list of members, it appears that most of them are male, however, most of the people who are actually posting in the group are female. Other statistics on horror fans from Nielson’s 2015 data say that the average consumer of horror tends to be between the ages of 35 and 44. Through my participation in the Texas Frightmare Facebook group, it seems like the people within this group are also within this age range, but extends to people in their 20s, like myself, as well.

As far as the economic class of the members of the Texas Frightmare facebook group goes, there are pretty much people from every class, ranging from upper lower class to the upper class. Since the biggest common factor everyone in the group has is that they attend Texas Frightmare, this is the first thing I took into consideration when determining the class makeup of the members. The convention itself is fairly cheap to attend. Passes start as low as $20 depending on how early you buy them, and how many days of the convention you want to attend, so low-income families, like my own and friends I’ve gone with, can afford to attend. Even most of the merchandise sold by vendors are reasonably priced, but it starts to get pricey when you add up the autographs and photo ops from the guests that can cost hundreds of dollars each. While we typically go and only buy a few things from a couple of vendors, or save up over the year in order to afford a picture with one of our favorite horror actors, many people go to the convention and spend hundreds, or even thousands on VIP passes, hotel rooms, and collectibles. Some people even travel from other countries to attend Texas Frightmare.

I’ve been a member of the Texas Frightmare Official Facebook Group since the day it was made in October of 2017, but I seldom post or even browse it, simply because I just don’t use Facebook in general very often. The few times I have posted in it, prior to the past month, was either when the convention was around the corner or the day of the convention. A year or so ago I remember asking if anyone who was going to the convention would be coming from the exact city I live in, or passing through on their way, attempting to find someone to carpool with. The Texas Frightmare family was very responsive to that post, and I got many offers to help.

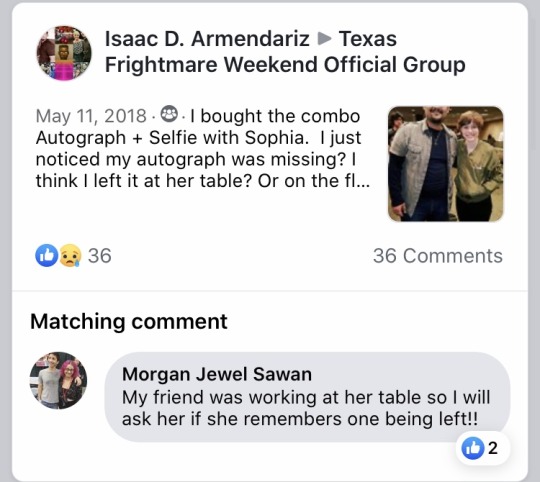

I also typically post pictures of cosplay I wear to the convention. I do really enjoy scrolling through the group after the convention is over to see everybody’s pictures, and hauls from the weekend. One memory that sticks out is when someone had posted about losing an autograph they bought at the convention. Many people were commenting on the post, trying to help the person out, showing once again how tightly knit and loving the group is. I actually ended up helping the attendee be reunited with their autograph because my friend was working at that specific guest’s table, so I showed her the post and she had the autograph and was able to send it back to the person who lost it.

When it’s not convention season, the group is still very active, and the post in it consists of articles about horror movies, pictures of personal horror collections, but mostly, the group is full of horror-related memes. I’ve come to the conclusion that this is the case because the poster may not feel comfortable sharing the memes on their timeline, knowing that their Facebook friends who aren’t into horror wouldn’t understand them, or even worse, would judge them negatively for it. When someone shares one of these funny memes to the group it’s usually just a reshare of it from another page, and the poster typically doesn’t insert their own caption on their share of it. These posts don’t warrant much discussion, but they do get tons of likes, love, laugh, and wow reacts. Other types of posts, such as personal pictures or stories, or ones that share articles do tend to get more comments, but less reacts and attention in general.

During the month of October, I figured that the amount of activity in the group might go up a little bit, due to the holiday season. I did see more posts from people showing off their Halloween costumes, and decorations. I kept my posts for the month on theme as well. In a prior Viral Content class, I learned that people interact with posts that make them feel strong emotions, like happiness from the funny memes, or if they feel like they’re getting something out of it. For instance, people are more likely to start a conversation if they are prompted to through a question or poll, so this is what I decided to do in one post, by asking what everyone’s Halloween costumes were going to be, and then saying what the ones I had planned were. In this post, I got a fairly decent response, with only two likes, but 12 comments from people sharing their costumes.

Posts with media typically get more attention than posts with just texts, since the image or video with the post catches the attention of people scrolling through Facebook more easily. So for the next post, I decided to post pictures of my costumes, as well as ask what everyone’s Halloween plans were in the text portion, in an attempt to get more people to react AND comment on the post. While my pictures did catch more people’s attention, making the post get 56 reactions, only six people commented on the post, leading me to believe that most people only looked at the pictures, and didn’t read the text.

From my posts in the group this month, I learned that the group is filled with tons of creative people. Most of the people that commented on my post asking about costumes were creating their own costumes. While part of me is not surprised by this, since there are a large number of attendees who go to the convention in cosplay, I am still shocked. Scrolling through the group, you will see the occasional post of someone’s horror art as well. When thinking about these facts, I wondered if the members of the group mainly use their creativity as a hobby, or if it’s incorporated into what they do for a living. If you look at the list of members of the group, you can conclude that a large portion of the group does the latter. It seemed like every other person in the group had their job listed as something that involves being creative. From artists, graphic designers, writers, filmmakers, and more. Many members have a career that doesn’t only involve creativity, but the horror genre as well.

Through my time spent analyzing the group, and the horror community as a whole, it’s clear that the members of the Texas Frightmare Official Group on Facebook, take their love of horror, and others who love horror as well, to the next level.

Sources Cited

“Frightful Fans: The Profile of Horror Movie Lovers.” What People Watch, Listen To and Buy, www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2015/frightful-fans-the-profile-of-horror-movie-lovers.html.

Palmer, Will. “CinemaCon 2017: Who Is Your Audience in 2017?” Box Office Pro, 29 Mar. 2017, pro.boxoffice.com/who-is-your-audience-in-2017/

“The Horror Syndicate Facebook Demographics.” Facebook, www.facebook.com/horrorsyndicate/insights/?section=navPeople

Picture

Sawan, Morgan. “My first Texas Frightmare”, May 5, 2013

Sawan, Morgan. “Screenshot of Texas Frightmare Haul”, Druin II, Roger. November 10, 2019

Sawan, Morgan. “Screenshot of Lost Autograph”,D. Armendariz, Isaac. November 10, 2019

Sawan, Morgan. “Screenshot of Asking for Ride”, November 10, 2019

Sawan, Morgan. “Screenshot of post 1”, November 10, 2019

Sawan, Morgan. “Screenshot of post 2”, November 10, 2019

0 notes

Quote

Barista | Shutterstock

It’s time we stop considering these jobs as a backup and start providing dignity to all workers

I graduated from college in the spring of 2008. If you’ll recall, that fall wasn’t a great time to enter the job market, and the advice I got from anyone who had an opinion (which was everyone) was to “go wait tables.” It was a catchall phrase for the kind of work that was assumed to be available whenever the chips were down — the guidance given to every high schooler looking for extra money, every college grad who doesn’t have a job lined up, every aspiring actor in LA. And even at that time, when the unemployment rate was somewhere around 10 percent, it was available: I got a job as a hostess and server at a local restaurant, but I also had an offer from Starbucks, and an invitation to return to work at a bakery I’d worked at the previous summer.

Once again, we’re facing a recession, or, according to some experts, a full-on depression. Unemployment websites crashed as millions have applied for benefits in the past weeks, and food banks can’t keep up with demand — one-third of those going to them for food have never needed aid before. The coronavirus pandemic has revealed basically every fault line in our society, from the inadequacy of the social safety net to the incompetence of many of our leaders. And it is now revealing some long-held assumptions about work in the food-service industry. Being a server, a bartender, or a dishwasher, or doing other restaurant work, is often spoken of as a job that is always — and implicitly, only — viable when there are no other options. That if anyone had a real choice, they would choose something else. But because restaurants and bars aren’t hiring, food is no longer the fallback job. It never should have been thought of in that way in the first place.

The restaurant industry has long been the province of outcasts, but over the last two decades, owning a restaurant, becoming a celebrity(ish) chef, and, to a certain extent, being a fancy mixologist have come to be considered actual careers. These are the kinds of jobs that can land you a steady paycheck and the status of “small-business owner,” or even book deals and TV appearances. But when you’re not the owner or the creative force behind the food, food service — from hustling shifts as a server to manning the cash register at McDonald’s — is still generally talked about as a temporary detour, a place to lay low while you get your shit together. In pop culture, it’s an after-school job for teens, even though only about 30 percent of fast-food workers are teenagers. The mainstream image is still a job you leave, not one you keep.

“It’s an industry many fall back on time and time again,” writes Frances Bridges for Forbes. In 2011, Brokelyn told recent college grads that they likely “will consider waiting tables as a fallback to your day-job dreams,” the assumption being that everyone dreams of a day job. In 2016, Forbes called being a host or bartender one of the best jobs to have “while you are figuring out what to do with your life,” as it provides both a steady paycheck and, due to high turnover, restaurants and bars are “almost always hiring.” The assumption by economists and career experts was that no matter what, people need to eat, and they would want to eat out — so restaurant work would always be around.

Now, for the first time, it’s not. Nearly every state has issued orders for restaurants to close dine-in options or severely reduce capacity, forcing restaurants to lay off or furlough workers — or shutter entirely. About 10 million people filed for unemployment in the past few weeks, a number that’s expected to keep rising by the millions. And that number doesn’t account for gig-economy workers — like Instacart couriers or Uber Eats drivers — who, as contractors, wouldn’t qualify for UI. The food-service industry was hit particularly hard. According to the Department of Labor, restaurant and bar jobs accounted for 60 percent of the jobs lost in March. It’s clear that serving food and making drinks is not the revolving door it has been made out to be.

Jennifer Cathey, a former line cook at Glory World Gyro in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, says the restaurant has tried to stay open for takeout and delivery services, but there’s almost no business, and she was often “alone in a kitchen for hours at a time.” After a week, she volunteered to be laid off, as she lives with her mother and doesn’t need the money for rent. “If work was going to be so slow, it didn’t feel right to take any of the meager hours given to employees for any of my other coworkers,” she told Eater.

Cathey, who started working in her mother’s restaurant as a teenager, says she wanted to sacrifice her shifts for her coworkers because the food industry has always felt like home for her. “It is my favorite kind of work, I’ve loved all the places I’ve worked,” she says. Mostly it’s because she gets the immediate gratification of making something for someone else to consume and enjoy. But it’s also because, as a trans woman, the restaurant industry is a place she can rely on to be welcoming. “Especially living here in Alabama, all the people I’ve met through the restaurant and bar industries have been the most accepting of anyone,” she says. “I might not get anyone from my hometown to call me by my name, but the food-service community is tight-knit and open and welcome to all sorts of people... I have that fear that other industries wouldn’t be as welcoming.”

Unfortunately, it is also because food service has been a space for those who don’t fit into other parts of society that it has been considered a job for those who just need a job. Food service doesn’t require a college degree (or even a high school diploma), and it’s traditionally more welcoming to those with criminal backgrounds, to immigrants, to queer people, and to those with little other work experience. In Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain referred to line cooks as a “dysfunctional, mercenary lot” and “fringe dwellers.” Not the most generous reading, but one that speaks to the reality: that in most people’s opinion, any office job is preferable to a career in the restaurant industry.

Which is not to say it’s not worthy work. If this pandemic has proven anything, it’s how essential those working in the food industry are. Instead, these assumptions come from a cycle of low pay and bad benefits that devalue both the job itself and the people doing it. “It’s set up to be temporary,” says Lauren* (who asked to remain anonymous), who was recently laid off from her bartending job at Dock Street Brewery in Philadelphia. “There are minimal benefits, pay increases, or opportunities for moving up in a company. And then this happens, and it makes it even more apparent how the industry is set up to be temporary, even though the people working in it don’t see it that way.”

A “reasonable” person, says the strawman I’ve invented but also probably plenty of people you’ve actually met, wouldn’t choose to make a career out of a job that relies on tips, that doesn’t provide health insurance, and where one risks such injury. Thus, the people who choose this career must not be “reasonable,” and if that’s true, then why support such unreasonable people? And on and on.

If it were true that food service is only a paycheck for those who are waiting for their “real” career to appear, then presumably no one would care one way or another about the job itself. But multiple people I talked to spoke of the restaurant industry — waiting tables, working the line, making lattes — as their dream job. “I literally emailed Pizzana for two years until they gave me a shot,” says Will Weissman, who was recently laid off from the West Hollywood pizza restaurant. He loved the restaurant’s food from the first time he tasted it, and hoped when they opened a second location, they’d take a chance on him, even though he had no previous experience. “I had always been food obsessed. I know a lot about wine, I’m a good cook, and I just wanted to finally do something in the food industry.”

Samantha Ortiz, a chef at Kingsbridge Social Club in the Bronx, says she was instantly drawn to the hospitality industry when she started work as a barista. “I felt so fulfilled to be able to make something for someone, even if it was as simple as a latte,” she says. Now, her restaurant is closed and her unemployment will run out in 90 days, but she has no plans to switch industries. “I doubt that I would ever look for a job in a different field,” she says. “The kitchen is home.”

When my serving job ended (the restaurant shut down), I was slightly relieved. I was a terrible server, and I knew I had other options. But many of my coworkers expressed deeper laments. They liked the strong arms they got from carrying trays of food, and they enjoyed recommending a dish and hearing their customer loved it. They liked that each night was different and experimenting with making new drinks. Hearing from them, I understood that the restaurant’s closure was a loss.

It’s not quite true that there are no food-service jobs available right now. Instead of the serving jobs that college grads are urged to consider, there’s a new form of food work that’s thriving during this recession: the gig worker. Grocery stores and apps like Instacart are hiring deliverers and baggers by the thousands. It’s mostly temporary work, and puts workers at higher risk for contagion, but it’s there. In a vacuum, there’s a lot to love about a job as a gig-economy deliverer. Setting one’s own schedule, picking up shifts when it’s convenient, providing a necessary service to people who can’t travel or carry their own groceries — that’s a good job. What’s not good is the pay, the exploitation, the hundred ways these corporations leech off their workers and make it impossible to make a living wage. But that doesn’t have to be the case.

We as a society have set these jobs up to be temporary, so when someone wants to make their job permanent, we think it is a failure on their part, rather than a failure on ours. There is no such thing as a “bad” job, only bad conditions. Food-service work doesn’t have to be low paid. It doesn’t have to rely on tips, or come without health care or paid sick leave. In the face of the pandemic, we’re seeing how that is the case, as grocery stores and delivery services are pressured into providing better benefits and pay to these essential workers. But it’s time we stop considering these jobs, any jobs, as backup, and time to start providing dignity to all workers.

“It’s hard seeing people that I really care about, that I work with, be treated as disposable,” says Lauren. “I definitely go back and forth every day being like, ‘Is this even worth it, or am I just pouring all of my energy into continuing to be treated really poorly?’ I don’t know.”

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/34nd7lE

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/04/food-is-no-longer-your-fallback-job-it.html

0 notes