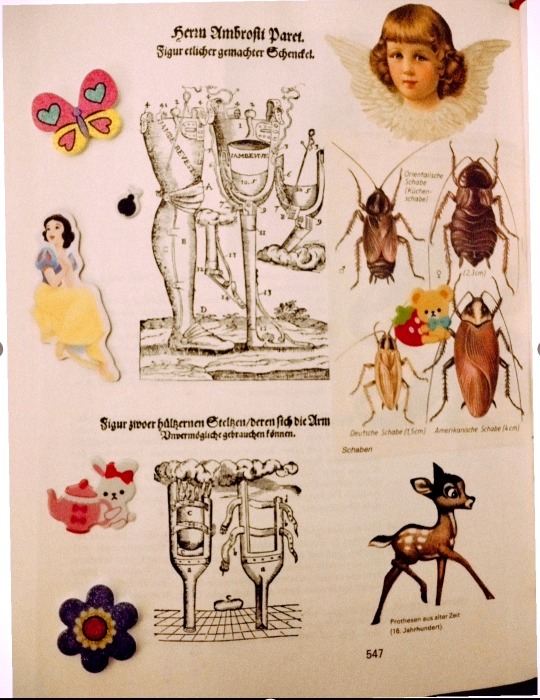

#historical prothesis

Text

#pages from my journal#my journal#personal#collage#angel#stickers#medical#historical prothesis#tw bugs#disney

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guides to the Eucharist in Medieval Egypt - A Review

In what might be the first work of its kind, Arsenius Mikhail’s Guides to the Eucharist in Medieval Egypt, being the first installment in Stephen J. Davis’ Christian Arabic Texts in Translation, presents us with translated excerpts from three different medieval Copto-Arabic commentaries on the Coptic liturgy. These texts are: 1) the 13th century priest Abu al-Barakat Ibn Kabar’s The Lamp of Darkness, 2) The Precious Jewel by Yuhanna Ibn Saba (a lesser known 13th century ecclesiastic), and 3) The Ritual Order, by 15th century Coptic Pope Gabriel V.

The book begins with a scholarly introduction, providing a brief biography as well as introducing the reader to the cultural and historical backdrop of each of the authors surveyed. We are told that the first author, Ibn Kabar, was a prominent government official under the Mamluk prince Baybars al-Dawadar prior to being forced out of his position by Sultan Al-Malik Al-Ashraf. He was eventually ordained priest of the hanging Church in old Cairo in 1300, passing away between 1323 and 1325. His magnum opus, The Lamp of Darkness, is a 24 chapter long treatise covering various topics from scripture, to canons, to dogmatics, to liturgics. The excerpts contained in this volume describe the Coptic liturgy of his day in meticulous detail, for the purpose of being used as an instruction manual for priests and deacons living in an age of great liturgical diversity (and perhaps even confusion) in the Egyptian Church.

The second author, Yuhanna Ibn Sabba, was a contemporary of Ibn Kabar and a lesser known ecclesiastical figure by comparison. He presents us with a more overtly doctrinal and theological work in his Precious Jewel. This is a vast work spanning over 100 chapters and a wide variety of topics both theological and liturgical. His writing betrays a knowledge of the works of pseudo-Dionysius and perhaps even Clement, Origen, and Cyril of Alexandria. Ibn Sabba remains an enigmatic figure in Copto-Arabic literature, little is known of his life or ecclesiastical career. That said, however, Mikhail remarks that his intricate knowledge of the rites and ritual of the medieval Egyptian Church indicates that he had direct access to the sanctuary. Throughout the treatise, he also displays an in-depth knowledge of the administrative affairs of the patriarchate, leading some to suspect he was the reigning Coptic Pope’s archdeacon. In many instances, Ibn Sabba offers descriptions of the liturgy that differ greatly from those provided by Ibn Kabar. This leads the author to believe that Ibn Sabba was accustomed to a liturgical rubric very different from the Cairo rite known to Ibn Kabar.

The third author, Pope Gabriel V, who sat on the patriarchal throne from 1409-1427, led an “unremarkable tenure,” according to the author. Formerly a tax collector, he took the name of Gabriel upon entering the monastery of St. Samuel of Qalamun during a turbulent time for Egypt’s Christians. The jizyah had been required of each individual Christian, rather than the entire community, relations with the Ethiopian Church had been strained, and the Venetian merchants stole the head of St. Mark. Despite these troubles, Pope Gabriel V took a keen interest in creating a single liturgical rubric to be used by the entire Egyptian Church, commissioning a delegation of learned priests, deacons, and other ritual specialists to canonize the standard rubric used by the Coptic Church to this day.

Mikhail is one of the few English-speaking scholars to specialize in the Coptic liturgy, earning his doctorate from the Faculty of Catholic Theology at the University of Vienna in 2017, specializing in liturgical studies and sacramental theology. He is known chiefly for his work The Presentation of the Lamb: The Prothesis and Preparatory Rites of the Coptic Liturgy, the first, and perhaps only, English language analysis of the Prothesis in the Coptic rite. The series editor, Stephen J. Davis, is a world renowned expert in Coptic and Middle Eastern Christianity, known for his contribution to such works as Disputation Over a Fragment of the Cross as well as AUC Press’ The Popes of Egypt series. Davis is also the author of the monumental work Coptic Christology in Practice, which might be one of the few scholarly works documenting the dispute between former Coptic Pope Shenouda III and Father Matthew the Poor written by a non-Copt.

There are two things that particularly stood out to me in the actual corpus of the translated works themselves: 1) Yuhanna Ibn Sabba’s interesting, if at times somewhat unconventional, theological claims. For instance, his claim that the water being mixed with wine during the liturgy is in commemoration of the Virgin Mary drinking water with wine during her pregnancy. Or in another section where he claims that God created man to replace the number of fallen angels who followed Lucifer in his rebellion. Perhaps even more interestingly, his assertion that the nine “holies” chanted in the Trisagion represent the nine angelic orders and that “the earthly Church resembles the heavenly Jerusalem,” with the priest as leader of the earthly ranks offering up the prayers of the people to the Trinity the same way the leader of each angelic rank offers prayers up to God on behalf of their fellow angels. As mentioned before, this indicates a knowledge of the pseudo-Dionysian corpus which I am surprised a medieval Copto-Arabic churchman would have had. 2) The authors’ collective willingness to co-opt traditional Islamic terminology to expound Christian doctrine. For instance, Ibn Sabba’s reference to prayer as a “proper duty and necessary obligation.” Or Pope Gabriel V’s claim that the New Testament, as a fuller and more complete revelation than the Old, contains in it “the injunctions and interdictions.”

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed the work and would highly recommend it to anyone interested in Christian Arabic literature, Coptic liturgy, or liturgical studies more generally. Mikhail’s translation is readily accessible to both technical and popular audiences. His introduction is packed with interesting and invaluable insights, and his meticulous research methods cover a lot of ground. The author went down into the weeds, using manuscripts from desert churches and monasteries, making note where different manuscripts varied throughout the translated texts and providing important justifications for certain translation choices. My only minor criticism of the book is that I wish the notes were a bit more comprehensive at certain times. I would have also loved for this work to include the original Arabic text alongside the English translation.

0 notes

Photo

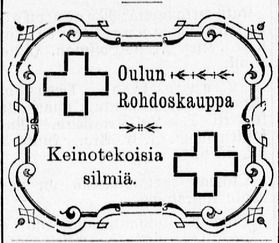

An adverticement from 1900 9th of January Kaleva magazine about arteficial eyes you can buy from pharmacy at Oulu city.

Kaleva started to appear in 1899 and is still going strong.

#oulu#eye#old newspapers#historical newspapers#prothesis#glass eye#pharmacy#old advertisement#1900's#vintage#old stuff#newspaper#history of healthcare#historia#suomen historia#history

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overanalysis Hours - You Can’t Go Home Again: How Oksana Uses Fire for Empowerment and Freedom

Why do we grieve?

We grieve for the familiarity of what we have lost, not for what we have never known.

This is especially true when it comes to mourning the loss of loved ones. How to “properly” grieve someone, and for how long, is a deeply personal matter. Some people find comfort in religion or ancient traditions; others throw themselves into work to keep a sense of forward momentum going; many people grieve by crying and outwardly displaying their painful grief (usually publically at funerals) whereas others withdraw and honour their private rituals.

Grief is one of the core themes that Season 3 intertwines along with family, fate, and independence. In S3E2, Carolyn has an interesting conversation with Kenny’s girlfriend:

This makes me wonder if Carolyn possibly feels embarrassed by her own grief, while also bearing the tremendous weight of it but not allowing herself to wail and shriek like her ancestors. Notably, Carolyn encourages Kenny’s girlfriend to not be embarrassed and to grieve openly.

Carolyn’s brief history lesson is significant because we see throughout this Season that Carolyn herself doesn’t grieve openly. Instead, she’s more closed off than ever, something that obviously bothers Geraldine. Their very opposite ways of grieving creates constant conflict at home.

Carolyn’s remark about the ancient Celts got me thinking about the different customs various cultures have to express grief and to honour their dead.

Like the ancient Celts, the ancient Greeks similarly expressed their grief openly during their funeral processions:

The Greeks believed that at the moment of death, the psyche, or spirit of the dead, left the body as a little breath or puff of wind. The deceased was then prepared for burial according to the time-honored rituals.

Relatives of the deceased, primarily women, conducted the elaborate burial rituals that were customarily of three parts: the prothesis (laying out of the body, the ekphora (funeral procession), and the interment of the body or cremated remains of the deceased.

Immortality lay in the continued remembrance of the dead by the living.

Furthermore, the ancient Greek funeral pyre was the alternative to a burial and a traditional grave:

So the procession moves through the still gloomy streets of the city-doubtless needing torch bearers as well as flute players-and out through some gate, until the line halts in an open field, or better, in a quiet and convenient garden.

Here the great funeral pyre of choice dry [wood], intermixed with aromatic cedar, has been heaped. The bier is laid thereon. There are no strictly religious ceremonies. The company stands in a respectful circle, while the nearest male kinsman tosses a pine link upon the oil-soaked wood.

A mighty blaze leaps up to heaven, sending its ruddy brightness against the sky now palely flushed with the bursting dawn. The flutists play in softer measures. As the fire rages a few of the relatives toss upon it pots of rare unguents; and while the flames die down, thrice the company shout their farewells, calling their departed friend by name.

So fierce is the flame it soon sinks into ashes. As soon as these are cool enough for safety (a process hastened by pouring on water or wine) the charred bones of the deceased are tenderly gathered up to be placed in a stately urn.

And in India, funeral pyres are a Hindu tradition:

Historically, Hindu cremations take place on the Ganges River in India. The family builds a pyre and places the body on the pyre. The karta will circle the body three times, walking counter-clockwise so that the body stays on his left, and sprinkling holy water on the pyre. Then the karta will set the pyre on fire and those gathered will stay until the body is entirely burned.

The symbolism of fire across time and place is often tied to passion, destruction, creation, rebirth, eternity, hope, and purification.

Fire certainly plays a crucial role in Oksana’s life. Before she became Villanelle, the little girl Oksana, abandoned by her mother in an orphanage, uses fire:

We’ve known since Season 1 that Oksana is an arsonist. And it’s clear that people have died from the fires she has caused. On the surface, Oksana does use fire for destructive purposes. In actuality, Oksana uses fire to empower and free herself.

Consider Tatiana’s statement that Oksana died in the fire, as the orphanage claimed. On a symbolic level, Oksana did die; a part of her child’s life was burned away along with the orphanage. And Oksana certainly did die when she decided to become Villanelle.

However, over time, Villanelle went from an empowering identity, a way for Oksana to free herself from her past, to being “an impossible standard” and “her own worst enemy” as Jodie Comer has revealed. So fire can also be self destructive to Oksana.

Keeping this in mind, we can think about the expression “you can’t go home again”. This refers to the fact that there comes a point in time when you can't truly go back to a place you once lived, because so much will have changed since you left that it is not the same place anymore.

By burning her family home down at the end of S3E5, Oksana ensures that she literally cannot go home again.

Neither can Bor’ka and Pyotor. It will take them years to realize this, but Oksana did them both a favour because she freed them. As much as she emancipated herself from her past through the act of burning the family home down, she propelled Bor’ka and Pyotor forward.

What Oksana did was a catalyst; if she hadn’t used fire, Pyotor would have probably rotted away in Grizmet for the rest of his life and Bor’ka would have continued to be abused by his shitty parents and Tatiana (and he would have missed Elton John’s farewell tour)

It is important to point out here that Oksana is once more an arsonist: destructive, empowering, and freeing. Her act of burning is an attempt to put her deeply painful past behind her, and it is in this way that Villanelle is forged in the flames as well.

The striking image of Oksana’s family home going up in flames also evokes the funeral processions of the ancients and their use of the funeral pyre. Oksana simultaneously murders her abusive mother (along with her other awful relatives) and performs a sort of funeral rite of her own. A cremation of her past, of who she could have been.

We watch the flames engulf Oksana’s family home, and we realize that this isn’t just an act of fury. It’s an act of mourning, too. This is Oksana expressing her grief, channeling it through Villanelle: the loss of the family she spent a few happy days reconnecting with-and also her way of grieving the happy childhood and loving family she has never known.

And then, like the Villanelle we know her as, Oksana goes forth into the night, wailing and shrieking, to become exactly who she was meant to be.

#Overanalysis Hours#Killing Eve#Season 3#Villanelle#Jodie Comer#Sandra Oh#Eve Polastri#Carolyn Martens#Fiona Shaw

86 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Global Cervical Disc Prothesis Market report provides information about the Global industry, including valuable facts and figures. This research study explores the Global Market in detail such as industry chain structures, raw material suppliers, with manufacturing The Cervical Disc Prothesis Sales market examines the primary segments of the scale of the market. This intelligent study provides historical data from 2015 alongside a forecast from 2020 to 2028.

0 notes

Text

INMOOV|ROBOT LOVE - digging deeper

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, French sculptor and designer Gael Langevin started his project called ‘InMoove’. It started as a hand prothesis and, over time, developed into a human-size 3D-printed robot that is able to talk, see, move and hold onto something. It is now even possible to build your own version of this robot, since there is an open access to all information. The network shares the knowledge and innovation about the robot and its technology. Langevin believes that a huge benefit of this project being open-source is that it is enabled to have a wide reach and thereby goes through a larger development.

In 2015, a photographer Yethy proposed to do a photo session in Gael’s workshop with whatever moods and feelings the author of the artwork had. The photograph they made is the piece I want to apply digging deeper to and express my feelings towards it.

Unfortunately, I can't post the photograph because of Tumblr restrictions, however, it can be found here : http://inmoov.fr/gallery-v2/ (robot holding a baby)

What I find particularly appealing about this artwork is the contrast and the controversial meaning behind it. Baby skin in the photograph looks very soft, warm and sensitive, while robot ‘skin’ looks rather cold and harsh. Moreover, baby is sitting in a very natural way comparing to the robot, whose moves look dramatically artificial and have absolutely nothing to do with love and happiness that comes from a real person holding a baby. Also, the high contrast dissimulates the face of the baby, just like InMoov seem to come out from the darkness. Robot is not even looking at the baby, its face looks emotionless, and the baby himself/herself is turned away from robots’s face.

All these aspects that I have noticed might be pointing out the down-side of technological revolution. I strongly believe that soul and emotions are the things that separate us, human beings from animals, plants and machines. However, as can be seen through this artwork, there is no way robots can replace humans in these manifestations of humanity, because they are lacking the most important ingredients that I have aforementioned.

Even though the robot holding a baby might have been an attempt to convince that the future of technological revolution is alright and we can absolutely trust robots (since babies are really fragile and the one who’s holding it must be extremely trustful), I wouldn't agree with such statement. This photograph is giving me scary thoughts about our future: are humans going to be replaced with robots? Are robots going to raise children? If this robot is holding a baby, might he/she be baby’s parent? If yes, how does it feel like to be in a relationship with a machine? I do hope that we will never know.

Even though this piece gives me goosebumps, I find it very meaningful and successful, since it has literally brought my ideas about the frightening future to life and gave me some thoughts about the power of lighting, arrangement and photography itself. I feel that a strong quote added to this photograph would make the message even stronger, although, making a poster out of this work rather than a photograph.

3:1 KEY THEMES OF THE ARTWORK

Robot

Technology

Photography

Contrast

Relationship

3:2 WORD ASSOCIATION

Robot: artificial, emotionless, soulless, artificial intelligence, individuality, uniqueness, character, habits, attitude, person, human being, humanity, humanism.

Technology: progress, future, computer, robotic, mechanism, remote-controlled, programmed.

Photography: art, white balance, ISO, arrangement, lighting, background, model, message, hidden message, meaning.

Contrast: black and white, comparison, difference.

Relationship: love, trust, human, real, natural, fake, artificial, unreal, sci-fi, future, disaster, apocalypse.

3:3 RELATED ARTICLES:

‘Hi, Robot’ by Frieze

An article focusing on the second-wave effects of the ‘digital revolution’, or the capacities for automation, AI, and robotics to fundamentally shift the ways we work, speak, relate, love, criminalize and, yes, perhaps obliterate one another. It insists on asking yourself: so will the robots kill us all or will we do it ourselves? In an age of automation and robotics, how will we relate to one another? Do we need a new code of ethics? It also includes a review of the exhibition ‘Hello, Robot”, focused on ‘design’ as an interface between human and the machine. There is a small extract from the article that summaries my thoughts and gives a hope for a better future: ‘If our robots have developed, then our feelings for and against them largely haven’t: they still serve as playthings for us humans to live out our dreams, hatred and perhaps love.’

‘Artificial Amsterdam: The City As An Artwork’ by e-flux

An article about the exhibition, that depicts how the dynamic of cities is causing dramatic changes in society and culture worldwide. Cities are experiencing vast damage, economic, social and cultural shocks that they are not prepared to assume. Amsterdam is the opposite example of a city from disappearing into the waters. The term ‘artificial’ pops frequently when referring to Amsterdam. It does not only allude to the physical character of a city ‘stolen’ to the sea, but to a general feeling about the city’s life, culture, its submission to tourism, its paradoxical ruled liberality… a place where everything is under control, impost card city.

‘All Too Human Dinner” by TATE

This article does not aim to review any artworks, it is rather an announcement, informing that visitors go the ‘All Too Human’ exhibition will be able to have a dinner provided by Tate Britain afterwards. The relationship between the name of the exhibition and picture of food made me think of humanity and our natural habits regarding consuming food, which has become a ritual, even a cult nowadays. Is this food religion going to disappear along with the digital revolution?

3:4 WHAT I THINK ARTIST HAS RESEARCHED WHILE MAKING THIS WORK

Ironically, human body and its functions, in order to build a proper, human-looking robot. As for the photograph, I think he must have researched old renaissance paintings illustrating bright emotions and feelings, human relationship, in order to compare it to relationship between human and a machine. I feel that the famous icon of Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus was taken as an example for the arrangement and composition of the photograph. Comparing Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ to a robot holding a baby is extremely brave and provoking; a throwback to history of humanity and sneak-peak to the future where it might disappear. Obviously, an important aspect of the research must have been human feelings from the psychological point of view; how people are going to view the artwork and what kid of feelings towards it are going to appear, what this piece reminds of and how it can provoke the debate insight viewers’ mind.

HOW THE ARTWORK RELATES TO CURRENT NEWS

One of the most considerable and questionable inventions of our century is, undoubtedly, crypto currency, which arises questions similar to those that appear while thinking of digital revolution and robots: why was it created? How is it going to change our lives? Is it going to replace or destroy the existing system? Cryptocurrency, although being decentralised, is not gaining trust from the major percentage of population, just like artificial intelligence and robots. Nobody knows the true aim of making those aforementioned and how cryptocurrency and robots are going to change our lives. Even though crypto currency, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, is made for human-use, it seems like someone is giving us a hint that soon we will only have digital currency for digital beings.

Since technological revolution is taking our world by storm, this artwork can relate to many current events in this field: the strikingly expressive android child’s face, developed on November 15, 2018 in Osaka University, flexible electronic skin for human-machine interactions, presented on November 28, 2018 by American Chemical society and many more. All these inventions are super promising and high-brow, yet so frightening and warning.

HOW THE ARTWORK RELATES TO HISTORY

The first historical event that pops in my head while looking at this artwork is the invention of the first computer. The first mechanical computer, created by Charles Babbage in 1822, doesn't really resemble what most would consider a computer today. Therefore, this document has been created with a listing of each of the computer firsts, starting with the Difference Engine and leading up to the computers we use today. The word "computer" was first recorded as being used in 1613 and originally was used to describe a human who performed calculations or computations. The definition of a computer remained the same until the end of the 19th century, when the industrial revolution gave rise to machines whose primary purpose was calculating.

I feel that this life-changing invention has started the thing we now call ‘digital revolution' in its worst sense, exposing peoples’ personal space into social media and replacing spiritual values with those non-existing digital ones.

RELATED ARTICLES

‘Hi, Robot’ by Frieze

An article focusing on the second-wave effects of the ‘digital revolution’, or the capacities for automation, AI, and robotics to fundamentally shift the ways we work, speak, relate, love, criminalize and, yes, perhaps obliterate one another. It insists on asking yourself: so will the robots kill us all or will we do it ourselves? In an age of automation and robotics, how will we relate to one another? Do we need a new code of ethics? It also includes a review of the exhibition ‘Hello, Robot”, focused on ‘design’ as an interface between human and the machine. There is a small extract from the article that summaries my thoughts and gives a hope for a better future: ‘If our robots have developed, then our feelings for and against them largely haven’t: they still serve as playthings for us humans to live out our dreams, hatred and perhaps love.’

‘Artificial Amsterdam: The City As An Artwork’ by e-flux

An article about the exhibition, that depicts how the dynamic of cities is causing dramatic changes in society and culture worldwide. Cities are experiencing vast damage, economic, social and cultural shocks that they are not prepared to assume. Amsterdam is the opposite example of a city from disappearing into the waters. The term ‘artificial’ pops frequently when referring to Amsterdam. It does not only allude to the physical character of a city ‘stolen’ to the sea, but to a general feeling about the city’s life, culture, its submission to tourism, its paradoxical ruled liberality… a place where everything is under control, impost card city.

‘All Too Human Dinner” by TATE

This article does not aim to review any artworks, it is rather an announcement, informing that visitors go the ‘All Too Human’ exhibition will be able to have a dinner provided by Tate Britain afterwards. The relationship between the name of the exhibition and picture of food made me think of humanity and our natural habits regarding consuming food, which has become a ritual, even a cult nowadays. Is this food religion going to disappear along with the digital revolution?

BOOKS IN THE LIBRARY

‘Is man a robot?’ by G.L.Simons, 1939

‘Becoming a robot’ by Narn June Paik, 2014

‘A guide to digital revolution’ by PACS, 2006

‘How machines think: a general introduction to artificial intelligence’ by Nigel Ford, 1987

‘Artificial Intelligence’ by Patrick Henry Winston, 1992

3:5 SUMMARY

In conclusion, referring to the expanded research and applying it to the original artwork, it becomes obvious that digital revolution is both a great invention and a huge issue of our age. As anything else, it has both benefits and drawbacks, however, looking back at the original artwork, it seems that those down-sides outweigh the pluses of robots and digitalising process. The more digital creations are being developed, the more humanity is dying. InMoove is a very successful piece that illustrates frustrating and frightening future, a future without kindness, love, individuality and, unfortunately, humanity.

This expanded research gave me an astonishing abundance of thoughts regarding digital revolution and my own artworks. I might relate my art to my apocalyptic view of the future, expanded and developed by this research.

I would like end by summarising the moral of this research through Erich Fromm’s quote: ‘he danger of the past was that men became slaves. The danger of the future is that men may become robots.’

0 notes