#historian: egon caesar conte corti

Text

“Did you bring the Heine souvenirs with you?”: Rudolf’s last Christmas present for his mother

As Christmas approached, I started to search for Habsburg stories related to this holiday to share with you, and almost inevitably I once again looked into Crown Prince Rudolf’s last Christmas. The Christmas Eve of 1888 is known mostly for having been full of ominous signs of Rudolf’s deteriorating mental health that his family either was unable to notice or simply chose to ignore. I have a second post coming up related to that, but in this post I’m covering a different topic: the last present Rudolf gave to his mother, Empress Elisabeth.

December 24 was a special day for the Imperial family not only because it was Christmas Eve, but also because it was Elisabeth’s birthday. It was, then, a double celebration for the family. And on the 24th of December of 1888 the Crown Prince surprised his mother with a very special gift: a bundle of letters written by her favorite author, the poet Heinrich Heine.

Elisabeth’s deep admiration for Heine was well known: months earlier she had publicly supported and financially collaborated in the creation of a monument in honor of Heine in Düsseldorf, the poet’s hometown. The project, however, had a huge backlash by the anti-semites and German nationalists (Heine was Jewish), and soon Elisabeth was attacked by them. The campaign against Heine’s devotees in the press was so strong that eventually Elisabeth was forced to withdraw her support; the monument, rejected from city to city in Germany, finally was placed in New York, where it still stands (Hamann, 1978, 1986).

Rudolf, who had long been a supporter of Jewish rights, was probably happy to find that his mother shared his sentiments regarding the growing anti-semitism of the late 19th century. It was likely the fiasco of the monument that prompted Rudolf to get the Empress a Heine-related birthday and Christmas gift. For this task he asked his friend, journalist Moritz Szeps, to travel to Paris and acquire for him a bundle of letters that Heine wrote to his friend Alexander Weill. We can find a mention of it in this undated letter Rudolf wrote to Szeps, likely from the first days of December (translation by DeepL, nuances may be lost):

Dear Szeps!

I am glad to know you are here; I would like to thank Frischauer [another journalist friend of Rudolf and Szeps] very much for his letter yesterday and its enclosures. Did you bring the Heine souvenirs with you? I hope to see you in the next few days. With best regards

Your Rudolf (Szeps, 1922, p. 168)

And again, on December 11:

Dear Szeps!

Thank you very much for your letter. Please have Heine’s letters photographed and only then send them to me.

I hope to be able to see you the day after tomorrow.

With warmest regards

Your Rudolf (ibid)

In 1908, writing in the December 25 edition of the Neue Freie Press, Hugo Wittmann claimed that Weill, instead of money, had demanded “nothing more for his treasure than that the Crown Prince asked him for it in writing and send him a photographic copy of the papers upon receipt” (DeepL translation) which would explain why Rudolf asked Moritz to first photograph the letters before sending them to him. Historian Brigitte Hamann, however, claims differently: according to her the Crown Prince in fact paid an exorbitant amount of money for the letters. Whatever the case, when the Imperial family opened their presents at 4 o’clock in the afternoon of Christmas Eve, Elisabeth found a packet full of letters of her favorite poet.

This was, no doubt, a touching personal present that shows how much Rudolf cared for his mother. But what did Elisabeth think of this gift? As always, Hamann’s The Reluctant Empress is very straightforward:

In order to prove that he revered his mother, Rudolf paid an outrageous price in Paris for eleven Heine autographs and placed them under the Christmas tree for the Empress. Elisabeth, however, was so preoccupied with her daughter's engagement that she did not pay Rudolf’s gift the attention he had expected. (1986, p. 339)

Reading this, I’ve always felt sorry for Rudolf: he clearly put a lot of thought into finding the perfect present for his mother, only for it to go unnoticed. At least, that’s what I believed until I read Hamann’s previous work, her biography of the Crown Prince published first in 1978:

Whether the Empress appreciated the shy homage of her son, whether she felt how much he practically vied for her understanding, since both of them were attacked by the same people, is highly unlikely. According to all sources, Elisabeth at this time was totally occupied with Valerie, her “only one,” with her engagement and the impending pain of parting with her favorite child. (2017)

“Highly unlikely”. No source backing this up. It was then when I realized that Elisabeth disregarding her son’s present was pure speculation on Hamann’s part. Between her biography of Rudolf and her biography of Elisabeth she seems to have convinced herself that the empress didn’t care for the letters at all, and “unlikely” became just “she did not pay attention”.

I won’t be too harsh on Hamann: I also think Elisabeth’s main concern that Christmas was Valerie’s engagement. According to Valerie’s diary, both her parents were very moved that day because she was going to get engaged in the evening. But that doesn’t have to mean that Elisabeth didn’t care for Heine’s letters. We just don’t know what Elisabeth thought of the gift, since (as far as I could find) none of the people that were present during the unwrapping of the gifts wrote down her reaction. Valerie only wrote in her diary that “Little Elisabeth [Rudolf’s daughter] was very happy about the presents and played with her things while we dined in the Alexandrian room on the left” (1998, p. 164). And the next time Rudolf wrote to Szeps, on December 27, the only allusion to the past Christmas Eve he made was thanking him for his “congratulations on the happy family event” (1922, p. 168) i.e. the engagement of his sister. No mention of Heine by anyone, anywhere.

We do also have, however, an interesting account of the opening of the presents in Egon Corti’s 1934 biography of Empress Elisabeth:

And so Christmas Eve, 1888, came round, and with it Elizabeth’s birthday. Rudolf and his wife were among the guests, and the Crown Prince presented his mother with Hugo Wittmann’s edition of Heine’s letters, at which Francis Joseph cast an ironical glance but made no comment. (p. 386)

No mention of Elisabeth’s reaction to the letters, but he does give us Franz Josef’s. Sadly Corti does not give a source for this account, which opens a new mystery: from where did he learn this? There is a mistake in the quoted fragment: the letters Rudolf acquired were original, written by Heine himself; Hugo Wittmann only published them in the aforementioned Neue Freie Press edition of 1908. But I wouldn’t straight up disregard this account either: not only Corti had access to now lost primary sources, he also worked closely with Valerie’s children. Who knows, maybe this was a family anecdote he learned from them.

So, did Elisabeth ignore her son’s thoughtful gift because all she cared about was Valerie’s engagement? We can’t know for certain. I think it is safe to assume Valerie was her main priority that day, but unless a primary source that explicitly states that she did not care for the letters appears, I don’t think it’s right (nor fair) to claim that she was indifferent to Rudolf’s present.

Sources:

Corti, Egon Caesar Conte (1936). Elizabeth, empress of Austria (translation by Catherine Alison Phillips)

Hamann, Brigitte (2017). Rudolf. Crown Prince and Rebel (translation by Edith Borchardt)

Hamann, Brigitte (1986). The Reluctant Empress: A Biography of Empress Elisabeth of Austria (translation by Ruth Hein)

Schad, Martha and Schad, Horst [ed.] (1998). Das Tagebuch der Lieblings Tochter von Kaiserin Elisabeth. 1878-1899

Szeps, Julius [ed.] (1922). Kronprinz Rudolf. Politische Briefe an einen Freund. 1882-1889

Wittmann, Hugo (1908, December 25). Ein Geschenk des Kronprinzen Rudolf an seine Mutter, Neue Freie Press

#tl;dr: hamann's bias strikes again#crown prince rudolf of austria#empress elisabeth of austria#heinrich heine#historian: brigitte hamman#historian: egon caesar conte corti

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have anymore info on Elisabeth's hofdame Helene of Thurn and Taxis? If I google her, I only get Helene in Bavaria, Sisi's sister, but she married into the Thurn and Taxis family in 1858 when the other Helene supposedly began to serve (*cough* what a conincidence). But I also can't find that Helene among the sisters-in-law, so I am curious who she is.

Very little, but yes. The problem with this lady, as you noticed, is that she often gets mixed up with Elisabeth's sister, but they were two completely different people (even the Austrian National Library has a picture of this Princess Helene identified as Helene in Bavaria).

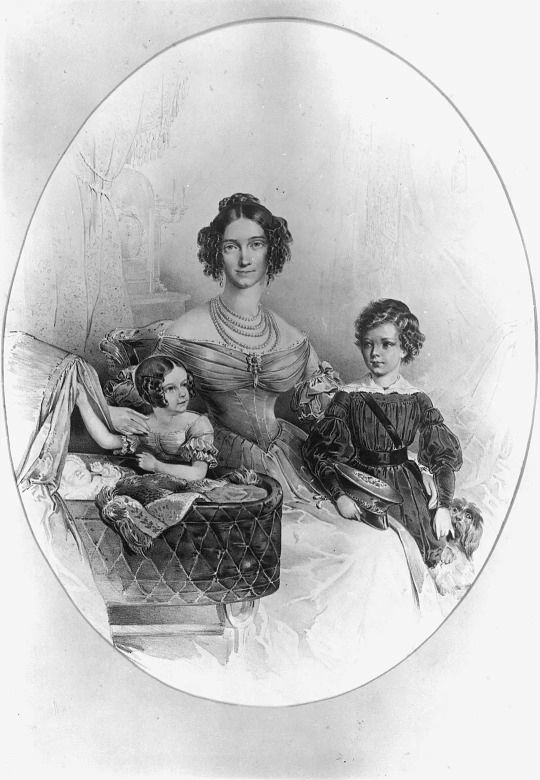

Princess Helene of Thurn und Taxis, by Ludwig Angerer, circa 1865 (Wien Museum).

Marie Helene Sophie was born in 1836 as the third child and second daughter of Prince Friedrich Hannibal of Thurn und Taxis and his wife Countess Maria Antonia Aurora Batthyány. The Thurn und Taxis family was huge, Helene belonged to the Bohemian branch funded in the late 18th century, so she was only distantly related to Nené's husband (they were like third cousins). We know little to nothing about her life, only that she served Elisabeth as a hofdame since 1858 until her marriage to Count Wolgang Kinsky in 1871. She probably got her position because her father, who died in 1857, had been the empress' Oberhofmeister (nepo baby). She was part of the retinue that accompanied the Empress to Madeira and Corfu in 1860-1861, and was one of the ladies in this "scandalous" photo taken in Madeira:

Helene is the lady sitting in the left corner, standing behind her is Lily Hunyady, sitting next is Elisabeth, and besides her is Mathilde Windisch-Graetz (via ÖNB).

Now you may be wondering, what's so scandalous about this picture? Well, that people at this time thought that Elisabeth was literally dying. When she left Vienna her illness was considered so grave that it was believed she wouldn't survive. And then this photo pops out: the dying empress happily playing an ukelele, enjoying the fresh air with her ladies. Wasn't she sick? Why does she look like she's just having some nice vacations? Suddenly the trip to Madeira looked less like a journey for health issues and more like a flight from Vienna.

Historian Egon Corti quoted in his biography of the empress some of the letters Helene wrote when they finally returned to Vienna, and they paint an interesting portrait of the state of the imperial couple when they reunited (Corti doesn't date this letter):

Now we have her back in this country, just as we had two years ago; yet how many things lie between — Madeira, Corfu, and a world of troubles. . . . She [Empress Elisabeth] was received with an enthusiasm such as I had never heard before in Vienna. On Sunday there is to be a choir festival [Liedertafel] and a torchlight procession at which fourteen thousand people have expressed their intention of being present. His [Emperor Franz Josef] expression as he helped her out of the carriage I shall never forget. I find her looking blooming, but her expression is not natural, it is as forced and nervous as it can be, her color so high that she looks overheated, and though her face is no longer swollen, it is much thickened and changed. The fact that Prince Karl Theodor [Elisabeth's brother] accompanied her proves how much she dreads being alone with him and all of us...

Another letter Helene wrote from the Schönbrunn on September 15, 1862:

She does not seem at all anxious to let us attend her now (...) She walks and drives out a great deal with His Majesty, but when he is not here she stays alone here in the part of the garden at Reichenau which is closed to the public. However, God be praised, she is at any rate at home, and inclined to remain here ; that is the main thing. She is very nice to him — before us, at least — talkative and natural, though alla camera there may be many differences of opinion — that is often plainly to be seen. She looks splendidly, quite a different woman, with a good color, strong and brown; she eats properly, sleeps well, does not tight-lace any more, and can walk for hours, but when she stands there is a vein in her left foot which throbs. The Queen of Naples [Elisabeth's sister] does not look well — that household seems to be going badly.

A bit of a side note, but allegedly Queen Marie of Naples was pregnant with an illegitimate child at this time, and gave birth only a month later. Now I wonder, wouldn't they have noticed if she was eight months pregnant? Like is it even physically possible to cover up that with a corset?

Continuing with her letters, the last one Corti quotes is this one she wrote to Countess Caroline Wimpffen, née Countess Lamberg, who married in 1860 and therefore left service before the trip to Madeira:

I can only congratulate you upon not having had to go through these two years of martyrdom with us. Now we are settled in Schönbrunn, and the thought that we are ‘settled for good somewhere’ [in English in the original] seems quite strange. It was hard for her to give up her recent traveling about, and I quite understand this. When one has no inward peace, one imagines that it makes life easier to move about, and she has now grown too much accustomed to this. For the rest, Helene [Elisabeth’s sister] is coming here for a fortnight while the Emperor is away hunting, for he will not give that up... She still exerts a calming influence, for she is so sensible and orderly herself and tells her the truth. She [Elisabeth] went out riding at Reichenau, and has done so here once at seven in the morning, alone with Holmes. The walk has naturally become a gallop, but she does not want to trot yet. She simply refuses to let herself be accompanied by Grünne [former First General Adjuntant, now Master of the Horses] and Königsegg [Elisabeth's Oberhofmeister]. The former has been entirely ignored and avoided so far. Otherwise, thank God, things are going on well... I believe, indeed, that she has moments of despair, but nobody can laugh like her, or has such childlike whims. She says herself that it is not unpleasant to her to see us occasionally, but it is odious to her to have us in waiting...

We have, however, one last letter, this one quoted by author Joan Haslip in her biography The Lonely Empress. Helene wrote it to archduchess Valerie's former British governess Mary Throckmorton, whom she had befriended during her time at the Viennese court:

This year brings good news. Our beloved Empress has graciously condescended to appear once more at a great rout at the Burg. Although in deep mourning, everybody tells me that she looked as grand and gracious as ever, and had a kind word for everyone of the numerous people who were presented to her. Her face, though still handsome, tells of the pain and sorrow she has gone through, and the sadness in her eyes brought tears into those of all who were present. One is so thankful for the great effort she imposed on herself.

As always Haslip doesn't cite her source however in the foreword she thanks Sir Robert Throckmorton for giving her access to Mary's unpublished letters and journals, so I assume that is where she got this letter from. She doesn't date it but it's from the 1890s.

Helene died in 1901, aged 65-years-old, of what I couldn't find. She had outlived her husband by almost sixteen years.

Sources:

Corti, Egon Conte (1936). Elizabeth, empress of Austria

Haslip, Joan (1965). The Lonely Empress: a biography of Elizabeth of Austria

Helene Prinzessin von Thurn und Taxis, on Geni

#helene of thurn und taxis countess kinsky#empress elisabeth of austria#historian: egon caesar conte corti#historian: joan haslip#asks

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

By the beginning of 1860 the young Empress was living in a state of incessant agitation. Three confinements in the space of four years, the vicissitudes of the war, and her constant feud with the Archduchess [Sophie] and her clique had undermined her health. And now another thing happened which she felt most acutely, for she had a very strong family feeling. The idea of a united Italy had taken great strides since the campaign of 1859, and her brother-in-law’s position suffered in proportion. The King and Queen of Naples knew not a moment’s peace. Sporadic risings broke out, and in May Garibaldi started out on his famous expedition of the Thousand, which at a single blow severed Sicily from the Kingdom of Naples, and, when Palermo fell on June 6, 1860, showed the whole world that the Bourbon regime had feet of clay. Appeal after appeal for help went forth from Naples to the courts of Europe, and naturally to Vienna among them. Elizabeth implored her husband to intervene, but since his unsuccessful campaign the situation was such that no assistance could possibly be given. On June 13 Dukes Ludwig and Karl in Bayern arrived secretly at Laxenburg on a visit to the Empress, and discussed every possible and impossible plan for helping their sister, but all in vain. The Dukes were able to observe the state of Elizabeth’s nerves and general health, and to see what a pitch the antipathy between her and her mother-in-law had reached.

It was a long time since she had spent much time with her dear ones in Bavaria, and she now promised to pay them a visit in July. At Possenhofen, too, everybody was very much upset about the fate of the Queen of Naples. They heard that the King reigned but did not govern and was quite unfit to cope with the emergency. Garibaldi was already thinking of crossing over to the mainland from Sicily. The Austrian minister reported that the King of Naples had hardly anybody left upon whom he could really depend. Yet the Queen was in favor of his defending his crown by arms at all costs. Then, on August 21, Garibaldi landed in the south of the peninsula, and everywhere both army and people went over to him. King Francis looked on apathetically, but his twenty- year-old queen [sic Queen Marie was actually only 18-years-old] was admirable in her energy and courage. She was said to have told her husband that if he did not place himself at the head of the troops which still remained loyal, she would do so herself.

Meanwhile the magic name of Garibaldi was doing its work, and all that remained to the King was to retire into the fortress of Gaeta. For his own part, he would have preferred to throw up the whole thing. He only put up a defense in order to secure a successful retreat, and because he was shamed by the demeanor of his wife, whose courage rose as the danger increased, a characteristic in which she resembled her sister the Empress. Elizabeth felt the deepest sympathy with her sister’s fate, and the consciousness that she herself had to sit by with hands folded increased her nervous irritability.

Corti, Egon Caesar Conte (1936). Elizabeth, Empress of Austria (translation by Catherine Alison Phillips)

#empress elisabeth of austria#queen marie sophie of the two sicilies#francesco ii of the two sicilies#duke ludwig wilhelm in bavaria#karl theodor duke in bavaria#historian: egon caesar conte corti#historicwomendaily

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last Queen of Naples and the last Empress of Mexico

Some weeks ago I finished Joan Haslip's biography on Maximilian and Charlotte, and one little tidbit that I found really interesting is that during her stay at Rome, when Charlotte had her mental breakdown, she was visited by the deposed Queen and King of the Two Sicilies, Marie and Francesco. I looked it up but I couldn't find much more, so here is a compilation of all the quotes I found about it, from the oldest to the most recent:

A MELANCHOLY INCIDENT is related of the Empress of Mexico. Some little time ago, while still labouring under the delusion that she was being poisoned, she was visited by the Queen of Naples, and looking steadily at her, said, "Ah! how you are changed! I see they are also slowly poisoning you. What a change! What a change!" "Could anything," adds the Contemporary Review, "be more sad than such a meeting of the two unfortunate Queens?"

Dorset County Express and Agricultural Gazette, 11 December 1866

October 8, at noon, the Empress received the visit of the once King and Queen of Naples, who were at that time in Rome. They advised her to be calm and to eat and drink without fear. "Be careful not to let them poison you too", was the answer of the Empress.

Corti, Egon Caesar (1944). La tragedia de Maximiliano y Carlota

The King and Queen of Naples, who were living in exile in the Farnese Palace, were among the Empress’s first visitors, and Maria Sofia wrote to her sister Elisabeth in Vienna that they found Charlotte ‘in a state of nervous agitation, talking incessantly of poison’.

(...)

The following day, brother and sister were seen arm in arm touring the sights of Rome and Philippe was amazed at Charlotte’s knowledge of the churches. But the effort was too much for her tired brain, and after her farewell visit to the King and Queen of Naples, the Queen noted, ‘Poor Charlotte’s condition has sadly deteriorated.’

Haslip, Joan (1971). The Crown of Mexico: Maximilian and his Empress Carlota

On October 9 the Empress and the Count of Flanders left the hotel arm in arm for the railroad station. The King and Queen of Naples came to see them off and tried to calm her, saying she should not be afraid to eat or drink. She replied that they should be careful; the poisoners were everywhere; they had poisoned her mother and father, Albert Prince Consort, Lord Palmerston, many others.

Smith, Gene (1974). Maximilian and Carlota: the Habsburg tragedy in Mexico

As you can see, they are all kinda similar. I couldn't find more info about what kind of relationship Marie and Charlotte (and Francesco too, let's not forget about him) had before this, but I assume they weren't close at all, given that this seems to be their only recorded interaction. In any case, I agree with the first quote: this was a sad meeting.

#empress carlota of mexico#queen marie sophie of the two sicilies#francesco ii of the two sicilies#historian: egon caesar conte corti#historian: joan haslip#historian: gene smith#Dorset County Express and Agricultural Gazette#journal article#historicwomendaily

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

(...) The court protocol was solemnly fullfilled. The new little princess came to the world at forty-three minutes past ten at Christmas Eve. And as soon as such a happy event had taken place, the ministers that had to attest to the birth were led to the Duchess [Ludovika]'s boudoir. The midwife presented to them the newborn. Numerous court gentlemen and ladies were reunited in the chamber. The girl is examined and admired accordingly. Everyone comment the singular circunstance that, just like in Napoleon's case, the newborn already shows a little teeth. It is the general opinion of the courtiers that this singularity can be interpreted as a happy omen, to which they add the fact that she was born on Christmas Eve. A present from God on Christmas, and on a Sunday!

The Queen Elisabeth of Prussia was her godmother, and placed her name on the newborn, although that Christmas angel will always be familiarly called Sisi.

Corti, Egon Caesar Conte (1945). Elisabeth, la emperatriz enigmática (translation to Spanish by Jaime Bofill y Ferro, from Spanish to English by me)

ON THIS DAY, IN 1837, DUCHESS ELISABETH AMALIE EUGENIE IN BAVARIA, LATER EMPRESS OF AUSTRIA AND QUEEN OF HUNGARY, WAS BORN. She was the fourth child and second daughter of Duke Maximilian in Bavaria and his wife, Princess Ludovika of Bavaria. At 16 years-old she married her cousin Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria and became the second to last Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary.

#happy bday girl! it's been 184 years and we cannot shut up about you<3#empress elisabeth of austria#ludovika of bavaria duchess in bavaria#duke ludwig wilhelm in bavaria#helene in bavaria hereditary princess of thurn und taxis#house of wittelsbach#historian: egon caesar conte corti#elisabeth la emperatriz enigmática (1945)#on this day in history#historicwomendaily

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know if the letters from Ludwika and his family are available? Thank you.

Hello! As far as I am aware, Ludovika's letters aren't available in a compiled volume - as, say, Queen Victoria's letters are. Her letters are scattered across different archives in Germany. Two historians that had access to them and used them in their biographies on Empress Elisabeth are Egon Caesar Conte Corti and Brigitte Hamann; in their works Ludovika's letters are quoted many times (both of these have been translated to English as well as many other languages). I haven't read it yet but I'm sure that Christian Sepp's biography on Ludovika must have some of her letters, since I read he used mostly primary sources for his work.

The closest we have to Ludovika's words being compiled and published it's Erinnerungen an Großmama (Memories of Grandma), a manuscrit of 160 pages written by Duchess Amelie of Urach, Ludovika's granddaughter, and it's basically a compilation of family stories that her grandmother told her. Christian Sepp published them last year (let's all manifest that the new wave of Sisi shows and movies will give us a translation of this).

About other family members, there's Unsere liebe Sisi, a book in which Gabriele Praschl-Bichler argues against the common idea that Sophie hated Elisabeth and was set in making her life imposible, using letters from Sophie and other family members; it's only in German though. Another sister of Ludovika whos letters are available is Princess Auguste, Duchess of Leuchtenberg, but you'll have to dig in a bunch of Napoleonic books to find them. Elisabeth's letters to her lady-in-waiting and friend Ida Ferenczy have also been published (Kaiserin Elisabeth ganz privat - as you can guess by the title, it's only in German). Not letters but in the primary sources territory we also have the diary of Archduchess Marie Valerie that was published some years ago and has been translated to Italian, Hungarian and Czech. There must be more, but that's all I can think off the top of my head. I'll try to look out for more and see if there's something available online.

Hope I could help you!

#ludovika of bavaria duchess in bavaria#since like 80% of Ludovika's sisters were queens there letters must have been used in more historian's works but I don't know of any other#asks

4 notes

·

View notes