#herstorical black women

Text

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797 - November 26, 1883)

Born Isabella Baumfree, Sojourner Truth was a slave in Ulster County, New York. Enslaved by Dutch sellers, Dutch was her first language. She was sold many times until 1826 when she escaped slavery (Truth ran away with her infant Sophia to a nearby abolitionist family, the Van Wageners, who bought her and freed her).

In 1829 she moved to New York City and began to support herself through domestic employment. In 1843 she left NY and changed her name to Sojourner Truth. She travelled and preached, sang, debated, and eventually was more formally introduced to the concept of abolitionism in a Northampton Massachusetts community, and spoke for the movement around the state. This movement also promoted women’s rights. She met with abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas, David Ruggles, and William Lloyd Garrison.

In 1850, Truth was beginning to participate more in the women’s rights movements, continuing to appear at Suffragette gatherings the rest of her life. While attending an Ohio Women’s Rights convention, she gave her famous “Ain’t I a woman?” speech, which was, unfortunately, altered by Frances Gage 12 years later. Gage giving her a southern slave dialect. In her speech she challenged the notions of racial, and sex based inferiority and inequality by reminding listeners of her strength and female status. Her involvement with the Women’s Rights movement caused a split between her and Douglas, who believed suffrage for black male slaves should come before women’s rights, while Truth believed they could be done simultaneously.

At the beginning of the civil war, Truth aided black men involved in the war. After the war, she was invited to the White House, and became involved in the Freedmen’s Bureau, where she helped former slaves gain employment. While in DC, she was involved in movements that opposed segregation, and in 1860 she won a lawsuit after a streetcar conductor violently tried to keep her from riding.

If you would like to learn more about the life of Sojourner Truth, here are some links below:

#i love women#loving women#women#loving womyn#celebrating women#herstorical women#women in herstory#women in history#herstory#herstorical black women#black women in herstory#historical black women#black feminism#herstorical black womyn#black womyn in herstory#ain’t i a woman#sojourner truth#womanism

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selection from “Herstoric Moments,” by Valerie Mason-John, in Talking Black: Lesbians of African and Asian Descent Speak Out, ed. Valerie Mason-John, 1995.

Raving

Although poetry events, performance nights, books and other publications have added to the multi-faceted character of [British] Black lesbian life, nightclubbing has also been an important source of our culture. Club nights run by Black lesbians have provided a safe haven for many, especially those who find it alienating in predominantly white clubs. Such clubs are a response to the racism we have experienced on the lesbian and gay scene, from being overtly denied entry into venues, to reggae, calypso and bhangra not being played.

Blues parties originate from the African-Caribbean heterosexual community; in the lesbian community they are run predominately by women of African-Caribbean descent. These take the form of a party held in a house, where there is a door charge, a sound system with DJs and a bar. They are frequented by lesbians of both African and Asian descent and by a few white women. Blues parties for Black lesbians have existed in Britain since the 1970s, often in cities where there may have been no other Black lesbian groups, poetry events of performances. Although some people think of them as drunken, smoky affairs, they have provided an essential source of networking, a place where Black lesbians could come together and relax. During the early 1990s Paradise, a nightclub which rented out its space to lesbians and gays, introduced a night called ‘Asia’. Asia was attended by many lesbians of Asian and African descent, and DJs like Ritu played bhangra, new world and disco music.

Shakti has also provided venues for lesbians and gays of Asian descent, where bhangra and other types of Asian music are provided for the clientele. Lesbians of African and Asian descent have also organized one-off events in women’s centre, but sadly such occasions are now few and far between. in London Black lesbian Blues parties are rare--once every four months--and venues are becoming harder to find. DJ Yvonne Taylor, part of the sound system Sistermatic, who were active in the 1980s, believes that because of the lack of Black women-only venues Black lesbians are raving on the mixed Black gay scene.

In 1994, London boasts three venues which are predominately Black: Shakti and the Pressure Zone are for Black gay men/women and their friends, and Shugs is women-only but predominantly Black. Occasionally groups like the Black Experience will hold parties for Black gay men and women, and female DJs like Sister Culture, Ritu and Levi will organize nights for women. Outside of London, places where many Black lesbians and gay men attend are even harder to find.

#lgbtq history#black history#black lgbtq history#asian history#asian lgbtq history#britain#valerie mason john#european history#european lgbtq history#women of color

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Series: 31 Goddesses

Goddess #27: Mother Mary

Origin: Nazareth, Israel

Mother Mary is believed to be a 1st century Galilean Jewish woman who became the virgin mother of Jesus the Christ. Her name in the original manuscripts of the New Testament was based on the original Aramaic, translated as Maryam or Mariam.

She is also known in Christianity as the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Mary, the Mother of God, and Our Lady. She was also called ‘Mary, Queen of Heaven’ and ‘Mary, Queen of the Angels’, both very ancient titles of the widely worshipped Great Goddesses in Africa and the Near East.

Mary is celebrated around the world as the Divine Feminine by millions of people, many of them Catholics. Those who are devoted to Mary, honor Her as the mother of Jesus. The Blessed Virgin Mary is known as the dispenser of mercy, the ever patient mother, and protectress of humanity, and special protectress of women and children.

Herstorically, with the rise of Christianity, the Goddess slowly disappeared from western culture. Officially, the Catholic Church teaches that Mary was mortal and is not a Goddess, but despite this official position, many Catholics honor Mary as a Goddess. Other Catholics revere Mary as Mother of Jesus, but not as divine.

Visions of the Virgin Mary have appeared to thousands of people around the world. Her sacred shrines are at Lourdes in France and Guadalupe in Mexico, as well as many other places.

Her symbols are the sun (or yellow/gold items) and rosary beads.

One of the most beloved images associated with Mary is The Black Madonna. Shrines of The Black Madonna attract thousands of worshippers each year. The Black Madonna is revered throughout the world, particularly in France, Poland, Italy, and Spain.

For many European Christians, the blending of their ancient Goddesses with the Blessed Virgin Mary has been a well-accepted fact of their faith for centuries, there is no conflict. The Holy Black Madonna, (originally Goddess Isis) be She called Mary, or Kali, or Diana, embodies all the aspects of Female Divinity for many millions of people. Mary’s blessings and intervention are still sought daily by millions who pray to the Mother.

Her Legacy: Great Mother energy, purity, devotion, protection, nurturing, belief in miracles, honor your emotions, unconditional love and forgiveness, healing through releasing tears.

May we connect to the Divine Feminine within us and remember who we are.

Picture 1: Egyptian Goddess Isis (Auset) suckling Horus (The original Virgin Mother & Black Madonna)

Picture 2: Mother Mary and Jesus the Christ (Christian Black Madonna)

0 notes

Link

[VIDEO] If you missed it live, here's the link to Rev. Jim Lawson's powerful, Black radical historical and herstorical tribute to Congressman John Lewis. Rev. Lawson contextualized Congressman Lewis's activist roots and reminds all of us that he was one of many Black men AND women who put their lives on the line for racial justice in Apartheid Jim Crow South in the U.S. Born in 1928 (91-years old), Rev. James Lawson is a living legend who was (and still is) a leading theoretician and strategist of radical non-violence. He is the embodiment of liberation theology. Captions are available.

0 notes

Photo

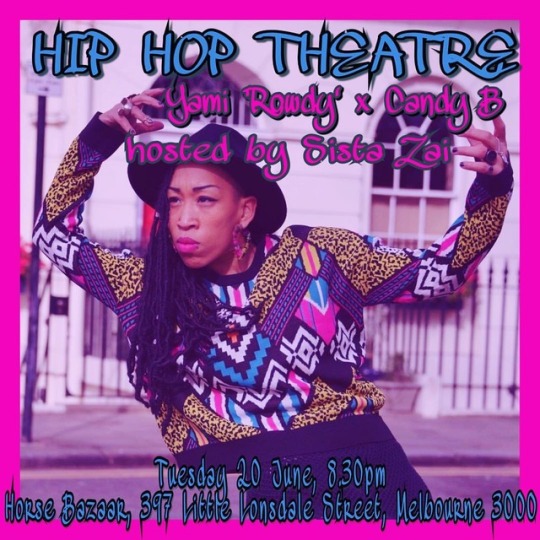

ABOUT THE EVENT Join your host, SISTA ZAI ZANDA (Hip Sista Hop radio show, Pan Afrikan Poets Cafe), at Horse Bazaar - Melbourne's dedicated home of local Hip Hop and Japanese Tapas for a conversation over dinner about Hip Hop Theatre. We are joined by the originator of the Hip Hop Theatre genre in Australia (CANDY BOWERS) and UK's First Lady Of Funk (YAMI 'ROWDY' LOFVENBERG). What are the herstorical foundations of Hip Hop Theatre? How have our two speakers contributed to the development of the form in their respective countries? What is the significance of the form for decolonising theatre? A BIT ABOUT YAMI 'ROWDY' LOFVENBERG UK’s First Lady of Funk has over 19 years’ experience in Streetdance and Funkstyles as a dance artist, teacher and hip hop theatre creator. Yami is currently lecturing at the University of East London and has produced and performed for various shows including: the 2012 Olympics Opening Ceremony, Breakin Convention, Theatre IS, Dare 2 Dance, and Battle of the Year Germany. Yami is a seasoned teacher both in the UK and internationally; with her company Passion and Purpose she curated Project Sonrisa, a community funded project in Colombia where she taught disadvantaged children and local dance teachers. Rowdy’s love, dedication and passion for funk styles across the UK’s hip hop community has earned her place as one of the UK’s finest dancers and a positive role model for young women. A BIT ABOUT CANDY BOWERS Candy Bowers is a poet, writer, actor, playwright and producer. The Co-Artistic Director of Black Honey Company, Candy makes fearless, sticky work that delves into the heart of radical feminist dreaming. Her credits include Hot Brown Honey, Sista She, Australian Booty and MC Platypus and Queen Koala’s Hip Hop Jamboree. A BIT ABOUT PAN AFRIKAN POETS CAFE Established in 2015 by Sista Zai, the Pan Afrikan Poets Cafe is the home of new, cutting edge and classic Afrikan literature. Sista Zai created this project to celebrate Afrika's rich literary legacy and diverse storytelling traditions. (at Horse Bazaar)

0 notes

Text

Women: Historically the Greatest

March officially marks the celebration of Women’s History nationwide. Thank God it’s Women’s History Month (TGIWHM?!). According the Library of Congress’ archives, Women’s History Month originated as a week-long national celebration on March 7, 1981. Congress continued to pass joint resolutions that acknowledged a week in March as “Women’s History Week”. The National Women’s History Project petitioned for the week to be extended to a month-long celebration, which Congress passed in 1987. Since then, March has been used to highlight the triumphs, struggles, and achievements of boss ladies all across the nation and all throughout history. It will always be important to acknowledge the contributions of marginalized groups in America. It is even more important to acknowledge those that continually go underrepresented which is why I’ve chosen some of my favorite herstorically great Black women.

Let’s start with one of my favorite activists of all time. Meet Mary Ann Shadd. She was a strong emigrationist voice in the 1850’s. She grew up in an abolitionist family and worked tirelessly to advocate for Black emigration. She spoke at The National Emigration Convention in 1854, which caused controversy because women were not usually permitted to speak at black conventions. She was known for holding black leaders accountable for lack of intersectionality in their movements. I love her because she was never easily deterred. Mary Ann Shadd was a trailblazer and she teaches us the lesson of fearlessness.

I can’t talk about historical Black women without mentioning my role model, Shirley Chisholm. Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was a politician, educator, writer, and boss. She was the first Black women to be elected to the United States Congress in 1968, but her political achievements do not stop there. She was the first Black candidate for a major party’s nomination for the President of the United States and the first woman to run for the Democratic Party, period. This means she paved the way for every African American and female politician to come after her. She advocated for Black women in leadership which is something that we still have to push today. Thank you, Shirley Chisholm, for your crucial groundwork, and teaching us the lesson of how important our service truly is.

Lastly, I want to highlight someone who continues to make strides each and everyday that have never been made before. Misty Copeland is a dancer who has made history very early in her life. On June 20, 2015, Copeland became the very first African American woman to become a principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre. She is more than just a ballerina. She acts as a rolemodel, an author, and a spokesperson. She did not let the fact that she doesn’t have the “traditional” ballerina’s body stop her from following her dreams and becoming a beast in the industry. Misty Copeland teaches us the lesson of being unapologetically great through self expression.

There are so many more Black women who have made countless contribution to this country and to the world, at large. In honor of Women’s History Month, let’s all strive to join them!

0 notes

Text

Madam CJ Walker (December 23, 1867 - May 25, 1919)

Sarah Breedlove, known by the name Madam CJ Walker, was born in Delta, Louisiana on a plantation to which her parents were enslaved before the end of the Civil War. She was their 5th child, but the first child born free after the Emancipation Proclamation. Becoming an orphan at 7 years old, her and her sister Louvenia worked in the cotton fields of Delta and the nearby Vicksburg, Mississippi.

At age 14, to escape abuse from her brother-in-law, she married to a man named Moses McWilliams (having a daughter with him, A’Lelia, in 1885) and eventually became a widow at age 20. She moved with her daughter back with her brothers who had become barbers making $1.50 a day, and made enough to send her daughter to school. In the 1890s, Sarah began to suffer from an ailment that caused her to begin losing her hair. After consulting her brothers, she used many products to try and help her situation, and her brothers gave her products made by one Annie Malone, a black entrepreneur.

Moving to Denver Colorado to become a sales agent for Miss Malone, she married one Charles Joseph Walker. Afterwards she changed her name to “Madam” CJ Walker, and started selling her own line of hair products for American black women. Her husband, working in newspaper advertisements, helped promote her products, though eventually the two divorced. After the divorce, she moved to Indianapolis and opened a manufacturing factory for her products, employing 40,000 black women and men in the US, central America, and the Caribbean, founding the “National Negro Cosmetics Manufacturers association” in 1917.

Fun facts

Upon moving to Indianapolis, she donated $1,000 (about $30,000 in today’s amount) to the first YMCA open to black Americans, and funded scholarships for women to attend Tuskegee Institute

She is the first black woman millionaire in the US

She established clubs for her employees so they could give to their communities

You can learn more about Madam CJ Walker through the following sources:

https://madamcjwalker.com/about/

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/madam-cj-walker

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.history.com/.amp/topics/black-history/madame-c-j-walker

#i love women#women#loving women#loving womyn#celebrating women#herstorical women#women in herstory#herstory#women in history#Madam CJ Walker#black women in herstory#black women in history#herstorical black women#historical black women

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#dasia taylor#womyn making herstory#black women making herstory#black womyn making herstory#black women making history#women making history#herstoric#herstorical#historic#historical#medical discoveries by women#women in medicine#womyn in medicine#i love womyn#i love women

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black British Lesbian History

Selection from “Herstoric Moments,” by Valerie Mason-John, in Talking Black: Lesbians of African and Asian Descent Speak Out, ed. Valerie Mason-John, 1995.

The movement

A separately organized Black lesbian movement is perhaps the response to our exclusion from the Black heterosexual world, the women’s liberation movement and the white lesbian and gay community. The herstory of lesbians which has been uncovered, recorded and celebrated is predominantly about white middle-class women. In fact, it is dead white lesbians who dominate the bookshelves: Radclyffe Hall, Djuna Barnes, Vita Sackville-West, Eleanor Roosevelt and Romaine Brooks are just a few of the names which we repeatedly come across when searching for lesbian herstory. The documented rise of the women’s movement during the 1970s mainly records the contribution of white women, including some white lesbians, through photography and writing. Although the 1980s have witnessed the beginning of the documentation of Black lesbian literature, it has been normally by women of African descent from the USA. Therefore, it has been important for Black lesbians living in Britain to begin documenting their own contribution to the movement before it is lost.

The herstory of the Black lesbian movement is typified by the struggle to have our gender, race and sexuality placed on the agenda. The Black political movements of the past--Garveyism, Pan-Africanism, the Black Power and civil rights movements--were all dogged by debates, splits and silence around gender and sexuality. Gender was most definitely not a priority issue, and the consideration of sexuality was completely ignored. Due to such conflict it was felt among some Black people that Black women could not afford to be separatist over certain issues and debates, because of the need to work together with Black men to overcome racism. In fact, it can be said that organizations such as Manchester Black Women’s Co-op and Southall Black Sisters, who spearheaded the ‘Stop the SUS’ (Suspect Under Suspicion) campaign; Zanus Women’s League; East London Black Women’s Organization; the Organization of Women of African and Asian Descent; and other Black lesbian groups were all a response to the years of struggling to be recognized as women in the Black political movement, as lesbians in the Black feminist movement and as Black in the women’s liberation movement and the lesbian and gay community.

Black lesbians were isolated, they had lost their allegiances among white women and with the Black heterosexual community. A whole feminist herstory had been written excluding the contribution of Black women. White women, whether lesbians, feminists or lesbian feminists were not interested in American chemical companies polluting first-nation countries, or in the illegal mining in Namibia; in fact, they were only concerned with their immediate needs.

Although there has been a separate movement, Black lesbians have always been part of the wider Black, feminist and lesbian struggles. Many were always active in the Black liberation movement and others took part in Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW), the women’s liberation movement, the Gay Liberation Front, antinuclear campaigning (Greenham Common) and Reclaim the Night marches, between the late 1960s and 1980s. Our herstory has been shaped by our oppressions. However, Black lesbians have risen above their oppressors, and achieved monumental feats, despite the odds stacked against us.

African and Asian unity

Although the Black political movement had initially brought men and women together, Black women, unhappy with their declared position in the movement, found the need to organize autonomously, and used the opportunity to forge links with other Black women they had met in the global Black struggle. As a result, the Organization of Women of Africa and African Descent (OWAAD) was founded in 1978. However, during its first year, it was argued that if OWAAD was to address issues concerning all Black women effectively, women of African and Asian descent should stop organizing separately around the issues of racist attacks, deportations, Depo-Provera and the question of forced sterilization of Black women in Britain. This shift towards forging links together was sealed in 1979 when OWAAD changed its named to the Organization of Women of African and Asian Descent. As the first documented and cohesive national network of African and Asian women, it united Black women from all over Britain, and had a profound influence on Black British women’s politics. To ensure links were maintained, a newsletter (FOWAAD) was printed.

[/]

However, rifts soon began to appear in the organization, and one of the major splits occurred over the issue of sexuality. Black lesbians, although they were most definitely at the forefront of the organization, found themselves to be invisible. Some remained in the closet while others were continually silenced, and those who were publicly outed caused a furore. From its outset there was a noticeable absence of debate around this issue; sexuality was perceived as being too sensitive to speak about publicly. The prevailing opinion was: ‘How could members wast time discussing lesbianism, heterosexism and bisexuality when there were so many more pressing issues?’ One of the first out and visible Black lesbians in public and the media, Femi Otitoju, remembers the conference which caused the damage, ‘A woman announced, there is no space for Black lesbians, so let’s have a workshop over here.’ She remembers some Black women being abusive and hostile, and hurling insults. She recalls: ‘Some women stood up and said we’re lesbians and we’re offended and upset. I remember thinking, shush, you damn fools.’ An ignorance of the background to the struggle and/or a hostility towards feminism from the newer members, together with the failure of the organization to take on board the differences, meant that OWAAD had a short life, and it folded in 1982. Although members of OWAAD failed to unite with each other over some issues, it was an important chapter in Black women’s herstory. It campaigned against immigration authorities and virginity tests at ports of entry, it demonstrated against state harassment, battled against expulsions in education and fought many unjust laws. OWAAD for all its faults had much of the vibrancy and energy a Black movement needed.

Positive results came out of the rise and fall of OWAAD. Black lesbians belonging to the organization came together in 1982 and formed their first group, called the Black Lesbian Group, based in London. it is claimed that Black women travelled from Scotland, Wales and all over England to attend the fortnightly meetings. A fares pool was provided by members for women who needed expenses for their travel. However, the group struggled for survival. It initially asked to meet at Brixton Black Women’s Centre, but was denied access because some of the workers were concerned that a lesbian group on the premises would add to the hostility it was already experiencing as a Black women’s centre. Black lesbians of mainly African descent and some of Asian descent eventually found space at the now-defunct centre, A Woman’s Place, based in central London.

OWAAD’s driving force

Members of Brixton Black Women’s Group (BBWG) were part of the motivating force (along with other politically active Black women around Brtiain) which founded the national organization, OWAAD. BBWG was set up in 1973, in response to redefining what the Black and feminist movements meant to them. Its members were an amalgamation of Black women from the women’s and the Black liberation movements. In its early days the group’s politics was influenced by socialism. Some women preferred not to call themselves feminists because it would link them to the women’s movement which had many racist attitudes. Others identified as feminists, but emphasized that feminism stretched beyond the narrow concepts of white middle-class women. During the early 1980s the group had a strong core of members who identified as Black socialist feminists. Although the question of lesbianism featured quite low on the agenda, many of the BBWG founding members were lesbians.

The group met at the Brixton Black Women’s Centre, which was established by the Mary Seacole Group. This group aimed to provide a meeting space, gave support and advice on housing, social security and to mothers. Skills such as sewing, dress-making and crafts were shared. Although the crafts group collapsed over an argument about their political posture, the BBWG survived, and opened up the centre’s doors to the public in 1979. This group was involved in various campaigns which affected every aspect of being a Black woman.

Black lesbians worked at the centre along with Black heterosexual women, and continued to serve all Black women until 1986, when the workers learnt they had been working in a condemned building, and suffered a cut in funding. This marked the end of an era; all that is left is a derelict building with an unfinished mural of Black women working together. ‘Groups like Brixton BWG were just one of the strands which, when woven together, helped bind the political practice of the Black community as a whole. They were in many ways simply a continuation of the Black groups which had existed ever since our arrival after the war.’[1] There were thirty or more groups like the BBWG (with a strong input from Black lesbians) scattered throughout Britain during the 1970s and early 1980s.

Renaissance Black lesbians

In 1984 a group of white lesbians set up Britain’s first lesbian archive, to preserve the contribution lesbians had made to British culture. During the 1970s Black lesbians had taken part in many campaigns which affected women and Black people, but this was not being recorded. Similarly, in setting up this archive, the contribution made by Black lesbians was overlooked. The archive reinforced the white-only image of lesbians through the books and information it collected, by the workers and volunteers it employed, and through its membership. Five years after it opened, a Black employee, Linda King, was taken on to try and redress this imbalance. She explored the relevance of the Lesbian Archive and Information Centre to the Black lesbian community, and how it could be improved. During her four-week contract, she collected interviews, transcripts and photographs of Black lesbians (some of which are only available to Black lesbians), and compiled a report. One of the points raised in the interviews was the fact that Black lesbians had contributed to the intellectual and cultural interests of all lesbians in Britain.

Making our mark in the 1980s

The 1980s was a decade in which Black lesbian activity flourished throughout Britain. After the first Black lesbian group was set up in 1982, Black lesbians took the initiative to organize groups, meetings and conferences on a grand scale. During 1983 a Chinese lesbian group was launched after three lesbians of Chinese descent met for the first time at a conference on lesbian sex and sexual practice. In 1984 the ‘We Are Here’ conference marked the first time that Black women had come out publicly as Black feminists. An organizer, Dorothea Smartt, recalled: ‘It was unashamedly a Black feminist conference where Black lesbians were welcome.’ The conference planning group was open to all Black women including Black lesbians.

From discussions at the conference several initiatives were launched: an incest survivors’ group; a Black women writers’ network; a mixed racial heritage group; ‘We Are Here’ newsletter and the Black Lesbian Support Network (BLSN). The BLSN offered advice, information and support to Black women questioning their heterosexuality. it also collated articles by and about Black lesbian lifestyles from all over the world. It was forced to close in 1986, as the exhausted volunteers moved on to do different things in the Black lesbian community. However, the collated articles are available from the Lesbian Archives in central London. The ‘We Are Here’ newsletter covered many issues, including health, incest, definitions of Black feminism, Black lesbian mothers and reports about such ongoing national and global campaigns as anti-deportation fightbacks and nuclear testings in Africa. This also folded in 1986, a year which saw the closure of many women’s, gay and lesbian, Black and left-wing groups in London. The abolition of the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1986 initiated a period of severe cutbacks in funding for many community-based groups.

However, despite the effects of a Thatcherite government, some groups did spring up and survive. During the mid-1980s a Black lesbian group was established at Waltham Forest Women’s Centre, but folded after two years; and in the London borough of Camden, a Black lesbian group which was set up next to the Camden lesbian project in 1985, still exists today. In this same year several black lesbians were involved in the establishment of the Lesbians and Policing Project (LESPOP); this project was forced to close in 1990 due to a complete cut in its funding. Black lesbians of Asian descent also launched a group, but this folded before the new decade. Funding was secured for a research project on Lesbians from Historically Immigrant Communities, which included testimonies from lesbians of African and Asian descent. Although the work was never published it can be found in the Lesbian Archives. Most of the groups which were set up for Black lesbians during the first half of the decade existed in London, but there were groups in other parts of Britain.

The impact and effect of these groups (with a donation of £11,000 from a white working-class lesbian weekend) culminated in Zami 1, the first national Black lesbian conference to be held in Britain. In October 1985 over two hundred lesbians of African and Asian descent flocked to London to attend this herstorical event. It was a natural high in itself to be in one space with so many other Black lesbians, and it was a proud moment for those Black lesbians who had been part of the struggle for visibility and recognition during the preceding decade. Delegates discussed issues of coming out in the Black community, disability, prejudices between lesbians of African and Asian descent and various other topics. As with all conferences there were differences of opinion, in this case over the question of who was and was not Black. However, such debate was not surprising when so many Black lesbians from all over Britain had come together for the first time, the political thinking of OWAAD, and of London, had not necessarily filtered its way all over the country.

Zami 1 was and still is one of the greatest achievements of Black lesbians. It paved the way for further conferences, gave confidence to those Black lesbians who were frightened of coming out, and most of all it told the general public that Black lesbians do exist, and in numbers. In the same year Black lesbians were instrumental in setting up Britain’s first lesbian centre in Camden, London, and during the latter part of the 1980s, Black lesbian groups were established in Birmingham, Manchester and Bradford, together with a group for Black lesbians over forty and a group for younger Black lesbians in London.

At the turn of the decade (April 1989), Black lesbians organized the second national conference, Zami II, in Birmingham. Unlike the first conference, Zami II was open to other Black lesbians with one or both parents from the Middle East, Latin America, the Pacific nations, to indigenous inhabitants of the Americas, Australasia and the islands of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, along with those of us who are descended from Africa, Asia and its subcontinent. Over two hundred women came together and debated the issues of sex and sexuality, sexual relationships between Black and white lesbians, motherhood and many other issues. From this conference a group of women imitated a group for lesbians and gays of mixed racial heritage (MOSAIC), which still exists today, and which held its first conference in 1993 in London. In 1991 two Black lesbian groups were set up in Nottingham and Bristol, and in 1992 a day-long event was held where Black lesbians could discuss the issue of safer sex and HIV and AIDS.

During the early 1990s the rise of Black lesbian activity reached a plateau, and is now beginning to dwindle and stagnate. Although 1992 saw another Black lesbian conference in the North, only a few groups have been founded. There have also been Zami (events of Black lesbians) days in Birmingham in 1993 and 1994.

Organizing with Black gay men

To a lesser extent Black lesbians have also organized with Black gay men. 1981 is a landmark for Black lesbians and gay men organizing together, as it was the year when the Gay Asian Group became the Black Gay Group. Although the group was initially dominated by men, women soon became a more visible presence when it renamed itself the Lesbian and Gay Black Group in 1985. This group went on to secure funding for a Black Lesbian and Gay Centre based in London. The project survived seven years of looking for sufficient funds and suitable premises, but in 1992 the centre was finally launched, and two years later it still exists as the only centre in Britain serving Black lesbians and gay men exclusively.

In 1988 Shakti, a network for South Asian lesbians, gays and bisexuals was set up in London. Since then, other Shaktis have sprung up in major cities, providing a fundamental resource for the Asian community. In 1990 Black lesbians and gay men came together to organize the sixth International Lesbian and Gay People of Colour conference in London, when over three hundred people came together from all over the world to discuss issues which concerned them. During this same year Black lesbians and gay men came together and formed Black Lesbians and Gays Against Media Homophobia (BLAGAMH), which led to one of the most successful campaigns against the Black media in Britain this century. This had centred on the ferocious attack made against lesbians and gay men by Britain’s most successful Black newspaper, The Voice. During the last three months of 1990, it carried malicious and homophobic stories, including a report on the Black British footballer Justin Fashanu, and printed Whitney Houston’s remark that she was not a ‘Lesbo’. The paper’s columnist, Tony Sewell, wrote: ‘Homosexuals are the greatest queerbashers around. No other group are so preoccupied with making their own sexuality look dirty.’ BLAGAMH, along with the support of the National Association of Local Government Officers (NALGO), initiated a successful boycott of The Voice, instructing local authorities not to advertise in the newspaper. After almost a year’s battle, BLAGAMH won a full-page right-to-reply. The Voice also promised to adopt an equal opportunities policy and ensure positive coverage of lesbian and gay issues, a commitment which the newspaper has so far upheld. BLAGAMH continues to monitor the Black community, and has challenged ragga artists like Buju Banton and Shabba Ranks over their use of misogynistic and homophobic lyrics.

That same year (1990) saw the establishment of Orientations, a group for lesbians and gay men of Chinese and South Asian descent. Groups have also been formed by Black lesbians and gays in Manchester, and, in 1991, by Black lesbians, gays and bisexuals in Bristol. All three groups exist today. The short life of Black lesbian and gay groups is typical of the whole lesbian and gay community: as soon as one group disappears, another emerges.

#lgbtq history#black history#black lgbtq history#asian history#asian lgbtq history#valerie mason john#lesbian history#britain#women of color

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black British Lesbian History: Arts, Literature, and Media

Selection from “Herstoric Moments,” by Valerie Mason-John, in Talking Black: Lesbians of African and Asian Descent Speak Out, ed. Valerie Mason-John, 1995.

Art and literature

Since the late 1970s here has been some visibility of Black women’s writing in Britain. The majority of it has been by heterosexual women of African descent living in Africa, the Caribbean and the USA. The late Audre Lorde, American-born Caribbean poet, novelist and essayist, was perhaps our first Black lesbian icon here in Britain. Since then Asian lesbian writer Suniti Namjoshi and African-Scottish writer Jackie Kay have come to the forefront of Black writing in Britain. Their work is acclaimed both nationally and internationally. Writers such as Barbara Burford, Maud Sulter and Meiling Jin have also made inroads into established British and women’s publishing houses.

The feminist publisher, Sheba, currently run by Black lesbians, is one of the few women’s publishing houses which has made a strong commitment to producing the work of Black lesbians in Britain. However, the lack of interest from most publishing houses has meant that Black lesbians in Britain have created their own initiative to publish the work of all Black women, including themselves. The Black Womantalk collective is an example of this. In 1990 a Black lesbian, Maud Sulter, set up Urban Fox Press, which published Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity, an anthology of the work of Black women of all sexualities. Sulter has since achieved the distinction of having her art work purchased for the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Festival Hall. While I was writing this chapter, Zamimass, a Black lesbian political organization, curated the first-ever exhibition in London by Black lesbians only. Although it was regionally based it marked the beginning of sharing our creativity publicly. Zamimass hope its next exhibition will be a national one, bringing together the work of Black lesbian artists from all over Britain.

Our media

We have also contributed to newspapers and magazines. Outwrite, an anti-racist, anti-imperialist women’s monthly, was set up in 1982 by a group of mainly Black women, some of whom were Black lesbians. It covered stories about women all over the world, including Black lesbians. After seven years it folded, a casualty of a dissipated women’s movement, lack of money and worn-out collective members. Spare Rib, the longest-running feminist publication and most widely known in the rest of the world, was founded in the 1970s. The collective went through many changes, being initially composed of white middle-class women and ending up as an almost exclusively Black female heterosexual collective. However, during its life Black lesbians were involved in the collective, and continued to contribute articles regularly until the monthly magazine disappeared overnight in 1993.

The first and only magazine to talk about sex and sexuality, Quim, was founded by a group of Black and white lesbians in 1989. Despite the fact that it celebrated all lesbian sexuality, it was heralded as a soft porn and sado-masochistic (SM) publication. Although a Black lesbian was involved in the initial concept of the magazine, very few Black lesbians have been published in it. Indeed, this quarterly periodical has predominantly served the white lesbian SM community. However, in 1994, Quim was guest-edited by a Black lesbian performer and writer Leonora Rogers-Wright, and the majority of the magazine was dedicated to Black women speaking out. For the first time in British Black lesbian herstory, women of African and Asian descent modelled in numbers for Quim magazine, posing with dildos, handcuffs and ropes, and wrote what could be considered SM and bondage short stories. In 1991 British Black lesbians of Asian descent attended the first Asian lesbian conference in Bangkok, and set up a quarterly publication, Asian Lesbians Outside of Asia (ALOA). Although the group still exists, a publication has not been produced during the past year.

In response to the lack of literature about Black women, a new newspaper, Diaspora, by and about women of colour was launched on International Women’s Day, 8 March 1994. It is run by a collective of Black lesbian and heterosexual women who hope to cover a wide range of issues concerning all Black women.

Expressing our sexuality

Performers and artists have also been a vital source of Black lesbian culture. Through song, poetry, dance and plays, Black lesbian sexuality has been celebrated. The a cappella group Sistahs in Song (active in the 1980s) and performers like Parminder Sekhon and Michelle Asha Warsama are only a few of the many talented women who have been visible through their work. In 1982 the Theatre of Black Women was set up by Black lesbian and heterosexual women, with the aim of giving a voice to the Black female performer. Several of the group’s plays were written by Black lesbians, including Jackie Kay. The group disbanded in the latter part of the 1980s due to a loss of funding. Sauda, a group of African-American and African-Caribbean lesbians based in Britain, created prestigious events, featuring all women of African descent, during 1992 and 1993.

#lgbtq history#black history#black lgbtq history#asian history#asian lgbtq history#britain#valerie mason john#women of color

5 notes

·

View notes