#ferris bueller’s day off scene with cameron staring at the little girl in the painting but it’s feyd-rautha staring at the bean

Text

rip house harkonnen you guys would have loved the bean

#ferris bueller’s day off scene with cameron staring at the little girl in the painting but it’s feyd-rautha staring at the bean#dune#dune part two#dune part 2#house harkonnen#feyd rautha harkonnen#baron harkonnen#rabban harkonnen#giedi prime

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

about me ! ⋆˙⟡♡

i’m a british teenager who enjoys film studies and english literature. i love writing poetry and i talk far too much. people say it’s because i have such an imagination and that a lot goes on in my head that i don’t process. i’m bad at processing my thoughts, so tend to just live in the moment. i feel most like myself when i’m writing, acting, or watching films, and i try to find myself or others in everything around me. i consider myself to be somewhat of a neil perry from peter weirs dead poets society. i also consider myslef as somewhat of a charlie kelmeckis (the perks of being a wallflower) and a jo march (little women). i think if i were a song it would be forever young by alphaville, i can imagine that being my song in an 80s coming of age/comedy film. i mean it is my favourite song of all time now, but real life in 2024 is nowhere near as cool. on the topic of films, my favourite scene in cinematic history is neil perry’s monologue scene in dead poets society where he talks about his dream of being an actor. however, the art museum scene in ferris buellers day off with the instrumental of the dream academy’s please please please let me get what i want is my favourite moment in cinematic history without speech. in particular, when cameron is staring at the girl in the painting and seeing himself in her. the whole idea is that the more he looks at the girl in the painting the less she becomes and the less he is able to see, he fears that the more people look at him he will get the same fate as the painting. to finish off some of my vague favourites, my favourite writing of any sort whatsoever is sylvia plaths idea of the fig tree analogy in the bell jar, i reference it in almost everything i write, thus it’d be wrong not to give it its rightful mention here. if you have not read the bell jar, or know if this analogy i highly recommend. i’ll show you an extract about the analogy beneath.

“i saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. from the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. one fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor” and so on.

my favourite films ☆

౨ৎ dead poets society (1989)

౨ৎ the perks of being a wallflower (2012)

౨ৎ ferris buellers day off (1986)

౨ৎ stand by me (1986)

౨ৎ it chapter 1 (2017)

౨ৎ bridge to terabithia (2007)

౨ৎ beautiful boy (2018)

౨ৎ mrs doubtfire (1993)

౨ৎ juno (2007)

౨ৎ scott pilgrim vs the world (2010)

౨ৎ grease (1978)

౨ৎ wonder (2017)

if you liked any of those you should totally consider following my letterboxd @bobbieisnotcool !

my favourite songs right now ♫

౨ৎ forever young by alphaville

౨ৎ friends will be friends- live in budapest by queen

౨ৎ i know you by faye webster

౨ৎ her majesty takes 1-3 by the beatles

౨ৎ silver springs live 23.5.1997 by fleetwood mac

౨ৎ anyone else but you by the moldy peaches

౨ৎ take on me by aha

౨ৎ pale blue eyes by the velvet underground

again, if you liked any of those you should totally follow my spotify linked below!

“we accept the love we think we deserve”

#girlblogging#girlhood#about myself#dead poets society#the perks of being a wallflower#hell is a teenage girl

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lessons Learned From Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

III. How to experience spontaneous, self-directed learning

Frankly, I don’t believe that Ferris, Cameron and Sloane would have spent their ‘day off’ better in school. Consider everything they pack into it: they ascend to the top of Willis Tower and observe the ant-like movements of workers 1400 feet below; they stare at the frenzied floor of the stock exchange and learn the sign-language of its traders; they take in a baseball game at Wrigley Field at the exact moment they should be enduring a gym lesson. Far from blowing learning off, Ferris’s rich schedule of activities achieves anything you could want for an educational field trip. The point is well made in a scene filmed inside the Art Institute of Chicago in which Ferris, Cameron and Sloane hold hands with a group of much younger children who are there with their teacher – everything they do mirrors the curriculum being delivered to their campus-bound classmates, the difference being how much more engaged they are.

youtube

John Hughes offers a comparable opportunity to the film’s audience. During the same gallery sequence, lengthy shots of masterpieces by Edward Hopper, Amedeo Modigliani, Jackson Pollock and Pablo Picasso fill the screen to an instrumental version of the Smiths’ song ‘Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want’. There is no clear motive to this montage: it doesn’t advance the film’s plot or match the frenetic pace of its comic hijinks; the art is celebrated for its own sake. Perhaps Hughes is doing for Ferris Bueller’s Day Off what galleries do for cities the world over, providing a respite to the bustle and purpose of everything else. In narrative terms, the scene is a prime example of what Timothy Morton means when he says that a ‘middle’ (development) is characterized by a slow, meditative pace and a feeling of absorption. In educational terms, the scene supports a claim for the value of the unplanned (much of it was improvised) or the apparently irrelevant. It can be frustrating for English or Arts teachers to vindicate their content in ‘lessons planned for … audit and accountability’, sacrificing ‘the unfinalisable struggle for meaning’ at the mendacious altar of ‘the easily-measurable’. Art, music and literature are illustrative of the ways in which meaning can be a slippery, mercurial thing; when they appear in an educational context they can also force a distinction between usefulness and value, reminding us that many of the things we place the highest value on are, from a utilitarian perspective, useless: chocolate, wine, sunsets, love. Hughes’s Art Institute sequence invites us to consider the flaws of an education system so staid and inflexible that it requires a ‘day off’ for students to reckon with something powerful enough to influence their perception of themselves and the world around them.

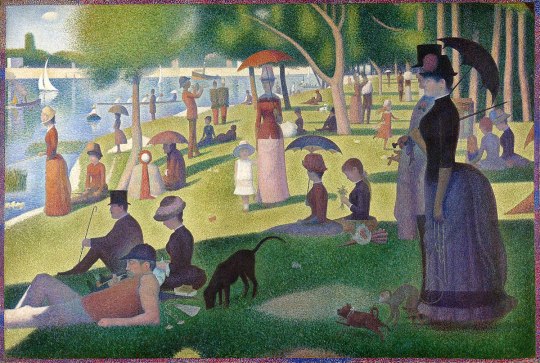

It is just such a reckoning that occurs when Cameron stands alone before Georges Seurat’s pointillist work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. The painting depicts a group of well-to-do people promenading by the banks of the river Seine in the late 19th century, the men in top hats and the women in bustle-heavy dresses. Everyone in the painting seems together yet somehow alone, and a small girl dressed in white stares at the viewer from the centre of the canvas. Cameron fixates on this little girl – she is the only figure in the painting who makes a connection to the world outside its frame, and so the raw perceptive powers of childhood are contrasted against the dulling superficiality of adulthood. A teenager hovering between these two states of being, Cameron’s wrapped expression suggests that he is young enough to identify with the child but old enough to fear the looming demands of adult life. The film cross-cuts between increasingly close shots of his face and that of the girl, who on closer inspection appears to be wailing in distress. Eventually, Cameron’s eyes and the specks of paint on Seurat’s canvas appear in such extreme close-up that they cannot be resolved as themselves – they become abstract details of shape and colour.

It’s an ambiguous but quite moving sequence of film, especially when set inside of a breezy, feel-good comedy. If there’s a point, it may be that Cameron sees his own anxieties reflected in the girl’s anguished face and either he or the audience (or both) are made aware that overwhelming pain can obliterate identity. Hughes alludes to this in an audio commentary recorded for the film’s DVD release:

The closer he looks at the child, the less he sees with this style of painting. The more he looks at it there’s nothing there. He fears that the more you look at him there isn’t anything to see. There’s nothing there. That’s him.

Erik Erikson’s seminal research into identity formation considers that emerging adults experience a dynamic interplay between identity synthesis and identity confusion: while most of us use the process of ‘trying out’ possibilities to determine an internally consistent sense of self, some experience an arrested development in which a fragmented or piecemeal selfhood does not support decision making. On this basis, we might consider Ferris’s play-acting to be an example of normative behaviour leading to identify formation. Cameron, on the other hand, appears to be enduring an atypical crisis: believing himself to be dying from an incurable disease, immobile with anxiety at the wheel of his car, staring in horrified recognition at the deconstructed face of Suerat’s child, he could be said to exemplify what James Marcia calls ‘identity diffusion’: he does not enjoy exploring options in the way that Ferris does, nor does he make a commitment to any of the possibilities lain before him. When an incredulous Ferris asks him to acknowledge all that he’s seen and done on his ‘day off’, Cameron’s laconic response is, ‘Nothing good’.

Perhaps we should resist the temptation to psychoanalyse a fictional character as though he were possessed of a ‘real’ inner life. Cameron has more depth than Ed Rooney, but he’s not Hamlet. Ferris is the character you want to be, but Cameron is who you think you are (or fear you might be). Because you identify with him, there’s a temptation to project your psychology onto him. This might lead to the sobering realisation that you share some of his issues, but it’s worth remembering that Cameron is also a more perceptive individual than his famous friend. It is his depth and sensitivity that awe him when confronted by Seurat’s painting. The moment is almost epiphanic: what could be more absorbing than seeing yourself staring back at you from a hundred-year-old work of art? Ferris and Sloane enjoy their ‘day off’, but Cameron has a life-altering encounter, despite his claim of not having seen anything good. At the end of the film (and in a revealing act of growth) he resolves to confront his authoritarian father. Eleanor Harvey, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, considers there to be a direct link between his experience of the painting and the way the arc of his character resolves: ‘That encounter with the painting … gives [Cameron] courage to understand that he can stand up for himself’. Not a bad lesson to have learned on your day off.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (French: Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte) painted in 1884, is one of Georges Seurat's most famous works. It is a leading example of pointillist technique, executed on a large canvas. Seurat's composition includes a number of Parisians at a park on the banks of the River Seine.

Background

In 1879 Georges Seurat enlisted as a soldier in the French army and was back home by 1880. Later, he ran a small painter’s studio in Paris, and in 1883 showed his work publicly for the first time. The following year, Seurat began to work on La Grande Jatte and exhibited the painting in the spring of 1886 with the Impressionists.[2] With La Grande Jatte, Seurat was immediately acknowledged as the leader of a new and rebellious form of Impressionism called Neo-Impressionism.[3]

Seurat spent more than two years painting A Sunday Afternoon,[4] focusing meticulously on the landscape of the park. He reworked the original and completed numerous preliminary drawings and oil sketches. He sat in the park, creating numerous sketches of the various figures in order to perfect their form. He concentrated on issues of colour, light, and form. The painting is approximately 2 by 3 meters (7 by 10 feet) in size.

Inspired by optical effects and perception inherent in the color theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and others, Seurat adapted this scientific research to his painting.[5] Seurat contrasted miniature dots or small brushstrokes of colors that when unified optically in the human eye were perceived as a single shade or hue. He believed that this form of painting, called divisionism at the time but now known as pointillism, would make the colors more brilliant and powerful than standard brushstrokes. The use of dots of almost uniform size came in the second year of his work on the painting, 1885–86. To make the experience of the painting even more vivid, he surrounded it with a frame of painted dots, which in turn he enclosed with a pure white, wooden frame, which is how the painting is exhibited today at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Island of la Grande Jatte is located at the very gates of Paris, lying in the Seine between Neuilly and Levallois-Perret, a short distance from where La Défense business district currently stands. Although for many years it was an industrial site, it is today the site of a public garden and a housing development. When Seurat began the painting in 1884, the island was a bucolic retreat far from the urban center.

The painting was first exhibited in 1886, dominating the second Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, of which Seurat had been a founder in 1884. Seurat was extremely disciplined, always serious, and private to the point of secretiveness—for the most part, steering his own steady course. As a painter, he wanted to make a difference in the history of art and with La Grand Jatte, succeeded.[6]

Interpretation

Seurat's painting was a mirror impression of his own painting, Bathers at Asnières, completed shortly before, in 1884. Whereas the bathers in that earlier painting are doused in light, almost every figure on La Grande Jatte appears to be cast in shadow, either under trees or an umbrella, or from another person. For Parisians, Sunday was the day to escape the heat of the city and head for the shade of the trees and the cool breezes that came off the river. And at first glance, the viewer sees many different people relaxing in a park by the river. On the right, a fashionable couple, the woman with the sunshade and the man in his top hat, are on a stroll. On the left, another woman who is also well dressed extends her fishing pole over the water. There is a small man with the black hat and thin cane looking at the river, and a white dog with a brown head, a woman knitting, a man playing a horn, two soldiers standing at attention as the musician plays, and a woman hunched under an orange umbrella. Seurat also painted a man with a pipe, a woman under a parasol in a boat filled with rowers, and a couple admiring their infant child.[7]

Some of the characters are doing curious things. The lady on the right side has a monkey on a leash. A lady on the left near the river bank is fishing. The area was known at the time as being a place to procure prostitutes among the bourgeoisie, a likely allusion of the otherwise odd "fishing" rod. In the painting's center stands a little girl dressed in white (who is not in a shadow), who stares directly at the viewer of the painting. This may be interpreted as someone who is silently questioning the audience: "What will become of these people and their class?" Seurat paints their prospects bleakly, cloaked as they are in shadow and suspicion of sin.[8]

In the 1950s, historian and Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch drew social and political significance from Seurat’s La Grande Jatte. The historian’s focal point was Seurat’s mechanical use of the figures and what their static nature said about French society at the time. Afterward, the work received heavy criticism by many that centered on the artist’s mathematical and robotic interpretation of modernity in Paris.[7]

According to historian of Modernism William R. Everdell, "Seurat himself told a sympathetic critic, Gustave Kahn, that his model was the Panathenaic procession in the Parthenon frieze. But Seurat didn't want to paint ancient Athenians. He wanted 'to make the moderns file past ... in their essential form.' By 'moderns' he meant nothing very complicated. He wanted ordinary people as his subject, and ordinary life. He was a bit of a democract—a "Communard," as one of his friends remarked, referring to the left-wing revolutionaries of 1871; and he was fascinated by the way things distinct and different encountered each other: the city and the country, the farm and the factory, the bourgeois and the proletarian meeting at their edges in a sort of harmony of opposites."[9]

The border of the painting is, unusually, in inverted color, as if the world around them is also slowly inverting from the way of life they have known. Seen in this context, the boy who bathes on the other side of the river bank at Asnières appears to be calling out to them, as if to say, "We are the future. Come and join us".

Painting materials

Seurat painted the 'La Grande Jatte' in three distinct stages.[10] In the first stage, which was started in 1884, Seurat mixed his paints from several individual pigments and was still using dull earth pigments such as ochre or burnt sienna. In the second stage, during 1885 and 1886, Seurat dispensed with the earth pigments and also limited the number of individual pigments in his paints. This change in Seurat's palette was due to his application of the advanced color theories of his time. His intention was to paint small dots or strokes of pure color that would then mix on the retina of the beholder to achieve the desired color impression instead of the usual practice of mixing individual pigments.

Seurat's palette consisted of the usual pigments of his time[11][12] such as cobalt blue, emerald green and vermilion. Additionally, Seurat used then new pigment zinc yellow (zinc chromate), predominantly for yellow highlights in the sunlit grass in the middle of the painting but also in mixtures with orange and blue pigments. In the century and more since the painting's completion, the zinc yellow has darkened to brown—a color degeneration that was already showing in the painting in Seurat's lifetime.[13] The discoloration of the originally bright yellow zinc yellow (zinc chromate) to brownish color is due to the chemical reaction of the chromate ions to orange-colored dichromate ions.[14] In the third stage during 1888-89 Seurat added the colored borders to his composition.

The results of investigation into the discoloration of this painting have been ingeniously combined with further research into natural aging of paints to digitally rejuvenate the painting

In popular culture

The May 1976 issue of Playboy magazine featured Nancy Cameron—Playmate of the Month in January 1974—on its cover, superimposed on the painting in similar style. The often hidden bunny logo was disguised as one of the millions of dots.[21]

The painting and the life of its artist were the basis for the 1984 Broadway musical Sunday in the Park with George by Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine. Subsequently, the painting is sometimes referred to by the misnomer "Sunday in the Park".

The painting is prominently featured in the 1986 comedy film Ferris Bueller's Day Off. Such use is parodied, among others, in Looney Tunes: Back in Action and an episode of Family Guy.

In the Simpsons episode "Mom and Pop Art" (10x19), Barney Gumble offers to pay for a beer with a handmade reproduction of the painting.

At the Old Deaf School Park in Columbus, Ohio, sculptor James T. Mason re-created the painting in topiary form;[22] the installation was completed in 1989.

The painting was the inspiration for a commemorative poster printed for the 1993 Detroit Belle Isle Grand Prix, with racing cars and the Detroit skyline added.

In 2011, the cast of the US version of The Office re-created the painting for a poster to promote the show's seventh-season finale.[23]

The cover photo of the June 2014 edition of San Francisco magazine, "The Oakland Issue: Special Edition", features a scene on the shore of Lake Merritt that re-creates the poses of the figures in Seurat's painting.[24]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Sunday_Afternoon_on_the_Island_of_La_Grande_Jatte

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The scene in "Ferris Bueller's Day Off" where Cameron stares at the little girl in the painting is one of the most simple yet powerful scenes I've ever seen.

#i!!! have!!! feelings!!!#i have never related to a scene as much as i relate to this#ferris bueller's day off

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Art Institute of Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago

“Do you like museums? This one is famous for that scene in the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.”

“I love museums.”

“Which ones have you been to?”

“I’ve never been to a museum.”

I’ve walked past these lions many a time, and my mind always goes back to that movie scene where Cameron is staring intently into the little girls eyes in the painting, his own eyes welling up with tears.

I find that this p…

View On WordPress

0 notes