#eli de loyola

Photo

@turtle-brownie drew this lovely commission of sean and eli (my mc) singing and having a g(ay)reat time together ♡

commission her, friends! her art is amazing!!

#mc x sean#sean gayle#endless summer#playchoices#choices stories you play#pixelberry#male mc x sean#eli de loyola#elisean#i wanna write that really soon huhy#look at my fab gay ocs#mcsean karaoke au

147 notes

·

View notes

Photo

O Festival Universo Paralello comemora 20 anos em uma edição histórica a ser realizada entre os dias 27 de dezembro e 03 de janeiro de 2020. O local do evento fica na praia paradisíaca de Pratigi no litoral norte da Bahia, região da Costa do Dendê em meio a uma área preservada da Mata Atlântica. Um fantástico line-up com artistas vindos dos quatro cantos do mundo espalhados pelos sete palcos do festival. São eles: Tortuga Stage, 303 Stage, Chill Out, Aldeia Circulou, Palco Paralelo, UP Club e Main Floor. Trance, Psy Trance, Dark Trance, Progressive, House, Deephouse, Techno, EDM, Brazilian Bass, Lounge Music, Dubstep, Trap, Hip Hop, MPB, Rock Alternativo e muito mais. Performances, shows artísticos, palhaços, pirofagia, malabares, massagens terapêuticas, oficinas, reiki, chats, cinema, além de muitas surpresas estão sendo preparadas para o público. As mulheres tem seu papel de destaque no evento, sendo que na produção quase todas as áreas do festival são coordenadas por elas! E logicamente artistas, produtoras e DJs que trazem toda a energia e a vibe feminina. Destaque para Ekanta Jake, uma das DJs mais conhecidas da cena trance brasileira e coordenadora da (Pista 303); Eli Iwasa, Nana Torres, Fernanda Pistelli, Bruna Moura e Marian Flow da dupla Flow & Zeo (UP Club); a cantora baiana Luedji Luna, Savannah Lima, a rapper Lourena e DJ Cecilioui (Palco Paralello); Tati Seo, Marjo Lak, Deeh Fantinelli e Pri Loyola (Chill Out) são algumas representantes. 🔻🔻🔻 Confira o Line-up delas na íntegra e saiba mais acessando o nosso portal DJanemagBrasil.com.br (Link na bio ou nos destaques de 'Notícias' em nossos stories) . . . . . #UniversoParalello #Festival #Trance #PsyTrance #Lineup #DJanes #news #notícias #djanemagnews #djanemag #djanemagbr #djanemagbrasil #womandj #girlldj #mulherdj #grlpower (em Universo Paralello Festival) https://www.instagram.com/p/B5Y08P3l62X/?igshid=4xp76sirqic1

#universoparalello#festival#trance#psytrance#lineup#djanes#news#notícias#djanemagnews#djanemag#djanemagbr#djanemagbrasil#womandj#girlldj#mulherdj#grlpower

0 notes

Video

What to Do What to Do

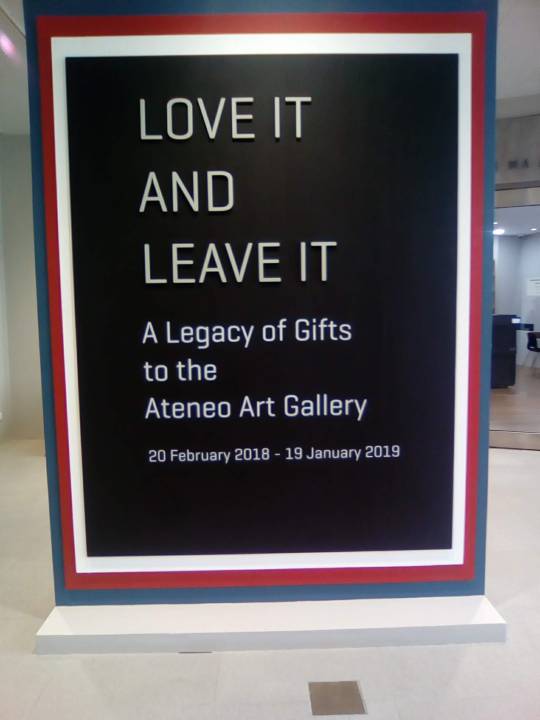

During the past days, I was always bothered about where should I go during my free time. By the time I entered Ateneo, it was almost time for the other interns to finish their OJT, hence I wasn’t able to get to know them. I was also too shy to eat with the staff during break times. Hence, I asked a friend from Ateneo to accompany me especially during lunch breaks. I was able to have a little tour of the Loyola Schools, thanks to him. I also learned how much food costs in the cafeteria haha. I was also able to visit the Areté after work hours; I highly recommend people to visit this place because it was so cool. It was like a bigger version of the Vargas Museum.

Here’s a donation box found inside the museum. You be the judge how rich people here are.

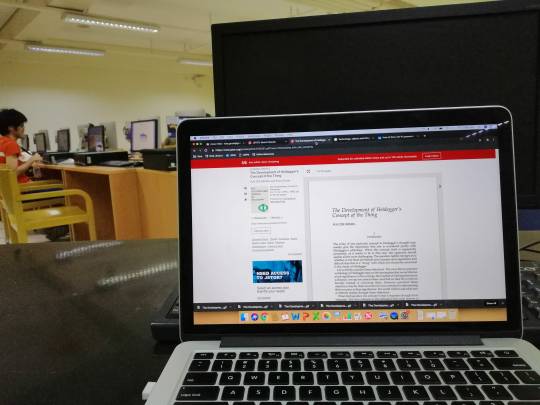

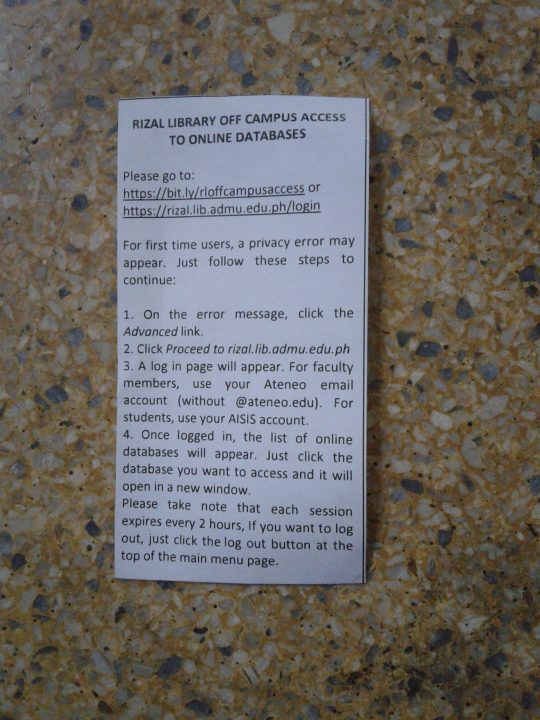

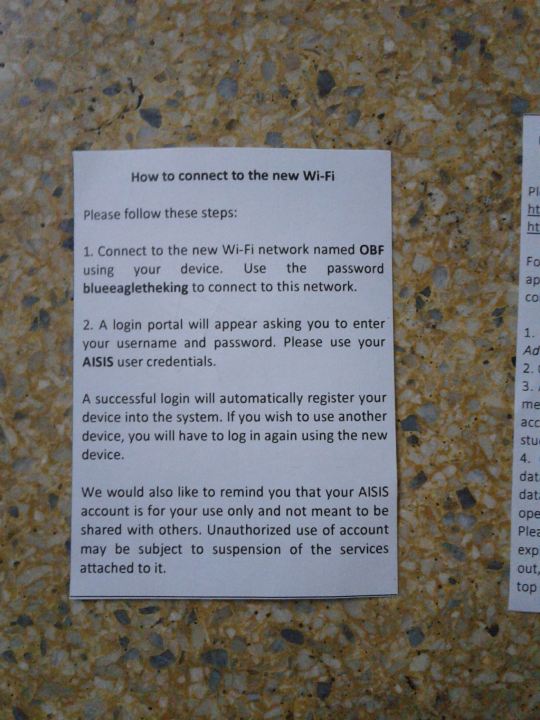

Aside from breaks, I was quite lost whenever the head librarian wasn’t available to entertain me or give me work. Good thing was they always refer me back to the Reference and Information Services Section (RISS). My schedule for Pardo de Tavera Collection and American Historical Collection Sections keeps postponing, that’s why I spent most of my time in the Reference Section. I think this would be my new favorite section because I get to see actual users. I was taught about what they do in the section, most of it was answering queries (which I just realized is the application for LIS 71). They are in charge of the doing the Services found in the website (http://rizal.library.ateneo.edu/). I was able to do the document delivery service (DDS): I was able to apply how to extensively search for articles that users were looking for on a library setting. It was there that I realized (what Sir Eli always says in LIS 71) that you should never give an I don’t know answer. If it cannot be found on the library’s online resources, you have to search for it online, or ask other partner schools (which I learned includes UP) if they have the material needed. I was awed that we are actually partners with other schools, hence we could help each other in sharing our resources. I learned that this section was considered as the face or representative of the whole Rizal Library: they handle the social media accounts of the library, they send and receive emails regarding events conducted by the library, they handle the library tours and orientation, and many more. They are like the Externals Committee of a student organization. Aside from doing the DDS, I was tasked to find for contact details of librarians from different institutions and email them regarding the upcoming event of the Rizal Library. I guess one of our skills as information specialists is being able to stalk people hehehe and of course finding the resource material needed.

During my stay at the RISS, I got to know about the Rizal Library Ambassadors (RLA). It’s an organization that consists of students who help in the work in the library, much like the student assistants in UP. Sometimes, I get to confuse which one is an RLA or an intern. Aside from students of the said org, I was also able to talk to users whenever they have a reference question: I was able to experience answering directional and ready reference questions (yey thanks LIS 71). In my stay there, I experienced handling a user who was a little spoiled for me. I told her how to use the OPAC but she told me to search for the material she needed myself. Oh well, every user is different and I just saw it in real life. Aside from things I learned in my subjects, there were other things that weren’t covered in classroom teaching. One of this is making an infographic hahaha. I have zero knowledge in doing photoshop. I was told to make infographics about these:

Since the RISS is in charge of the social media accounts, they take care of the info posted there. I guess that is why I needed to make an infographic that may be used in their facebook account.

For the past weeks, I got to know more about the campus too.

One major difference they have with the UP community is that they have fewer cats around.

They have a weird sense of humor too (I don’t know what the frog and arrangement of stones mean, but it they there since I arrived in the campus).

0 notes

Text

Mila Kunis Height Weight Measurements

New Post has been published on http://hollywoodages.com/mila-kunis-height-weight-measurements/

Mila Kunis Height Weight Measurements

Mila Kunis Biography

Milena Markovna “Mila” Kunis born August 14, 1983 is an American on-screen character. In 1991, at seven years old, she moved from the Ukrainian SSR to Los Angeles with her gang. In the wake of being selected in acting classes as an after-school action, she was soon found by a specialists. She showed up in a few TV arrangement and plugs, before securing her first noteworthy part preceding her fifteenth birthday, playing Jackie Burkhart on the TV arrangement That ’70s Show. Since 1999, she has voiced Meg Griffin on the energized arrangement Family Guy. Her breakout film part came in 2008, playing Rachel in the rom-com show Forgetting Sarah Marshall. Her different movies incorporate the neo-noir activity film Max Payne (2008), the post-prophetically calamitous activity film The Book of Eli (2010), the rom-com Friends with Benefits (2011), the satire Ted (2012), the dream Oz the Great and Powerful (2013) as the Wicked Witch of the West , and the film Black Swan (2010), in which her execution picked up her overall honors, including the Premio Marcello Mastroianni for Best Young Actor or Actress, and selections for the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress and Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Supporting Role.

Mila Kunis Personal Info.

Full Name:

Milena Markovna Kunis

Nick Name:

Mila Kunis, sweet lips, Goldfish

Family:

Mark Kunis – (Father)

Elvira Kunis – (Mother)

Michael Kunis – (Brother)

Wyatt Isabelle Kutcher (Daughter)

Education:

In Los Angeles, she went to Hubert Howe Bancroft Middle School. She utilized an on-set mentor for the majority of her secondary school years while shooting That ’70s Show. At the point when not on the set, she went to Fairfax High School, from which she graduated in 2001. She quickly went to UCLA and Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Date of Birth:

14 August, 1983

Birthplace:

Chernovtsy, Ukrainian SSR, USSR

Zodiac Sign:

Leo

Religion:

Jewish

Ethnicity:

White

Nationality:

krainian

Profession:

Voice Actress, Model, Actress

Measurements:

34-25-32 in or 86-63.5-81 cm

Bra Size:

32B

Height:

5′ 4″ (163 cm)

Weight:

115 lbs (52.2 kg)

Eye Color:

Hazel

Hair Color:

Brown – Dark

Dress Size:

04

Shoe Size:

7.5

Friends:

Natalie Portman, James Franco, Susan Curtis, Seth MacFarlane, Justin Timberlake, Alex Borstein, Seth Green, Emma Stone

Boyfriend/Dating History:

Macaulay Culkin (2002-2010) – When Mila Kunis was 18 she began an association with an American on-screen character Macaulay Culkin which kept going 8 years till 2010. They split in 2010 however made their declaration about in January 2011.

Ashton Kutcher (April 2012-Present) – American on-screen character Ashton Kutcher and his previous co-star, Mila Kunis began dating in April 2012 in the wake of meeting on the arrangement of “That ’70s Show.” They likewise played a couple on that appear and it served as an ignition for the off-screen dating also. On February 27, 2014, the pair got ready for marriage. In September 2014, Kunis and Kutcher respected their first tyke, little girl Wyatt Isabelle Kutcher. They wedded on July 4, 2015 in a mystery wedding.

Known For:

Jackie Burkhardt on “That 70s Show”, Meg Griffin on “Family Guy” and Lily in “Black Swan

Active Year:

1994 (present)

Favorite Food:

She likes everything

Favorite TV Programs:

8 Simple Rules (2002-2005)

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push();

Favorite Band:

Aerosmith

Favorite Movie:

Dirty Dancing (1987)

Favorite Perfume:

Kai Eau de Parfum

Favorite Color:

White

Official Twitter:

Twitter Account

Official Facebook:

FB Account

Mila Kunis Filmography:

Filmography

Film

Year Title 1995 Piranha 1996 Santa with Muscles 1997 Honey, We Shrunk Ourselves 1998 Krippendorf’s Tribe 1998 Milo 2001 Get Over It 2002 American Psycho 2 2004 Tony n’ Tina’s Wedding 2005 Stewie Griffin: The Untold Story 2007 After Sex 2007 Moving McAllister 2008 Boot Camp 2008 Forgetting Sarah Marshall 2008 Max Payne 2009 Extract 2010 The Book of Eli 2010 Date Night 2010 Black Swan 2011 Friends with Benefits 2012 Ted 2012 Tar 2013 Oz the Great and Powerful 2013 Blood Ties 2013 Third Person 2014 The Angriest Man in Brooklyn 2014 Annie 2015 Jupiter Ascending 2015 Hell and Back 2016 Bad Moms

Television

Year Title 1994 Days of Our Lives 1994

1995 Baywatch 1995 The John Larroquette Show 1995 Hudson Street 1996 Unhappily Ever After 1996–1997 Nick Freno: Licensed Teacher 1996���1997 7th Heaven 1997 Walker, Texas Ranger 1998 Gia 1998 Pensacola: Wings of Gold 1998–2006 That ’70s Show 1999–present Family Guy 2000–2002 Get Real 2002 MADtv 2004 Grounded for Life 2005–2011 Robot Chicken 2005 Punk’d 2009 The Cleveland Show 2010 The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson 2011 Sesame Street 2011 Night of the Hurricane 2011 Good Vibes 2014 Two and a Half Men

Search Terms:

Mila Kunis Ashton Kutcher. Mila Kunis Age. Mila Kunis Baby Name. Mila Kunis Birthday. Mila Kunis Boyfriend. Mila Kunis Bio. Mila Kunis Brother. Mila Kunis College. Mila Kunis Daughter. Mila Kunis Dress. Mila Kunis Dad. Mila Kunis Dark Hair. Mila Kunis Eyes. Mila Kunis Education. Mila Kunis Family. Mila Kunis Facebook. Mila Kunis Filmography. Mila Kunis Films. Mila Kunis Gallery. Mila Kunis Husband. Mila Kunis Hair. Mila Kunis Hair Color. Mila Kunis Hairstyles. Mila Kunis Movies. Mila Kunis Married. Mila Kunis Movies And Tv Shows. Mila Kunis Marriage. Mila Kunis Movies List. Mila Kunis Mom. Mila Kunis Mother. Mila Kunis Nationality. Mila Kunis New Movie. Mila Kunis Natural Hair. Mila Kunis Parents. Mila Kunis Photo. Mila Kunis Profile. Mila Kunis Real Name. Mila Kunis Relationship. Mila Kunis Style. Mila Kunis Shows. Mila Kunis Twitter. Mila Kunis Upcoming Movies. Mila Kunis Wedding. Mila Kunis Wiki. Mila Kunis Wallpaper. Mila Kunis Zodiac.

#bio#bra cup size#bust#dress#eye color#facebook#father name#filmography#google +#hair color#height#hips size#horoscope#mila kunis#mother name#movies#nick name#profession#profile#shoe size#tv#twitter#waist size

0 notes

Text

YENİÇAĞ İSPANYA’SINDA BİR SKANDAL OLARAK SERSERİLİK ‘CULTURA PICARO’

Picaro, kelimesi gezgin başıboş serseri hatta düzenbaz manasına gelen İspanyolca bir kelimedir. Pikaresk roman ise Ortaçağ’da moda olan edebiyattaki kır konulu eserlere ve şövalye romanslarına tepki olarak doğmuştu ve yıllar içinde anonim olsun olmasın etraf gezgin serseri romanlarıyla dolup taştı.

Bunların ilki-engizisyon korkusundan yazar isimi olmaksızın yayınlanan Tormesli Lazarillo en ünlüsü ise Don Kişot dur.

Cervantes 1547 de doğmuş yedi çocuklu bir ailenin oğluydu.

Şiir ve romana genç yaşta ilgi duymuş ilk şiiri gittiği okulun gazetesinde basılmıştı. Babası bir cerrah ve hatta düşmüş bir soyluydu. Babasının maddi durumu nedeniyle ilk seyahat tecrübelerini babasının alacaklılarından kaçarken şehir şehir dolaşırken yaptı. Bir süre tiyatro oyunlarıyla geçimini sağladı. 1552 yılında borçları yüzünden hapse girdi. Ailesiyle yeni başkent yapılan Madrid’e taşınan Cervantes burada okula başladı. 1569 yılına gelindiğinde ise Cervantes ’ in tüm hayatını değiştiren olay meydana geldi. Rivayete göre bir kadın meselesinden arkadaşıyla yaptığı düelloda onu yaraladı. Cezasının sağ eli kesme ve on yıl sürgün olduğunu öğrenince İtalya’ya kaçtı. O zaman Madrid’de oturan birinin Roma’ya gitmesi, günümüzde Ortadoğulu birinin New York’a göç etmesiyle aynıydı. Madrid’in sığ ortamından Hristiyanlığın ve entelektüel dünyanın merkezi konumundaki Roma onun hayat görüşünde önemli değişikliklere yol açtı.

1570’te Papa V. Pius Osmanlılara karşı birlik çağrısında bulunur. Çağrıya yalnızca İspanya ve Venedik karşılık verir. Cervantes Roma’daki İspanyol birliğine katılır. Osmanlı donanmasıyla İnebahtı Deniz Savaşı’na katılan Marquesa adlı kadırgada bulunan Cervantes; iki kez göğsünden yaralanır, bir top güllesiyle sol eli sakat kalır.

kalkan bir gemiyle ülkesine dönmek için hareket eder. Talihsizlik bu ya gemisi Türk korsanların eline geçer ve Cezayir’e götürülür ve köle olarak Hasan Paşanın emrine girer. Hasan Paşa onunla çok iyi geçinir hatta dört kere kaçma girişiminde bulunmasına rağmen onu cezalandırmaz. Esaret hayatı beş yıl sürer. Bu İspanyol kaynaklarının prezante ettiği bir bilgidir. Beş yılda bir sorun yoktur ama birkaç yıl önce Osmanlı arşivlerinden çıkan bir belge Cervantes’i batının hayal dünyalarına yani bin bir gece masallarına gönderir. Kaptan ı derya Kılıç Ali Paşanın kendi adına Mimar Sinan’a yaptırdığı cami inşaatında tutulan çalışan listesindeki ameleler bölümünde tanıdık bir isim bize göz kırpar; Miguel Cervantes Saavedra... Kendisi de bir İtalyan devşirmesi olan Kılıç Ali Paşa’yla İtalyanca hoşbeş ettikleri ve Paşanın çalışmadan memnun kalıp bütün ameleleri azat ettiği de bilgiler arasındadır.

İspanyol kaynaklarına göre Cezayir’de fidye ile Türk kaynaklarına göreyse serbest bırakılarak tekrar İspanya’ya dönen kahramanımız saraydan aldığı görevlerle yaşamasını sürdürse de onu tatmin etmedi ve tekrar edebiyatla ilgilenmeye başladı. Yazdığı oyunların tamamının sergilenmesine rağmen annesi karısı kız kardeşleri ve gayrimeşru kızına bakmak onu maddi olarak çökertti. Sevilla’da gidip iş aradı. Ambar memurluğu yaparken bir yandan oyun yazarlığını sürdürdü. Fakat 1592’de yolsuzluktan tutuklandı ama birkaç gün sonra serbest bırakıldı. 1596’da katıldığı bir şiir yarışmasında yine birincilik ödülünü kazandı. Aynı yıl yine bir yolsuzluk suçlamasıyla tutuklandı ve memurluk hayatı bitti. Sıra geçirdiği onca çileli ve maceralı hayatının balını süzmeye gelmişti. 1605’de Don Kişot’un ilk cildi yayınlandı. Kitap Cervantes’e ünden başka bir şey getirmedi ve yine yayıncısından borç aldı. Aynı yıl artık bir adete dönüşen vukuatlarına bir yenisi yaşanıyordu. Evinin önünde karıştığı bir kavga sonuncunda bu defa ailecek hapishaneye atıldılar.

1608’e gelindiğinde Kont Lope’nin yardımlarını gördü. 1612’de prestijli Selvaje akademisi üyesi oldu. Cervantes ünlü “Örnek alınacak hikayeler” kitabını konta ithaf etti ve sonunda maddi durumu biraz düzeldi. Kitap Cervantes’e İspanyol edebiyatının ilk öykü yazarı unvanını getirdi.

Americo Castro, “Don Kişot, batı tarihinin dar ufkunda değerlendirildiğinde tam manasıyla anlaşılamaz” der. Kitabın 2. cildinde Don Kişot’un sözleri Castro’nun ‘doğu’ ve ‘batı’ imgelemesinin hakikatini anlatır bize “Ben ölerek yaşamak için doğdum, sense yiyerek ölmek için”. Roman, eski zamanlardaki şövalye romanlarının ti’ ye alınması ya da kısa öykülerden oluşan eklektik bir yapısı olması aslında bir alegoridir. Uzun uzun meseleye girmeden kısaca şunları söyleyelim; Don da Sancho da Cervantes’in ta kendisidir. Cervantes’in Don Kişot karakterinde neşvünema bulan hayalleri çılgınlıkları ihtiraslarının karşısında duran komik ve cahil Sancho Panza’da vücuda gelmiş karakterde Cervantes adeta kendine, basit ihtirassız sıradan bir hayatı telkin etmektedir. Sancho, ihtirasları pesinde koşan Cervantes’in gençliğindeki ham nefsine benzer. Sancho Don’un entelektüel

hayalperest kişiliğinin karşısında duran acı gerçekler gibidir. Sancho cahil olduğu için uzun cümleler kuramaz ve bir cümleye dünyaları sığdırırken Don, sahip olduğu zengin ve şiirsel vokabüler ve ihtiraslı retoriğe rağmen sanki kendi etrafında dönüp durur gibidir. Yazar kültürlü insanların adeta kendi yarattıkları labirentlerde kaybolduklarını ima eder ve hayallerinin, onu perişan ve adeta deli ettiğini göstererek açıkça kendiyle dalga geçer. Don Kişot hudutsuz yani müteal ontolojik yapısıyla adeta İslam tefekküründeki vücudu, Sancho Panza ise onu frenlemeye çalışan sınırlı aklı temsiliyle bir sınır devriyesi gibi Don’un karşısında duran şuhud’u remzeder ..

"Ben; debdebe içerisinde yaşayan, dış görünüşüme son derece dikkat eden, kadınlarla ilişkisi iyi olan, gururuma dokunan hareketlere karşı keskin ve korkusuz bir şekilde cevap veren, kendimin ve başkalarının hayatını küçümseyen biriydim"

Yakın arkadaşı Luis González

Yaklaşık on yıl eğlence dans balo ve silahlı düello ile geçen bu görevi sürdürdü.

Ali Murat Yel -Divan dergisi

“Özellikle oyunlarda, düellolarda ve kadınlarla olan ilişkilerinde onlara fazla yüz vermiş kendini kaptırmıştır”

Sekreteri Polanco

“Ignattius inanca her ne kadar önem verse de inancını yaşama ve kendini günahlardan koruma gayreti içinde değildi. O özellikle kumar kadınlarla haşır neşir olma ve silah kullanma konularında dikkatli davranmıyordu”

Arkadaşla

Yukarıdaki yazılarda bahsi gecen kişinin Hristiyan dünyasını siyaseten Avrupa’yı bir kaç yüzyıl domine eden Avrupa ve dünyanın çeşitli yerlerinde karışıklıklara yol açan Cizvit tarikatının kurucusu olduğunu söylersek hayli şaşırtıcı olurdu herhalde. En yukarıda Zevaco’nun romanında kişileştirilen Loyola karakteri kurgunun bir parçası olmasına rağmen Cizvit tarikatının durumu pek de abartılmış sayılmaz.

Tam adıyla Ignatius Lopez de Loyola 1491’de bask bölgesinde zengin bir ailenin on üçüncü çocuğu olarak dünyaya geldi. On beş yaşında Kral Ferdinand in sarayına yetiştirilmek üzere verildi. Bir süre sonra şövalyeliğe kadar yükseldi.

Loyola nin gençlik hayatı ise çok ciddi bir Hristiyan tarikatının kuran biri ile gece ile gündüz kadar farklıdır.

Kesin olmamakla birlikte Loyola bir askeri eğitimden geçmişti ve Cizvitler in ünlü disiplin ve hiyerarşik düzeni de askeri bir yapıyı andırır.

17 Mayıs 1521 Loyola’yı tanımamızı sağlayan olaylar zincirinin başladığı tarihtir. Fransa ile Pamplona’da yapılan savaşa katılan Loyola bacağından ağır şekilde yaralandı. Bir evde devam eden tedavisi ve nekahet dönemi boyunca okumak için en sevdiği kitapları istedi yani şövalye romanlarını... Ne yazık ki kaldığı evde azizlerin hayatlarını anlatan kitaplardan başkası yoktu. O da sıkıntıdan kitapları okudu.

Manevi dönüşümü de bu olayla başladı. Azizlerin hikayelerinden etkilenen Loyola azizlerin kendi askeri maceraları düelloları ve olmak istediği her şeyden daha önemli işler başardığını düşündü.

Okuduğu kitaplar arasında özellikle Dominik rahibi Voraginee ye ait Golden Legend önemlidir. Kitapta azizlerden Tanrının Şovalyeleri olarak bahseder. Loyola’yı öncelikle bu tabir etkilemiş olmalıdır çünkü Cizvitlerin günümüzde de anıldıkları isimlerden biri budur. Loyola ’ nın kendi kendine aziz Francis şöyle yaptı aziz Dominik böyle yaptı ben de yapmalıyım diye söylendiği bilinmektedir.

İyileştikten sonra uzun süre Manresa’da kalmış Cizvitlerin kılavuz kitabı Ekzersizler kitabını burada yazmaya başlamıştır. 1523 yılında aksiyoner kişiliği tekrar devreye girmiş ve Kudüs’ü Hristiyanlaştırmak üzere Tanrının kendini görevlendirdiği söyleyip Kudüs’e gitti. Bir süre kaldıktan sonra Fransisken rahiplerin Kudüs ün kendisi için tehlikeli olacağını telkin etmeleri üzerine şehri terk etmiştir. Bazı söylenenlere göreyse ılımlı hareketleriyle tanınan Fransisken cemiyeti Loyola’nın faaliyetlerinin Müslümanlarla aralarını açabileceğini düşünüp bir takım bahanelerle onu uzaklaştırdıklarıdır. Ispanyadan Romaya gelen Loyola ’nin Kudüs e gitmesi de hayli zor olmuştu Türklerin kontrolünde olan bu şehre gitmemesi tavsiye ediliyordu. Rodos adasının da düşmesi, Roma’daki yakalanan Türk casuslar fikrini bir süre daha ertelenmesini sağladı.

Loyola Kudüs’e dönünce eğitimin her şey olduğunu anladı ve tüm çabasını kişisel eğitimine yöneltti. Barcelonada latince Paris giderek fransızca öğrendi. Alcala şehrinde heretiklikle suçlayarak mahkemeye çıkarıldı suçsuz bulununca şehri terkederek Salamanca’ya gitti. Bu defa arkadaşlarıyla tekrar tutuklandı. Mahkeme sonunda salıverilse de dini faaliyetleri yasaklandı. O da Ispanya’yi terk etti ve Paris’in yolunu tuttu. Bu şehirde Montaigu kolejinde felsefe Aristo fiziği üzerine çalıştı. Loyola Paris’te binlerce sayfalık yazılar yazmış bir kaç arkadaşıyla Hz İsa’nın hizmetkârları isimli bir birlik kurmuştur. Kısa bir süre ingiltere’ye giden Loyola burada tarikatı için tıpkı Fransisken rahipleri gibi dilenerek para topladı. Sonra tekrar Paris Venedik ve Bologna’ya giderek eğitimini sürdürdü. 1534 de arkadaşlarıyla tekrar Kudüs’e gitmek istemişler ama bunun olanaksızlığını anlayınca Papaya bağlılık yemini ettiler ve 1540 yılında Papalık Cizvit tarikatını resmen tanıdı. Cizvitlerin Loyola ’ nın sağlığında sayıları bine ulaştı Loyola, Avrupa’nin başlıca yerleri dışında Hindistan Etiyopya, Kongo ya da cizvit rahiplerin göndermişti.

Cizvitlerin Dominiken ve Fransiskenler den ayıran çok önemli farkları vardır. Cizvitler keşiş kıyafeti giymezler manastıra kapanmazlar ibadet ve tefekkür gibi konularda da iki cemiyetten ayrılırlar. Dominikenler merkez olarak incili Cizvitler ve Frasiskenler İsa merkezli bir itikada sahiptirler Cizvitler Papaya itaati esas almasıyla da diğerlerinden ayrılır. Loyola’nin geçmişinden dolayı askeri disiplin esastır ve “Corps delite” yani ‘ölü gibi itaat’ prensibine bağlıdırlar.

Ama en önemli özellikleri esnek bir düşünce yapısına sahip diyalogcu anlayışlarıdır. İkincisi ise bize Fetö’den tanıdık! gelebilecek özellikleridir. Cizvitler dünyanın dört bir yerinde kendi okullarını açmışlardır. Kendilerine görev verildiğinde mesafe tanımaksızın tıpkı bir asker gibi hedeflerine yönelirler. Çin in Hristiyanlık la tanışması dahi Cizvitlerin sayesinde olmuş Papalık in takdirini kazanmışlardır. Alfred Hitchcock Bill Clinton, Fidel Castro, Conan Doyle da Cizvit okullarından mezun olmuşlardır.

18.yuzyila gelindiğinde tıpkı Tapınak Şövalyeleri gibi her tarafa kök salmış hem kilise hem diğer cemiyetler tarafından bir tehlike olarak görülmeye başlamışlardı. Hatta Protestanlıkla dâhi suçladılar gerçektende belki görüntüde de

olsa Cizvitler ruhban anlayışının olmadığı bir Hristiyanlık vadeder görüntü veriyordu.

DEĞERLENDİRME

Böylesine iki maceraperestin kısaca pikaresk hayat öykülerini okuduk. Burnundan kıl aldırmayan çapkın dış görünüşüne önem veren yani kısaca maddeci gururu yani şan ve şöhret için yaşayan bunlar için kılıcını çekmekten kaçınmayan bir insan nasıl olup ta itikadı için dilencilik yapmaya başlayabilir. Nasıl olur da fakirlik ve iffet yemini ederek dünyaya oruçlu bir hayata geçiş yapar. Bunun altında biz de materyalist bir neden aramak değil, yani ‘nasıl’ın değil ‘niye’nin sebebini aramak gibi bir niyetimiz var. Hattı zatında İslam inancında da sebeplerin majör önemleri yoktur ve bunlar sadece olacak şeyin Hakk’ın bizim anlayabileceğimiz şekilde “şeyleri” senaryolaştırmak istemesinden kaynaklanmaktadır. Kısaca insanoğlunun bir senaryoya ihtiyacı vardır. Her şeyin bir senaryosu vardır ve bu felsefe sanat ontoloji ilahiyat ve edebiyat için gereklidir. Sebepler ise dinlediğimiz müziğin anlamadığımız notaları gibidir.

Loyola gibi narsist kişilik bozukluğu olan insanlarında geçirdiği dönüşümü anlatacak bir hikâye olmalıdır. Her zaman kendinden kahramanlıklarından bahsedilmesini isteyen Loyola nasıl olup da bir iman şövalyesine dönüşmüştür? Cevabı yine kendi sözlerinde azizlerden bahsederken görüyoruz.

“Burada kahramanlık anlatılır ve bu kahramanlık, benim göstermiş olduğum kahramanlıktan daha üstündür. Acaba ben, bu tür eylemleri yapabilir miyim?..

Loyola için ilerleyici güç yine adından söz ettirmek olmuştur.

Cizvitlerin kilise tarafından da başlangıçta desteklenmelerinin ana sebeplerinden biri Protestanlığa karşı girişilen karşı reform hareketinde girişken politikalarıyla etkin bir rol oynamalarıdır.

Ama 18. Yüz yıla girildiğinde hem kilise hem de kilise dışı minvaller tarafından ağır şekilde eleştiriye uğramaları enteresandır. Sonunda 1773 Kilise tarikatın kapatılmasına karar verdi. Kilise böyle bir kararı neden verdi? Zevaco’nun romanında aktarılan senaryo, bu gibi cemiyetlerin herkes tarafından bilinen aksiyonlarıydı. Buna dışarıdan ‘derin kilise’ deyip geçiştirilir zaten daha fazlasını bilmek mümkün değil. Ayni tapınak şövalyelerinin başına gelenler gibi yani tapınağın kiliseden güçlenmesi ya da ona şantaj yapmaları söylenceleri gibi ama kilise tapınağı bir gece de bitirmişti. Acaba kilise ya da bir takım şeylerin arkasında bu derin amcalar mı var?

Kilise bu gibi cemiyetleri ustaca manipüle edip onların kendilerini yönettiği izlenimini verip sonra tasfiye mi ediyor? Nitekim Papa Pius misyonerlik ve sosyal ilişkiler uzmanı olmaları gerekçesiyle Cizvit tarikatının tekrar açılmasına karar vermiştir. Görüldüğü gibi kombinasyonların sonu yok. Cizvitlerin eğitime verdiği önem dünyanın dört bir yanına açtığı okullar bu yapılanmayı hatırlatıyor.

Cervantes Loyola kadar şanslı değildi yani soylu bir aileye mensup değildi yaşamaya çalıştı şehirden şehire kaçıp sonra ülkeden firar etti dolandırıcılık suçlarından düellodan tutuklandı ya da kaçtı kahramanlığını göstermek için savaşa katildi eli sakatlandı beş yıl esir hayati yaşadı ülkesine dönünce hayatının sonlarına kadar sıkıntılar ve mahkemeler bitmedi. Cervantes’in kavgaları af olunduktan sonra tekrar Roma’ya donen başka bir iflah olmaz kavgacı Caravaggio’nun kutlama için gittiği meyhanede enginar yüzünden garsonla ettiği simültane kavgaları gibi değil gururundan başka bir şeyi olmayan fakir bir insanın mücadelesiydi bence. Loloya’nın

ise gençliğindeki kibri ve gururlu karakterinden kısaca şımarıklığındandı. Sürekli bir kendini gösterme eğilimi olduğu açıktır.

İspanyol edebiyatında şövalye romansları nasıl ki gözden düşüp yerini pikaresk edebiyata bıraktıysa Loyola da - ki kendisi de bir şövalyedir- soyluların hayatını bırakıp yollara düşmüş pikaresk hayata dönmüştür. Don Kişot ise büyük İspanya İmparatorluğunun çöküşünü gösteren çıldırmış bir şövalyede temsil olunur. İki karakterde biri gönüllü diğeri suda sürüklenen çöp misali bir yasam sürüp arkalarında yazılacak sayfalarca anı bıraktılar...

SONUÇ

Güçlenen organizasyonlar bir süre sonra psikosomatik kişilik bozukluğu gösteren bireylere benzemektedirler...

Şahıs ya da tüzel kişilikler kendilerini layüsel ve layemut ilan etmekte ve öyle zannetmektedirler...

Bu, liderlerinin deliliğinden de kendilerini takım kültürüne ait hisseden bireylerinden de kaynaklanabilir...

Büyük eserler seyri sülüğünü tamamlamış bireyler tarafından verilir...

Çok gezen daha iyi bilir...

İnsan ilişkileri en önemli şeydir...

Yanınızdakinin kim olduğunu bilemeyebilirsiniz...

Cervantes gibi dâhilere belki de günümüzde şizofren teşhisi konulacaktı ve belki de bu onların anlayamadığımız yeteneklerinin açıklamasıdır...

Mafya da dâhil büyük organize yapılanmaların, güçlü çekirdek aile yapısı olan, emperyal kültür kodlarına sahip milletlerden çıktığını görüyoruz...

“İnsanlar da kuyulara benzer, içlerinde boğulabilirsiniz”

Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar

“İnsanları uyandırmak gerek. Algılama biçimlerini altüst etmek, pek de güvenilir olmayan tuhaf bir dünyada yasadıklarını, sandıkları gibi bir dünyada bulunmadıklarını anlamalarını sağlamak gerek”

Don Kişot...

Emre Demirok

10.Şubat. 2017

Kaynaklar

Prof. Ali İsra Güngör, Cizvitler, ilgi Kültür yay.

Vladimir Nobakov, Don Kişot Dersleri, iletişim yay.

Ana Britannica Ansiklopedisi.

Ali Murat Yel, Divan dergisinde çıkan makalesi

Michel Zevaco, Serseriler yatağı, İnkılap yay.

Wikipedia

0 notes

Text

8-1 | Table of Contents | DOI 10.17742/IMAGE.GDR.8-1.8 | WeinrebPDF Coming Soon!

[column size=one_half position=first ]Abstract | This essay uses the topic of taste, specifically taste for food, as a way of unpacking the history of the GDR and East-West relations during the late Cold War. It explores the question of East German tastes from two angles: West German fantasies about the inadequacies of the GDR’s food system, and East German nutritionists’ unsuccessful struggles to regulate popular tastes. In particular, it focuses on the moment when popular taste was seen as a serious problem by the GDR state—during the rise of the obesity epidemic in the 1970s and 1980s. [/column]

[column size=one_half position=last ]Résumé | Cet essai utilise le thème du goût, spécifiquement le goût pour la nourriture, comme un moyen de dévoiler l’histoire de la RDA et les relations Est-Ouest pendant la fin de la guerre froide. Il examine la question des goûts de l’Allemagne de l’Est sous deux angles: Les fantaisies des ouest-allemands sur les insuffisances du système alimentaire de la RDA, et les luttes infructueuses des spécialistes de la nutrition est-allemands pour réglementer les goûts populaires. L’essai se concentre en particulière sur le moment où le goût populaire a été considéré comme un problème grave par l’état de la RDA—pendant l’augmentation de l’épidémie d’obésité dans les années 1970 et 1980.[/column]

Alice Weinreb | Loyola University Chicago

It Tastes like the East…:

The Problem of Taste in the GDR

In the autumn of 1999, just a few months after I had moved to Berlin for a post-college fellowship, I attended a party hosted by a good friend. Like most of my friends at that time, she was East German, a fact of which I was barely aware. This particular party proved unexpectedly memorable, however, as it was the stage for my first experience of the infamous Mauer im Kopf, the “Wall in the head” that was still a subject of much debate a decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall’s. The hostess had provided abundant snacks for our enjoyment, including, to my delight, one of my favorite sweets: Knusperflocken, small candies made of crunchy grain and milk chocolate. I was enthusiastically reaching for a handful when a guest warned me away: “I can’t believe it—don’t eat those,” he said. “Those are so Ossi [East German].” “What do you mean,” I asked innocently, “I think they’re delicious.” “No, they are not,” he insisted, “they only have two ingredients!” This both simple and nonsensical answer revealed that this Wessi defined East German food by what he perceived as inadequacy and lack—not poor flavor per se, but the abstract problem of having “only” two ingredients (chocolate and grain). His bizarre explanation bemused me; it only began to make sense as part of a larger discourse that pervaded recently reunified Germany. It also was my first exposure to the pervasiveness of food-based fantasies on the part of both East and West Germans with regard to one another in the wake of reunification.

Perhaps the most famous example of this sort of West German fantasy of East German “bad taste” is the infamous satirical magazine Titanic’s cover image from November 1989: the smiling “Zonen-Gabi,” or “Gabi from the [Eastern] zone,” holds an enormous peeled cucumber, under the headline, “My first banana” (See Cover Image/ Fig. 1). The Titanic picture was only the most famous in a veritable flood of cartoons and images memorializing the fall of the Wall—an overwhelming number of which focused on bananas (Seeßlen). These jokes almost always described a profound East German desire for bananas, one that was so strong it bordered on the pathological. For example, East Germans were depicted as monkeys or as ravenous hordes consuming overnight the entire supply of bananas in the FRG (Federal Republic of Germany or West Germany). These jokes often revolved around the idea that East Germans’ tastes were so underdeveloped that they could not actually identify a banana when they ate it—or did not, as the case may be. Most frequent was the premise of the Titanic image: an East German ate a pickle, cucumber, sausage, or other deeply familiar food, but in their ignorance they “tasted” a banana. In other words, post-reunification discourse on the GDR normalized assumptions not only about how much East Germans ate (a lot) and what they ate (drab, non-delicious foods), but also about their inability to identify specific flavors. Most of these jokes could be summed up with the premise that the GDR was a land inhabited by people who were universally afflicted with “bad taste.”

Theories of taste have been a crucial part of discussions of class, difference, and identity at least since Pierre Bourdieu’s influential work Distinction, in which the sociologist noted that “tastes in food also depend on the idea each class has of the body and of the effects of food on the body, that is, on its strength, health and beauty” (190). However, taste is not simply a component of the expression of individual and collective identity. People’s tastes in food have long been a central concern of modern states. Economists and nutritionists have struggled to determine, explain, and modify individual tastes in food since the emergence of the industrial economy; the rise of industrialization meant that economic health depended upon eating habits. Labour productivity was seen as directly related to popular diets, and food production and consumption became increasingly important components of the national economy. This recognition of the economic and social significance of individual dietary preferences has inspired countless projects to improve how and what populations eat. However, nutritionists’ consistent failures to modify what they consider unhealthy popular eating habits has only confirmed anthropologist Jack Goody’s observation that foodways often seem to be “the most conservative aspects of culture” (150). Indeed, since the emergence of the modern nutritional sciences, nutritionists have consistently complained about the near-impossibility of changing popular tastes (“Psychologische Grundlagen des Ernährungsverhaltens”). As a West German nutritionist explained grimly in 1967, “it is the task of nutritionists to work against false dietary habits, and this obligation makes nutritionists unpopular. Nowhere is the human spirit less reasonable and more stubborn than when it is defending traditional, and false eating habits” (Holtmeier 312). Thus taste remains individual and almost impossible for external forces to regulate at the same time peoples’ tastes in food matter profoundly to modern states because they determine what and how much individuals eat.

Scholarship on the GDR has only recently begun to address issues of food production and consumption as key components of everyday life (Ciesla and Poutrus). This literature has explored the struggles to purchase foodstuffs given the vagaries of a socialist economy. Poor quality products, irregular and inadequate supplies, and inequitable and unpredictable distribution shaped consumer culture generally, but also of course how and what people ate. Historians have been less aware, however, of the ways in which the GDR’s distinctive food culture incorporated citizens’, especially East German women’s, struggles to purchase foodstuffs. Moreover, they have ignored the function of an elaborate network of collective-eating establishments in workplace canteens and school lunch programs, as well as a variety of private strategies for food acquisition, including a reliance on private gardens and barter and trade as methods of compensating for inadequate state-provided supplies. In general, the expanding literature on consumption practices in the GDR has rarely explored the issue of taste. While scholars such as Paul Betts, Judd Stitziel, and Eli Rubin have addressed the relationship between taste and East German identity vis-à-vis, respectively, furniture, fashion, and plastics, food has been marginal to these discussions. Nonetheless expressions of taste as a strategy of social ordering and hierarchy are inseparable from food itself. While we usually assume that good taste (or flavor) determines the foods that we eat, we simultaneously believe that other people’s “wrong” food choices are made because of their underdeveloped or inadequate tastes. In fact, the relationship between the actual flavor of specific foods and their symbolic association with “good taste” or “bad taste” is fluid, often contradictory, and heavily influenced by larger external political and social categories.

This essay thinks about the category of taste as a way of exploring both the history and the legacy of the GDR by focusing upon two distinct discourses that constructed East German popular food tastes as flawed or bad. The East German medical establishment reached a consensus that its population was too fat as a result of its inappropriate desire to consume both too much food and the wrong sort of food. This conforms to the anti-obesity movements of the 1970s and 1980s, the decades that witnessed the emergence of a so-called obesity epidemic in both East and West Germany. Obesity posed a particular problem to the socialist state because its very existence suggested that popular, ordinary taste was flawed, and that the sorts of foodways generally internalized as central to the state’s identity caused serious health problems. This disturbing idea that East German citizens did not, in fact, like the “correct” foods suggested that some core values of socialism needed to be redefined. The obesity epidemic thus became a source of tension between nutritionists, who believed that excessive levels of fatness revealed poor eating habits, and a larger political, economic, and cultural discourse that associated socialism with cheap, abundant, and tasty foods. I compare this tension surrounding East German obesity with West German descriptions of East Germans as both impoverished and overweight, relying upon poor-tasting and undesirable foodstuffs. Here, East Germans’ poor taste was imagined as being the direct and inevitable result of the socialist economic system; West Germans imagined the East German population as icons of “bad taste” because they were forced to live within the inadequate consumer landscape of state socialism. Although these discourses served different purposes and emerged out of different contexts, they shared a common perception of the flawed nature of East German bodies and appetites.

Western Fantasies of Eastern Food

The conceptualization of East Germans as possessing singularly unsophisticated palates and inferior gustatory culture had a long tradition in the FRG. During the decades of Cold War division, mainstream West German discourse invoked two distinct and seemingly opposed images of the East German body: the starving victim of communism and the overweight and unsophisticated socialist citizen. Neither of these clichés was specific to the FRG. At least since the Russian Revolution, Western anti-communists associated communism with food shortages and even famine (Veit). During the Cold War, the emergence of private consumption as a primary sphere of global competition generally associated the Eastern Bloc with an underdeveloped, inadequate, and unattractive consumer market. In the case of divided Germany, however, these general patterns proved ubiquitous and long-lasting. Here popular discourse invoked these pathologized bodies to represent a distorted consumer culture and the profound inadequacies of the GDR’s political and economic system more generally.[i] In addition, these stereotypes of East German bodies assumed that what and how East Germans ate was central to their overall lived experiences.

In the newly developing rhetoric of the Cold War, the sameness and anti-individualism that was thought to be a hallmark of communism became associated with poor quality and inadequate supply. Convinced, in the words of the West German agricultural expert Frieda Wunderlich, that the goal of the Soviets had always been “above all the ruin of East German agriculture,” anti-communists believed that a socialist government naturally resulted in malnourishment and hunger (50). The weekly news magazine Der Spiegel regularly reported throughout the 1950s and 1960s that “hunger, the vulture that circles over the socialist reconstruction, is hovering over the German Soviet Zone” (“Schweinemord”), as the German Democratic Republic was often termed in Western media. Until the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, Grüne Woche (Green Week), the major West German agricultural convention held annually in West Berlin, offered free food samples to East German visitors who were assumed to suffer from severe shortages. Indeed, beginning in the late 1950s, the West Berlin government began stockpiling vast amounts of groceries in city storehouses, as advisors predicted a food crisis as a result of an anticipated unification. Decades before Gabi was depicted devouring her “banana,” West German economists imagined hordes of half-starved East Germans gobbling up their supplies of sugar, butter, and meat (Betr: Arbeitsgruppe “Lebensmittelindustrie”). Throughout the years of division and regardless of the actual nutritional status of the population, West German depictions of life in the GDR relied upon tropes of hunger and deprivation that had been established during earlier experiences of poverty and shortages: poorly stocked stores and empty shelves, meager obligatory canteen meals, and never-satisfied cravings. For the FRG, the GDR became a key symbol of and shorthand for German hunger.

This vision of the GDR as a place of hunger and underdevelopment was encouraged by the steady shipments of West Packages (Westpakete) sent eastward across the border. They contained everything from bonbons to soaps, exotic fruits to stockings, noodles to imported chocolates. West Germans began sending packages by the thousands to family, friends, and strangers in the GDR. As a 1954 ad in the popular West German magazine Prima explained to its readers:

[F]ood packages seem to be a permanent aspect of our age. Before the currency reform, many lives depended on them. That’s how it was with us. Then came the great [currency] reform, and suddenly we were no longer dependent on the food packages. We were not. But on the other side of the oft-cited curtain not much has changed, and so we now send packages across it. What you and I fill the packages and gift baskets with is not insignificant. It must be luxurious food products, butter and cheese, fish conserves, a sausage, fruit juices, a bottle of wine, valuable things for which our brothers and sisters will thank us. (“Prima Abschrift”)

These packages of chocolate, coffee, and cigarettes continued to be sent long after the GDR had transformed itself into a prosperous, industrialized, and—from a purely caloric perspective—quite well-fed socialist country.[ii] By relegating the GDR to a state of permanent want, these shipments compounded the internalized model of inequality that was central to West German identity. Even at the peak of the GDR’s obesity epidemic in the 1970s and 1980s, these packages continued to flow across the border, targeting East German fantasies of the West rather than intending to address real food shortages. Throughout division and reunification, West Germans tended to depict East Germans as both chubby and badly dressed, exploiting a heavily class-based iconography that linked socialist bodies with the uneducated and unsophisticated proletariat.[iii] These poor-yet-overfed bodies represented a particular kind of “Cold War hunger” which allowed East Germans to be constructed as simultaneously hungry (needing food aid) and fat (lacking sophistication and knowledge about how to eat well).

The real food situation in the GDR was certainly different from that of the FRG, although as much in terms of the ways in which people acquired their food as the actual foods consumed. Rather than relying on well-stocked and reliable supermarkets, a hallmark of the West German economy, East Germans acquired their foods through a wide array of means. In addition to standard grocery shopping, food was acquired through an informal economy that included systems of barter and trade, the black market, favours, bribery, or personal connections—so-called “Vitamin B,” with B standing for Beziehungen or “relationships” (Schneider 250). Though the most severe supply problems had been resolved by the early 1960s, inadequate and monotonous food supplies continued to be a major political problem throughout the duration of the GDR. A 1968 report from the Leipzig Institute for Market Research found that “the lack of continuity in product supply is most noticeable in the structural differences between supply and demand,” noting that sheer quantity of goods was adequate for the population as a whole but distributed sporadically “in terms of time and territory” (Institut für Markforschung). A shop’s selection of goods was generally determined by geographic location; large cities, tourist destinations, or industrial regions were better supplied than smaller towns or areas with low population density. Nutritionists complained that inequitable and unreliable distribution policies not only insured constant dissatisfaction but did not serve the interests of public health (Vorschlag Nr 5). Unpredictability and recurrent shortages produced scarcity and consumer dissatisfaction that coexisted with low basic food prices, high caloric intake, and well-developed collective feeding programs for working adults and school children.

The extended life of rationing in the GDR meant that private food consumption did not increase as dramatically or as early as it did in the West. However, despite frequent shortages of individual foods, and countering West German assumptions of starvation and food deprivation, caloric intake remained quite high.[iv] In fact, shortages in staple products—especially butter and meat—often signaled excessive consumption rather than inadequate supply. As the populace had rising incomes and inadequate consumer goods to purchase, they frequently turned to foodstuffs, which were available abundantly if not always in the best quality or greatest variety. As a result, food quickly became one of the population’s most important outlets for spending (Steiner 186). In a development celebrated by East German politicians, if not the country’s nutritionists, the GDR’s per capita butter consumption had already outpaced that of the FRG by 1960 (Steiner 109).

In 1965, Der Spiegel bitingly noted that “the GDR—as always ten years behind progress—has finally reached the stage of the eating wave. Walter Ulbricht’s cherished dream of reaching global superiority has finally been realized—at least on the scale” (“Süß und fett”). Indeed, the FRG had begun reporting dangerous levels of obesity amongst certain segments of the population within two years of the country’s founding in 1949 (Bansi). In 1976, at the same time that the West German medical establishment was confirming obesity as the country’s most pressing medical threat, Die Zeit reported in open disgust that “obesity has gradually acquired an epidemic character” in the GDR, as “84,000 tons of excess fat are wobbling around” (“Gegen die Fettsucht”). The article, typical of West German discourse on East German obesity, diagnosed this excessive weight as being existentially different from the West’s own struggles with overweight citizens. West Germans were generally assumed to be too fat because of their booming economy’s excessive consumer choice. West German citizens, especially women, were thought to lack the willpower to resist the seductive call of abundant high-quality delicacies (Neuloh and Teuteberg). In dramatic contrast, socialist obesity was interpreted as a cipher of unfulfilled and displaced desires. In the East, food “makes up for difficulties, stresses, and disappointments. It is often a substitute for pleasures that one can no longer enjoy (“Gegen die Fettsucht”). This pathologized fatness—representing poverty and unhappiness rather than prosperity and pleasure—was a physical expression of the country’s flawed economy.

The association of the GDR with a distinctive sort of overweight was both true and untrue. While East German bodyweight steadily climbed over the postwar decades, and nutritionists agreed that the population’s diet was far too fatty and sweet and based on too much meat and too little produce, this was in fact not an East German but rather a German-German trend. Comparisons of the two countries’ diets were far more striking for their similarities than for their differences. East Germans ate more butter, flour, and potatoes than West Germans, roughly the same amount of sugar, meat, and milk, and, surprisingly, more vegetables—though primarily preserved and pickled—and much less tropical and citrus fruit. In addition, the two German states reported analogous levels of overweight. Different as the food landscapes of the two German states were, they both officially declared their obesity epidemics at roughly the same time. While both states began reporting rising levels of overweight by the mid-to-late 1950s, the 1970s ushered in talk of an epidemic. Both FRG and GDR studies during these decades consistently found that about one in three German adults was overweight (“Übergewicht als Risikofaktor;” Müller).

The Dilemma of Dieting in Socialism

#gallery-0-10 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-10 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-10 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-10 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Figure 2

While basic dietary intake as well as general rates of obesity resembled those of the FRG, the GDR’s struggle with overweight was indeed quite different from that of West Germany, discursively as well as in terms of policy. What were the specific contours of the East German struggle to control and reduce the country’s relatively high levels of overweight citizens? In the FRG, overweight went from being celebrated as an icon of economic success (see Economic Minister Ludwig Erhard, whose own bulk represented the abundance that marked the end of austerity and poverty) to being demonized as a working-class problem caused by a combination of laziness and ignorance. In the GDR, by contrast, a specific level of plumpness represented a proletarian sort of prosperity and social equality, while hunger signaled moral and economic failure. Much as they might have bemoaned excessive caloric consumption, socialist commentators never forgot, as chef Kurt Drummer pointed out in a bestselling cookbook promoting healthy, lower-fat recipes, that “after all we have not been living in this excess for so long. Less than two centuries ago cakes and tarts were still a luxury of which the poorer segments of the population generally could only dream” (Drummer and Muskewitz 172). East German “real-existing socialism” consistently rejected the West’s self-absorbed obsession with slimness, condemning the health harms of weight-loss pills and quack diets, as well as the rise of eating disorders among western youth as indicative of capitalism’s moral and societal flaws. By contrast, East Germany promoted an idealized worker’s body that was supposed to be attainable to all, neither thin nor fat, consuming neither too much nor too little, and focused on productivity rather than external appearance.

One of the earliest national studies of the spread of obesity in the East, published in 1970, estimated that one-third of the adult population was seriously overweight, while assuring its readers that it was “the high standard of living in the GDR” that was responsible for the “incredible spread of obesity” (Müller 1008). The study claimed that East Germans were overweight because “food is available everywhere—when among friends, it is practically forced upon you,” rather than, as in the West, being consumed inappropriately due to loneliness, familial degeneration, or isolation (Krebs 481). The head of the GDR Institute for Health Education explained that “our current health problems are the problems of a rich society, from the first we should see this, and for all complaints about the widespread overweight and the growing abuse of natural stimulants, we should not forget that, after all, we wanted this high quality of life and fought hard for it” (Voß 64). The fact that the GDR had the highest per capita rate of butter consumption in the world was a source of pride for government officials, while being anathema to nutritionists. This contradiction resulted in awkward constructions, as in the pamphlet “Your Diet, Your Health,” which claimed that “we are proud that in our state workers eat butter. But one must say to them that the exclusive consumption of butter can lead to health problems” (“Deine Ernährung, deine Gesundheit”). As a result, the GDR was much less consistent than the FRG in its official rejection of fatness, which remained medically condemned at the same time that it was considered aesthetically acceptable, a sign of prosperity and pleasure. While women’s magazines in the West were dominated by countless pages of dieting advice, East German women’s magazines made a point of encouraging readers to reject both fatness and thinness, instead modeling a moderate range that included the acceptable category of vollschlank (usually translated as “stout,” the word literally means “full-slim” or “big-slim.”) Public figures referenced abundant appetites and celebrated their paunches in a way unimaginable in the West. Even in the midst of the country’s obesity epidemic, traditional dieting continued to have negative associations, while abundant and carefree eating remained both norm and ideal.[v] While health professionals agreed that growing rates of overweight were a serious problem and health risk for the population, East Germans continued to see excess body weight as a cipher for abundant and tasty food, and thus proof of the country’s economic and social success.

In the GDR, a modern food economy was conceptualized as one of abundance, egalitarianism, collective wellbeing, and pleasure. East German health and nutrition experts repeatedly emphasized the close relationship between food and pleasure—something that is especially striking given the relative absence of this theme in equivalent West German sources. The German Hygiene Museum in Dresden, reflecting on how to get its citizens to eat both less and differently, reminded educators that “eating is a pleasurable experience, it belongs to the important pleasures of human life. One cannot underestimate the value of this pleasure. Speaking prohibitions with a raised finger prevents the necessary open-mindedness and willingness to change one’s own eating habits” (Brinkmann 65). Experts asserted that healthful eating and moderate dietary restraint did not mean “a society of thin ascetics with burning gaze who want everyone to live from a diet of black bread, yogurt, and radishes” (Haenel, “Fettsucht muss nicht sein”), and nutritionists were constantly reminding chefs and cookbook authors not to sacrifice flavor for health, something they described as a sure recipe for failure. Indeed, this celebration of the pleasure of eating, and especially the joys of “good taste,” reflected a political ideology that officially venerated the “ordinary” citizen and “normal” tastes. Thus, Honecker himself described his dietary lifestyle as a sort of model for socialist eating, combining an ascetic denial of exotic foodstuffs with an enthusiastic consumption of the simple yet distinctly unhealthy foods (meat, fat, starches), which nutritionists blamed for the country’s weight problems:

[E]very morning I ate one or two rolls with only butter and honey; for lunchtime I was in the Central Committee [canteen]; there I had either sausage with mashed potatoes, macaroni with bacon or goulash, and in the evenings I ate a little something at home, watched some TV, and went to sleep […]. Thus I never lost my connection to the Volk. (qtd. in Merkel, Wunderwirtschaft 314)

Such a celebration of simple, low-cost and high-calorie canteen meals was entirely absent from West Germany’s far more stringent language of crisis and self-control.

For nutritionists this official ideal posed a serious problem as they struggled to reconcile the country’s economic and social realities with their own recommendations for weight-loss. They complained that waging a serious fight against obesity would require a reversal of the country’s basic economic priorities, which generally equated high levels of popular consumption with economic as well as political success. While in the West diet products and reduced-calorie foodstuffs represented the potential for massive profit, in the GDR this was not the case. Politicians continued to associate both cheap food prices and high rates of food purchases with social and economic, if not medical, wellbeing. Diet foods, which generally required higher levels of industrial processing as well as the addition of artificial sweeteners and other relatively expensive and often imported chemicals, were a hard sell to socialist economists. In the early 1970s, when a Dresden cake factory developed a reduced-fat cream torte with 6,000 calories (reduced from the 9,000 in the original recipe), the additional labour costs were so substantial that the company’s production dropped dramatically (Bericht über den Stand der Qualität). The company requested a reduction in their production quota because their yearly productivity ratings were suffering; the threat of reduced profits won them permission to reduce production rates of their dietetic desserts as a result.

By the 1970s, rising rates of obesity had inspired medical experts to exert unprecedented pressure on the food industry to expand its dietetic offerings. At this point, East German factories were producing only 74 diabetic and “special diet” foods, 23 reduced-calorie items, and 35 healthy children’s food products (Ibid.). Ten years later, the number of such products had nearly doubled (Entwicklungskonzeptionen). In order to regulate this expanding market, the Trademark Association for Dietetic Products received increased funding for its ON stamp (optimierte Nahrung or “optimized food”), which was awarded to products that met a high standard of quality and healthfulness: reduced calorie, high fiber, low fat, reduced sugar, or diabetic-safe. A guide to dietetic food products shows the variants of ON labels being produced in the late 1970s. In the mid-1980s, 140 products were receiving the stamp, and this number continued to grow until 1990 (Ibid.). However, impressive as these official numbers were, the products available varied in quality and were always inadequate to meet popular demand.

#gallery-0-11 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-11 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-11 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-11 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Figure 3

East Germany’s difficulty with marketing weight-loss was both conceptual and economic. Especially problematic was the basic premise of encouraging people to simply eat less food. After all, the GDR’s much-vaunted subsidized food prices were explicitly designed to encourage high levels of (specific kinds of) food consumption, a goal inspired by the poverty and hunger of the interwar and postwar years. The rise in obesity, however, added fuel to older criticisms of the counterproductive consequences of artificially low food prices. Frozen prices on core goods led to subsidized commodities being seen as cheap rather than highly valued and, as a result, they were consumed in excess and wasted profligately.[vi] Nonetheless, economists worried that reduced food spending would leave citizens with no outlet for their excess cash. In the West, decreased food spending could be countered with increased spending on auxiliary dieting products, ranging from gym memberships to weight-loss pills or diet sodas. Such products were nearly nonexistent in the GDR. Indeed, food seemed to be the only thing that one could always buy, to the frustration of many East German dieters. In 1975, professional chef Claus Kulka wrote a letter blaming the country’s supply issues for his unsuccessful struggle to lose weight. After seeing a short TV clip composed by the German Hygiene Museum in Dresden on “healthy nutrition” he had been inspired to change his eating habits. The TV clip had recommended a calorie chart to regulate individual diet more precisely. However, such a chart proved impossible to find at a store or through mail-order, causing Kulka to ask angrily: “what use is it to us when healthy lifestyles are advocated by our media, but the simple and even cheap-to-produce products that are required cannot be found anywhere (Letter)?”

Nutritionists proudly claimed that “we are already capable of simulating meat so effectively that it cannot be distinguished from the natural product” (Haenel, An Frau Ilse Schäfer), asserting that these “simulated foods” would become especially popular among the overweight population by providing “much needed low-calorie alternatives” (Haenel, “Entwicklungen”). In reality, even simple reduced-fat sausages—which had been produced before the Second World War—were often difficult to come by. Despite official production quotas for over two dozen varieties of health-conscious sausages, a diabetic man complained in 1975 that it was:

incomprehensible why fine baked goods are made so excessively rich with sugar and fat, [and] the same is true for sausage. In general there is only one single variety of low-fat sausage. Who can eat this year after year? In special shops one can generally receive two to three sorts in exchange for standing in line for twenty minutes. All of them however are distinguished by a particular flavorlessness because they are all diet-sausage. (Betr: Diabetiker)

Even when the food industry did manage to develop and produce foodstuffs with reduced quantities of fats and sugars, this meant, counterproductively, that the East German market was flooded with these “unhealthy” waste products. A new variety of reduced-fat condensed milk with only four-percent fat promised, ironically, to also result in the production of “forty-seven tons of butter with seventy-four percent fat for [every] one thousand tons of condensed milk” —an equation of questionable health benefit (Beschluss); standard East German butter at the time had a fat-level of 70 percent. As much as nutritionists tried to guide and regulate food consumption, economic goals rather than nutritional ideals determined the foodstuffs that were produced.

Particularly galling was the fact that the East German media consistently affirmed the popular belief that prosperity was “connected to a high consumption of meat, butter, sweets made from refined flour, etc.” (Ein heisses Eisen). Magazines, newspapers, and other popular media explicitly rejected official nutritional recommendations to eat both less and differently, making it difficult to market alternative or healthier foods as “good.” As nutritionists complained:

[O]ccasionally we find support in the press, but often things there are made especially difficult for us. There were great difficulties with getting an article about whole grain noodles published in the newspaper. It was said, “with whole grain/dark noodles we are taking a step backwards, or this means that lean years are coming our way.” At this point a colleague spontaneously took a pot of whole grain noodles to the press and thus convinced the editorial board. (Gemeinschaftsküche 29)

In 1976, the popular magazine Guter Rat (Good Advice) casually defended its frequent inclusion of high-calorie recipes despite the growing levels of obesity by assuring that “for years our readers have enjoyed the little special occasion at which they occasionally present their guests with something special on the table. From this perspective we see absolutely no contradiction in the fact that we here exceed the caloric limits, and on the other hand speak of a healthy diet” (Editorial). Such popular venues defended high-calorie and purportedly unhealthy food choices as both normal and appropriate, suggesting that official nutritional recommendations were inadequate, unappealing, or just plain wrong.

A 1987 report on the psychology of dietary behavior blamed the food industry for negligible declines in obesity rates. The problem, the report found, was in the poor taste of the country’s dietetic foodstuffs. By trying to market these products to overweight citizens, the industry was ignoring the primal fact that “in dietary behavior the taste of foods and dishes and the affiliated satisfaction of the pleasure drive plays an essential role. This fact should be the basis for all decisions of those responsible for the food industry and food preparation to prepare tasty foods in the interest of a healthy diet” (“Psychologische Grundlagen”). On the other hand, nutritionists acknowledged that the better food tasted, the more people ate. Even as they worked to improve the quality and taste of the country’s food supply, nutritionists worried about numerous studies of consumer behavior that had found that improving grocery selection “stimulates private food production” and discouraged the use of canteens, which in turn meant that carefully calibrated reduced-calorie canteen meals would have far less impact than anticipated (Entwicklung des Bedarfs).

#gallery-0-12 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-12 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-12 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-12 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Figure 4

The country’s high levels of fatness and obesity-related illnesses suggested that the widespread availability of cheap and popular high-fat and high-sugar products was counterproductive. Anti-obesity campaigners attempted to sever the association of socialism with a sort of “comfortable,” even potentially attractive, sort of fatness. The East German Central Institute for Nutrition (Zentralinstitut für Ernährung) initiated a public debate asking “whether obesity is a private issue.” The answer was a resounding no, since “the consequences of obesity are so serious and impactful that one is dealing with a social, health, humanitarian, and economic problem of the first degree […] and beyond that the fat person certainly does not match our beauty ideal and seems unaesthetic, which one—including the fat person him or herself—is regrettably well aware of” (“Ist Fettleibigkeit Privatsache”). Dr. Helmut Haenel, the leading public figure in the country’s anti-obesity campaign, openly expressed his desire to make slim bodies the societal norm of the GDR. An egalitarian socialist society, according to Haenel, “cannot afford to maintain up to a third of its citizens, even up to a half, with heavy bodies, gasping for breath and unwilling to be active, susceptible to disease, less resistant to disease, early invalids, and early dying. A model society must also have the model of a healthy productive individual, that is, of a slim person” (Haenel, “Fettsucht muss nicht sein”). Such messages, however, did not have the desired impact. Although by the 1980s, surveys revealed that for the first time a majority of the population was trying to lose weight, these high rates of dieting actually correlated with higher rather than lower levels of obesity. By the time the Berlin Wall fell, the East German medical establishment, much like its capitalist counterpart, had come to see the population’s recalcitrant tastes as its biggest obstacle to popular health.

Conclusion

By the 1970s East and West German nutritionists ultimately agreed that obesity was their nation’s most pressing health threat. As a result, both socialist and capitalist experts believed that the goal of modern nutritional education was to tackle diet-related health problems through retraining popular tastes. Through a combination of propagandistic scare tactics and increased interventions in childhood and workplace diets, both states struggled throughout the 1970s and 1980s to change German tastes, and both admitted a discouraging lack of success (Weinreb, Modern Hungers). Thus, despite Western desires to assert profound differences in tastes and diets on either side of the Iron Curtain, East and West German tastes were far more similar than different, both in their stubbornness and their specific desires. The fall of the Wall changed the contours of these German struggles to regulate bodies and control popular taste. The disappearance of the GDR has meant for West Germans the disappearance of an “other” Germany that embodied the flaws of the “wrong” sort of food consumption and production. Yet food was a pivotal symbol during these tumultuous years. The importance of food in the complex memory work that has surrounded German reunification thus reflects the ways in which former East and West Germans have been struggling to come to terms with their divided past and shared present (Gries).

The importance of food for remembering the past and imagining the future at least partially explains why it is that foods and drinks are some of the only East German products still being produced in reunified Germany (Sutton); most other consumer products are no longer available (Merkel, “From Stigma to Cult” 264). This rekindling of interest in East German foods appears to many Westerners counterintuitive, if not absurd. For many West Germans, the GDR’s food culture seemed to be the aspect of everyday life that most graphically represented the horrors and failures of the former nation. Instead, the East German food landscape has become the focal point of distinctly positive memories and acts of recreation; it is a crucial, though underexplored, component of the phenomenon of a rise in nostalgia for the GDR—a sort of magical memory of the past that has grown to include many West Germans as well, who fetishize products of the imagined former East (Jarausch 336). Indeed, the continued prominence of foodstuffs in post-reunification constructions of the GDR—ranging from the Spreewald pickles of the blockbuster film Good Bye Lenin! to the revival of newly exotic “cult” classics such as the East German Rotkäppchen brand of sparkling wine or even the aforementioned Knusperflocken—remind us that food-based fantasies of the self and the other have proved longer lasting than the political divisions of the Cold War itself. More generally, this brief discussion of both internal and external debates over popular tastes in the socialist GDR also aims to suggest the importance of taste more generally for understanding the workings of state power. Modern states, regardless of their economic structure, strive to regulate their populations’ diets, while their nutritionists and economists inevitably struggle to reconcile the frustrating reality of individual tastes with such larger biopolitical projects.

Works Cited

Arbeitsgruppe Ernährung des Nationales Komitees für Gesundheitserziehung, editor. Ernährung – Gesundheit – Genuss: Praxis u. Wissenschaft. Warenverzeichnenverband Diätetische Erzeugnisse, 1986.

Bansi, H. W. “Die Fettsucht, ein Problem der Fehlernährung.” Probleme der vollwertigen Ernährung in Haushalts- und Großverpflegung, edited by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung, Umschau-Verlag, 1956.

Bericht über den Stand der Qualität neuer und weiterentwickelter Erzeugnisse für die rationelle Ernährung. Bundesarchiv (BArch), DF 5 / 1638.

Beschluss über die Ausarbeitung und Durchsetzung von Massnahmen der gesunden Ernährung, der Ernährungsaufklärung und Gesundheitserziehung in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik bis 1975. Bundesarchiv (BArch), DG 5 / 823.

Betr: Arbeitsgruppe “Lebensmittelindustrie” (June 21, 1956). Landesarchiv Berlin, B Rep 010 02 / 316.

Betr: Diabetiker, (1975). Bundesarchiv (BArch), DQ 1 / 10550.

Betts, Paul. The Authority of Everyday Objects: A Cultural History of West German Industrial Design. U of California P, 2007.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Harvard

UP, 1984.

Brinkmann, L. “Ernährungsinformation in Tageszeitungen, Wochenschriften, Magazinen.” Arbeitsgruppe Ernährung, pp. 65-68.

Ciesla, Burghard, and Patrice Poutrus. “Food Supply in a Planned Economy.” Dictatorship as

Experience: Towards a Socio-Cultural History of the GDR, edited by Konrad Jarausch, Berghahn, 1999, pp. 143-62.

“Deine Ernährung, deine Gesundheit” (1960). Sächsisches Staatsarchiv Dresden, WA-F 1160 Nr. 163.4, Bd. 1.

Drummer, Kurt, and Käthe Muskewitz. Kochkunst aus dem Fernsehstudio: Rezepte – praktische Winke – Literarische Anmerkungen, Fachbuchverlag, 1968.

Editorial. Guter Rat, no. 3, 1976, p. 1.

“Ein heisses Eisen? Ernährungsberatung” (1959). Deutsches Institut für Ernährungsforschung, Potsdam (DIfE), Box Nr. 104.

Die Entwicklung des Bedarfs in ausgewählten Bereichen der Gemeinschaftsverpflegung und in öffentlichen Gaststätten der Hauptstadt der DDR Berlin bis 1980 (1971). Bundesarchiv (BArch), DL10 2 / 595.

Entwicklungskonzeptionen zur Versorgung der Bevölkerung mit diätetischen Lebensmitteln bis 1990 (June 1984). Bundesarchiv (BArch), DF5/1588.

Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, editor. Der Alltag in der DDR, Verlag Neue Gesellschaft, 1986.

“Gegen die Fettsucht der Genossen.” Die Zeit, March 5, 1976.

Die Gemeinschaftsküche. Freier Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (FDGB), 1957.

Goody, Jack. Cooking, Cuisine and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology. Cambridge UP, 1982.

Gries, Rainer. “Geschmack der Heimat.” Deutschland-Archiv 27, October 1994, pp. 1041-58.

Haenel, Helmut. [An Frau Ilse Schäfer.] Deutsches Institut für Ernährungsforschung, Potsdam (DIfE), Box Nr. 233.

—. “Entwicklungen auf dem Gebiet neuer Nahrungsmittel” (1968). Deutsches Institut für Ernährungsforschung, Potsdam (DIfE), Box Nr. 229.

—. “Fettsucht muss nicht sein” (1970). Deutsches Institut für Ernährungsforschung, Potsdam (DIfE), Box Nr. 233.

Härtel, Christian, and Petra Kabus. Das Westpaket: Geschenksendung, keine Handelsware. Ch. Links, 2000.

Holtmeier, H. J. “Ernährungsprobleme der Gegenwart.” Die Agnes Karl-Schwester, Der

Krankenpfleger, vol. 21, no. 8, 1967, pp. 309-12

Horbelt, Rainer, and Sonja Spindler. Die deutsche Küche im 20. Jahrhundert: Von der Mehlsuppe im Kaiserreich bis zum Designerjoghurt der Berliner Republik: Ereignisse, Geschichten, Rezepte. Eichborn, 2000.

Institut für Marktforschung, Leipzig. “Die künftige Entwicklung der Verbrauchererwartungen an das Sortiment, die Bearbeitung, die Qualität und die Verpackung der Nahrungsmittel” (January 1, 1968). Bundesarchiv (BArch) DL102/189.

“Ist Fettleibigkeit Privatsache?” (1970). Deutsches Institut für Ernährungsforschung, Potsdam (DIfE), Box Nr. 233.

Jarausch, Konrad. “Beyond the National Narrative: Implications of Reunification for Recent German History.” Historical Social Research, vol. 24, no. 4, 2012, pp. 498–514.

Kaminsky, Annette. Wohlstand, Schönheit, Glück: Kleine Konsumgeschichte der DDR. Beck, 2001.

Kerr-Boyle, Neula. “Orders of Eating and Eating Disorders: Food, Bodies and Anorexia Nervosa in the German Democratic Republic, 1949-90.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University College London, 2012.

Krebs, W. “Gibt es eine rationelle Behandlung der Fettsucht.” Das deutsche Gesundheitswesen, vol. 21, no. 11, 1965, pp. 481-83.

Kulka, Claus. [Letter 1975]. Bundesarchiv (BArch), DQ 1 / 10550.

Merkel, Ina. “From Stigma to Cult: Changing Meanings in East German Consumer Culture.” The Making of the Consumer: Knowledge, Power and Identity in the Modern World, edited by Frank Trentmann. Berg, 2006, pp. 249-70.

—. Wunderwirtschaft: DDR-Konsumkultur in den 60er Jahren. Bohlau, 1996.

Müller, Friedrich. “Zur Verbreitung der Fettsucht in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik.” Zeitschrift für die gesamte innere Medizin und ihre Grenzgebiete, vol. 22, no. 15, 1970, pp. 1001-09.

Neuloh, Otto, and Hans-Jürgen Teuteberg. Ernährungsfehlverhalten im Wohlstand: Ergebnisse einer empirisch-soziologischen Untersuchung in heutigen Familien-haushalten. Schoeningh, 1979.

“Prima: Abschrift” (December 1953). Bundesarchiv [BArch], B 116 / 8075.

Proust, Marcel. Remembrance of Things Past. Vintage, 1982.