#but scottish independence is fundamentally about the fact that scots cannot live the way they want to because of our political system

Text

listen now. i am under no illusions that most pro-scottish independence memes on this hellsite are likely spread without a lot of thought put into it. maybe you hate the idea of monarchic statehood. maybe you think the uk’s right-wing government causing a constitutional crisis over trans folk being able to complete a legal process a little easier is exceptionally funny.

but as someone who’s campaigned for independence for nearly half her life (started at 16 and i’m about to turn 31); it just... it means a lot. even if it’s fleeting, even if its a notional solidarity. living in scotland so often feels like a constant test of your critical thinking skills. scots are taught from an an early age that our language doesn’t exist, that our culture or heritage isn’t as important to learn about as british or global history. we’re taught, in many ways, that we’re just funny sounding english people with a propensity for drinking and ceilidh dancing. we’re constantly manipulated by the mainstream british media which we’re trained to believe is some of the most non-biased in the world (particularly the BBC). we don’t know who we are or where we came from as a nation. and if you’re not paying attention and asking questions, it is so goddamn easy to believe this piss state is better. it’s a lie we’ve been beating into ourselves for hundreds and hundreds of years.

it’s sometimes hard to see outside the bubble and remember that other people looking in might see what so many of us on the inside see. so thank you. even your damn bugs bunny memes have warmed my hardened little heart on this january eve.

#its fun to observe the whole anti monarchy swing on tumblr because yeah fuck that family#but scottish independence is fundamentally about the fact that scots cannot live the way they want to because of our political system#the uk is a 'partnership of equals' except one partner has its boot on the other partner's neck(s)#and to cover my ass - what i'm describing is only my experience#i was forced to stop speaking scots aged five in school#i didn't read ANY scots literature beyond burns until i went to university and studied it bc it wasn't mandatory#i did like... a project on mary queen of scots in primary school and a 3 month module on the clearances in high school and that was IT#everything i know about scots literature culture language and politics i had to learn myself because there was no commitment to teach it#(this might have changed but i doubt the needle has moved significantly)#im just so very tired of fighting the fight right now#the GRA veto has really done a number on me#mutuals who rb pro-indy posts just know i want to kiss you (consensually) whole on the mouth xoxoxox

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

19th March 1286: “A Strong Wind Will Be Heard in Scotland”

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

On 19th March 1286, a body was discovered on a Fife beach, not far from the royal burgh of Kinghorn. The corpse was that of a 44-year-old man, and the cause of death was later diversely reported as either a broken neck or some other severe injury consistent with a fall from a horse at some point during the previous night. It is not known exactly when this body was found, nor do we know who discovered it. But we do know that the dead man was soon identified, with much dismay, as the King of Scots himself, Alexander III.

The late king had no surviving children, only a young widow who was not yet known to be pregnant, and an infant granddaughter in the kingdom of Norway. Despite this, Alexander III’s untimely death did not cause any immediate civil strife, although it did set in motion a chain of events which eventually led to the Scottish Wars of Independence. This conflict would forever alter the relationship between the kingdoms of Scotland and England, as well as the wider course of European history.

Although Alexander III was a moderately successful monarch, he had been unfortunate over the last ten years. His first wife, Margaret of England, had died in 1275 and Alexander initially showed no immediate interest in remarriage. At first the succession seemed secure: Margaret had left behind two sons and a daughter. However the death of the couple’s younger son David c.1281, may have prompted the king’s decision to arrange the marriages of his two surviving children over the next few years. In the summer of 1281, the twenty-year-old Princess Margaret set sail for Bergen, where she was to marry King Eirik II of Norway. Her brother Alexander, the eighteen-year-old heir to the throne, married the Count of Flanders’ daughter in November 1282. Neither marriage lasted long. The queen of Norway died in spring 1283, possibly during childbirth, while her younger brother succumbed to illness in January 1284. Within a few years, a series of unforeseen tragedies had destroyed Alexander III’s family and hopes, and the outlook for the kingdom seemed equally bleak...

All was not lost however. The king was in good health and believed he could count on the support of the realm’s leading men. Steps were swiftly taken to ensure their compliance with his plans for the succession. On 5th February 1284, a few weeks after Prince Alexander’s death, an impressive number of Scottish nobles* set their seals to an agreement at Scone. In the event of the king of Scotland’s death without any surviving legitimate children, they obliged themselves and their heirs to accept as monarch the heir at law. This was currently a baby named Margaret, the only surviving child of Alexander III’s daughter the queen of Norway.

(Drawing based on a seal belonging to Yolande of Dreux, Alexander III’s second queen. She later became Countess of Montfort and, by marriage, Duchess of Brittany. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the bishops of Scotland were to censure anyone who broke this oath, the prospect of the crown being inherited by an infant girl on the other side of the North Sea was obviously not ideal. Her grandfather struck an optimistic note in a letter to his brother-in-law Edward I of England, writing that in spite of his recent “intolerable” trials, “the child of his dearest daughter” still lived and hoping that “much good may yet be in store”. But the king would not leave everything up to chance and in October 1285, at the age of 43, he married the French noblewoman Yolande of Dreux. As the year drew to a close, Alexander might have hoped that his misfortunes were behind him. He still had his kingdom and his health, and now, with a new queen, there was every chance that he could father another son.

In fact, the king had less than six months to live. The exact circumstances of Alexander’s death are shrouded in mystery, although most sources agree on the fundamental details. Only the Chronicle of Lanercost gives a detailed account, although much cannot be corroborated, and its author had a habit of providing moral explanations for historical events. He was convinced that the calamities which befell the Scottish royal house in the 1280s were punishment for Alexander III’s personal sins. The chronicler never explicitly names these sins, but he does hint at a conflict between the king and the monks of Durham (allowing Alexander’s death to be attributed to a vengeful St Cuthbert). The chronicler also included salacious stories of Alexander’s private life, claiming:

“he used never to forbear on account of season or storm, nor for perils of flood or rocky cliffs, but would visit, not too creditably, matrons and nuns, virgins and widows, by day or by night as the fancy seized him, sometimes in disguise, often accompanied by a single follower.”

Although this does seem to back up the king’s habit of making reckless journeys, alone and in bad weather, the chronicle’s biases are nonetheless fairly obvious. On the other hand, the man who probably compiled the chronicle up to the year 1297 does appear to have had many contacts in Scotland. These included the confessors of the late Queen Margaret and her son Prince Alexander, as well as the latter’s tutor, the clergy of Haddington and Berwick, and the earl of Dunbar. It is unclear how he acquired information about Alexander III’s death, but the chronicle’s narrative is at least plausible and correct in its essentials. Although some of the anecdotes are a little too detailed and didactic to be entirely truthful, the narrative provides some interesting insights into contemporary behaviour, such as the way medieval Scots felt entitled to address their kings. In the absence of alternative narratives, and without necessarily subscribing to the chronicler’s moral views, it is therefore perhaps worth following Lanercost to begin with, supplementing this with additional information where possible.

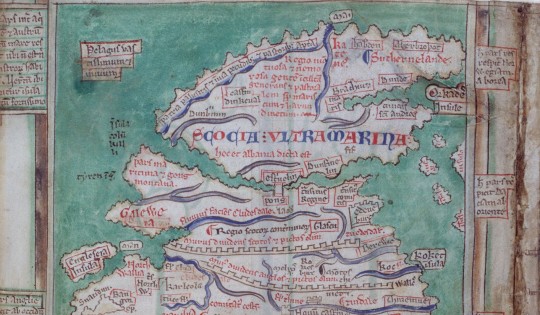

(The northern half of a map of Britain, drawn by the thirteenth century English chronicler Matthew Paris. Matthew Paris was based in the south of England and was not overly familiar with Scottish geography, but his depiction of Scotland as split over two islands and joined only at the bridge of Stirling, is nonetheless enlightening. The map is now in the public domain and has been made available by the British Libary (x))

On the evening of 18th March 1286, Alexander III is reported to have been in good spirits. This was in spite of the weather, which the author of the Chronicle of Lanercost described as being so foul, “that to me and most men, it seemed disagreeable to expose one’s face to the north wind, rain and snow”. The king of Scots was then dining at Edinburgh, attended by many of his nobles, who were preparing a response to the king of England’s ambassadors regarding the aged prisoner Thomas of Galloway. However when the court had finished dinner King Alexander was not at all anxious to retire early. Instead, not in the least deterred by the wind and rain lashing the windows, he announced his intention of spending the night with his new wife. Since Queen Yolande was then staying at Kinghorn in Fife, travelling there from Edinburgh would not only involve riding over twenty miles in the dark, but would also mean crossing the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth. Unsurprisingly, the king’s councillors tried to dissuade him. However Alexander was determined, and eventually he set off with only a few attendants, leaving his courtiers wringing their hands behind him.

The first part of the journey passed without incident and soon the king and his companions arrived at the Queen’s Ferry, by the shores of the Forth. This popular crossing point was named after Alexander’s famous ancestress St Margaret, who had established accommodation and transport for pilgrims there two hundred years earlier. But when the king himself sought passage, the ferryman pointed out that it would be very dangerous to attempt the crossing in such conditions. Alexander, undeterred, asked him if he was scared, to which the ferryman is said to have stoutly replied, “By no means, it would be a great honour to share the fate of your father’s son.” So the king and his attendants boarded the ferry and, notwithstanding the storm, the boat soon reached the shores of Fife in safety. As the king and his squires rode away from the ferry port, intending to complete the last eleven or so miles of their journey that night, they passed through the royal burgh of Inverkeithing. There, despite the evening gloom, the king’s voice was recognised by the manager of his saltpans, who was also one of the baillies of the town.** The burgess called out to the king and reprimanded him for his habit of riding abroad at night, inviting Alexander to stay with him until morning. But, laughing, Alexander dismissed his concerns and, asking only for some local serfs to act as guides, he rode off into the night.

(South Queensferry, as drawn by the eighteenth century artist John Clerk and made available for public use by the National Galleries of Scotland. Obviously the Queen’s Ferry changed a lot between the 1280s and the 1700s, but at least during this period the ferry was still the main mode of transportation across the Forth.)

By now darkness had set in and, despite the local knowledge of their guides, it was not long before every member of the king’s party became completely lost. Although they had become separated, the king’s squires eventually found the road again. However at some point they must have realised that they had a new problem: the king was nowhere to be found.

In the early fifteenth century, local tradition held that Alexander was at least heading in the right direction when he became separated from his companions. Although he too had lost sight of the main road, the king followed the shoreline, his horse carrying him swiftly over the sands towards Kinghorn. It was there, only a couple of miles from his destination, that the king’s luck finally ran out. Since there were no known witnesses to Alexander III’s death, it is unlikely that we will ever know for certain what happened that night. However most sources agree that the king’s horse probably stumbled and threw its rider. Alexander tumbled to the ground and snapped his neck and, at a stroke, the dynasty which had ruled Scotland for over two hundred years came to an end.

It is not known precisely how long the king’s body lay on the beach, alone under the moon while the waves crashed on the shore and confusion reigned among his squires and guides. However his corpse was discovered the next day and was swiftly conveyed to nearby Dunfermline. Ten days later, on 29th March 1286, the kingdom’s ruling elite gathered to see the last King Alexander buried near the high altar of the abbey kirk, in the company of his ancestors. Near the spot where the king’s body was allegedly found, a stone cross was later erected beside the road, which could still be seen by travellers over a hundred years later. The modern belief that Alexander III died when either he or his horse fell from a cliff*** (a tradition which is not supported by any mediaeval sources so far as I am aware) may stem from the position of this old cross, which possibly occupied the same spot as that of the Victorian Alexander III monument. This monument can now be seen at the side of the modern A921 road between Burntisland and Kinghorn, a permanent reminder of the role this seemingly nondescript location once played in the history of Scotland.

(The Alexander III monument near Kinghorn. Source: Wikimedia Commons- the photo was taken by Kim Traynor who has kindly made the image available for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

The impact of Alexander’s death on a small mediaeval kingdom like Scotland, conditioned to look to its monarch for leadership, must have been great. Even the Lanercost chronicler admitted that the general populace was observed “bewailing his sudden death as deeply as the desolation of the realm.” However it is important not to exaggerate the scale of the crisis. Popular views of Alexander III’s death are inescapably informed by the accounts of fourteenth and fifteenth century writers, who depicted it as the root of all of Scotland’s later ills.

Writing in the aftermath of a century dominated by war, plague, famine, and climate change, it is perhaps unsurprising that many late mediaeval chroniclers looked back on Alexander III’s reign as comparatively peaceful. As the author of the fourteenth century “Gesta Annalia II” explained, “How worthy of tears and how hurtful his death was to the kingdom of Scotland is plainly shown forth by the evils of after times.” Meanwhile, in his “Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland” completed c.1420, Andrew Wyntoun portrayed Alexander’s reign as a Golden Age of peace and justice (when, just as importantly, oats only cost fourpence a boll). He incorporated an old song into his chronicle, perhaps written in the years following the king’s accident, which neatly encapsulates later views of the event and its impact:

“Quhen Alysandyr oure Kyng wes dede

That Scotland led in luẅe and lé,

Away wes sons off ale and brede,

Off wyne and wax, off gamyn and glé:

Oure gold wes changyd in to lede.

Cryste borne in to Vyrgynyté,

Succoure Scotland and remede,

That stad [is in] perplexyté.”

Wyntoun’s younger contemporary Walter Bower, author of the “Scotichronicon”, also lamented Alexander’s premature death and even rolled out a legend about Scotland’s famous seer, Thomas the Rhymer, to reinforce his point. On 18th March 1286, he claimed, the earl of Dunbar “half-jesting” asked the Rhymer for the next day’s weather forecast. True Thomas answered gloomily:

“Alas for tomorrow, a day of calamity and misery! Because before the stroke of twelve a strong wind will be heard in Scotland, the like of which has not been known since long ago. Indeed its blast will dumbfound the nations and render senseless those who hear it, it will humble what is lofty and raze what is unbending to the ground.”

The next morning came and went without any gales, so the earl decided that Thomas had gone mad- until a messenger arrived at precisely midday with news of the king’s death. Although Bower may have been attempting to bolster Thomas of Erceldoune’s reputation as a prophet (in response to English propagandic use of Merlin’s prophecies), the anecdote reveals the significance he attached to Alexander III’s death. Similarly for John Barbour, author of the fourteenth century romance “The Bruce”, there was no doubt that the story of his hero’s story began, “Quhen Alexander the king was deid / That Scotland haid to steyr and leid.” Following this, Barbour skips ahead to the selection of John Balliol as king, dismissing the six years in between as a time when the country lay “desolate”. In this way later chroniclers created the impression of an Alexandrian ‘Golden Age’ and that Scotland almost immediately descended into chaos after his death. Though understandable, these late mediaeval interpretations have traditionally hampered analysis of Alexander’s reign and the events of the decade following his death, despite the best efforts of modern historians.

(The coronation of the young Alexander III at Scone, as depicted in a manuscript version of the fifteenth century “Scotichronicon”, compiled by the Abbot of Incholm, Walter Bower. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In reality, while the king’s death was undoubtedly a deep blow, the Scottish political community rallied in the immediate aftermath. In April 1286, parliament assembled at Scone and promised to keep the peace on behalf of the rightful heir to the kingdom. Six ‘Guardians’ were to govern in the meantime- two bishops (William Fraser of St Andrews and Robert Wishart of Glasgow), two earls (Alexander Comyn, earl of Buchan and Duncan, earl of Fife), and two barons (John Comyn of Badenoch and James the Steward). Despite the oaths sworn to Margaret of Norway two years earlier, there may have been some doubt as to who the “rightful heir” actually was. Certain sources claim that Alexander III’s widow Yolande of Dreux was pregnant and the political community waited anxiously for several months before the queen gave birth in November 1286. However no male heir materialised**** and by the end of the year it seems to have been generally acknowledged that the three-year-old Maid of Norway was the rightful “Lady of Scotland”. She was destined never to set foot in Scotland, but, despite her age, gender, and absence from the realm, the country did not descend into complete anarchy in the four years when she was the accepted heir to the throne. Undoubtedly there were people who had reservations about her reign: the Bruces, for example, seem to have attempted a short-lived rebellion, though the situation was soon defused by the Guardians. By 1289 the cracks were perhaps beginning to show, with the death of the earl of Buchan and the murder of the earl of Fife removing two Guardians, who were not replaced. Nonetheless, the authority of the Guardians was recognised in the absence of an adult ruler and they generally attempted to govern competently in the four years between Alexander III’s accident and the Maid of Norway’s own death in 1290.

Having received news of this second tragedy, the Guardians again acted cautiously, deciding that rival claims for the kingship should be judged in an official court chaired by a respected and powerful arbitrator. Thus they appealed to Scotland’s formidable neighbour, Edward I of England. Despite later allegations of foul play, the English king’s eventual judgement in favour of John Balliol does appear to have been consistent with the law of primogeniture and due process. It would take years of steady deterioration before war finally broke out in 1296. By then Alexander III had been dead for a decade, and though the crisis may have indirectly grown out of his demise, it was not necessarily the immediate cause of Scotland’s late mediaeval woes. Nonetheless the events of that dark night in March 1286 would leave their mark on the popular imagination for centuries, shaping Scottish history down to the present day.

(An imprint of the Great Seal used by the Guardians of Scotland following Alexander III’s death. Reproduced in the “History of Scottish seals from the eleventh to the seventeenth century”, by Walter de Gray Birch, now out of copyright and available on internet archive)

Additional Notes:

*The assembled magnates included the earls of Buchan, Dunbar, Strathearn, Atholl, Lennox, Carrick, Mar, Angus, Menteith, Ross, Sutherland, and two other earls whose titles are illegible but who may have been Caithness and Fife. The barons included Robert de Brus the elder (father of the earl of Carrick and grandfather of the future Robert I), James Stewart, John Balliol (the future king), John Comyn of Badenoch, William de Soules, Enguerrand de Coucy (Alexander III’s maternal cousin), William Murray, Reginald le Cheyne, William de St Clair, Richard Siward, William of Brechin, Nicholas de Hay, Henry de Graham, Ingelram de Balliol, Alan the son of the earl, Reginald Cheyne the younger, (John?) de Lindsay, Simon Fraser, Alexander MacDougall of Argyll, Angus MacDonald, and Alan MacRuairi, among others.

** The historian G.W.S. Barrow identified this figure as Alexander the saucier the master of the royal sauce kitchen and one of the baillies of Inverkeithing.

*** There are some variations on this local tradition too- in 1794, the minister who wrote the entry for Kinghorn parish in the Old Statistical Account claimed that the ‘King’s Wood-end’ near the site of the current Alexander III monument was where the king liked to hunt and that he fell from his horse while on a hunting trip.

****The Guardians and other nobles may have assembled at Clackmannan for the birth. Several modern historians have accepted Walter Bower’s statement that the queen’s baby was stillborn, despite the Chronicle of Lanercost’s somewhat fantastic tale of a fake pregnancy, with Yolande being caught conspiring to smuggle an actor’s son into Stirling Castle.

Selected Bibliography:

- “The Chronicle of Lanercost”, as translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, Volume 2, ed. Joseph Bain

- Rymer’s “Foedera…”, Volume 1 part 1

- “Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland”, vol 1., ed. Joseph Stevenson

- “Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers”, ed. A.O. Anderson (especially Annals of Worcester; Thomas Wykes; Chronicles in Annales Monastici)

- “Early Sources of Scottish History”, ed. A.O. Anderson (esp. Chronicle of Holyrood, various continuations of the Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland; John of Evenden; Nicholas Trivet)

- “The Flowers of History… as Collected by Mathew of Westminster”, ed. C.D. Yonge - Gesta Annalia II (formerly attributed to John of Fordun) in “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, ed. W. F. Skene

- John Barbour’s “The Brus”, ed. A.A.M. Duncan

- “The Orygynale Cronikil of the Scotland”, vol.2., by Andrew Wyntoun, ed. David Laing

- “A History Book for Scots: Selections from the Scotichronicon”, ed. D.E.R. Watt

- “The Authorship of the Lanercost Chronicle”, by A.G. Little in the English Historical Review, vol. 31 no. 122, p. 269-279

- “The Kingship of the Scots”, A.A.M. Duncan

- “Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland”, G.W.S. Barrow

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1230-1371”, Michael Brown

I have extensive notes so if anyone needs a reference for a specific detail please let me know.

#Scottish history#British history#Scotland#thirteenth century#Mediaeval#Middle Ages#1280s#Alexander III#Yolande of Dreux#House of Canmore#Margaret of England#Margaret Maid of Norway#Margaret of Scotland Queen of Norway#Prince Alexander (d.1284)#Edward I of England#William Fraser Bishop of St Andrews#Robert Wishart Bishop of Glasgow#John Comyn of Badenoch#Alexander Comyn Earl of Buchan#James the Steward#Duncan Earl of Fife (d.1288)#Chronicle of Lanercost#Patrick III Earl of Dunbar#Walter Bower#Scotichronicon#Andrew Wyntoun#John Barbour#John of Fordun#Gesta Annalia II#Sources

37 notes

·

View notes

Link

I stumbled across this article on twitter the other day and IMO it represents simultaneously the worst and most socially positive elements of what a lot of people think about when they think about scottish independence. Im from Scotland and support independence in the current climate, but for a variety of reasons, some of which are identical to the standard pro-indy platform, some wildly divergent.

It starts off well enough, by poking a few holes in Ruth Davidsons generally tepid takes on the broad campaign for independence as well as highlighting her hypocrisy as regards her take on nationalism in general ( cue timely reference to the infamous tank photograph). After this the author takes the tack of using this as a platform for arguing for: “ ...the independence movement to challenge her "thinking" (quote marks very much needed) by giving stronger and more coherent meaning to the philosophy of our cause.“

Which in general is a program i support, especially given that the nature of the mainstream lines of the debate have sort of solidified into entrenched positions since indyref 1.0. However Im broadly speaking an anarchist so any chance of my actual views getting into the rhetoric of the independence debate is pretty slim. Regardless we crack on and Mr Mcalpine immediately starts talking about academic theories and conceptions of nationalism, which i would agree is a fair point to start. However this is also where i start to run int trouble with this article. Instead of using the theories he has outlined to help approach the matter materialistically and even state which of these he believes is closer to accuracy ( though to be fair he does do this later), McAlpine immediately simply lays them out as an offering and moves on to his first major calumny. I find it fitting that he does this after making the error that all online anarchos love to point out : “ oooooh you assumed the nation state is a good model at ALL. you FOOL” etc etc

So what is this first major issue? well:

“Because here's the thing – there is more or less no person in the world who is not wholly reliant on and deeply committed to the nation state system. I get deeply irritated by the 'citizen of the world' crowd who, hypocritically, expect someone else's nation state to provide the police to protect their MacBooks as they check into a hotel in someone else's country using someone else's roads paid for by someone else's nation state raising taxes on their population.

If you are a fascist, an anarcho-syndicalist, a theocrat or a believer in undemocratic kingdoms or empires, or of a single world government, then you have taken a legitimate position from which to attack nationalism. Everyone else is some kind of nationalist.”

Fuck me, bad post op.

First of all this is, for someone who just ragged on Ruth Davidson for not knowing about academic theories of nationalism in human society, this guy displays a total absence of knowledge when it comes to literally any of the ideological positions he’s just listed. Secondly, given the way this guy seems to conceive of nationalism i find the ( I assume rhetorical) claim he makes that “everyone is some kind of nationalist” to be somewhat farcical. Some people deliberately extricate themselves form this mode of thinking. some never fall into it at all and others merely drift away. Its either that or he is going for the Orwell argument, in which case, buddy, me and my pal Max have some news for you.

On the other hand if McAlpine is making the argument that “ we all live within political systems pervaded by the importance of the nation-state” or something along those lines, then frankly that’s one hell of a circular point seeing as he proselytizes the idea of Nation States as inherently legitimate, or at least seems to. If this latter argument is being made here then its not wildly different to that time Louise Mensch got up of Have I Got News For You and complained that anti capitalists protesters were idiots because they’d probably consumed capitalist goods.

Not least i find this disgusting because of his insistence on the conception of “our roads” as if humans can cut out cubes of the air and trademark them. A criticism of tourist-colonialism is very justified, i agree, and the idea that the colonized nation, repressed by the colonizer is legitimate in resistance is one that many would say carries some water, but here he turns it utterly on its head, not only by arguing that Scotland is in any way similar to being an imperial colony in any significant degree, but also by turning this argument into a complete unconscious capitulation to the essentialism of the republic. Mcalpine worships the citizen, and now because of it anyone can build upon that ideological failure to wring up whatever evolved form of essentialism they may choose. It is from this that the whole failure of much of the self described civic nationalists springs. Their ideology has replaced the old totem with a new one and now the imagined republic forms what they strive for. It will of course never exist, vote or no. I happily voted Yes once and will do so again, but while i described myself as a civic nationalist last time i don’t any longer. I dont think this article really vindicates why anyone should

In that it is treated differently within the UK political landscape by the powers that be it is more akin to a collection of low priority constituencies, safe seats that neither side is compelled to compete over and thus will not invest in. The vestiges of serious English/Scottish violent tension or the post 1707 internal repression are not actually materially important any more. Scots aren’t being brutally oppressed in that way any more. In the Current material conditions it is about austerity over the course of decades, the aftermath of industrial collapse and regrowth, and cutting away from the worst of liberalism and neoliberalism, into a situation where things are merely bad and not catastrophic.

its for this reason that im skeptical of the premise of his next section: that civic, cultural and ethnic nationalism are fundamentally different. Different they are, but not inextricably so. in fact i believe they are merely faces of each other, and because the idea of nationalism does not allow for people to actually escape that loop, are suited to merely melt into each other as the climate requires. If you cant imagine the “ someone elses roads” rhetoric coming out of the mouth of certain other UK political figures mouths. Mcalpine attempts to escape this by stating that he sees the shades of grey and the nuances inherent in the problems of all these theories, but i would argue that the three distinct ideas of nationalism he has outlined do not form separate trends or tendencies, but that they chase each other in a spiral. I believe they have a dialectical relationship.

(Getting wildly off the rails I would liken it to Clausewitz’s “ fascinating trinity”, where three separate components of a concept that at first glance each seem the essential component, each rely on each other and by their own presence force the other aspects to relate to them.* The actual philosophical difference between civic and ethnic nationalism is particularly tenuous for reasons which i should not have to elucidate. These are not separate categories. They are elements in dialectical conversation with each other and each exists in the nationalist ideal, if you look in the right places. Creating a theory of the modern nation state isn't like picking different pokemon at the start of the game)

*I am aware of course that this is obscure as hell. feel free to ignore it

Anyway getting back on track: I think that by this point another key error in the Civic nationalist platform should be clear by now: the notion that civic nationalism stands somehow as a desperately radical stance against globalization and modern consumerism, or even that it would materially represent a desperately different way of being from such things. Neither of these things are really expressly mentioned in this article as it isn't really the place for that massive discussion yet i personally get the feeling that we should briefly discuss them nonetheless. The Civic nationalist tendency amongst the main camp of the Independence movement in Scotland frequently effectively offers Scottish nationalism/independence as a bulwark, both materially and ideologically against “ the bad capitalism” presuming their own to be so much better. Again this isn't mentioned in McAlpines article, so its not like its at all his fault but i feel the need, as someone in favor of Independence and as an anti-capitalist who takes a Marxian analysis of capitalist economics to reiterate that this position is blatant nonsense

Anyway Mcalpine then knocks it right out of the park with the inclusion of a joke YouTube video, which to be fair takes a nice swing at BBC British nationalist propaganda, which is to be fair pretty horrendous. This section is a little edgy but whatever. He then moves on to complain that Sturgeon has had to avoid the word “ nationalist” in her rhetoric. Frankly i normally have no problem with the idea of nationalism being unpopular, but his point that it is being made unusable by the deliberate propagandist manipulation of the silent nationalism of the British political landscape (lmao) is an accurate one. Nationalism isn't what those people are arguing against. they are arguing for their own nationalism and their own power.

Next up, after this worthwhile insight is a quite positive point, the heart of which i understand but at same time cannot stand alongside: The fixed idea of the citizen and citizenry is again raised. Difference and the validity of such is celebrated. All is Utopian. All is then sacrificed. the preponderance of the nation state over the citizen immediately re-erupts onto the scene, as the citizens become components of the national project. Which is inevitably going to cave to bog standard capitalist exploitation no matter how Utopian you make your Tomorrow-Scotland. Surplus Value is still Surplus Value regardless who the extractor is. McAlpine is not willing to accept this however and states:

“ This means that I believe nationalism is a function of people – that the nation state is explicitly a contract between each of its citizens, and not a contract between individuals and 'the state'. “ ...to which i can only respond with “ yeah right”.

He reiterates his imagined distinction between movement for a nation of citizens and affinity groups and relations, and old school patriotism and rightly criticizes it as a subservience to power, yet fails to reflect on such a notion within a nation.

The rest of this article i cant really bring myself to criticize because it is genuinely clearly rather heartfelt in a way which i too have felt and sympathize with: snipe though i may I still sympathize with the general platform and the desires behind it: for a better way of living. Further the general premise of the article is made into a rather useful request at the end, even if i still feel that the author failed to live up to it:

“ If only we could show more courage in defining what our project is about at a fundamental level...”

Well to the author i say this: if that project is independence please count me as, though a critic, an ally. But if it is nationalism then i would encourage you to see which spooks and phantasms still haunt you and to see which wheels turn in your head.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This time it’s different

Before I got ready for work on Monday morning, I scrolled quickly through Facebook to see if there was anything interesting. A short, matter-of-fact post from Nicola Sturgeon stated she’d be making a speech at Bute House later that day. My instincts told me this might be something big.

Ever since Scotland voted 62% to Remain in the EU referendum last year, but the UK as a whole voted to Leave, there has been a sense of calm before a storm. A nervous, invisible energy has coursed through Scottish politics. Since then, Theresa May has added insult to injury by going for a “hard Brexit” and wilfully ignoring the compromises suggested by the Scottish Government. The message seemed to be that Scotland should just shut up and accept its fate while the UK Government got on with wrecking the economy and endangering our rights, particularly those of EU citizens living here – and all of that against the clear will of the Scottish people. It’s the attitude of a colonial master, not a democratic leader.

Since 19th September 2014, I’ve felt a second referendum was inevitable, though I’d no idea how far in the future it might be. On the 24th June 2016, I knew it would be within the next five years. With the vote on triggering Article 50 taking place in the Commons and the SNP conference kicking off in a few days, I knew there was only one likely reason Nicola had called this sudden press conference.

Normally the north side of Charlotte Square is closed to traffic on these occasions, forcing the bus tours to divert. This always frustrates me because I want to see what’s going on. But on this occasion, the announcement had been made at such short notice that the relevant authorities hadn’t been able to make the arrangements. Which meant that an open-top green bus passed the front of Bute House twice that morning, with an excited wide-eyed tour guide staring at the assembled press and dropping hints to his bemused customers about what might be happening inside.

Monday was always going to be a bit of an unusual day for me. I’d recently heard the sad news that my granny had passed away and the funeral was to be held on Tuesday, in Dalmellington in Ayrshire. So I’d booked a room in Ayr for the Monday night. After work, I hurried home to get changed and pick up my bag before rushing back into town and catching a train to Glasgow. My mood was very strange and complex. I was sad and reflective about the purpose of my journey, but also excited about the day’s developments – and I’ve always liked trains.

On arrival at Queen Street station in Glasgow, my belly was rumbling and the train to Ayr was from Central Station. What I needed was somewhere that sold food, halfway between the two stations. It just so happens there is such a place, and where better to stop off for a drink and a bite that day than the Yes Bar? It was relatively quiet when I arrived, but while I was there a man walked in, threw his arms in the air and shouted “Yes!!!”. Helpful of him to remind everyone of the name of the bar. Maybe I’ll try it sometime – “Tron!!!” “Banshees!!!”.

Of course, it hasn’t all been one way. The Empire struck back, with Theresa May making a condescending statement about how Nicola’s speech was “deeply regrettable” and politics “isn’t a game”. The unionist press also had its pound of flesh, with a Telegraph columnist even calling for Sturgeon to be beheaded.

Then today, Theresa May announced that “now is not the time” for a referendum. This has been widely interpreted as an indication that she will attempt to block the Scottish Government’s intention to hold the referendum in late 2018/early 2019. Though the UK doesn’t have a written constitution, the convention is that the Scottish Government doesn’t have the authority to hold a legally binding referendum without something called a “Section 30” – permission from Westminster.

So the Scottish Parliament will hold a vote over whether to ask for a Section 30, win it with the combined votes of the Greens and the SNP, then apparently Westminster will say no. Do they think that will be the end of the matter? Do they think they can ignore the will of a nation, and drag it kicking and screaming into the quagmire? Scotland cannot be ruled without the consent of its people. Robert the Bruce understood that in 1320, and Theresa May will learn it pretty quickly soon.

The Tories seem oblivious to their own hypocrisy. They say another referendum will be too “divisive” and create too much “uncertainty” – this from the people who inflicted a horribly divisive referendum on the UK, the full consequences of which remain to be seen, in order to sort out an internal dispute in their own party. It’s breath-taking.

Of course, politics is divisive anyway. The “divisiveness” some complain about is a symptom of greater political engagement. So long as it’s respectful and non-violent, that’s no bad thing. Quite the opposite.

The attitude of Theresa May and the politics of Brexit mean that this debate is not just about the future of our country, it’s a fundamental appraisal of who we are. Are we a nation or a region? A sovereign people whose democratic will is respected, or a subjugated throng of schoolchildren who need to be told what’s best for them?

A modern, outgoing, progressive European nation? Or an insignificant backwater of an isolationist Little England?

2014 felt like a stark choice, but this time…

Well, this time feels different for many reasons. Different circumstances, different leaders… hopefully different outcome.

In 2012 the polls put support for independence at 28%, and in two years it rose to 45%. Now polls have support at 50%. Let’s not be complacent, but this is winnable. Especially if the Prime Minister continues to play into our hands.

In 1314, Robert the Bruce made a speech to his troops before the Battle of Bannockburn. Centuries later, Robert Burns adapted it to poetry in Scots Wha Hae.

So in the words of the two Roberts:

Welcome tae yer gory bed,

Or tae victorie.

0 notes