#billy budd 1962

Text

Oscar Nominee of All Time Tournament: Round 1, Group A

(info about nominees under the poll)

LEWIS STONE (1879-1953)

NOMINATIONS:

Lead- 1928/29 for The Patriot

--

TERENCE STAMP (1938-)

NOMINATIONS:

Supporting- 1962 for Billy Budd

#oscars#academy awards#oscar nominees#actors#film#lewis stone#the patriot 1928#terence stamp#billy budd 1962#billy budd#nominees group a#nominees group a polls

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

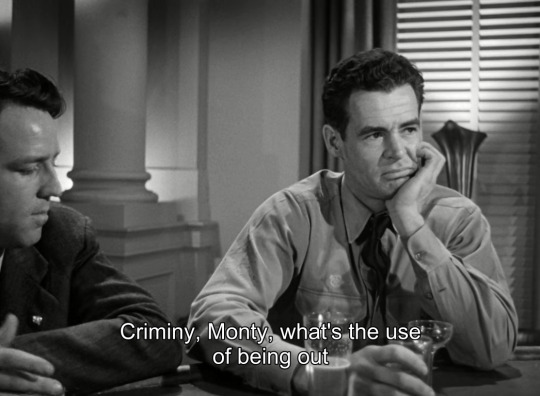

watching robert ryan be homophobic and gay again

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terence Stamp as Billy in Billy Budd (1962).

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Billy Budd, 1962, Peter Ustinov

Pretty sailor Billy clashes with sadistic Master in Arms Claggart. Powerful version of Melville's novel about innocence being sacrificed for duty. Stamp seductively naive on his debut, Ustinov sombre, nuanced, Ryan superb as a repressed monster.

1 note

·

View note

Text

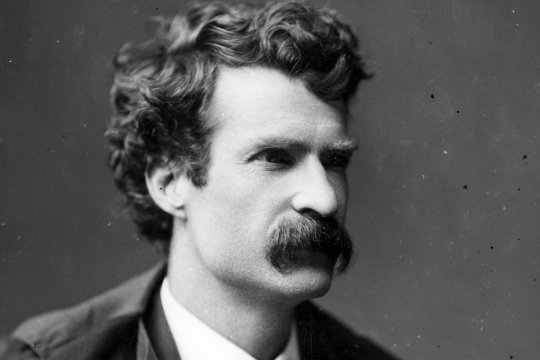

ROBERT RYAN.

Filmography

1940 The Ghost Breakers

1940 Mafia Queen

1940 Golden Gloves

1940 Northwest Mounted Police

1940 Texas Rangers reassemble

1943 Bomber

1943 The sky is the limit

1943 Behind the rising sun

1943 The Iron Major

1943 Catwalk for tomorrow

1943 Tender Companion

1944 Marine raiders

1947 Trail Street

1947 The Woman on the Beach

1947 Crossfire

1948 Berlin Express

1948 Return of the Bad Men

1948 The Green Haired Boy

1948 act of violence

1949 Caught

1949 commissioning

1949 I married a communist

1950 The Secret Fury

1950 Born to be bad

1951 Tough, Fast and Beautiful

1951 Best of the Bad

1951 Flying leather collars

1951 The racket

1951 On dangerous ground

1952 Clash at Night

1952 Watch out, my love

1952 Horizons West

1953 The Naked Spur

1953 City under the sea

1953 Hell

1954 Alaskan Seas

1954 About Mrs. Leslie

1954 His twelve men

1955 Bad Day at Black Rock

1955 Bamboo House

1955 Escape to Burma

1955 The Tall Men

1956 The Proud Marshal

1956 Back from Eternity

1957 Men at War

1958 Lonely Hearts

1958 God's Little Acre Ty Ty

1959 Outlaw Day

1959 Odds Against Tomorrow

1960 Ice Palace

1961 Canadians

1960 King of Kings

1962 The Longest Day

1962 Billy Budd

1964 World War I

1965 The Crooked Path

1965 Foul Play

1965 Battle of the Bulge

1966 The Professionals

1967 The Occupied Body

1967 The Dirty Dozen

1967 Gun Time

1967 West Custer

1968 One minute to pray, one second to die

1968 Anzio

1969 Wild Group

1969 Captain Nemo and the Underwater City

1971 Lawman

1971 The Love Machine

1972 ... and hope to die

1973 Lolly-Madonna XXX

1973 The Suit

1973 Executive Action

1973 The Iceman Comes.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Ryan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🦈 “The sea is calm you said. Peaceful. Calm above, but below a world of gliding monsters preying on their fellows. Murderers, all of them. Only the strongest teeth survive. And who's to tell me it's any different here on board, or yonder on dry land?"

Billy Budd (film) (1962)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Peter Ustinov (photos from 1962-1974. During these years he was nominated for 2 more Oscars, won one, won 2 more emmys, and nominated for a BAFTA for the Billy Budd screenplay. He also appeared in Billy Budd, Topkapi, and Hot Millions during this time.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

1861 Georges Méliès 1875 D.W. Griffith 1879 Victor Sjöström 1880 Tod Browning 1881 Cecil B. DeMille 1884 Robert Flaherty 1885 Allan Dwan / Sacha Guitry / G.W. Pabst / Erich von Stroheim 1886 Michael Curtiz / Henry King / John Cromwell 1887 Raoul Walsh 1888 F.W. Murnau 1889 Charles Chaplin / Jean Cocteau / Carl Theodor Dreyer / Victor Fleming / Abel Gance / James Whale 1890 Clarence Brown / Fritz Lang 1892 Ernst Lubitsch 1893 William Dieterle 1894 Frank Borzage / John Ford / Jean Renoir / King Vidor / Josef von Sternberg 1895 Buster Keaton 1896 Julien Duvivier / Howard Hawks / Leo McCarey / Dziga Vertov / William Wellman 1897 Frank Capra / Douglas Sirk 1898 René Clair / Sergei Eisenstein / Henry Hathaway / Mitchell Leisen / Kenji Mizoguchi / Preston Sturges 1899 George Cukor / Alfred Hitchcock 1900 Luis Buñuel / Mervyn LeRoy / Robert Siodmak 1901 Robert Bresson / Vittorio De Sica 1902 Emeric Pressburger / Max Ophüls / William Wyler 1903 Vincente Minnelli / Yasujiro Ozu 1904 Delmer Daves / Terence Fisher / George Stevens / Jacques Tourneur / Edgar G. Ulmer 1905 Mikio Naruse / Michael Powell / Otto Preminger / Jean Vigo 1906 Jacques Becker / Marcel Carné / John Huston / Anthony Mann / Carol Reed / Roberto Rossellini / Luchino Visconti / Billy Wilder 1907 Henri-Georges Clouzot / Joseph H. Lewis / Jacques Tati / Fred Zinnemann 1908 Tex Avery / Edward Dmytryk / Phil Karlson / David Lean / Manoel de Oliveira 1909 Elia Kazan / Joseph Losey / Joseph L. Mankiewicz 1910 John Sturges / Akira Kurosawa 1911 Jules Dassin / Nicholas Ray 1912 Michelangelo Antonioni / Samuel Fuller / Gene Kelly / Alexander Mackendrick / Don Siegel 1913 André de Toth / Mark Robson / Frank Tashlin 1914 Mario Bava / William Castle / Robert Wise 1915 Orson Welles 1916 Budd Boetticher / Richard Fleischer / George Sidney 1917 Maya Deren / Jean-Pierre Melville 1918 Robert Aldrich / Ingmar Bergman 1920 Federico Fellini / Eric Rohmer 1921 Luis García Berlanga / Miklós Jancsó / Chris Marker / Satyajit Ray 1922 Blake Edwards / Jonas Mekas / Pier Paolo Pasolini / Arthur Penn / Alain Resnais 1923 Ousmane Sembene / Seijun Suzuki 1924 Stanley Donen / Sidney Lumet 1925 Robert Altman / Claude Lanzmann / Sam Peckinpah / Maurice Pialat 1926 Roger Corman / Shohei Imamura / Jerry Lewis / Andrzej Wajda 1927 Kenneth Anger / Ken Russell 1928 Stanley Kubrick / Jacques Rivette / Nicolas Roeg / Agnès Varda / Andy Warhol 1929 Hal Ashby / John Cassavetes / Alejandro Jodorowsky / Sergio Leone 1930 Claude Chabrol / Clint Eastwood / John Frankenheimer / Kinji Fukasaku / Jean-Luc Godard / Frederick Wiseman 1931 Jacques Demy / Mike Nichols / Ermanno Olmi 1932 Milos Forman / Monte Hellman / Louis Malle / Nagisa Oshima / Carlos Saura / Andrei Tarkovsky / François Truffaut 1933 John Boorman / Stan Brakhage / Roman Polanski / Bob Rafelson / Jean-Marie Straub 1934 Sydney Pollack 1935 Woody Allen / Theo Angelopoulos 1936 Hollis Frampton / Danièle Huillet / Ken Loach 1937 Ridley Scott 1938 Paul Verhoeven 1939 Peter Bogdanovich / Francis Ford Coppola / William Friedkin / Glauber Rocha 1940 Dario Argento / Brian De Palma / Victor Erice / Terry Gilliam / Abbas Kiarostami / George A. Romero 1941 Bernardo Bertolucci / Stephen Frears / Patricio Guzmán / Krzysztof Kieslowski / Hayao Miyazaki / Raúl Ruiz / Bertrand Tavernier 1942 Peter Greenaway / Michael Haneke / Werner Herzog / Walter Hill / Martin Scorsese 1943 Roy Andersson / David Cronenberg / Mike Leigh / Terrence Malick / Michael Mann / Alan Rudolph 1944 Charles Burnett / Jonathan Demme / George Lucas / Peter Weir 1945 Terence Davies / Rainer Werner Fassbinder / George Miller / Wim Wenders 1946 Joe Dante / Claire Denis / David Lynch / Paul Schrader / Oliver Stone / John Woo 1947 Hou Hsiao-hsien / Takeshi Kitano / Rob Reiner / Steven Spielberg / Edward Yang 1948 John Carpenter / Philippe Garrel / Errol Morris 1949 Pedro Almodóvar 1950 Chantal Akerman / John Landis / John Sayles 1951 Kathryn Bigelow / Jean-Pierre Dardenne / Abel Ferrara / Aleksandr Sokurov / Robert Zemeckis / Zhang Yimou 1952 Jacques Audiard / Gus Van Sant 1953 Jim Jarmusch 1954 James Cameron / Jane Campion / Joel Coen / Luc Dardenne / Ang Lee / Michael Moore 1955 Olivier Assayas / Béla Tarr / Johnnie To 1956 Danny Boyle / Guy Maddin / Lars von Trier / Wong Kar-wai 1957 Ethan Coen / Aki Kaurismäki / Spike Lee / Mohsen Makhmalbaf / Tsai Ming-liang 1958 Tim Burton 1959 Nuri Bilge Ceylan / Pedro Costa / Sam Raimi 1960 Leos Carax / Atom Egoyan / Hong Sang-soo / Richard Linklater / Takashi Miike / Jafar Panahi 1961 Alfonso Cuarón / Todd Haynes / Peter Jackson / Alexander Payne / Abderrahmane Sissako / Michael Winterbottom 1962 David Fincher / Hirokazu Koreeda / Kenneth Lonergan 1963 Michel Gondry / Alejandro González Iñárritu / Park Chan-wook / Steven Soderbergh / Quentin Tarantino 1964 Guillermo del Toro / Kelly Reichardt / Andrey Zvyagintsev 1965 Jonathan Glazer 1966 Lucrecia Martel 1967 Denis Villeneuve 1969 Wes Anderson / Darren Aronofsky / Noah Baumbach / Bong Joon-ho / James Gray / Spike Jonze / Steve McQueen / Lynne Ramsay 1970 Paul Thomas Anderson / Jia Zhangke / Christopher Nolan / Apichatpong Weerasethakul 1971 Sofia Coppola / Carlos Reygadas Directors listed by key production country (Country of birth, if it differs, is listed in brackets) Argentina Lucrecia Martel Australia Jane Campion (New Zealand) / George Miller Austria Michael Haneke (Germany) Belgium Chantal Akerman / Jean-Pierre Dardenne & Luc Dardenne Brazil Glauber Rocha Canada David Cronenberg / Atom Egoyan (Egypt) / Guy Maddin / Denis Villeneuve China Jia Zhangke / Zhang Yimou Denmark Carl Theodor Dreyer / Lars von Trier Finland Aki Kaurismäki France Olivier Assayas / Jacques Audiard / Jacques Becker / Robert Bresson / Leos Carax / Marcel Carné / Claude Chabrol / René Clair / Henri-Georges Clouzot / Jean Cocteau / Jacques Demy / Claire Denis / Julien Duvivier / Abel Gance / Philippe Garrel / Jean-Luc Godard / Sacha Guitry (Russia) / Patricio Guzmán (Chile) / Claude Lanzmann / Louis Malle / Chris Marker / Georges Méliès / Jean-Pierre Melville / Max Ophüls (Germany) / Maurice Pialat / Roman Polanski / Jean Renoir / Alain Resnais / Jacques Rivette / Eric Rohmer / Raúl Ruiz (Chile) / Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet / Jacques Tati / Bertrand Tavernier / François Truffaut / Agnès Varda (Belgium) / Jean Vigo Germany / West Germany Rainer Werner Fassbinder / Werner Herzog / F.W. Murnau / G.W. Pabst (Austria-Hungary) / Wim Wenders Greece Theo Angelopoulos Hong Kong Wong Kar-wai (China) / Johnnie To / John Woo (China) Hungary Miklós Jancsó / Béla Tarr India Satyajit Ray Iran Abbas Kiarostami / Mohsen Makhmalbaf / Jafar Panahi Italy Michelangelo Antonioni / Dario Argento / Mario Bava / Bernardo Bertolucci / Vittorio De Sica / Federico Fellini / Sergio Leone / Ermanno Olmi / Pier Paolo Pasolini / Roberto Rossellini / Luchino Visconti Japan Kinji Fukasaku / Shohei Imamura / Takeshi Kitano / Hirokazu Koreeda / Akira Kurosawa / Takashi Miike / Hayao Miyazaki / Kenji Mizoguchi / Mikio Naruse / Nagisa Oshima / Yasujiro Ozu / Seijun Suzuki Mauritania Abderrahmane Sissako Mexico Luis Buñuel (Spain) / Alejandro Jodorowsky (Chile) / Carlos Reygadas New Zealand Peter Jackson Poland Krzysztof Kieslowski / Andrzej Wajda Portugal Pedro Costa / Manoel de Oliveira Russia / USSR Sergei Eisenstein (Latvia) / Aleksandr Sokurov / Andrei Tarkovsky / Dziga Vertov (Poland) / Andrey Zvyagintsev Senegal Ousmane Sembene South Korea Bong Joon-ho / Hong Sang-soo / Park Chan-wook Spain Pedro Almodóvar / Victor Erice / Luis García Berlanga / Carlos Saura Sweden Roy Andersson / Ingmar Bergman / Victor Sjöström Taiwan Hou Hsiao-hsien (China) / Tsai Ming-liang (Malaysia) / Edward Yang (China) Thailand Apichatpong Weerasethakul Turkey Nuri Bilge Ceylan UK John Boorman / Danny Boyle / Terence Davies / Terence Fisher / Stephen Frears / Jonathan Glazer / Peter Greenaway / David Lean / Mike Leigh / Ken Loach / Joseph Losey (USA) / Alexander Mackendrick (USA) / Steve McQueen / Michael Powell / Michael Powell (UK) & Emeric Pressburger (Hungary) / Lynne Ramsay / Carol Reed / Nicolas Roeg / Ken Russell / Michael Winterbottom USA (A-B) Robert Aldrich / Woody Allen / Robert Altman / Paul Thomas Anderson / Wes Anderson / Kenneth Anger / Darren Aronofsky / Hal Ashby / Tex Avery / Noah Baumbach / Kathryn Bigelow / Budd Boetticher / Peter Bogdanovich / Frank Borzage / Stan Brakhage / Clarence Brown / Tod Browning / Charles Burnett / Tim Burton USA (C-D) James Cameron (Canada) / Frank Capra (Italy) / John Carpenter / John Cassavetes / William Castle / Charles Chaplin (UK) / Joel Coen & Ethan Coen / Francis Ford Coppola / Sofia Coppola / Roger Corman / John Cromwell / Alfonso Cuarón (Mexico) / George Cukor / Michael Curtiz (Hungary) / Joe Dante / Jules Dassin / Delmer Daves / Brian De Palma / André de Toth (Hungary) / Guillermo del Toro (Mexico) / Cecil B. DeMille / Jonathan Demme / Maya Deren (Ukraine) / William Dieterle (Germany) / Edward Dmytryk (Canada) / Stanley Donen / Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly / Allan Dwan (Canada) USA (E-G) Clint Eastwood / Blake Edwards / Abel Ferrara / David Fincher / Robert Flaherty / Richard Fleischer / Victor Fleming / John Ford / Milos Forman (Czechoslovakia) / Hollis Frampton / John Frankenheimer / William Friedkin / Samuel Fuller / Terry Gilliam / Michel Gondry (France) / Alejandro González Iñárritu (Mexico) / D.W. Griffith / James Gray USA (H-L) Henry Hathaway / Howard Hawks / Todd Haynes / Monte Hellman / Walter Hill / Alfred Hitchcock (UK) / John Huston / Jim Jarmusch / Spike Jonze / Phil Karlson / Elia Kazan (Turkey) / Buster Keaton / Henry King / Stanley Kubrick / John Landis / Fritz Lang (Austria) / Ang Lee (Taiwan) / Spike Lee / Mitchell Leisen / Mervyn LeRoy / Jerry Lewis / Joseph H. Lewis / Richard Linklater / Kenneth Lonergan / Ernst Lubitsch (Germany) / George Lucas / Sidney Lumet / David Lynch USA (M-R) Terrence Malick / Joseph L. Mankiewicz / Anthony Mann / Michael Mann / Leo McCarey / Jonas Mekas (Lithuania) / Vincente Minnelli / Michael Moore / Errol Morris / Mike Nichols (Germany) / Christopher Nolan (UK) / Alexander Payne / Sam Peckinpah / Arthur Penn / Sydney Pollack / Otto Preminger (Austria-Hungary) / Sam Raimi / Bob Rafelson / Nicholas Ray / Kelly Reichardt / Rob Reiner / Mark Robson (Canada) / George A. Romero / Alan Rudolph USA (S-U) John Sayles / Paul Schrader / Martin Scorsese / Ridley Scott (UK) / George Sidney / Don Siegel / Robert Siodmak (Germany) / Douglas Sirk (Germany) / Steven Soderbergh / Steven Spielberg / George Stevens / Oliver Stone / John Sturges / Preston Sturges / Quentin Tarantino / Frank Tashlin / Jacques Tourneur (France) / Edgar G. Ulmer (Austria-Hungary) USA (V-Z) Gus Van Sant / Paul Verhoeven (Netherlands) / King Vidor / Josef von Sternberg (Austria) / Erich von Stroheim (Austria) / Raoul Walsh / Andy Warhol / Peter Weir (Australia) / Orson Welles / William Wellman / James Whale (UK) / Billy Wilder (Austria-Hungary) / Robert Wise / Frederick Wiseman / William Wyler (Germany) / Robert Zemeckis / Fred Zinnemann (Austria-HungaryJonas Mekas)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020: Year of Opera

So, in order to expand my cultural horizons (and do this because I’ve been wanting to do this), I’m going to be trying to get through some operas this year! I’ll definitely be listening to these, and I’m going to try and find staged versions if I can - because opera is a form of theatre and performance is an important part of it. This list is based off of The Guardian’s List of Top 50 Operas, but if there’s one that you don’t see on here and recommend, let me know!

Crossed out titles will be the ones I’ve already listened to/watched, and ones with asterisks (*) by them will be ones that I’ve listened to parts of, but need to listen to the whole thing.

1) L’Orfeo - Claudio Monteverdi (1607)

2) Dido and Aeneas* - Henry Purcell (1689)

3) Guilio Cesare (Julius Caesar) - George Frideric Handel (1724)

4) Serse (Xerxes) - Handel (1738)

5) Orfeo ed Euridice (Orpheus and Eurydice)* - Christoph Willibald Gluck (1762)

6) Idomeneo - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1781)

7) Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) - Mozart (1786)

8) Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute)* - Mozart (1791)

9) Il Barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville)* - Gioachino Rossini (1816)

10) Guillaume Tell (William Tell)* - Rossini (1829)

11) Norma - Vincenzo Bellini (1831)

12) L’Elisir d’Amore (The Exilir of Love) - Gaetano Donizetti (1832)

13) Lucia di Lammermoor - Donizetti (1835)

14) Rigoletto - Giuseppe Verdi (1851)

15) La Traviata - Verdi (1853)

16) Don Carlos/Don Carlo - Verdi (1867)

17) Falstaff* - Verdi (1893)

18) Pagliacci - Ruggero Leoncavallo (1892)

19) La Bohème - Giacomo Puccini (1896)

20) Tosca* - Puccini (1900)

21) Madama Butterfly - Puccini (1904)

22) Turandot* - Puccini (1926)

23) Fidelio - Ludwig van Beethoven (1805)

24) Der Freischütz - Carl Maria von Weber (1821)

25) Lohengrin* - Richard Wagner (1850)

26) Tristan und Isolde* - Wagner (1865)

27) Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg - Wagner (1868)

28) Der Ring des Nibelungen - Wagner (1876)

29) Die Lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow) - Franz Lehár (1905)

30) Salome* - Richard Strauss (1905)

31) Der Rosenkavalier* - Strauss (1911)

32) Les Troyens - Hector Berlioz (1863/1890)

33) Carmen* - Georges Bizet (1875)

34) Manon* - Jules Massenet (1884)

35) Pelléas et Mélisande - Claude Debussy (1902)

36) The Bartered Bride - Bedrich Smetana (1866)

37) Boris Godunov - Modest Mussorgsky (1874)

38) Eugene Onegin - Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1879)

39) The Queen of Spades - Tchaikovsky (1890)

40) Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk - Dmitri Shostakovich (1934)

41) War and Peace - Sergei Prokofiev (1944)

42) The Rake’s Progress - Igor Stravinsky (1951)

43) Jenufa - Leoš Janáček (1904)

44) Bluebeard’s Castle - Béla Bartók (1918)

45) Wozzeck - Alban Berg (1925)

46) Porgy and Bess - George Gershwin (1935)

47) Peter Grimes - Benjamin Britten (1945)

48) The Turn of the Screw* - Britten (1954)

49) King Priam - Michael Tippett (1962)

50) Le Grand Macabre - György Ligeti (1978)

Some Additional Operas not on that list that I want to listen to/finish listening to:

51) Armide - Jean Baptiste Lully (1686)

52) Proserpine (Proserpina) - Lully (1680)

53) Phaëton - Lully (1683)

54) Roland - Lully (1685)

55) Aida* - Verdi (1871)

56) Otello* - Verdi (1887)

57) Così fan tutte - Mozart (1790)

58) Parsifal - Wagner (1878)

59) Faust - Charles Gounod (1859)

60) Les contes d’Hoffmann* - Offenbach (1881)

61) Elektra - Strauss (1909)

62) Rusalka* - Antonin Dvorák (1901)

63) La clemenza di Tito* - Mozart (1791)

64) Lakmé* - Léo Dilibes (1883)

65) La sonnambula - Bellini (1831)

66) Die Fledermaus - Johann Strauss II (1874)

67) Roméo et Juliette* - Gounod (1867)

68) Andrea Chénier - Umberto Giodano (1896)

69) Semiramide - Rossini (1823)

70) Dialogues of the Carmelites - Francis Poulenc (1956)

71) Anna Bolena - Donizetti (1830)

72) Les Huguenots - Giacomo Meyerbeer (1836)

73) Peer Gynt* - Edvard Grieg (1876)

74) Ariadne auf Naxos - Richard Strauss (1912)

75) Billy Budd - Britten (1951)

76) HMS Pinafore - Arthur Sullivan (1878)

77) Béatrice et Bénédict* - Berlioz (1862)

78) Edgar - Puccini (1889)

79) Hippolyte et Aricie - Jean-Philippe Rameau (1733)

80) The Merry Wives of Windsor - Otto Nicolai (1849)

81) Alceste - Gluck (1767)

82) Amahl and the Night Visitors - Gian Carlo Menotti (1951)

83) King Arthur* - Purcell (1691)

84) The Nose - Shostakovich (1929)

85) Castor et Pollux - Rameau (1737)

86) The Tempest - Thomas Adès (2004)

87) Die tote Stadt - Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1920)

88) Alfonso und Estrella - Franz Schubert (1822)

89) L’étoile - Emmanuel Chabrier (1877)

90) The Fairy Queen - Purcell (1692)

91) Where the Wild Things Are - Oliver Knussen (1983)

92) The Nightingale - Igor Stravinsky (1914)

93) L’enfant et les sortilèges* - Maurice Ravel (1925)

94) Punch and Judy - Harrison Birtwistle (1968)

95) Death in Venice - Britten (1973)

96) We Come to the River - Hans Werner Henze (1984)

97) Einstein on the Beach - Philip Glass (1976)

98) Taverner - Peter Maxwell Davies (1972)

99) A Midsummer Night’s Dream - Britten (1960)

100) The Prodigal Son - Britten (1968)

#moving along!#these mozart operas were lovely#i liked così slightly more than the marriage of figaro#which probably makes me *controversial*#but i don't care hehehe#i still liked marriage of figaro though#that part where figaro finds his parents#i could not stop laughing#and i just love cherubino with all of my heart#(now it's time for some rusalka - and then some merry wives of windsor!)#i realize that i am terribly behind on notes but i will get to them eventually :)#year of opera 2020 update

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Term of Trial (1962)

#terence stamp#him doing this role the same year he did billy budd is very funny to me#term of trial#term of trial 1962#60s#60s film#mine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

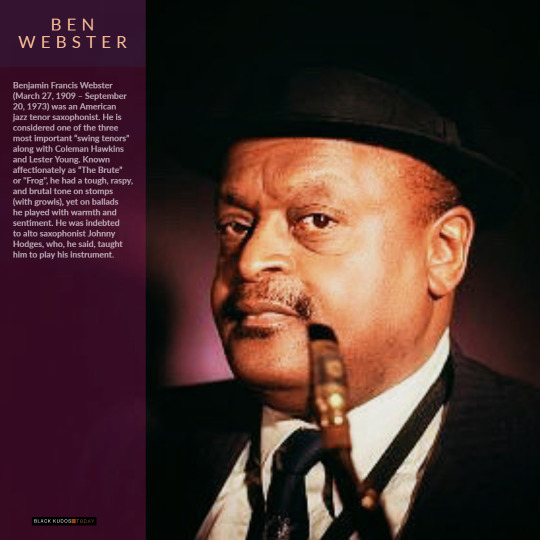

Ben Webster

Benjamin Francis Webster (March 27, 1909 – September 20, 1973) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. He is considered one of the three most important "swing tenors" along with Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young. Known affectionately as "The Brute" or "Frog", he had a tough, raspy, and brutal tone on stomps (with growls), yet on ballads he played with warmth and sentiment. He was indebted to alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, who, he said, taught him to play his instrument.

Early life and career

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, United States, he studied violin in elementary and taught himself piano with the help of his neighbor Pete Johnson, who taught him the blues. In 1927-1928 he played for silent movies in Kansas City and in Amarillo, Texas.

Once Budd Johnson showed him some basics on the saxophone, Webster began to focus on that instrument, playing in the Young Family Band (which at the time included Lester Young), although he did return to the piano from time to time, even recording on the instrument occasionally.

In his first biography (‘Ben Webster / In A mellow Tone’, Van Gennep/The Netherlands, 1992, published as ‘Ben Webster / His Life and Music’ with Berkeley Hills Books/USA in 2001), author Jeroen de Valk (assisted by Ben’s cousin Harley W. Robinson) traces back his ancestry to his great-great grandmother, a woman from Guinea who reportedly was brought to America as a slave in the early 19th century. Her son managed to escape from slavery. Ben’s father, who worked as a porter on Pullman trains, separated from his mother before his son was born. Ben was raised by his grand-aunt, Agnes Johnson, to whom he referred as his ‘grandmother’. His mother Mayme worked as a school teacher. He had to play the violin as a kid but hated the instrument, as other kids called him ‘sissy with the violin’. He had his first piano lessons by his second cousin, Joyce Cockrell. He changed to the tenor saxophone after hearing Frankie Trumbauer’s solo on the C-Melody saxophone in 'Singing The Blues', but soon Coleman Hawkins became a major influence. Webster was married for a couple of years in the early 40s to Eudora Williams. He never had a family of his own and lived with his mother and grand-aunt off and on until their passing in 1963.

Kansas City was a melting pot from which emerged some of the biggest names in 1930s jazz. Webster joined Bennie Moten's band in 1932, a grouping which also included Count Basie, Hot Lips and Walter Page. This era was recreated in Robert Altman's film Kansas City.

Webster spent time with quite a few orchestras in the 1930s, including Andy Kirk, the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in 1934, then Benny Carter, Willie Bryant, Cab Calloway, and the short-lived Teddy Wilson big band.

With Ellington

Ben Webster played with Duke Ellington's orchestra for the first time in 1935, and by 1940 was performing with it full-time as the band's first major tenor soloist. He credited Johnny Hodges, Ellington's alto soloist, as a major influence on his playing. During the next three years, he played on many recordings, including "Cotton Tail" and "All Too Soon"; his contributions (together with that of bassist Jimmy Blanton) were so important that Ellington's orchestra during that period is known as the Blanton–Webster band. Webster left the band in 1943 after an angry altercation during which he allegedly cut up one of Ellington's suits. Another version of Webster's leaving Ellington came from Clark Terry, a longtime Ellington player, who said that, in a dispute, Webster slapped Ellington, upon which the latter gave him two weeks notice.

After Ellington

After leaving Ellington in 1943, Webster worked on 52nd Street in New York City, where he recorded frequently as both a leader and a sideman. During this time he had short periods with Raymond Scott, John Kirby, Bill DeArango, and Sid Catlett, as well as with Jay McShann's band, which also featured blues shouter Jimmy Witherspoon. For a few months in 1948, he returned briefly to Ellington's orchestra.

In 1953, he recorded King of the Tenors with pianist Oscar Peterson, who would be an important collaborator with Webster throughout the decade in his recordings for the various labels of Norman Granz. Along with Peterson, trumpeter Harry 'Sweets' Edison and others, he was touring and recording with Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic package. In 1956, he recorded a classic set with pianist Art Tatum, supported by bassist Red Callender and drummer Bill Douglass. Coleman Hawkins Encounters Ben Webster with fellow tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins was recorded on December 16, 1957, along with Peterson, Herb Ellis (guitar), Ray Brown (bass), and Alvin Stoller (drums). The Hawkins and Webster recording is a jazz classic, the coming together of two giants of the tenor saxophone, who had first met back in Kansas City.

In the late 1950s, he formed a quintet with Gerry Mulligan and played frequently at a Los Angeles club called Renaissance. It was there that the Webster-Mulligan group backed up blues singer Jimmy Witherspoon on an album recorded live for Hi-Fi Jazz Records. That same year, 1959, the quintet, with pianist Jimmy Rowles, bassist Leroy Vinnegar, and drummer Mel Lewis, also recorded "Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster" for Verve Records (MG V-8343).

In Europe

Webster generally worked steadily, but in late 1964 he moved permanently to Europe, working with other American jazz musicians based there as well as local musicians. He played when he pleased during his last decade. He lived in London and several locations in Scandinavia for one year, followed by three years in Amsterdam and made his last home in Copenhagen in 1969. Webster appeared as a sax player in a low-rent cabaret club in the 1970 Danish blue film titled Quiet Days in Clichy. In 1971, Webster reunited with Duke Ellington and his orchestra for a couple of shows at the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen; he also recorded "live" in France with Earl Hines. He also recorded or performed with Buck Clayton, Bill Coleman and Teddy Wilson.

Webster suffered a cerebral bleed in Amsterdam in September 1973, following a performance at the Twee Spieghels in Leiden, and died on 20 September. His body was cremated in Copenhagen and his ashes were buried in the Assistens Cemetery in the Nørrebro section of the city.

Legacy

After Webster's death, Billy Moore Jr., together with the trustee of Webster's estate, created the Ben Webster Foundation. Since Webster's only legal heir, Harley Robinson of Los Angeles, gladly assigned his rights to the foundation, the Ben Webster Foundation was confirmed by the Queen of Denmark's Seal in 1976. In the Foundation's trust deed, one of the initial paragraphs reads: "to support the dissemination of jazz in Denmark". The trust is a beneficial foundation which channels Webster's annual royalties to musicians in both Denmark and the U.S. An annual Ben Webster Prize is awarded to a young outstanding musician. The prize is not large, but is considered highly prestigious. Over the years, several American musicians have visited Denmark with the help of the Foundation, and concerts, a few recordings, and other jazz-related events have been supported.

Webster's private collection of jazz recordings and memorabilia is archived in the jazz collections at the University Library of Southern Denmark, Odense.

Ben Webster used the same Saxophone from 1938 until his death in 1973. Ben left instructions that the horn was never to be played again. It is on display in the Jazz Institute at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ.

Ben Webster has a street named after him in southern Copenhagen, "Ben Websters Vej".

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Ben Webster among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.

Discography

As leader / co-leader

King of the Tenors [AKA The Consummate Artistry of Ben Webster] (Norgran, MGN-1001, 1953)

1953: An Exceptional Encounter [live] (The Jazz Factory, 1953) – with Modern Jazz Quartet

Music for Loving (Norgran MGN-1018, 1954) AKA Sophisticated Lady (Verve, 1956), and Music With Feeling (Norgran MGN-1039, 1955) – reissued as a 2-CD set: Ben Webster With Strings (Verve 527774, 1995; which also includes as a bonus: Harry Carney With Strings, Clef MGC-640, 1954)

The Art Tatum - Ben Webster Quartet (Verve, 1956 [1958]) – with Art Tatum

Soulville (Verve, 1957)

The Soul of Ben Webster (Verve, 1958)

Ben Webster and Associates (Verve, 1959)

Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster (Verve, 1959)

Ben Webster Meets Oscar Peterson (Verve, 1959)

Ben Webster at the Renaissance (Contemporary, 1960)

The Warm Moods (Reprise, 1961)

Wanted to Do One Together (Columbia, 1962) – with Harry Edison

Soulmates (Riverside, 1963) – with Joe Zawinul

See You at the Fair (Impulse!, 1964)

Stormy Weather (Black Lion, 1965) – recorded at The Jazzhus Montmartre, Copenhagen

Gone With The Wind (Black Lion, 1965) – recorded at The Jazzhus Montmartre, Copenhagen

Meets Bill Coleman (Black Lion, 1967)

Big Ben Time (Ben Webster in London 1967) (Philips, 1968)

Webster's Dictionary (Philips, 1970)

No Fool, No Fun [The Rehearsal Sessions, 1970 with The Danish Radio Jazz Orchestra] (Storyville Records STCD 8304, 1999)

Ben Webster Plays Ballads [recordings from Danish Radio 1967–1971] (Storyville SLP-4118, 1988)

Autumn Leaves (with Georges Arvanitas trio) (Futura Swing 05, 1972)

Gentle Ben (with Tete Montoliu Trio) (Ensayo, 1973)

My Man: Live at Montmartre 1973 (Steeplechase, 1973)

Ballads by Ben Webster (Verve, Recorded 1953-1959, released 1974, 2xLP)

As a sideman

With Count Basie

String Along with Basie (Roulette, 1960)

With Buddy Bregman

Swinging Kicks (Verve, 1957)

With Benny Carter

Jazz Giant (Contemporary, 1958)

BBB & Co. (Swingville, 1962) with Barney Bigard

With Harry Edison

Sweets (Clef, 1956)

Gee Baby, Ain't I Good to You (Verve, 1957)

With Duke Ellington

Never No Lament: The Blanton-Webster Band (RCA, 1940–1942 [rel. 2003])

With Dizzy Gillespie

The Complete RCA Victor Recordings (Bluebird, 1937–1949 [rel. 1995])

With Lionel Hampton

You Better Know It!!! (Impulse, 1965)

With Coleman Hawkins

Rainbow Mist (Delmark, 1944 [1992]) compilation of Apollo recordings

Coleman Hawkins Encounters Ben Webster (Verve, 1957)

Coleman Hawkins and Confrères (Verve, 1958)

With Woody Herman

Songs for Hip Lovers (Verve, 1957)

With Johnny Hodges

The Blues (Norgran, 1952–1954, [rel. 1955])

Blues-a-Plenty (Verve, 1958)

Not So Dukish (Verve, 1958)

With Richard "Groove" Holmes

"Groove" (Pacific Jazz, 1961) – with Les McCann

Tell It Like It Tis (Pacific Jazz, 1961 [rel. 1966])

With Illinois Jacquet

The Kid and the Brute (Clef, 1955)

With Barney Kessel

Let's Cook! (Contemporary, 1957 [rel. 1962])

With Mundell Lowe

Porgy & Bess (RCA Camden, 1958)

With Les McCann

Les McCann Sings (Pacific Jazz, 1961)

With Carmen McRae

Birds of a Feather (Decca, 1958)

With Oliver Nelson

More Blues and the Abstract Truth (Impulse!, 1964)

With Buddy Rich

The Wailing Buddy Rich (Norgran, 1955)

With Art Tatum

The Tatum Group Masterpieces, Volume Eight (Pablo, 1956)

With Clark Terry

The Happy Horns of Clark Terry (Impulse!, 1964)

With Joe Williams

At Newport '63 (RCA Victor, 1963)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

COVID-Diary, Week Ten

The prize for Scripture’s least celebrated rhetorical question should probably go to Zechariah ben Berechia ben Iddo, one of the three prophets who presided over the initial stages of Israel’s mid-sixth century BCE return to Zion after captivity in Babylon.

Looking out at the unfinishedness that characterized basically everything his eye could see—the so-far-only-partially-rebuilt walls of Jerusalem, the so-far-unsuccessful effort to rebuild the Temple and turn it into a functioning place of worship, the so-far-fruitless effort to place a scion of the House of David on the throne of Israel, and the so-far-failed effort to bring the descendants of the original exiles en masse back to the Jewish homeland and there to re-establish themselves, if not quite as a free people in its own place, then at least as a semi-autonomous ethnicity within the vast reaches of the Persian Empire—looking out at all that (and possibly remembering his older prophet-colleague’s promise that theirs was to be a day of “wholly new things”), the prophet acidulously asks his best question. Mi baz l’yom k’tanot? Are you really going to disrespect our moment in history as a nothing but a yom k’tanot, as “a day of small things” and negligible accomplishments?

It won’t matter in the long run, he promises, because the naysayers and scoffers will eventually all abandon their pessimism and rejoice in the nation’s future successes in all of the above undertakings. And, the prophet adds, the eyes of God are truly trained on the people at this specific juncture in their history, taking it all in and watching to see whether the people can summon up the will to do the right thing, to persevere, to keep at it…even despite the overwhelming nature of each single one of the tasks facing it. And who can say that small successes won’t turn into big ones? If I can summon up optimism in the face of the overwhelming nature of the tasks facing us all, the prophet almost says out loud, so why shouldn’t you also feel at least slightly hopeful? Is that really asking too much?

It’s one of my favorite passages in all the prophetic books, bringing together all my favorite COVID-era themes: guilt, irony, hope, resilience, and courage. And this truly is a day of small things, of small advances that feel unimportant in the larger picture. Last week, I wrote to you all about the dangers of magical thinking. This week, I’d like to write about a different danger facing us all: the danger of sinking into depression born of what we perceive to be realism, of doing precisely what the prophet forbade: being dismissive of small things because they aren’t big things, thus missing the opportunity to build on what already exists and, at least possibly, make small accomplishments into large ones.

The plague has taken a lot from each of us and some things from us all. Pleasures that once seemed have-able merely for the asking—heading out with a friend for a walk or a coffee somewhere, successfully finding an hour in an otherwise jammed week to work out at the gym, or to go for a swim, or to stop by the kids’ place to take the grandkids for an unexpected ice cream—even these simplest of life’s pleasures have all been taken from us. And yet these horrific weeks in which deaths in New York State have almost hit the 30,000 mark (of which almost 2,000 in Nassau County alone), these weeks that have taken so much from us and made us afraid to turn on the news at night lest we hear even more bad news, these weeks have also brought us small things—Zechariah’s k’tanot—to be grateful for.

There are lots of things I could mention. The curve has clearly flattened. At least some of the most dramatic efforts to deal with COVID—the transformation of the Javits Center into a US Army-run COVID hospital, for example, or the setting up of a field hospital for COVID patients in Central Park—have been abandoned as local hospitals have become more able to deal with all the COVID patients who require hospitalization. The transformation of society—something I once thought Americans, and particularly New Yorkers, would balk at taking seriously—feels almost completely successful: I went for my daily 2-mile walk yesterday and do not believe I passed a single person in the street who wasn’t wearing a protective mask. We’ve all learned how to deal with risks that must be taken—learning how to go shopping at 6 AM, for example, or how to order groceries without venturing into a grocery store—and the disruption feels, to me at least, minimal. Yes, these are all small things. Yes, well over 80,000 Americans have died in the course of the last few months. Yes, almost 1.4 million Americans have been confirmed as COVID-ill, which number is definitely far too low since, as of today, a mere 9,623,336 Americans have been tested for the virus…out of a population of over 331,000,000. Yes to all the above! But mi baz l’yom k’tanot? Are we really going to look past the successes because they are, in the end, our latter-day version of the prophet’s small things? It wasn’t a good idea in ancient times. And it’s not a good plan for today either.

I have lately sought solace in familiar places. You all know that I read a lot, that reading is my refuge from the world, my go-to place when I need to withdraw for a bit from the maelstrom and regroup internally and intellectually. It’s been that way with me my whole life, even when I was a boy and certainly when I was a teenager. And in this way too the boy became the father to the man—but it’s the direction of my reading that the age of COVID has altered. I’m usually all about new fiction. In my usual way I will share with my readers—possibly in this very space—an account of the books I have read in the past year and recommend as summer reading. And I’ve read some new authors this year that I’m eager to share with you all—American authors like Richard Morais or Madeline Miller, but also writers from more exotic climes like Cixin Liu, Yrsa Sigurdardottir, or Daniel Kehlmann. For the last few weeks, however, I’ve been finding solace and calm by returning to some familiar places and expanding those specific horizons slightly.

I somehow realized that I had read all of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novels but one, so I found and read a copy of his first book, Fanshawe, a work he was later on so ashamed of that he personally bought up all the unsold copies he could find and burned them in his own oven. That led me to notice that I had read all of Herman Melville’s novels (regular readers of these letters will know how great a fan I am) except for The Confidence Man (his last novel other than the unfinished Billy Budd), so I read that too. And now I have moved on to Mark Twain.

I am among those who think of Huckleberry Finn as the single greatest American novel. Like most people my age, I first read it when I was in high school. (I’m sure I had no real idea what it was about, which was true of any number of books assigned to us back in the day.) My idea was to re-read it, possibly after re-reading Tom Sawyer. But then I began to realize just how many holes there were in my effort to read all of Twain. It turns out there are “other” Tom Sawyer novels, books I don’t recall even hearing about and am certain I never read. So I decided to read them now…and then moved on to my current plan to read or re-read all of Twain. And it’s working, too: the more I read of Twain, the more comfortable I’ve been feeling, the more grounded, the more calm, the more ready to contextualize this whole corona-thing and see it in the context of the larger pageant of life in these United States over the last century and a half.

I began with The Prince and the Pauper, yet another of Twain’s books I somehow never actually read. Does reading the Classic Comics version count? Probably not. Nor should it matter that I remember watching the book’s three-part adaptation on Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color with my parents in 1962. Nor that I loved the 1977 movie version featuring Rex Harrison, Charlton Heston, Ernest Borgnine, George C. Scott, Oliver Reed, and Raquel Welch, which was for some reason distributed in the U.S. under the title, Crossed Swords. Twain didn’t write any of the above: he wrote a novel, published it in 1882 (just after the birth of one of my grandmothers and just before the other’s), and that is what I set myself to read.

On the surface, it’s a funny story about two eight-year-old boys, one the crown prince of England and the other an impoverished beggar living with a violent, angry father, and about how they manage (almost believably) to trade places and try on each other’s life for size. It’s well done, too—lots of surprise plot twists and a very engaging style that held my interest for as long as I was reading even despite the fact that I knew how it ended. But on a deeper level, it’s about something else entirely—about the nature of identity, about the question of whether you are how you perceive yourself or how others perceive you, about the fragility of individuality, and about the fluidity of the sense of self we all take for granted when we look in the mirror and, seeing ourselves looking back, take that experience as reflective of immutable reality.

And, for readers in the age of COVID, it’s also about finding a way to retain our sense of ourselves as unique beings when the entire world changes on a dime, when the palace vanishes and you find yourself suddenly on your own in a world you barely recognize, when you wake up one morning and—for reasons even you yourself can’t really fathom—nothing is as it was and your sole choice is between negotiating a brand new normal or being left behind as the universe moves forward. It’s a clever book about the nature of self-awareness, about the durable nature of personality, about the ability of the background to alter the foreground—but also about the limits that inhere in that ability when the people standing at the front of the stage insist on maintaining their allegiance to their own personalities even under the most peculiar and unforeseen circumstances.

If you’ve never read it, I recommend Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper as a good place to re-introduce yourself to one of our greatest authors. I plan to keep reading too, and I’ll report back to you as I make progress. When summer comes, I’ll share with you my recommendations for summer reading as I always do. But in the meantime, it’s just me and Sam Clemens on my back porch when the afternoon coffee is ready and I find the courage to turn my phone off for forty or fifty minutes and step into the world of a great man’s imagination. Within the context of appropriate social distancing, I invite you all to join me!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

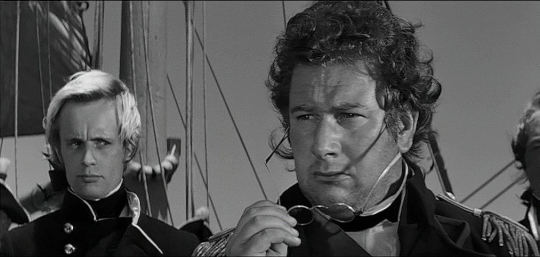

Billy Budd (1962)

Terrence Stamp playing the title character - not exactly General Zod but only his second movie and already he is the lead and nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The ‘supporting’ part don’t make no sense. But anyway...

Here’s the thing. I thought I was going to hate this movie. I thought it was going to be boring as hell and predictable. Instead I fell head over heels for Peter Ustinov, shook in my boots over Robert Ryan, and my heart broke for poor Billy Budd.

The movie takes place in war time and Robert Ryan, the sadistic seaman, (hehe) boards a merchant vessel and requisitions Billy Budd to come work on the military ship.

Billy is friendly and simple and soon makes friends with the crew who all warn him to steer clear of the Master at Arms, Robert Ryan.

The captain is played by Peter Ustinov who also directs. While Ustinov’s character knows he is in charge he doesn’t shirk from letting the Master at Arms do the dirty work.

Eventually, Robert Ryan’s character gets murdered, and Budd has to stand trial for the crime.

Billy Budd is a Melville story, which I have not had good luck with in the past. But I tell you - Ustinov’s presentation is compelling. He doesn’t hog the screen, he lets his actors act, and the dialog among the crew and the military leaders is fascinating.

Also, the cruelty and violence are subtle and mostly off screen but no less horrifying or brutal. I really felt the ship and the heat and the fear.

Billy Budd, where the law of the sea outweighs man’s conscience.

TCM is showing Billy Budd February 1 at 2:45 PST. If you are not home, record it. Or get it from Netflix, like I did. It’s available on DVD. Following Billy Budd TCM is showing another film featuring General Zod (Terrence Stamp), Far From the Madding Crowd. So you could have a double Terrence Stamp whammy.

For the past few years I have followed TCM and the 31 Days of Oscar line up. I try to select one film from each day, one I haven’t seen (or at least haven’t blogged about) before. Some of the films in this selection won Oscars and some did not but all were at least nominated.

#billy budd#terrence stamp#best supporting actor nominee#peter ustinov#robert ryan#31daysofoscar#tcm#tcmparty#herman melville

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Filmografía

1940

Los Ghost Breakers

Reina de la mafia

Guantes dorados

Policía Montada del Noroeste

Los Texas Rangers vuelven a montar

1943

Bombardero

El cielo es el límite

Detrás del sol naciente

El mayor de hierro

Pasarela para mañana

1944 Marine Raiders

1947

Trail Street

La mujer en la playa

Fuego cruzado

1948

Berlín Express

El regreso de los hombres malos

El chico de pelo verde

Acto de violencia

1949

Atrapado

La puesta en marcha

Me casé con un comunista

1950

La furia secreta

Nacido para ser malo

1951

Duro, Rápido y Hermoso

Lo mejor de los malos

Cuellos de cuero voladores

La raqueta

En terreno peligroso

1952

Choque por la noche

Cuidado, mi amor

Horizontes Oeste

1953

El espolón desnudo

Ciudad debajo del mar

1954

Mares de Alaska

Sobre la Sra. Leslie

Sus doce hombres

1955

Mal día en Black Rock

Casa de Bambú

Escape a Birmania

Los hombres altos

1956

Los orgullosos

De vuelta de la eternidad

1957

Hombres en guerra

1958

Corazones solitarios

El pequeño acre de Dios

1959

Día del forajido

Probabilidades contra el mañana

1960

Palacio de Hielo

1961

Los canadienses

Rey de Reyes

1962

El día más largo

Billy Budd

1964

Primera Guerra Mundial

1965

El camino torcido

El juego sucio

Batalla de la protuberancia

1966

The Professionals

1967

The Busy Body

The Dirty Dozen

Hour of the Gun

Custer of the West

1968

A Minute to Pray, a Second to Die

Anzio

1969

The Wild Bunch

Captain Nemo and the Underwater City

1971

Lawman

The Love Machine

1972

... and Hope to Die

1973

Lolly-Madonna XXX

The Outfit

Executive Action

The Iceman Cometh

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Ryan

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

1 note

·

View note

Text

I figured since I have already written it out I could post it here too. Here’s how Victor made his transition from being purely a stage performer to being a Hollywood actor:

Victor Charles Buono was studying acting at Villanova University, the only play he was in there was “Billy Budd” since his father was arrested and sentenced to twelve years in San Quentin for conspiracy to robbery that resultet in one death barely which forced 21-year-old Victor to return home to support his mother and his little brother and be the bread winner of the family.

He tried to break into Hollywood for a year and even though he was good the people there didn’t know in which roles to cast him and he didn’t get a part. But he was still performing at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego like he had already in his teens. In 1959 he was playing Falstaff in “Henry V, Part 1″, which should become his most celebrated stage role, after only ten days of rehearsal because the first cast actor suffered a back injury.

(This photo of him as Falstaff is actually from a 1962 production)

One night there was a talent scout from Warner Brothers present, Jerry Bloom, he took Victor back to Hollywood for a screentest and cast him as “Bongo Benny” in “77 Sunset Strip.

Jerry Bloom said about Victor in an 1961 article: “Buono has the goods. By the time he’s 30 he’ll be the most sought-after character actor in Hollywood. He’s a Laird Cregar-Sydney Greenstreet type -immense bulk but with an air of refinement.”

Victor started to have guest-appearances on a lot of western, adventure and crime TV shows, mostly as eccentric beatniks and all kinds of gangsters that usually don’t survive the end of the episode. And he had some uncredited roles in big movies.

Then in 1961 Robert Aldrich noticed Victor in the episode “Mr. Moon” in “The Untouchables” series where Victor played the titular character. And I completely understand why Aldrich took notice of him here and the newspapers as well for the first time. It’s a great episode unlike most of the other roles where he was just one of the gangsters this centered around him as an oily bad man with a brain and he delivered a strong performance.

Aldrich tried to convince Victor to audition for Baby Jane but Victor didn’t think the part of Edwin, that had been turned down by Peter Lawford before, was right for him, at all. But Craig Noel, the director at the Old Globe and supporter of him advised him to take this chance and there was also the prospect of meeting Bette Davis. And so Victor did audition for Baby Jane when he was in Hollywood anyway because he was shooting his first guest-appearance on “Perry Mason”. Obviously Victor got the part in the surprise hit shocker “What Ever Happened To Baby Jane?” (1962) that would earn him an Oscar nomination in 1963 at the age of 25.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Billy Budd

(1962) Directed by Peter Ustinov

Robert Krasker’s (The Third Man, Brief Encounter) excellent black-and-white cinematography, much of which was shot on the high seas, lends a first impression of your standard rousing naval adventure. It’s misleading.

The screenplay adapts Herman Melville’s novella, which should indicate to anyone even slightly familiar with the author’s body of work that this will be a devastating account of human failings and dilemmas.

Billy Budd (Terence Stamp, in the role that initiated his rise to international stardom) is a handsome young sailor—make that a slightly androgynous, stunning example of the Greek ideal of human beauty—whose simple-mindedness borders on mental deficiency. In the eyes of his shipmates (at least those below decks) Billy is just a wholesome country lad probably not ideally suited to life on the British man-o-war the H.M.S. Avenger.

At quarterdeck, the ship’s officers and Post Captain Vere (Peter Ustinov, surprisingly restrained) regard Billy as an admirable seaman who’s perhaps too good for his own good, and that’s all there is to it. However, for Master d’Arms John Claggart (Robert Ryan, as scary as he’s ever been), there are no good sailors. There’s just a crew of ne’er-do-wells who must be controlled by flogging and/or hanging.

Claggart is a sadist with an innate skill at manipulating his intellectual inferiors, and the British navy is a target-rich environment. When Churchill made that remark about rum, sodomy, and the lash, he must have had Claggart in mind.

In any case, Claggart can’t believe that Billy’s unassuming remarks and gentle answers to commands are anything other than a sly effort to mock his superiors. He knows how to break those types, but just imagine his baffled rage when he finally determines that Billy is the genuine article, or more infuriating, an innocent soul.

Claggart fairly vibrates with hatred, but a new type of sailor calls for a new type of manipulation, and he is cunning enough to meet the challenge. In some of the best scenes, the fascinating exchanges between these two recall, not accidentally, Christ being tempted in the desert.

The third act manages to be still more emotionally harrowing. I won’t spoil it, but suffice to say that a moral dilemma ensues. Captain Vere feels duty-bound to follow the law, although his officers sense an imperative to seek actual justice. This scenario might have been a facile ethics lesson (like an episode of “Star Trek”) but Peter Ustinov and DeWitt Bodeen’s brilliant screenplay emphasizes the madness of rigid legal systems.

It’s also clear that any one of these naval officers could argue either side of the debate. Sharpening their understanding merely sharpens their pain, and it might be that particular note of realism that lifts this tale out of the realm of melodrama.

6 notes

·

View notes