#battle of rabaul (1942)

Text

L'infanterie de marine de la marine impériale japonaise (Special Naval Landing Forces – SNLS) débarque en Nouvelle-Bretagne pour prendre Rabaul – Bataille de Rabaul (1942) – Campagne de Nouvelle-Guinée – Nouvelle-Guinée – Janvier 1942

#WWII#guerre du pacifique#pacific war#campagne de nouvelle-guinée#new guinea campaign#bataille de rabaul (1942)#battle of rabaul (1942)#marine impériale japonaise#imperial japanese navy#ijn#special naval landing forces#snls#rabaul#nouvelle-bretagne#new britain#nouvelle-guinée#new guinea#01/1942#1942

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The four Agano-class cruisers were light cruisers operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy. All were named after Japanese rivers. Larger than previous Japanese light cruisers, the Agano-class vessels were fast, but with little protection, and were under-gunned for their size (albeit with a powerful offensive torpedo armament, able to launch up to eight Type 93 "Long Lance" torpedoes in a salvo).

Completed on 31 October 1942, Agano participated in the battles for Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands during 1943. Agano was badly damaged in Rabaul harbor by aircraft from the aircraft carriers USS Saratoga and USS Princeton, and in a subsequent attack by aircraft from TF38 on 11 November, she received a torpedo hit. Ordered to home waters for repair, she was torpedoed and sunk north of Truk by the US submarine USS Skate (SS-305), on 16 February 1944.

[source: Wikipedia]

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

https://pacificeagles.net/the-guadalcanal-campaign/

The Guadalcanal Campaign

Kido Butai’s defeat at the Battle of Midway meant that American positions in the Central Pacific, including Hawaii, were now secure. US Navy Commander in Chief Admiral Ernest J. King now felt that the time was right to begin a counter-offensive, to take full advantage of the changing circumstances. He had long thought that the South Pacific was the key to blunting the Japanese offensive – if sufficient forces could be deployed to secure the lines of communication between the United States and Australia, then the area offered the perfect springboard for offensive operations against the key Japanese strongholds of Rabaul and New Guinea. This plan also had the advantage of keeping Allied forces in the Pacific active and engaged with the Japanese, rather than having them hold defensive positions until American industrial output allowed for a Central Pacific offensive to begin sometime in 1943.

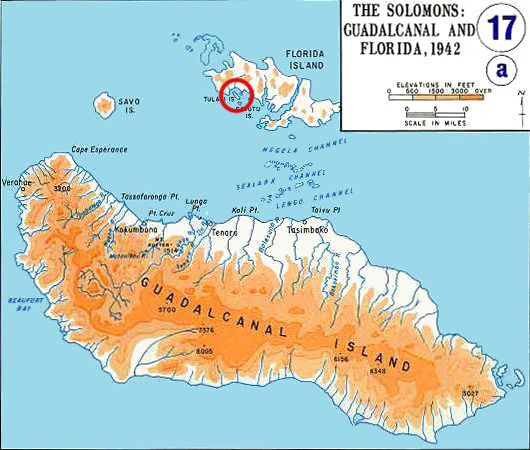

On June 24th King cabled Admiral Chester Nimitz to warn him operations were due to begin far sooner than anyone had previously thought possible – Nimitz was informed that he should begin planning for an offensive into the Solomon Islands, targeting Tulagi and “adjacent areas” with a start date of August 1st. That left just five weeks to prepare for what would be the first Allied offensive of the war, into an area that was badly lacking in adequate harbours and airfields. To work out the finer details Nimitz flew to San Francisco for a conference with King, but the XPBS-1 flying boat carrying the admiral crashed on landing and he was lucky to escape with his life.

Wreckage of Admiral Nimitz’s XPBS

Nimitz had already carved out part of his vast command territory, the South Pacific, and appointed V.Adm. Robert L. Ghormley, as Commander, South Pacific (COMSOPAC). He would have overall command of the operation, but he had only taken command of the theatre in May 1942. Now he found himself with just five weeks to prepare his meagre forces. The only major ground forces available to Ghormley were M.Gen Alexander A. Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division, but this unit was very green – most of the division was still on its way to New Zealand having left the US several weeks earlier. Several smaller units, including the Marine Raiders, the 1st Parachute Battalion, and the 3rd Defense Battalion with 90mm anti-aircraft guns, coastal defence guns and radar were attached the 1st Marine Division when the scope of their mission was expanded in mid-July.

More pressing was the lack of forward bases in the area. The major US forward base at Noumea had sufficient port facilities and a spacious airfield at Tontouta, but it lay almost 1,000 miles from Tulagi and could not offer adequate support to the marines. A fighter strip was under construction at Efate in the southern New Hebrides, itself 850 miles from the target area. Engineers raced to build another field at Turtle Bay on Espiritu Santo in the northern New Hebrides, which at 650 miles distant proved barely adequate as a base for B-17s and PBYs.

Land-based air support for the operation was under the command of RAdm John S. McCain. Elements of several Catalina squadrons from Patrol Wing 1 would provide reconnaissance, supported by the Flying Fortresses of the 11th Bomb Group. Tenders moved to Ndeni in the Santa Cruz islands to support the flying boats. For more direct support, the new Marine Air Group 23 was alerted for deployment to the Solomons once suitable airfields were captured. MAG-23 was only formed on 1st May and had just a handful of veteran pilots, the rest being rookies. VMF-223 and VMSB-232 formed the first echelon which boarded the escort carrier Long Island. VMF-224 and VMSB-242 were to follow when transportation was available. The Army’s 67th Pursuit Squadron was also based at Noumea, ready to move forward in support.

Heavy support for the landings would come in the form of VAdm Frank J. Fletcher’s Task Force 61, built around the carriers Enterprise, Saratoga and Wasp. Enterprise was by now a fixture of the Pacific War, having fought from the first day. Saratoga was returning to action following six months out due to torpedo damage. Wasp arrived in the South Pacific direct from the Panama Canal after an eventful period operating in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, where she twice delivered RAF Spitfires to the embattled island of Malta. All three carriers had an increased fighter compliment, with the standard VF squadron allotment of F4F Wildcats increased from 27 to 36 (although the smaller Wasp had just 30).

One invaluable service available to the invaders was Section C, Allied Intelligence Bureau, better known as the “Coastwatchers”. This was an organisation of mainly Australian and British civilians who lived in the Solomons and surrounding areas before the war, typically managing plantations or acting as colonial administrators. Many remained behind when the Japanese took over the islands, hiding in remote parts of the jungle and relying on the support of the native Solomon Islanders to remain hidden. Equipped with radios and commissioned into the naval services, the coastwatchers provided information about Japanese movements and sheltered Allied airmen who had to bail out over remote areas, amongst other roles. Key to the upcoming offensive would be Jack Read, based near Buka island off Bougainville, Paul Mason on southern Bougainville, and Martin Clemens on Guadalcanal.

Japanese opposition

Meanwhile, intelligence received from British coastwatchers in the Solomons revealed that in early July the Japanese had cleared several coconut plantations on the northern coast of Guadalcanal, across Savo Sound from Tulagi, and were beginning construction of an airfield. Heavy construction equipment was shipped in, and it became clear that the airfield would be complete by early August. The plan for Operation Watchtower was altered and the “adjacent positions” in King’s original operation order were explicitly defined as Guadalcanal and the Lunga Point airfield. The Japanese had only 4,000 troops on Guadalcanal, most of them engineers and Korean labourers. Across Savo Sound on Tulagi were another 1,500 troops including several Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) troops.

Aerial view of Lunga Point airfield under construction, July 1942

The principal Japanese air units in the region were based at Rabaul, well over 500 miles distant from Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The 5th Air Attack Force, administratively the 25th Air Flotilla, had several units of veteran fliers. The crack Tainan Kokutai had many veteran fighter pilots and was primarily equipped with Zero fighters. The 4th Kokutai, which had been badly handled by Lexington’s fighters on February 20, 1942, was equipped with G4M bombers. The 2nd Kokutai was another fighter unit, but they were equipped with shorter range Model 32 Zeros (later known as “Hamp”) that could not make the flight down to Guadalcanal and return. There were also elements of the Yokosuka and 14th Kokutai with H6K and H8K flying boats, some of which were based at Tulagi, as well as small units of floatplane Zero fighters. The major bases were Lakunai on the shores of Rabaul’s Simpson Harbour for the fighters, and Vunakanau further inland for the bombers. A small number of primitive emergency fields existed in the Solomons, primarily at Buka on the northern end of Bougainville and Kieta on the same island’s eastern coastline. No Imperial Japanese Army Air Force units were deployed in western New Guinea.

Final preparations

With only old, inaccurate charts of the target area available, Vandegrift had two of his intelligence offers carry out an aerial reconnaissance to fill in the gaps. Marines Col Merrill B. Twining and Maj William McKean flew to New Guinea and managed to procure an AAF B-17 for the effort. On July 17, 1942, they set out to look at “Ringbolt” (Tulagi) and “Cactus” (Guadalcanal). Tulagi was eventually found no less than 40 miles from where charts thought it was, but it appeared that the reef surrounding the island would be impenetrable to small landing craft and therefore amphibious tractors would be needed. Several floatplane Zeros were spotted trying to get airborne to catch the B-17, so it turned south for a look at Guadalcanal. Here it was revealed that there were no fortifications on the Guadalcanal coast and the beaches were clear of natural or manmade obstacles. The now-airborne Zeros got close enough to fire off a few bursts, with fire returned by the B-17’s gunners, before the Americans broke off and headed for Port Moresby.

Hand-drawn map of Lunga Point and the Japanese airfield, July 1942

Despite the frantic pace of preparations, it was clear that the original deadline of August 1st was impossible to meet. Instead Ghormley deferred D-Day until August 7th. The marines sailed from Wellington on July 22nd aboard transports commanded by RAdm Richmond K. Turner, King’s handpicked choice to lead the amphibious force. On the 26th, the amphibious squadron made rendezvous with Fletcher’s carriers south of Fiji and prepared for a practice landing on Koro the following day. During the dress rehearsal a bombardment of the landing beach was carried out by cruisers and bombing attacks were conducted by carrier planes, but the landing craft could not pass over coral heads and the practice landings themselves were cancelled. Vandegrift deemed the exercise a “complete bust”.

Following this failure, Admiral Fletcher convened a planning conference aboard his flagship, Saratoga. Admiral Ghormley was not present, because he had decided to remain at his HQ in Noumea. Fletcher, Turner, Vandegrift and their senior staff officers discussed the upcoming operation at length but disagreed over key details. There was acrimony over the amount of time TF-61 would remain in the area to provide air support as the marines got themselves established ashore. Turner estimated that it would take 4 or 5 days to fully unload the transports and wanted a full 5 days of cover, but Fletcher, worried about exposing his precious carriers to air and submarine attacks that were sure to come, was prepared to offer only 2 days – although he later increased this to 3. After that there would be no air support until MAG-23 could be flown in when the Lunga Point airfield was completed by marine engineers. With Ghormley unavailable to referee the dispute Fletcher got his way over the opposition of Turner and Vandegrift. With that, the commanders headed back to make their final preparations.

The Task Force now numbered 82 ships, the largest naval formation assembled up to that point in the Pacific War. Departing Fiji on the 28th, the force set a south easterly course in order to approach Guadalcanal and Tulagi from the south. Bombing attacks on Guadalcanal and Tulagi were carried out by the 11th Bomb Group – 9 B-17s struck on 31st July, flying from Efate to bomb the airfield at Lunga and disrupt construction works. A smaller raid the following day destroyed a pair of floatplane fighters, but an attack on the 4th was more difficult for the Americans. Three B-17s were intercepted by Zero floatplanes, one of which was damaged by the Flying Fortress’ gunners. The stricken fighter smashed into a B-17 and both aircraft went down. The next day another B-17 was lost in an attack on Tulagi.

On August 5th the ships turned north to begin the final run in, and Fletcher’s carriers broke off to take their supporting positions whilst the transports continued west of Guadalcanal before turning east into Savo Sound. There were no contacts with enemy ships, and radar screens remained blessedly clear of patrolling aircraft. As dawn broke on the 7th, D-Day, it was clear that the Americans had achieved complete surprise.

0 notes

Text

Unsinkable

the USS Tuna (SS-203) is an example of durability of a submarine built at Mare Island. The Japanese couldn’t sink her, friendly fire couldn’t, and nuclear weapons were not up to the task. In the end only the U.S. Navy could sink her when it was decided to scuttle her. USS Tuna was a United States Navy Tambor-class submarine launched at Mare Island on October 2 in 1940 as part of an arms build-up as the world grew ever more consumed by war. She served throughout the Pacific during World War II and earned seven battle stars. After the war, she was used as a test platform during the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb testing in 1946.

Tuna departed San Diego, California, on 19 May 1941 for Pearl Harbor and shakedown training. In one of those rare moments when adversity is twisted into opportunity the operations in Hawaiian waters revealed that the submarine's torpedo tubes were misaligned. This builder’s flaw took a positive turn when correcting the problem necessitated her returning to Mare Island for repairs. During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Tuna lay safely in drydock at Mare Island. Following repairs, she set out for Pearl Harbor an war patrols on 7 January 1942.

Tuna conducted 13 war patrols in the East China Sea, the Japanese home islands, the Aleutian Islands, the waters off the east coast of Vella LaVella; off New Ireland and Buka, and the Bismarck Archipelago, off Lyra Reef, on the northeast side of New Ireland. In mid-1943, as Tuna set out from Brisbane on her eighth patrol, a Royal Australian Air Force patrol bomber attacked her, dropping three bombs close aboard. The resultant damage necessitated 17 days of major repairs at Brisbane, delaying her departure for the eighth patrol. She then set off for the East Caroline Basin on the traffic lanes to Rabaul, and the Java Sea and Flores Sea before returning to Hunters Point Navy Yard in California, where she arrived on 6 April 1944 for a major overhaul. After refitting, she headed for the Palau Islands. Tuna roamed the sea lanes of the Japanese home islands, off Shikoku and Kyūshū. She then supported the invasion and liberation of the Philippines.

Tuna’s final war patrol began on 6 January as she left Saipan to take position off the west coast of Borneo. From 28 January to 30 January 1945, Tuna conducted a special mission, reconnoitering the northeast coast of Borneo. She did not attempt a landing due to enemy activity. From 2 March to 4 March, Tuna accomplished her second special mission of the patrol, landing personnel and 4400 pounds of stores near Labuk Bay.

Following the war Tuna was selected as a target vessel for the upcoming atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tuna was assigned a place among the target vessels anchored in the atoll. The first atomic bomb was detonated on 1 July 1946, and the second followed 24 days later. Receiving only superficial damage, following the Atomic bomb test Tuna was decommissioned on 11 December 1946, she was retained as a radiological laboratory unit and subjected to numerous radiological and structural studies while remaining at Mare Island. She was then towed from Mare Island for the submarine's "last patrol." On 24 September 1948, Tuna was sunk in 1,160 fathoms (6,960 ft) of water off the West Coast and struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 21 October 1948.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#submarine#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#Tuna#Unsinkable#atomic bomb#Bikini#Scuttle

0 notes

Text

Events 2.2 (after 1920)

1920 – The Tartu Peace Treaty is signed between Estonia and Russia.

1922 – Ulysses by James Joyce is published.

1922 – The uprising called the "pork mutiny" starts in the region between Kuolajärvi and Savukoski in Finland.

1925 – Serum run to Nome: Dog sleds reach Nome, Alaska with diphtheria serum, inspiring the Iditarod race.

1934 – The Export-Import Bank of the United States is incorporated.

1935 – Leonarde Keeler administers polygraph tests to two murder suspects, the first time polygraph evidence was admitted in U.S. courts.

1942 – The Osvald Group is responsible for the first, active event of anti-Nazi resistance in Norway, to protest the inauguration of Vidkun Quisling.

1943 – World War II: The Battle of Stalingrad comes to an end when Soviet troops accept the surrender of the last organized German troops in the city.

1954 – The Detroit Red Wings played in the first outdoor hockey game by any NHL team in an exhibition against the Marquette Branch Prison Pirates in Marquette, Michigan.

1959 – Nine experienced ski hikers in the northern Ural Mountains in the Soviet Union die under mysterious circumstances.

1966 – Pakistan suggests a six-point agenda with Kashmir after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

1971 – Idi Amin replaces President Milton Obote as leader of Uganda.

1971 – The international Ramsar Convention for the conservation and sustainable utilization of wetlands is signed in Ramsar, Mazandaran, Iran.

1980 – Reports surface that the FBI is targeting allegedly corrupt Congressmen in the Abscam operation.

1982 – Hama massacre: The government of Syria attacks the town of Hama.

1987 – After the 1986 People Power Revolution, the Philippines enacts a new constitution.

1989 – Soviet–Afghan War: The last Soviet armoured column leaves Kabul.

1990 – Apartheid: F. W. de Klerk announces the unbanning of the African National Congress and promises to release Nelson Mandela.

1998 – Cebu Pacific Flight 387 crashes into Mount Sumagaya in the Philippines, killing all 104 people on board.

2000 – First digital cinema projection in Europe (Paris) realized by Philippe Binant with the DLP CINEMA technology developed by Texas Instruments.

2004 – Swiss tennis player Roger Federer becomes the No. 1 ranked men's singles player, a position he will hold for a record 237 weeks.

2005 – The Government of Canada introduces the Civil Marriage Act. This legislation would become law on July 20, 2005, legalizing same-sex marriage.

2007 – Police officer Filippo Raciti is killed when a clash breaks out in the Sicily derby between Catania and Palermo, in the Serie A, the top flight of Italian football. This event led to major changes in stadium regulations in Italy.

2012 – The ferry MV Rabaul Queen sinks off the coast of Papua New Guinea near the Finschhafen District, with an estimated 146–165 dead.

2021 – The Burmese military establishes the State Administration Council, the military junta, after deposing the democratically elected government in the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état.

0 notes

Text

• No. 77 Squadron RAAF

Motto: "Swift to Destroy"

Squadron Code: AM (1942-)

No. 77 Squadron is a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) squadron headquartered at RAAF Base Williamtown, New South Wales. The squadron was formed at RAAF Station Pearce, Western Australia, in March 1942 and saw action in the South West Pacific theatre of World War II, operating Curtis P-40 Kittyhawks.

As the Japanese advanced in the South West Pacific during early 1942, the RAAF hurriedly established three fighter units—Nos. 75, 76 and 77 Squadrons—equipped with Curtiss P-40E Kittyhawks recently delivered from the United States. No. 77 Squadron was formed at RAAF Station Pearce, Western Australia, on March 16th, with a complement of three officers and 100 men. Temporarily commanded by Squadron Leader D. F. Forsyth, the unit was initially responsible for the defence of Perth. Squadron Leader Dick Cresswell assumed command on April 20th. The squadron transferred to Batchelor Airfield near Darwin, Northern Territory, in August, the first RAAF fighter unit to be stationed in the area. No. 77 Squadron moved to another of Darwin's satellite airfields, Livingstone, in September. No. 77 Squadron saw action defending Darwin from Japanese air raids and claimed its first aerial victory on November 23rd, 1942, when Cresswell destroyed a Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bomber. It was the first "kill" for an Australian squadron over the mainland, and the first night victory over Australia. As of December, the unit's strength was twenty-four Kittyhawks.

In February 1943, concurrent with No. 1 Wing and its three Supermarine Spitfire squadrons becoming operational in the Darwin area, No. 77 Squadron was transferred to Milne Bay in New Guinea. Along with Nos. 6, 75 and 100 Squadrons it came under the control of the newly formed No. 71 Wing, part of No. 9 Operational Group, the RAAF's main mobile formation in the South West Pacific Area. No. 77 Squadron registered its first daytime victory on April 11th, when a Kittyhawk shot down a Mitsubishi Zero taking part in a raid on Allied shipping. Three days later the Japanese attacked Milne Bay; the squadron claimed four bombers and a fighter, yet lost one Kittyhawk. By this time, Allied headquarters had finalised plans for a drive north to the Philippines involving heavy attacks on Rabaul and the occupation of territory in New Guinea, New Britain and the Solomon Islands. No. 77 Squadron began moving to Goodenough Island in May 1943, and was fully established and ready for operations June 15th. As Japanese fighter opposition was limited, the squadron took part in several ground-attack missions in New Britain, armed with incendiary and general-purpose bombs, a practice that had been employed by Kittyhawk units in the Middle East. Cresswell remained in command until Squadron Leader "Buster" Brown took over on August 20th. Japanese fighter strength in New Britain and New Guinea increased in September and October, and eight of No. 77 Squadron's Kittyhawks were briefly detached to Nadzab as escorts for the CAC Boomerangs of No. 4 Squadron.

In January 1944, No. 77 Squadron took part in the two largest raids mounted by the RAAF to that time, each involving over seventy aircraft attacking targets in New Britain. It was subsequently assigned to Los Negros in the Admiralty Islands, joining Nos. 76 and 79 Squadrons under No. 73 Wing. . 77 Squadron's ground party went ashore at Los Negros on March 6th, in the middle of a firefight with Japanese forces. Their primary duty was providing air cover for Allied shipping, though no Japanese aircraft were encountered; they also flew ground-attack missions in support of US troops on Manus Island. Following the capture of the Admiralties, which completed the isolation of Rabaul, No. 77 Squadron remained with No. 73 Wing on garrison duty at Los Negros from May to July 1944. Between the 13th of August and 14th of September 1944, the squadron transferred to Noemfoor in western New Guinea to join Nos. 76 and 82 Squadrons as part of No. 81 Wing under No. 10 Operational Group (later the Australian First Tactical Air Force), which had taken over the mobile role previously performed by No. 9 Group and was supporting the American landings along the north coast of New Guinea. Cresswell, now a wing commander, arrived for his second tour of duty as commanding officer. Operating P-40N Kittyhawks, No. 77 Squadron bombed Japanese positions on the Vogelkop Peninsula in October and on Halmahera in November. Cresswell handed over command in March 1945.

The squadron moved to Morotai on April 13th and conducted ground-attack sorties over the Dutch East Indies until June 30th, when it redeployed with No. 81 Wing to Labuan to support the 9th Australian Division in North Borneo until hostilities ended in August 1945. The squadron's tally of aerial victories during the war was seven aircraft destroyed and four "probables", for the loss of eighteen pilots killed. No. 77 Squadron began re-equipping with North American P-51 Mustangs at Labuan in September 1945. No. 77 Squadron was the last of the wing's three flying units to deploy to Japan, arriving at Bofu, a former kamikaze base, in March 1946. Occupation duties proved uneventful, the main operational task being surveillance patrols, but units maintained an intensive training regime and undertook combined exercises with other Allied forces.

No. 77 Squadron went on to serve in the Korean War. The Australian unit was specifically requested by General Douglas MacArthur, commander of UN forces. No. 77 Squadron did not encounter enemy aircraft in the opening phase of the war but often faced intense ground fire. . It suffered its first fatality on July 7th, 1950 when its deputy commander, Squadron Leader Graham Strout, was killed during a raid. He was also the first Australian, and the first non-American UN serviceman, to die in Korea. No. 77 Squadron served in the war until 1953. The squadron's final battle honor was given for the Malayan Emergency from 1960-1966. No. 77 Squadron was deployed also in 2001–02, supporting the war in Afghanistan, and deployed to the Middle East as part of the military intervention against ISIL in 2015–16. No. 77 Squadron is scheduled to convert to the new type of fighter in 2021.

#second world war#world war ii#world war 2#military history#wwii#history#british commonwealth#australian#australian history#australian airforce#royal air force#aviation

41 notes

·

View notes

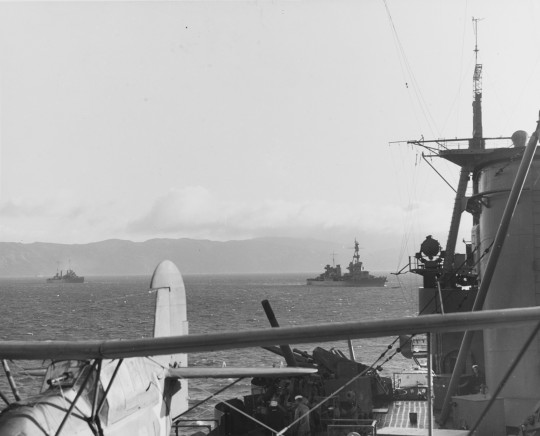

Photo

The invasion of Tulagi, on 3–4 May 1942, was part of Operation Mo, the Empire of Japan's strategy in the South Pacific and South West Pacific Area in 1942. The plan called for Imperial Japanese Navy troops to capture Tulagi and nearby islands in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. The occupation of Tulagi by the Japanese was intended to cover the flank of and provide reconnaissance support for Japanese forces that were advancing on Port Moresby in New Guinea, provide greater defensive depth for the major Japanese base at Rabaul, and serve as a base for Japanese forces to threaten and interdict the supply and communication routes between the United States and Australia and New Zealand.

Without the means to effectively resist the Japanese offensive in the Solomons, the British Resident Commissioner of the Solomon Islands protectorate and the few Australian troops assigned to defend Tulagi evacuated the island just before the Japanese forces arrived on 3 May. The next day, however, a U.S. aircraft carrier task force en route to resist the Japanese forces advancing on Port Moresby (later taking part in the Battle of the Coral Sea) struck the Japanese Tulagi landing force in an air attack, destroying or damaging several of the Japanese ships and aircraft involved in the landing operation. Nevertheless, the Japanese troops successfully occupied Tulagi and began the construction of a small naval base.

Over the next several months, the Japanese established a naval refueling, communications, and seaplane reconnaissance base on Tulagi and the nearby islets of Gavutu and Tanambogo, and in July 1942 began to build a large airfield on nearby Guadalcanal. The Japanese activities on Tulagi and Guadalcanal were observed by Allied reconnaissance aircraft, as well as by Australian coastwatcher personnel stationed in the area. Because these activities threatened the Allied supply and communication lines in the South Pacific, Allied forces* counter-attacked with landings of their own on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on 7 August 1942, initiating the critical Guadalcanal campaign and a series of combined arms battles between Allied and Japanese forces that, along with the New Guinea campaign, decided the course of the war in the South Pacific.

*It wasn’t ‘allied forces’, it was the fuckin’ Marines!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invasion_of_Tulagi_(May_1942)

0 notes

Photo

Akagi, the flagship of the Japanese carrier striking force which attacked Pearl Harbor, as well as Darwin, Rabaul, and Colombo, in April 1942 prior to the Battle of Midway https://wrhstol.com/2xITqIu

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

North-Eastern Area Command was one of several geographically based commands raised by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during World War II. It was formed in January 1942 and controlled units in central and northern Queensland, and Papua New Guinea. Headquartered at Townsville, Queensland, North-Eastern Area Command's responsibilities included air defence, aerial reconnaissance and protection of the sea lanes within its boundaries. Its flying units, equipped with fighters, reconnaissance bombers, dive bombers and transports, took part in the battles of Rabaul, Port Moresby and Milne Bay in 1942, and the landings at Hollandia and Aitape in 1944. The area command continued to operate after the war, but its assets and staffing were much reduced. Its responsibilities were subsumed in February 1954 by the RAAF's new functional commands: Home (operational), Training, and Maintenance Commands. The area headquarters was disbanded in December 1956 and re-formed as Headquarters RAAF Townsville.

0 notes

Photo

The Wikipedia article of the day for June 17, 2019 is North-Eastern Area Command.

North-Eastern Area Command was one of several geographically based commands raised by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during World War II. It was formed in January 1942 and controlled units in central and northern Queensland, and Papua New Guinea. Headquartered at Townsville, Queensland, North-Eastern Area Command's responsibilities included air defence, aerial reconnaissance and protection of the sea lanes within its boundaries. Its flying units, equipped with fighters, reconnaissance bombers, dive bombers and transports, took part in the battles of Rabaul, Port Moresby and Milne Bay in 1942, and the landings at Hollandia and Aitape in 1944. The area command continued to operate after the war, but its assets and staffing were much reduced. Its responsibilities were subsumed in February 1954 by the RAAF's new functional commands: Home (operational), Training, and Maintenance Commands. The area headquarters was disbanded in December 1956 and re-formed as Headquarters RAAF Townsville.

0 notes

Photo

https://pacificeagles.net/11-go-air-search-radar/

11-Go Air Search Radar

A Japanese scientific delegation under Cdr Yoji Ito was sent to Germany in February 1941. Although the professional relationship between the Japanese and the Germans was far less cordial than that of the Americans and British, the Germans showed enough evidence of the development of radar for Ito to be shocked. The capabilities of both of their erstwhile ally and the British were evident to Ito and his team and were amply demonstrated by two radar-assisted victories enjoyed by the British in the spring of 1941 – the Battle of Cape Matapan, during which Royal Navy ships sank three cruisers and two destroyers in a night action, and the destruction of the Bismarck which was shadowed by radar-equipped cruisers. Fearing that their advantage in night-combat skills would disappear in the face of Allied technological superiority, the Japanese Navy began a program to produce their own radar designs to close the gap.

Technical assistance for the design of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s first radar was provided by national broadcaster NHK’s Technical Research Lab and the electronics firm NEC. A prototype set operating on 4.2m wavelength was built relatively quickly, followed by a 3m wavelength set in September 1941. In tests this prototype detected a medium bomber at 97km and a flight of three at 145km, performance that was comparable with early-model Allied air-search radar. Three firms were contracted to make components for the production models, designated Mark 1 (for land-based) Model 1 or 11-Go – these are often misnamed as Type 11 in English sources. These entered service remarkably quickly – the first was installed at Katsuura Lighthouse in November 1941.

A handful of 11-Go were produced during the first months of 1942, with the first overseas unit deployed to Rabaul in March. Another pair were deployed to Guadalcanal when the new airfield there was constructed. These were captured by the US Marines when they landed on the island in August 1942, and in the absence of their own radar marines of the 3rd Defense Battalion attempted to put one of the 11-Go into service without much success. One was later shipped to the Naval Research Laboratory where it underwent significant testing. Later still it was used to help train American aviators in the new field of “electronic warfare” helping them to recognise the distinctive nature of Japanese radar sets on their detection and warning gear.

Other 11-Go were deployed to Japanese-held island throughout 1942. Two were sent to Kiska in the Aleutians, where American ‘ferret’ aircraft detected their emissions. Others were deployed to Wake Island to help fend off the infrequent attacks launched by long-range bombers operating from Midway, as well as the Japanese Mandates (the Caroline and Marshall Islands) and the Bonin Islands, including Iwo Jima. Dozens were deployed in China and Japan, where they were frequently detected by B-29 crews on their receiving gear. In total around 30 11-Go sets were produced in several variants.

0 notes

Text

Events 1.23 (after 1920)

1920 – The Netherlands refuses to surrender the exiled Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany to the Allies.

1937 – The trial of the anti-Soviet Trotskyist center sees seventeen mid-level Communists accused of sympathizing with Leon Trotsky and plotting to overthrow Joseph Stalin's regime.

1941 – Charles Lindbergh testifies before the U.S. Congress and recommends that the United States negotiate a neutrality pact with Adolf Hitler.

1942 – World War II: The Battle of Rabaul commences Japan's invasion of Australia's Territory of New Guinea.

1943 – World War II: Troops of the British Eighth Army capture Tripoli in Libya from the German–Italian Panzer Army.

1945 – World War II: German admiral Karl Dönitz launches Operation Hannibal.

1950 – The Knesset resolves that Jerusalem is the capital of Israel.

1957 – American inventor Walter Frederick Morrison sells the rights to his flying disc to the Wham-O toy company, which later renames it the "Frisbee".

1958 – After a general uprising and rioting in the streets, President Marcos Pérez Jiménez leaves Venezuela.

1960 – The bathyscaphe USS Trieste breaks a depth record by descending to 10,911 metres (35,797 ft) in the Pacific Ocean.

1963 – The Guinea-Bissau War of Independence officially begins when PAIGC guerrilla fighters attack the Portuguese Army stationed in Tite.

1964 – The 24th Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the use of poll taxes in national elections, is ratified.

1967 – Diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Ivory Coast are established.

1967 – Milton Keynes (England) is founded as a new town by Order in Council, with a planning brief to become a city of 250,000 people. Its initial designated area enclosed three existing towns and twenty-one villages. The area to be developed was largely farmland, with evidence of continuous settlement dating back to the Bronze Age.

1968 – USS Pueblo (AGER-2) is attacked and seized by the Korean People's Navy.

1982 – World Airways Flight 30H overshoots the runway at Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts, and crashes into Boston Harbor. Two people are presumed dead.

1986 – The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducts its first members: Little Richard, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Fats Domino, The Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley.

1987 – Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan sends a "letter of death" to Somali President Siad Barre, proposing the genocide of the Isaaq people.

1997 – Madeleine Albright becomes the first woman to serve as United States Secretary of State.

1998 – Netscape announces Mozilla, with the intention to release Communicator code as open source.

2001 – Five people attempt to set themselves on fire in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, an act that many people later claim is staged by the Chinese Communist Party to frame Falun Gong and thus escalate their persecution.

2002 – U.S. journalist Daniel Pearl is kidnapped in Karachi, Pakistan and subsequently murdered.

2003 – A very weak signal from Pioneer 10 is detected for the last time, but no usable data can be extracted.

2018 – A 7.9 Mw earthquake occurs in the Gulf of Alaska. It is tied as the sixth-largest earthquake ever recorded in the United States, but there are no reports of significant damage or fatalities.

2018 – A double car bombing in Benghazi, Libya, kills at least 33 people and wounds "dozens" of others. The victims include both military personnel and civilians, according to local officials.

2018 – The China–United States trade war begins when President Donald Trump places tariffs on Chinese solar panels and washing machines.

2022 – Mutinying Burkinabè soldiers led by Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba depose and detain President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré amid widespread anti-government protests.

0 notes

Text

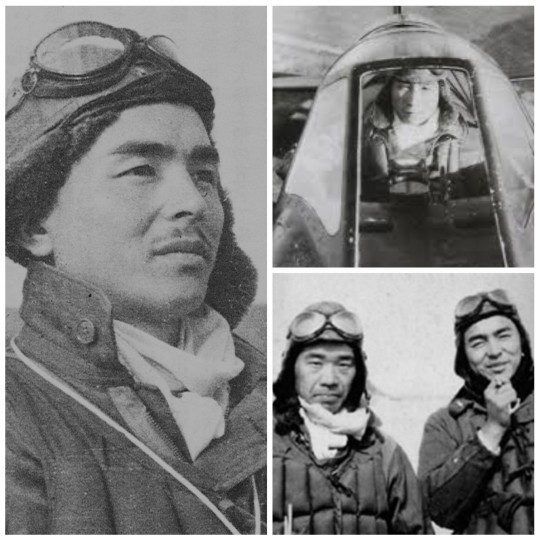

• Hiroyoshi Nishizawa (Japanese IJNAS Ace)

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa (西澤 広義) was an ace of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service as a Lieutenant Junior Grade during World War 2.

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa was born January 27th, 1920 in a mountain village in the Nagano Prefecture, the fifth son of Mikiji and Miyoshi Nishizawa. His father was the manager of a sake brewery. Hiroyoshi graduated from higher elementary school and then began to work in a textile factory. In June 1936, a poster caught his eye, an appeal for volunteers to join the Yokaren (flight reserve enlistee training program). Nishizawa applied and qualified as a student pilot in Class Otsu No. 7 of the Japanese Navy Air Force (JNAF). He completed his flight training course in March 1939, graduating 16th out of a class of 71. In October 1941, he was transferred to the Chitose Kōkūtai, with the rank of petty officer 1st class.

After the outbreak of war with the Allies, Nishizawa's squadron (chutai) from the Chitose Air Group, then flying the obsolete Mitsubishi A5M, moved to Vunakanau airfield on the newly taken island of New Britain. The squadron received its first Mitsubishi Zeros (A6M2, Model 21) the same week. On February 3rd, 1942, Nishizawa, still flying an obsolete A5M, claimed his first aerial kill of the war, a PBY Catalina. On February 10, Nishizawa's squadron was transferred to the newly formed 4th Air Group. As new Zeros became available, Nishizawa was assigned an A6M2 bearing the tail code F-108.

On 1 April 1942, Nishizawa's squadron was transferred to Lae, New Guinea and assigned to the Tainan Air Group. There he flew with aces Saburō Sakai and Toshio Ōta in a chutai (squadron) led by Junichi Sasai. Sakai described his friend Nishizawa as about "5-foot-8, 140 lb (64 kg) in weight, pale and gaunt, suffering constantly from malaria and tropical skin diseases". Nishizawa's squadron mates nicknamed him the "Devil," considered him a reserved, taciturn loner. Of his performance in the air, Sakai, himself one of Japan's leading aerial aces, wrote, "Never have I seen a man with a fighter plane do what Nishizawa would do with his Zero".

They often clashed with United States Army Air Forces and Royal Australian Air Force fighters operating from Port Moresby. Nishizawa's first confirmable solo kill, of a USAAF P-39 Airacobra, was on April 11th. He claimed six more kills in a 72-hour period from May 1st-3rd, making him a confirmed fighter ace. Nishizawa was a member of the famed "Cleanup Trio" with Saburō Sakai and Toshio Ōta. On May 17th, 1942, Lieutenant Commander Tadashi "Shosa" Nakajima led the Tainan Ku on a mission to Port Moresby, with Sakai and Nishizawa as his wingmen. As the Japanese formation re-formed for the return flight, Sakai signaled Nakajima, that he was going after an enemy aircraft and peeled off. Minutes later, Sakai was over Port Moresby again, to keep his rendezvous with Nishizawa and Ōta. The trio now performed aerobatics, three tight loops in close formation. After that, a jubilant Nishizawa indicated that he wanted to repeat the performance. Diving to 6,000 ft (1,800 m), the three Zeros did three more loops, still without any AA fire from the ground. They headed then back to Lae, arriving 20 minutes after the rest of the Kōkūtai.

In early August 1942, the air group moved to Rabaul, immediately operating against the US forces on Guadalcanal. In the first clash on August 7th, Nishizawa claimed six F4F Wildcats. On August 8th, 1942, Saburō Sakai, Nishizawa's closest friend, was severely wounded in combat with U.S. Navy Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers. Nishizawa noticed that Sakai was missing and went into a mad rage, he searched the area, both for signs of Sakai and for Americans to fight, presumably even if he had to ram them. Eventually, he cooled off and returned to Lakunai. Later, to everyone's amazement, the seriously wounded Sakai arrived. Nishizawa, Lieutenant Sasai and Toshio Ōta transported the obstinate but unconscious Sakai to the hospital. In frustrated concern, Nishizawa physically removed the waiting driver and personally drove Sakai, as quickly but as gently as possible, to the surgeon. Sakai was evacuated to Japan on August 12th. The extended conflict over Guadalcanal was costly for Nishizawa's air group (renamed the 251st in November) as American aircraft and tactics improved: Sasai was shot down and killed by Captain Marion E. Carl on August 26th, 1942, and Ōta was killed in October 1942.

In mid-November, the 251st was recalled to Toyohashi air base in Japan to replace its losses, with the ten surviving pilots all being made instructors, including Nishizawa. Nishizawa is believed to have had around 40 full or partial aerial victories by this time. Nishizawa, while staying in Japan, visited Saburō Sakai, who was still recuperating in the Yokosuka hospital. Nishizawa complained to Sakai of his new duty as an instructor. Nishizawa also ascribed the loss of most of their comrade pilots to the ever increasing material advantage of the Allied forces, the improved U.S. aircraft and tactics. Nishizawa could not wait to return to combat. "I want a fighter under my hands again," he said. "I simply have to get back into action. Staying home in Japan is killing me." Nishizawa publicly chafed at the months of inaction in Japan. He and the 251st returned to Rabaul in May 1943. In June 1943, Nishizawa's achievements were honored by a gift from the commander of the 11th Air Fleet, Vice Admiral Jin'ichi Kusaka. Nishizawa received a military sword inscribed "Buko Batsugun" ("For Conspicuous Military Valor"). He was then transferred to the 253rd Air Group on New Britain in September. In November, he was promoted to warrant officer and reassigned to training duties in Japan with the Oita Air Group.

In February 1944, he joined the 203rd Air Group, operating from the Kurile Islands, away from heavy action. In October, however, the 203rd was transferred to Luzon. Nishizawa and four others were detached to a smaller airfield on Cebu. On October 25th, 1944, Nishizawa led the fighter escort consisting of four A6M5s, flown by Nishizawa, Misao Sugawa, Shingo Honda and Ryoji Baba for the first major kamikaze attack of the war, targeting Vice Admiral Clifton Sprague's "Taffy 3" task force, which was protecting the landings in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The kamikaze volunteers, led by Lieutenant Yukio Seki, piloted five bomb-armed A6M2 Model 21 Zeros, each carrying a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb. They deliberately crashed their planes into U.S. warships in the first official kamikaze attack of the Tokkōtai suicide squadron "Shikishima". They were the first kamikazes to sink an enemy ship. The attack was very successful, as four of the five kamikazes struck their targets and inflicted heavy damage. While flying fighter escort to this kamikaze mission, Nishizawa recorded at minimum, his 86th and 87th victories, the final aerial victories of his career. Nishizawa reported the sortie's success to Commander Nakajima after returning to base. He then volunteered to take part in the next day's Tokkōtai kamikaze mission. His request was refused.

The following day, his own Zero having been destroyed, Nishizawa and other pilots of the 201st Kōkūtai boarded a Nakajima Ki-49 Donryu ("Helen") transport aircraft and left Mabalacat on Pampanga in the morning, to ferry replacement Zeros from Clark Field on Luzon. Over Calapan on Mindoro Island, the Ki-49 transport was attacked by two F6F Hellcats of VF-14 squadron from the fleet carrier USS Wasp and was shot down in flames. Nishizawa died as a passenger, probably the victim of Lt. j.g. Harold P. Newell, who was credited with a "Helen" northeast of Mindoro that morning.

Upon learning of Nishizawa's death, the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, honored Nishizawa with a mention in an all-units bulletin and posthumously promoted him to the rank of lieutenant junior-grade. Nishizawa was also given the posthumous name Bukai-in Kohan Giko Kyoshi, a Zen Buddhist phrase that translates: "In the ocean of the military, reflective of all distinguished pilots, an honored Buddhist person." Because of the confusion towards the end of the Pacific war, the bulletin's publication was delayed and funeral services were not held until December 2nd, 1947.

#second world war#world war 2#biography#ww2#japanese navy#imperial japan#japanese history#japan#military history#aviation#japanese air force#kamikaze#japanese zero

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

USS San Diego (CL-53), Light Cruiser, WWII by photolibrarian

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

History

Name:San Diego

Namesake:City of San Diego, California

Builder:Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation’s Fore River Shipyard, Quincy, Massachusetts

Laid down:27 March 1940

Launched:26 July 1941

Sponsored by:Grace Legler Benbough

Commissioned:10 January 1942

Decommissioned:4 November 1946

Reclassified:CLAA-53, 18 March 1949

Struck:1 March 1959

Identification:

Hull symbol:CL-53

Hull symbol:CLAA-53

Code letters:NCDF

ICS November.svgICS Charlie.svgICS Delta.svgICS Foxtrot.svg

Honors and

awards:Silver-service-star-3d.pngSilver-service-star-3d.pngSilver-service-star-3d.png 18 × battle stars

Fate:Sold for scrapping, December 1960

General characteristics (as built)[1][2]

Class and type:Atlanta-class light cruiser

Displacement:

6,718 long tons (6,826 t) (standard)

8,340 long tons (8,470 t) (max)

Length:541 ft 6 in (165.05 m) oa

Beam:53 ft (16 m)

Draft:

20 ft 6 in (6.25 m) (mean)

26 ft 6 in (8.08 m) (max)

Installed power:

4 × Steam boilers

75,000 shp (56,000 kW)

Propulsion:

2 × geared turbines

2 × screws

Speed:32.5 kn (37.4 mph; 60.2 km/h)

Complement:796 officers and enlisted

Armament:

16 × 5 in (127 mm)/38 caliber Mark 12 guns (8×2)

16 × 1.1 in (28 mm)/75 anti-aircraft guns (4×4)

8 × single 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannons

8 × 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes

6 × depth charge projectors

2 × depth charge tracks

Armor:

Belt: 1.1–3 3⁄4 in (28–95 mm)

Deck: 1 1⁄4 in (32 mm)

Turrets: 1 1⁄4 in (32 mm)

Conning Tower: 2 1⁄2 in (64 mm)

General characteristics (1945)[1][2]

Armament:

16 × 5 in (127 mm)/38 caliber Mark 12 guns (8×2)

4 × quad 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors anti-aircraft guns

13 × 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannons

8 × 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes

6 × depth charge projectors

2 × depth charge tracks

Service record

Part of:Fast Carrier Task Force

Operations:

Solomon Islands campaign

Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign

Mariana and Palau Islands campaign

Volcano and Ryukyu Islands campaign

Awards:18 battle stars

The second USS San Diego (CL-53) was an Atlanta-class light cruiser of the United States Navy, commissioned just after the US entry into World War II, and active throughout the Pacific theater. Armed with 16 5 in (127 mm)/38 cal DP anti-aircraft guns and 16 Bofors 40 mm AA guns, the Atlanta-class cruisers had one of the heaviest anti-aircraft broadsides of any warship of World War II.

San Diego was one of the most decorated US ships of World War II, being awarded 18 battle stars, and was the first major Allied warship to enter Tokyo Bay[3] after the surrender of Japan. Decommissioned in 1946, the ship was sold for scrapping in December 1960.

Construction

Launching of USS San Diego, 26 July 1941

San Diego was laid down on 27 March 1940 by Bethlehem Steel in Quincy, Massachusetts, sponsored by Grace Legler Benbough (wife of Percy J. Benbough, then-mayor of San Diego), launched on 26 July 1941, and acquired by the Navy and commissioned on 10 January 1942, Captain Benjamin F. Perry in command.[3]

Service history

1942–1943

After shakedown training in Chesapeake Bay, San Diego sailed via the Panama Canal to the west coast, arriving at her namesake city on 16 May 1942. Escorting Saratoga at best speed, San Diego barely missed the Battle of Midway. On 15 June, she began escort duty for Hornet in operations in the South Pacific. Early in August, she supported the first American offensive of the war, the invasion of the Solomons at Guadalcanal. With powerful air and naval forces, the Japanese fiercely contested the American thrust and inflicted heavy damage; San Diego witnessed the sinking of Wasp on 15 September and of Hornet on 26 October.[3]

San Diego gave antiaircraft protection for Enterprise as part of the decisive three-day Naval Battle of Guadalcanal from 12–15 November 1942. After several months of service in the dangerous waters surrounding the Solomon Islands, San Diego sailed via Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides, to Auckland New Zealand, for replenishment.[3]

At Noumea, New Caledonia, the light cruiser joined Saratoga, the only American carrier available in the South Pacific, and HMS Victorious in support of the invasion of Munda, New Georgia, and of Bougainville. On 5 November and 11 November 1943, she joined Saratoga and Princeton in highly successful raids against Rabaul. San Diego served as part of Operation Galvanic, the capture of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. She escorted Lexington, damaged by a torpedo, to Pearl Harbor for repairs on 9 December. San Diego continued on to San Francisco for installation of modern radar equipment, a Combat Information Center and 40 mm antiaircraft guns to replace her obsolete 1.1 in (27 mm) batteries.[3]

1944

She joined Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Task Force at Pearl Harbor in January 1944 and served as an important part of that mighty force for the remainder of the war. Her rapid-fire guns protected the carriers against aerial attack. San Diego participated in "Operation Flintlock", the capture of Majuro and Kwajalein, and "Catchpole", the invasion of Eniwetok, in the Marshall Islands from 31 January to 4 March. During this period, Task Force 58 (TF 58) delivered a devastating attack against Truk, the Japanese naval base known as the "Gibraltar of the Pacific."[3]

San Diego steamed back to San Francisco for more additions to her radar and then rejoined the carrier force at Majuro in time to join in raids against Wake and Marcus Islands in June. She was part of the carrier force covering the invasion of Saipan, participated in strikes against the Bonin Islands, and shared in the victory of the First Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June. After a brief replenishment stop at Eniwetok, San Diego and her carriers supported the invasion of Guam and Tinian, struck at Palau, and conducted the first carrier raids against the Philippines. On 6 and 8 August, she stood by as the carriers gave close air support to Marines landing on Peleliu, Palau Islands.[3]

On 21 September, the Task Force struck at the Manila Bay area. After replenishing at Saipan and Ulithi, she sailed with TF 38 in its first strike against Okinawa. From 12–15 October, the carriers pounded the airfields of Formosa while San Diego’s guns shot down two of the nine Japanese attackers in her sector and drove the others away; however, some enemy planes got through and damaged Houston and Canberra. San Diego helped escort the two crippled cruisers out of danger to Ulithi. After rejoining the fast carrier force, she successfully rode out the typhoon of 17–18 December, despite heavy rolling of the ship.[3]

1945

In January 1945, TF 38 entered the South China Sea for attacks against Formosa, Luzon, Indochina, and southern China. The force struck Okinawa before returning to Ulithi for replenishment.[3]

San Diego next participated in carrier operations against the home islands of Japan, the first since the Doolittle Raid of 1942. The carrier force finished the month of February with strikes against Iwo Jima.[3]

On 1 March, San Diego and other cruisers were detached from the carrier force to bombard Okino Daijo Island in support of the landings on Okinawa. After another visit to Ulithi, she joined in carrier strikes against Kyūshū, again shooting down or driving away enemy planes attacking the carriers. On the night of 27–28 March, San Diego participated in the shelling of Minami Daito Jima; on 11 April, and again on 16 April, her guns shot down two attackers. She helped furnish anti-aircraft protection for ships damaged by suicide attacks and escorted them to safety. After a stop at Ulithi, she continued as part of the carrier force supporting the invasion of Okinawa, until she entered an advanced base drydock at Guiuan, Samar Island, Philippines, for repairs and maintenance.[3]

San Diego arrives at Yokosuka Naval Base, 30 August 1945

She then served once more with the carrier force operating off the coast of Japan from 10 July until hostilities ceased. On 27 August, San Diego was the first major Allied warship to enter Tokyo Bay since the beginning of the war, and she helped in the occupation of the Yokosuka Naval Base and the surrender of the Japanese battleship Nagato. After having steamed over 300,000 mi (480,000 km) in the Pacific, she returned to San Francisco on 14 September 1945. San Diego gave further service as part of "Operation Magic Carpet" in bringing American troops home.[3]

Decommissioning and sale

San Diego was decommissioned and placed in the Pacific Reserve Fleet on 4 November 1946, berthed at Bremerton, Washington. She was redesignated CLAA-53 on 18 March 1949. 10 years later, she was struck from the Naval Vessel Register, on 1 March 1959.[3] Sold in December 1960 to Todd Shipyards, Seattle, WA.

Awards

USS San Diego (CL 53) memorial, April 2012.

USS San Diego (CL-53) received 18 Battle Stars[4][5] for service in World War II, placing her among the Most decorated US ships of World War II.

Following is a list of the campaigns participated in:[6]

Guadalcanal Capture

Buin-Faisi-Tonolai Raid

Santa Cruz Islands

Guadalcanal (Third Savo)

Rennel Island Jan.

New Georgia-Rendova-Vaugunu

Buka-Bonins Strike

Gilbert Islands Occupation

Kwajelein-Wotje

Truk Attack, February 16–17, 1944

Saipan-Pagan Attacks

Southern Palau Islands

Southern Palau Islands, Philippine Islands Assaults

Okinawa Attack

Formosa Attacks

China Coast Attacks

Iwo Jima, Feb. 15 To March 16, 1945

Okinawa Assault And Occupation March, 17 To June 11, 1945

Philippine Liberation

#reconditioning #batteries car battery, #battery, rechargeable aa batteries, rechargeable batteries, battery charger, car batteries, nimh battery, battery doctor, battery reconditioning, battery repair, battery desulfator

@BatteryReconditioningNew Home

http://bit.ly/2I9sVzc

The post USS San Diego (CL-53), Light Cruiser, WWII by photolibrarian appeared first on Battery Reconditioning.

from Battery Reconditioning http://batteryreconditioning.onlinestorewebpro.com/uss-san-diego-cl-53-light-cruiser-wwii-by-photolibrarian/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=uss-san-diego-cl-53-light-cruiser-wwii-by-photolibrarian

0 notes

Photo

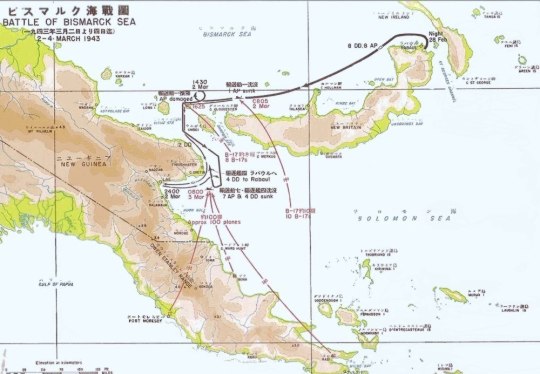

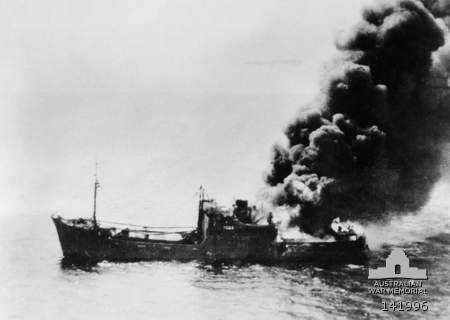

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea (2–4 March 1943) took place in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) during World War II when aircraft of the U.S. Fifth Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) attacked a Japanese convoy carrying troops to Lae, New Guinea. Most of the Japanese task force was destroyed, and Japanese troop losses were heavy.

The Japanese convoy was a result of a Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decision in December 1942 to reinforce their position in the South West Pacific. A plan was devised to move some 6,900 troops from Rabaul directly to Lae. The plan was understood to be risky, because Allied air power in the area was strong, but it was decided to proceed because otherwise the troops would have to be landed a considerable distance away and march through inhospitable swamp, mountain and jungle terrain without roads before reaching their destination. On 28 February 1943, the convoy – comprising eight destroyers and eight troop transports with an escort of approximately 100 fighter aircraft – set out from Simpson Harbour in Rabaul.

The Allies had detected preparations for the convoy, and naval codebreakers in Melbourne (FRUMEL) and Washington, D.C., had decrypted and translated messages indicating the convoy's intended destination and date of arrival. The Allied Air Forces had developed new techniques they hoped would improve the chances of successful air attack on ships. They detected and shadowed the convoy, which came under sustained air attack on 2–3 March 1943. Follow-up attacks by PT boats and aircraft were made on 4 March. All eight transports and four of the escorting destroyers were sunk. Of 6,900 troops who were badly needed in New Guinea, only about 1,200 made it to Lae. Another 2,700 were rescued by destroyers and submarines and returned to Rabaul. The Japanese made no further attempts to reinforce Lae by ship, greatly hindering their ultimately unsuccessful efforts to stop Allied offensives in New Guinea.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Bismarck_Sea

0 notes

Text

North-Eastern Area Command

North-Eastern Area Command.

North-Eastern Area Command was one of several geographically based commands raised by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during World War II. It was formed in January 1942 and controlled units in central and northern Queensland, and Papua New Guinea. Headquartered at Townsville, Queensland, North-Eastern Area Command's responsibilities included air defence, aerial reconnaissance and protection of the sea lanes within its boundaries. Its flying units, equipped with fighters, reconnaissance bombers, dive bombers and transports, took part in the battles of Rabaul, Port Moresby and Milne Bay in 1942, and the landings at Hollandia and Aitape in 1944. The area command continued to operate after the war, but its assets and staffing were much reduced. Its responsibilities were subsumed in February 1954 by the RAAF's new functional commands: Home (operational), Training, and Maintenance Commands. The area headquarters was disbanded in December 1956 and re-formed as Headquarters RAAF Townsville.

via Blogger http://bit.ly/2WH7Cc8

0 notes