#at san quentin

Text

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Live performance of "A Boy Named Sue," written by Shel Silverstein, at San Quentin State Prison in San Quentin, California on February 24, 1969. Track #8 on At San Quentin (1969).

#isaac.txt#johnny cash#country music#mp3#outlaw country#country#a boy named sue#at san quentin#san quentin state prison#discog

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

And he said, "Son, this world is rough

And if a man's gonna make it, he's gotta be tough

And I knew I wouldn't be there to help you along

So I give you that name and I said goodbye

I knew you'd have to get tough or die

And it's that name that helped to make you strong"

Yeah

He said, "Now you just fought one hell of a fight

And I know you hate me, and you got the right

To kill me now, and I wouldn't blame you if you do

But you ought to thank me, before I die

For the gravel in your guts and the spit in your eye

Because I'm the son-of-a-bitch that named you Sue"

✯ A Boy Named Sue, Johnny Cash

1 note

·

View note

Text

for context, literally the last thing he was talking about to the inmates here before asking for some water was how ridiculous it was that he had to pay a fine and spend a night in jail once for picking flowers. (johnny cash at san quentin)

58 notes

·

View notes

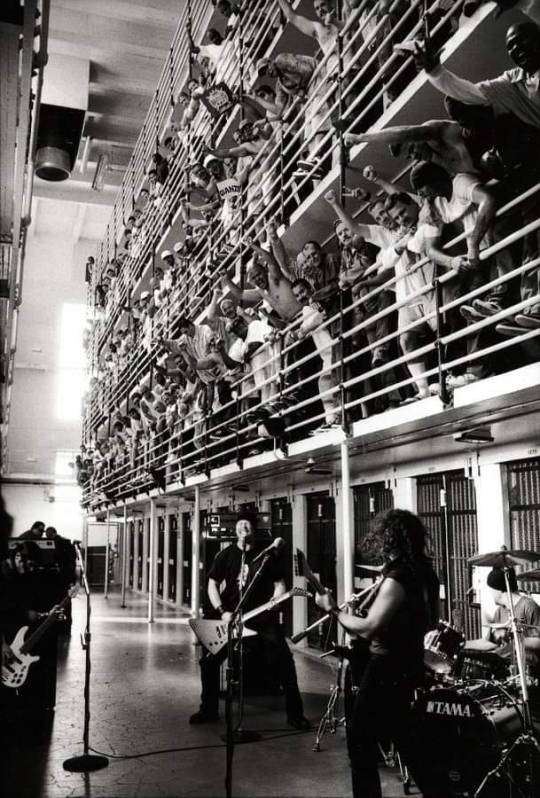

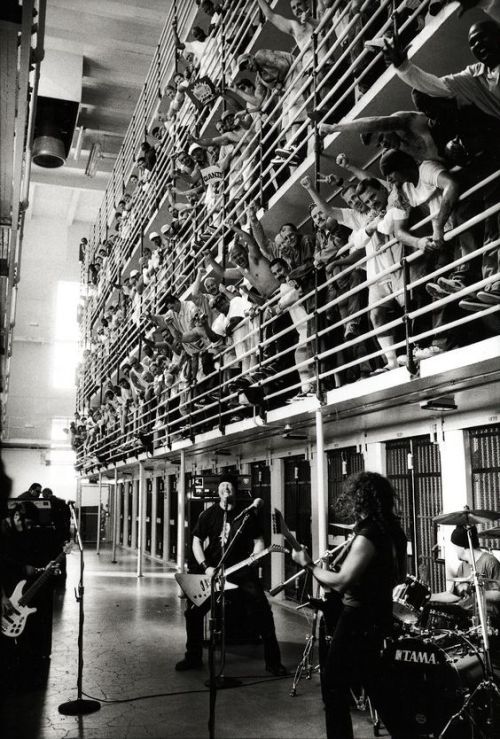

Photo

In 2003, Metallica played a ten-song set in San Quentin Prison, California. The band recorded the music video for St. Anger in the prison and in return for using the prison in their video, played for the inmates and also made a $10,000 donation towards the San Quentin Giants baseball field.

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis being recognised for supporting young and smaller artists x x x

#❤️#Louis supporting other artists#Louis Tomlinson#about Louis#San Quentin#the great Leslie band#mine

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

The California governor, Gavin Newsom, has announced a plan to transform the state’s oldest prison into a center for rehabilitation, education and training, modeled after Norwegian incarceration systems, which are much less restrictive than US facilities.

Newsom told the Los Angeles Times on Thursday that his goal was “ending San Quentin [prison] as we know it” and working to “completely reimagine what prison means”. San Quentin, located on a peninsula in the San Francisco Bay Area and established in 1852, houses nearly 4,000 people, including hundreds on its infamous death row, the largest in the US, which is on track to be dismantled.

The Democratic governor said that by 2025, he plans to transition the massive penitentiary into a final stop of incarceration before individuals are released, with a focus on job training for trades, including plumbers, electricians or truck drivers, the LA Times reported. His recently released budget proposal includes $20m to start the effort.

“The ‘California Model’ the governor is implementing at San Quentin will incorporate programs and best practices from countries like Norway, which has one of the lowest recidivism rates in the world – where approximately three in four formerly incarcerated people don’t return to a life of crime,” the governor’s office said in a statement on Thursday. The prison will be renamed the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center.

Pictured: Instructor Douglas Arnwine hands back papers with comments to his students at San Quentin state prison in April 2022.

The transformation Newsom has described would, at least for San Quentin, mark a fundamental shift from the extremely punitive American system. The US has the highest reported incarceration rate in the world...

Although California is considered a leader in criminal justice reform, the state’s prison system continues to be overcrowded, with thousands of elderly people languishing behind bars and Black residents disproportionately imprisoned for decades due to harsh sentencing laws adopted in the 1990s.

Scandinavian models of incarceration that have garnered increasing attention from some US lawmakers are less focused on punishment and are meant to give imprisoned people support and a sense of normal life behind bars so that they are prepared to reintegrate into society. That can mean access to personal computers, televisions and showers, consistent classes and programming, fresh food, more freedom of movement and stronger connections with the outside world.

“Do you want them coming back with humanity and some normalcy, or do you want them coming back more bitter and more beaten down?” Newsom told the LA Times.

An overhaul of San Quentin would be a huge undertaking, and there are significant unanswered questions about what the transition would mean for its current residents as well as the tens of thousands of others located across the California department of corrections and rehabilitation (CDCR). San Quentin has a long and recent history of scandals involving abuse, overcrowding, guard misconduct and medical neglect. It is also a prison that has significantly more programming than some of the remote and rural CDCR prisons, with a renowned podcast produced by incarcerated San Quentin journalists.

The governor’s office noted research showing that every $1 spent on rehabilitation saves more than $4 on costs of re-incarceration; that people who enroll in education programs behind bars are 43% less likely to return to prison; and that crime survivor groups say victims prefer sentences that include programming designed to prevent recidivism...

Assemblymember Mia Bonta noted that California spends $14.5bn on prisons each year – $106,000 a person – but traditionally puts only about 3.4% toward rehabilitation: “It’s time for a significant paradigm shift.”

One of the reporters in attendance was Steve Brooks, an incarcerated journalist and editor of the San Quentin News paper, who asked the governor how the Scandinavian model would be adopted in a prison where residents remain concerned about overcrowding and the living conditions. Brooks also said people were concerned that those convicted of violent offenses would be excluded from programs under a new system. Newsom responded, “I’m not looking to cherry pick certain offenses. I’m for people who are committed, not passively interested, in changing themselves.”

-via The Guardian, 3/17/23

#california#united states#us politics#prison#prison industrial complex#prison reform#incarceration#san quentin#scandinavian#gavin newsom#good news#hope

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bobby Beausoleil photographed by Peter Beard for Interview Magazine, ca. 1971-72.

"All of my tattoos were done while I’ve been in prison, all designed by me, many tattooed by me. Other jailhouse tattoo artists did the work in the places where I couldn’t reach with my right hand or see with a mirror."

#mygirlhatesmyheroin#bobby beausoleil#peter beard#interview magazine#tattoos#san quentin summer#1971#1972#1970s#70s#black and white photography#manson family#charles manson#true crime#gary hinman

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

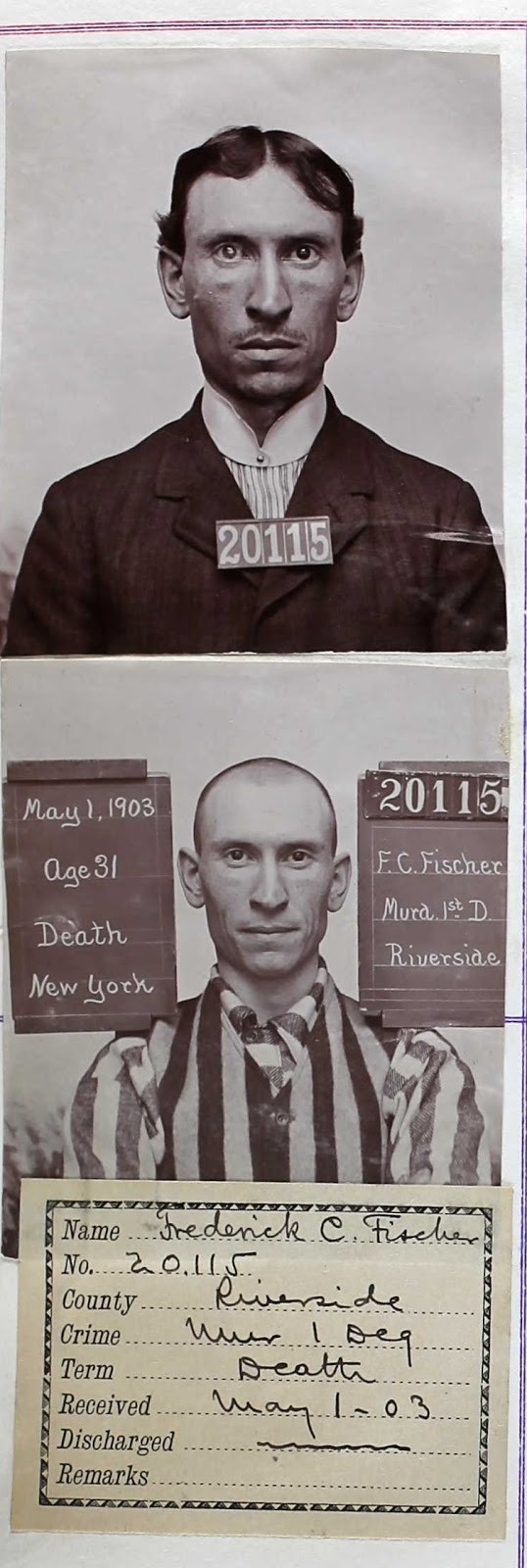

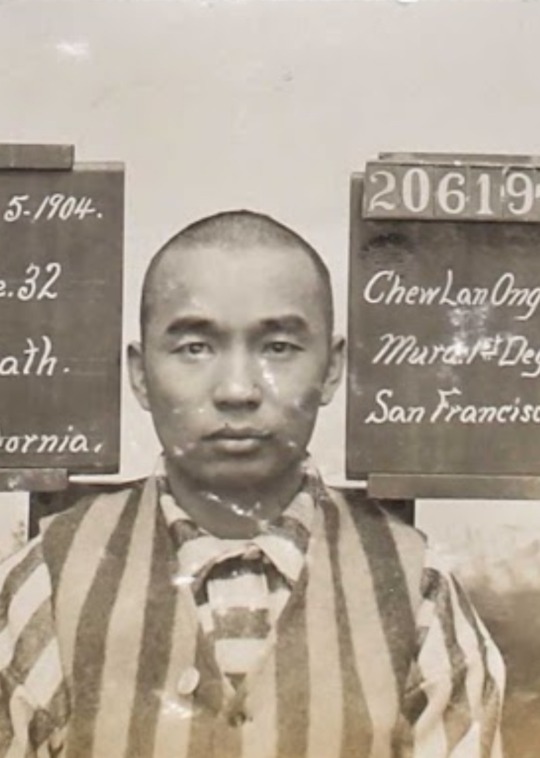

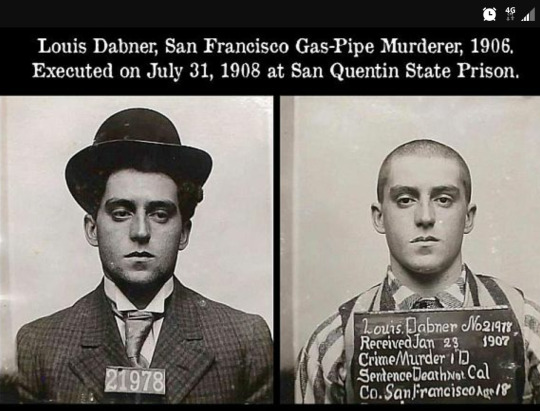

San Quentin California Death Row Convicts on Intake Day

Each of these convicts were ultimately hanged at San Quentin for murder.

The civilian clothes and haircuts followed by prison stripes buttoned at the neck, shaved heads, and prison ID cards listing their crimes are standard.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

San Quentin, I hate every inch of you

You've cut me and you've scarred me through and through

And I'll walk out a wiser, weaker man

Mr. Congressman, you can't understand

San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I'll be different when you're through?

You bend my heart and mind, and you warp my soul

Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold

✯ San Quentin, Johnny Cash

0 notes

Photo

Ann Sheridan in SAN QUENTIN (1937) dir. Lloyd Bacon

438 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metallica at San Quentin Prison, 2003. Photo by Danny Clinch.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fourth Sunday of Advent: The Prayer I Heard on Death Row

"Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word." (Luke 1:38)

In 2019, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a moratorium on the death penalty. He then ordered the transfer of death row inmates at San Quentin State Prison to other maximum-security prisons in California. These changes elicited concern from San Quentin inmates themselves, as well as the chaplains who care for their spiritual welfare. It is a little-known fact that San Quentin is one of the few prisons in the state to have a dedicated Catholic chapel.

Compelled by pastoral concern, the California Catholic Conference arranged for four bishops of California, including myself, to speak and minister to the inmates earlier this year in March. The prison’s Catholic chaplain, Father Manny Chavira, and warden graciously arranged what can only be described as a graced encounter with those truly on the fringe of society and the Church. In about five hours, my fellow bishops and I developed a good sense of the culture, issues, fears, and freedoms behind the walls of this infamous prison.

As we walked down the narrow hallway, we could hear the men yelling to each other from their private cells, which do not allow for visual contact. This was part of the cold, harsh reality of prison life and the culture of San Quentin. The clanking of steel rang shrill as the guards opened and closed gates. This permeating sound through the chilly air of the old cinder block building still rings in my consciousness.

It is not a place easily forgotten. Yet even in these disparate settings, grace still finds a way, and miracles happen.

I was deeply moved to listen to one inmate, who I’ll call Carlos, recount his faith conversion. He shared that he first prayed — and used this term loosely — to Our Lady of Guadalupe, not knowing exactly who she was or what to say. Never having tried such a thing before, Carlos related the words of his first ‘prayer’ to Mary, and truthfully, I was brought to tears by the sheer humanity and humility of his address to Our Lady: “I am not sure exactly who you are, but I know you are sacred from how people treat you. If you could, would you please help me because I am feeling really lost.”

After this, he felt that he heard a voice reply, “You are my son. I love you.”

This humble interaction is not so dissimilar to the story of Mary we hear in the Gospel reading for the Fourth Sunday of Advent. The angel Gabriel appears to a young Mary, who is frightened and confused by the message sent to her that she would “conceive in [her] womb and bear a son,” the Messiah. She is just a young girl at the time, and the future that is laid out for her seems bewildering and uncertain.

But even in her mystification, Mary humbly responds: "Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word."

Mary relies on faith even when the way forward isn’t clear. Because of her faith, God becomes incarnate. (In a few days, we will all join in celebration of that miracle born in humility.)

Like Mary, Carlos relied on faith, and his humility made way for God to enter his heart. His prayer experience inspired him to learn about and eventually become a fully initiated Catholic. He found himself reading the Bible, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, and about the lives of the saints. He now ministers to his fellow inmates.

Mary and Carlos’ stories remind us that God is actively seeking us, even in the moments we are most lost and uncertain. This Advent I pray our faith can look a little more like theirs: honest, humble, and open to the future God holds for us.

- Bishop Oscar Cantú on Catholic Mobilizing Network

#catholic#catholicism#advent#bishop oscar cantu#catholic mobilizing network#cmn#death row#prayer#san quentin#prison#our lady of guadalupe

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the 43 years that I’ve spent in a small cell at San Quentin, I’ve felt grass under my feet only five times.

The first time was after I had spent seven years in the isolation unit because I refused to cut my hair. I’m Monache and Cherokee. They punished me despite the fact that it’s my tradition and spiritual belief as a Native American to grow my hair long.

But outside the isolation unit there was a row of grass that they really took care of. As the guards led me out of that building, I stepped off the concrete path so I could feel the grass and dirt under my feet. The smell and feel of grass is still part of me.

I'm sure most free people don’t even realize that they take something like that for granted, but it’s the little things that I cherish the most. I often think back to growing up at Big Sandy — the coyotes and foxes, the geese and deer and wild turkeys. There were 17 of us living together in three cabins, and it only cost about $80 a month to feed us. We ate venison, rabbit and turkey, and we had a garden. We always had homemade biscuits, tortillas, frybread and cornbread, and there were always beans cooking on the back of the potbellied stove. Those thoughts, along with the self-discipline I’ve developed in here, have helped sustain me.

I can say that conditions in the isolation unit have changed since 1980, when I was there for the first time. Back then, there was a hole in the floor for a toilet. The toilets were supposed to be flushed once every 24 hours, but they rarely were.

We were supposed to get 1,500 calories a day. But we got one meatball in the morning and one at night with half a slice of bread. Anytime people acted up, the guards would pepper spray them. Sometimes, guards would spray people just to see how they’d react.

Guards would also take our mattresses in the morning and give them back at night — presumably because they didn’t want inmates destroying them. But nine times out of 10 you wouldn’t get your mattress back. It would be someone else’s, and there might be feces on it or urine on it. After five times, I told them, “No, I don’t want a mattress anymore.” I haven’t had one since then. I just fold a blanket in half and sleep on it. I also haven’t had a pillow — I use a roll of toilet paper, and I’m comfortable with that.

In the death-row cells where I’ve spent most of my time, I’m still in isolation — it’s just not as bad. My current cell is roughly 4 1/2 feet by 10 feet. Along with my toilet, bed and sink, I’ve got a shelf, two lights and a typewriter. I have some CDs and a CD player with a radio. I also have some photos and eight posters of Harley Davidsons. My dad was a biker.

But I’m still locked up all the time, and I don’t come out unless I’m handcuffed. I go to the shower, I’m handcuffed. I go to medical or the yard, I’m handcuffed. A guard is always watching. It’s like I’m in a zoo.

We do have Native worship services at San Quentin, but our religious adviser doesn’t do it right. He has a sacred pipe that he allows everybody to touch, and that’s bad medicine. You’re not supposed to touch the pipe or anything sacred like that if you have blood on your hands. If you’ve killed someone in self-defense or to protect your family or your property, that’s one thing. But if you kill somebody just to kill, it’s called having blood on your hands. That’s why I go to other worship services, so I can absorb other teachings and learn about different religions.

We used to have four powwows a year. Tribes from the Bay Area and all the way up north would offer buffalo, elk, venison and fish. Now we’re lucky if we have one powwow per year. The reason is that the religious adviser would tell the tribes we were going to have a powwow on a certain date and after the tribes caught fish and deer for it, he’d say, “Well, now we’re going to have it next month.” You can’t do that.

When we did have a powwow, we’d get a two-ounce serving of salmon and everything else would be prison food. The prison wouldn’t allow people to bring in buffalo meat because they said bones were a security risk. They could just take the meat off the bone and then bring it in, but they won’t do that. You’ve got these brothers and sisters in the free world going out and getting it for us, and we can’t have it.

Meanwhile, my daily routine is the same as it has been for decades. I wash up, make sure my cell is clean, then I say my prayers and I meditate for 20 minutes to an hour. After that, I turn on the radio, exercise, maybe type a letter and get my breakfast. I work on my case for about three hours a day. We have a law library, but you have to get on a list, so you might go once a month. Every week, we can put in requests for a law book we need. You may be placed on a waiting list for the book, but it's better than nothing.

I go to the yard with other people twice a week for a total of six hours — unless it’s foggy or there’s been an incident and we’re in lockdown. I get to shower for 15 minutes every other day with a guard standing by. Otherwise, I’m in my cell.

Since my sentence was reduced to life without possibility of parole in 2019, I have the option of transferring to a cell in the general population. But I’d have to go to a Level 4 maximum security unit where there’s a lot of violence. Other inmates would want to test me because I’ve been on death row.

I also have the option of moving to a different prison, but my legal team is in this area. I might end up 500 miles away; that would make it harder for them to come and see me when they have to.

And so, I await a court date. It could be in a month, it could be in six months. We don’t know. Meanwhile, I just try to be the best person I can be so that I’m content with myself and can go to sleep at night and say, “Well, I did a good day. I didn’t do anybody wrong, I didn’t lie to anybody.”

People have asked me, “How did you make it through 43 years in prison?” And I say, “By being Native.” Being Native gives me the strength to overcome all of this — not just for me, but for all our brothers and sisters. Society cannot break our spirit.”

- DOUGLAS RAY STANKEWITZ as told to RICHARD ARLIN WALKER, “California’s Longest Serving Death-Row Prisoner On Pain, Survival and Native Identity.” The Marshall Project. March 18, 2022.

#san quentin#san quentin prison#life inside#words from the inside#life prisoner#life sentence#solitary confinement#monache#cherokee#indigenous people#life in prison#california prisons#american prison system#crime and punishment#death row#american indians

130 notes

·

View notes