#arthur lett-haines

Text

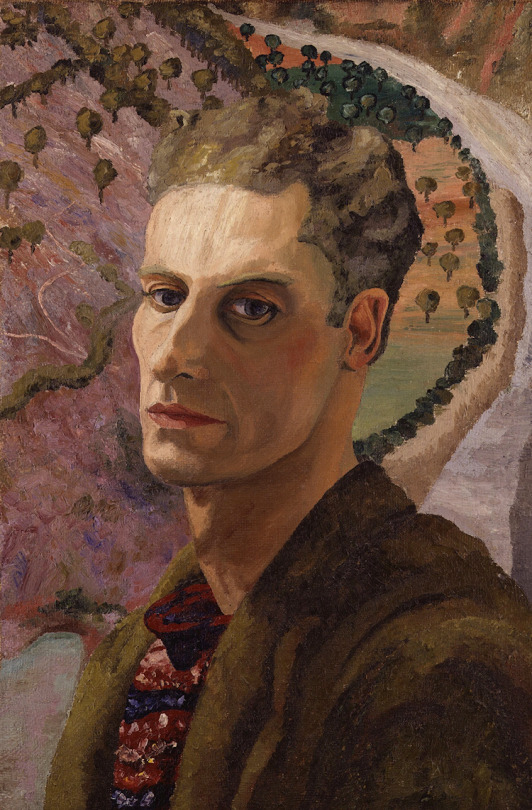

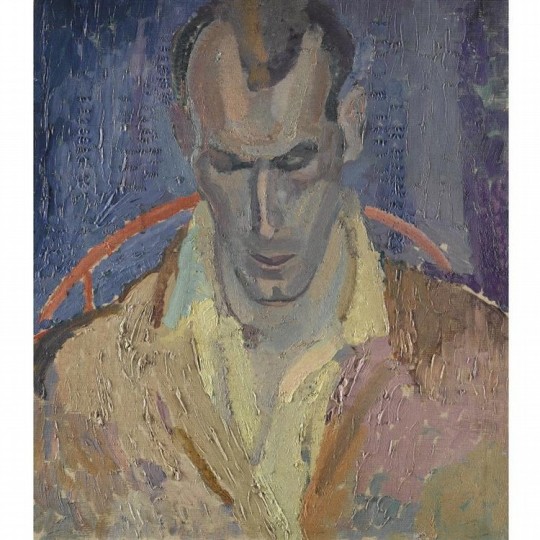

Cedric Morris - Self-Portrait, c. 1930

Cedric Morris and his partner Arthur Lett-Haines with the macaw Rubio, c. 1930

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Lett-Haines

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

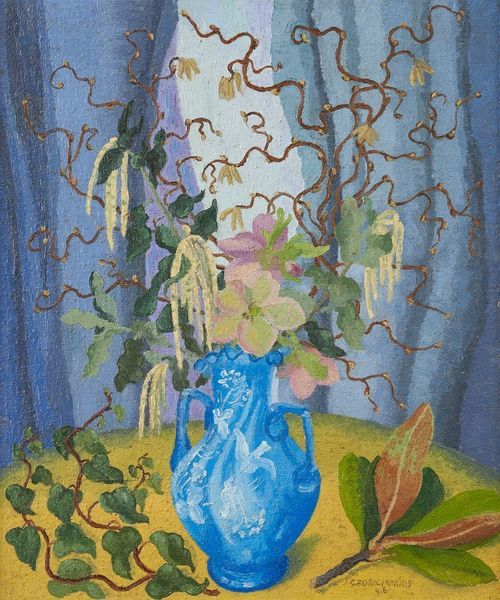

Cedric Morris

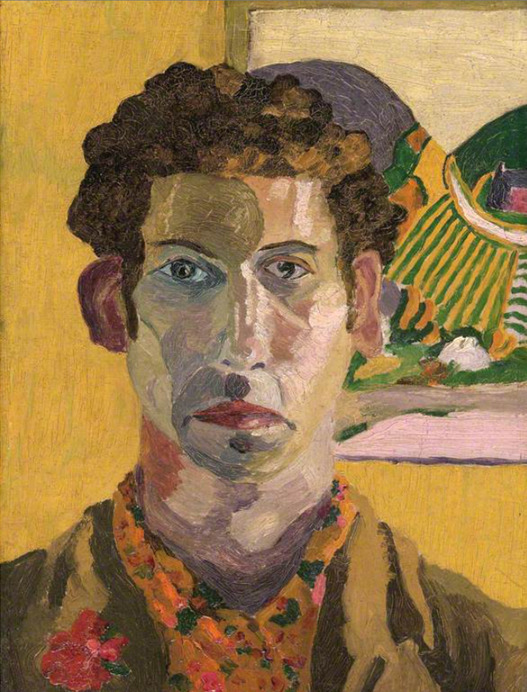

Self portrait by Cedric Morris (1919)

Cedric Lockwood Morris was born on December 11th 1889 at Matcham Lodge, Sketty, Swansea. He was the first-born child of George Lockwood Morris, an industrialist, iron founder and prominent rugby player who had played for Wales and his wife Wilhelmina (née Cory). Both of Cedric’s mother and father hailed from well-to-do families who owned industrial…

View On WordPress

#Art#Art Blog#Art History#Arthur Lett Haines#Benton End#Cedric Morris#East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing#Floral painter#Frances Hodgkins#Welsh artists

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Denis Wirth-Miller (1915-2010), born Wurtmüller in Folkestone to a Bavarian father and English mother.

Denis Wirth-Miller: Bohemian artist who enjoyed a close association with Francis Bacon.Denis Wirth-Miller was one of a group of artists who for many years injected the spirit of bohemia into the life of Wivenhoe, a small shipbuilding and repairing town on the Essex coast. The jollifications of Wirth-Miller, his partner, the James Bond illustrator Richard "Dickie" Chopping, and the painter Francis Bacon remain the stuff of local legend.

Such stories, true or untrue – among the latter is one that after Bacon's death his former Wivenhoe house was kept as a shrine by Denis and Dickie – have tended to overshadow Wirth-Miller's achievements as a painter. One recognition of this will be a forthcoming small retrospective at the Minories Art Gallery, Colchester.

Also undermining Wirth-Miller's reputation was the fact that from the early 1970s sight problems hindered him and that latterly he suffered from dementia. All this must have been hard for a man who had shown in London's leading galleries and had work in the collections of the Queen, the Arts Council and Contemporary Art Society.

Wirth-Miller was born in Folkestone, Kent, in 1915, where his Bavarian father Johann Wirthmiller (Denis later Anglicised his name) ran a busy hotel. Wirth-Miller's mother moved him to Bamburgh in her home county of Northumberland, where he was raised by his grandmother.After school, he joined Tootal Broadhurst Lee, the textile manufacturers in Manchester, where innate talent prompted his appointment as a designer. After arriving in London early in 1937 he met Dickie Chopping, who moved into one of the painter Walter Sickert's former studios in north London, where Denis was living. Thus began a lifelong relationship; in December 2005 they became the first in Colchester to make a civil partnership.

It was not without disagreements, even how about they first met – according to Chopping at a Regent's Park charity garden party, according to Wirth-Miller at the Café Royal, a celebrated meeting point for gay men. A friend was concerned about the vulnerability of the Sickert flat to bomb damage and advised them to leave London, lending them the dilapidated Felix Hall in Kelvedon, Essex. There, they scraped a living gardening and other jobs.Then, importantly, they met the painters Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines, who had established the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, first at Dedham and, when that was destroyed by fire, at Benton End. The artist Mollie Russell-Smith recalled how, as a student lacking an easel, with trepidation she knocked on the door at Benton End and it was "flung open by three young men" – Chopping, Wirth-Miller and Lucian Freud.

"They bundled me in, assuming that I had come to be a student, and Dickie showed me all over the house with great enthusiasm and charm. I was enchanted."

https://www.independent.co.uk/.../denis-wirthmiller...

https://www.apollo-magazine.com/denis-wirth-miller-bacon.../

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

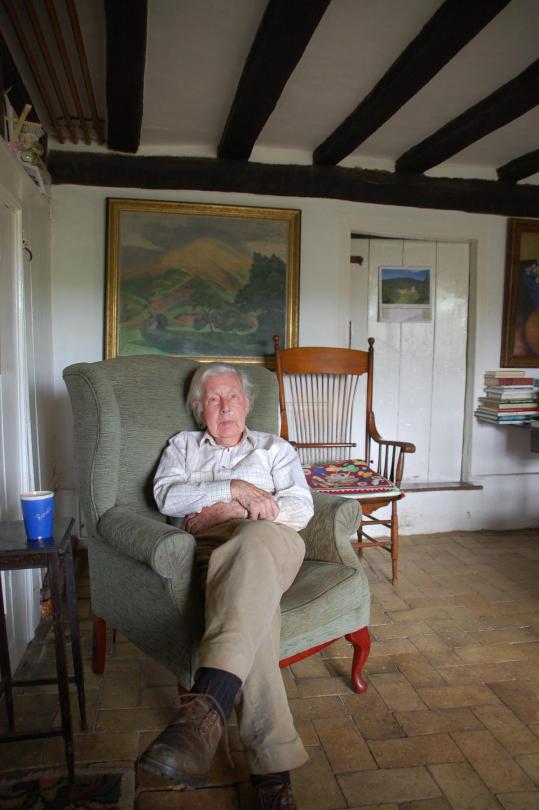

In the summer of 1967, Ronald Blythe cycled from his home in the Suffolk hamlet of Debach to the neighbouring village of Charsfield. There he listened to the voices of blacksmiths, gravediggers, nurses, horsemen and pig farmers. He gave them names from gravestones and placed them in a fictional village. Akenfield, a portrait of a rural life rapidly disappearing from view, was immediately acclaimed as a classic when it was published in 1969.

Never out of print and read and studied around the world, Akenfield made Blythe famous and perhaps overshadowed the many other fruits of his long years of writing – short stories, poems, histories, novels and, in later life, luminous essays and a superb weekly diary that the Church Times published for 25 years until 2017. Blythe, who has died aged 100, is regarded by his peers and many readers as the finest contemporary writer on the English countryside.

The eldest of six children, Blythe was born in Acton, near Lavenham, into a family of farm labourers rooted in rural Suffolk. His surname comes from the Blyth, a small Suffolk river, but his mother and her family were Londoners. His mother, Matilda (nee Elkins), a nurse, passed to him her love of books. Although Blythe left school at 14, by then he had already established a voracious reading habit – “never indoors, where one might be given something to do,” he remembered – which became his education.

His father, Albert, had served in the Suffolk Regiment and fought at Gallipoli and Blythe was conscripted during the second world war. Early on in his training, his superiors decided he was unfit for service – friends said he was incapable of hurting a fly – and he returned to East Anglia to work, quietly, as a reference librarian in Colchester library.

He befriended local writers including the poet James Turner, who helped his passage into a bohemian, creative Suffolk circle that included Sir Cedric Morris, who taught Lucian Freud and Maggi Hambling and lived nearby with his partner, Arthur Lett-Haines. Blythe “longed to be a writer”, he said, and he listened and learned – inspired by the example of poet friends including Turner (the unnamed poet in Akenfield) and WR Rodgers of how to live with very little money. “It was a kind of apprenticeship,” he once recalled.

Most importantly, in 1951 he met the artist Christine Kühlenthal, wife of the painter John Nash. Kühlenthal encouraged his writing and championed him: Blythe edited Aldeburgh festival programmes for Benjamin Britten and even ran errands for EM Forster, who took a shine to the shy young man. Blythe helped Forster compile an index for Forster’s 1956 biography of his great-aunt, Marianne Thornton.

Blythe’s first, Forster-inspired novel, A Treasonable Growth, was published in 1960. He followed it in 1963 with The Age of Illusion, a social history of life in England between the wars. He earned money from journalism, being a publishers’ “reader” and editing a series of classics – including one of his heroes, the essayist William Hazlitt – for the Penguin English Library.

After a stint living in Aldeburgh, recalled in an elegiac and characteristically discreet memoir, The Time by the Sea (2013), he moved to a cottage in Debach. In the mid-1960s, he was befriended by the American novelist Patricia Highsmith. “I admired her enormously. She was a very strange, mysterious woman. She was lesbian but at the same time she found men’s bodies beautiful,” he remembered. One evening, after a Paris literary do, they slept together; he told a friend they were both curious “to see how the other half did it”.

Blythe said the idea for Akenfield (he took the name from the old English “acen” for acorn) arrived as he tramped the Suffolk fields pondering the anonymity of most farm labourers’ lives. His friend Richard Mabey remembers it being commissioned by Viking as the lead title for a short-lived series on village life around the world.

Over 1967 and 1968, he listened to the citizens of Charsfield, recreating authentic country voices while somehow adding a poetry of his own. The result was a portrait of the “glory and bitterness” of the countryside: the penury and yet deep pride of the old, near-feudal farming life, and its obliteration in the 60s by a second agricultural revolution alongside the arrival of the car and television.

The village voices were never sentimental about country life, and nor was Blythe: as well as stories of how to make corn dollies, there were quiet revelations of incest, and the district nurse recounted the old days when old people were stuffed into cupboards. Old labourers remembered the “meanness” of farmers who had treated their workers like machines because the big rural families delivered a seemingly endless supply of farm-fodder.

Ecstatic reviews of this “exceptional” and “delectable” book in Britain spread to North America, where Time praised it, John Updike loved it and Paul Newman wanted to film it. But some oral historians were suspicious that Blythe had not recorded his conversations.

Blythe turned down a film offer from the BBC but eventually accepted a pitch from the theatre director Peter Hall, a fellow Suffolk man. Blythe wrote a new synopsis inspired by the unfilmable book, and Hall asked ordinary rural people to improvise scenes with no script. Blythe oversaw every day of filming and played an apt cameo as a vicar. Nearly 15 million people watched Akenfield when it was broadcast on London Weekend Television in early 1975.

Blythe’s next book, The View in Winter (1979), was a prescient examination of old age in a society that did not value it, at a time when more people than ever reached it. The “disaster” suffered by the old, he wrote, is “nobody sees them any more as they see themselves”. Blythe regarded it as his best book. While he was writing it, Kühlenthal died, and Blythe moved into the Nashes’ old farm, Bottengoms, to look after the elderly Nash. When Nash died a year later, he left the house to Blythe. There Blythe lived for the rest of his life, writing beautifully about his home in At the Yeoman’s House (2011).

In later years, Blythe drew praise for his short stories and essays, including a series of meditations on the 19th-century rural poet John Clare. Many writers who were later grouped together as “nature writers” became his friends, including Mabey, Robert Macfarlane and Roger Deakin.

Blythe never married, never lived with anyone, and kept his personal life veiled. Interviewed by the Observer in November 1969, he was judged “intensely private”. He disclosed nothing in his published writing about his love affairs with men, or indeed his one-night stand with Highsmith.

He was almost as reticent about his faith, but his writing was deeply suffused in his Christian beliefs and his knowledge of the scriptures. He was a lay reader – deputising for vicars across several parishes – and became a lay canon of St Edmundsbury Cathedral, but turned down the chance to become a priest.

Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury and an admirer of Blythe’s writing, believed Blythe used the Christian year of festivals as “a steady backdrop” for his writing and thinking, which was liberated by his faith. The writer Ian Collins, a good friend of Blythe in his later years, felt it was Blythe’s lack of formal education or “training” that liberated his original thinking and elegant prose style.

Blythe was politically radical throughout his life, a Labour voter who joined peace vigils outside St-Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Friends were surprised when he accepted a CBE in 2017, around the time he was gently “retired” from public speaking and writing as his short-term memory faded. When he reached 100, he was still well enough to sign 1,500 copies of a new compilation of his best Church Times columns.

The old people who thrived in The View in Winter were those, Blythe concluded, who were able to preserve their “spiritual vitality, a vividness, an imaginative sort of energy”. This credo served him well as he grew older, although he was mistaken in another respect. The old, he wrote, are “cared for, surrounded with kindliness, and people are often interested in what they say; but they are not truly loved and they know it”.

Blythe was much loved in later life. A roster of devoted friends he called his “dear ones” visited him daily, supplied him with hot meals and ensured he could live out his years at Bottengoms.

🔔 Ronald George Blythe, writer, born 6 November 1922; died 14 January 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

À l'été 1967, Ronald Blythe a pédalé de sa maison dans le hameau Suffolk de Debach au village voisin de Charlsfield. Là, il a écouté les voix des forgerons, des fossoyeurs, des infirmières, des cavaliers et des éleveurs de porcs. Il leur a donné des noms sur des pierres tombales et les a placés dans un village fictif. Akenfield, portrait d'une vie rurale en voie de disparition rapide, a été immédiatement acclamé comme un classique lors de sa publication en 1969.Jamais épuisé et lu et étudié dans le monde entier, Akenfield a rendu Blythe célèbre et a peut-être éclipsé les nombreux autres fruits de ses longues années d'écriture - nouvelles, poèmes, histoires, romans et, plus tard dans la vie, des essais lumineux et un superbe hebdomadaire. journal que le Church Times a publié pendant 25 ans jusqu'en 2017. Blythe, décédé à l'âge de 100 ans, est considéré par ses pairs et de nombreux lecteurs comme le meilleur écrivain contemporain de la campagne anglaise.Aînée de six enfants, Blythe est née à Acton, près de Lavenham, dans une famille d'ouvriers agricoles enracinée dans le Suffolk rural. Son nom de famille vient de la Blyth, une petite rivière du Suffolk, mais sa mère et sa famille étaient londoniennes. Sa mère, Matilda (née Elkins), infirmière, lui a transmis son amour des livres. Bien que Blythe ait quitté l'école à 14 ans, il avait déjà établi une habitude de lecture vorace - "jamais à l'intérieur, où l'on pourrait avoir quelque chose à faire", se souvient-il - qui est devenue son éducation.Son père, Albert, avait servi dans le Suffolk Regiment et combattu à Gallipoli et Blythe fut enrôlé pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. Au début de sa formation, ses supérieurs ont décidé qu'il était inapte au service - des amis disaient qu'il était incapable de blesser une mouche - et il est retourné à East Anglia pour travailler, tranquillement, comme bibliothécaire de référence à la bibliothèque de Colchester.Il s'est lié d'amitié avec des écrivains locaux, dont le poète James Turner, qui a contribué à son passage dans un cercle bohème et créatif du Suffolk qui comprenait Sir Cedric Morris, qui a enseigné à Lucian Freud et Maggi Hambling et a vécu à proximité avec son partenaire, Arthur Lett-Haines. Blythe "aspirait à être écrivain", a-t-il dit, et il a écouté et appris - inspiré par l'exemple d'amis poètes, dont Turner (le poète anonyme d'Akenfield) et WR Rodgers, sur la façon de vivre avec très peu d'argent. "C'était une sorte d'apprentissage", se souvient-il un jour.Surtout, en 1951, il rencontre l'artiste Christine Kühlenthal, épouse du peintre John Nash. Kühlenthal a encouragé son écriture et l'a défendu : Blythe a édité les programmes du festival d'Aldeburgh pour Benjamin Britten et a même fait des courses pour EM Forster, qui a fait briller le jeune homme timide. Blythe a aidé Forster à compiler un index pour la biographie de Forster de 1956 sur sa grand-tante, Marianne Thornton.Le premier roman de Blythe, inspiré de Forster, A Treasonable Growth, a été publié en 1960. Il l'a suivi en 1963 avec The Age of Illusion, une histoire sociale de la vie en Angleterre entre les deux guerres. Il gagnait de l'argent grâce au journalisme, étant « lecteur » d'éditeurs et éditant une série de classiques – dont l'un de ses héros, l'essayiste William Hazlitt – pour la Penguin English Library.Ronald Blythe chez lui dans le Suffolk en 2010. Photographie: Eamonn McCabe / The GuardianAprès un passage à Aldeburgh, rappelé dans un mémoire élégiaque et typiquement discret, The Time by the Sea (2013), il s'installe dans un cottage à Debach. Au milieu des années 1960, il se lie d'amitié avec la romancière américaine Patricia Highsmith. "Je l'admirais énormément. C'était une femme très étrange et mystérieuse. Elle était lesbienne mais en même temps elle trouvait les corps des hommes beaux », se souvient-il. Un soir, après une soirée littéraire parisienne, ils couchèrent ensemble ; il a dit à un ami qu'ils étaient tous les deux curieux "de voir comment l'autre moitié l'a fait".

Blythe a déclaré que l'idée d'Akenfield (il a pris le nom du vieil anglais "acen" pour gland) est arrivée alors qu'il parcourait les champs du Suffolk en pensant à l'anonymat de la vie de la plupart des ouvriers agricoles. Son ami Richard Mabey se souvient qu'il a été commandé par Viking comme titre principal d'une série éphémère sur la vie des villages à travers le monde.Au cours de 1967 et 1968, il a écouté les citoyens de Charsfield, recréant des voix country authentiques tout en y ajoutant sa propre poésie. Il en résulte un portrait de la « gloire et de l'amertume » de la campagne : la misère et pourtant la fierté profonde de l'ancienne vie paysanne quasi féodale, et son effacement dans les années 1960 par une seconde révolution agricole parallèlement à l'arrivée de la voiture et de la voiture. télévision.Les voix du village n'ont jamais été sentimentales à propos de la vie à la campagne, et Blythe non plus : en plus des histoires sur la fabrication de chariots de maïs, il y a eu des révélations discrètes d'inceste, et l'infirmière du district a raconté l'ancien temps où les personnes âgées étaient entassées dans des placards. Les vieux ouvriers se souvenaient de la « méchanceté » des agriculteurs qui avaient traité leurs ouvriers comme des machines parce que les grandes familles rurales livraient une quantité apparemment inépuisable de fourrage agricole.Akenfield de Ronald Blythe a été publié en 1969Les critiques enthousiastes de ce livre « exceptionnel » et « délicieux » en Grande-Bretagne se sont répandues en Amérique du Nord, où Time l'a loué, John Updike l'a adoré et Paul Newman a voulu le filmer. Mais certains historiens oraux se méfiaient du fait que Blythe n'avait pas enregistré ses conversations.Blythe a refusé une offre de film de la BBC mais a finalement accepté un pitch du directeur de théâtre Peter Hall, un autre homme du Suffolk. Blythe a écrit un nouveau synopsis inspiré du livre infilmable, et Hall a demandé aux ruraux ordinaires d'improviser des scènes sans scénario. Blythe a supervisé chaque jour le tournage et a joué un camée approprié en tant que vicaire. Près de 15 millions de personnes ont regardé Akenfield lors de sa diffusion sur London Weekend Television au début de 1975.Le prochain livre de Blythe, The View in Winter (1979), était un examen prémonitoire de la vieillesse dans une société qui ne la valorisait pas, à une époque où plus de gens que jamais l'atteignaient. Le "désastre" subi par les anciens, écrit-il, c'est que "personne ne les voit plus comme ils se voient eux-mêmes". Blythe le considérait comme son meilleur livre. Pendant qu'il l'écrivait, Kühlenthal mourut et Blythe emménagea dans l'ancienne ferme des Nash, Bottengoms, pour s'occuper du vieux Nash. Lorsque Nash mourut un an plus tard, il laissa la maison à Blythe. Là, Blythe a vécu pour le reste de sa vie, écrivant magnifiquement sur sa maison dans At the Yeoman's House (2011).Plus tard, Blythe a attiré des éloges pour ses nouvelles et ses essais, y compris une série de méditations sur le poète rural du XIXe siècle John Clare. De nombreux écrivains regroupés plus tard sous le nom d'« écrivains de la nature » devinrent ses amis, dont Mabey, Robert Macfarlane et Roger Deakin.Blythe ne s'est jamais marié, n'a jamais vécu avec personne et a gardé sa vie personnelle voilée. Interrogé par The Observer en novembre 1969, il est jugé « intensément privé ». Il n'a rien révélé dans ses écrits publiés sur ses amours avec les hommes, ni même sur son aventure d'un soir avec Highsmith.Une image tirée du film de Peter Hall sur Akenfield. Blythe a supervisé chaque jour de tournage et a joué un camée en tant que vicaire. Photographie: BFIIl était presque aussi réticent à propos de sa foi, mais son écriture était profondément imprégnée de ses croyances chrétiennes et de sa connaissance des Écritures. Il était un lecteur laïc - remplaçant les vicaires dans plusieurs paroisses - et est devenu chanoine laïc de la cathédrale St Edmundsbury, mais a refusé la possibilité de devenir prêtre.

Rowan Williams, l'ancien archevêque de Cantorbéry et admirateur de l'écriture de Blythe, pensait que Blythe utilisait l'année chrétienne des festivals comme «une toile de fond stable» pour son écriture et sa pensée, libérées par sa foi. L'écrivain Ian Collins, un bon ami de Blythe dans ses dernières années, a estimé que c'était le manque d'éducation formelle ou de «formation» de Blythe qui avait libéré sa pensée originale et son style de prose élégant.Blythe a été politiquement radical tout au long de sa vie, un électeur travailliste qui a rejoint les vigiles pour la paix à l'extérieur de St-Martin-in-the-Fields à Londres. Des amis ont été surpris lorsqu'il a accepté un CBE en 2017, à peu près au moment où il a été doucement «retraité» de la parole et de l'écriture en public alors que sa mémoire à court terme s'estompait. Lorsqu'il a atteint 100 ans, il était encore assez bien pour signer 1 500 exemplaires d'une nouvelle compilation de ses meilleures chroniques du Church Times.Les personnes âgées qui ont prospéré dans The View in Winter étaient celles, a conclu Blythe, qui ont pu préserver leur « vitalité spirituelle, une vivacité, une sorte d'énergie imaginative ». Ce credo lui a bien servi en vieillissant, bien qu'il se soit trompé sur un autre point. Les anciens, écrit-il, sont « soignés, entourés de bienveillance, et les gens s'intéressent souvent à ce qu'ils disent ; mais ils ne sont pas vraiment aimés et ils le savent ».Blythe était très aimé plus tard dans la vie. Une liste d'amis dévoués qu'il appelait ses « êtres chers » lui rendait visite quotidiennement, lui fournissait des repas chauds et s'assurait qu'il puisse vivre ses années à Bottengoms. Ronald George Blythe, écrivain, né le 6 novembre 1922 ; décédé le 14 janvier 2023

0 notes

Photo

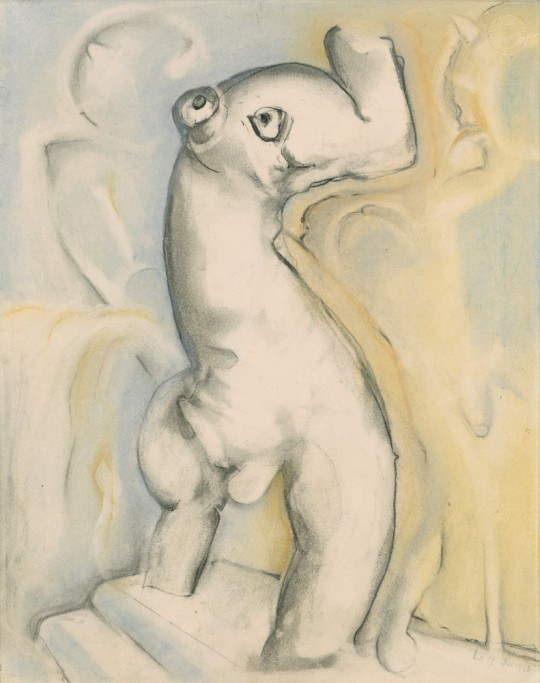

Arthur Lett-Haines (British,1894 – 1978)

Powers in Atrophe ,1922

Ink, watercolour and chalk on paper

437 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cedric Morris was born in Sketty, Swansea on the 11th of December, 1889, to a Welsh industrialist father, George Lockwood Morris, and Wilhelmina Cory. After spending some of his youth working in Ontario and New York, Cedric returned to South Wales and eventually started painting and studied in Montparnasse, Paris, until the First World War.

After he was discharged in 1917, Cedric went to Cornwall and studied plants, where he was friends with painter Frances Hodgkins. At the end of the war, Cedric met Arthur Lett-Haines in London, where they fell in love and became lifelong partners. They planned to move to America together with Arthur’s then wife, Gertrude Aimee Lincoln, who then left for America on her own. They lived together in Newlyn, in Cornwall, in Paris and London, where Cedric continued his painting with success.

In the 1930s, they moved to ‘a pink-coloured house’ in Higham, Suffolk and started the East Anglian School of Painting in 1937. Students of Cedric’s included Vivien Gruble, Lucian Freud, Maggi Hambling and Joan Warburton.

Though Cedric had relationships with John Aldrigde and Paul Odo, and Arthur had his own affairs, they spent their lives together, until Cedric’s death on the 8th of February, 1982. Arthur died in 1984 and they are both buried at Friars Road Cemetery, Hadleigh - Cedric’s gravestone was made in Welsh slate.

Images: Self Portrait by Cedric Morris (c. 1930), via NPG; Cedric Morris by Frances Hodgkins; Self Portrai (1919), at National Museum Wales; Portrait of Arthur Lett-Haines by Cedric Morris (1925).

#cedric morris#art#arthur lett-haines#lgbt history#gay history#queer history#welsh queer history#otd#on this day#m#by m#nmw#npg#interesting similarities to other welsh queer people I've mentioned like nina hamnett#there's of course much more history of cedric and arthur but just a short post

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passage about Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines from my class textbook that I think about a lot

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Lett-Haines

Powers in Atrophe

1922

Tate

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In 1929 Cedric Morris and his partner Arthur Lett-Haines left city life behind them and escaped to the countryside. Surrounded by rolling hills and wild, untamed nature in West Suffolk, Morris's creativity flourished - both on canvas and in his beloved gardens - and in the decade that followed he painted some of his greatest works.

During the wartime years Morris and Lett kept their recently established art school - the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing - open for pupils and transformed areas of their land at Benton End into a well-ordered vegetable garden. During this period of isolation and uncertainty Morris found solace in his art and gardens and some of his most introspective works were painted at this date.

After the war Morris was free to roam the English countryside once again and visited, amongst other places, Wales, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, each of which provided an interesting landscape quite unlike Suffolk which he deftly captured in paint. In 1950, after receiving a new passport, Morris was able to once again travel abroad and over the decades that followed his time was increasingly divided between painting, gardening, teaching and travelling.

https://philipmould.com/.../17-the-call-to-the-country.../

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

📷 Photo above: Benton End, the 16th century farmhouse where Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines ran the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Portrait of Arthur Lett-Haines’ - Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947)

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arthur Lett-Haines (British,1894 – 1978)

Vue d'une Fenêtre, 1967

Mixed media on paper

260 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arthur Lett-Haines (British,1894 – 1978)

The Dark Horse ,1934

Watercolour, graphite, chalk and gouache on paper

370 notes

·

View notes