#and they even have a small rewilding program

Text

Good News - April 8-14

(Actually 8-12 due to irl obligations)

Like these weekly compilations? Support me on Ko-fi! Also, if you tip me on here or Ko-fi, at the end of the month I'll send you a link to all of the articles I found but didn't use each week - almost double the content! (I'm new to taking tips on here; if it doesn't show me your username or if you have DM's turned off, please send me a screenshot of your payment)

1. Interior Department Finalizes Action to Strengthen Endangered Species Act

“These revisions, which will increase efficiency by reducing the time and cost to develop and negotiate permit applications, will encourage more individuals and companies to engage in conservation benefit agreements and habitat conservation plans, generating greater conservation results overall.”

2. Young Puerto Ricans Restore Habitat Damaged by Hurricane While Launching Conservation Careers

“Corps members help restore the island’s environmental and cultural assets and volunteer in hard-hit local communities. They also gain valuable paid work experience and connections to possible future employers, something many young Puerto Ricans struggle to find.”

3. Australian-born cheetah released in Africa for the first time ever. Watch the heart-warming moment Edie is set free

““The Metapopulation Initiative will bring in appropriate males, probably two initially, to breed with Edie,” King says. “It’s those future cubs, and their cubs, that will ensure the legacy of spreading Edie’s genetics across the southern African metapopulation. And we will have also provided Edie – a wild animal, let’s not forget – with a chance of a life in the wild.””

4. Baby Bald Eagles Confirmed in 2 of 4 Nests in Will County Forest Preserves

“A pair of fuzzy eaglet heads were spotted popping up out of one of the nests this week, officials said. Two weeks ago, monitors noticed adult eagles feeding an unseen hatchling (or hatchlings) in a different nest.”

5. New Hope for Love for Japanese Children Needing Families

“The new system, established by a 2022 law, offers private childcare institutions financing to transform their business model into “Foster Care Support Centers” that recruit, train, select, and support foster parents, and assist the independence of children living in foster families. If a childcare institution becomes a Foster Care Support Center, the government will fund full-time staff members based on the number of foster households they cater to.”

6. Nexamp nabs $520M to build community solar across the US

“Nexamp, a community solar developer and project owner, has secured a whopping $520million to install solar arrays around the nation in one of the largest capital raises to date for this growing sector. Community solar gives renters, small businesses and organizations the chance to benefit from local solar power even if they can’t put panels on their own roofs.”

7. A natural touch for coastal defense: Hybrid solutions which combine nature with common “hard” coastal protection measures may offer more benefits in lower-risk areas

“Common “hard” coastal defenses, like concrete sea walls, might struggle to keep up with increasing climate risks. A new study shows that combining them with nature-based solutions could, in some contexts, create defenses which are better able to adapt.”

8. Rewilding program ships eggs around the world to restore Raja Ampat zebra sharks

“A survey estimated the zebra shark had a population of 20 spread throughout the Raja Ampat archipelago, making the animal functionally extinct in the region. […] Researchers hope to release 500 zebra sharks into the wild within 10 years in an effort to support a large, genetically diverse breeding population.”

9. Forest Loss Plummets in Brazil and Colombia

“New data reveals a decline in primary forest loss in Brazil and Colombia, highlighting the significant impact of environmental reforms in curbing deforestation. According to 2022-2023 data from the University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab and World Resource’s Institute (WRI), primary forests in Brazil experienced a 36 per cent decrease in deforestation under President Inácio Lula da Silva’s leadership, reaching its lowest level since 2015. Colombia nearly halved (by 49 per cent) its forest loss under the administration of President Gustavo Petro Urrego, who has prioritised rural and environmental reform.”

10. New Agreement Paves the Way for Ocelot Reintroduction on Private Lands

“With the safe harbor agreement in place, partners plan to begin developing a source stock of ocelots for reintroduction. Over the next year, they plan to construct an ocelot conservation facility in Kingsville to breed and raise ocelots. Producing the first offspring is expected to take a few years.”

April 1-7 news here | (all credit for images and written material can be found at the source linked; I don’t claim credit for anything but curating.)

#hopepunk#good news#endangered#law#puerto rico#conservation#habitat#australia#cheetah#africa#big cats#bald eagle#birds#eagles#japan#foster care#solar#solar panels#solar energy#solar power#community solar#coastal#ocean#climate#shark#deforestation#rewilding#south america#ocelot#environment

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I rant about this like, once a month, but the fact we live in the internet age and we still have to reinvent the wheel every two seconds is like aaaaaaarrrgh. Every. single. time. there’s a problem you have people trying and failing and hiring ‘consultants’ and trying again and coming up with some bullshit and it’s like MAYBE SOMEONE ELSE SOLVED THIS ALREADY I mean I can’t even. You hear about so much stuff every day - from dolls and fake bus stops for Alzheimer patients to communal gardens and petting zoos that improve students’ performance and wellbeing in retirement homes to a whole hospital floor converted into a series of birthing rooms so we can combine the comfort of a ‘normal’ room with the safety of a hospital environment to bug-friendly street lamps to safe passages for wild life to listening dogs so children learn how to read faster and improve their self-confidence and every single time you hear about stuff like this it’s featured, like, in the ‘fun & unusual’ section of your local newspaper and then it dies there and you have to listen to local politicians and headteachers and doctors and whoever the fuck else devoting hours and hours of brainstorming and experimenting and ‘Oh a growing percentage of kids are shy and can’t read oh my’ and you feel like yelling THERE’S A SCHOOL IN GERMANY THAT USED FUCKING GOLDEN RETRIEVERS LOOK IT UP and then someone else is all ‘Old people are more and more depressed’ and again you’re all THIS ONE PLACE IN BELGIUM CREATED A RABBIT GARDEN and my God, I don’t even know what the problem is? People not having a common language for sure, and also the underlying belief everyone else is just a bit more savage than you so who cares, but still. Fucking enough.

#pet peeve#old woman yells at cloud#thought of the day#rant of the day#problem solving#internet age#smh#wtf#i mean my problem today#is that my town is EXCELLENT with communal gardening#and they even have a small rewilding program#to create a friendlier environment for bees and bugs and stuff#meanwhile the town 20 miles away#just goes at it with a chainsaw#and doesn't give a fuck#like why#better things are not always more expensive??#man i can't even

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

After 604 Years, White Storks are Nesting in Britain Again

Despite their 600-year absence, white storks have remained an important symbol in folklore, children’s stories, on pub and hotel signs, and in family names and nicknames down the centuries.

As part of ongoing efforts to restore nature in the U.K., a project is bringing beloved white storks back to the British countryside.

— July 15, 2020 | National Geographic | By Isabella Tree

A female white stork greets her mate as he brings nesting material to the top of an oak tree at Knepp Estate, in southeastern England. This year, white storks at Knepp became the first of their kind known to have bred in Britain since 1414.

Britain's White Stork Project, which aims to establish 50 breeding pairs by 2030, is part of a wider effort to restore nature.

KNEPP ESTATE, ENGLAND — High in an oak tree in the county of West Sussex, in southeastern England, a pair of free-flying white storks hatched three chicks. It was May 6, 2020, a landmark moment: It had been 604 years since the previous written record of white storks breeding anywhere in Britain. Two weeks after those first chicks emerged at Knepp Estate, another pair of storks, in another shaggy nest of sticks in a nearby oak, hatched three more.

“This achievement is beyond thrilling. We dreamed of this moment, and now the storks have done it—we have British-born chicks again!” says Tim Mackrill, a reintroduction expert with the White Stork Project. Launched in 2016, the project aims to establish 50 breeding pairs of white storks in southern Britain by 2030.

More than three feet tall, with snow-white bodies, black wings spanning seven feet, and long, red legs, white storks often nest on roofs in towns and villages across Europe, where they’re much loved. As spring migrants from wintering grounds in Kenya and Uganda and as far south as South Africa, they’re associated with good luck and rebirth—hence the fairy tale of white storks delivering new-born babies in slings from their beaks. The joyful bill-clattering of a courting pair atop their nest—a resonant knocking made by the rapid opening and closing of their beak, with head thrown back to amplify the sound through their throat pouch—associates white storks with marital tenderness.

No one knows for certain why storks disappeared from Britain, though their appearance on the menus of medieval banquets suggests that they may simply have been targeted for food. Despite their 600-year absence, however, white storks have remained an important symbol, featuring in folklore, children’s stories and illuminated manuscripts, on pub and hotel signs, and in family names and nicknames down the centuries. The White Stork Project hopes that excitement about the return of these charismatic birds will spark greater public interest in nature recovery in the U.K. and, perhaps, pave the way for more species reintroductions.

In recent months, the newcomers at Knepp indeed have been a cause for celebration—a distraction from the gloomy statistics of COVID-19 and a focus of public empathy, their actions even seeming to mirror those of humans under lockdown. At the end of March as people hunkered at home, the white storks began incubating their eggs. In mid-May with travel restrictions to nature areas in the U.K.lifted, the two sets of eggs hatched, allowing hundreds of visitors to see the chicks for themselves.

In the past few days, the first set of chicks have fledged the nest, flying down to the ground to feed on grasshoppers under the watchful eye of their parents and roosting in nearby trees at night. During the coming weeks, just as airline flights begin opening up and people take to the skies once more, the adventurous young storks will fly farther afield, perhaps even following their parents and popping over to Europe for a spell.

Although recent decades have been hard on white storks in Europe, they aren’t endangered. Draining of wetlands, habitat for amphibians and small fish the birds eat, and pesticide-driven absences of insects that supplement their diet, combined with fatalities from collisions with power lines, have led to declines in many parts of Europe. These losses in part have been offset by reintroductions in France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Poland, and Sweden.

Emblems of a Wider Movement

In the U.K.—one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, ranked 189th out of 218 countries, according to a Biodiversity Intactness Index run by the Predicts project—more than two-fifths of mammals, insects, birds, and other wildlife have seen significant declines since the 1970s. White storks are emblematic of a wider movement to repair nature in the country, of which Knepp Estate—run by my husband, Charlie Burrell, and me—is a pioneer.

To kickstart natural processes, in 2000 we began rewilding our 3,500 acres of depleted, loss-making farmland. This hinged on restoring the river, ponds, and wetlands, allowing thorny scrub and trees to regenerate, and introducing free-roaming herbivores such as old English longhorn cattle, Exmoor ponies, and Tamworth pigs as proxies of extinct aurochs, tarpans, and wild boars. Then we stood back and allowed nature to take over.

By browsing, rootling, trampling, wallowing, and dispersing seeds in their dung, these animals have created complex, novel ecosystems, swiftly and with astonishing results. Knepp is now a breeding hot spot for endangered nightingales, turtle doves, and purple emperor butterflies. It’s home to all five species of owls In the U.K. and 13 of the 18 bat species. More than 1,600 insect species have been recorded, many of them nationally rare. All these creatures have found haven at Knepp on their own, attracted by emerging habitats and food resources.

The white storks, however, have needed help to re-establish themselves. Every year, 20 or so of the birds venture to England from Europe, but finding no other storks nesting here, they fly on. Like herons and egrets, white storks nest in colonies for safety in numbers, social learning, and ease of finding a replacement should a mate die. Without this group reassurance, they’re unlikely to attempt to breed.

European reintroduction projects have pioneered a way of mimicking a colony by raising white storks in large pens in open countryside, using non-flying rescue birds and captive-bred birds with clipped wings, to attract wild storks. Eventually, wild birds breed with the captive storks, and their offspring migrate, returning loyally to their natal site. (Read about the resurgance of white storks in France.)

In 2016, the government-approved White Stork Project chose Knepp as its starter site. The project is a partnership among three private landowners and the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, an international charity founded by writer Gerald Durrell to save species from extinction; the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, experts in bird reintroductions across Europe; and Cotswold Wildlife Park, a privately owned zoo in Oxfordshire. Knepp’s biodiverse wetlands and grasslands and open-grown trees for nesting are perfect habitat for storks. (Coincidentally, the name of the village of Storrington, just nine miles from Knepp, is derived from Estorchestone, meaning Abode of the Storks in Saxon English. The village sign features two white storks.) Two other locations—Wadhurst Park Estate, in East Sussex, and Wintershall Estate, in Surrey—were identified for establishing supplementary release pens the following year.

Knepp welcomed the first cohort of 20 juvenile storks donated from Warsaw Zoo, in Poland, into its six-acre pen in December 2016. With them were four non-flying Polish wild adults—birds injured in road accidents or by power-lines—to help instill natural social behavior in the juveniles. This replicates successful reintroductions in Sweden and Alsace, in France, where a breeding program begun in 1976 has seen white stork numbers grow from fewer than 10 mating pairs to more than 600 today.

One of the nesting females at Knepp, a particularly bold five-year-old from the first set of Polish imports, flew to France in 2018, where she spent a year with wild birds before returning to Knepp to pair up with one of the storks in her pen. (We know this because of reported sightings identifying the conspicuous ring-tag on her leg.) Another GPS-tagged juvenile raised at Knepp migrated to Rabat, Morocco, last year and is now in Spain. The male of the other nesting pair is a wild bird, one of several already attracted by the presence of the new colony.

Native or Not?

Not everyone in the U.K. embraces the White Stork Project. Opponents argue that historical evidence for white storks in Britain is slim and that they shouldn’t be considered a native species. Alfred Newton in A Dictionary of Birds, published in 1896, thought the white stork “had never been a native or even inhabitant of this country.”

Moreover, critics say, for this “new” species to attain “native” status, the birds should form colonies on their own, without human involvement. They point to the spontaneous recent arrivals in southeastern England of little egrets and great white egrets. “I would rather…allow natural colonization of our birdlife,” says Lizzie Bruce, director of British Birds magazine. To her, the white stork effort “feels more like a vanity project, especially as the species is of least concern” for conservation triage.

Birders echo that sentiment on social media, saying it would be better to focus not on a flamboyant species that isn’t endangered but on birds, such as the tree sparrow, that are struggling to survive but have less obvious appeal. Some conservationists who worry about the effects white storks might have on habitats or prey species such as insects and amphibians have called for environmental impact studies. This seems an impossible challenge, given the potential extent of the birds’ feeding range in southeastern England, the relatively small number of storks involved, and the variety of their food sources, including earthworms.

None of these criticisms trouble Ian Newton, a former visiting professor of ornithology at the University of Oxford and former senior ornithologist at the Natural Environment Research Council, the U.K.’s leading public funder of environmental science. (Newton is not affiliated with the White Stork Project.) The white stork, he says, is represented in bone remains at the Bronze Age site of Jarlshof, in Shetland; the Iron Age site of Dragonby, in Lincolnshire; the Roman site of Silchester, in Hampshire; and the Saxon site at Westminster Abbey, in London—all from long before the previous written record, in 1416, of white storks nesting in Britain.

“If we restrict ourselves to reintroducing species well-recorded in the historical record, we would exclude from consideration all those species which disappeared earlier but for which Britain still offers suitable habitat,” such as Dalmatian pelicans, night herons, and eagle owls, Newton says. Reintroductions, to his mind, offer not only the joy of seeing lost species return but also great potential for conservation.

“Generally speaking, the more widespread a species within its natural range, the more abundant and secure it is in the longer term,” Newton says, adding that reintroductions of charismatic species attract “an enormous amount of interest and support from the general public. This can benefit local economies and attract money into conservation that would otherwise be spent on other activities.” Further, the storks themselves may bolster other species. In Europe, their gigantic, shaggy nests provide nesting habitats for numerous birds such as starlings and house and tree sparrows.

Knepp’s white storks have already become something of a media phenomenon, with extensive coverage domestically but also by French and Polish TV. More than 2,500 visitors have seen the chicks since COVID-19 restrictions were relaxed, and 20 miles away, a gigantic mural on the city of Brighton’s busy North Road depicts white storks flying in to feed their chicks. The mural, expressing a heightened appreciation for both clean air and nature under lockdown, exhorts us to Let Nature Breathe—a suggestion, perhaps, that the U.K.’s magnificent white storks indeed are heralding new beginnings.

— Editor's note: This story was corrected on July 17, 2020, to say white storks had been gone from Britain for 604 years and that the juvenile that migrated to Morocco in 2019 is now in Spain.

— Isabella Tree is a freelance journalist and author. In 2018, her book Wilding—Returning Nature to Our Farm won the Richard Jefferies Award for Nature Writing and was voted one of the 10 best science books by Smithsonian magazine.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://techcrunchapp.com/after-wolves-rebound-across-us-west-future-up-to-voters-national-news/

After wolves rebound across US West, future up to voters | National News

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, Wyo. (AP) — The saucer-sized footprints in the mud around the bloody, disemboweled bison carcass were unmistakable: wolves.

A pack of 35 named after a nearby promontory, Junction Butte, now were snoozing on a snow-dusted hillside above the carcass. Tourists dressed against the weather watched the pack through spotting scopes from about a mile away.

“Wolves are my main thing. There’s something about their eyes — it’s mystifying,” said Ann Moore, who came from Ohio to fulfill a life-long wish to glimpse the animals.

Such encounters have become daily occurrences in Yellowstone after gray wolves rebounded in parts of the American West with remarkable speed following their reintroduction 25 years ago.

It started with a few dozen wolves brought in crates from Canada to Yellowstone and central Idaho. Others wandered down into northwest Montana. Thriving on big game herds, the population boomed to more than 300 packs comprising some 2,000 wolves, occupying territory that touches six states and stretches from the edge of the Great Plains to the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Now the 2020 election offers an opportunity to jumpstart the wolf’s expansion southward into the heart of the Rocky Mountains. A Colorado ballot initiative would reintroduce wolves on the state’s Western Slope. It comes after the Trump administration on Thursday lifted protections for wolves across most of the U.S., including Colorado, putting their future in the hands of state wildlife agencies.

The Colorado effort, if successful, could fill a significant gap in the species’ historical range, creating a bridge between the Northern Rockies gray wolves and a small Mexican gray wolf population in Arizona and New Mexico.

“Colorado is the mother lode, the final piece,” said Mike Phillips, who led the Yellowstone reintroduction project and now serves in the Montana Senate.

WOLF FEARS IN COLORADO

Yet the prospect of wolves is riling Colorado livestock producers, who see the predators as a threat their forbears vanquished once from the high elevation forests where cattle graze public lands. Hunters worry they’ll decimate herds of elk and deer.

It’s a replay of animosity that broke out a quarter-century ago when federal wildlife officials released the first wolves into Yellowstone. The species had been annihilated across most of the contiguous U.S. in the early 1900s by government-sponsored poisoning, trapping and bounty hunting.

Initiative opponents have seized on sightings of a handful of wolves in recent years in northwestern Colorado as evidence the predator already has arrived and reintroduction isn’t necessary.

“We can live with a few wolves. It’s the massive amount that scares me,” said Janie VanWinkle, a rancher in Mesa County near Grand Junction, Colorado.

VanWinkle’s great grandparents shot wolves up until the early 1940s, she said, when the last wolves in Colorado were killed. The family runs cattle on two promontories with names from that era — Wolf Hill and Dead Horse Point, where VanWinkle said her great grandfather’s horse was killed by wolves while he was fixing a fence.

“I try to relate that to millennials: That would be like someone stealing your car,” she said. “He had to walk home 10, 15 miles in the dark, carrying his saddle, knowing there’s wolves out there. So of course they killed wolves on sight.”

Mesa County’s population has increased more than five-fold since wolves last roamed there, to more than 150,000, and VanWinkle sees little room for the animals among farms in the Colorado River valley and the growing crowds of backcountry recreationists on the Uncompahgre Plateau.

Colorado’s population is approaching 6 million — almost twice as much as Idaho, Montana and Wyoming combined — and is expected to surpass 8 million by 2040.

“Things have changed,” VanWinkle said.

The pack that showed up in northwest Colorado last year is believed to have come from the Northern Rockies through Wyoming, where wolves can be killed at will outside the Yellowstone region.

Even with protections under the Endangered Species Act, thousands of wolves were shot over the past two decades for preying on livestock and, more recently, by hunters.

YELLOWSTONE RECOVERY

But rancor that long defined wolf restoration in the region has faded somewhat since protections were lifted in recent years. Opponents were given the chance to legally hunt wolves, while advocates learned state wildlife officials weren’t bent on eliminating the animals from the landscape as some had feared.

“I’ve got a simple message: It’s not that bad,” said Yellowstone wolf biologist Doug Smith, who with Phillips brought the first wolves into the park in 1995 and has followed their impacts on the landscape perhaps as closely as anyone.

“I got yelled at, at public meetings,” he said. “I got phone calls: ‘They are going to kill all the elk and deer!’ Where are we 25 years in? We still have elk and deer.”

On a cold October morning, after examining remains of the bison eaten by the Junction Butte pack near a park road, Smith asked a co-worker to have the carcass dragged deeper into brush so it wouldn’t attract wolves and other scavengers that could be hit by a vehicle.

Later, as the sun struggled to break through cloud banks, he hiked up a trail in the park’s Lamar River valley to where the first wolves from Canada were released.

The animals initially were kept in a large outdoor pen to adjust to their new surroundings. The pen’s now in disrepair, sections of chain-link fence crushed by fallen trees. But Smith was able to show where wolf pups had once tried to dig their way out , and another spot outside the enclosure where some freed adult wolves had tried to dig back in.

All around were young stands of aspen trees. The area had been overgrazed by elk during the years when wolves and most grizzly bears and cougars were absent — direct evidence, Smith said, of the profound ecological impact from the predators’ return.

EUROPE DEBATES WOLF RETURN

Yellowstone’s experience with wolves has spurred debate among European scientists over whether a gradual comeback of wolves on the continent could also revitalize landscapes there, and be welcomed or at least tolerated by local people, said Frans Schepers, with Rewilding Europe, which works to restore ecosystems in multiple countries. There have been no European wolf reintroductions to date, but land-use changes coupled with fewer hunting and poisoning campaigns have allowed populations to begin rebounding naturally in several countries.

Since 2015, wolf packs that traveled over the Baltics have established three or four packs in the Netherlands and packs in neighboring Germany and Belgium. Government programs provide money for Dutch farmers to erect fences to deter wolves.

In the British Isles, where the last wolves were exterminated in the 1700s, a wilderness reserve in Scotland is seeking permission to bring wolves to about 78 square miles (200 square kilometers) of fenced enclosure to help control a runway deer population and draw tourists.

Alladale Wilderness Reserve owner Paul Lister views Yellowstone, where wolves controlled elk numbers, as a model.

“All the native predators are gone,” Lister said of the Scottish reserve.

THE BALLOT BATTLE

In Colorado, hunting outfitter Dean Billington foresees economic disaster if the 2020 wolf initiative passes. His Kremmling-based Bull Basin Guides & Outfitters is ideally situated for one of the state’s largest trophy elk herds, the White River elk herd. He estimates his firm alone spends more than $250,000 a year for hunting leases on ranches.

“They’re land wealthy and day-to-day poor,” Billington said of ranch owners. “This income keeps the western ranching guys afloat.”

The initiative calls for initially introducing 10 wolves annually by Dec. 31, 2023, with a goal of 250 wolves within a decade.

“You’re putting wolves in my backyard,” Billington said of supporters of the reintroduction initiative. “They say they’ll compensate for lost cattle and sheep, but how would it feel for these people in Denver if their dog in the back yard was mauled to death by the wolf and someone throws a few bucks at you to make you feel better?”

Rob Edward with the Rocky Mountain Wolf Action Fund, the group behind the initiative, sees reintroduction as a national rather than state issue since it involves public lands that account for 70% of western Colorado.

“Colorado’s public lands are diminished without wolves,” he said.

The Yellowstone experience is key to his group’s arguments: Reintroduction restores balance to the ecosystem, improves wildlife habitat and will benefit hunters by thinning out weaker prey.

Standing in the decaying pen where Yellowstone’s wolves got their start, Smith said that if the Colorado reintroduction initiative passes, success ultimately rests more on human tolerance than the animals’ proven biological resiliency.

“Don’t recover wolves unless there’s areas where you can leave them alone,” he said.

———

Anderson reported from Denver and Larson from Washington, D.C..

———

On Twitter follow Brown: @MatthewBrownAP; Anderson: @jandersonAP, and Larson: @larsonchristina

———

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

(function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.7"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

0 notes

Photo

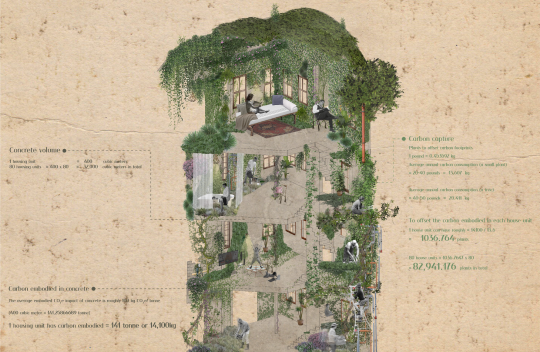

Phase 03: Rewilding vs Controlling

I have found this similar interesting place that is Hanoi Vietnam called “ Lideco village” which is an abandoned village because the area is overpriced in the eye of potential buyers even though the area is located in the capital city.

Moreover, I know that in middle of Hanoi, it has an on-going environmental issues since the government is prioritizing economic growth over the environment. The air quality there is bad and it has lots of non-biodegradable wastes in city due to chemical spills so people don’t rely on local products anymore.

So, my program introduces a new style of architecture “rewilding ” which aims to solve on-going problems in Hanoi; air, waste, noise pollution. Also, create naturally aesthetic of ruin structures for living, at the same time, being a gigantic purifier of Hanoi. This place is like a prototype that is probably going to prevent any worse events from happening or reducing their effects in the future.

Whenever the “rewilding ” structures are ready, the developer will resell them. Now the value is not on shell and core structure anymore but on the fully-grown plants means. In this case, plants become financial asset instead.

Now, I zoom into these processes and the radius of the circle represent timeline. First, looking at the timeline of the core structure or the upper ones. Starting by constructing phase of the abandoned project (or PHASE1) and then it is finished after roughly 5 years (PHASE2). Since the houses were unsalable, the existing bare concrete structures at the Lideco are gradually decaying in 5-7 years without re-treatment, from my research.

At some period, we move to PHASE3 where plants and vines are growing on the microscopic cracks of concrete which is available calcium, nutrient to those plants. And those plants are slightly becoming a structure, help maintaining the old concrete structure and finally taking over some part of that and become a structure themselves. Essentially, my work as an architect starts from this PHASE3. Here in this phase, for the living purpose, I will add some primary functional elements like pipes and infrastructures which will be visible from outside of the walls. The last phase or PHASE4, which should take about 15 years, I plan to focus on maintaining the homegrown plants to keep them in good condition and also install electricity and other necessary furniture to complete the project.

For the lower row, as we wait for the transformation of structures which might be years as it takes time for plants to grow... another essential feature is all the furniture used in this FUTURE Lideco will be the plant itself…. I was thinking about the furniture used in this rewilding project. I planned to grow and shape the trees TO BE our furniture as you can see in the example, I have a tree grow into a chair. This way, we don’t have to cut down the big trees in order to use just tiny pieces of it to make the furniture. The idea is like an ORGANIC 3D printing that has water and sunshine as machines. There is no need of glue, nail, or any man-made joint to hold each piece // and the material is also durable and corresponding to our core value which is sustainability. To clarify, I divided these processes into 3 steps, planting, having a mold for the plants to climb up / and control and maintain them by shaping and bending, finally harvest them once I get the intended shape (to dry and further process it to make it look nice). Depending on how good of weather is, each step will take times about more or less 5 years which should be ready by the time the plant on the core structure is fully-grown and the house is livable.

For the aesthetics of wall, curtain, column, façade will be customizable by choosing from these plants catalog. For example, Ragoon creeper, the pink one at the bottom, which is a type of vine, that aside from its aesthetic beauty, can be used to reduce the level of PM 2.5 in which will help purify the air around the living area. In this case, the plants will replace the use bare concrete to differentiate between each house and become the essential element of the house instead.

The project will also have a pre-selling where the fully rewilding structure and will be available on Airbnb website for any potential buyers to experience the house before making purchasing decision.

At the same time, through these maintained plants, they also help capture embodied carbon in the concrete. So the question becomes... how much plants we need.. to offset those carbon footprints in the concrete...

Here the calculation shows the amount of concrete used in each house unit which is about 400 cubic meters and we have 80 units so it is going to be about thirty-two thousand in total. And from the research, there is 100 kg of carbon embodied in each ton of concrete so 1 housing unit would have about 141 tonne or roughly one hundred and forty thousand kg....

Also, from research, a small plant can offset carbon about 20-40 pound annually or about 14 kg and about 40-50 pounds or about 20 kg for a tree.

So to sum up, I plan to grow around one thousand thirty six plants to offset the embodied carbon in 1 house unit.. and around eighty-two thousand nine hundred forty-one plants for the overall project to offset the whole project’s carbon footprints.

Here, the village will offer a trimming services every 2 weeks for the purpose of control and maintenance in order to maintain a balance between WILD and CONTROLLED when the space is inhabited. As you see from the calculation, the amount of plants I have to grow is really A lot to totally offset the carbon effect.

And, lastly, here is the overall view of Lideco village in the near future that I’m going to improve its aesthetic on existing ruined structures, turning them to a gigantic natural and sustainable purifying green area of Hanoi with zero carbon footprints on structure. Presenting the new modified domestic habitation in the idea of rewilding…

Eventually, an environment that has been abandoned for a while then fulfilled by another financial speculation of trying to resell the building through rewilding. As people move in, this future Lideco will finally be able to fulfill the concept of living , reaching my ultimate manifesto intention.

0 notes

Text

How to Prepare Now for the Complete End of the World

OKANOGAN COUNTY, Wash. — When the end comes, some will not be waiting in a bunker for a savior. They will stride out into the wilderness with confidence, ready to hunt and kill a deer, tan its hide and sleep easily in a hand-built shelter, close by a fire they made from the force of their two palms on a stick.Four hours from the Seattle airport, in a valley called Methow, near a town called Twisp, Lynx Vilden was teaching people how to live in the wild, like we imagine Stone Age people did. Not so they could get better at living in cities, or so they could be better competitors in Silicon Valley or Wall Street.“I don’t want to be teaching people how to survive and then come back to civilization,” Lynx said. “What if we don’t want to come back to civilization?”Some people now are considering what it means to live in a world that could be shut down by a pandemic.But some people are already living like this. Some do it because they just like it. Some do it because they think the end has, in fact, already begun to arrive.

⎌

A couple of times a year, Lynx — she goes by the name professionally, though it is not her legal name — teaches a 10-day introduction to living in the wilderness. When I arrived for this program, Lynx ran to me, buckskins flying, her hands cupped tightly around something that was smoking.She held it toward my face. I closed my eyes and inhaled deeply. Confused, she moved her smoking handful to someone else, who blew on it lightly. It was an ember in a nest of seed fluff. Lynx was making fire.Her property looks like a kidnapper’s lair from a movie. But her dream, she told those of us gathered, is a human preserve. Her vision is called the Settlement. It will have a school, where people can come in street clothes and learn to tan hides. But to enter the preserve itself will mean giving oneself over to it.“You walk into it naked and if you can create from that land what that land has to offer, then you can stay there,” Lynx said. “It’s going be these feral rewilded people. I’m thinking in two to three generations there could be real wild children.”We set up our tents around her property. I had a sleeping bag from high school, a Swiss army knife and a stack of external batteries. It scared me that there was no cellphone reception. We communicated over the week in hoots. One hoot means hoot back. Two hoots means “gather.” Three hoots means an emergency, like near-death level.The class may have been there to go ancient, but they brought very modern food requests. In a group of seven, one student was a strict carnivore — Luke Utah, who likes a morning smoothie of raw milk, liver and egg yolk. Another was a vegan. One student said they were so sensitive to spice that even black pepper was overwhelming. One person was paleo, one was allergic to garlic, and one was gluten-free.Louis Pommier, a French chef turned backpacker, was bartering his skill for attendance. He nodded empathetically as he heard these restrictions but would go on to mostly ignore them. The first night he made a chicken curry.Many of the people who were there came feeling useless in their lives. Some had just quit their jobs. Lynx said many of the students who come for the monthslong intensives (another option) are divorced, or on their way to it. Several talked about feeling embarrassed at how soft their hands were, and how dependent they had gotten on watching TV to fall asleep.

⎌

We woke up the next morning and gathered around the open fire for boiled eggs. Soon we would learn how to chop down a tree. First Lynx greeted the tree. She put her hands on it.“If you’re willing to be cut down, will you give a yes?” she asked. She tugged the tree. She calls it a muscle test. Apparently the tree said yes. “We have to kill to live,” she said.Many students had brought elegant knives and axes from rewilding festivals — there’s a booming primitive festival circuit, with names like Rabbitstick Rendezvous, Hollowtop and Saskatoon Circle — but when confronted with an actual tree they didn’t want to use those. There was an old ax they used instead. Its head periodically flung off, each time narrowly missing someone. The tree eventually fell, a foot from my tent.The vibe was a mix of Burning Man, a Renaissance Fair and an apocalyptic religious fantasy. There was no doomsday prepper gun room — what would happen when bullets run out? Nor was there a sort of kumbaya, gentle-love-of-nature-yoga-class vibe. When Lynx told the story of killing her first deer, she said the deer, wounded, tried to drag herself away.We shaved off the tree’s bark and got to the cambium, the soft inner layer of bark that we would boil in water. This would be used to tan hides. We learned on supermarket salmon skin. We tore into the plastic bags of sockeye salmon with stone shards, then descaled the skin with dull bones.Lynx demonstrated how to process a deer hide using a hump bone from a buffalo. She sent us to go look for bones from the kitchen. Our job was to scrape off the muscle and fat. The hide was heavy, wet and beginning to rot.Sometimes she played a deer leg flute while we worked.That night was bitterly cold. I wore every piece of clothing I brought. Lynx coached us in warming big rocks by the fire, rotating them like potatoes, wrapping them in wool blankets. I heaved my two rocks, too hot to touch, covered in ash, into the sleeping bag with me.“Another thing you can do to make a big cozy bed is just rake a pile of pine needles and just burrow in and put logs on either end so it stays together,” Lynx said.

⎌

Lynx looks like Peter Pan, only 54 and with bone earrings. She is thin and quite beautiful, deeply wrinkled in a way that skin doesn’t usually get anymore. One day she wore red grain-on leather pants and her belt buckle was an elk antler crown. Another day it was a coat made of buffalo. She carried a Danish dagger made of a single piece of flint. On her belt was a little pouch made of bark-tanned salmon skin and deer hide holding a twig toothbrush, a sinew sewing cord and a bone needle, a piece of yerba santa for smudging.She never sat or rested on an object, even to eat. She always crouched. She ate out of a tree burl that she had hollowed into a bowl.Our clothes made a statement. We were not backpackers. No artificial colors, no carabiners and dangling straps and sexless sea foam green fleece. Here we wore tight leather pants. The whole point was to bring our animal selves here, and animal selves should attract mates.One day Lynx wanted us to go to town for groceries. She wore her skins. We smelled disgusting. In town there was a church with a billboard that read, “Alert today, alive tomorrow.” There was a yarn store called Fiber next to an antiques store advertising itself as a nostalgic journey. We wandered down the aisles reeking of rendered, rotted deer fat and smoke.“She’s like a blond-haired blue-eyed dressed up like a North American native person from a century ago, so she’s a striking image that’s easy to capture a lot of people’s attention,” Matt Forkin said. He is a hardware engineer with X, Alphabet’s experimental tech division. He has studied with Lynx, and is also now going in on some land in the Sierra Foothills with friends where they plan to go wild.There are several of these new rewilding compounds emerging. One of the larger efforts is in Western Maine, where a group is working to replicate a hunter-gatherer community. What used to be a handful of bush-craft schools to learn these skills is now an industry of hundreds.On a walk Lynx found some deer scat and handed it out, and a bit of stringy inner bark too, some dead limbs, mullein stalks. I asked what kind of plant a branch is called and she bristled.“Naming something makes people think they know it when they don’t,” Lynx said. “It’s the golden torch light spindle. That’s what it does.”A group of her former students visited with stew, and we sat around a fire. They had two young children in tow, and homemade plum mead. They started just like us, they said. They were city people, mostly from the Bay Area. I visited their enclave the next morning.

⎌

Down a dirt road, past ramshackle cabins and horses, one group of permanently rewilding people have set up a series of yurts and shelters.Epona Heathen, 33, used to have a different name and used to live in Oakland, Calif., working at a thrift store. She felt the call to wilderness while studying sociology at University of California, Berkeley.“I’m writing this paper and the chair is wobbly, and I don’t know how to fix it,” Epona said of her time in the urban world. “I’m eating eggplant, and I don’t know where it grows.”“One day I was like, ‘This is crap. We live month to month. We spend all our money on booze and coffee. We can’t save like this. We can’t live like this. We all talk about getting back to earth, but we did know anything about it.’”After some time on organic farms, they found Lynx. They decided to stay for a six-month Stone Age immersion.“We had to come with 15 tanned hides and five pounds of dried fruit and five pounds of dried meat,” she said.Her partner Alex, who is 31 and who worked at a grocery store as a wine specialist, bought a property nearby. Now about a dozen young people live there.Epona’s yurt is 16 feet around and 12 feet tall, with a small wood-burning stove. She built curved bookshelves along the wall. Most of her food and medicine is dried in jars. There is a cat named Kitty and a dog named Arrow. She identifies as an animist.“People say, ‘Oh when the apocalypse comes. …’ What are you talking about? It’s here. I’m a collapsist,” she said. “I’m not invested in maintaining the comforts we have.”The Heathens, as the group named themselves, sometimes calls the cities they came from Babylon, all the same, all fallen.The biggest challenge, they’ve agreed, is that no one around them is old.“Most of us are in our 20s and early 30s,” Epona said. “You start to see where the holes in society are, and our holes now are elders.”That night, Alex took a horse over the mountain to visit some friends, while Epona stayed behind to host. She made deer, squash, and root vegetables stew. They had vats of plum mead and got the sauna going.There are enough people on the hill for a variety of love triangles. Epona and Alex split. Now Epona is dating a young woman on the property.Alex grew up in Montclair, N.J., and inherited some money. He is bald, muscular and tattooed. He said he used to be more dogmatic about living primitive, but that is changing.“I just moved out of my yurt and into a house,” he said. “I got a second truck.”Roxanne, who is 26 and has bright curly red hair, was here for community, she said. She was working alongside Alex, rubbing salt into hides. She just moved a couple weeks ago and had been working at a coffee shop before this.“You know, the thing about living the dream is it’s really hard!” she shouted, hauling another salt bag.There is a main house down the hill, with a land line that everyone shares. The place is decorated in skulls and massive birds. There is a buffalo strung out to dry outside and a tall stack of deer legs at the door. More fit and dusty young people lounged inside. They were roasting a deer leg.A sense of collapse underlies their opposition.“From a purely rational engineering mind looking at the trends in the data, exponent times an exponent, our utilization of natural resources is way beyond the natural carrying capacity of the earth, and we’re seeing that in essentially ecosystem collapse,” Matt Forkin had told me. “In our lifetimes there is a very high chance we will see major social collapse. I do think there will come a time when these skills are practical for a large number of people.”Alex made a gesture toward the small town over the hill and down the road. “Everyone is partying their final days away,” he said.Lynx was padding around in wool in her little cottage at the end of the property. She sleeps indoors in the winter. Her home is all exposed wood and overflowing planters, horns and old rattles. She was prickly and suspicious, upset that I had left her property to visit the Heathens.Her daughter, Klara, lives in Washington, D.C. Klara’s boyfriend works for the World Bank.“When I met him,” Lynx said, “my first question was, ‘Do you hunt?’ No. ‘Do you chop wood?’ He said, ‘I could try.’”Lynx is single, and that is starting to bother her.“The hard part is finding a partner to share it with,” Lynx said. “Maybe I’m getting to the point where people get fixed in their environments.”She had a traditional childhood with traditional parents in London but left at 17 to play music. She moved to Sweden, went to art school. One day she met a man and they moved to Washington State to backpack. She went into the woods.For a while, she was married to a man named Ocean. They had Klara. She home-schooled her in the mountains in Montana, but Klara went to live with Ocean. Lynx went farther into the wilderness.But even she cannot escape money, yet. A week-long class costs $600. “I have to have my foot in two worlds to maintain some semblance of how I want to live in this world,” she said. Klara answers email for Lynx.In September, Lynx will lead another fully Stone Age project, marching into the nearby public lands. All clothes must be handmade, all food gathered.Lynx’s family still lives in London, mostly. Her sister is a freelance conservator.

⎌

We imagine that someone striking out into the wilderness is doing so to get away from everyone, to be alone. The people I met wanted the opposite. They want a life where they cannot survive even a day alone. They cannot get food alone, cannot go to the bathroom, cannot get warm alone. They want to be dependent.“The city is actually the place of rugged individualism,” said my classmate Joan, who grew up in suburban Philadelphia and uses the pronoun they. “Here I’m using my hands and with people all day.”Before being in the wild, they were addicted to video games and loved social media; very soon, Joan said, they were going to smash their smartphone. They were wearing a thick vest they had felted, with a full marten, body and head, sewn in as a collar for warmth.“Some people don’t get it, but I prefer this life,” Joan said. “No, I don’t use toilet paper. I use moss and I like it better.”Together, in the wild, everyone had to soften. One night, one of the guys said something offensive about gender roles, and a couple of us got annoyed. Then we all had to stop arguing because there was no one else to be with. I started arguing about politics with someone. Instead of going away, he had cold contraband beer, and I had nothing better to do than learn more about him. My only entertainment was the people around me. It made them more interesting.“Really coming back to nature means responding to the social responsibility too. Someone says you have this personality flaw, you can’t just avoid them. You have to respond. You adapt,” Epona said. “Rugged individualism is a lie. Rugged individualism cannot survive.”“There’s a social skill set of working in a community,” Luke Utah said.At one point, I got separated from the group. There was nothing I could do. I checked the river. I checked the houses. I checked the little pine needle burrows where people sometimes slept. I hooted once. I hooted twice. I sat and waited in a terror while it got dark.Our time makes social obligation largely unnecessary. When I moved apartments, I hired TaskRabbits. When I got cold, I turned on the heat. In the woods, the evening entertainment I got was what we could provide one another. Now, suddenly, I did not want to be alone for a minute. The dependence felt amazing. I shrieked with joy when the group came jaunting back.The next time I went to town, I dreaded the spasms of my phone wriggling back to life. I could feel the reception in the air, could feel being alone again. I was relieved to cross over the hill, out of service and back again to Lynx and my friends.Deer legs are very useful. Their toe bones can be whistles and buckles and fish hooks. The leg bones become knives and flutes. Tendons become glue. I popped the black toes off into boiling water. Slicing with obsidian, I peeled the fur off and then the muscle and tendons. I sawed the ends off the bone. I used a twig to oust the marrow. The carnivore ate it. This would be my flute.

Read the full article

#1technews#0financetechnology#03technologysolutions#057technology#0dbtechnology#0gtechnology#1technologycourtpullenvale#1technologydr#1technologydrive#1technologydrivepeabodyma#1technologydriveswedesboronj08085#1technologyplace#1technologyplacerocklandma#1/0technologycorp#2technologydrive#2technologydrivestauntonva24401#2technologydrivewarana#2technologydrivewestboroughma01581#2technologyfeaturestopreventcounterfeiting#2technologyplace#2technologyplacemacquarie#2technologywaynorwoodma#3technologybetsgenpact#3technologycircuithallam#3technologydrive#3technologydrivemilpitasca95035#3technologydrivepeabodyma#3technologydrivewestboroughmassachusetts01581#3technologyltd#3technologyplace

0 notes

Text

Expert: It’s time for us as a people to come together, to form an understanding about our natural environment, and our connection to it. If we are to survive long into this century and beyond, our society will have to learn to re-indigenize itself. This will be a painful process for those dependent on creature comforts, on the electrical grid’s continuous power supply, on the streams of TV, Netflix, even the internet itself, on factory-made pharmaceuticals, etc. It will be difficult for those whose illusions are about to be shattered, for those who thought they could live for so long and have it so good at the expense of others and to the detriment of their natural, wild surroundings. We aren’t going anywhere. There will be no moon and Mars colonies to flee to. Isn’t it suspicious, though, how little talk there is about the parallels between the past colonialists of North America and the sci-fi dream of future colonies in space? Any potential future space colony wouldn’t be a glitzy affair: it would be similar to past and present immigrants and refugees streaming across continents, trying to escape death, privation, despair. In short, the dream of human habitation of the solar system exists because of the utter destruction of landscapes and the indecency of human societies in many parts of our planet. Imagine if we actually decided to collectively care for our own world instead of having day-dreams and wasting billions on rockets and gadgets to propel us towards the “final frontier”. Doesn’t that sound nice? Luckily for us, the resiliency of our planet towards habitat degradation is very, very strong. That is why a policy of rewilding must be introduced into mainstream thinking and politics. Coined by David Foreman, rewilding refers to conservation methods that strengthen and maintain wildlife corridors and large-scale wilderness areas, with an emphasis placed on carnivores and keystone species which act as linchpins for ecosystem stability. Rewilding leads to increased connectedness across previously fragmented habitat due to roads, railways, urban sprawl, etc. In the Americas, please consider educating yourself and others about these issues, and donating to a few of the fine organizations promoting wildlife corridors, such as: the Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, the Paseo del Jaguar program led by Panthera, and the American Prairie Reserve. Strengthening our ecosystems will provide a higher quality of life for future generations, as well as your children and grandchildren. Now that’s a return on investment. Forget about yourself, your fragile ego, and your “standards of living”, for a moment. Western capitalism and colonialism has been degrading habitats for centuries, with benefits mostly accruing to white, older men. Only by giving back to the land, and in many cases, non-intervening and letting our soils and waterways heal on their own, will allow for a more equal distribution of wealth. It is natural resources, not money, which are the real inheritance we will leave behind to our youth. The distribution of the “common-wealth”, by the way, used to be far more equitable hundreds of years ago, when land was freely available for hunting, fishing, foraging, and farming. Yes, there is less abject poverty in Europe and the US today compared to centuries ago, but it has come at a steep cost: there is no self-reliance, no collectively and culturally stored traditions of farming, crafts, weaving, pottery, home-building. Corporations have swallowed all this, citing the “need” for specialized divisions of labor. Self-sufficiency and homesteading are looked upon with scorn, and we are told to buy everything we could ever need (and desire), instead of co-producing tools, clothes, food, and more. Sharing of community resources needs to be re-instilled in the populace. The average garage, shed, or extra closet of today’s Westerner is filled with useless crap used maybe a few times a year, all purchased from a few companies. Recycling usable equipment and renting for small fees throughout the communities will significantly decrease consumption and foster closer neighborhood ties. Today, the legal webs and labyrinths of “property laws” and low-wage work have imprisoned the average person. So has the spread of capitalism and unequal distribution of money, division of labor, separation of classes. The lives of masses of working people, the precariat, are just as unstable and misery-inducing as they were centuries ago, when Frederick Douglas said: Experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and rushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other. This all underscores the need for rewilding the American people, not simply expanding our National Forests and wildlife refuges. It calls for a transformation in consciousness, to promote understanding of different cultures, openness towards change, and advocating for compassion and peace. We can begin by starting to support a 15 dollar wage, to fight for climate science funding, to promote renewable energy. Yet there needs to be an understanding that those actions, while a good start, are simply a few first baby-steps towards re-orienting our culture. Ultimately, the longing for spiritual rejuvenation and community empowerment will break through the cage of modernity, if we are not first destroyed by ecological devastation and/or economic collapse. Longing, in all actuality, is too mild a term; actually, there is an intense craving for unique and authentic notions of identity, for belonging to a caring culture, for sharing and cultural blending. There is also, to an extent, evolutionary reasons and epigenetic possibilities for the deep desires, for instance, to want to sing and dance around a fire, to go on long walks to calm the mind, to talk to plants and animals, to feel the Earth’s joys and pains, to partake of psychedelic plants. It’s what our species has done for millennia, and no freeways, high-rises, fluorescent-lit malls, or gated communities can possibly make up for these urges. Inner calmness and contentedness, feeling joy at other’s successes, altruistic actions of bravery, spontaneity, the creative act, and trans-personal experiences all teach us that our egos are illusions. The drive of the ego is the drive of civilization, with all its life-denying baggage. It is this ego-based desire to dominate, to harness and pillage nature, which expands outwards to include all life-forms, including even our close loved ones. The judgments and pain inflicted on others are projections of our own, deep inner hurting. The ego shifts the blame, projecting, always outwards onto others, always disguising and rationalizing its selfish deeds. Indigenous life is not without problems, but it recognizes and integrates the shadow-side of ourselves: there was no need for modern psychology until modern, Western man ramped up the process of destroying the world, all in order to fill the gaping void within the soul. Thus, rewilding our psyches will mean dissolving the ego, recognizing it as a small part of the mind, occasionally useful in survival-enhancing or problem solving situations, but not as an absolute master of our sense of self. In short, it must be acknowledged that there are many aspects to individual minds, spectrums of ways of thinking, just as specific brain-waves exist, and differing states of sleep and dreaming. Shrinking the ego will re-establish our commitment to protecting the Earth. As creator and protector of life, our planet, along with crops, animals, mountains and rivers, all have been venerated and deified across history. Thus, the sacredness of life and its continuity can be seen for the miracle it truly is. New spiritual and religious groups will be founded, with cross-fertilization and syncretism causing an explosion of kaleidoscopic cultures. Shrinking petty individual desires and grievances enlarges our view of nature: it allows for free living and amicable relations, promoting an idea of an Unconquerable World which can triumph over the capitalist-dominated, chaotic, absolutist, totalitarian impulses of modern life. This has serious implications. What cannot be used; i.e., extra physical products, food, and extra income must be given away to less fortunate countries. Open-source medicine and technology will have to be distributed to developing nations to stave off the worst symptoms of global warming and habitat degradation. In the wealthy West, the rich should look to the example of the indigenous, where in some tribes the chieftains distributed their personal wealth among their tribe, often to be rewarded in kind at a later ceremonial/seasonal time of the year. Companies that produce weapons or various useless waste will be forced to shut down. Education will be reoriented to focus on the potentialities of each individual student, not as a one-size-fits-all indoctrination mill, churning out damaged, submissive, domesticated youth. Green constitutions will have to be drafted to provide regulations to protect humans and wildlife from unnecessary pollution and production. It’s not just the West that will lead: the Chinese must realize, and be planning for, the eventuality that the demand for crappy plastic goods and gadgetry at big-box stores is going to decline, worldwide, in the coming decades. A new international order based on the UN, or otherwise, will be needed to uphold climate change commitments, speedily develop renewable energy tech, sustainable agriculture plans, and distribution of resources. Basically, this requires a shift from an anthropocentric outlook to an ecocentric outlook. This will require a global awakening, and a moral/spiritual transformation of consciousness. It is the only way for our societies to move forward. Adaptability and having a broad range of skills and a wider knowledge base will be preferred over the narrow, technological elitism we see today in the corporate world and reflected in culture and the media. Ultimately, rewilding ourselves means learning how to live free; i.e., unlearning what our consumer-based culture has brainwashed us into believing. I don’t intend to shy away from the hard political questions of what the world and the US could look like in the near future, if the above steps are taken. Most likely, the modern nation-state will perish, America included. Our national experiment has been blood-drenched and steeped in genocide, slavery, domination by capitalists, and structural racism from the very beginning. A new era of cooperation is called for, with true democratic consensus and citizen involvement in governance as well as the workplace. Smaller areas based on bioregionalism and the city-state will replace the nation-state (which Gore Vidal, among others, spoke out in favor of) and will be more likely to prosper, as they will be more likely to provide for their citizens. Climate refugees and nomadic ways of life will increase for those fleeing disaster, or simply seeking better opportunities. Decentralization of power as well as a closer connection to the land will foster a reawakening of the tribal ways of life, where tight-knit communities care for the sick, the elderly, disabled, and troubled souls, instead of shunting them into various soul-crushing institutions like jail, mental hospitals, etc. A new era of solidarity and care for the meek must begin. This will mean feeding the millions per year who die of starvation, drought, lack of medical care, etc. This will mean reprioritizing our lives, with no excuses. Radical egalitarianism and faith in the boundless potential of each and every person must be instilled in our societies. Some will denounce this as radical, utopian, unachievable. Those who say so are without hope, without faith, having been indoctrinated by mainstream media and enshackled by capitalist ideology. Recently, in an interview, China Mieville explained this quite well: We underestimate at our peril the kind of onslaught of received opinion from the media, from the sort of cultural establishment, basically kind of ruling out of court any notion of fundamental change. Ridiculing it as ridiculous, to the extent that, you know, when you start to talk about wanting a better world you see the eyes rolling. What kind of despicable pass have we come to, that that aspiration raises scorn? And yet that’s where we are, for huge numbers of the political establishment. What sort of ideology can replace this cynicism, this nihilism? What kind of world do we want to create? I defer to Carl Rogers: Let me summarize my own political ideology, if you will, in a very few words. I find that for myself, I am most satisfied politically when every person is helped to become aware of his or her own power and strength; when each person participates fully and responsibly in every decision which affects him or her; when group members learn that the sharing of power is more satisfying than endeavoring to use power to control others; when the group finds ways of making decisions which accommodate the needs and desires of each person; when every person of the group is aware of the consequences of a decision on its members and on the external world; when each person enforces the group decision through self-control of his or her own behavior; when each person feels increasingly empowered and strengthened; and when each person and the group as a whole is flexible, open to change, and regards previous decisions as being always open for reconsideration.1 * May, Rollo, et al. Politics and Innocence: A Humanistic Debate. Saybrook Publishers, 1986. http://clubof.info/

0 notes