#and because people only know punitive extreme forms of 'justice' that seems to be the only frame of reference they have...

Text

I think a lot of people don't support punitive justice on a governmental level (good), but they don't understand why punitive justice is overarchingly a bad thing, so they still operate with the idea that it's still the Best Option, but only when they can wield it.

Of course, there is a difference between a government having access to punitive justice and individuals or a small community having access to it, but the mindset is still strikingly similar. I've seen it time and time again where one's desire to destroy after even a small slight outweighs anything else, and that's alarming, actually. Yes, it's understandable, but I still don't think it is a healthy impulse or knee-jerk reaction for every minor affront.

#politics#i'm sure i talked about this before but it still strikes me as important#how exactly will everybody be helped by using the absolute extremes of 'justice'?#and because people only know punitive extreme forms of 'justice' that seems to be the only frame of reference they have...#...so when somebody proposes other methods of justice it is seen not unlike abuse or assault apologia or something extreme...#...because the nuance isn't there to recognize levels of severity in an action where punitive justice isn't going to work#and i'd argue that people are generally more invested in the perpetrator/s of abuse rather than the victims/survivors left in their wake#so people frame the discussion as Protecting Victims as a Class but really#ARE you helping us? and if so - what are you doing beyond going After Our Abuser/s?#people think it helps us to Go After The Abuser/s. much less do they think about *us* as people and what we need i think.#maybe its selfish of me but i know my abuser will never face any repercussions beyond people judging them slightly for what they did to me..#...so me personally i would rather people take their fury with my abuser (in my real life) and maybe invest it in myself and others...#...maybe hell will be waiting with open arms for them when they die. but i'm still going through hell because of them so i feel it's even#maybe i've just ~given up~ but i want to help people rather than immediately going After People#not everything CAN be solved with an eye for an eye. not everything SHOULD.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tragedy of “The Wrong Jedi”

The first time I watched the Jedi Temple bombing arc in Star Wars: The Clone Wars, I was kind of uncomfortable with how it played out. I felt like it misrepresented how the Jedi Council would have handled the situation, that Anakin was going too far and uncomfortably close to the Dark Side, and that Ventress was handled strangely. But after reading a whole bunch of posts by tumblr user gffa and others about how the Jedi didn’t handle it too terribly, I’ve had to rethink my view. Thinking about it more, it’s definitely even more tragic than I realized.

I’ve got a lot to say (seriously, a massive wall of text) and, even though this is a really old show, I might as well put spoilers under the cut.

Okay, first of all: Ahsoka might not have been found innocent if she stayed in jail, but I bet she would. Barriss knocked out the guards and left Ahsoka a keycard to break out of her jail cell. As soon as she used it to break out, Ahsoka fell into the trap. If she’d just sat in the cell, eventually order would have been restored in the prison, and there would have been some sort of evidence that someone else was trying to frame her. Unless Barriss managed to spin it so it looked like Ahsoka broke out, killed some clones, and then returned to her jail cell? Seems unlikely. The genius of the trap was that breaking her out was exactly the sort of rule-breaking she’d expect Anakin to do, so I can’t blame her for falling for it.

Actually, taking a step back, the frame-job only worked because Ahsoka was an impulsive Padawan. I tried imagining how other Jedi would have reacted, and a few of them would have ended up much better. Anakin probably would have been screwed too, but a lot of more-experienced Jedi would have just begun meditating calmly in the cell and been able to follow the promptings of the Force to end up with a better outcome. In particular, Obi-Wan probably would have laughed about the key card and managed to talk his way to some sort of advantage with the clones who came to investigate. (And, of course, someone like Yoda might have just sensed Barriss like Tarkin said Ahsoka should have been able to.) None of this is Ahsoka’s fault, of course--she’s a great Jedi; she’s just in training still, and not the calmest.

Moving on, the Jedi Council expelling Ahsoka *really* bothered me, and I don’t think that’s an uncommon opinion. Other people (gffa, again) have talked at length about how they were under great pressure from the Senate, and so it wasn’t entirely their fault, but I still thought it was a terrible, if understandable, decision. They brought that the Senate was concerned they wouldn’t be impartial, but I thought, “Let the Senate be concerned. The Council *know* they’re impartial, so if Padawan Tano is guilty, they’ll find her guilty and punish her. Which, of course, is what the Senate wants. And if she’s innocent, they should support her no matter the political consequences.” But then I realized that the evidence against her was so strong at that point that the Council was probably assuming any trial would find her guilty, and the only real point of contention would be the punishment. The Jedi would probably decide on a punishment that wasn’t strong enough for the Senate’s liking. So instead, they decided that expelling her from the order *was* their punishment. It’s my opinion that this was either discussed in offscreen Council deliberations or just understood by the Councilmembers, who’ve worked together for a long time. The episode probably just didn’t make this explicitly clear because we’re intended to emotionally be on Ahsoka’s side, feeling betrayed like her, and only figure out the larger implications later with more thought and analysis. If this is true, it totally worked on me. You could definitely make a good argument that they still should have made a stand, but with public opinion and the opinion of the Senate turning against them, they had to pick and choose their battles.

THE TRIAL

The real thing that convinced me to write this post was the emotions and framing of the end of the trial, when Anakin brings Barriss forth and gets her to confess. The whole trial makes masterful use of oppositions. First, Tarkin and Padme are prosecutor and defender. They literally enter from opposite sides. Symbolically, since we know these characters, this is Grand Moff Tarkin supporting his vision of punitive control (he calls for the death penalty!) versus Senator Padme Amidala, supporting the rights and freedoms of an innocent. The symbolism and conservation of characters is nice enough that I can overlook how stupid it is that an Admiral and a Senator are the ones arguing this case or that the Chancellor of the Republic is also overseeing a trial. (Also, a Jedi accused of sedition is a BIG DEAL.)

Palpatine, of course, gives a grand speech about how Separatists have fooled the Republic before, laying on the irony as thick as he can as he accuses Ahsoka of being part of a plot to tear the Jedi Order apart. There’s an interesting interaction when Anakin breaks his stride right before he declares Ahsoka guilty, and I imagine he was torn between annoyance and his desire to have Anakin like him. And then when Barriss starts her big speech about how the Jedi have lost their way, he must be thrilled that these sentiments are getting such traction among the populace that even a Jedi espouses them and gets such a public stage to proclaim them.

Because--and this is the important part--Barriss is WRONG.

- “The Jedi are the ones responsible for this war.” -- INCORRECT

- “We have so lost our way that we have become villains in this conflict.”--INCORRECT. One thing that bothered me is that so much of the anti-Jedi argument is that they’re killers, but we almost always see them fighting droids. This is the most bloodless war ever, even assuming there’s a ton of offscreen collateral damage. ONSCREEN we see the Jedi avoiding collateral damage as much as possible.

- “We are the ones that should be put on trial; all of us.”--No, literally just Barriss should be put on trial, for her senseless crimes.

- “My attack on the Temple was an attack on what the Jedi have become--an army fighting for the dark side.”-- Incorrect on two counts. Others have explained how the Jedi are CLEARLY the good guys in this show, and more than that, her attack on the Temple was pointless murder that failed to even make a clear statement. She killed Jedi, non-Jedi workers, and clones, so I guess she was just symbolically opposing the war effort, but considering she had to explain herself before anyone guessed her motives, I don’t think she did a very good job.

Once you accept that Barriss is wrong, this becomes extremely tragic.

- Anakin’s clearly struggled with the dark side over this whole arc, but he hasn’t Fallen. He’s still firmly a Jedi, firmly rooted in the Light. He lets Ventress go when he realizes she’s not responsible (which may have been a bad decision ethically, but it was probably better than just killing her), tries talking calmly to Barriss first, and sees justice done. He works within the system by making sure Ahsoka is arrested.

- The music is just SO GOOD. When I was believing Barriss, the dark, dramatic music just made me more uncomfortable (”ahh, the bad guy is right?!”), but now it’s just sad.

- This trial has been taking place in a Senate courtroom with the Imperial logo prominently displayed on the wall, Tarkin prosecuting, and the future Emperor presiding. But when justice is truly served, it’s by Anakin Skywalker, a Jedi Knight opposing Palpatine, and four Jedi Guardians escorting a prisoner. And...look, in terms of iconography, those guys are awesome enough to challenge all the Imperial paraphernalia, with their masks, armor, and special yellow lightsabers. Seriously, I’m surprised over the strength of the feelings I’m having about the clash of icons here. The failing Republic/future Empire is about to perpetrate a great injustice, but in march the traditional guards of an ancient peacekeeping order in full dramatic procession to bring true justice.

Barriss and everyone else taken in by anti-Jedi propaganda fail to realize that the Jedi aren’t the cause of the problem--they’re just a bandage struggling to help people like Padme hold a failing Republic together as crime syndicates, the Sith, and more base forms of evil such as corruption tear it apart.

I’ve written waaaay too much already, so I won’t talk about it too much, but Ahsoka’s arc in season 7 supports my thoughts. Basically, that arc starts with her realizing how the common people often have at least semi-legitimate reasons to dislike the Jedi, and it ends with her realizing that she’s been acting like a Jedi the whole time (and the one hostile Martinez sister realizing that since Ahsoka’s basically a Jedi, she’s been judging the Jedi too harshly).

#star wars#sw the clone wars#in defense of the jedi#the wrong jedi#the jedi who knew too much#to catch a jedi

33 notes

·

View notes

Link

I have been thinking, like so many people this week, about rage. Who I’m mad at, what that anger’s good for, how what makes me maddest is the way the madness has long gone unrespected, even by those who have relied on it for their gains.

For as long as I have been a cogent adult, and actually before that, I have watched people devote their lives, their furious energies, to fighting against the steady, merciless, punitive erosion of reproductive rights. And I have watched as politicians — not just on the right, but members of my own party — and the writers and pundits who cover them, treat reproductive rights and justice advocates as if they were fantasists enacting dystopian fiction.

This week, the most aggressive abortion bans since Roe v. Wade swept through states, explicitly designed to challenge and ultimately reverse Roe at the Supreme Court level. With them has come the dawning of a broad realization — a clear, bright, detailed vision of what’s at stake, and what’s ahead. (If not, yet, full comprehension of the harm that has already been done).

As it comes into view, I am of course livid at the Republican Party that has been working toward this for decades. These right-wing ghouls — who fulminate idiotically about how women could still be allowed to get abortions before they know they are pregnant (Alabama’s Clyde Chambliss) or try to legislate the medically impossible removal of ectopic pregnancy and reimplantation into the uterus (Ohio’s John Becker) — are the stuff of unimaginably gothic horror. Ever since Roe was decided in 1973, conservatives have been laboring to roll back abortion access, with absolutely zero knowlege of or interest in how reproduction works. And all the while, those who have been trying to sound the alarm have been shooed off as silly hysterics.

Which is why I am almost as mad at many on the left, theoretically on the side of reproductive rights and justice, who have refused, somehow, to see this coming or act aggressively to forestall it. I have no small amount of rage stored for those in the Democratic Party who have relied on the engaged fury of voters committed to reproductive autonomy to elect them, at the same time that they have treated the efforts of activists trying to stave off this future as inconvenient irritants.

This includes, of course, the Democrats (notably Joe Biden) who long supported the Hyde Amendment, the legislative rider that has barred the use of federal insurance programs from paying for abortion, making reproductive health care inaccessible to poor women since 1976. During health-care reform, Barack Obama referred to Hyde as a “tradition” and questions of abortion access as “a distraction.” I’ve spent my life listening to Democrats call abortion a niche issue — and worse, one that is somehow repellent to voters, even though support for Roe is in fact among the most broadly popular positions of the Democratic Party; seven in ten Americans want abortion to remain legal, even in conservative states.

You can try to tell these Democrats this — lots of people have been trying to tell them for a while now — but it won’t matter; they will only explain to you (a furious person) that they (calm, wise, knowledgeable about politics) understand that we need a big tent and can’t have a litmus test and please be reasonable: we shouldn’t shut anyone out because of a difference on one issue. (That one issue that we shouldn’t shut people out because of is always abortion). Every single time Democrats come up with a new strategy to win purple and red areas, it is the same strategy: hey, let’s jettison abortion! (If you object to this, you will be told you are standing in the way of the greater progressive project).

I grew up in Pennsylvania, governed by anti-abortion Democrat Bob Casey Sr.; his son Bob Jr. is Pennsylvania’s senior senator now, and though he’s getting better on abortion, Jr. voted, in 2015 and 2018, for 20-week abortion bans. Maybe my rage stems from being raised with this particularly grim perspective on Democratic politics: dynasties of white men united in their dedication to restricting women’s bodily autonomy, but they’re Democrats so who else are you going to vote for? Which reminds me of Dan Lipinski, the virulently anti-abortion Democratic congressman — whose anti-abortion dad held his seat before him. The current DCCC leader, Cheri Bustos, is holding a big-dollar fundraiser for Lipinski’s reelection campaign, even though it’s 2019 and abortion is being banned and providers threatened with more jail time than rapists and there is someone else to vote for: Lipinski is being challenged in a primary by pro-choice progressive Democrat Marie Newman. And still, Bustos, a powerful woman and Democratic leader, is helping anti-choice Lipinski keep his seat for an eighth term. So I’ve been thinking about that part of my anger too.

Also about how, for years, I’ve listened to Democratic politicians distance themselves from abortion by calling it tragic and insisting it should be rare, instead of simply acknowledging it to be a crucial, legal cornerstone of comprehensive health care for women, people with uteruses, and their families. I have seethed as generations of Democrats have argued that if we could just get past abortion and focus instead on economic issues, we’d be better off. They never seem to get that abortion is an economic issue, and that what they think of as economic issues — from wages and health care to housing and education policy — are at the very heart of the reproductive justice movement, which understands access to abortion to be one (pivotal!) part of a far broader set of circumstances that determine if, when, under what circumstances, and with what resources human beings might have and raise children.

And no, of course it’s not just Democrats I’m mad at. It’s the pundits who approach abortion law as armchair coaches. I can’t do better in my fury on this front than the legal writer Scott Lemieux, who in 2007 wrote ablistering rundown of all the legal and political wags, including Ben Wittes and Jeffrey Rosen and Richard Cohen and William Saletan, then making arguments, some too cute by half, about how Roe was ultimately bad for abortion rights and for Democrats. Some like to cite an oft-distorted opinion put forth by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who has said that she wished the basis on which Roe was decided had included a more robust defense of women’s equality. Retroactive strategic chin-stroking about Roe is mostly moot, given the decades of intervening cases and that the fight against abortion is not about process but about the conviction that women should not control their own reproduction. It is also true that Ginsburg has been doing the work of aggressively defending reproductive rights for decades, while these pundits have treated them as a parlor game. As Lemieux put it then, it was unsurprising, “given the extent to which affluent men safely ensconced in liberal urban centers dominate the liberal pundit class,” that the arguments put forth, “greatly understate or ignore the stark class and geographic inequites in abortion access that would inevitably manifest themselves in a post-Roe world.”

Or, for that matter, that had already manifested themselves in a Roe world.

Because long before these new bans — which will meet years of legal challenge before they are enacted — abortion had grown ever less accessible to segments of America, though not the segments that the affluent men (and women) who write about and practice politics tend to emerge from. But yes, thanks to Hyde and the TRAP laws and the closed clinics and the long travel distances and paucity of providers and the economically untenable waiting periods, legions of women have already suffered, died, had children against their will, while columnists and political consultants have bantered about the necessity of Roe, and litmus tests and big tents. In vast portions of this country, Roe might as well not exist already.

And still those who are mad about, have been driven mad by, these injustices have been told that their fury is baseless, fictional, made of chewing gum and recycled copies of Our Bodies Ourselves. Last summer, the day before Anthony Kennedy announced his resignation from the Supreme Court, CNN host Brian Stelter tweeted, in response to a liberal activist, “We are not ‘a few steps from The Handmaids’ Tale.’ I don’t think this kind of fear-mongering helps anybody.” When protesters shouted at Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings a few weeks later, knowing full well what was about to happen and what it portended for Roe, Senator Ben Sasse condescended and lied to them, claiming that there have been “screaming protesters saying ‘women are going to die’ at every hearing for decades” and suggesting that this response was a form of “hysteria.”

It was the kind of dishonesty — issued from on high, from one of those Republicans who has inexplicably earned a reputation for being “reasonable” and “smart,” and who has enormous power over our future — that makes you want to pull the hair from your head and go screaming through the streets except someone would just tell you you were being hysterical.

And so here we are, the thing is happening and no one can pretend otherwise; it is not a game or a drill and those for whom the consequences — long real for millions whose warnings and peril have gone unheeded — are only now coming into focus want to know: what can be done?

First, never again let anyone tell you that the fury or determination to fight on this account is invalid, inappropriate, or inconvenient to a broader message. Consider that this is also what women and marginalized people are told all the time about their anger in general: that they should not express it, not let it out, because to give voice to their rage will distract from their aims, undermine them; that it will ultimately be bad for them. This messaging is strategic. It is designed to get angry people to keep their mouths shut. Because if they are successfully stifled, they will remain at the margins, isolated, alone in their fury. It is only if they start letting it out and acting on it and working in tandem with others who share their outrage that they might begin to form networks, coalitions, the building blocks of movements; it is when the anger is let loose that the organizing happens in earnest.

Second, seek the organizing that is already underway. In the days since this new round of state abortion bans have begun to pass and make headlines, secret Facebook groups have begun to form, in which freshly furious women have begun to talk of forming networks that would help patients evade barriers to access. Yet these organizations already exist, are founded and run by women of color, have long been transporting those in need of reproductive care to the facilities where they can get it; they are woefully underfunded. The trick is not to start something new, but to join forces with those who have long been angry about reproductive injustice.

“Abortion funds have been sounding the alarm for decades,” said Yamani Hernandez, who runs the National Network or Abortion Funds, which includes 76 local funds in 41 states, each of them helping women who face barriers getting the abortion care they need, offering money, transportation, housing, and help with logistics. Only 29 of the funds have paid staff; the rest are volunteer-run and led with average budget sizes of $75,000, according to Hernandez, who said that in 2017, 150,000 people called abortion funds for help — a number up from 100,000 in 2015, thanks to the barrage of restrictions that have made it so much harder for so many more people. With just $4 million to work with, the funds were able to help 29,000 of them last year: giving abortion funds money and time will directly help people who need it. Distinguishing the work of abortion funds from the policy fights in state houses and at the capitols, Hernandez said, “whatever happens in Washington, and changes in the future, women need to get care today.”

And whatever comes next, she said, it’s the people who have been doing this work for years who are likely to be best prepared to deal with the harm inflicted, which is a good place for the newly enraged to start. “If and when Roe is abolished,” said Hernandez, “the people who are going to be getting people to the care they need are those who have largely been navigating this already and are already well suited for the logistical challenges.”

The fights on the ground might be the most current and urgent in human terms, but there is also energy to be put into policy fights. In 2015, California Congresswoman Barbara Lee authored the EACH Woman Act, the first serious congressional challenge to the Hyde Amendment, which came after years of agitation and activism, especially by All Above All, a grassroots organization led by women of color and determined to make abortion accessible to everyone. Those who are looking for policy fights to lean into can call and write your representatives and candidates and demand that they support the EACH Woman Act.

Rage works. It takes time and numbers and a willingness to express it, but it is among the most reliable catalysts of social and political change. That’s the story of how grassroots activism can compel Barbara Lee to compel her caucus to take on Hyde. Her willingness to tackle it, and the righteous outrage of those who are driven to end the harm it does to poor women and women of color, in turn helped to compel Hillary Clinton to come out against Hyde in her 2016 primary campaign; opposition to Hyde is now — for the first time since it was passed in 1976 — a part of the Democratic Party’s platform.

In these past two years, fury at a Trump administration and at the Republican Party has driven electoral activism. And at the end of 2018, the Guttmacher Institute reported that 2018 was the first year since at least 2000 in which the number of state policies enacted to expand or protectabortion rights and access, and contraceptive access, outnumbered the number of state restrictions. Why? Because growing realization of what was at stake — and resulting anger and activism, pressure applied to state legislatures — led representatives to act.

Of course: vote.

Vote, as they say, as if your life depended on it, because it does, but more importantly: other people’s lives depend on it. And between voting, consider where to aim your anger in ways that will influence election outcomes: educate yourself about local races and policy proposals, as well as the history of the reproductive rights and reproductive-justice movements. Get engaged not just on a presidential level — please God, not just at a presidential level — but with the fights for state legislative power, in congressional and senate elections, all of which shape abortion policy and the judiciary, and the voting rights on which every other kind of freedom hinges. Knock doors, register voters, give to and volunteer with the organizations that are working to fightvoter suppression and redistricting and expand the electorate; as well as to those recruiting and training progressive candidates, especially women and women of color, especially young and first-time candidates, to run for elected office.

You can also protest, go to rallies. Join a local political group where your rage will likely be shared with others.

Above all, do not let defeat or despair take you, and do not let anyone tell you that your anger is misplaced or silly or in vain, or that it is anything other than urgent and motivating. It may be terrifying — it is terrifying. But this — the fury and the fight it must fuel — is going to last the rest of our lives and we must get comfortable using our rage as central to the work ahead.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Zero Tolerance Policy Is A Direct Pipeline to Prison

Alexeya Hatfield

April 30. 2021

Sexuality and Nationalism

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Zero Tolerance Policy Is A Direct Pipeline to Prison

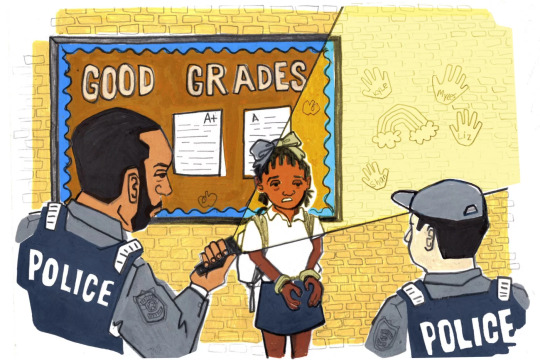

With children appearing equally in the classroom and in the judicial system, there has to be a problem that lead to the sad reality. Children being forced to face the harsh ways of life before their time, with a zero tolerance policy looming over their head in school. Police in schools enforce the zero tolerance policy and help to give out the harshest of punishments for small moments of misbehavior at a faster rate than ever before. The punishments for misbehaving in school has passed the lines of ISS (In School Suspension) or detention, the punishments are passed to the authority of law enforcement. The problem lies in the obvious mistreatment of children of color within the system or punishments. To have children facing criminal charges with a records under their belt before the age of 18 is a dangerously harsh consequence for a mistake. By having a zero tolerance policy with the enforcement of police in school, the school is setting these children of color up for a life of crime and misfortune.

What is the School-to-Prison Pipeline?

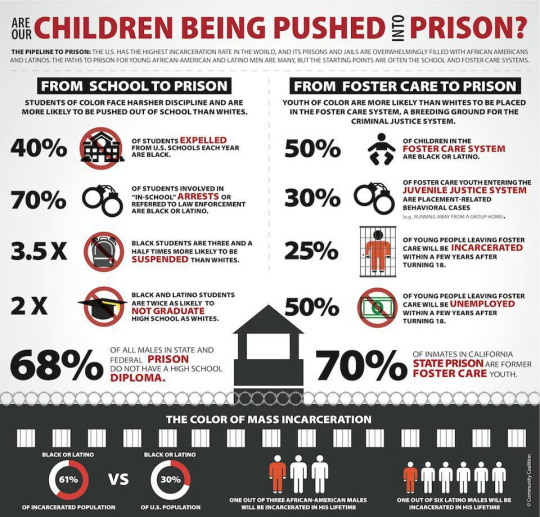

In the United States, due to increasingly stringent school and municipal policies, the term "school-to-prison pipeline" is used to describe the active trend of disadvantaged minors and young people being imprisoned. The school-to-prison pipeline is a process through which students are pushed out of schools and into prisons. In other words, it is a process of criminalizing youth that is carried out by disciplinary policies and practices within schools that put students into contact with law enforcement. (Nicki Lisa Cole, Ph.D.)

Hundreds of school districts across the country have adopted disciplinary policies to drive students out of class at an alarming rate. Children who are transferred from public schools to the juvenile and criminal justice systems often meet the following characteristics: many people have learning disabilities, they may be identified as LGBTQ, and they may have a history of poverty, abuse, or neglect. All these people will benefit from additional educational help, some tutoring and some slower workflows, and consulting services, this may include counseling or classroom adjustments. A classroom to fit their needs with teachers that can patiently give them the attention and help they need. Instead, they were isolated, punished, and released from school to the harsh world to find their way without guidance. “When a school allows a School Resource Officer to arrest a student — or, less drastically and more commonly, refers a student to law enforcement or juvenile court as a form of discipline — they're turning that student over to the juvenile justice system.” (Nelson&Lind)

Researchers have identified three major contributors that help fuel the school-to-prison pipeline:

Zero Tolerance Policies

Implicit Bias

Police in Schools

The Zero Tolerance Policy

The "zero tolerance" policy criminalizes minor violations of school rules, while school police criminalize behavior that should be handled within the school with simple enforcement. Over the past two decades, school suspensions across the country have surged, mainly because schools rely on these policies and punishments. School has become more about authority than about the children learning and evolving in life. The teachers feeling less need to have patience with children who may cause disruption has led to more disciplinary strikes than ever before. When students are kicked out of the classroom for suspension or expulsion, as a result, they are usually referred to law enforcement for formal processing quickly after.

In 1997, 79% of schools across the country had implemented a zero-tolerance policy. With no rules that restricts which teachers can discipline which students, the number of suspensions can only increase. With no rules that restricts which teachers can discipline which students, the number of suspensions can only increase. Teachers that students have never met can send them to the principal’s office for whatever reason. This doesn’t include the racially charged actions adults may take against kids they dislike. By 2000, more than 3 million children were suspended from school each year, the same number of students who will graduate in all public schools. (Hage, 2015) The numbers have only climbed since then with no stopping in sight.

With this in mind, more and more studies have shown that students who miss a lot of class time will return to the classroom where work is lagging behind, confused about what they missed, and are more likely to show it. Without supervision during the day and without any constructive work, they are more likely to be arrested, go to jail or eventually drop out of school. “In the last decade, the punitive and overzealous tools and approaches of the modern criminal justice system have seeped into our schools, serving to remove children from mainstream educational

environments and funnel them onto a one-way path toward prison….The School-to-Prison Pipeline is one of the most urgent challenges in education today.” (NAACP 2005) Too far behind in school, separated from peers, and feeling dejected about life, the student turns to whoever will give them attention and a sense of importance. The zero tolerance policy becomes the go to for whatever situation would lead kids to be kicked out. The numbers continued to grow after the numbers calculated in 2000 when Los Angeles banned the practice of kicking students out of school for subjective infractions like “willful defiance” in 2013.

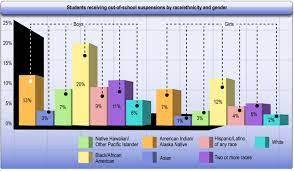

Research also shows that punishments like in school and out of school suspensions and expulsions are disproportionately served out to black students. They are three times more likely than their white peers to be suspended and even more likely to be expelled or referred to law enforcement for the same infractions, according to civil rights data from the U.S. Department of Education. (Hager) The same action that a black child would get a charge for by an officer, a white child would get a detention for. The racially charged abuse against children of color is active in most of the problems they will face in school.

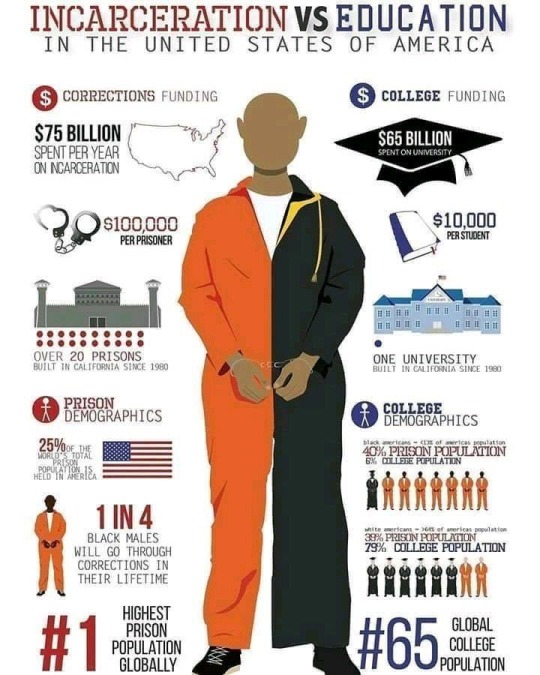

The media representation of young children of color, especially black children does nothing to help the idea that people hold against these children. TV news coverage on black children has referenced them as animals and crazy people who need to be detained and controlled. They only know drugs, violence, and crime so you have to watch them carefully, and this is how people look at them even today. The disadvantage of this is extreme with 1 out of 4 black males experiencing time in corrections in their lifetimes. The current imprisonment rate in the United States is the highest in the world. Over 2.4 Millions of people are held in state or federal prisons and prisons. (PEW 2008)

Recognizing this problem, in 2010, public schools in Boston began to block suspension and expulsion after 743 violations. Within two years of this restriction on suspensions and expulsions, their cases dropped to 120. In 2013, Los Angeles prohibited the practice of kicking students out of school through subjective violations such as "intentional disobedience." The term being too open of a boundary based on opinion and not factual actions of misbehavior. The suspension there has also dropped by more than 50%. (Hager, 2015).

Looking into the background of the children we can find that black youth are at additional risk due to the high rates of imprisonment for African American adults, which can also be traced back to the school to prison pipeline in many situations. Among those born in 1990, one in four black children had a father in prison by age 14. (Wildeman 2009) While young black children represent about 17 percent of the nation‘s youth, they now account for more than 50% of the children in foster care, the reflection of a system that has let them down on many levels. They have less support at home and paired with the rapidly decreasing support at school, they have nowhere to turn.

Police in Schools

Does having police in schools help the children? This is a hard question when including America’s past of school shootings and bullying extremists. Though it is a tough question the number of officers in schools continues to grow steadily, against studies that show less policing would be a better help. (Quinlan 2016) It seems obvious to a point that more suspensions lead to poorer grades which can lead to dropping out of school. The more suspensions you get, the more behind you get, and after a point it will become almost impossible to catch up. If the teacher has to catch a kid up on a month of work while also teaching all their students new things, the situation starts to affect more than that one child. Students who experience the highest rates of in school and out of school suspensions and expulsions in school are, more often than not, black and latino children. Children with disabilities are close behind black and latino children. It can also see in research that officers are more likely to get involved in the discipline of black students than any other student.

At least two-thirds of American high school students attend a school with 1 or more police officers, according to the Urban Institute, and the more children of color in the school, the more police officers are on duty at that school. The national uprising for racial justice in the last few years has led to a push for schools to remove police officers from security and authoritative positions within the school grounds. In 43 states and the District of Columbia, Black students are more likely to be arrested than other students while at school, according to an analysis by the Education Week Research Center.

Suspended students are more likely than non-suspended students to repeat a grade or drop out. The Texas study, which is widely regarded as the most thorough examination of school discipline practices and their consequences, looked into data from every seventh-grader in the state in 2000, 2001, and 2002. They then followed their academic and disciplinary history for six years, discovering that 31% of students who were suspended from school or expelled, only 5% did not fall into this category.

The Obama administration, when in office, launched an investigation into the human rights ramifications of school disciplinary practices, urging schools to restructure their processes so that dismissal and detention are only seen as a last resort. However, several school districts were taking action before and when the Obama administration released the guideline. Many of America's biggest schools are attempting to change the way schools are structured and children receive their education. This is so that students are not sent to the police, or both, in order to punish students in ways other than detention. This will give kids more time in the classroom to learn, more time around their peers to find themselves, and less of a chance to be around bad influences and illegal activities. In Clayton County here in Georgia, for example, the referrals from schools were overwhelming the juvenile prosecutors, so the juvenile courts made an agreement with the police force and the school district. The deal was to set rules that restrict the cases in which police were allowed to arrest students in school or refer them to court. The impact in schools was a steady increase in the number of graduates from high school. The high-school graduation rate increased by 24 percent from 2004 to 2010, beating the national average.

In the meantime, several major school districts are abandoning zero-tolerance laws. Broward County, Florida, one of the country's major school districts, announced in 2013 that nonviolent misdemeanors must be dealt with by schools rather than the police. Chicago Public Schools are attempting to decrease the number of suspensions by, among other things, softening a disciplinary rule that allows students to be disqualified for using a mobile phone in school. They also eliminated suspensions for children who are grades lower than 2nd. After police issued 552 citations to preteens during the 2013- 2014 school year, police in Los Angeles are no longer allowed to report children under the age of 13 to the cops for minor crimes. The punishments and discrimination have no boundaries of age when they are a child of color, so even as some schools implement these rules many still are as young as 7, second grade.

Sandra Trappen breaks down how the system treats these children of color in the system and how it leads to imprisonment and illegal behavior. She goes on to say that the system needs to be restored and calls it, “Restorative Justice” with 6 main points that need to be followed. She suggest that we:

“

Increase the use of positive behavior interventions and supports.

Compile annual reports on the total number of disciplinary actions that push students out of the classroom based on gender, race and ability.

Create agreements with police departments and court systems to limit arrests at school and the use of restraints, such as mace and handcuffs.

Provide simple explanations of infractions and prescribed responses in the student code of conduct to ensure fairness.

Create appropriate limits on the use of law enforcement in public schools.

Train teachers on the use of positive behavior support for at-risk students.”

This restorative system seems to be the only way to build a new and better school system. The money made from a person in prison is not worth the lives of millions. This pipeline affects not only the students but also all school workers, the other students, the police department, and even the prisoners already serving time. The overwhelming numbers make the prisons full which leads to bad sanitation, the teachers have to try and teach them all they missed, the police departments have to deal with the large number of school tickets and normal crime rates, and the other students have to move in fear. It’s more of a negative result than the positive that it was implemented to be. The behavior of the elders in schools, police included, can affect the way all the children grow up to think and feel about authority and the police. It is never a situation that is left in that classroom and has no effect. These environments can affect these childrens for the rest of their lives. In a time where the world is full of evil, racism, and negativity, a school should be a peaceful place to learn and learn about yourself with your peers. Everything else that has been added on has only shifted the gears in the main point of a school system. The primary goal should always be the further the lives of your students to grow and have a good life. America is in need of a change and this small, but huge restorative justice plan would lead to the new beginning that is needed for children everywhere.

Sources

“When School Feels Like Jail,” by Eli Hager, 2015.

“What’s Wrong With the Way Schools Use Police Officers?” by Casey Quinlan, 2016

“A Generation Later: What We’ve Learned About Zero Tolerance in Schools.” Vera Institute Policy Brief, 2013

“The School-to-Prison Pipeline” by Sandra Trappen, 2018.

“The school to prison pipeline, explained” by Libby Nelson & Dara Lind, 2015

―Education Or Incarceration: Zero Tolerance Policies And The School To

Prison Pipeline” by Nancy A. Heitzeg, 2009.

“Why There's A Push To Get Police Out Of Schools” by Anya Kamenetz

“Black Students More Likely to Be Arrested at School” By Evie Blad & Alex Harwin, 2017

“The prevalence of police officers in US schools” by Constance A. Lindsay, 2018

NAACP. 2005. Interrupting the School to Prison Pipe-line. Washington DC.

Word count: 2,500 ( 10 pages in Word, 12pt font and double spaced)

0 notes

Text

The Rule of Law Is for Controlling Power, Not Keeping Order

Many Americans on the political right appeal to the idea of the rule of law to justify expelling undocumented immigrants and preventing ostensibly irregular refugee entry, like the “caravan” from Honduras. The broad idea seems to be that even those in dire need who are seeking the aid of the United States must do so through formal legal channels. For example, Tyler Houlton, the Department of Homeland Security spokesperson, said this on Twitter:

Stopping the caravan is not just about national security or preventing crime, it is also about national sovereignty and the rule of law. Those who seek to come to America must do so the right and legal way.

— Tyler Q. Houlton (@SpoxDHS) October 23, 2018

Similarly, Ari Fleischer declares that “[o]pposition to the caravan… is about the rule of law and people taking advantage of our country.”

This story is infuriating. And so off-base.

Opposition to the caravan, it says, is stoked by fear. To me, it’s about the rule of law and people taking advantage of our country.

https://t.co/580xf6OSNE

— Ari Fleischer (@AriFleischer) October 28, 2018

This is a serious mistake. The point of the rule of law is to control the abuse of power—, particularly government power—not to force the powerless to submit to formal legal processes.

What is the rule of law, anyway?

At its heart, the rule of law is a moral principle of how government power is to be used. It specifies that government power may be invoked:

only when authorized by law,

pursuant to legal procedures that give the people subject to government authority the ability to demand a justification for official action,

and on the basis of laws that reflect a public purpose which treats people as equals.

The classic contrast to “the rule of law” is “the rule of men:” the arbitrary use of the powers of governance by petty autocrats and kleptocrats, the show trials and secret police of the Soviet Union, the disappearances of Pinochet, the shameless plunders of Roman imperial governors, and the roaming gangs of semi-official thugs of Papa Doc Duvalier and Rodrigo Duerte.

Commentators like Houlton and Fleischer don’t just get to invoke their own version of the rule of law. It has a real meaning. When we appeal to the notion of the rule of law, we draw on a long history of thought by lawyers and philosophers about controlling the dangers of lawless government power.

Probably the first reference to anything reasonably translatable as “the rule of law” was in Aristotle’s Politics. For Aristotle, the rule of law was a necessary part of a regime in which the people were understood as equals: if all were equal, then it was wrong for some to have the power to rule others. Aristotle argued that in such a regime, officials were to be understood merely as servants of the law.

A.V. Dicey, usually considered the greatest expositor of the British rule of law, expresses the ideal in a couple of key principles. First, nobody can be punished by the government except pursuant to a violation of law prosecuted via ordinary legal process. Second, nobody is above the law—officials, aristocrats, all are subject to the same law as everyone else.

The canonical documents of our shared legal tradition are filled with Dicey’s principles. Chapter 39 of Magna Carta declares that “[n]o free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against him or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution protect legal equality and forbid life, liberty, and property from being taken by the government absent due process of law.

The great thinkers of this rule of law tradition have also explained why we ought to value the rule of law, understood this way. For Aristotle, as I said, it was a consequence of equality: if the people of a country were genuinely equals, then no one could have the power to rule over others without law.

For F.A. Hayek, the rule of law was about liberty. Hayek argued that a person who could not be punished except according to law could, by consulting the law, have notice of the complete set of forbidden behaviors—giving him or her some guarantee that any other behavior would be permissible. By contrast, someone who could be punished pursuant to the arbitrary will of some petty dictator would have to walk around on pins and needles, afraid to take any bold action for fear of offending the powerful—a phenomenon that free speech scholars call a “chilling effect.” In addition, if officials had to be subject to the same law as ordinary people, they had an incentive to keep that law from being too oppressive—if they made all kinds of silly rules, they burdened themselves like they burdened everyone else. (I have some problems with Hayek’s argument, but they’re not pertinent here.)

Notice how all of this so far has been about the government and its power. Those who fought to establish the rule of law throughout history have always feared the arbitrary use of the monopoly of violence held by states, never the misbehavior of ordinary people. They realized that ordinary people simply didn’t have armies of heavily armed people to do their bidding, and are therefore less of a threat than the state.

The danger of bad rule of law arguments

Yet the American conversation has sometimes featured a troubling second story, according to which this normative principle we call “rule of law” requires ordinary people to obey the law. As the paragraphs above suggest, I think this is a bad mistake—we might call it the obedience mistake. I’ve argued against it at greater length in the academic journals. Taken to an extreme, this kind of talk about the abuse of rule of law actually enables rather than inhibits the overuse of official power.

Nathan Robinson has written a wonderful essay about the absurdity of pretending that a five-year-old immigrant can be held to a document which she signed waiving a right to a hearing—as if the formal rules and signifiers of legal waivers mean anything in the face of the grotesque power disparity between a team of heavily armed federal agents and a toddler. But the obedience mistake almost seems to justify holding the five-year-old to her signature. After all, there’s a formal sense in which it’s just ordinary legal process. The government has the legal power to ask people to waive their rights, and she signed it—in this country, whether at the used car dealership or in the immigration detention, we hold people responsible for the things they sign. If we demand that the government obey the paperwork that formalizes the legal rules established to control its choices, why shouldn’t we make the same demand of those whom the government regulates?

Of course, we all know that’s nonsense. The legal as well as conceptual absurdity of the notion is self-evident here, because a five-year-old doesn’t have the capacity to knowingly and intelligently waive legal rights. Under any even remotely plausible reading of the legal formalities, the document was a nullity from the moment the ink was dry. As it turns out, we don’t let kindergarteners buy used cars either—and not just because they don’t get a license until they’re sixteen.

But what about an adult? Suppose a grown person from Honduras, maybe not so fluent in English, and under pressure (but not illegal pressure) from ICE, signs this document? Must we hold him or her to it as strictly as we’d hold the government to a waiver of its rights?

Or suppose—as doubtless happens every day in the nation’s courts—an innocent criminal defendant agrees to a plea bargain under pressure from the prosecutor. Again, not illegal pressure, as such. Just…pressure. It turns out that America has a lot of really punitive laws, and prosecutors have nearly unconstrained power to [over-]charge people with violating them. Even if you’re innocent, if the prosecutor can charge you with enough crimes to be facing a 20-year sentence, and then they offer you six months, you have to be pretty confident about your ability to convince the jury to risk a trial. So you take the deal. Is this the rule of law?

The rule of law is a one-way street

Here’s one thing that someone might say about the rule of law and these kinds of rights waivers: “we have to respect legal formalities, because the alternative is just to give officials broad discretion: would you rather the rule be that ICE agents get a choice whether or not to give someone a hearing, regardless of what form that person signed or declined to sign?” My imaginary interlocutor might go further, and say that holding government officials to the rules necessarily implies giving legal significance to the individual decisions of people as to whether or not to waive their rights. The choice available to government officials is to strictly follow the law (including holding people to their waivers) or to use their own discretion (and hence have uncontrolled power). There’s no in-between.

Tempting as that thought is, it’s wrong. It’s possible to have one-way discretion. Formally speaking, the rule that “you have to give someone a hearing, unless they sign the paper waiving the hearing” does not entail “if they sign the paper waiving the hearing, you don’t have to give them a hearing.” (To infer the latter from the former would be to commit the classical fallacy of denying the antecedent).

In terms of how we ought to think about discretion and justice, we can and should say that the official does not have the discretion to use the government’s power against the individual when it isn’t authorized by the rules, but does have the discretion to decline to use that power when it is so authorized. Of course, there are some cases, as when the official uses discretion in a biased or self-interested way—never prosecuting people of a particular race or people who pay a bribe—when other rule of law values prohibit the use of discretion. But in most cases we can distinguish between corrupt uses of discretion and the use of discretion to serve justice.

Moreover, sometimes we think that officials ought to exercise discretion to not use their power over people. Suppose a police officer pulls someone over for a minor speeding offense, and then sees a pregnant woman going through labor in the passenger seat. Not only would we praise the officer for letting the driver go, I think most of us would go so far as to say that the officer does something wrong to write the ticket. In such a situation, we ought to describe the use of the government’s power to write the ticket as legally permissible yet unjustified.

The same goes for punitive responses to the caravan. The legality of the prospective actions of caravan members is, at best, complicated. As I understand it, the following three propositions express the legal status of people in the caravan (and I’m not an immigration lawyer, but I’ve run this by some friends who are immigration lawyers, so there’s that):

People in the caravan can show up at ports of entry and request asylum without breaking any U.S. laws at all.

People in the caravan can enter illegally (in which case, obviously, they do break a law), but they’ll be protected from deportation while an asylum request is adjudicated, as well as win the permission to stay in the country if their request for asylum is granted.

U.S. law arguably only entitles people to request asylum when they’re in the country (although another good reading of the statute is that people are entitled to request asylum outside the country, at a port of entry). In principle, Trump could close the ports of entry and make no officials available outside the country for members of the caravan to request entry. Practically speaking, that would mean that in order to make a request for asylum, people in the caravan would have to commit an illegal entry, just to find someone to make the request to. In effect, Trump can set it up so that you have to risk breaking the law in order to seek asylum in the U.S.

So suppose that last contingency happens: Trump closes the border, anyone who asks for asylum has to illegally sneak in to do so.

Improper entry is a relatively minor crime. Shutting down the border is like intentionally closing a major thoroughfare in a big city to force traffic onto side streets knowing in advance that many drivers many will exceed the residential speed limits. That’s irresponsible governance. Still, it’s better if drivers stay within the limits of law. But if they don’t, it’s not a crisis. An increase in moving violations doesn’t call into question the integrity of the legal order.

Likewise, we’re not going to lose anything that we value in the rule of law just because a few people cross the border illegally. Actually, closing the border would be far more irresponsible than shutting down a freeway, because the government would have no purpose for doing so other than to force otherwise innocent people into lawbreaking in order that they might have an opportunity to make lawful claims to asylum that they would otherwise be able to make. It’s analogous less to innocent road construction and more to Chris Christie’s malicious bridge blockade.

The U.S. government has the legal obligation to entertain requests for asylum no matter how the requesters get across the border to make them, and the humanitarian obligation to exercise discretion to allow the requesters to make asylum requests at the border. People like Houlton and Fleischer should stop pretending that it would somehow offend the rule of law for the government to comply with those obligations, even if the requesters do end up having to break the law to get in a position to make the request.

Law and order

Let’s be a bit more charitable to Houlton and Fleischer. There’s surely some reason for people to follow established procedures. If you can enter the country the bureaucratic way, by filling out the forms and waiting at an embassy for a visa, shouldn’t you do so?

I think what Houlton and Fleischer are really getting at, and what a lot of conservative-inclined folks really mean when they talk about the “rule of law” as a reason for people to check the bureaucratic boxes, is something like “order.” And, to be sure, order matters. It’s easier to live in society if your fellow humans behave predictably, as set out by the rules. If nothing else, predictable behavior makes it cheaper to run institutions affecting large numbers of people. And of course violent disorder is unacceptable because violence is morally reprehensible.

But it’s hard to see how nonviolent kinds of rule-breaking are bad other than for those two reasons, that is, because it’s more expensive to deal with disorderly behavior, or because disorderly people sometimes jump queues in an unfair way. Those are the only ways in which rule-breaking even arguably hurts one’s fellow humans.

If that’s what matters to you, that’s fine and good, but you should say so explicitly. Let’s rewrite that Houlton tweet a bit:

Stopping the caravan is not just about national security or preventing crime, it is also about national sovereignty, efficiency, and turn-taking. Those who seek to come to America must do so the inexpensive and bureaucratically-convenient-for-the-government way.

Sounds a lot less convincing, doesn’t it? Traditional rule of law values like freedom and equality might outweigh the humanitarian needs presented by a caravan of refugees—but saving a few administrative costs sure doesn’t.

At most, maybe Houlton can say that it’s unfair to other people who want to request asylum to give priority to considering the requests of those in the caravan—but that argument is implausible too, since we ought to allocate our request-consideration resources according to need, and it’s hard to believe that people who weren’t in dire need would walk thousands of miles to get to a country they perceive as safe. And, at any rate, if we accept that people who are genuinely entitled to asylum under our law are also entitled to request asylum, then if there are more people requesting than our current institutions can accommodate, we ought to spend a little money to expand the capacity of those institutions.

At bottom, this rule of law argument against the caravan seems to come down to nothing but stinginess.

—

Paul Gowder is Associate Professor of Law at the University of Iowa, where he also holds courtesy appointments in the Departments of Political Science and Philosophy. He is author of The Rule of Law in the Real World.

The post The Rule of Law Is for Controlling Power, Not Keeping Order appeared first on Niskanen Center.

from nicholemhearn digest https://niskanencenter.org/blog/the-rule-of-law-is-for-controlling-power-not-keeping-order/

0 notes