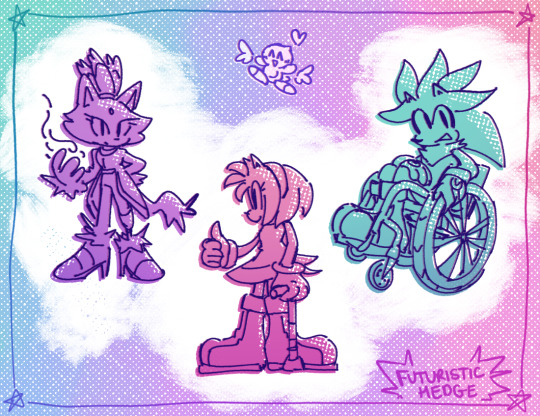

#amy having a cane that transforms into her hammer is something that i think would be so fitting for her

Text

Disability headcanons

#sth#sth fanart#blaze the cat#amy rose#silver the hedgehog#sonic fanart#my art#doodles#sonic disability headcanons#blaze#amy#silver#amy having a cane that transforms into her hammer is something that i think would be so fitting for her#one day ill do a masterpost with all my headcanons but for now you all just get to see snippets here and there#not that my headcanons are all that consistent anyway LOL but! Fun to imagine

753 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claes Oldenburg Is (Still) Changing What Art Looks Like

New Post has been published on http://usnewsaggregator.com/claes-oldenburg-is-still-changing-what-art-looks-like/

Claes Oldenburg Is (Still) Changing What Art Looks Like

Yet when compared to the ice-cold irony of Warhol’s silkscreens or the colorful exuberance of paintings by James Rosenquist, Tom Wesselmann or Rosalyn Drexler, Oldenburg’s work, especially his enduring innovation — rendering sculpture literally soft, through re-creations of everyday things (ice cream cones, typewriters, toilets) that sag from the wall or bag on the floor — looked, and still look, like marvelous reprobates. In the Pop room of any museum gallery, they smirk and slouch and revel in playing at art, seeming to be both the comedians and the clinical depressives.

The latter half of his career, after he grew restless with the art world and moved into cartoonish public sculpture, collaborating with his second wife, the art historian Coosje van Bruggen (who died in 2009), has somewhat obscured his outré spirit — in part because many of the outdoor works, funny and toylike, have become so civically beloved. “Spoonbridge and Cherry,” a red cherry balanced on an enormous spoon, made in steel and aluminum and installed in 1988 in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, is among the most photographed artworks in America, the backdrop for untold thousands of silly selfies. Its fans would likely blanch to learn that among Oldenburg’s early public-art proposals was an idea even creepier than the hole: speakers that would have broadcast a piercing nightly scream through the streets of Manhattan at 2 a.m. As he wrote in one of the lesser-quoted passages from his most famous piece of writing, 1961’s half-satirical manifesto “I Am For …”: “I am for the art that comes up in fogs from sewer holes in winter. I am for the art that splits when you step on a frozen puddle. I am for the worm’s art inside the apple.”

Photo

Oldenburg working out in his studio. Behind him is the work “Big Tools (Screwdriver, Pliers, Hammer),” 1985. Credit Pieter Hugo

THESE WORDS in mind, you don’t fully expect what greets you when you walk into the studio and home Oldenburg has kept on the still-gritty far west side of SoHo since 1971, a five-story warehouse where naval propellers were once manufactured. Inside, it’s as immaculate and organized as a museum. Surfaces gleam and light falls beautifully on the maquettes for public sculpture that line the walls. Slim in khakis and tennis shoes, Oldenburg was sitting in one of the large office spaces with an assistant and wasn’t able to get up to greet me. A fall last year broke his hip, forcing him to get around with a cane or by propelling himself across the floors on rolling office chairs. His daughter, Maartje Oldenburg, who spent most of her childhood in this rambling building and is now an expert on his career, had arrived just as I did, and we convened at a big table her father had piled with boxes of files, like a lawyer preparing for a deposition.

“I guess I was always an archivist,” he said, smiling, surveying the spread, his glasses and ponderous forehead giving him an owllike bearing.

Continue reading the main story

Unlike some overexamined artists of his generation, Oldenburg enjoys interviews, and he had been through this routine dozens of times before. But today he seemed to be in the mood for some serious retrospection: The first drawings he pulled from a folder were ones he made in middle school and high school in Chicago, where his father, Gosta, a Swedish diplomat, had moved the family in 1936 from Oslo upon being posted to the United States as a consul.

His daughter looked over the profusion of drawings protected by plastic sleeves and said: “I always think I’ve seen everything that’s here. But I’ve never seen these before.”

Amy Adams Greats Cover

Growing up in wartime Chicago gave Oldenburg, a bookish child of Europe, a firm purchase on America’s brashness, inseparable from its boorishness and brutality. That sense informed the ragtag, anxious nature of his early pieces, work that seems to gain political relevance with each passing year. His childhood drawings — schematics of war planes, storyboard cartoons, caricatures of classmates — aren’t anything special. But they immediately reveal three things: He was a preternaturally talented draftsman from the start; he was always wickedly funny; and he has always had an engineer’s passion for the built world. It’s no accident that many of his best drawings over the years have taken the form of grandly elaborate blueprints and architectural renderings, making him a charter member of what I like to think of as the schematic school of late Modernism (other members would include Bruce Nauman, Lee Lozano and Chris Burden).

Art didn’t really grab Oldenburg until he was an adult. “The Art Institute of Chicago was a mystery to me back in those years,” he said. “Where I’d go was the Field Museum and look at things rather than looking at art. I think I’ve really always been more interested in things than in anything else.”

At Yale, which he entered in 1946, he was drawn to literature and studied with the formalist critic Cleanth Brooks, but he was an eccentric student at best. “I actually left once before I graduated,” he said. “One day, I just got on a train and came to New York and sat on a park bench in front of City Hall and read ‘Moby-Dick.’ ” His early 20s were spent in a peripatetic drift that was equally Kerouacian: cub reporter in Chicago, sent to find bodies floating in the river; ad agency stint drawing insects for an insecticide company; dishwasher in Oakland, where he traded drawings for rent. In San Francisco he met the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and in Los Angeles he feared for his life. “I sat next to two guys at a diner who were plotting a murder, honest to God. L.A. was really a terrifying place for me that first time.”

Photo

Oldenburg has lived on the far west side of SoHo since the early ’70s. Credit Pieter Hugo

But his wandering, he said, gave him the courage to try New York. He moved there in 1956, and it was as if the city had been waiting for him. The Abstract Expressionist revolution was running low on gas. The year before, Robert Rauschenberg had made “Bed,” one of his first so-called combines, a melding of painting and sculpture, by drawing and splashing paint on his pillow and his patchwork quilt and stretching them on a wooden frame. Not long before, Jasper Johns had begun his edge-to-edge American flags, rendering an icon not as an image in a painting but as an object in itself. Formal orthodoxies were being detonated in studios all over Manhattan, and Oldenburg could feel the tremors.

“I felt like the Ab Ex painters weren’t saying very much, and I wanted work that would say something, be messy, be a little mysterious,” he said. “Nineteen fifty-nine was the turning point. I was painting these brushy paintings — figurative — and then, thankfully, it all just fell apart.”

Drawing on a longstanding interest in the primitivism of Jean Dubuffet and thinkers about ritual and symbolism like Sigmund Freud and his pupil Wilhelm Stekel, he began making raw pieces that seemed to come straight from the id. They included the first iterations of Ray Gun, a mutable symbol for himself roughly in the shape of a toy laser pistol, a form that continues to fascinate him to this day. (On a visit to the studio’s second floor, he came across a piece of cardboard with three ray-gun shapes on it that appeared to be old raisin cookies nibbled into shape and then glued down. “Not sure what this was for,” he said, looking it over quizzically.) His other alter-ego, my favorite, is a geometrically minimalist mouse head that evokes Mickey and the reels of a film projector, as well as a kind of twilight-zone Modernist future. This symbol took its most improbable physical form in his “Mouse Museum.” An obsessive collection of small pieces and punning found objects (plastic bananas in conversation with dildos), the museum was born in his studio and eventually came to inhabit a snug, vitrine-filled, gallery-size structure shaped like the mouse head, designed by him and van Bruggen; the collection has been periodically exhibited, including a showing at Documenta 5 in Kassel, Germany, in 1972.

In the space of less than five years, in the short-lived but highly fertile gallery scene that sprung up in the East Village and at the legendary Green Gallery on 57th Street, he helped birth not only Pop Art but performance art as well, in maniacal productions with sculpture as props, staged with his first wife, Patty, now Patty Mucha, and compatriots who would later go on to fame as well, like Lucas Samaras and Carolee Schneemann. At one of these performances, “World’s Fair II” (1962), Oldenburg hung a soft sculpture depicting an upside-down New York City skyline from the ceiling in front of an audience in a rented storefront. Many performances consisted of the artist and Patty rolling around or dancing on a debris-covered floor. Writing at the time, the poet Frank O’Hara observed that Oldenburg “actually does what is most often claimed wrongly in catalog blurbs: transform his materials into something magical and strange.”

Continue reading the main story

AS HE APPROACHES his ninth decade, Oldenburg has slowed his once-furious pace of productivity, but he is still at work on public projects and large-scale sculpture. He’s finishing a private commission in California called “Dropped Bouquet,” a colorful maquette of which sits in his studio, and he’ll have a show of new works at Pace Gallery this month in N.Y.C. His energy — some of which goes into a stationary bike he is using to strengthen his legs — remains remarkable. Nearing the end of the third hour of our interview, he kept trying and failing to bring it to a close, spotting other things to talk about, ferrying me up and down in the building’s creaky old freight elevator, big enough to fit a small car.

“I like living in the studio,” he said. “You have the ability to see everything. And you can always change things any way you want them.”

Unlike some other old masters of the New York downtown scene (Jasper Johns, who now lives in Connecticut; Rauschenberg, who died in 2008 and spent much of the later part of his life in Florida) Oldenburg has remained resolutely in the city that nourished his work, with only a couple of periods away in Los Angeles and France, where he and van Bruggen bought and renovated a chateau.

“I don’t get out as much anymore, but I feel like the city is here when I want it,” he said. His daughter, who remembers the scavenged toys she and her brother were allowed to choose from the heaping garbage barrels her father amassed for his work, told me, “It’s always kind of a mystery to me how things still work their way in here. He’s very good at keeping things that he wants to use for later.”

As if to prove her point, he took us to see some small assemblage works he has been tinkering with, simple but unruly arrangements of inconsequential junk on small metal shelves. One in progress consisted of not much more than a cardboard figure of a pinup girl, a brown foam Berenstain Bears novelty headband, some paint-dipped stirrers and a piece of red rope. It looked unaccountably like a deconstructed view of Cezanne’s bathers.

“I put things here and I look at them for a long time and if they don’t belong, well, they’ll get up and walk.” He stared intently at a small plastic toy ladybug, perched tentatively on the edge of the conglomeration. “I told her to get lost,” he said, “but she’s still here.” Hopefully, he added, “Maybe she’ll stay.”

Continue reading the main story

Original Article:

Click here

0 notes