#Vernel Fournier

Text

Ahmad Jamal's Timeless Brilliance: Exploring the Legacy of "At the Pershing: But Not for Me"

Introduction:

In the annals of jazz history, certain albums stand out as defining moments that transcend their time of creation. “At the Pershing: But Not for Me,” released in 1958, is undoubtedly one such gem. Pianist Ahmad Jamal, accompanied by bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernell Fournier, crafted a masterpiece that not only marked a pivotal point in Jamal’s career but also left an…

View On WordPress

#Ahmad Jamal#At the Pershing: But Not for Me#Buddy Bernier#Classic Albums#Dizzy Gillespie#George Gershwin#Ira Gershwin#Israel Crosby#Jazz History#Miles Davis#Nat Simon#Vernel Fournier

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

One more from Ahmad Jamal, still back in the 50s, but now in '59. Love his right hand in this; it's limber, light (except when it isn't), and swinging like crazy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahmad Jamal “Emerald City Nights”

Ahmad Jamal “Emerald City Nights”

View On WordPress

#Aaron Diehl#Ahmad Jamal#Anthony Neweley#Chuck Lampkin#Frank Gant#Great American Songbook#Hiromi#Jamil Nasser#Jazz Detective#Jon Batiste#Kenny Barron#Leslie Bricusse#piano trio#Richard Evans#Vernel Fournier#Zev Feldman

0 notes

Photo

The dapper and sagacious Ahmad Jamal may have looked more like a UN delegate than a jazz musician, but he was recognised as a truly great jazz artist by some of the music’s most notable pioneers. Jamal, who has died aged 92, was hailed in the 1940s and 50s by Art Tatum and Miles Davis, and more recently by McCoy Tyner and Keith Jarrett. In the 90s, when a jazz piano-trio renaissance was being led by gifted newcomers such as Brad Mehldau, Jason Moran, Geri Allen and Esbjörn Svensson, Jamal did not retire to the sidelines but played better than ever. The former Wynton Marsalis pianist and composer Eric Reed has said that Jamal is to the piano trio “what Thomas Edison was to electricity”.

He was a fascinating philosopher of contemporary music and a lifelong critic of the entertainment business, which he accused of fleecing African-American artists. Although he recognised the structural and technical distinctions of jazz and European classical music, he was adamant that there was no superiority of one over the other in what he called “the emotional dimensions”. “You have to know what the hell you’re doing,” he told me in 1996, “whether you’re playing the body of work from Europe or the body of work from Louis Armstrong.”

Jamal was born Frederick Jones in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and regarded the eclectic musical culture of his birthplace as crucial to his development. His father was an open-hearth worker in the steel mills, but his uncle Lawrence played the piano and at only three years old Jamal was copying his playing by ear. He took lessons from seven, and would recall “studying Mozart along with Art Tatum”, unaware of white society’s widespread prejudice that European music was supposed to be superior to that of African-Americans. Significant influences in his early years were the music teacher Mary Cardwell Dawson (founder of the National Negro Opera Company), and his aunt Louise, who showered him with sheet music for the popular songs of the day. Pianists Tatum, Nat King Cole and Erroll Garner were among the young “Fritz” Jones’s principal jazz influences, and he also studied piano with James Miller at Westinghouse high school.

At 17 he toured with the former Westinghouse student George Hudson’s Count Basie-influenced orchestra, worked in a song-and-dance team, and wrote one of his most enduring themes, Ahmad’s Blues, at 18. Two years later he adopted Islam, and the name Ahmad Jamal. He also joined a group called the Four Strings, which became the Three Strings with the departure of its violinist, and caught the ear of the talent-spotting producer John Hammond, who signed the trio to Columbia’s Okeh label.

The public liked Jamal’s distinctive treatments of popular songs, and so did Davis. Developing his new quintet in 1955, Davis sent his rhythm section to study Jamal’s then drummer-less group. Davis liked Jamal’s pacing and use of space (the prevailing bebop jazz style was usually hyperactive), and he noticed that Jamal’s guitarist, Ray Crawford, often tapped the body of his instrument on the fourth beat. Davis told his drummer, Philly Joe Jones, to copy the effect with a fourth-beat rimshot, which became a characteristic sound of that ultra-hip Davis ensemble. Davis began to feature Jamal’s originals and arrangements in his own output, including New Rhumba (on his 1957 Miles Ahead collaboration with Gil Evans), and Billy Boy (on 1958’s classic Milestones session).

The gifted young Chicago bassist Israel Crosby joined the trio in 1955, and the following year the percussionist Vernel Fournier – who fulfilled Jamal’s requirements for a subtle hand-drummer as well as orthodox sticks-player – replaced Crawford. The group became the house band at the Pershing Hotel in Chicago, and one night in January 1958 they recorded more than 40 tracks there. One was Poinciana, which had been a hit tune from the 1952 movie Dreamboat. Jamal modernised its Latin groove, maintained a catchy hook throughout the improvisation, and found himself with a pop hit that stayed in the charts for two years.

Eight songs from that night, including Poinciana, made up the million-selling album At the Pershing: But Not for Me. Jamal’s newfound wealth led him to branch out into club ownership by opening the Alhambra in Chicago, though the venture barely lasted a year. Crosby and Fournier left for the pianist George Shearing’s group in 1962, and Jamal recorded the Latin-influenced Macanudo album the next year, with a new trio and a full orchestra. He also explored his cultural and ancestral roots in Africa, then recorded Heat Wave in 1966 – with a new group (Jamil Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums) and a more contemporary feel, reflected in the funkier approach to his old piano hero Garner’s Misty.

Jamal’s knack of keeping audiences mesmerised with unexpected modulations, time changes and catchy riffs, while never losing the undercurrent of the tune, was still unmistakably intact. His trademark device of insinuating a song – through toying with its bassline or its characteristic groove, but endlessly delaying the appearance of the tune – was adopted by many later jazz pianists, including such contemporary masters as Mehldau.

In 1970 Jamal recorded Johnny Mandel’s M*A*S*H theme for the movie’s soundtrack, and with the albums Jamaica (in 1974, which included Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man as well as M*A*S*H) and Intervals (1979, which included a Steely Dan cover), showed he was not averse to toying with pop forms and even electric pianos. But he soon returned to the jazz of his roots. In 1982 he made the live album American Classical Music (it was the term he always preferred to the word “jazz”), sustained a steady output through the decade, and with Chicago Revisited (1992) sounded as assured and inventive as ever.

Now in his 60s, Jamal began to develop a higher profile in Europe. Sessions for the Dreyfus label in France led to The Essence (issued in three parts in the 90s), and found him in full flight with the saxophonists George Coleman and Stanley Turrentine and the trumpeter Donald Byrd. In 1995 his version of Music, Music, Music and the original take of Poinciana were featured in the Clint Eastwood film The Bridges of Madison County. He made what he regarded as one of his best recordings with Live in Paris 1996 (featuring Coleman again), and returned to the city to celebrate his 70th birthday in 2000 with Coleman; he was in inspired form on what would be released as the album A l’Olympia (2001).

With the exciting James Cammack on bass and Idris Muhammad on drums, Jamal’s composing blossomed. Striking originals dominated his 2003 album In Search of Momentum, and he even made a faintly stagey but soulful foray into singing, amid a raft of virtuoso keyboard displays, on After Fajr (2005).

Jamal’s alertness to an irresistible riff, like his keyboard contemporary Herbie Hancock’s, made him a favourite with hip-hop artists, and De La Soul’s Stakes Is High and Nas’s The World Is Yours were among many unmistakable testaments to that. Mosaic Records’ nine-CD set of his game-changing work in the late 1950s and early 60s was released in 2011, his group made a spectacular live appearance in London in 2014, and his last album releases came in 2022 with Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse, parts one and two, featuring live recordings made in Seattle during the 60s. A third in the series is due for release this year.

Jamal was married and divorced three times – to Virginia Wilkins, Sharifah Frazier and Laura Hess-Hay. He is survived by a daughter, Sumayah, from his second marriage, and two grandchildren.

🔔 Ahmad Jamal (Frederick Russell Jones), musician, born 2 July 1930; died 16 April 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AllMusic Staff Pick:

Ahmad Jamal Trio

At the Pershing: But Not for Me

A cool performance in every sense of the word, this live recording captures the nascent trio in sharp form, cooking through eight songs in just over a half-hour. Pianist Ahmad Jamal, bassist Israel Crosby, and drummer Vernell Fournier feed off each other in this blazing set highlighted by the classic rendition of "Poinciana."

- Zac Johnson

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

FROM THE SMALL’S ARCHIVE: AARON GOLDBERG with Mats Sandahl and Eviatar Slivnik, MEZZROW’S, 13 OCTOBER 2023, 9 pm set

Sometimes it’s the rhythm section, sometimes it’s the pianist. This time it was AARON GOLDBERG who has done some fine with with Omer Avital and Branford Marsalis but who hasn’t quite moved into the can’t miss category. I fostered that suspicion as they opened with the rather programmatic Dreaming of Freedom written by a French Caribbean tenor saxist who visited one of the colonial prisons. It was nice but felt composed and atmospheric more than jazz. A contrafact of Joe Henderson’s Serenity was unsettled but not harsh, but didn’t quite resolve despite obvious talent by all three.

Sometimes it should be the rhythm section. Both were unknown to me—no longer. Mats Sandahl found clever spaces for comments, both harmonic and rhythmic. But Eviatar Slivnik was even more striking. Goldberg aptly dubbed him “Tasty.” He had the Mezzrow’s/trio dynamics just right while adding ear cathching touches at every turn. He had a cowbell on his tom during Black Orpheus, in the middle of a Brazilian medley, that moved that already sinuous beat around magically.

That medley turned the set around for me. Goldberg let some jazz break out and they simmered things nicely. Then it got exciting. They took off on McCoy Tyner’s Effendi which swung richly, but with subtle, not obvious, power. The follow up was Poinciana with a clever rhythmic hiccup, but still properly pretty and swinging. Sandahl and Slivnik evoked Israel Crosby and Vernel Fournier from Ahmad Jamal’s trio while properly doing their own thing. Hearing Goldberg paying tribute to Tyner and Jamal in quick succession and sounding like Aaron Goldberg throughout was a jazz moment that I didn’t see coming.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Video

youtube

Ahmad Jamal - “Autumn Leaves”

Piano - Ahmad Jamal

Bass – Israel Crosby

Drums – Vernell Fournier

#ahmad jamal#piano trio#jazz#jazz music#autumn leaves#israel crosby#vernell fournier#ahmad's blues#piano#piano jazz

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ahmad Jamal Recalls At the Pershing and More

Charles Waring drew some wonderful information from Ahmad Jamal about his early years and the unprecedented success of his 1956 album At The Pershing, with its iconic treatment of Poinciana. It fascinating to hear Jamal’s recollections of those formative, life-changing years.

-Michael Cuscuna

Read and listen from UDiscover…

Follow: Mosaic Records Facebook Tumblr Twitter

#Ahmad Jamal#piano#At the Pershing#Poinciana#classic jazz#Miles Davis#Isrel Crosby#Vernell Fournier#Michael Cuscuna

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

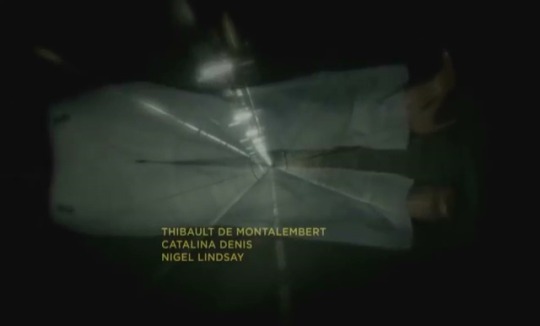

The Tunnel - Sky Atlantic - October 16, 2013 - December 14, 2017 / Canal+ - November 11, 2013 - June 18, 2018

Crime Drama (24 episodes)

Running Time: 60 minutes

Stars:

Stephen Dillane as Det. Chief Inspector Karl Roebuck

Clémence Poésy as Captain (later Commandant) Elise Wassermann

Angel Coulby as Laura Roebuck (Series 1–2)

Thibault de Montalembert as Commander Olivier Pujol

Cédric Vieira as Lieutenant Phillipe Viot

Thibaut Evrard as Gaël (Series 1–2)

Fanny Leurent as Officer Julie (Series 1–2)

William Ash as Det. Constable Boleslaw 'BB' Borowski (Series 2–3)

Juliette Navis as Lieutenant Louise Renard (Series 2–3)

Laura de Boer [nl] as Eryka Klein (Series 2)

Marie Dompnier as Madeleine Fournier (Series 2)

Emilia Fox as Vanessa Hamilton (Series 2)

Johan Heldenbergh as Robert Fournier (Series 2)

Hannah John-Kamen as Rosa Persaud (Series 2)

Stanley Townsend as Chief Superintendent Mike Bowden (Series 2)

Christine Bottomley as Helena Carver (Series 3)

William Gaminara as Wesley Pollinger (Series 3)

Valentin Merlet [fr] as Commander Astor Chaput (Series 3)

Felicity Montagu as Chief Superintendent Winnie Miles (Series 3)

Angeliki Papoulia as Lana Khasanović (Series 3)

Sharon Rooney as Kiki Stokes (Series 3)

Brian Vernel as Anton Stokes (Series 3)

#The Tunnel#TV show#Sky Atlantic#Canal+#Crime Drama#2000's#Stephen Dillane#Clemence Poesy#Angel Coulby

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahmad Jamal: A Jazz Icon Redefining Musical Boundaries

Introduction:

Certain people leave an enduring impression on the jazz world, forever changing its environment and influencing future generations of artists. Ahmad Jamal is one such legend; he was a pianist, composer, and bandleader who not only expanded the parameters of jazz but also mesmerized audiences with his innovative methods and singular musical vision. Jamal had a career spanning more…

View On WordPress

#Ahmad Jamal#Art Tatum#Herbie Hancock#Israel Crosby#Jazz History#Jazz Pianists#Keith Jarrett#Live at the Pershing: But Not for Me#Miles Davis#Nat King Cole#Vernel Fournier

0 notes

Text

youtube

Ahmad Jamal was a genius. I think there is now a general consensus about this, although it took a while for take hold. That Miles loved him probably helped, although the minimalism he's famous for also came across as being a little out of step with what was happening in 50s jazz. "Poinciana" is a famously long song to have been a hit; amusingly, it's basically twice as long as anything else on "At The Pershing." It doesn't feel long, though, instead feeling kind of economical (along with feeling groovy and feeling good).

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Recorded Live at The Blackhawk, San Francisco, July 5 & 6, 1963

George Shearing - Piano

Ron Anthony - Guitar

Gary Burton - Vibraphone

Gene Chericohe - Bass

Vernel Fournier - Drums

Armando Peraza - Congas

13 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Poinciana – Ahmad Jamal

American jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal was born Frederick Jones in July 1930, (the same year as Sean Connery), and has been playing, composing, leading and teaching jazz for over five decades. Jamal’s first album The Piano Scene of Ahmad Jamal was released in 1955 with recordings from as early as ‘51, and his most recent album Ballades was released just last year in 2019.

Rather than chase the virtuosic speed and dexterity of bebop, Jamal emphasised space and time in his music, pursuing what would later become known as cool jazz.

Jamal is credited with having a great influence on Miles Davis, who has stated that he was impressed by Jamal's rhythmic sense and his "concept of space, his lightness of touch, his understatement".

Today’s track Poinciana was written by Nat Simon in 1936. It’s the title track of an Ahmad Jamal album by the same name, released in 1963, featuring Ahmad Jamal on piano, Ray Crawford on guitar, Israel Crosby on bass, and Vernel Fournier on drums.

Poinciana became somewhat of a theme song of Ahmad Jamal. Tucked into the middle of his latest album Ballades is a solo rendition of it which is described by Downbeat Magazine’s reviewer Gary Fukushima as stripped down, dark with nostalgia, poignant and powerful. Downbeat gave the album four and a half stars.

Ahmad Jamal turned 90 this year. Prior to the pandemic he was still performing live in concert.

– Bozzie 🎷

0 notes

Text

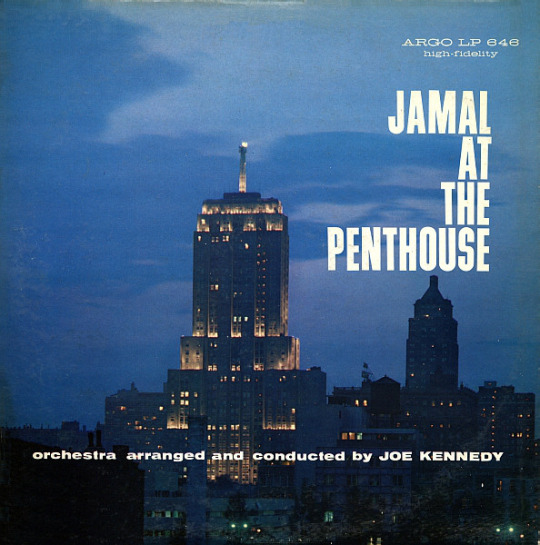

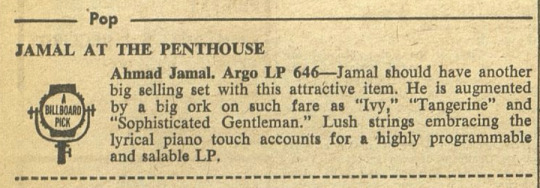

February 27, 1959

Ahmad Jamal’s trio — Jamal, Israel Crosby and Vernell Fournier — are featured on this sort of goofy-sounding set with an orchestra that was recorded in part on February 27, 1959 at Nola Penthouse Studio (inside the Steinway Building on 57th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues). It’s a good example of what jazz-pop crossover sounded like at that time — in Billboard, Jamal At The Penthouse was reviewed as a pop record.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON AHMAD JAMAL AND MILES DAVIS WITH RED GARLAND

When Ahmad Jamal died last month, I took an extended but intermittent listen to the glorious 9 hours 28 minutes of his 1956-1962 trio recordings on Argo which includes his But Not for Me: At the Pershing but also at his Alhambra and at the Blackhawk.

I have recounted often how Oscar Peterson with Ray Brown and Ed Thigpen were my exposure to the jazz trio when I was 8. It was formative—an immaculate stylist, hard swinging rhythm section, a deep repertoire from the Great American Song Book. That’s what jazz sounds like to me.

In a different, perhaps more logical universe, Ahmad Jamal/Israel Crosby/Vernell Fournier would have been an equally addictive gateway drug. That universe would be more logical because I worked back quickly from Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew to Kind of Blue, sure and of course, but also the very first albums on Columbia with Coltrane and then Workin’/Steamin’/Cookin’/Relaxin’ from those sessions that wrapped up the Prestige contract.

Muted trumpet for dry solos on standards, a crisp but spacious rhythm section. That too is what jazz sounds like to me. Miles rather famously championed Jamal for “his concept of space, his lightness of touch, his understatement” in the face of dismissive critics who thought Jamal little more than a cocktail pianist. Listening to the first great Miles quintet as the palate cleanser between extended stints with the Jamal on Argo compendium, I hear the impact—on Miles as much as anyone but also on Red Garland.

So the Jamal trio could have just as likely won me to the idiom even though Peterson is quite a different pianist—full, muscular, driving—than Jamal who, yes, is understated, light with deceptive figures in the highest octaves against sparer chords. But both know the GASB and many of its deepest cuts, relying on that more than their compositions. That said, Peterson’s Canadiana Suite is perhaps his only memorable album qua album. Otherwise, the Peterson in my collection was/is anthologies from sessions with strong rhythm sections which I selected on the basis of the particular tunes available. Some very early recordings for Norman Granz were already distinctive and I can’t say that I can place Peterson’s recordings by era. The flourishes, the evocations of Art Tatum, the hard swinging were there from the start.

The Jamal Argo recordings are pretty remarkable and distinctive. Israel Crosby isn’t Ray Brown because nobody is, but he’s a vigorous collaborator and, given Jamal’s space, he can push things around without having to swagger as Brown could with Peterson. Vernell Fournier is oh so tasty. But don’t discount Jamal’s drive and the rhythmic punch he leads.

And then there’s the impact on Miles which gives these Argo recordings a resonance and freshness. I don’t want to live in a world without Oscar Peterson’s music, but he doesn’t matter in quite the way that Jamal does.

It’s not only Garland who incorporates the Jamal ethos, it’s Miles himself and Paul Chambers taking advantage of space in the same way that Crosby did. I have to imagine Philly Joe Jones was perfectly adaptable to any circumstance. Coltrane too absorbed this experience and Monk too before modes, sheets of sound, running chords, and his ultimate lift off.

But, back in the day, I only had an Impulse anthology of Jamal’s work later in the 1960s and early 1970s. Fine stuff but I didn’t listen to his work over the past 50 years. I might go looking for some of it.

But, it’s hard. Jamal on Argo is part of what jazz sounds like to me.

0 notes