#Turkey Turcomans

Photo

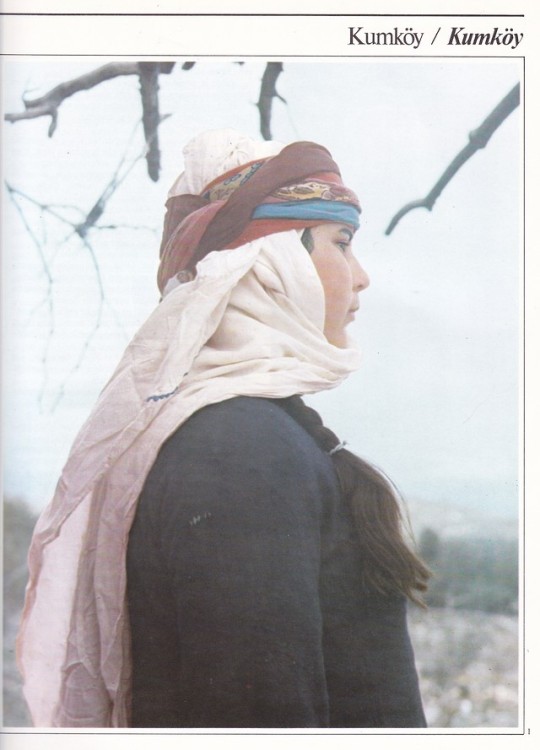

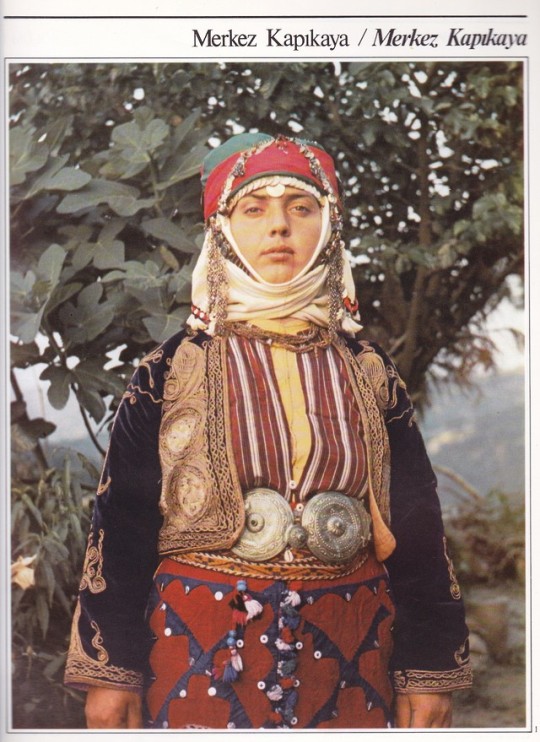

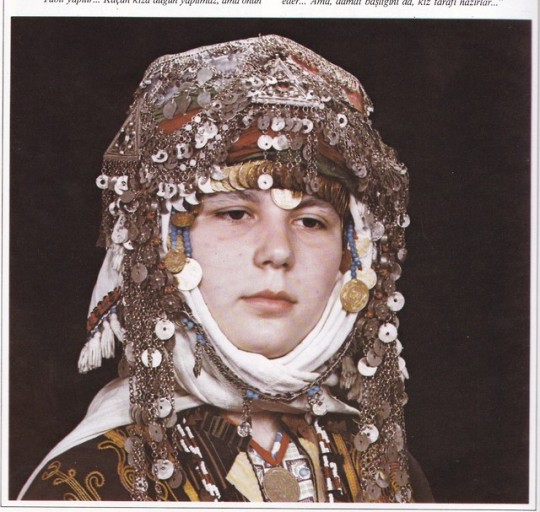

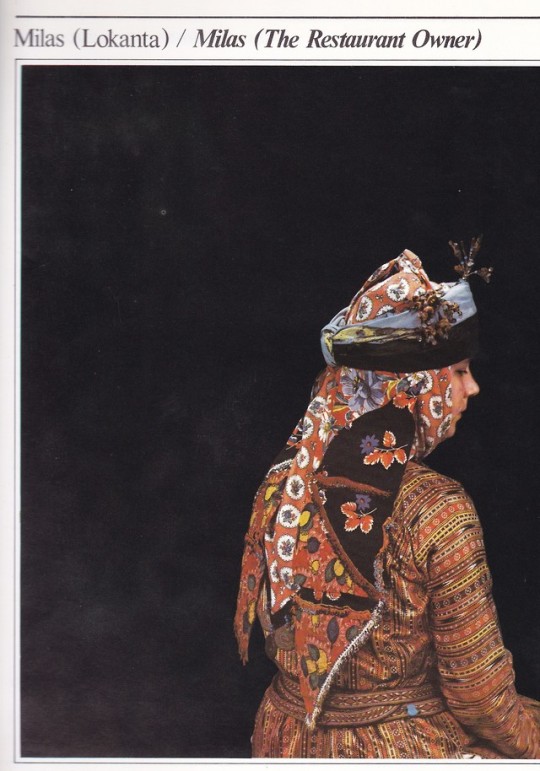

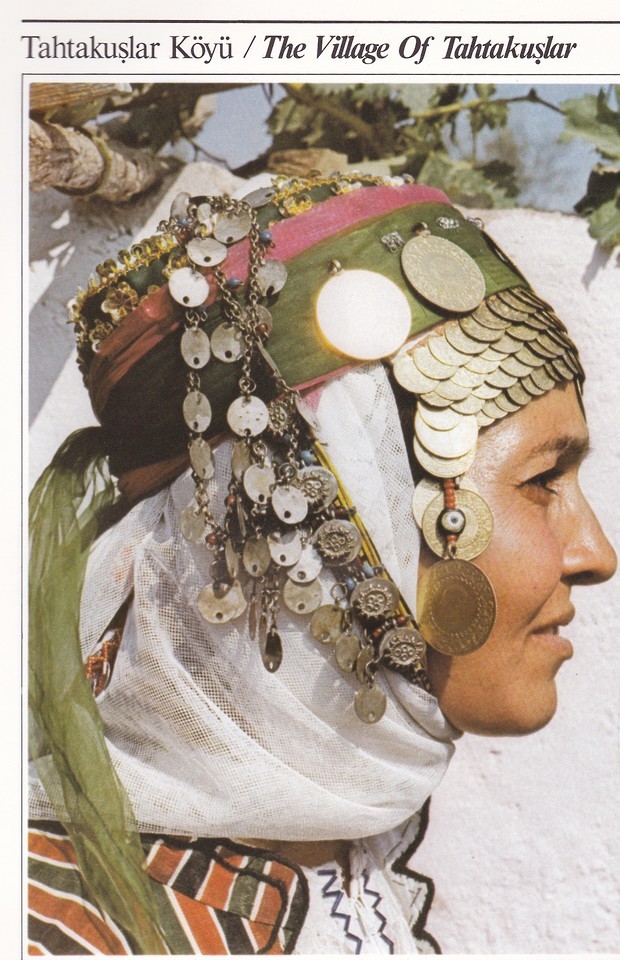

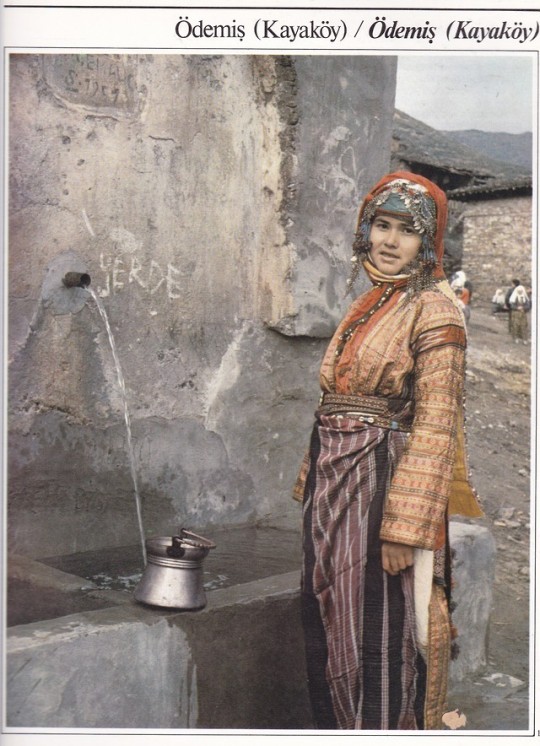

Turkey Turcoman girls in traditional clothes

Geleneksel kıyafetleri içinde Türkiye Türkmen'i kızları

#turkish#turkey#Turcomans#Turkey Turcomans#türkiye türkmeni#geleneksel Türk giyimi#türk giyimi#turkic#oguz turkleri#oghuz turks#Oğuz Türkleri#Türkiye#türkiye türkmenleri#Turkish people

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

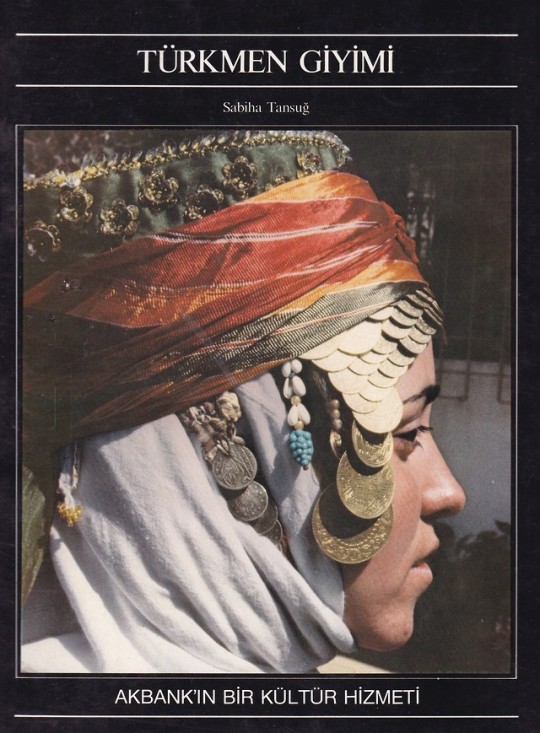

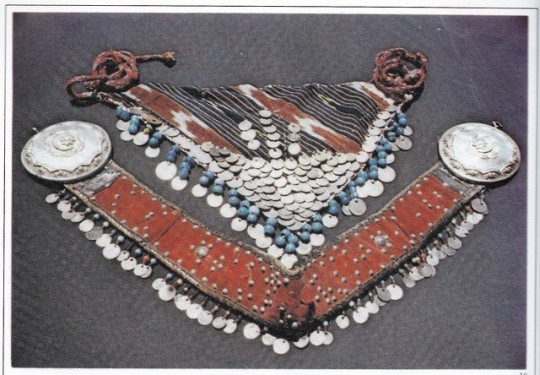

Türkmen Giyimi

Turkmen Costumes

Sabiha Tansuğ

Akbank Kültür Yayınları , Istanbul 1985, 64 pages, Turkish and English

euro 35,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

A study on traditional clothing of Turkoman in the Aegean Region of Turkey. with many illustrations. Also important for traditional Turcoman folkloric handicraft and history of art

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter:@fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

#Turkmen Costumes#folk costumes#Turchia#Aegean Sea region#Turkoman#traditional clothing#fashion inspiration#traditional jewelry#fashionbooksmilano

176 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople and its Constantino neighborhood must have been, on the whole, very pie a city of pleasant. There were villas on the neighboring shores of the Bosphorus, on the Marmora towards San Stefano, and on the shore beyond Chalcedon, where one might escape from the great heat of summer and spend half the year in a country life, while the well-built palaces of the city were warm and comfortable in winter. The inhabitants appreciated these privileges and were proud of the Queen of Cities. The Byzantine noble, when compelled to leave it, longed to be back again. He loved the sacred city and the Marmora, where the zephyrs blew so softly, where the fountains were so pleasant, the baths so delicious, where the dolphins and other varieties of fish disported themselves on the surface of the waters, and where the nightingales and other singing birds made delightful music for those who flocked from all parts of the world to hear it. Constantinople was a city of business, but it was likewise a city of pleasure.

Every-thing that wealth could buy could be secured within its walls. As in our own days men who have acquired money in remote regions flock to Paris or London to take part in the luxurious life of these capitals, so the Cyprian, the islander, the trader from many a remote province or country, went to Constantinople as the place where he could make the best investment of his money in pleasure. But the inhabitant of what the Western writers then called Romania had a greater inducement to go to Constantinople than the inhabitant of Manchester or Marseilles to go to London and Paris. Property is, in modern times, as safe in these provincial cities as in the capitals of the countries in which they are situated, but property at Smyrna or elsewhere in Asia Minor was liable to attacks from the Turks; property in Mitylene or others of the islands of the Aegean and along the seaboard of the empire had to be continually protected from the pirates who were already infesting the neighboring seas.

As so secure as Constantinople

No city was regarded as so secure as Constantinople, and amid this security the wealthy man could find rarer silks, finer linen, and purer dyed purple, richer furs, dishes of greater delicacy, and wines of more rare and costly vintage than in the provinces. Precious stones and jewelry of every kind, including those ropes of pearls which are yet to be seen in daily wear at Damascus and other remote cities of Turkey, and to the display of which the inhabitants of Eastern Europe, like those of Asia, have always attached great importance, might be more safely worn, could be shown to more people Visit Bulgaria, and would be more highly appreciated than in the provincial towns.

The Crusaders regarded the luxurious dresses of the Bjrzantines as marks of effeminacy, just as a Turcoman horde clothed in sheepskin, marching upon Paris, would bo sure to regard the luxury of the capital as a sign that the manliness had departed from the nation. The Byzantines looked on the rough and ill-dressed Crusaders as rude and uncouth barbarians, unskilled in science, ignorant of art and literature, and entire strangers to the luxuries of civilization. The Crusaders are never weary of calling attention to the luxury and the wealth of the inhabitants of Constantinople, and Nicetas himself, the chief Byzantine historian of this period, tells several stories against his own countrymen of the fault found by the Crusaders with the effeminate character of this luxury. We may be sure, however, that the Byzantine point of view was far different. All the pleasures of nature and of art were his.

The climate was safe from the great heat

The climate was safe from the great heat of Smyrna or the cold of even a few miles farther north on the Black, that is, the rough, bleak, Sea. The Golden Horn, the Marmora, and the Bosphorus were bright during six or seven months of the year with gayly decked and graceful caiques, probably not much unlike their present representatives, except that they were higher in the stem and stern, and thus more graceful in form. Carefully trained oarsmen from the Greek islands or from the neighboring shores were to be had at a cheap rate, and each noble family had its own crews with gay distinctive badges. The ruins

now existing in the neighborhood of Constantinople show how largely the nobles led a villa life on the borders of the sea.

No city in the world is so largely gifted by nature with the requirements for a happy life. The bright sky, the blue, tideless waters of the Marmora, the vine-producing shores, the forests which even yet have not been so far destroyed as to drive away the nightingale, the flights of quail which pass the city twice every year and still fall occasionally in the streets of Constantinople, the never-failing supply of fish and other food, the presence of birds of beautiful plumage and song, all contributed to the joyous life of this city of pleasure.

0 notes

Photo

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople and its Constantino neighborhood must have been, on the whole, very pie a city of pleasant. There were villas on the neighboring shores of the Bosphorus, on the Marmora towards San Stefano, and on the shore beyond Chalcedon, where one might escape from the great heat of summer and spend half the year in a country life, while the well-built palaces of the city were warm and comfortable in winter. The inhabitants appreciated these privileges and were proud of the Queen of Cities. The Byzantine noble, when compelled to leave it, longed to be back again. He loved the sacred city and the Marmora, where the zephyrs blew so softly, where the fountains were so pleasant, the baths so delicious, where the dolphins and other varieties of fish disported themselves on the surface of the waters, and where the nightingales and other singing birds made delightful music for those who flocked from all parts of the world to hear it. Constantinople was a city of business, but it was likewise a city of pleasure.

Every-thing that wealth could buy could be secured within its walls. As in our own days men who have acquired money in remote regions flock to Paris or London to take part in the luxurious life of these capitals, so the Cyprian, the islander, the trader from many a remote province or country, went to Constantinople as the place where he could make the best investment of his money in pleasure. But the inhabitant of what the Western writers then called Romania had a greater inducement to go to Constantinople than the inhabitant of Manchester or Marseilles to go to London and Paris. Property is, in modern times, as safe in these provincial cities as in the capitals of the countries in which they are situated, but property at Smyrna or elsewhere in Asia Minor was liable to attacks from the Turks; property in Mitylene or others of the islands of the Aegean and along the seaboard of the empire had to be continually protected from the pirates who were already infesting the neighboring seas.

As so secure as Constantinople

No city was regarded as so secure as Constantinople, and amid this security the wealthy man could find rarer silks, finer linen, and purer dyed purple, richer furs, dishes of greater delicacy, and wines of more rare and costly vintage than in the provinces. Precious stones and jewelry of every kind, including those ropes of pearls which are yet to be seen in daily wear at Damascus and other remote cities of Turkey, and to the display of which the inhabitants of Eastern Europe, like those of Asia, have always attached great importance, might be more safely worn, could be shown to more people Visit Bulgaria, and would be more highly appreciated than in the provincial towns.

The Crusaders regarded the luxurious dresses of the Bjrzantines as marks of effeminacy, just as a Turcoman horde clothed in sheepskin, marching upon Paris, would bo sure to regard the luxury of the capital as a sign that the manliness had departed from the nation. The Byzantines looked on the rough and ill-dressed Crusaders as rude and uncouth barbarians, unskilled in science, ignorant of art and literature, and entire strangers to the luxuries of civilization. The Crusaders are never weary of calling attention to the luxury and the wealth of the inhabitants of Constantinople, and Nicetas himself, the chief Byzantine historian of this period, tells several stories against his own countrymen of the fault found by the Crusaders with the effeminate character of this luxury. We may be sure, however, that the Byzantine point of view was far different. All the pleasures of nature and of art were his.

The climate was safe from the great heat

The climate was safe from the great heat of Smyrna or the cold of even a few miles farther north on the Black, that is, the rough, bleak, Sea. The Golden Horn, the Marmora, and the Bosphorus were bright during six or seven months of the year with gayly decked and graceful caiques, probably not much unlike their present representatives, except that they were higher in the stem and stern, and thus more graceful in form. Carefully trained oarsmen from the Greek islands or from the neighboring shores were to be had at a cheap rate, and each noble family had its own crews with gay distinctive badges. The ruins

now existing in the neighborhood of Constantinople show how largely the nobles led a villa life on the borders of the sea.

No city in the world is so largely gifted by nature with the requirements for a happy life. The bright sky, the blue, tideless waters of the Marmora, the vine-producing shores, the forests which even yet have not been so far destroyed as to drive away the nightingale, the flights of quail which pass the city twice every year and still fall occasionally in the streets of Constantinople, the never-failing supply of fish and other food, the presence of birds of beautiful plumage and song, all contributed to the joyous life of this city of pleasure.

0 notes

Photo

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople and its Constantino neighborhood must have been, on the whole, very pie a city of pleasant. There were villas on the neighboring shores of the Bosphorus, on the Marmora towards San Stefano, and on the shore beyond Chalcedon, where one might escape from the great heat of summer and spend half the year in a country life, while the well-built palaces of the city were warm and comfortable in winter. The inhabitants appreciated these privileges and were proud of the Queen of Cities. The Byzantine noble, when compelled to leave it, longed to be back again. He loved the sacred city and the Marmora, where the zephyrs blew so softly, where the fountains were so pleasant, the baths so delicious, where the dolphins and other varieties of fish disported themselves on the surface of the waters, and where the nightingales and other singing birds made delightful music for those who flocked from all parts of the world to hear it. Constantinople was a city of business, but it was likewise a city of pleasure.

Every-thing that wealth could buy could be secured within its walls. As in our own days men who have acquired money in remote regions flock to Paris or London to take part in the luxurious life of these capitals, so the Cyprian, the islander, the trader from many a remote province or country, went to Constantinople as the place where he could make the best investment of his money in pleasure. But the inhabitant of what the Western writers then called Romania had a greater inducement to go to Constantinople than the inhabitant of Manchester or Marseilles to go to London and Paris. Property is, in modern times, as safe in these provincial cities as in the capitals of the countries in which they are situated, but property at Smyrna or elsewhere in Asia Minor was liable to attacks from the Turks; property in Mitylene or others of the islands of the Aegean and along the seaboard of the empire had to be continually protected from the pirates who were already infesting the neighboring seas.

As so secure as Constantinople

No city was regarded as so secure as Constantinople, and amid this security the wealthy man could find rarer silks, finer linen, and purer dyed purple, richer furs, dishes of greater delicacy, and wines of more rare and costly vintage than in the provinces. Precious stones and jewelry of every kind, including those ropes of pearls which are yet to be seen in daily wear at Damascus and other remote cities of Turkey, and to the display of which the inhabitants of Eastern Europe, like those of Asia, have always attached great importance, might be more safely worn, could be shown to more people Visit Bulgaria, and would be more highly appreciated than in the provincial towns.

The Crusaders regarded the luxurious dresses of the Bjrzantines as marks of effeminacy, just as a Turcoman horde clothed in sheepskin, marching upon Paris, would bo sure to regard the luxury of the capital as a sign that the manliness had departed from the nation. The Byzantines looked on the rough and ill-dressed Crusaders as rude and uncouth barbarians, unskilled in science, ignorant of art and literature, and entire strangers to the luxuries of civilization. The Crusaders are never weary of calling attention to the luxury and the wealth of the inhabitants of Constantinople, and Nicetas himself, the chief Byzantine historian of this period, tells several stories against his own countrymen of the fault found by the Crusaders with the effeminate character of this luxury. We may be sure, however, that the Byzantine point of view was far different. All the pleasures of nature and of art were his.

The climate was safe from the great heat

The climate was safe from the great heat of Smyrna or the cold of even a few miles farther north on the Black, that is, the rough, bleak, Sea. The Golden Horn, the Marmora, and the Bosphorus were bright during six or seven months of the year with gayly decked and graceful caiques, probably not much unlike their present representatives, except that they were higher in the stem and stern, and thus more graceful in form. Carefully trained oarsmen from the Greek islands or from the neighboring shores were to be had at a cheap rate, and each noble family had its own crews with gay distinctive badges. The ruins

now existing in the neighborhood of Constantinople show how largely the nobles led a villa life on the borders of the sea.

No city in the world is so largely gifted by nature with the requirements for a happy life. The bright sky, the blue, tideless waters of the Marmora, the vine-producing shores, the forests which even yet have not been so far destroyed as to drive away the nightingale, the flights of quail which pass the city twice every year and still fall occasionally in the streets of Constantinople, the never-failing supply of fish and other food, the presence of birds of beautiful plumage and song, all contributed to the joyous life of this city of pleasure.

0 notes

Photo

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople

Life among the wealthier classes of Constantinople and its Constantino neighborhood must have been, on the whole, very pie a city of pleasant. There were villas on the neighboring shores of the Bosphorus, on the Marmora towards San Stefano, and on the shore beyond Chalcedon, where one might escape from the great heat of summer and spend half the year in a country life, while the well-built palaces of the city were warm and comfortable in winter. The inhabitants appreciated these privileges and were proud of the Queen of Cities. The Byzantine noble, when compelled to leave it, longed to be back again. He loved the sacred city and the Marmora, where the zephyrs blew so softly, where the fountains were so pleasant, the baths so delicious, where the dolphins and other varieties of fish disported themselves on the surface of the waters, and where the nightingales and other singing birds made delightful music for those who flocked from all parts of the world to hear it. Constantinople was a city of business, but it was likewise a city of pleasure.

Every-thing that wealth could buy could be secured within its walls. As in our own days men who have acquired money in remote regions flock to Paris or London to take part in the luxurious life of these capitals, so the Cyprian, the islander, the trader from many a remote province or country, went to Constantinople as the place where he could make the best investment of his money in pleasure. But the inhabitant of what the Western writers then called Romania had a greater inducement to go to Constantinople than the inhabitant of Manchester or Marseilles to go to London and Paris. Property is, in modern times, as safe in these provincial cities as in the capitals of the countries in which they are situated, but property at Smyrna or elsewhere in Asia Minor was liable to attacks from the Turks; property in Mitylene or others of the islands of the Aegean and along the seaboard of the empire had to be continually protected from the pirates who were already infesting the neighboring seas.

As so secure as Constantinople

No city was regarded as so secure as Constantinople, and amid this security the wealthy man could find rarer silks, finer linen, and purer dyed purple, richer furs, dishes of greater delicacy, and wines of more rare and costly vintage than in the provinces. Precious stones and jewelry of every kind, including those ropes of pearls which are yet to be seen in daily wear at Damascus and other remote cities of Turkey, and to the display of which the inhabitants of Eastern Europe, like those of Asia, have always attached great importance, might be more safely worn, could be shown to more people Visit Bulgaria, and would be more highly appreciated than in the provincial towns.

The Crusaders regarded the luxurious dresses of the Bjrzantines as marks of effeminacy, just as a Turcoman horde clothed in sheepskin, marching upon Paris, would bo sure to regard the luxury of the capital as a sign that the manliness had departed from the nation. The Byzantines looked on the rough and ill-dressed Crusaders as rude and uncouth barbarians, unskilled in science, ignorant of art and literature, and entire strangers to the luxuries of civilization. The Crusaders are never weary of calling attention to the luxury and the wealth of the inhabitants of Constantinople, and Nicetas himself, the chief Byzantine historian of this period, tells several stories against his own countrymen of the fault found by the Crusaders with the effeminate character of this luxury. We may be sure, however, that the Byzantine point of view was far different. All the pleasures of nature and of art were his.

The climate was safe from the great heat

The climate was safe from the great heat of Smyrna or the cold of even a few miles farther north on the Black, that is, the rough, bleak, Sea. The Golden Horn, the Marmora, and the Bosphorus were bright during six or seven months of the year with gayly decked and graceful caiques, probably not much unlike their present representatives, except that they were higher in the stem and stern, and thus more graceful in form. Carefully trained oarsmen from the Greek islands or from the neighboring shores were to be had at a cheap rate, and each noble family had its own crews with gay distinctive badges. The ruins

now existing in the neighborhood of Constantinople show how largely the nobles led a villa life on the borders of the sea.

No city in the world is so largely gifted by nature with the requirements for a happy life. The bright sky, the blue, tideless waters of the Marmora, the vine-producing shores, the forests which even yet have not been so far destroyed as to drive away the nightingale, the flights of quail which pass the city twice every year and still fall occasionally in the streets of Constantinople, the never-failing supply of fish and other food, the presence of birds of beautiful plumage and song, all contributed to the joyous life of this city of pleasure.

0 notes

Text

Nomads (Yoruks)

Throughout the coastal region of Turkey You will come across groups of nomadic herders, the yörüks, who in the winter come down to the pastures by the coast and in the summer, when the sun shrivels the vegetation on the coast, travel up into themountains to the yaylas, the high mountain plateaus and valleys where there is sufficient grass and fodder for the animals until the autumn rains again regenerate the pastures on the coast. In Lycia you will see a few of the traditional black goat-hair tents, usually covered in plastic sheets nowadays, of the truly nomadic yörüks, though many now have more permanent houses on the coast and in the mountains. In other parts of Turkey there are larger numbers of these nomads, who carry everything with them on donkeys and camels along with their flocks of sheep and goats. To control the large flocks of sheep and guard their property, a large breed ofdog is employed and these animals can be ferocious beasts, keep well clear of them. They are usually bred in the East to take on the wolves that used to, and sometimes still do, attack the flocks, and these large dogs could successfully and will take on a wolf.

Though the life of the yörüks is becoming less nomadic in modern Turkey and they are losing many of their traditions, they still make superb kilimswith patterns and colors particular to the clan and region they belong to. The dress of these nomadic herdsmen has changed and though you still see some in the black shaggy goats-hair capes, more and more have adopted western style dress. The women more traditionally wear the 'salvar', the baggy trousers and short jacket, usually in a floral material, and on their heads a scarf cleverly arranged and knotted so it looks almost like a hat.

The Yörüks are not gypsies as is sometimes suggested. Their origins are probably from the indigenous peoples of Anatolia and it is likely they were here before the Turcoman tribes migrated down from the North. They do not wander the length and breadth of Turkey, but have definite routes and areas in the lowlands and highlands bordering the coast. They are a proud people who have to some extent been left behind in rapidly modernizing Turkey and their traditional routes and rights would appear to have been overlooked as roads are cut through the country and property is snapped up by developers.

0 notes

Text

"Bridal costume from Muğla. Urban, 1925-1950. With goldwork embroidered silk ‘üçetek’ (robe with three panels) and önlük/peşkir (apron; ‘two-sided’ silk embroidery on linen). The round mirror on the hat is an amulet against the ‘evil eye’. Except for that monumental hat, this costume was also worn as a general festive dress."

#turkic#türk kültürü#turks#turkic culture#turkish culture#turkey#central asian#muğla#Türk kıyafeti#Türk#Türkmen#Turcoman#Türkiye Türkmenleri#traditional turkish clothing

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turk beauty

#Türk#Turkic#Turkic beauty#turkmen#Turcoman#turkoman culture#turcoman jewellery#Türkler#Türk kızı#turkic world#Turkey

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pak-Turk Brotherhood ❤💚

🇹🇷🇵🇰🇦🇿

18 notes

·

View notes