#Ricardo is there in silhouette if you squint

Text

Things I didn’t expect from Aura’s playthrough; for her to sit up and go “Oh hey there-“ @ Argent

Ramblings under the cut

These were all meant to be longer but I’m still figuring out a lot and - comics aren’t a thing I can really do. I’m learning.

THINGS I LIKE before I start to muse on the nature of Aura’s bisexuality

-Aura’s speed bubbles cut her off from Argent and Ortega. This is ! Intentional. I felt clever about it.

-Light through blinds like cage/prison bars on Aura and Argent, but not Ortega.

- Argents sword at opposite angles to the bridge cables! It’s satisfying. The arm + sword should probably have like a 5° clockwise angle shift though. Argents taking up very little space in the panel but the hand/sword breaks through, she’s so imposing, suddenly, she’s breaking the border, and the bridge cables are sort of like a net around Maneater. The sword + cables behind her also box her in.

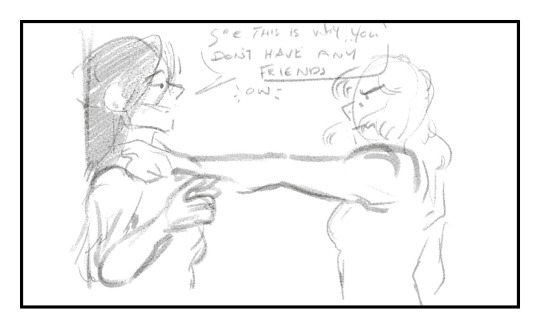

Bonus doodle for sticking with me so far

Aura and Argent are both SHORT.

Also argent gets fluffy angry ghibli hair. I think it would be funny if the hair floofed up when angry tho that’s. A bit of a dead giveaway with the nanovores- anyway———

Aura’s having fun.

She’s! A weird character to play. Mel’s a fallen hero original, Matty isn’t but he fits the world well (he’s sort of a refugee from his original setting and likes to pretend he belongs elsewhere. Aura is too (she’s. She’s his mum in basically every other au) but she plays it off better!

So the whole run is a bit more “let’s! Have fun!” Than actually. Honestly building the character thoroughly. It’s an Au of my oldest oc! My favourite girl! Hell yeah!

Plus in superhero universes she’s usually a bit of a superwoman-sort-of-a-vibe so it’s nice to see her with the gloves off being horrible. Because it does come fairly naturally to her.

But yeah! The “Maneater” moniker lends itself to ‘oooo femme fatale’ but she’s equal opportunities on the eating, she’s bi. Generally in a sort of “lmao doesn’t everybody have crushes on other girls though???” Way, she’s sorta clueless. She’s also got a heavy streak of “I’m here for a good time not a long time so I’m gonna take everything going please and thank you veeery much!” By which I mean I think Chen’s the only person she isn’t making a pass at.

She leans more to attraction towards men, but it’d be like 60/40 if I had to put numbers on it. There are universes where she has like two and a half wives, she’s out here vibing.

#fhr#fallen hero rebirth#fallen hero retribution#lady argent#fhr argent#fhr sidestep#sidestep fhr#Ricardo is there in silhouette if you squint#sadbh art#aura cross#wow I’m so sorry I talked. so much.#this isn’t even like good this is my experimental noodly shit#well this was meant to have a transparent bg#and now I feel like a fool#smh

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: In Search of Olga, Picasso’s First Wife and Muse

Pablo Picasso, “Portrait d’Olga dans un fauteuil” (1918), oil on canvas, 130 x 88.8 cm (collection of Musée national Picasso-Paris, ©RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau) (all images courtesy of Musée national Picasso-Paris)

PARIS — There’s a telling photo of Pablo Picasso and Olga Khokhlova in Rome in 1917, at the very beginning of the couple’s courtship. Picasso, flanked by the grinning woman who would soon become his first wife and his friend, the playwright Jean Cocteau, isn’t even looking at the camera. His body is turned to the side, his piercing gaze intensely fixed on Olga. You can feel the yearning burning through him. The relationship was fresh, lustful, perhaps the closest it ever came to bliss. Olga would dominate his works over the next several years, reading or holding their son Paul, yet always seeming to shy away from his scrutiny. By the end of the following decade, Picasso had shifted his attentions to another woman, but that same ferocity would return in the form of blistering depictions of Olga.

That photo, on view at the Picasso Museum as part of Olga Picasso, the first exhibit devoted to the artist’s first wife and one of his longtime muses, is remarkable for another reason: It’s one of the rare moments we see Olga smiling. Born in 1891 in Nezhin, a Ukrainian city that was then part of the Russian Empire, Olga Khokhlova joined Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1912. She left home to travel with the company in 1915, two years before the outbreak of the Russian Revolution, and she never saw her family again. Our perception of this woman rests almost solely on the prism of Picasso’s gaze and, later, his cooling affection for her.

Olga Picasso, installation view (© Musée national Picasso-Paris / photo by Philippe Fuzeau)

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky), “Ricardo Vinès, Olga et Pablo Picasso, Manuel Angeles dit Manolo Ortiz au bal du Comte de Beaumont, Hôtel de Masseran, Paris, 1924” (undated print), 20,5 x 17 cm (collection Musée national Picasso-Paris, ©RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau)

In his paintings, Olga is a constant melancholic figure: eyes averted, face partially hidden. In the pastel work “Pensive Olga” (1923), she sits with her deep, dark eyes cast down, two fingers to her temples, hair set in a severe center part, pale skin nearly overwhelmed by the blue of her dress. She assumes a nearly identical position in “Woman Reading” (1920), though the blue dress has been replaced by one of a less-stifling gray, and her attention is drawn to a letter in her hand. Her mind is clearly elsewhere; Picasso has become an outsider, seemingly unable to penetrate her thoughts, intruding on a moment of sorrow.

Pablo Picasso, “Olga pensive” (1923), pastel and black pencil on pre-sanded vellum paper, 105 x 74 cm (collection of Musée national Picasso-Paris, ©RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau)

Pablo Picasso, “Femme lisant” (1920), oil on canvas, 100 x 81,2 cm (collection Musée de Grenoble, ©Musée de Grenoble)

Olga Picasso, installation view (© Musée national Picasso-Paris / photo by Philippe Fuzeau)

The exhibit, which assembles letters, family photographs, and dance slippers alongside Picasso’s portraits, attempts to shed new light on Olga. Her tours with the Ballet Russes and her marriage to Picasso in Paris in 1918 meant that she never saw the violence of the Bolshevik revolution and the subsequent Russian civil war. Between 1917 and 1920, she lost all contact with her family. When the letters finally arrived, they brought news that Olga’s father and brothers had died fighting with the counterrevolutionary forces and that her mother Lydia and sister Nina had left for Georgia. “Life here is dreadful,” Nina wrote to her sister in 1920. “How lucky you are to have escaped.” In a letter that same year, Lydia apologizes for Nina’s plea for Olga to send money and asks her daughter to describe her daily life. We can only imagine what Olga’s responses must have been, as there are no records of her letters to her family.

Meanwhile, Olga and Pablo were rapidly climbing the societal ranks in Paris as Picasso’s fame grew. They moved to an apartment on rue La Boétie in the ritzy 8th arrondissement, enjoyed the company of Igor Stravinsky and Jean Cocteau, and went to balls thrown by Count Étienne de Beaumont.

The birth of their son Paul in 1921 marked a new phase for the couple. Picasso’s portraits of Olga in this period show a warm, tender woman utterly absorbed by the infant playing in her arms, her hefty silhouette a call to Picasso’s renewed interest in classicism. Paul’s arrival briefly united the strained couple, but it’s notable that while her body is relaxed, enveloping her son, her face is still partially turned away from the artist and tinged with sadness.

Pablo Picasso, “Mère et enfant au bord de la mer” (1921), oil on canvas, 142.9 x 172.7 cm (collection of The Art Institute of Chicago, ©Art Institute of Chicago, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image The Art Institute of Chicago)

Photomatons d’Olga et Paul Picasso, ca. 1928, silver gelatin print, 10.8 x 3.8 cm (Collection BRP)

In 1927, Picasso met Marie-Thérèse Walter, then just 17 years old. Enamored, he secretly brought her to Brittany during a family vacation and was inspired by his new mistress to create his Bathers series (1928). In the paintings, Walter was everything Olga was not: bright, aerial, erotic. With his marriage essentially over, Picasso began to eviscerate Olga in his paintings. In “Nude in a Red Armchair” (1929), her contorted limbs are splayed over the seat, her breasts dangling from her throat, her mouth open in agony. It’s a disturbing, grotesque image, a violent distortion of the woman Picasso had painted in another armchair just a decade earlier to celebrate their engagement.

While Olga’s physical manifestation filled Picasso’s earlier canvases, it’s her metaphorical presence that looms over his paintings dating after this period. Walter’s arrival as Picasso’s new muse cemented the growing rift between the couple, though they would stay legally married until her death in 1955. Recognizable by her disheveled hair, open jaw, and bared teeth, Olga appears in many of the artist’s Crucifixion scenes and even in his self-portraits, underscoring his obsessive need to continue to render her on his own terms.

Pablo Picasso, “Grand nu au fauteuil rouge” (1929), oil on canvas (collection of Musée national Picasso-Paris, ©RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau)

Pablo Picasso, “Buste de femme avec autoportrait” (1929), oil on canvas (private collection courtesy of McClain Gallery, ©Private Collection, Courtesy of McClain Gallery/ photo Alister Alexander, Camerarts)

Pablo Picasso, “La Crucifixion” (1930), oil on plywood (collection of Musée national Picasso-Paris, ©RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau)

Yet the Olga we see through Picasso’s paintings is markedly different from the one we glimpse in home movies from around 1930. In one of the exhibit’s few documentations of Olga that isn’t directly colored by her husband’s gaze, she smiles and plays with the family dogs in a garden, picks petals off a flower, and squints at the camera, her hand raised to block out the sun. She appears both shy and eager to win over the viewer. And, for just a few minutes, she exudes a sense of delight and openness that we never get to see elsewhere.

Pablo Picasso, “Olga Khokhlova à la mantille” (1917), oil on canvas, 64 x 53 cm, collection Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, © Photo: Equipo Gasull)

Olga Picasso, installation view (© Musée national Picasso-Paris / photo by Philippe Fuzeau)

Olga Picasso continues at the Musée National Picasso (5 rue de Thorigny, Paris) through September 3.

The post In Search of Olga, Picasso’s First Wife and Muse appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2pWyXuj

via IFTTT

0 notes