#Quentin Durward

Photo

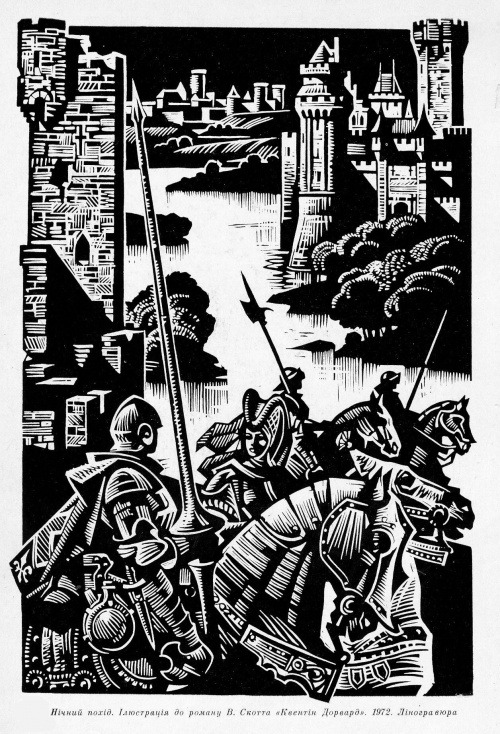

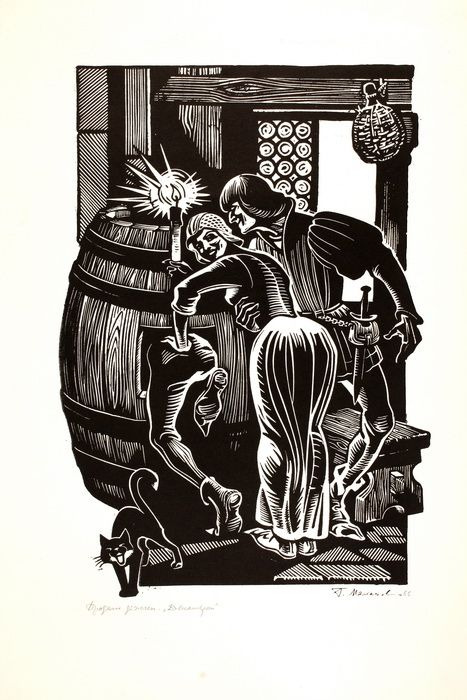

Heorhiy Malakov`s illustration to Quentin Durward by Walter Scott, 1972

#Quentin Durward#Walter Scott#knight#Ukrainian art#Heorhiy Malakov#Ukrainian graphic#linogravure#vintage book illustration#1970s

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

Janvier 1966

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quentin Durward est un roman historique écrit par l'écrivain écossais Sir Walter Scott.

0 notes

Video

Judge Quentin D. Corley (LOC) by The Library of Congress

Via Flickr:

Bain News Service,, publisher. Judge Quentin D. Corley [between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915] 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Notes: Title from unverified data provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards. Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress). Format: Glass negatives. Rights Info: No known restrictions on publication. Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print General information about the Bain Collection is available at hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.ggbain Higher resolution image is available (Persistent URL): hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.13513 Call Number: LC-B2- 2752-12

#Library of Congress#dc:identifier=http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.13513#xmlns:dc=http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/#automobiles#driving#steering wheel#artificial arm#artificial limbs#Judge#Quentin D. Corley#Dallas#Texas#prosthesis#amputees#1916#Corley#Quentin Durward Corley#handicapped#disabled#George Grantham Bain#Bain News Service#glass negatives#vehicle#judge quentin corley#car#suits#20s#city#on atm#early automobile

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland" is a poem by the Ukrainian writer Lesya Ukrainka, written in 1893. When creating the poem, the writer notes facts that can't be found in the works of other writers (such as Walter Scott or Robert Burns) and somewhat intersperses certain historical facts to give the work a more heroic sound. Thus, highlighting the struggle of the Scottish people for their independence, Lesya Ukrainka draws a parallel with the Ukrainian people, who also suffer from oppression (at that time by the Russian Empire).

And perhaps I would never have paid attention to this work if it were not for the linocut of the Ukrainian graphic artist Heorhiy Malakov. I saw this very work in my childhood at my grandparents' country house. Looking at me from the wall of a half-darkened room, wrapped in the smell of dampness, this knight, unknown to me at the time, frightened me considerably (the glint on the lying glove always reminded me of a blade instead of a finger). It's interesting to watch how our childhood fears dissipate over time.

Night hike. Illustration for W. Scott's novel Quentin Durward, 1972.

Malakov was very fond of the theme of chivalry and piracy, often depicting courtly scenes, feasts, entertainment and various funny skits. He also made illustrations for Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, in the characters of which he reflected not only the cheerful mood of the stories themselves, but also his own life-loving nature.

Selling barrel. Based on the Decameron by J. Boccaccio, 1966.

I spent insane amount of time photoshopping cover picture, but the colors are still weird e_e

Game: The Sims 4

CC credits:

Horse: Knight Set by @objuct, reins are photoshopped.

Knight: Chainmail Coif by @simmiev2 | Generic City Guard Armor by @notsooldmadcatlady | Sherri Cape by MSSIMS | Shoulder pads from FF XIV Innocence set by plazasims

P.S. My inner 'designer' died on that cover picture.

#sims#the sims 4#sims 4#ts4#sims 4 historical#sims 4 medieval#ts4 medieval#ukrainian art#graphic art#українське мистецтво#графіка

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am super late to discussion of character descriptions in fanfic, but I want to contribute.

My Immortal-style long descriptions of how characters look like may be more prevalent in fanfiction than in published literature nowadays, and the reason may be the fact that fanfic writers consume more visual media than literature, but it's not inherent to fanfic and didn't start because of cinema.

I am re-reading Quentin Durward right now, and immediately after the historical introduction it has two pages long description of how protagonist looks like. And it was published in 1823, just a year after the first ever photograph was made.

(If anything I feel like fiction became less descriptive after cinema became widespread. Not saying that it's connected in any way though).

--

I think the biggest change is that fiction has gotten less wordy and convoluted over time. Flowery descriptions of visuals are probably just a casualty of that.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knights of the Round Table 1953

First MGM film to be shot in CinemaScope.

Robert Taylor was never comfortable filming these types of movies. He often referred to them as "iron jockstrap" movies and actually preferred doing westerns.

Knights of the Round Table was the second in an unofficial trilogy. The other two movies were Ivanhoe and The Adventures of Quentin Durward. The three movies were made by producer Pandro S. Berman and director Richard Thorpe. Robert Taylor starred in all three movies.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕷𝖔𝖚𝖎𝖘 𝖃𝕴

...I finished reading "Quentin Durward" by Walter Scott a couple of months ago and still under the impression; the book definitely had me on the edge of my seat! I can't believe, it has been in my library for years! And when I took the book off the shelf, I didn't know how much I would fall in love with the main character, now my most favourite historical figure -- King of France, Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (Ludwig XI der Klüge, in German).

⬆ a 19th century portrait is from brianrxm.com .....right from the very first pages I felt an ever-increasing sympathy to the king, not even knowing yet, by the author's intention, who that person really was...

"A cunning diplomat and a bold warrior" -encyclopedia britannica, - the brilliant monarche, Louis XI, was a person of outstanding intellect and an unsurpassed master of intrigue what earned him another nickname -- "The Universal Spider." His plans and decisions were always thoroughly thought through. And whatever he did served a higher purpose that he finally achieved at the end of his life -- building up the fractured and turbulent provinces into powerful, unified France. He never gave up, converting even painful failures into triumphant success.

Though he always preferred consilium whenever there was a chance to avoid bloodshed, he was fearlessly brave when he had to personally take part in armed conflicts.

Louis XI did appreciate those who were loyal to him. Also, he never left his enemies unpunished. And, even so, it was never for the sheer enjoyment at the sight of one's torments, as it was for the majority of his mighty contemporaries, but as acts of fair retribution only.

⬆ image from meisterdrucke.at .....Louis XI did many other significant things as well, like opening manufactures, supporting crafts, developing book-printing, and much more.

I also love his sarcastic style of humour as it appears in "Quentin Durward."😎

During my so called on-line investigations, I found out that many classic sources were actually unfair to Louis XI traditionally describing him as mainly ruthless and insidious person, in fact magnifying and even thinking up certain negative aspects that ostensibly might be part of his nature, as well as downplaying his indisputable strengths. Yet it was not least exactly those tough traits of his character that saved him his life many times and led him to his impressive achievements.

With all this, everything smart and worthy of admiration that I come to know about Louis XI either overweighs, or justifies or explains in some way those deeds of his that can't be considered as kind ones.

*.·:·.✧ ✦ ✧.·:·.*

“𝘞𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘥𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘶𝘮𝘱𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘸𝘢𝘭𝘬 𝘣𝘦𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘦, 𝘴𝘩𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘭𝘰𝘴𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘭𝘭𝘰𝘸 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘤𝘭𝘰𝘴𝘦𝘭𝘺.” — Louis XI of France

⬆ Ludwig XI. (1423-83) König von Frankreich von Nicolas II de Larmessin

...I have also come across a web site meisterdrucke.at where you can choose from their vast collection of portraits of prominent people of the centuries gone by, and then you have an option to choose a frame and a canvas material for the portrait to be printed on... isn't that cool?! ...It's been a long time since I wanted to have a portrait of an inspiring historical figure on our home library wall, and now I have no doubts as to who it has to be!

......Actually, I have another favourite character in this book (surprisingly, not the main hero, Quentin Durward, in spite of his high (and sometimes even overhigh moral qualities)) which is a gypsy man, Hairaddin... who knew too much and participated directly in too many ventures that it was inevitable for him but to come to a bad end... I was nearly crying for him when reading about his last moments (yeah, I'm a cry baby when it comes to sad books or movies - and that's why I usually avoid such stuff, - and it doesn't matter if the story happened 600 years ago:) But thanks to Walter Scott, he softened the passage about his unhappy ending just by leaving it to the readers' imagination...

Of course, this humble post is only to convey just a little bit of my feelings for my king and share some initial information that I'd dug up so far. Since I'm eager to know about Louis XI as much as posible, I've searched for some great books about him and ended up with this unfortunately small list 📖:

The Spider King by Lawrence Schoonover

Louis XI. The Universal Spider by Paul Murray Kendall

Chant Royal. The Life of Louis XI, King of France by James Cleugh

The Memoirs by Philip de Commines

There're many more books about Louis XI, but they are all in french...🤔

📺 I was also surprised to find out that there's a film - Louis XI: Shattered Power (2011), with Jacques Perrin in the lead role, - in my nearest must-watch list!

📺 There is another film I'd like to watch because of Louis XI who was portrayed by Harry Davenport - "The Hunchback of Notre Dame", 1939

So... this exciting and thought-provoking book definitely goes to my most favs! It will certainly keep you intrigued, and you'll experience a variety of feelings while being entertained with wise and witty dialogues between the characters throughout the whole story...⚜️

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

You make me want to read Scott.

Dear Anon, you've made me and my 13-year-old self very happy. Based solely on personal experience, I recommend Ivanhoe as a starter Scott novel. It has rich atmosphere, good pacing, plenty of adventure and romance, and a gratuitous drinking contest, as well as a cameo from everyone's favorite outlaw. If trying the long poems (Lady of the Lake, Marmion,) my counsel is to give yourself time to settle into them, and be rewarded with saying to yourself 'Oh that's where that line comes from' at frequent intervals. Also, as the allusion in Dracula makes clear, Marmion is unhinged in the best way.

Also also... if anyone wants to do another medievalism readalong, I'd be up for doing The Talisman (though the Orientalism is absolutely wild in that one) or Quentin Durward (in which Scott decides to write about court intrigue in 15th-century France.)

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

EN EXCLUSIVITÉ : Pour celles et ceux qui apprécient les faits historiques et culturels, j'ai trouvé la seule image échappée de la destruction de la pellicule originale du film à jamais disparu — « Quentin Durward » — réalisé en 1912 par Adrien Caillard : https://www.guyboulianne.info/2022/09/26/en-exclusivite-un-cliche-unique-de-la-pellicule-originale-du-film-a-jamais-disparu-quentin-durward-realise-en-1912-par-adrien-caillard

0 notes

Photo

An Oxford Dialoguing

An Oxford Dialoguing;

ON one of those bright misty days at Oxford, when the grey towers are dimly seen rising from masses of amber and russet foliage, when reading men enjoy a brisk walk in the keen afternoon air, to talk over the feats of the Long and the chances of the coming Schools, a tutor and a freshman were striding round the meadows of Christ Church. The Reverend ^Ethelbald Wessex, called by undergraduates ‘the Venerable Bede,’ was taking a tutorial grind with his young friend, Philibert Raleigh, who had come up from Eton with a brilliant record. The Admirable Crichton, as Phil was named by his admirers, was expected to do great things in the History School: his essay had won him the scholarship, and even the Master admitted that he had read some which were worse. Phil was enlarging on the lectures of the new Regius Professor.

‘ We are in luck,’ said he, ‘ to be reading for the Schools at a time when the Professor is one of the first of living writers; his lectures are a lesson in English literature private sofia tours, instead of a medley of learned “ tips.” ’

‘ I hope my dear boy,’ said the Venerable, ‘that you are not referring to the late Professor in that rather superficial remark of yours, for he was certainly one of the most con-summate historians of modern times.’

Fortnightly Review, vol. 54, N.S. October 1893.

‘ Oh, no,’ said Phil, in an apologetic tone; ‘ I never heard Dr. Freeman lecture at all, and I have not yet finished the third volume of The Norman Conquest. But surely he is hardly in it as a writer with Froude, whose history one enjoys to read as one enjoys Quentin Durward or Ivanhoe f ’

‘You are giving yourself away, dear boy,’ replied the tutor, with his shrewd smile, ‘ when you class the History of England with a novel. Mr. Froude’s enemies (and I am certainly not one of them) have never said worse of him than that. I am afraid that the first thing which Oxford will have to teach you is that the business of a historian is to write history, not romance.’

‘ Of course,’ said the freshman, a little put out by the snub, ‘ I should not compare the History of England to romance, nor, I suppose, do you. But we know that all the histories in the world which have permanent life are composed with literary genius, and are delightful to read in themselves. A great historian has to write history, but he also has to write a great book.’

Literature is one thing

‘ Literature is one thing,’ said the Venerable, in some-what oracular tones, ‘ and history is another thing. The TCXO? of history is Truth. She may be more attractive to some minds when clothed in shining robes; but the historian has to worship at the shrine of nuda Veritas, and it is no business of his to care for the drapery she wears. What I mean is, that history implies indefatigable research into recorded facts. That is the essence: the form is mere accident.’

‘ The form of the sentences may be a secondary thing,’ pleaded the Crichton, ‘but, surely, the vivid power of striking home which marks every great book is essential to a history intended to survive. Would the Master have given all that labour to Thucydides if the whole of his

work had been occupied with monotonous accounts of how the Spartans marched into Attica, and how the Athenians sent seven ships to the coast of Thrace? Thucydides is because of the elaborate speeches, the account of the plague, the civil war in Corcyra, the siege of Syracuse, and the last sea-fight in the harbour. These are the things which make Thucydides immortal, and remind one of the messenger’s speech in the Persce. It is these magnificent pictures of the ancient world which help us to get over the wearisome parade of hoplites and sling-men, and battles of frogs and mice in obscure bays.’

This will never do,’ replied the tutor. ‘ We shall quite despair of your class, if you begin by calling “wearisome” any fact ascertainable in recorded documents. The busi-ness of the historian is to examine the evidence for what has ever happened in any place or time; and nothing which is true can be wearisome to the really historical mind.’

0 notes

Photo

An Oxford Dialoguing

An Oxford Dialoguing;

ON one of those bright misty days at Oxford, when the grey towers are dimly seen rising from masses of amber and russet foliage, when reading men enjoy a brisk walk in the keen afternoon air, to talk over the feats of the Long and the chances of the coming Schools, a tutor and a freshman were striding round the meadows of Christ Church. The Reverend ^Ethelbald Wessex, called by undergraduates ‘the Venerable Bede,’ was taking a tutorial grind with his young friend, Philibert Raleigh, who had come up from Eton with a brilliant record. The Admirable Crichton, as Phil was named by his admirers, was expected to do great things in the History School: his essay had won him the scholarship, and even the Master admitted that he had read some which were worse. Phil was enlarging on the lectures of the new Regius Professor.

‘ We are in luck,’ said he, ‘ to be reading for the Schools at a time when the Professor is one of the first of living writers; his lectures are a lesson in English literature private sofia tours, instead of a medley of learned “ tips.” ’

‘ I hope my dear boy,’ said the Venerable, ‘that you are not referring to the late Professor in that rather superficial remark of yours, for he was certainly one of the most con-summate historians of modern times.’

Fortnightly Review, vol. 54, N.S. October 1893.

‘ Oh, no,’ said Phil, in an apologetic tone; ‘ I never heard Dr. Freeman lecture at all, and I have not yet finished the third volume of The Norman Conquest. But surely he is hardly in it as a writer with Froude, whose history one enjoys to read as one enjoys Quentin Durward or Ivanhoe f ’

‘You are giving yourself away, dear boy,’ replied the tutor, with his shrewd smile, ‘ when you class the History of England with a novel. Mr. Froude’s enemies (and I am certainly not one of them) have never said worse of him than that. I am afraid that the first thing which Oxford will have to teach you is that the business of a historian is to write history, not romance.’

‘ Of course,’ said the freshman, a little put out by the snub, ‘ I should not compare the History of England to romance, nor, I suppose, do you. But we know that all the histories in the world which have permanent life are composed with literary genius, and are delightful to read in themselves. A great historian has to write history, but he also has to write a great book.’

Literature is one thing

‘ Literature is one thing,’ said the Venerable, in some-what oracular tones, ‘ and history is another thing. The TCXO? of history is Truth. She may be more attractive to some minds when clothed in shining robes; but the historian has to worship at the shrine of nuda Veritas, and it is no business of his to care for the drapery she wears. What I mean is, that history implies indefatigable research into recorded facts. That is the essence: the form is mere accident.’

‘ The form of the sentences may be a secondary thing,’ pleaded the Crichton, ‘but, surely, the vivid power of striking home which marks every great book is essential to a history intended to survive. Would the Master have given all that labour to Thucydides if the whole of his

work had been occupied with monotonous accounts of how the Spartans marched into Attica, and how the Athenians sent seven ships to the coast of Thrace? Thucydides is because of the elaborate speeches, the account of the plague, the civil war in Corcyra, the siege of Syracuse, and the last sea-fight in the harbour. These are the things which make Thucydides immortal, and remind one of the messenger’s speech in the Persce. It is these magnificent pictures of the ancient world which help us to get over the wearisome parade of hoplites and sling-men, and battles of frogs and mice in obscure bays.’

This will never do,’ replied the tutor. ‘ We shall quite despair of your class, if you begin by calling “wearisome” any fact ascertainable in recorded documents. The busi-ness of the historian is to examine the evidence for what has ever happened in any place or time; and nothing which is true can be wearisome to the really historical mind.’

0 notes

Photo

An Oxford Dialoguing

An Oxford Dialoguing;

ON one of those bright misty days at Oxford, when the grey towers are dimly seen rising from masses of amber and russet foliage, when reading men enjoy a brisk walk in the keen afternoon air, to talk over the feats of the Long and the chances of the coming Schools, a tutor and a freshman were striding round the meadows of Christ Church. The Reverend ^Ethelbald Wessex, called by undergraduates ‘the Venerable Bede,’ was taking a tutorial grind with his young friend, Philibert Raleigh, who had come up from Eton with a brilliant record. The Admirable Crichton, as Phil was named by his admirers, was expected to do great things in the History School: his essay had won him the scholarship, and even the Master admitted that he had read some which were worse. Phil was enlarging on the lectures of the new Regius Professor.

‘ We are in luck,’ said he, ‘ to be reading for the Schools at a time when the Professor is one of the first of living writers; his lectures are a lesson in English literature private sofia tours, instead of a medley of learned “ tips.” ’

‘ I hope my dear boy,’ said the Venerable, ‘that you are not referring to the late Professor in that rather superficial remark of yours, for he was certainly one of the most con-summate historians of modern times.’

Fortnightly Review, vol. 54, N.S. October 1893.

‘ Oh, no,’ said Phil, in an apologetic tone; ‘ I never heard Dr. Freeman lecture at all, and I have not yet finished the third volume of The Norman Conquest. But surely he is hardly in it as a writer with Froude, whose history one enjoys to read as one enjoys Quentin Durward or Ivanhoe f ’

‘You are giving yourself away, dear boy,’ replied the tutor, with his shrewd smile, ‘ when you class the History of England with a novel. Mr. Froude’s enemies (and I am certainly not one of them) have never said worse of him than that. I am afraid that the first thing which Oxford will have to teach you is that the business of a historian is to write history, not romance.’

‘ Of course,’ said the freshman, a little put out by the snub, ‘ I should not compare the History of England to romance, nor, I suppose, do you. But we know that all the histories in the world which have permanent life are composed with literary genius, and are delightful to read in themselves. A great historian has to write history, but he also has to write a great book.’

Literature is one thing

‘ Literature is one thing,’ said the Venerable, in some-what oracular tones, ‘ and history is another thing. The TCXO? of history is Truth. She may be more attractive to some minds when clothed in shining robes; but the historian has to worship at the shrine of nuda Veritas, and it is no business of his to care for the drapery she wears. What I mean is, that history implies indefatigable research into recorded facts. That is the essence: the form is mere accident.’

‘ The form of the sentences may be a secondary thing,’ pleaded the Crichton, ‘but, surely, the vivid power of striking home which marks every great book is essential to a history intended to survive. Would the Master have given all that labour to Thucydides if the whole of his

work had been occupied with monotonous accounts of how the Spartans marched into Attica, and how the Athenians sent seven ships to the coast of Thrace? Thucydides is because of the elaborate speeches, the account of the plague, the civil war in Corcyra, the siege of Syracuse, and the last sea-fight in the harbour. These are the things which make Thucydides immortal, and remind one of the messenger’s speech in the Persce. It is these magnificent pictures of the ancient world which help us to get over the wearisome parade of hoplites and sling-men, and battles of frogs and mice in obscure bays.’

This will never do,’ replied the tutor. ‘ We shall quite despair of your class, if you begin by calling “wearisome” any fact ascertainable in recorded documents. The busi-ness of the historian is to examine the evidence for what has ever happened in any place or time; and nothing which is true can be wearisome to the really historical mind.’

0 notes

Photo

An Oxford Dialoguing

An Oxford Dialoguing;

ON one of those bright misty days at Oxford, when the grey towers are dimly seen rising from masses of amber and russet foliage, when reading men enjoy a brisk walk in the keen afternoon air, to talk over the feats of the Long and the chances of the coming Schools, a tutor and a freshman were striding round the meadows of Christ Church. The Reverend ^Ethelbald Wessex, called by undergraduates ‘the Venerable Bede,’ was taking a tutorial grind with his young friend, Philibert Raleigh, who had come up from Eton with a brilliant record. The Admirable Crichton, as Phil was named by his admirers, was expected to do great things in the History School: his essay had won him the scholarship, and even the Master admitted that he had read some which were worse. Phil was enlarging on the lectures of the new Regius Professor.

‘ We are in luck,’ said he, ‘ to be reading for the Schools at a time when the Professor is one of the first of living writers; his lectures are a lesson in English literature private sofia tours, instead of a medley of learned “ tips.” ’

‘ I hope my dear boy,’ said the Venerable, ‘that you are not referring to the late Professor in that rather superficial remark of yours, for he was certainly one of the most con-summate historians of modern times.’

Fortnightly Review, vol. 54, N.S. October 1893.

‘ Oh, no,’ said Phil, in an apologetic tone; ‘ I never heard Dr. Freeman lecture at all, and I have not yet finished the third volume of The Norman Conquest. But surely he is hardly in it as a writer with Froude, whose history one enjoys to read as one enjoys Quentin Durward or Ivanhoe f ’

‘You are giving yourself away, dear boy,’ replied the tutor, with his shrewd smile, ‘ when you class the History of England with a novel. Mr. Froude’s enemies (and I am certainly not one of them) have never said worse of him than that. I am afraid that the first thing which Oxford will have to teach you is that the business of a historian is to write history, not romance.’

‘ Of course,’ said the freshman, a little put out by the snub, ‘ I should not compare the History of England to romance, nor, I suppose, do you. But we know that all the histories in the world which have permanent life are composed with literary genius, and are delightful to read in themselves. A great historian has to write history, but he also has to write a great book.’

Literature is one thing

‘ Literature is one thing,’ said the Venerable, in some-what oracular tones, ‘ and history is another thing. The TCXO? of history is Truth. She may be more attractive to some minds when clothed in shining robes; but the historian has to worship at the shrine of nuda Veritas, and it is no business of his to care for the drapery she wears. What I mean is, that history implies indefatigable research into recorded facts. That is the essence: the form is mere accident.’

‘ The form of the sentences may be a secondary thing,’ pleaded the Crichton, ‘but, surely, the vivid power of striking home which marks every great book is essential to a history intended to survive. Would the Master have given all that labour to Thucydides if the whole of his

work had been occupied with monotonous accounts of how the Spartans marched into Attica, and how the Athenians sent seven ships to the coast of Thrace? Thucydides is because of the elaborate speeches, the account of the plague, the civil war in Corcyra, the siege of Syracuse, and the last sea-fight in the harbour. These are the things which make Thucydides immortal, and remind one of the messenger’s speech in the Persce. It is these magnificent pictures of the ancient world which help us to get over the wearisome parade of hoplites and sling-men, and battles of frogs and mice in obscure bays.’

This will never do,’ replied the tutor. ‘ We shall quite despair of your class, if you begin by calling “wearisome” any fact ascertainable in recorded documents. The busi-ness of the historian is to examine the evidence for what has ever happened in any place or time; and nothing which is true can be wearisome to the really historical mind.’

0 notes