#No Context Crow No. 284

Text

No Context Crow #284: Quilted Crow

Found here.

#crows#corvids#corvidae#birds#animals#art#arts n crafts#arts and crafts#quilt#quilting#textile art#quiltblr#fabric art#fall#autumn#fall aesthetic#autumn aesthetic#daily crows#crow queue#No Context Crow No. 284

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application 5: Gender and Sexuality and "The Sandman"

Gender Performativity

Definition: Central to Butler's gender theory, gender performativity posits that gender is not an inherent trait but rather a repeated performance that creates the illusion of a stable identity. Through acts of expression and embodiment, individuals continually produce and negotiate their gender within social contexts, challenging fixed notions of masculinity and femininity. Butler particularly cites drag as an example of gender performance through participation in gendered acts (1).

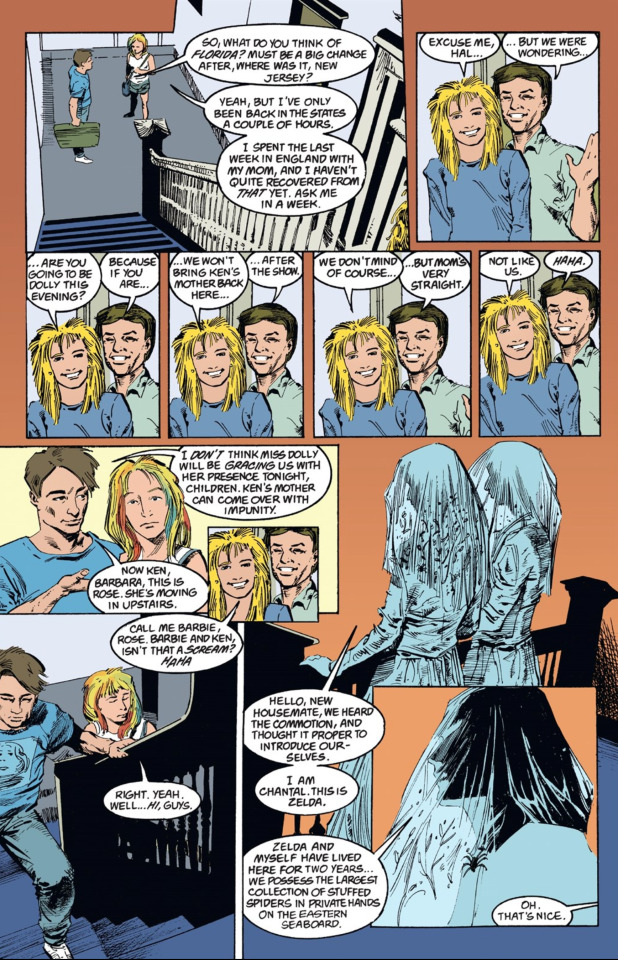

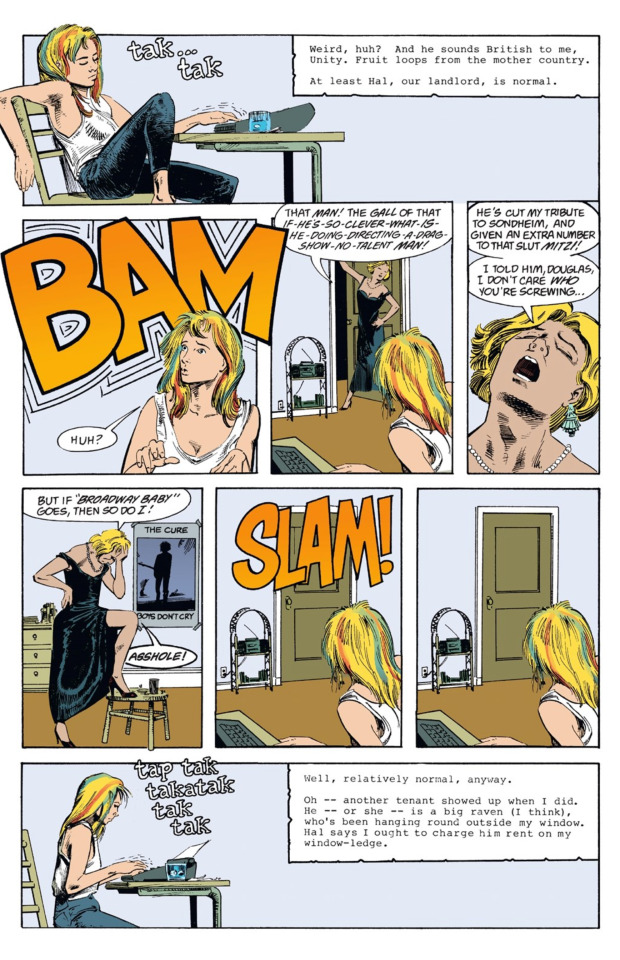

Gaiman, 279 & 284

Hal's transformation into Dolly in the chapter “Moving In” exemplifies Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity. As Hal assumes the persona of Dolly, he consciously engages in gendered acts that subvert traditional notions of masculinity and femininity. By donning a short blonde wig, a shining black dress, along with various accessories, Hal/Dolly actively constructs a new, gendered persona for himself outside of his own day to day identity. Through his drag performance, Hal disrupts the idea of a stable and fixed gender identity, highlighting the fluidity and performativity of gender. Dolly's flamboyant and dramatic demeanor contrasts with Hal's persona when initially showing Rose around the house, showcasing the multiplicity of gender expressions within a single individual. This duality underscores Butler's assertion that gender is not an inherent trait but rather a product of repeated performances within social contexts.

Hal's embrace of his drag persona challenges societal expectations and norms surrounding gender, illustrating the potential for subversion and resistance within gender performativity. By participating in drag, Hal/Dolly navigates and negotiates the complexities of gender, offering a glimpse into the constructed nature of identity. Through his performance, Hal/Dolly not only entertains but also disrupts dominant narratives, opening up possibilities for alternative expressions of gender beyond the confines of the sex/gender binary. Overall, Hal's portrayal as both a "normal" landlord and a drag persona highlights the intricate interplay between performance, identity, and social context in shaping notions of gender. His embodiment of Dolly exemplifies Butler's concept of gender performativity, challenging viewers to reconsider and expand their understanding of gender beyond traditional binaries.

Scopophilia

Definition: Derived from Mulvey's psychoanalytic film theory, scopophilia refers to the pleasure derived from looking and being looked at (2). In her work, Mulvey discusses how cinema often caters to the male gaze, objectifying women as passive objects of desire, thus perpetuating patriarchal norms through visual consumption (3).

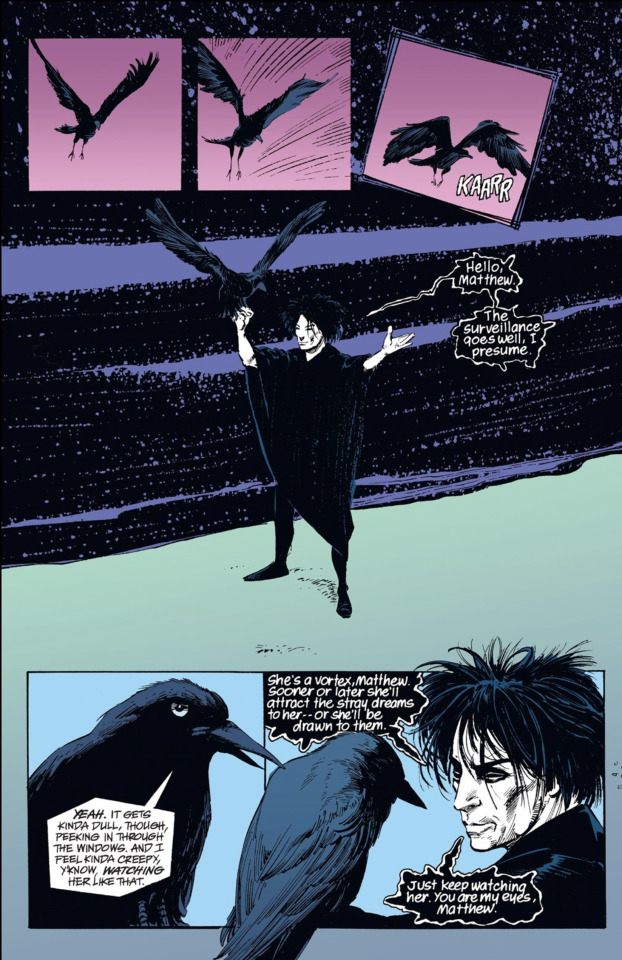

Gaiman, 286

In the same chapter, we witness Dream, a masculine-presenting Endless, spying on and gathering information about the Vortex, Rose through his trusty crow Matthew. This scene encapsulates the aforementioned definition of scopophilia quite well. As Dream observes Rose from afar, he not only indulges in the act of looking but also derives a sense of pleasure and control from his voyeuristic gaze. Through Matthew's perspective, Dream objectifies Rose, reducing her to a passive object of desire. Mulvey's theory of scopophilia emphasizes the power dynamics inherent in the act of looking, particularly within the context of patriarchal structures. Dream's observation of Rose reflects a form of visual consumption that aligns with the male gaze, reinforcing traditional gender roles and perpetuating societal norms of objectification. By positioning Rose as the object of his gaze, Dream asserts his dominance and reinforces his own agency while diminishing Rose's autonomy.

Furthermore, the use of Matthew as a conduit for Dream's voyeuristic gaze adds another layer to the scene. As a supernatural entity, Matthew embodies a certain detachment and otherness, allowing Dream to distance himself from the consequences of his actions. This amplifies the sense of control and power that Dream derives from his observation of Rose, reinforcing the dynamics of scopophilia within the narrative. This scene serves as a poignant example of how the male gaze operates within visual media. Through his voyeuristic gaze, Dream perpetuates patriarchal norms of objectification, reinforcing his dominance and control over Rose. Mulvey's concept of scopophilia provides a framework for understanding the power dynamics at play in this scene, highlighting the complexities of gendered representation and visual consumption within "The Sandman" narrative.

Gender Norms

Definition: Gender norms are societal expectations and standards dictating the behaviors, roles, and attributes deemed appropriate for individuals based on their perceived gender. These norms shape how people express themselves, interact with others, and navigate various social contexts. Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity emphasizes how gender norms are not inherent but are instead constructed and maintained through repeated performances of gendered behaviors (4).

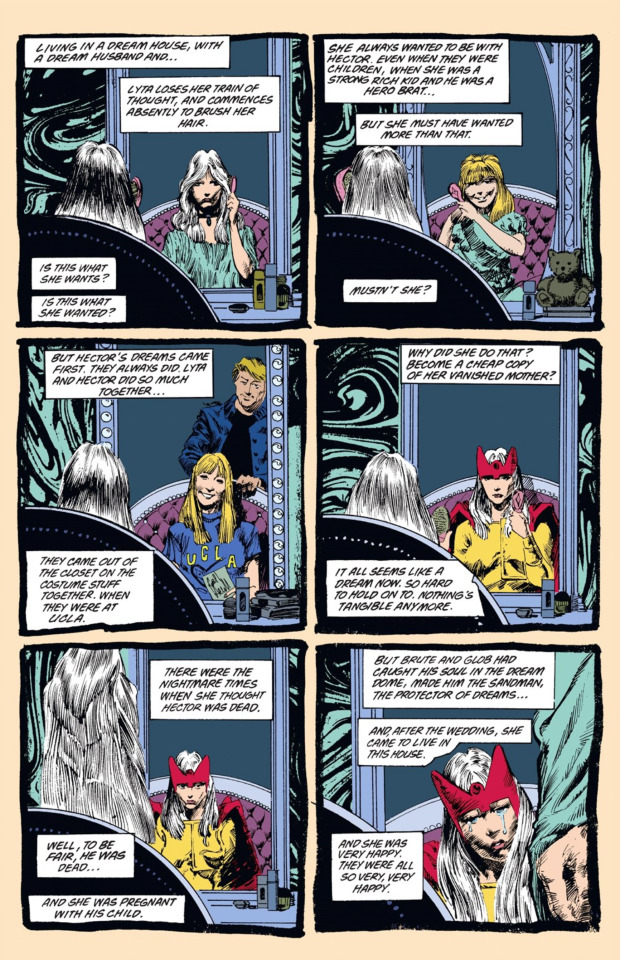

Gaiman, 309-310

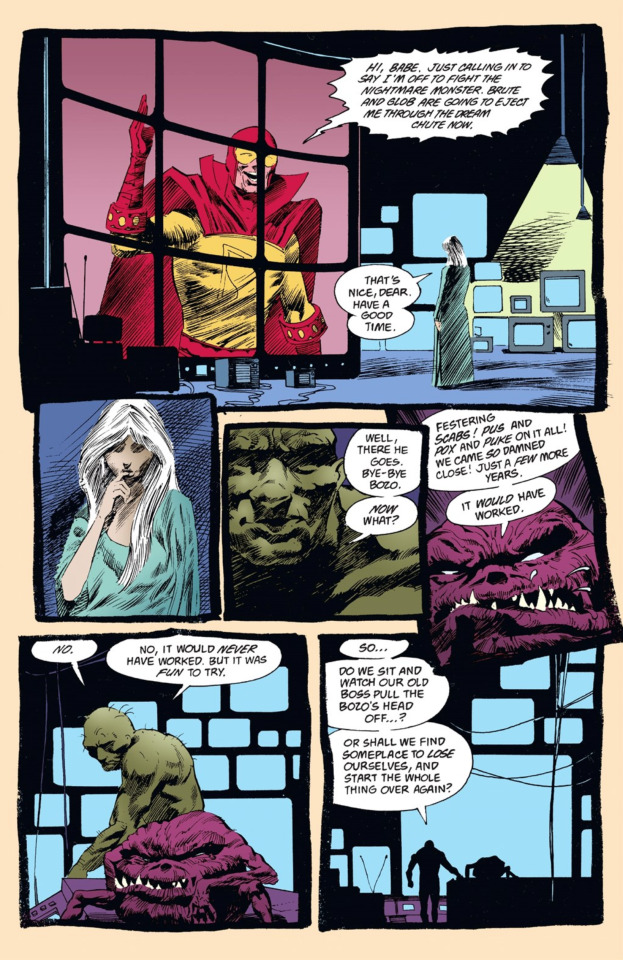

In "The Sandman: Book One," the character of Lyta Hall exemplifies the challenges posed by societal gender norms, particularly in the chapter "Playing House." As she grapples with her role in the Dream World alongside her husband, Hector, also known as the Sandman, Lyta finds herself confined by traditional expectations of femininity and motherhood. Lyta's portrayal as the doting wife and expectant mother reflects the gender norms that dictate women's roles within patriarchal societies. Despite her desires and aspirations outside of the domestic sphere (which she can barely think about without her mind going blank), Lyta feels compelled to prioritize her relationship with Hector and fulfill the duties expected of her as a partner. This internal conflict underscores the pressure individuals face to conform to predefined gender roles, even within fantastical realms like the Dream World.

Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity offers insight into Lyta's struggles, highlighting how societal expectations shape and constrain individuals' performances of gender. Lyta's adherence to traditional gender norms is not a reflection of her inherent identity but rather a result of the social conditioning that dictates her behavior within the Dream World. Her reluctance to challenge these norms stems from the fear of deviating from societal expectations and facing potential consequences. Furthermore, Lyta's experience can serve as a critique of the limitations imposed by gender norms, particularly on women's autonomy and agency. Despite her apparent dissatisfaction with her role, Lyta feels obligated to maintain the facade of the dutiful wife and mother, calling Hector “Dear” and telling him to “have a good time” (Gaiman, 310) during his upcoming fihgt, highlighting the coercive nature of gender expectations. Her story reflects the broader struggle for gender equality and the need to challenge and redefine traditional notions of femininity and masculinity in order to create more inclusive and equitable societies.

Subversion

Definition: Rooted in hooks' intersectional feminist theory, subversion involves challenging and destabilizing oppressive power structures. hooks emphasizes the importance of resistance and transformative practices that disrupt dominant narratives of race, gender, and class, fostering empowerment and liberation for marginalized groups (5).

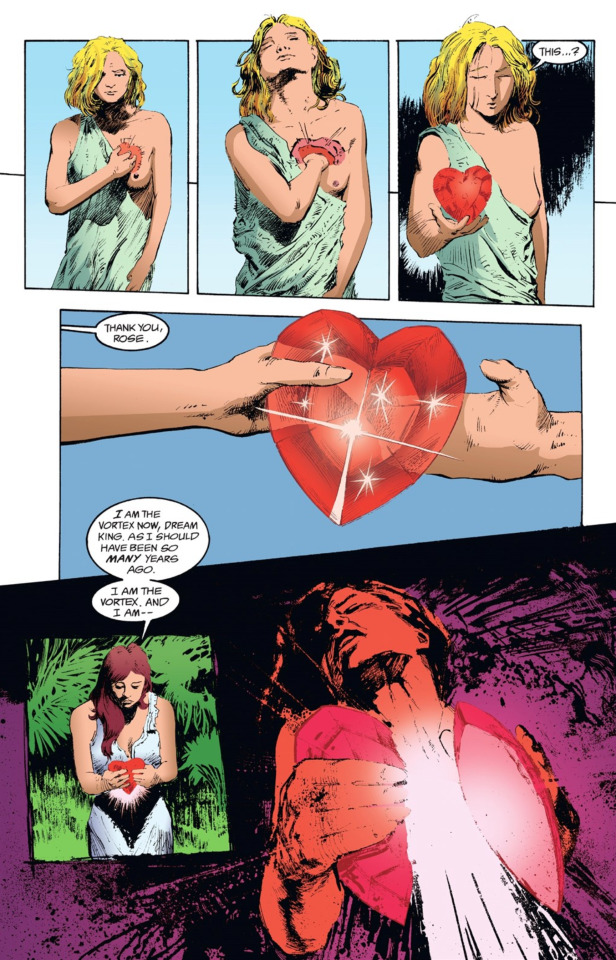

Gaiman, 429

In the scene where Unity confronts Dream in the chapter "Lost Hearts," the concept of subversion, as articulated by bell hooks, is vividly portrayed. Unity's act of challenging Dream's authority and disrupting the narrative he has constructed serves as a powerful example of resisting oppressive power structures. Dream, as a powerful and authoritative figure with control of the Dream World, represents a dominant narrative that imposes control and dictates the lives of others. Unity's decision to confront him directly and refuse to adhere to his decision to kill Rose represents a direct challenge to his power and control. Unity disrupts the established order and asserts her agency. Unity's actions speak to hooks’ words on transformative practices, as she seeks to dismantle the oppressive power dynamics that govern the Dream World. Her willingness to sacrifice herself in order to protect Rose demonstrates a commitment to challenging injustice and fostering empowerment.

hooks' emphasis on resistance and transformative practices is reflected in Unity's actions, as she actively works to destabilize the power dynamics at play. Rather than succumbing to the role assigned to her granddaughter by Dream, Unity chooses to rewrite her own narrative. In doing so, she embodies the spirit of subversion by choosing her own path and carrying on her legacy through her granddaughter. Overall, the scene where Unity confronts Dream in "Lost Hearts" can be viewed as a metaphorical example of the concept of subversion as defined by bell hooks. Through her defiance and refusal to conform to dictated norms, Unity challenges dominant narratives and paves the way for Rose’s freedom.

Sex/Gender Binary

Definition: The sex/gender binary is a societal framework that categorizes individuals into two distinct and mutually exclusive categories: male and female. It presumes a fixed alignment between biological sex and gender identity, neglecting the diversity of sex characteristics and gender identities that exist beyond this binary classification. While she doesn’t address the binary directly, Judith Butler's critique of the sex/gender binary challenges the idea that sex and gender are naturally or inevitably linked. Her work encourages a reexamination of the assumptions underlying the sex/gender binary, advocating for a more inclusive understanding of sex and gender that acknowledges their fluidity and complexity.

Gaiman, 438

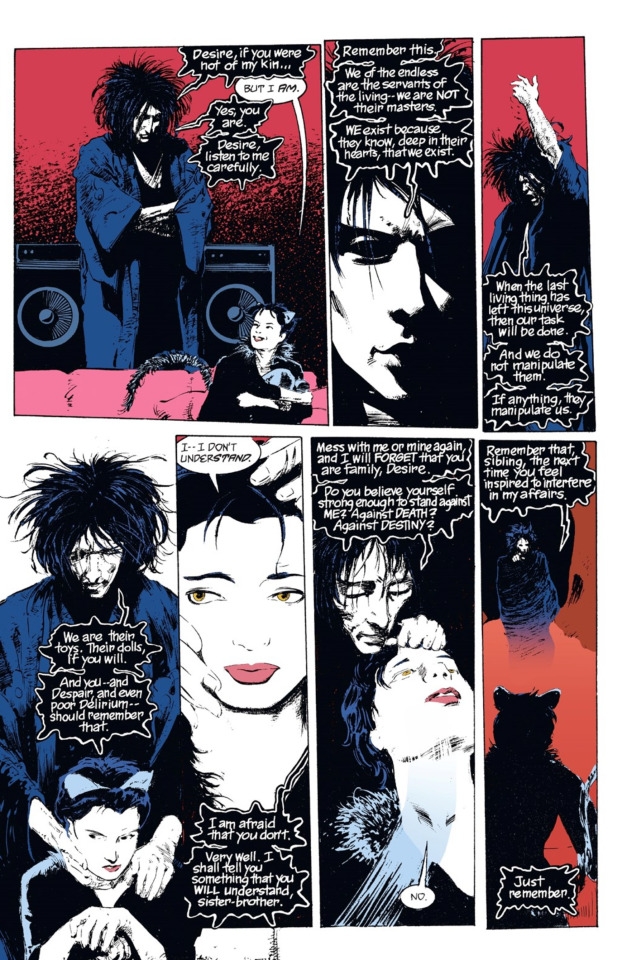

The character Desire directly challenges this definition of the binary described above through their ambiguous and fluid presentation. Toward the end of the same chapter as Unity’s sacrifice, we see an interaction between Dream and Desire where we get a better understanding of Desire’s identity. As one of the Endless, Desire defies categorization within traditional gender binaries, embodying characteristics that transcend fixed notions of male and female.

Desire's depiction as an androgynous being reflects the limitations of the sex/gender binary in capturing the complexity of human identity. Throughout the narrative, Desire is referred to using a variety of pronouns, including "it," "he," and "she," (Gaiman, 439) further blurring the lines between conventional gender categories. This ambiguity challenges the assumption that sex and gender are inherently linked, highlighting the fluidity and multiplicity of gender identities that exist beyond the binary classification. Judith Butler's critique of the sex/gender binary provides a framework for understanding Desire's character, emphasizing the constructed nature of gender identity and the limitations of binary thinking. By embodying traits that defy traditional gender norms, Desire disrupts the idea of a fixed alignment between biological sex and gender expression, encouraging readers to question and challenge existing notions of gender.

Furthermore, Desire's ability to impregnate Unity (as Dream finds out on page 437) further destabilizes traditional conceptions of gender and reproduction. This act challenges the notion that biological sex determines one's capacity for reproduction, highlighting the complexity of human sexuality and the ways in which it transcends binary categorizations.

(1) Judith Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999) 338-339.

(2) Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: oxford University Press, 2009), 713.

(3) Mulvey, "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," 719.

(4) Butler, "Gender is Burning," 338.

(5) bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 318.

0 notes

Text

Class #19: Ecological Feminism and the Importance of a Name

Kelsey Coppinger

November 5, 2018

Class #19: Ecological Feminism and the Importance of a Name

Karen Warren starts her essay The Power and Promise of Ecological Feminism with the definition of ecological feminism. She states that ecological feminism is the position that there are important connections between the domination of women and the domination of nature. Warren's’ argument is that ecological feminism provides a framework which “takes seriously” the connection between the domination of women and the domination of nature. At the base level feminism is a movement to end all sexist oppression even if different feminists argue about how to get there. Warren then explains that a feminist issue depends on context, and it is when an understanding of an issue leads to an understanding of the oppression of women. Warren jumps to says that environmental degradation and exploitation must be a feminist issue since it affects women’s lives.

Next, the idea of conceptual framework is presented. Warren states a conceptual framework is “a set of basic beliefs, values, attitudes, and assumptions which shape and reflect how one views oneself and one’s world” (pp. 283), and an oppressive conceptual framework is a socially constructed lens which contributes to oppression. For instance a patriarchal society is an oppressive conceptual framework in which the lens leads to the domination of men and the subordination of women. Warren then claims there are three features of oppressive conceptual frameworks. The first is value-hierarchical thinking; the second is value-dualism; the third is logic of domination (pp. 283). Warren claims that the first two wouldn’t make a conceptual framework oppressive. They are simply descriptions. The value hierarchical thinking, for example one that ranks height, only becomes oppressive when we say the tallest person gets priority. For value-dualism we can say there is a difference between men and women, but it only become oppressive when we say one is superior to another. Thus, claims Warren, it is the logic of domination that justifies the subordination of one over another. She calls this the “explanatorily basic” (283).

Warren claims that there are three reasons why a logic of domination as the explanatorily basic is important for ecofeminism. The first claim is that without it there would be no way of claiming the moral superiority of humans over say, rocks. The second claim is that in many ecofeminists in the West view the idea of women being equated to nature as oppressive. It follows that women when identified with nature are seen in the realm of the physical while men are identified with human in the realm of the mental. Thus men are superior. Warren points out that logically the patriarchal framework and the second claim ought to be rejected. She moves on to explain how different ecofeminists argues about the second claim, but states that despite these differences they can all agree upon “the way in which the logic of domination had functioned historically within patriarchy to sustain and justify the twin dominations of women and nature” (pp. 284). In other words women and nature are placed together in the logic of domination. They’re seen as passive, uncontrollable, and irrational. What justifies the subordination of women is the same thing that justifies the subordination of nature.

Warren gives an example of deforestation in India and how it disproportionately affects women. In developing countries women are at home so they have a more intimate connection with nature. Warren states that historically nature and women have been devalued while ecofeminism is trying to re-value them. She even shows how our language and use of language tends to relate women to nature for instance the term “mother nature.” Additionally the portrayal of women in mythology shows Goddesses associated with nature. Furthermore Earth is often portrayed like a woman laying there ready to be cultivated or impregnated. Just like women, the Environment is something to be exploited. For ecofeminism the important connection between the domination of women and nature is recognized. Warren explains that since the sexist oppression is connected with the oppression of the natural world then feminism is also against the oppression of nature. Warren further that both of these kinds of oppression are connected with all other forms of oppression. So, Feminism clearly will reject patriarchy and so will ecofeminism since its patriarchy that allowed for the unjust domination of exploitation of nonhuman nature.

Warren’s claim takes issue with the logic of domination. It doesn’t actually address the problem with the identification of women with nature, which many would argue is a major issue. However, I took her claim of ecofeminism as not stating that nature and women are the same, but rather historically their identified as the same. To make this more clear, Warren should specify if she’s stating a historical truth or an actual truth. Additionally I think the same argument that Warren makes for feminism could be made for anti-racism. Black people are often portrayed with nature. For example the recent cartoon of Serena Williams after the US open portrayed her with racist features that reflected the Jim Crow caricatures. These caricatures show black people as uncivilized portraying them with “monkey like” features. Another recent example is the comment that was made by Roseanne Barr about Valerie Jarrett calling her the offspring of “Muslim brotherhood and Planet of the Apes.” Additionally African Americans were forced to pick cotton, or grow wheat during slavery. They were subordinated into being closer to nature than the slave-owners. So, why call this ecofeminism? Why not call is “eco-anti-rasism?” Or why not just call it social-ecology? The name suggests the importance, and arguable this name is claiming feminism as more important than anti-racism.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/09/12/asia-pacific/social-issues-asia-pacific/melbournes-herald-sun-reprints-racist-cartoon-serena-williams/

Word count:909

Warren, Karen J. « The Power and Promise of Ecological Feminism », Multitudes, vol. no 36, no. 1, 2009, pp. 170-176.

0 notes