#Kazuya Tsurumaki & Hiroyuki Imaishi

Text

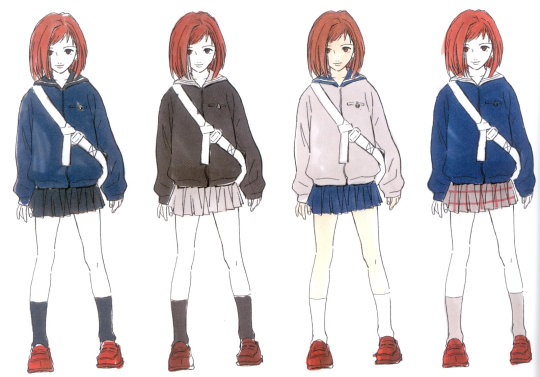

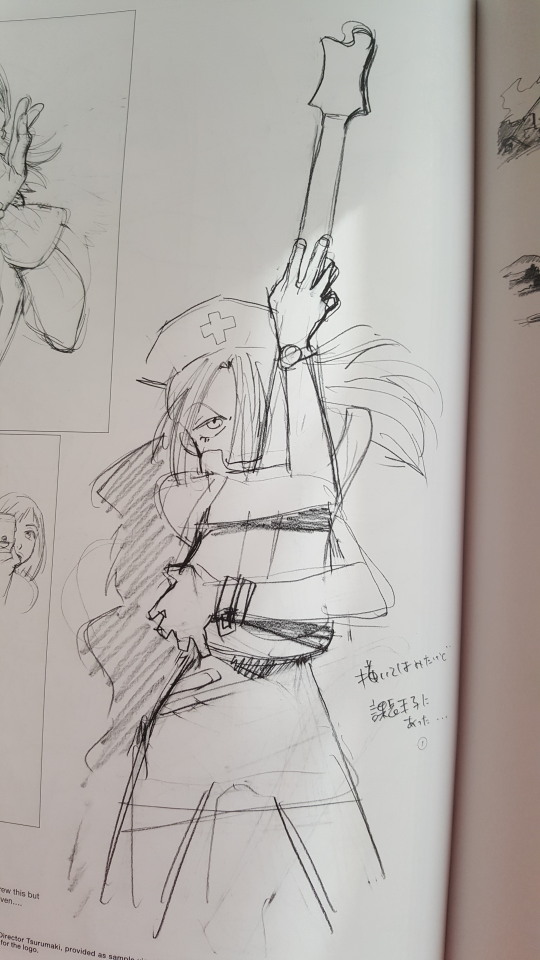

Smoker girl

#official art#Kazuya Tsurumaki & Hiroyuki Imaishi#Kazuya Tsurumaki & Hiroyuki Imaishi#Mamimi#Stephanie Sheh

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

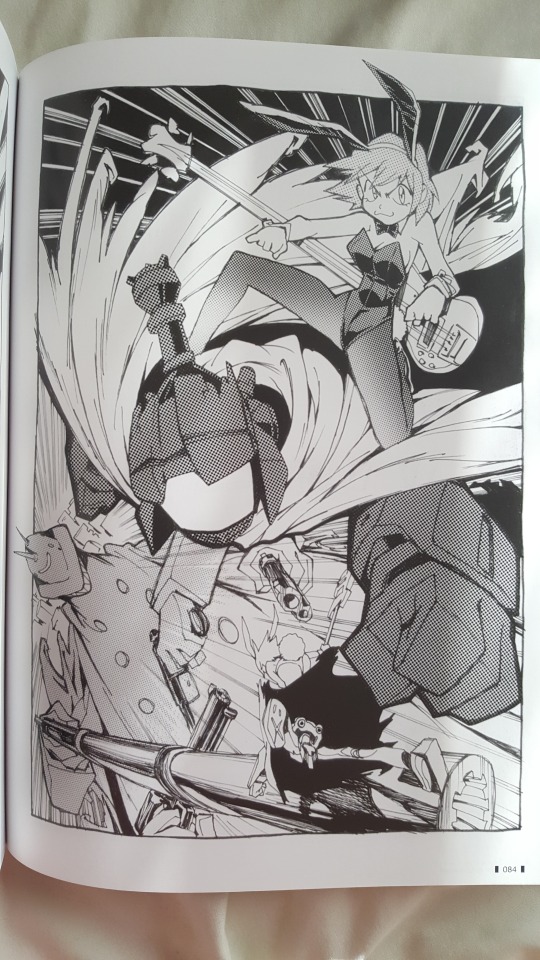

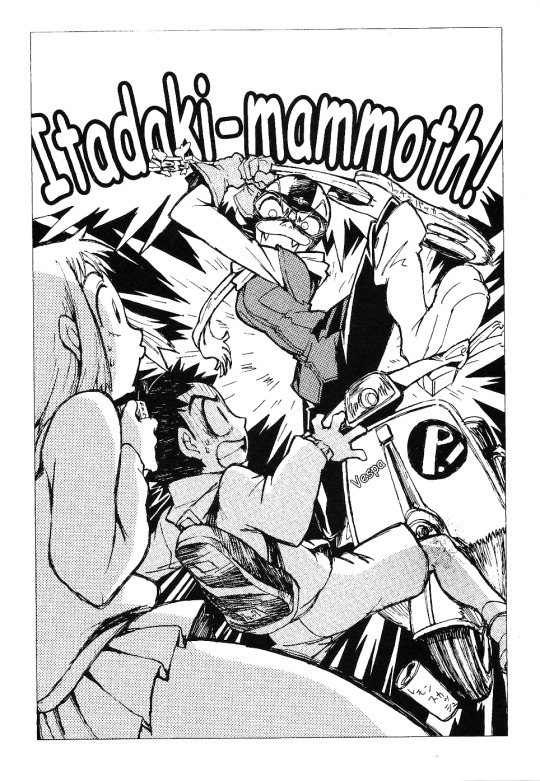

Illustrations from Volume 3 of the FLCL light novels by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

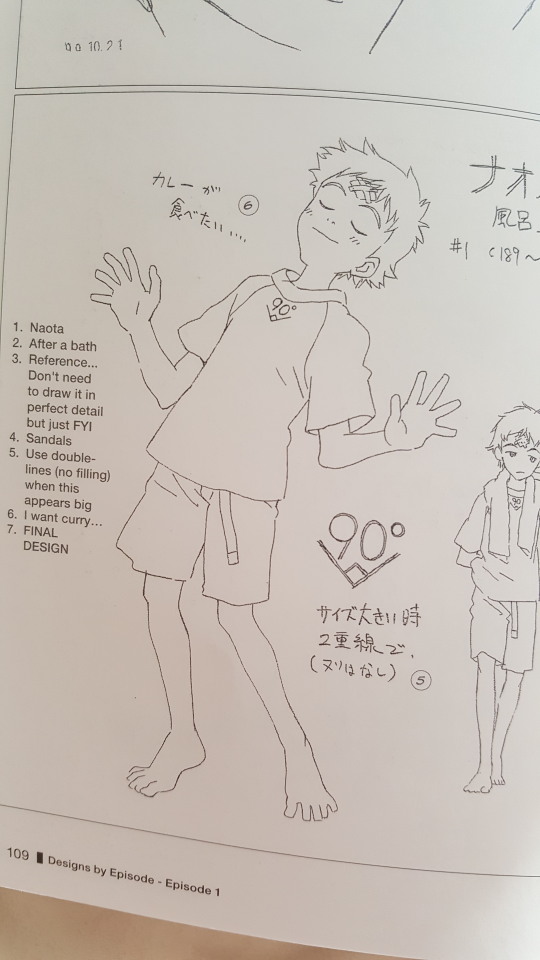

Some of my favorite artworks from the flcl archives I havent seen anywhere else before

#flcl#the flcl archives#gainax#haruhara haruko#naota nandaba#samejima mamimi#canti#amarao#kitsurubami#eri ninamori#kamon nandaba#tadashi hiramatsu#hiroyuki imaishi#yoshiyuki sadamoto#kazuya tsurumaki#artbook#fooly cooly#furi kuri#フリクリ

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 54 - FLCL

Hey friends! Perhaps surprisingly with the amount of Gainax we’ve covered here, I’ve never actually watched FLCL! But tonight? We’re going to fix that...

“huh, what’s this one, Eff Ell Cee Ell?” “baka! it’s pronounced Fooly Cooly!” “uh, sure, ok? do i know you?” - more or less how i imagine anime conventions went in the mid 2000s

FLCL is a six-episode OVA from THE YEAR 2000, a high point in the Gainax’s arc between their other most famous works like Eva and Gurren Lagann. (Previously on Animation Night: Rebuild of Eva, early Gainax, Hiroyuki Imaishi, Gurren Lagann). Hot on the tail of the incredible but harrowing film End of Evangelion, it was the studio’s chance to pour their built up energy into something much lighter, a portrayal of a different side of adolescence in all its confusion that gleefully blends metaphor and sci-fi, all set to the music of indie band The Pillows.

For the director of this one, we need to introduce another member of the Gainax cast. FLCL was the creation - and directorial debut! - of Anno’s protégé Kazuya Tsurumaki (whose The Dragon Dentist opened the Animator Expo making him one of the first people we ever watched on Animation Night), and what a statement it is, consciously an attempt to experiment with the ‘rules’ of TV animation from soundtrack to pacing. Tsurumaki would go on to direct Diebuster, a stylistically distinct (but cool as hell) sequel to Gunbuster about a girl who is the mecha; then, in the late 2000s, he’d follow Anno to Studio Khara to work on the Eva Rebuilds.

But he’s certainly not the only person to make FLCL: it is also an absolute sakuga feast, giving its key animators a lot of space to express their particular styles. By this point, renowned animators like Yoh Yoshinari and Tetsuya Nishio had been pushing themselves to create some of Eva’s most brutal scenes, and were ready to cut loose and drop some of the most insanely cool sequences of their careers. It was a milestone for Hiroyuki Imaishi too, the first time he directed an episode (episode 5) as well as a chance to bring some of that relentlessly chaotic, visual-gag-heavy directing style to his key animation... All that energy and charm extends very much to the character acting oriented scenes as well, with some really delightfully exaggerated poses and emotions giving it a particular charm, but also the ability to convey subtler and quieter scenes like the many atmospheric canalside shots.

It also... struggling to find the right words for this, but looking at the animation and character designs really seems like a fascinating transitional point from the kinds of slightly angular, character designs and animation styles of the 80s-90s OVA era, like we saw last week in Down Load, into the particular kinds of stylisation and exaggeration that would later become the Imaishi/Trigger signature...

So what’s it about? In terms of literal plot details: 12-year-old kid Naoto Nandaba gets whacked on the head by a vespa-riding girl with a bass guitar named Haruko, which like most head injuries, results in robots periodically emerging from his forehead. Fortunately, Haruko - claiming to be a space cop - is able to subvert one of the robots and give Naoko a way to defend himself, but her presence draws the attention of legions of suited goons from the

Yet even before this happens, things seem a little strange: the town in which he lives is dominated by a looming corporate building that looks exactly like a clothing iron. Which feels like a way of saying, don’t try to interpret this too literally!

Over the course of those six episodes, it sounds like things go some pretty wild places! One sequence both @lyravelocity and @mogsk were keen to mention was the episode designed to take after a manga, with the motion edited into black and white panel borders and physical sound effects. Apparently this was accomplished by drawing an enormous manga page as a background, and moving the multiplane camera over it along with the cels, in one of the most technically complex anime shots ever filmed at the time. I can’t wait to see it!

(I also can’t deny FLCL has some troubling elements, or at least ones worth flagging up in advance. F’r example, there’s apparently one episode where the main character’s dad chases him around in a nazi uniform repeatedly seig heiling, which I believe is in context a crass way to signify his authoritarian attitude with a visual gag. I haven’t heard about anything in it that I would consider outright evil; a spirit of irreverence and experimentation is sometimes going to go some misguided places as much as it succeeds in creating something brilliant and new, but you know, don’t let your psychic armour down entirely, this is a Gainax show!)

Unfortunately for such a renowned work of animation, the existing prints of FLCL are not fantastic. We’re left with the choice of either the Japanese DVD release in interlaced NTSC which is of course low resolution and poorly suited to computer playback, or a blu-ray release which applies a detail-removing, over-filtered digital upscale, and also messes with the crop and colours. It’s kind of a case of pick your poison, and some nyaa uploaders prefer the DVD, while others use the bluray. I’m going to test out both on my system and make a decision on the night; of course, given I’m streaming to you over Twitch, it’s kind of moot on your end ><

There are, at least, extensive production materials available: storyboards, commentary tracks, and interviews with the creators which I would like to show if time permits! (Which it probably will, because the total runtime of the OVA is only about 3 hours.)

And then, the sequels. FLCL received a pair of sequel series airing in 2018 titled FLCL Alternative and FLCL Progressive. The circumstances of their creation are a little weird: at first, Gainax (now a shell of a company, with all its big names departing to Khara and Trigger) was set to sell the rights to Studio Khara, with whom it was also fighting a lawsuit over refusal to pay Evangelion royalties; according to Anno, Gainax jacked up the price at the last minute and the deal fell through.

Instead, the main animation work on the sequels was handled by Production I.G. (who had been part of the original show’s production committee) with support from several young studios like Signal.MD, Revoroot and NUT. Several of the staff returned, including the original character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, and while Tsurumaki apparently supervised (but did not direct) the project... the general feeling I’ve gotten towards these series is lukewarm at best, certainly not as well regarded as the original. Is that fair? I can’t say, but I’m not gonna consider screening them til I’ve watched them myself.

Animation Night 54: FLCL will begin at 7pm UK time at twitch.tv/canmom - and, gosh, I’m incredibly excited to see this at last, it sounds like such a fantastic time. Hope to see you there :)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

serval-chan replied to your post “Can you believe there are actually people out there who don’t like...”

Hiya. Give me some recs so I can actually enjoy the genre for once.

Sure!

Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann is my favorite anime of all time. The most over the top and inspiring anime ever made with the combo of Hiroyuki Imaishi’s stellar directing and Kazuki Nakashima’s excellent writing.

Gunbuster was Hideaki Anno’s directorial debut. It’s a 6 episode OVA and the first half is admittedly a little slow but the second half is fantastic, with awesome action, cool time dilation scifi shit, and one of the best endings of any anime I’ve ever seen.

Diebuster is a sequel to Gunbuster directed by Kazuya Tsurumaki, director of FLCL. It’s pretty different from Gunbuster but also great, with some fantastic animation and action.

Giant Robo the Animation: the Day the Earth Stood Still is a 90s ova adapting a manga from the 60s. I’m always a sucker for anime that uses retro art styles with modern animation quality and this is the best example of that out there. It’s absolutely gorgeous. The source material is also from before mechas were piloted and instead the titular Giant Robo is controlled by a boy with a watch.

Star driver has fantastic mecha animation and pretty much has a gorgeous action scene every episode. It also has the most fabulous mecha pilot of all time, the galactic pretty boy!

If you didn’t watch it last season, SSSS.Gridman was really good. It’s a love letter to old tokusatsu and mecha shows and that really comes through in the animation, and what really makes the show shine is it’s villian who is really interesting and has so much personality, she’s so much fun to watch. It also has a lot of good heavy yuri subtext.

I could recommend more but I don’t want to make a big list so I’ll leave it at that. I hope this helps you learn to love mechas.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fly Me to the Moon: How Hideaki Anno Changed the Anime Industry Forever

There is anime before Neon Genesis Evangelion and there is anime that came after. Hideaki Anno's opus is only one thread in his vast tapestry of accomplishments and contributions to the anime industry, ranging from his collaboration with other creators, the animation studios born in his wake, and the immense influence he has had on the writers, directors, and animators behind virtually all receent anime. Today marks Hideaki Anno's 58th birthday, so it only feels fitting to take a look at the beginnings of this creative mastermind's career, and how his talent and passion have left a mark on the world of anime forever.

Beginning his career working as an animator on projects such as The Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Anno’s talent and passion wasn’t truly recognized until his work on the 1984 Hayao Miyazaki film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The production studio had been running short on animators, and Anno was one of many who answered a help wanted ad in Animage (a well-known anime magazine). Miyazaki was so impressed with Anno’s drawings that he hired him to draw one of Nausicaä’s most challenging (and arguably the best) scene: the God Warrior's attack sequence. Since Nausicaä's release over 30 years ago in 1984, the God Warrior's attack has become animation legend.

At the end of 1984, Anno - along with fellow university students and collaborators on earlier projects such as Daicon IV - founded the animation studio Gainax. Anno’s first project at Gainax was working on the feature film Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise, which, while not a commercial success, is regarded as a cult classic. Gainax eventually went on to be a well-respected studio with hundreds of thousands of fans across the world, due in part to such classics as Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, His and Her Circumstances, and Gurren Lagann, just to name a few.

Most notable of all Anno and Gainax creations is the 1995/1996 apocalyptic mecha anime Neon Genesis Evangelion. To this day, Evangelion has risen to a level of ubiquity most creators only dream of. Its place in Japanese culture could justifiably be compared to Star Wars in the West: even those who haven’t seen it were aware of it through endless advertising tie-ins, seeing it on various bits of merch in stores, or simply as one of many ubiquitous pop culture references. If you haven’t seen Star Wars, there’s still a good chance you know what a Jedi and a lightsaber is, right? It’s like that, but Unit 01 and Angels instead.

Since its release, Evangelion has spawned various manga adaptations, video games, a film that re-tells the controversial original ending, and a four-piece movie reimagining that diverts greatly from the original storyline.

Among many achievements, Evangelion is credited with reinventing (and rejuvinating interest in) the mecha genre, influencing Japanese animation at a time when the industry was in a slump, and impacting the overall global spread of anime. The mature, nuanced way the series handled themes of depression, nihilism, and existential horror ushered in a new era for anime. The years following Evangelion's release saw an increase in dark, psychological dramas aimed at more mature audiences. Movies like Perfect Blue, and TV anime such as Serial Experiments Lain walked the path paved by Anno's groundbreaking series. The series also left a huge impact on the way anime was televised! Shinya anime is a term that refers to anime series scheduled at late night or early morning hours created for an adult audience. Scheduling blocks for these series was hugely expanded after the massive success of Evangelion, setting the stage for anime's TV distribution to this day.

Beyond critical and scholarly acclaim, many anime creators themselves are proud to credit Evangelion as a creative influence. Most notably is Your Name auteur Makoto Shinkai, who believes anime owes a cinematographic debt to Evangelion, also believes Evangelion taught him that anime wasn’t just about lavishly animated action sequences, but could simply be about the words - whether they were spoken or not.

Though Anno’s mark on the industry is largely related to Evangelion, he has also left a lasting influence in a different way -- the creation of production studios. Anno founded his current studio, Khara, in 2006, and officially resigned from Gainax in 2007. While Khara’s flagship title is (and likely will always be) the Evangelion Rebuilds, the studio also collaborated with Dwango to create the critically revered Japan Animator Expo series of shorts. Khara also cooperated with other studios to co-animate, provide in-between animation, and offer up various odd jobs for productions such as Ponyo, From up on Poppy Hill, The Wind Rises (of which Anno is a lead voice role), Star Driver, Persona 4: The Animation, Flowers of Evil...the list goes on.

If Anno's cultural footprint is intwined with that of Gainax, his legacy expands to some of the most important studios of modern anime. Before Khara’s inception, the animation studio Gonzo was formed in late 1992 by former Gainax staffers. Perhaps most famous of all Gainax offshoots, however, is Studio Trigger. Founded by highly-regarded ex-Gainax employees Hiroyuki Imaishi and Masahiko Ohtsuka, Trigger has blazed a trail in highly stylized, beautifully produced animation. Since its inception, Studio Trigger has produced a number of shorts (Little Witch Academia movies), ONAs (Inferno Cop and Ninja Slayer From Animation) and television series (Kill la Kill, Kiznaiver, Little Witch Academia, and the currently airing Darling in the Franxx).

Beyond studios, Kazuya Tsurumaki -- Anno's protege and Evangelion assistant director -- went on to create one of anime’s most well-known series that follows a coming of age story of a young boy as he struggles through puberty, love, and the robot in his head. That’s right: the disciple of Anno himself went on to create and direct FLCL, a series held so dearly in the hearts of fans worldwide, that it spawned two additional series that air really, really soon (and look really, really good).

While Evangelion fans wait patiently (or not so patiently) for the final Rebuild film’s release, one can only speculate so to what’s over the horizon for Anno. Whether it’s more Evangelion, another entry into the Godzilla franchise, or something new entirely, we can only hope it contains the amount of creative talent, passion, and energy we’ve come to love and expect from him. So here’s to you, Hideaki Anno, for your creativity, your undying influence on anime through the years, and to your 58 years of life. Happy Birthday Anno-sensei!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait : ANNO Hideaki (pt.1)

Writer

Il est difficile aujourd’hui de n’avoir jamais entendu le nom de Hideaki ANNO lorsque l’on s’intéresse au monde de l’animation japonaise. Membre clef et créateur du studio Gainax, on peut notamment lui attribuer la parenté des séries Nadia, le secret de l’eau bleue et Neon Genesis Evangelion, deux importants succès en matière d’animation dans les années 90. Si l’on ajoute à son parcours la série d’OAV Gunbuster ainsi que sa présence sur les réputés Daicon III & Daicon IV, Hideaki ANNO s’impose incontestablement comme l’un des plus grands noms du monde de l’animation.

Cependant, si ses réalisations animées sont parmi les plus réputées, ses longs métrages en prise de vue réelle restent aujourd’hui largement méconnus. C’est pourtant avec deux adaptations de roman et une de manga entre 1998 et 2004 que Hideaki ANNO a poussé jusqu’à ses plus profonds retranchements le propos sous-jacent qu’il avait développé dans Neon Genesis Evangelion puis dans The End of Evangelion. C’est en créant ainsi un leitmotiv à destination à la communauté otaku qui allait nourrir une part importante de sa filmographie que Hideaki ANNO s’est imposé comme l’un des auteurs importants du cinéma japonais des années 90-2000.

D’Ube à un Tokyo animé

Né en 1960 à Ube dans la préfecture de Yamaguchi au Japon, Hideaki ANNO se passionne rapidement pour le cinéma, qu’il soit en prise de vue réelle ou en animation. Il entame sa carrière de réalisateur à l’âge de 17 ans avec un premier court métrage intitulé Nakamu-Rider qu’il filme en 8mm. En 1980, il entre à la section cinéma de l’Université d’art d’Osaka où il y réalise Ultraman avec Hiroyuki YAMAGA, un court métrage parodique de la série homonyme où les deux réalisateurs se partagent le rôle principal. Un an plus tard, les deux compères renouvellent l’expérience à l’occasion d’un concours dans leur école où ils se classeront à la cinquième place avec le court métrage Ultraman Deluxe.

Cependant, il faut attendre 1984 pour que le feu des projecteurs se tourne réellement vers Hideaki ANNO lorsque, à la suite d’une annonce dans le magazine Animage, il est embauché comme animateur clef sur Nausicäa de la vallée du vent de Hayao MIYAZAKI pour animer la séquence du robot géant. La même année il crée avec plusieurs de ses compères le studio Gainax pour produire le film Les Ailes d’Honneamise de son camarade Hiroyuki YAMAGA. Au cours de son histoire, le studio s’est affirmé comme un élément essentiel de l’animation japonaise avec plusieurs grands noms en son sein comme Yoshiyuki SADAMOTO, Kazuya TSURUMAKI ou encore Hiroyuki IMAISHI.

Si le film de Hiroyuki YAMAGA est un échec commercial, la Gainax ne disparaît pas pour autant et sort l’année suivante la première création animée que l’on peut attribuer à Hideaki ANNO, Gunbuster. Non content d’être un premier succès pour la Gainax et d’être annonciatrice en de nombreux points de Neon Genesis Evangelion, la série de six OAV entre dans l’histoire puisque la postérité lui a attribué la parenté du Gainax Bounce, cette attention particulière des animateurs sur l’animation des seins des personnages féminins.

Moins marquée par ce qui caractérisera le cinéma de Hideaki ANNO, la série Nadia, le secret de l’eau bleue sort en 1990 et adopte un ton plus léger que Gunbuster. Face au franc succès que la série constitue, les producteurs décident de commander neuf épisodes supplémentaires dont Hideaki ANNO confiera la réalisation à Shinji HIGUCHI. C’est durant cette même période qu’il sombre dans une profonde dépression causée par un trouble de la personnalité borderline (ndlr. trouble présent chez la communauté otaku qui est caractérisé par une impulsivité majeure et une instabilité des émotions, des relations interpersonnelles et de l’image de soi). Hideaki ANNO fait alors de multiples tentatives de suicide et se retire peu à peu du monde extérieur.

C’est durant cette dépression, qui durera près de quatre ans, que Hideaki ANNO commence à construire le leitmotiv qui allait porter sa filmographie de 1995 à 2004 et qui allait afficher ses premiers traits à la sortie de Neon Genesis Evangelion, en 1995. En plus d’être l’une des séries d’animation les plus importantes de l’histoire ayant connu un succès colossal à sa sortie et d’être l’une des principales références en matière de mecha, la série marque profondément les esprits en abordant des sujets qui n’avaient alors quasiment jamais été traités auparavant.

Tout en abordant de nombreuses problématiques philosophiques et existentielles, Neon Genesis Evangelion se place dans un premier temps comme un véritable pain béni pour la communauté otaku en proposant une série basée sur une lutte entre robots géants et monstres divers accompagnée de personnages sur-sexualisés, ce qui en somme réunissait la majeure partie de ce qui plaisait au milieu des années 1990. Cependant, au fur et à mesure des épisodes, la série a connu un tournant progressif menant l’intégralité des personnages vers de profondes dépressions. Lors d’une des rares interviews que Hideaki ANNO a accordé au cours de sa carrière, il expliqua que les marasmes de l’âme qu’il inflige à ses personnages étaient issus des réflexions qu’il avait eu durant sa dépression et que ses trois personnages principaux – Shinji, Rei et Asuka – correspondaient à trois facettes de sa personnalité.

Malgré l’important succès que connaît la série lors de sa sortie, une polémique accompagne la diffusion des deux derniers épisodes. Occultant ouvertement la fin de l’histoire et quasiment expérimentaux, ces épisodes se passent intégralement dans la tête d’un personnage alors en pleine introspection. C’est avec ces épisodes à la mise en scène radicale que Hideaki ANNO trouve alors un médium qui lui permet d’adresser une message directement à la communauté otaku. Lui même issu de cette dernière, il tente d’expliquer la manière dont il est sorti de sa propre dépression en invitant ses spectateurs, de manière plus ou moins virulente, à changer leur mode de vie en se confrontant à la réalité et à arrêter de se livrer à une telle forme d’auto-destruction.

À la suite de ces deux épisodes majoritairement mal reçus par les fans, Hideaki ANNO et ses collaborateurs se sont vus adresser de nombreuses menaces de mort les invitant à changer la fin de la série. Pour répondre à cette demande, et comme le veut un certain écueil obligatoire des séries animées à succès, des films ont été annoncés pour apporter la fin initiale de Neon Genesis Evangelion. Dès lors, en mars 1997 sort Death & Rebirth, un re-cut de la série accompagné d’une petite quinzaine de minutes de contenu original. Bien qu’il soit dû à une contrainte budgétaire et à des retards accumulés dans la réalisation, ce manque de contenu inédit a été perçu par certains comme une seconde provocation de la part de Hideaki ANNO à l’encontre de ses fans. Ainsi, avec la sortie de The End of Evangelion en juillet 1997, on pouvait craindre de retrouver un Hideaki ANNO ayant fait le choix d’une narration plus académique et plaisante pour la communauté otaku afin d’offrir cette fameuse fin à Evangelion. Pour autant, le réalisateur renouvelle le message qu’il avait inculqué lors des deux derniers épisodes de Neon Genesis Evangelion de manière encore plus explicite, accusatrice et viscérale au cours d’une représentation expérimentale d’une demi-heure de l’apocalypse venant conclure le film.

Finalement, la conclusion est que le projet Evangelion est un échec vis à vis du leitmotiv que souhaitait inclure Hideaki ANNO, puisque la série créa plus d’otakus qu’elle n’en aida et a nourri de nombreux troubles de la personnalité borderline. C’est à la suite de cela que le réalisateur est retourné à sa première passion, le film en prise de vue réelle, pour entamer la période la plus riche de sa filmographie où il remettra en question l’essence même de son cinéma tout en continuant d’explorer l’esthétique développée dans la séquence en prise de vue réelle de The End of Evangelion et de sa scène alternative.

Love & Pop : Tokyo et sa jeunesse décadente

Après un différent artistique sur l’adaptation du manga Entre elle et lui, Hideaki ANNO quitte la Gainax et sombre dans une nouvelle dépression. À la suite de celle-ci, il enfile à nouveau la casquette de réalisateur en 1998 pour son premier long métrage en prise de vue réelle Love & Pop, une adaptation de Topaz II de Ryū MURAKAMI. Si le romancier avait déjà auparavant adapté plusieurs de ses romans, comme Bleu presque transparent en 1979 ou Tokyo Decadence en 1992, Hideaki ANNO devient néanmoins le premier réalisateur extérieur à transposer sur grand écran la vision sombre et pessimiste que Ryū MURAKAMI porte sur une société japonaise à la dérive et sur une nouvelle jeunesse en manque de repères.

Extrêmement contemporain de son époque, Love & Pop traite, au travers du portrait de quatre lycéennes, le phénomène de société que représente l’enjo kōsai, ou compensated dating, une pratique japonaise où de jeunes adolescentes – principalement des lycéennes – sont payées par des hommes plus âgées pour les accompagner dans divers endroits comme au restaurant ou au karaoké. Véritable source d’argent facile pour subvenir aux spasmes consuméristes d’une jeunesse aux besoins immédiats dans une société ravagée par l’explosion de la bulle spéculative, l’enjo kōsai constitue aussi parfois la dernière marche à franchir avant la prostitution.

Outre son sujet quasi tabou, l’une des principales performances de Love & Pop se situe dans son esthétique qui vient embrasser à la perfection la fugacité de cette jeunesse sonique que Ryū MURAKAMI décrivait dans son roman. Au travers d’un montage cut allant transcender les séquences les plus rythmées de Neon Genesis Evangelion, Hideaki ANNO propose une esthétique unique basée sur un style expérimental particulièrement saccadé et déroutant – les champs-contrechamps pouvant durer moins d’une seconde – qui nécessite un effort certain au spectateur pour s’acclimater au film. De même il met en place un véritable terrain de jeu en changeant régulièrement le format de l’image dans une même scène, en ayant recours à de multiples distorsions ou en exploitant au maximum la taille de petites caméras numériques afin de proposer de nombreux plans peu usuels et les plus originaux panchiras de l’histoire du cinéma japonais. Cette esthétique atteint par ailleurs son climax en prenant le spectateur à contre-pied lors de son générique en plan séquence de 6 minutes filmé en 35mm sur une reprise de Ano Subarashī Ai Wo Mō Ichido de Osamu KITAYAMA et Kazuhiko KATŌ par Asumi MIWA.

Mais si Love & Pop est indissociable de la verve de Ryū MURAKAMI, le film reste néanmoins très personnel à Hideaki ANNO et au message quasi-similaire à celui que le réalisateur avait inculqué dans Neon Genesis Evangelion et The End of Evangelion. Interrogeant plus spécifiquement sur les rapports entre individus, sur la manière dont la jeunesse trouve un semblant de bonheur dans la consommation de biens et invitant la jeunesse à vivre décemment par respect pour les individus qui tiennent à eux, le film met indirectement en exergue les points communs existant entre ces lycéennes et la communauté otaku. Chacun d’eux cherchant des ersatz de réalité dans des mondes fictifs tels que l’animation, les mangas, la consommation, etc.. Tels deux fruits différents et pourtant si similaires, les otakus et les adolescentes de Love & Pop sont tous deux issus d’un Japon que Hideaki ANNO décrit comme un pays de grands enfants qui, en l’absence de repère adulte fiable, n’ont jamais pu grandir et ne peuvent affronter la réalité qu’au travers d’un monde fait de fiction.

En élargissant sa cible à l’ensemble d’une jeunesse qui voyait ses perspectives d’avenir se ternir, Hideaki ANNO dresse une simple observation d’un phénomène de société qu’il accompagne de sa volonté d’aider autrui à ne pas s’autodétruire et de la noirceur du roman de Ryū MURAKAMI. Ainsi certains verront dans Love & Pop une jeune Hiromi prendre conscience de ses pulsions et décidant de changer son mode de vie alors que d’autres, plus défaitistes, y verront une jeune fille qui, malgré son épiphanie, continuera perpétuellement sa fuite de la réalité. Dès lors, peu importe la perception que l’on en a, Love & Pop se place comme la caractérisation d’un Hideaki ANNO représentant un ensemble de génération souhaitant sortir de la spirale d’un monde sans repères au travers d’un énième appel au secours.

Malgré le succès qu’ont été Nadia, le secret de l’eau bleue et Neon Genesis Evangelion et malgré la présence de grands noms du cinéma indépendant tel que Tadanobu ASANO ou Mitsuru FUKIKOSHI, Love & Pop n’a pas bénéficié d’un public important et n’a donc pas eu l’occasion de transmettre pleinement son message auprès des individus à qui il était destiné. Pour autant, le film est devenu malgré tout avec le temps un film symbolique de l’art underground japonais à l’instar du clip de Shinsei Kamattechan pour leur morceau Hikari No Kotoba et de la reprise de Ano Subarashī Ai Wo Mō Ichido par Kindan No Tasūketsu qui s’inspirent ouvertement du générique de fin de Love & Pop.

De plus, Love & Pop constitue la marche essentielle que nécessitait Hideaki ANNO pour mûrir la réflexion initiée à la fin de Neon Genesis Evangelion et qui est venu par la suite les deux autres adaptations en prise de vue réelle qui ont suivi. Véritable quête identitaire et volonté d’aider une communauté dont il fait partie intégrante, le tournant qu’a pris la carrière de Hideaki ANNO en 1995 se concrétisera en 2000 avec la sortie de Shiki-Jitsu en devenant un profond retour sur soi puis évoluera en une allégorie de candide et survitaminée de celui qu’il a été depuis 10 ans avec la sortie de 2004 de Cutie Honey.

Critique publiée dans le webzine Journal du Japon.

0 notes

Text

[ARTBOOK] Die Sterne

Die Sterne (“As Estrelas” em alemão) é um um artbook publicado pela Kadokawa Shoten. Ele contém mais de uma centena de páginas de ilustrações coloridas do designer de personagens original Yoshiyuki Sadamoto e uma longa lista de outros artistas: Takeshi Honda, Shinya Hasegawa, Shunji Suzuki, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Tadashi Hiramatsu, Ichiro Kamei, Kou Youshinari, Você Yoshinari, Hiroyuki Imaishi,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

😼

#Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi#official art#Haruko Haruhara#Vespa#the waspy woman#Humanoid alien#FLCL#Furikuri#foolycooly#Kari Whalgren

16 notes

·

View notes

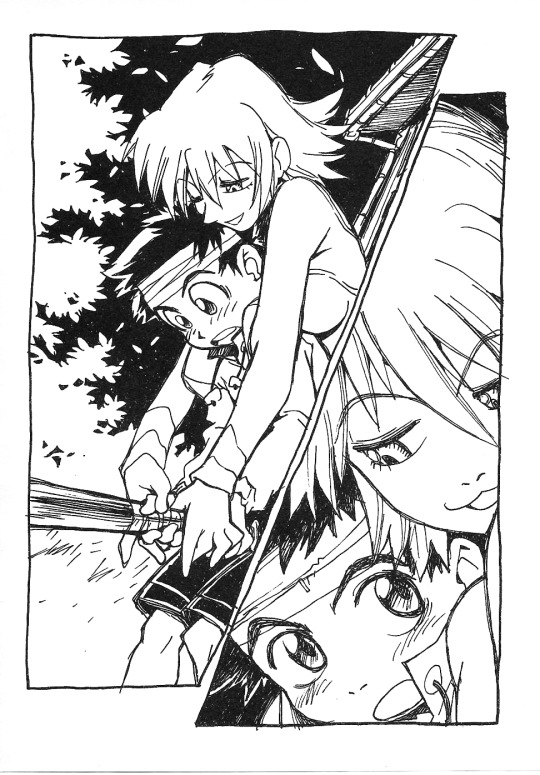

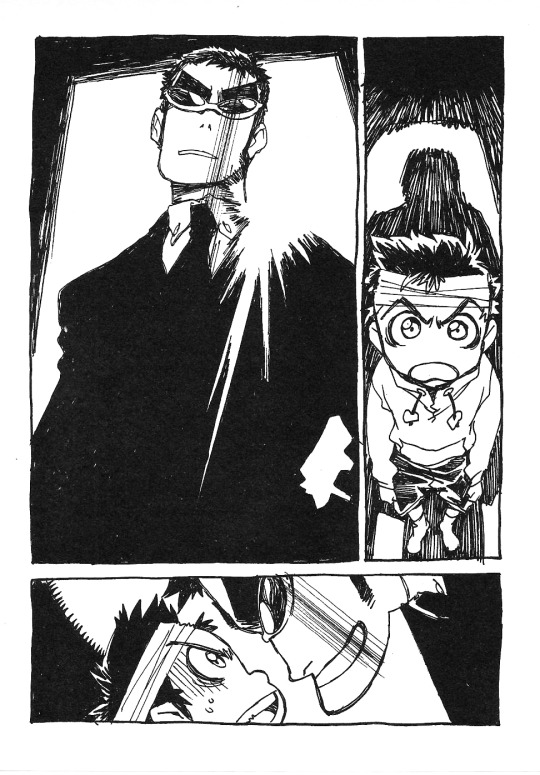

Photo

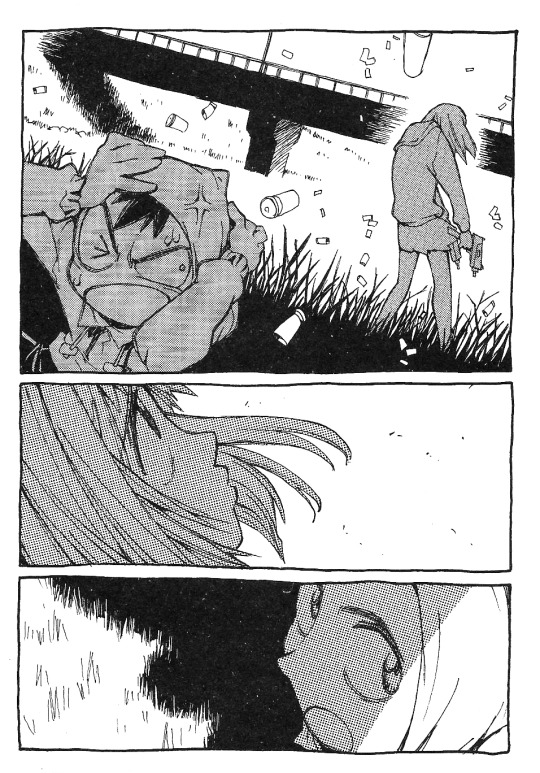

Illustrations from Volume 2 of the FLCL light novels by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi

#FLCL#Ninamori#Naota#Mamimi#Takkun#Kazuya Tsurumaki#Hiroyuki Imaishi#for some reason the book only credits Tsurumaki which really messed me up because some of these are absolutely Imaishi's work#scan#novels

239 notes

·

View notes

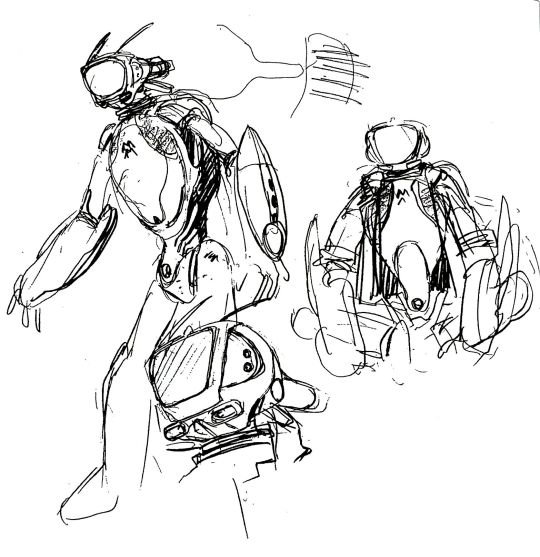

Photo

Early designs for Canti, by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Tadashi Hiramatsu, and Hiroyuki Imaishi.

#FLCL#Canti#Groundworks#Archives#Design Works#scan#hellboy in the fourth image for some reason????#yoshiyuki sadamoto#kazuya tsurumaki#tadashi hiramatsu#hiroyuki imaishi#<-- likely other artists too but those are the ones credited in the caption

409 notes

·

View notes

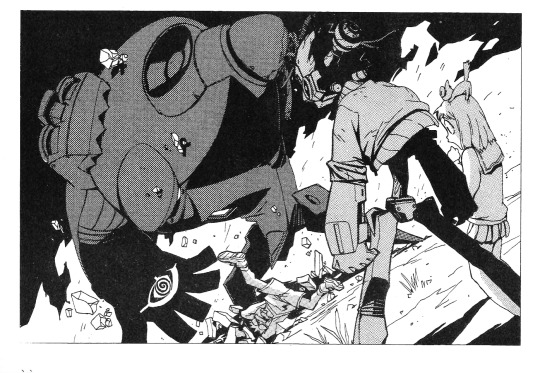

Photo

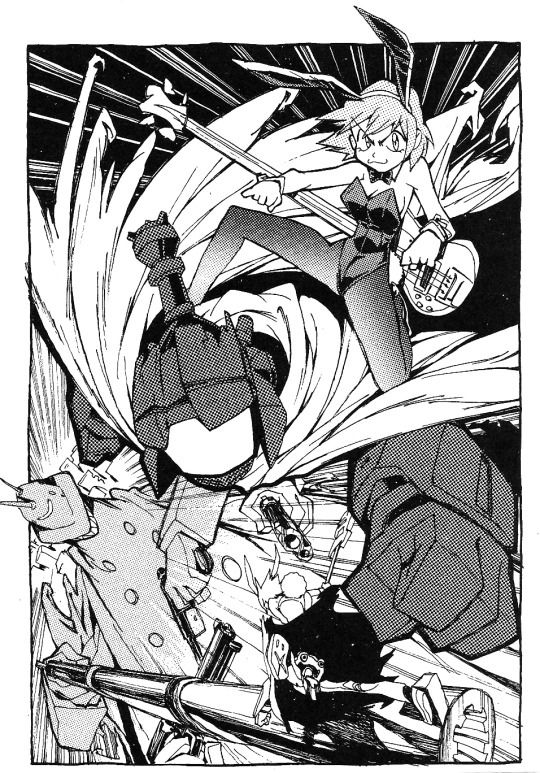

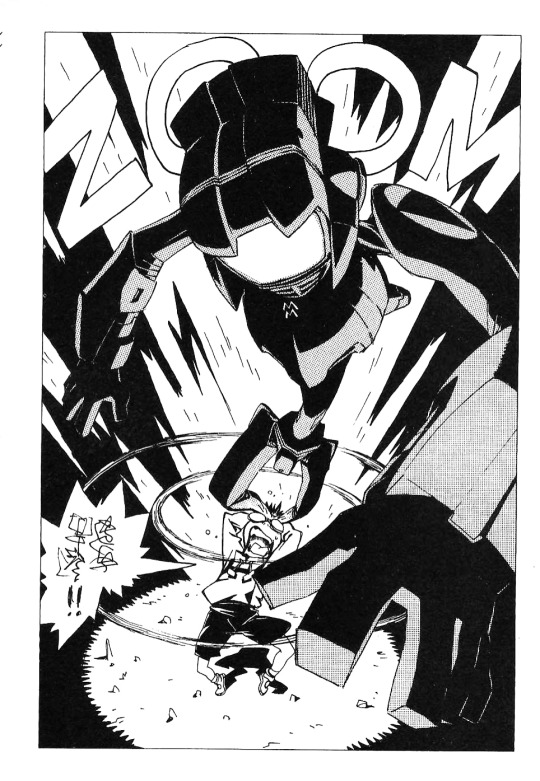

Illustrations from Volume 2 of the FLCL light novels by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi

#FLCL#novels#scan#Naota#Haruko#Amarao#Ninamori#Canti#<- getting completely wrecked in the second image rip#Kazuya Tsurumaki#Hiroyuki Imaishi

187 notes

·

View notes

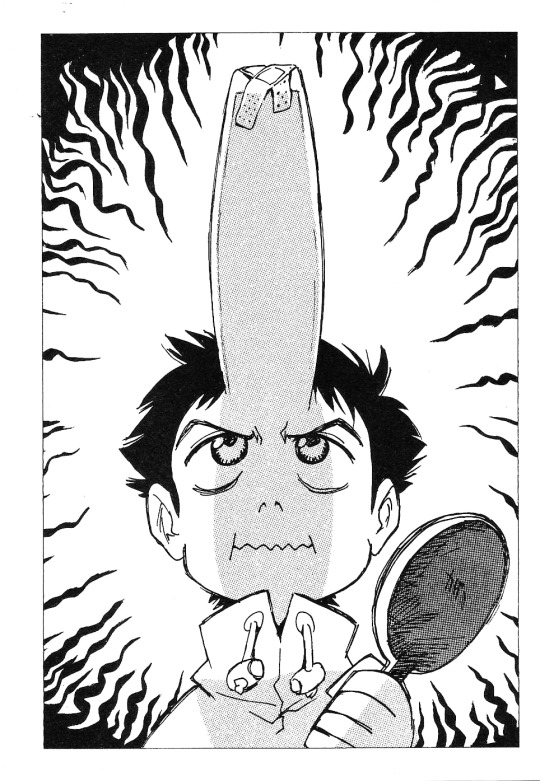

Photo

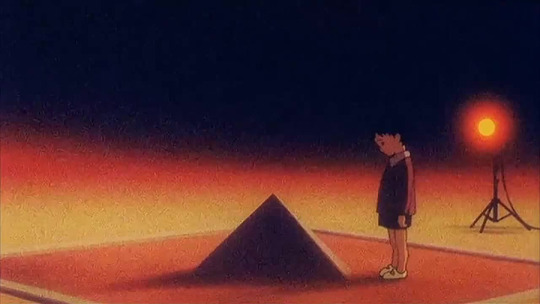

Illustrations from Volume 1 of the FLCL light novels by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi

#FLCL#Canti#Mamimi#Naota#Takkun#novels#hiroyuki imaishi#kazuya tsurumaki#archive.org#scan#part 2 of the first book's illustrations. the last one is rotated because it's easier on the eyes that way

150 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Illustrations from Volume 1 of the FLCL light novels by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi

#FLCL#Mamimi#Naota#Haruko#Canti#well uh. technically that's#Atomsk#but i'm tagging both#Kazuya Tsurumaki#Hiroyuki Imaishi#novels#scan#the text on the top right image is awful to look at. i might go digging for japanese versions of the illustrations to find the kanji ver

137 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Illustrations from Volume 3 of the FLCL light novels by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Hiroyuki Imaishi

332 notes

·

View notes

Photo

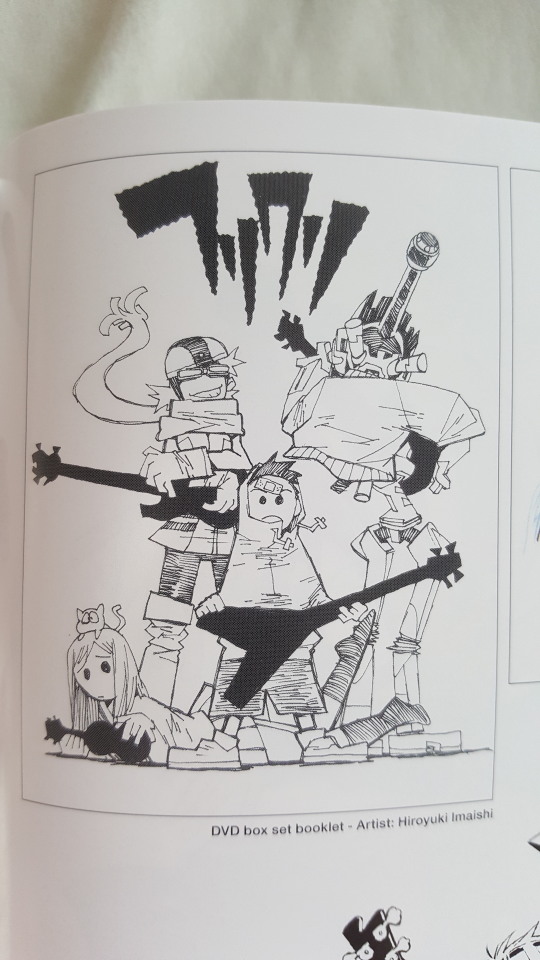

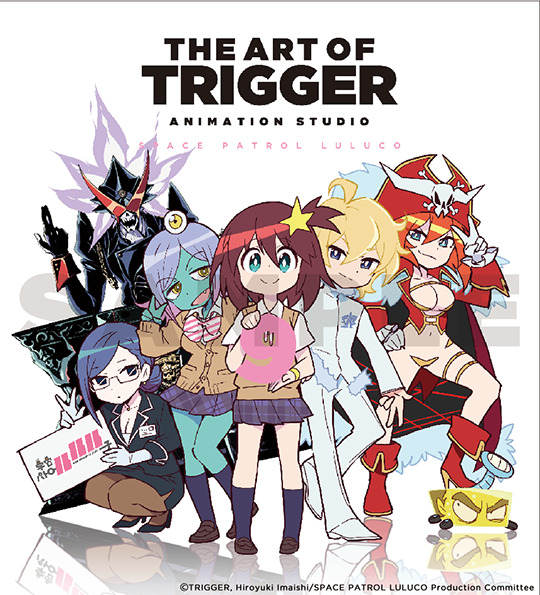

You can order it now: http://trigger-global.ecq.sc/top/trg-os-aot-001.html Includes Imaishi and Tsurumaki illustrations. This is gud.

#luluco#space patrol luluco#hiroyuki imaishi#shigeto koyama#akira amemiya#kazuya tsurumaki#studio trigger

7 notes

·

View notes