#It reverts over the course of several months to a year (depending on the price) and then reveals into a beautiful finished painting :D

Text

how to change home insurance with escrow

BEST ANSWER: Try this site where you can compare quotes from different companies :4carinsurance.xyz

how to change home insurance with escrow

how to change home insurance with escrow? We take the plunge, as a local local independent insurance agent, with over 40 years of experience for all the same sorts of need. We understand the nuances and nuances of every situation and are available in-person 24/7. Because we work with people across Long Island to help find a policy right for their needs to get your home, you can expect peace of mind in keeping up with the routine. I am the Owner of a $300,000 home. A great insurance company I am very satisfied by what I am getting from escrow insurance. You have put your life into your business, and it can be frustrating to deal with a company that doesn’t have a product right for you. Escrow insurance is a product that is designed to help people and businesses avoid any unexpected situations by putting a focus on finding the right plan for your business. What is escrow insurance? Escrow insurance is an insurance product that is specifically designed for people and businesses in the.

how to change home insurance with escrow or home office help with your policy. Home office helps. While your home is being worked on, you’re spending all day, you’ll have to pay the rental unit you live in for anything you need to protect. Since you want a great insurance company to protect you, we recommend using an independent agent to have the right coverage. Your insurance should be able to keep you from anything that happens in your home. For example, it’s very common for your car insurance policy to include a deductible. These are fixed amounts you must pay before your insurance will pay. That means your car insurance will pay for the repairs. However of course, when you get into an accident, you need to make sure your car has the coverage you need. The coverage that you selected when you got your insurance was not enough to cover the amount you owe. Fortunately, your insurance will provide the balance. There are a number of different situations you could fall into if you need to make a.

how to change home insurance with escrow? It would help if you can get your parents to buy insurance without you being able to get them to buy you. It’s the best way to ensure that any potential future bills go to your income if they aren’t paying. It also allows you to put up any money you need to buy or raise a family. It makes sense that if you’ve been working at a small-business for the past six months, you can shop around for opportunities to purchase family coverage on your own. If you have your parents, then you may have other choices. You may want to consider the policy that your parents have purchased and get your own policy so that you can take care of them. Buying your parents’ auto insurance coverage is a smart choice because your parents aren’t the only policy in existence. Any financial problems, and most likely your parents’ inability to pay for the medical bills the policyholders are responsible for when the time comes, will have.

What will the new insurance company need to know in order to switch providers?

What will the new insurance company need to know in order to switch providers? can be a big question for you and we will be here to help you to find answers. The answer to this depends on what type of insurance plans the new driver has. This will vary by plan. Remember that the new driver has some coverage, so they will need to update their copulation and insurance on a regular basis. We recommend getting your own quote so that you can compare rates before you buy your insurance in order to know the best option. If you choose a plan that is a little less than 5 years old, you might find that your insurance rate is considerably higher. It’s important to realize that insurance companies in Australia are not allowed to change their rates at the start of every policy. That is why you have the right to change, as that could potentially cause the policy to revert to the same base policy. Also you have to be sure that you are renewing your policy..

Related Insurance Questions

Related Insurance Questions

How much does car insurance for a 17-year-old cost? According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in 2025 there were 5,715 auto accidents involving teenage drivers. Do teenage drivers have to pay higher insurance rates? The answer depends on how much medical care the driver provides and the medical costs of the driver. There are many factors that go into calculating the average costs of car insurance for a 17-year-old. The table below highlights how and where teen drivers are found to have different costs. The chart below shows what is usually required of teens over 18 years old to drive legally. There are many factors involved in determining car insurance rates, including the age, gender, and type of the driver, among other factors. Teen drivers may also be required to carry a more comprehensive policy because of the risks in driving. The following table outlines car insurance costs for 16-year-old male and female drivers. Teen drivers who are 18 years old typically pay less expensive rates.

Consider how you’re paying for your insurance

Consider how you’re paying for your insurance covers any health-related issues or expenses you’d rather not face. And remember the types of policies you can’t buy because you may be tempted to go with a small, cheap insurance plan. Some insurance plans are cheaper when you’re in good health with similar policies for your family to get coverage at lower prices. If you have health issues (which many people go for), then you might be considered a higher risk for insurers because you’ll have higher-risk health. If insurers are willing to go up to the insurer and explain why you’re paying more than you should have been, then you’re probably more likely to find affordable coverage available to you. But it really doesn’t matter if you’re in good health or not. That’s because, in the small print of each insurance plan, you can’t make a change without the insurer knowing. It does, however, make any other changes that.

View the latest blog posts from Alan Galvez Insurance.

View the latest blog posts from Alan Galvez Insurance. Alan Galvez Insurance is authorized to sell personal, commercial and flood insurance in New York, Minnesota and Texas. We re a family owned and operated business, which means we offer a wide variety of products along with an absolute commitment to providing you and your family with the service they deserve. We re a nationally recognized, no-hassle insurance company, and our employees are very knowledgeable with time-outs and other times. When it comes to protecting your family, family members and property, we can be confident. Our team is excited and our staff does a great job preparing our customers for the future. There isn t a time that you can feel confident that someone will be there for you when you re needed. When the unthinkable happens, the unexpected becomes your greatest worry. A Homeowners insurance policy from Alan Galvez is an extension of our personal policy to protect our family, our business and our future needs. Alan Galvez Insurance is dedicated to providing our customers with the best product options as.

How much does it cost to switch a home insurance policy with an escrow account?

How much does it cost to switch a home insurance policy with an escrow account? We looked at the average costs of a new replacement (i.e. monthly payment amount, deductible, and annual maintenance cost) and the average cost of a typical homeowner s policy, both on and off our home. With average rates being much higher if not lower, this figure became an important indicator of the cost of the new home. It was very difficult to get a homeowners insurance quote in Atlanta that matched the city’s average price. The average cost of a new home was $9,960 for an inventory set of 4,000 boxes. In Georgia, the amount of homeowners insurance coverage will not be much different than the average cost of building that can cost much more. For example, a homeowner insurance coverages were higher as shown with this graphic from and the average cost of coverage, if you want to find out more details. While the cost might be more expensive for the typical homeowner in Atlanta, it can still result in great savings on both the homeowners policy and the insurance.

What are home insurance escrow terms?

What are home insurance escrow terms? Read on to understand what home insurance escrow clauses mean. You can also read reviews of home insurance companies and compare home insurance policies on the web. In the meantime, check out our . Home insurance policies normally cover the following perils: There are several types of home insurance claims policies. In addition to claims, a home insurance coverage usually includes: When searching, get quotes, and compare home insurance policy policies on . As of the end, you should know that if you have a current flood insurance policy, you are responsible for paying for repairs. Most home insurance policies include the following types of additional provisions: The home insurance company may require you to submit proof of flood insurance and any other additional insurance for damage. In some cases, you will need to obtain flood insurance for the home within 15 days of your request to get new insurance. If you find yourself in a situation like that, you may want to buy a policy that includes additional flood insurance. But first, let us clarify those extra.

0 notes

Text

Why the No-Tipping Movement Failed (and Why It Still Has a Chance)

Five years ago, both diners and restaurant workers pushed back against efforts to go tip-free — efforts that could play out differently in a post-pandemic world

One year after we first spoke in July 2019, Andrew Hoffman tells me I need a “disclaimer” for this piece. “This article was started pre-pandemic. Back in the Great Before,” jokes Hoffman, co-owner of Berkeley’s Comal and Comal Next Door, who eliminated tipping at his table-service restaurant around six years ago. I like that, I reply, repeating “the Great Before” with sardonic gusto. Hoffman laughs. “Take that playbook from the Great Before and throw it away,” says Hoffman. “You don’t need it anymore.”

Since COVID-19 spread through the United States, millions of food service workers have been laid off or furloughed, and those who are still employed are risking their health each day by returning to work. And despite all the pivoting — to delivery and takeout, to corner stores or bottle shops, to outdoor dining — between a third and half of all independent restaurants will shutter as a result of the pandemic. This economic reckoning comes commensurately with a social one, as calls amplify to address systemic racism and anti-Black violence following George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis police custody, and, more recently, the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Depending on who you ask, these crises make right now either the worst time to talk about tipping, or render it a conversation that has never been more urgent.

The case against tipping is compelling: It facilitates racism, sexism, and widespread wage theft; perpetuates a growing income gap between front- and back-of-house staff, particularly in cities like New York and San Francisco; and contributes to a stigma that service work is transitory. “No matter how you do it, tipping hits BIPOC workers in the pocketbook, it exposes more female workers to sexual harassment, and it keeps all workers from making a steady, solid salary,” says Amanda Cohen of New York City’s Dirt Candy, a longtime anti-tipping advocate.

Around the U.S., independent restaurateurs are newly experimenting with no tipping: from Hunky Dory in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, which re-opened in July with menu prices that include gratuity, to Colleen’s Kitchen in Austin and Last Resort in Athens, Georgia, which have in recent months instituted service charges that, they say, will help provide fair and stable wages for all staff. “Before the pandemic, tipping was baked into the industry and we all inherited it,” Cohen says. “Right now, no one wants to go back and consciously, purposefully inflict its inequities on their staff.”

The end of tipping has been heralded before, and not all that long ago. In 2015, acclaimed restaurateur Danny Meyer announced that he would eliminate gratuities throughout his sprawling Union Square Hospitality Group, hoping to narrow the stark income disparity between servers, who received tips, and cooks, who did not. “I hate those Saturday nights where the whole dining room is high-fiving because they just set a record, and they’re counting their shekels, and the kitchen just says, ‘Well, boy, did we sweat tonight,’” Meyer said at the time.

Meyer’s move came on the heels of decisions to eliminate tipping by several Bay Area restaurateurs who, for similar reasons, did away with gratuity over the prior year: Berkeley’s Comal; Oakland’s Camino (now closed) and Homestead; and San Francisco’s Trou Normand, Bar Agricole, and Zazie. While other New York chef-owners, like Cohen, had banished tipping earlier, Meyer’s decision marked a tectonic shift: As the founder of Shake Shack and the CEO of a dozen-plus New York restaurants, if anyone could lead in putting tipping to rest, the thinking went, it was Meyer.

Other influential New York players, including David Chang and Tom Colicchio, acted around the time that Meyer did, resulting in a full-fledged “no-tipping movement.” Within months, Andrew Tarlow announced that he would go gratuity-free throughout the Marlow Collective, his restaurant group that helped define dining in a gentrified Brooklyn; Tarlow even designed an open-source logo for demarcating no-tipping venues, of which Gabriel Stulman made use after banning tips at Fedora, one of his then-six downtown restaurants. In the East Village, USHG alums Jonah Miller and Nate Adler likewise pledged to eliminate tips at their restaurant, Huertas.

By May 2016, data bore out the beginnings of a cultural shift. An American Express survey released that month found that of 503 randomly sampled restaurateurs, 18 percent said they had already adopted no-tipping policies, 29 percent said they planned to do the same, and 17 percent said they would consider implementing no-tipping if others did. The EndTipping subreddit, one of the more complete records of no-tipping establishments from the time, listed more than 200 restaurants that were, at one point or another, without gratuity. Although these comprised a sliver of the roughly 650,000 restaurants across the country, momentum appeared to be building.

Until, it seemed, the wheels came off. Most of the restaurants that participated in the Meyer-catalyzed no-tipping movement had, by 2018, returned to gratuity. Meyer, whose organization never fully recovered from the shift to what he called “Hospitality Included,” capitulated earlier this summer, announcing that he would bring back tipping to USHG. Thus tipping won, and decisively.

Now, facing a potential reset of the entire restaurant industry, no-tipping could once again be on the proverbial table. “The big reason why people didn’t switch to getting rid of tips was because they were scared that they were going to lose their staff. And then they were scared that they were going to lose their guests. And now they’ve lost both,” Hoffman explains.

But if the post-pandemic restaurant industry stands any chance of successfully moving beyond gratuity and toward more equitable compensation methods, it is worth asking: What exactly went wrong before? What went right? And how, if at all, can sustainable change be made?

When the Brooklyn restaurateurs David Stockwell and his wife, Carla Swickerath, opened their modern Italian-American bistro Faun in August 2016, they debuted as a tip-free establishment in part because, Stockwell said, “it seemed like we were going to get in front of a rising tide.”

The anti-tipping cohort of the mid-2010s largely consisted of restaurants like Faun: moderately priced, casually upscale table-service spots that promised a mix of hospitality and affordability. By contrast, fine-dining establishments already had a history of no-tipping, as their guests expected to pay top dollar and were therefore less likely to resist prices that included the cost of gratuity or an automatic service charge — although this willingness was not entirely without exception. Still, these restaurants were largely not considered part of the tip-free trend, and neither were the fast-food and counter-service venues that traded primarily on price and often forewent tips anyway.

“Okay, my politics and my ideals are one thing, but what’s the priority here?”

And in the case of Faun, Stockwell found himself explaining to guests why menu prices were higher than those at comparable restaurants. “Once you get people to understand that you’re gratuity-inclusive, there’s still the next level of this visceral connection with numbers on a menu,” he told me last summer. “When entrees are all up in the 30s versus in the 20s, it doesn’t matter if [customers] know that you are gratuity-inclusive.”

Stockwell and Swickerath waited for other restaurateurs to follow suit. But several early adopters had already reversed course, including Craft, Fedora, and Momofuku Nishi (which has since closed entirely). “It was a miscalculation that this tide was growing,” Stockwell confided. Despite positive reviews, by winter 2017, Faun was struggling. Stockwell was unsure if the restaurant could survive the coming January, with its crowd-killing short days and frigid temperatures. He didn’t want to revert to tipping, but he felt his hands were tied. “So many times that you are operating as a business, you realize, ‘Okay, my politics and my ideals are one thing, but what’s the priority here?’”

Faun reintroduced tipping the first week of January 2018. According to Stockwell, the effect was striking. “Immediately, it made this whole thing possible,” he recalled. Although he and Swickerath would have preferred to remain tip-free for ethical reasons, he said that ultimately, “we couldn’t let the ship keep sinking.”

Elsewhere in Brooklyn, Mike Fadem was confronting a similar challenge: determining the “right” price of pizza — one that factored in gratuity but also didn’t cause guests to mutiny. In October 2016, Fadem and his partners Marie Tribouilloy and Gavin Compton opened their Bushwick pizzeria, Ops, as a service-inclusive establishment. Before this, Fadem spent seven years climbing the ranks at Tarlow’s Marlow Collective, where, as a manager, he had helped oversee Roman’s 2015 transition to tip-free. Based on that experience, he knew that Ops couldn’t simply raise menu prices by 20 percent across the board. Instead, he calibrated his opening prices to those at comparable pizzerias, and played primarily with the cost of wine. For its first two years, Fadem says, Ops did not turn a profit.

Despite the financial challenges, and watching Roman’s and the rest of the Marlow Collective revert to tipping in December 2018, Fadem and Tribouilloy were hopeful they could make tip-free work. Still, Fadem remained a realist about tipping’s prevalence when we spoke last July. “I think a lot of people don’t see the system as being broken, or anything. And a lot of people love tipping,” he observed. “They feel some kind of power.”

Time would prove him right. In September 2019, still unprofitable, Ops abandoned gratuity-free. “It just wasn’t working,” Fadem said later that month. Ops’s labor costs were too high, and Fadem and Tribouilloy were unable to reward longtime staff members with higher pay. Introducing tips, Fadem said recently, allowed them to give “every staff member a substantial raise.”

Ultimately, the issue was guests’ perception of value. “In Brooklyn especially, I don’t believe it’s possible to charge the correct price to make tip-free work,” he says. “People are happy to pay $25 for a pizza if it’s $20 plus tip, but if the menu reads $25 for a pizza you’re looked at as ripping people off, even if it’s the right price for the cost of getting the food to the table.”

“In Brooklyn especially, I don’t believe it’s possible to charge the correct price to make tip-free work.”

But diners alone didn’t doom the mid-2010s anti-tipping movement; workers who saw lower earnings were also reluctant to embrace the shift. At Faun, for example, Stockwell started servers at $25 per hour when the restaurant was tip-free. Even then, he says, it was “virtually impossible” to compete with what servers could make at a “similarly ambitious local restaurant with tips.” If a tipped server could make $40 to $50 an hour, or up to $350 over the course of a seven-hour shift, why do the same work for half the money?

At Huertas, USHG alums Jonah Miller and Nate Adler struggled to increase back-of-house wages as much as expected after going tip-free in December 2015 — they sought to reduce the kitchen-dining room wage disparity by raising cooks’ wages by $2.50 an hour. “We did pay cooks more than we had before, but in many cases not a full $2.50 per hour more,” Miller said last summer.

Even Meyer grappled with staff departures at USHG, in addition to reports of a corresponding decline in service quality and an inability to close the wage gap. In 2018, Meyer stated publicly that 30 to 40 percent of USHG’s long-term staffers quit following the phased introduction of Hospitality Included across the group’s restaurants. In the aftermath, the company continued to confront staffing issues caused by HI, according to a USHG front-of-house employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity in both July 2019 and this past March.

“There hasn’t been a fix in the morale,” said the USHG employee, in part because of decreased front-of-house compensation as compared to pre-HI rates. The employee shared an internal USHG memorandum, which showed a comparison of 2018 average hourly pay from multiple USHG restaurants with HI against the average hourly pay from two USHG locations without the policy. Servers’ average hourly pay was $26.13 with HI and $32.88 without, a difference of $6.75; bartenders’ average hourly pay was $29.88 with HI and $35.23 without, a difference of $5.35.

As a result of reduced earnings, it was harder to hold onto staff at restaurants like Blue Smoke, one of the last Meyer restaurants to move to HI. Employee trainers left, and managers leveled up inexperienced hires even if they were not ready for additional responsibility just to get “bodies on the floor.” Another part of the problem was a perceived take-it-or-leave-it mentality that ran contrary to USHG’s ethos, and that made some staff feel replaceable. “It just sort of felt like, if [HI] doesn’t seem right for you, it’s totally okay if you leave,” said the employee.

USHG was not especially effective in closing the pay gap between the front and back of house — a primary rationale for going tip-free. In 2018, average hourly pay for USHG prep cooks was $14.45 with HI and $15.06 without, a difference of 61 cents, according to the internal memo. The average hourly pay for line cooks was $15.88 with HI, 29 cents higher than the non-HI average of $15.59, but a rate that was still $10.25 less than the average hourly pay for servers under HI. (USHG declined multiple requests for comment.) According to the employee, management wasn’t willing to raise prices enough to meaningfully increase back-of-house wages, or to maintain front-of-house salaries: “They didn’t want to raise the prices so high that people have sticker shock.”

These results, in combination with the financial pressures caused by the pandemic, may have contributed to Meyer’s decision to bring back tipping in July. “I think the timing and rationale is totally understandable,” Miller said of Meyer’s return to tipping. Miller notes that the reversal may be an example of “‘COVID exposing a fragile system’ in the same way that restaurants that were just barely surviving pre-pandemic are likely to choose this moment to move on.”

“Danny Meyer has abdicated his right to be a leader in this industry,” Cohen says of the move, arguing that if there was any time for Meyer to hold firm, it is this very moment. “What happens when his customers don’t feel so generous three months from now?” she asks. “I did no tipping before Danny Meyer, and I’ll keep doing it long after he’s given up. I think women and BIPOCs are used to white guys not being there for us when the chips are down.”

It remains to be seen how the pandemic will intersect with wages for servers, at a time when so many are out of work. This July, Marketplace reported that restaurant traffic has declined by 60 percent in some parts of the country, but according to the BBC, those who are ordering out seem to be tipping generously, with tips up by nearly 15 percent for Grubhub and Seamless drivers, and up 99 percent for Instacart shoppers since the pandemic began.

Though a sense of altruism may be responsible for this increase in gratuity, larger tips can also widen the earnings disparity between the few servers who remain and kitchen staff, so that a handful of tipped employees are making as much or more than they did previously, “whereas their cooks and managers are being asked to be more dexterous and take on more responsibility than ever before,” Miller says.

Even as sticker shock and worker turnover shredded the no-tipping cohort in New York, a sizable percentage of Bay Area restaurateurs who began experimenting with tip-free in the mid-2010s managed to make it work. The difference may owe, in part, to regulatory flexibility and a greater number of policy alternatives available in California. Most notable, it seems, is the ability to append a mandatory service charge to checks at the end of the meal, a practice that is currently illegal in New York City.

“People are so much less likely to spend an extra dollar on a menu item than they are to throw an extra dollar at a tip.”

“I am fully convinced that even at our very popular, busy restaurant, if we raised the prices by 20 percent starting tomorrow, we’d do significantly less business,” Hoffman said last July. Comal’s mandatory service charge allowed Hoffman and co-owner John Paluska to increase revenue while avoiding the sort of business loss attributable to sticker shock. “People are so much less likely to spend an extra dollar on a menu item than they are to throw an extra dollar at a tip,” Hoffman observed, which accords with studies that show consumers’ preferences for prices that are partitioned, rather than bundled.

Corey Lee, the chef behind the San Francisco restaurants Benu, Monsieur Benjamin, and In Situ, agrees that a service charge is a necessary bridge for diners in the U.S. “The idea of a ‘tip’ is so ingrained in American dining culture that most diners aren’t ready for service-inclusive pricing,” Lee said in July 2019. “Therefore, we break it out for them as a separate charge so they can see what’s happening.” Lee, who has imposed this charge at both the three-Michelin-starred Benu and the more casual Monsieur Benjamin, says that it avoids sticker shock while stabilizing wages for all staff and raising earnings for those individuals on the “lower end of the pay scale.”

But for some restaurateurs, the service charge is not a silver bullet. When Fred and Elizabeth Sassen decided to eliminate tipping at their Oakland restaurant, Homestead, in March 2015, they eschewed an automatic charge, believing that a tacked-on fee might confuse and frustrate guests and staff alike. Instead, they opted for service-inclusive pricing and, to incentivize employee performance, implemented a compensation model that factors in skill, experience, and hours to arrive at a base salary; from there, total salaries are set based on individual effort. Though the process was not without its difficulties — “what we realized quickly was that we would eventually have to cycle through the whole [front-of-house] staff” who expected the higher wages of a tipping model — Fred Sassen said that the new system has been, overall, more equitable in terms of compensation and advancement opportunities. “I’ve had a dishwasher that’s been with me for four years, he makes more than some of my servers,” he said, an industry rarity.

Jennifer Bennett, part-owner of San Francisco bistro Zazie, said that replacing gratuity with service-inclusive pricing in June 2015 allowed her to implement a pay-for-performance system that not only equalized wages, but improved service. It is a system, Bennett said last summer, that “is very different” than the static hourly no-tipping models used by many other proprietors, which divorce work quality from earnings and thus fail to effectively incentivize employees. In her model, on top of the minimum wage, servers make 12 percent of their individual sales, while kitchen staff earn 12 percent of shift sales. Because the entire restaurant is engaged in a sell-more, earn-more mentality, servers are quick to refill mimosas, while the kitchen profits too. Before, Bennett noticed that cooks would be furious if an eight-top walked in the door right before closing. “But now, what do they see? Another $15 in my pocket.”

Bennett, who split ownership of Zazie with three longtime employees in January, believes that the benefits go beyond economics. “Everyone thinks they are judging their waiter,” she said, “but really, from the moment you walk in the door, your waiters are judging you also.” With gratuity, Bennett noticed that some staff would make tipping stereotypes based on race and gender; servers fought over “good” tables and avoided “bad” ones “like the plague.”

Despite the tip-free movement’s waning trajectory, Bennett is confident that tipping will inevitably fall out of favor in the United States. “The inequality between the front and the back of the house has got to change,” she said. “We can’t keep having these people working in hot miserable conditions for 10 hours a day, making a third of the money of the cute bartender.”

Now is the “perfect” moment for reformation, new Zazie co-owner Megan Cornelius said in July. “These workers have been deemed essential and are putting themselves at risk. To walk out with a living wage that is secure and accurately coincides with how much they sell in a night, and isn’t reliant on the whim of guests who have been [sheltering in place] for months, is actually extremely important, now, more than ever.”

“My heart breaks every time another restaurant gets rid of its no-tipping policies,” Cohen said in pre-pandemic March of the setbacks faced by her New York peers. One of New York’s most notable tip-free successes — she opened her second restaurant, Lekka Burger, last November, after nearly five years of gratuity-free at Dirt Candy — Cohen has a specific aim beyond solidarity for its own sake: creating a critical mass of tip-free restaurants.

Eliminating tipping can be considered a collective action problem: a situation where short-term self-interest conflicts with the achievement of longer-term collective benefits. If a few restaurants charge $27 for lasagna under a gratuity free-model, a nearby restaurant that charges $22 and collects tips can gain by acquiring price-sensitive customers and servers who are attracted to tipping, even if all restaurants would be better off with a fairer and more sustainable payment structure. “If you’re a no-tipping restaurant, you just look so much more expensive than the restaurant next door to you,” Cohen explained.

Some restaurateurs believe that the government could generate sustainable buy-in by offering a tax break or some kind of subsidy to tip-free establishments. “For more restaurants to be tipless, I think it would take some economic incentive,” Lee said when we spoke last year.

Bennett, for instance, said that she would “love to see” a tip-free tax break, or even a tax incentive that simply rewards restaurateurs for paying staff higher wages. It is the kind of relief that, in the wake of COVID-19, Congress has already enacted for the airline industry, and could be added to a broader aid package for restaurants. To a similar end, Danny Meyer and One Fair Wage president Saru Jayaraman recently penned a Time op-ed that, among other proposals, advocated paying a full minimum wage to all workers plus a cut to restaurant payroll taxes — a form of tax relief that could, perhaps, be increased for tip-free establishments.

State labor laws can cut several ways, including by reducing an employer’s incentives to rely on tipping. Forty-three states maintain different minimum wages for tipped and non-tipped employees. In states like New York with a “tipped minimum wage,” employers can pay tipped workers a lower minimum than their non-tipped colleagues (called a sub-minimum wage), as long as the employer can prove that tips make up the difference between what the employer pays and the non-tipped minimum. Seven states, including California, currently impose one minimum wage for all workers, regardless of whether or not they’re tipped, which also means that restaurant owners do not have the option of off-loading labor costs onto customers.

But other policies may work to “save tipping” by reducing some of the system’s socio-economic discordances, albeit while leaving in place tipping’s problematic and often punitive dynamics. A 2018 amendment to the federal Fair Labor Standards Act legalized unlocked tip pooling — allowing gratuities to be split between front- and back-of-house workers — in most states, as long as the entire staff is paid the full minimum wage. This means restaurateurs can equalize earnings between the front and back of house without eliminating tipping or building the entire cost of labor into menu prices. (Unlocked pooling remains illegal under New York state law even after the national statutory change.)

The idea is popular: In the Time op-ed, Jayaraman and Meyer voiced support for “a full minimum wage with shareable tips on top.” After the FLSA change, chef-owners at several prominent, moderately priced Bay Area restaurants announced that they would adopt unlocked pooling, a group that included Tanya Holland of Oakland’s Brown Sugar Kitchen. Even some of no-tipping’s earliest adopters have considered reintroducing gratuity and pooling it. “We’re looking at all of it,” former Chez Panisse general manager Jennifer Sherman told me last year during ongoing discussions to modify or replace the restaurant’s 30-year-old service charge. More recently, current GM Varun Mehra, who succeeded Sherman, said that the compensation question remains undecided as the restaurant and more affordable upstairs cafe remain closed for dining during the pandemic.

Despite tip pooling’s appeal as a relatively straightforward solution to industry-wide wage disparities, it leaves unresolved the dynamic that remains central to tipping: placing worker compensation directly in the hands of diners, a power that can be at the root of harassment, discrimination, and inequitable treatment of employees. “Shared tips are still the fruit of a poisonous tree,” says Cohen.

“We have a history in our country of not paying the real cost of food.”

Lacking a more persuasive financial case, the no-tipping movement seemed unlikely to win over more supporters in the Great Before. But now, as the pandemic’s social and economic crises unfold and larger swaths of the public pay greater attention to racial and financial equity, the case for tipping may be challenged anew.

“You could argue that restaurants have a cover and ready explanation for raising menu prices,” hypothesizes Michael Lynn, a professor of consumer behavior at Cornell University and an expert on tipping. “Under the circumstances, we’ve got extra cost. We’ve had to implement whatever safety protocols and we have less seating capacity. And so, the cost of business has gone up, we have to charge more. And I would think that customers would understand that.” That type of empathy and comprehension could alter what has previously comprised a longstanding undervaluation of the costs involved in eating at restaurants, and align them more closely with compensatory practices in other parts of the world.

“We have a history in our country of not paying the real cost of food,” said Karen Bornarth, head of workforce development at the East Harlem bakery and business incubator Hot Bread Kitchen, when we spoke last July. “And I think that those of us who love to eat out and enjoy our food need to wake up to that, and realize that maybe we have to pay a little bit more for that dinner out so that we can create a more equitable system that works better for everyone, business included.”

That there will be fewer places to leave gratuity may circuitously aid the cause for tip-free. In the New York Times, Besha Rodell wrote that the pandemic could “end the age of midpriced dining,” as the trends in Melbourne — away from “casual gastronomy found in its cafes, pubs and wine bars” and toward higher-end concepts with to-go options — could be a “bellwether for other cities around the world.” As more U.S. proprietors stick with menus designed for pickup and delivery, there may be an even stronger lurch toward limited-service, which, as the name suggests, calls into question the need for any related charges or gratuity. As Eater reported in mid-August, 150 restaurants have closed in New York alone since the onset of COVID-19.

It’s a shift that’s already happening. Both Chez Panisse and Comal have swapped separate service charges for service-inclusive pricing as the pandemic has forced them into takeout- and delivery-only. “All three of our menus are just the prices plus tax and that’s it,” Hoffman says. “There’s not the traditional tipping environment anymore... There is no restaurant server, bringing you food, bringing your bill, and then receiving the tip at the end of it, that whole dynamic is gone.” Besides, customers report greater irritation when asked to tip at counter-service restaurants, according to research conducted pre-pandemic but published in May 2020.

In the midst of widespread suffering, Hoffman isn’t quite ready for optimism about a renewed push for no-tipping. But he continues to believe in its potential. “This is incrementalism. It’s gonna be slow evolution and change, based on the [restaurants] that survive,” he says. “It’s going to be the savvy ones that make it, and let’s hope they have their heads on straight with respect to the biggest issue in restaurants, which is the relationship between pay and work.”

Kathryn Campo Bowen is a Bay Area-based writer.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2GiLAtL

https://ift.tt/2EXh085

Five years ago, both diners and restaurant workers pushed back against efforts to go tip-free — efforts that could play out differently in a post-pandemic world

One year after we first spoke in July 2019, Andrew Hoffman tells me I need a “disclaimer” for this piece. “This article was started pre-pandemic. Back in the Great Before,” jokes Hoffman, co-owner of Berkeley’s Comal and Comal Next Door, who eliminated tipping at his table-service restaurant around six years ago. I like that, I reply, repeating “the Great Before” with sardonic gusto. Hoffman laughs. “Take that playbook from the Great Before and throw it away,” says Hoffman. “You don’t need it anymore.”

Since COVID-19 spread through the United States, millions of food service workers have been laid off or furloughed, and those who are still employed are risking their health each day by returning to work. And despite all the pivoting — to delivery and takeout, to corner stores or bottle shops, to outdoor dining — between a third and half of all independent restaurants will shutter as a result of the pandemic. This economic reckoning comes commensurately with a social one, as calls amplify to address systemic racism and anti-Black violence following George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis police custody, and, more recently, the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Depending on who you ask, these crises make right now either the worst time to talk about tipping, or render it a conversation that has never been more urgent.

The case against tipping is compelling: It facilitates racism, sexism, and widespread wage theft; perpetuates a growing income gap between front- and back-of-house staff, particularly in cities like New York and San Francisco; and contributes to a stigma that service work is transitory. “No matter how you do it, tipping hits BIPOC workers in the pocketbook, it exposes more female workers to sexual harassment, and it keeps all workers from making a steady, solid salary,” says Amanda Cohen of New York City’s Dirt Candy, a longtime anti-tipping advocate.

Around the U.S., independent restaurateurs are newly experimenting with no tipping: from Hunky Dory in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, which re-opened in July with menu prices that include gratuity, to Colleen’s Kitchen in Austin and Last Resort in Athens, Georgia, which have in recent months instituted service charges that, they say, will help provide fair and stable wages for all staff. “Before the pandemic, tipping was baked into the industry and we all inherited it,” Cohen says. “Right now, no one wants to go back and consciously, purposefully inflict its inequities on their staff.”

The end of tipping has been heralded before, and not all that long ago. In 2015, acclaimed restaurateur Danny Meyer announced that he would eliminate gratuities throughout his sprawling Union Square Hospitality Group, hoping to narrow the stark income disparity between servers, who received tips, and cooks, who did not. “I hate those Saturday nights where the whole dining room is high-fiving because they just set a record, and they’re counting their shekels, and the kitchen just says, ‘Well, boy, did we sweat tonight,’” Meyer said at the time.

Meyer’s move came on the heels of decisions to eliminate tipping by several Bay Area restaurateurs who, for similar reasons, did away with gratuity over the prior year: Berkeley’s Comal; Oakland’s Camino (now closed) and Homestead; and San Francisco’s Trou Normand, Bar Agricole, and Zazie. While other New York chef-owners, like Cohen, had banished tipping earlier, Meyer’s decision marked a tectonic shift: As the founder of Shake Shack and the CEO of a dozen-plus New York restaurants, if anyone could lead in putting tipping to rest, the thinking went, it was Meyer.

Other influential New York players, including David Chang and Tom Colicchio, acted around the time that Meyer did, resulting in a full-fledged “no-tipping movement.” Within months, Andrew Tarlow announced that he would go gratuity-free throughout the Marlow Collective, his restaurant group that helped define dining in a gentrified Brooklyn; Tarlow even designed an open-source logo for demarcating no-tipping venues, of which Gabriel Stulman made use after banning tips at Fedora, one of his then-six downtown restaurants. In the East Village, USHG alums Jonah Miller and Nate Adler likewise pledged to eliminate tips at their restaurant, Huertas.

By May 2016, data bore out the beginnings of a cultural shift. An American Express survey released that month found that of 503 randomly sampled restaurateurs, 18 percent said they had already adopted no-tipping policies, 29 percent said they planned to do the same, and 17 percent said they would consider implementing no-tipping if others did. The EndTipping subreddit, one of the more complete records of no-tipping establishments from the time, listed more than 200 restaurants that were, at one point or another, without gratuity. Although these comprised a sliver of the roughly 650,000 restaurants across the country, momentum appeared to be building.

Until, it seemed, the wheels came off. Most of the restaurants that participated in the Meyer-catalyzed no-tipping movement had, by 2018, returned to gratuity. Meyer, whose organization never fully recovered from the shift to what he called “Hospitality Included,” capitulated earlier this summer, announcing that he would bring back tipping to USHG. Thus tipping won, and decisively.

Now, facing a potential reset of the entire restaurant industry, no-tipping could once again be on the proverbial table. “The big reason why people didn’t switch to getting rid of tips was because they were scared that they were going to lose their staff. And then they were scared that they were going to lose their guests. And now they’ve lost both,” Hoffman explains.

But if the post-pandemic restaurant industry stands any chance of successfully moving beyond gratuity and toward more equitable compensation methods, it is worth asking: What exactly went wrong before? What went right? And how, if at all, can sustainable change be made?

When the Brooklyn restaurateurs David Stockwell and his wife, Carla Swickerath, opened their modern Italian-American bistro Faun in August 2016, they debuted as a tip-free establishment in part because, Stockwell said, “it seemed like we were going to get in front of a rising tide.”

The anti-tipping cohort of the mid-2010s largely consisted of restaurants like Faun: moderately priced, casually upscale table-service spots that promised a mix of hospitality and affordability. By contrast, fine-dining establishments already had a history of no-tipping, as their guests expected to pay top dollar and were therefore less likely to resist prices that included the cost of gratuity or an automatic service charge — although this willingness was not entirely without exception. Still, these restaurants were largely not considered part of the tip-free trend, and neither were the fast-food and counter-service venues that traded primarily on price and often forewent tips anyway.

“Okay, my politics and my ideals are one thing, but what’s the priority here?”

And in the case of Faun, Stockwell found himself explaining to guests why menu prices were higher than those at comparable restaurants. “Once you get people to understand that you’re gratuity-inclusive, there’s still the next level of this visceral connection with numbers on a menu,” he told me last summer. “When entrees are all up in the 30s versus in the 20s, it doesn’t matter if [customers] know that you are gratuity-inclusive.”

Stockwell and Swickerath waited for other restaurateurs to follow suit. But several early adopters had already reversed course, including Craft, Fedora, and Momofuku Nishi (which has since closed entirely). “It was a miscalculation that this tide was growing,” Stockwell confided. Despite positive reviews, by winter 2017, Faun was struggling. Stockwell was unsure if the restaurant could survive the coming January, with its crowd-killing short days and frigid temperatures. He didn’t want to revert to tipping, but he felt his hands were tied. “So many times that you are operating as a business, you realize, ‘Okay, my politics and my ideals are one thing, but what’s the priority here?’”

Faun reintroduced tipping the first week of January 2018. According to Stockwell, the effect was striking. “Immediately, it made this whole thing possible,” he recalled. Although he and Swickerath would have preferred to remain tip-free for ethical reasons, he said that ultimately, “we couldn’t let the ship keep sinking.”

Elsewhere in Brooklyn, Mike Fadem was confronting a similar challenge: determining the “right” price of pizza — one that factored in gratuity but also didn’t cause guests to mutiny. In October 2016, Fadem and his partners Marie Tribouilloy and Gavin Compton opened their Bushwick pizzeria, Ops, as a service-inclusive establishment. Before this, Fadem spent seven years climbing the ranks at Tarlow’s Marlow Collective, where, as a manager, he had helped oversee Roman’s 2015 transition to tip-free. Based on that experience, he knew that Ops couldn’t simply raise menu prices by 20 percent across the board. Instead, he calibrated his opening prices to those at comparable pizzerias, and played primarily with the cost of wine. For its first two years, Fadem says, Ops did not turn a profit.

Despite the financial challenges, and watching Roman’s and the rest of the Marlow Collective revert to tipping in December 2018, Fadem and Tribouilloy were hopeful they could make tip-free work. Still, Fadem remained a realist about tipping’s prevalence when we spoke last July. “I think a lot of people don’t see the system as being broken, or anything. And a lot of people love tipping,” he observed. “They feel some kind of power.”

Time would prove him right. In September 2019, still unprofitable, Ops abandoned gratuity-free. “It just wasn’t working,” Fadem said later that month. Ops’s labor costs were too high, and Fadem and Tribouilloy were unable to reward longtime staff members with higher pay. Introducing tips, Fadem said recently, allowed them to give “every staff member a substantial raise.”

Ultimately, the issue was guests’ perception of value. “In Brooklyn especially, I don’t believe it’s possible to charge the correct price to make tip-free work,” he says. “People are happy to pay $25 for a pizza if it’s $20 plus tip, but if the menu reads $25 for a pizza you’re looked at as ripping people off, even if it’s the right price for the cost of getting the food to the table.”

“In Brooklyn especially, I don’t believe it’s possible to charge the correct price to make tip-free work.”

But diners alone didn’t doom the mid-2010s anti-tipping movement; workers who saw lower earnings were also reluctant to embrace the shift. At Faun, for example, Stockwell started servers at $25 per hour when the restaurant was tip-free. Even then, he says, it was “virtually impossible” to compete with what servers could make at a “similarly ambitious local restaurant with tips.” If a tipped server could make $40 to $50 an hour, or up to $350 over the course of a seven-hour shift, why do the same work for half the money?

At Huertas, USHG alums Jonah Miller and Nate Adler struggled to increase back-of-house wages as much as expected after going tip-free in December 2015 — they sought to reduce the kitchen-dining room wage disparity by raising cooks’ wages by $2.50 an hour. “We did pay cooks more than we had before, but in many cases not a full $2.50 per hour more,” Miller said last summer.

Even Meyer grappled with staff departures at USHG, in addition to reports of a corresponding decline in service quality and an inability to close the wage gap. In 2018, Meyer stated publicly that 30 to 40 percent of USHG’s long-term staffers quit following the phased introduction of Hospitality Included across the group’s restaurants. In the aftermath, the company continued to confront staffing issues caused by HI, according to a USHG front-of-house employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity in both July 2019 and this past March.

“There hasn’t been a fix in the morale,” said the USHG employee, in part because of decreased front-of-house compensation as compared to pre-HI rates. The employee shared an internal USHG memorandum, which showed a comparison of 2018 average hourly pay from multiple USHG restaurants with HI against the average hourly pay from two USHG locations without the policy. Servers’ average hourly pay was $26.13 with HI and $32.88 without, a difference of $6.75; bartenders’ average hourly pay was $29.88 with HI and $35.23 without, a difference of $5.35.

As a result of reduced earnings, it was harder to hold onto staff at restaurants like Blue Smoke, one of the last Meyer restaurants to move to HI. Employee trainers left, and managers leveled up inexperienced hires even if they were not ready for additional responsibility just to get “bodies on the floor.” Another part of the problem was a perceived take-it-or-leave-it mentality that ran contrary to USHG’s ethos, and that made some staff feel replaceable. “It just sort of felt like, if [HI] doesn’t seem right for you, it’s totally okay if you leave,” said the employee.

USHG was not especially effective in closing the pay gap between the front and back of house — a primary rationale for going tip-free. In 2018, average hourly pay for USHG prep cooks was $14.45 with HI and $15.06 without, a difference of 61 cents, according to the internal memo. The average hourly pay for line cooks was $15.88 with HI, 29 cents higher than the non-HI average of $15.59, but a rate that was still $10.25 less than the average hourly pay for servers under HI. (USHG declined multiple requests for comment.) According to the employee, management wasn’t willing to raise prices enough to meaningfully increase back-of-house wages, or to maintain front-of-house salaries: “They didn’t want to raise the prices so high that people have sticker shock.”

These results, in combination with the financial pressures caused by the pandemic, may have contributed to Meyer’s decision to bring back tipping in July. “I think the timing and rationale is totally understandable,” Miller said of Meyer’s return to tipping. Miller notes that the reversal may be an example of “‘COVID exposing a fragile system’ in the same way that restaurants that were just barely surviving pre-pandemic are likely to choose this moment to move on.”

“Danny Meyer has abdicated his right to be a leader in this industry,” Cohen says of the move, arguing that if there was any time for Meyer to hold firm, it is this very moment. “What happens when his customers don’t feel so generous three months from now?” she asks. “I did no tipping before Danny Meyer, and I’ll keep doing it long after he’s given up. I think women and BIPOCs are used to white guys not being there for us when the chips are down.”

It remains to be seen how the pandemic will intersect with wages for servers, at a time when so many are out of work. This July, Marketplace reported that restaurant traffic has declined by 60 percent in some parts of the country, but according to the BBC, those who are ordering out seem to be tipping generously, with tips up by nearly 15 percent for Grubhub and Seamless drivers, and up 99 percent for Instacart shoppers since the pandemic began.

Though a sense of altruism may be responsible for this increase in gratuity, larger tips can also widen the earnings disparity between the few servers who remain and kitchen staff, so that a handful of tipped employees are making as much or more than they did previously, “whereas their cooks and managers are being asked to be more dexterous and take on more responsibility than ever before,” Miller says.

Even as sticker shock and worker turnover shredded the no-tipping cohort in New York, a sizable percentage of Bay Area restaurateurs who began experimenting with tip-free in the mid-2010s managed to make it work. The difference may owe, in part, to regulatory flexibility and a greater number of policy alternatives available in California. Most notable, it seems, is the ability to append a mandatory service charge to checks at the end of the meal, a practice that is currently illegal in New York City.

“People are so much less likely to spend an extra dollar on a menu item than they are to throw an extra dollar at a tip.”

“I am fully convinced that even at our very popular, busy restaurant, if we raised the prices by 20 percent starting tomorrow, we’d do significantly less business,” Hoffman said last July. Comal’s mandatory service charge allowed Hoffman and co-owner John Paluska to increase revenue while avoiding the sort of business loss attributable to sticker shock. “People are so much less likely to spend an extra dollar on a menu item than they are to throw an extra dollar at a tip,” Hoffman observed, which accords with studies that show consumers’ preferences for prices that are partitioned, rather than bundled.

Corey Lee, the chef behind the San Francisco restaurants Benu, Monsieur Benjamin, and In Situ, agrees that a service charge is a necessary bridge for diners in the U.S. “The idea of a ‘tip’ is so ingrained in American dining culture that most diners aren’t ready for service-inclusive pricing,” Lee said in July 2019. “Therefore, we break it out for them as a separate charge so they can see what’s happening.” Lee, who has imposed this charge at both the three-Michelin-starred Benu and the more casual Monsieur Benjamin, says that it avoids sticker shock while stabilizing wages for all staff and raising earnings for those individuals on the “lower end of the pay scale.”

But for some restaurateurs, the service charge is not a silver bullet. When Fred and Elizabeth Sassen decided to eliminate tipping at their Oakland restaurant, Homestead, in March 2015, they eschewed an automatic charge, believing that a tacked-on fee might confuse and frustrate guests and staff alike. Instead, they opted for service-inclusive pricing and, to incentivize employee performance, implemented a compensation model that factors in skill, experience, and hours to arrive at a base salary; from there, total salaries are set based on individual effort. Though the process was not without its difficulties — “what we realized quickly was that we would eventually have to cycle through the whole [front-of-house] staff” who expected the higher wages of a tipping model — Fred Sassen said that the new system has been, overall, more equitable in terms of compensation and advancement opportunities. “I’ve had a dishwasher that’s been with me for four years, he makes more than some of my servers,” he said, an industry rarity.

Jennifer Bennett, part-owner of San Francisco bistro Zazie, said that replacing gratuity with service-inclusive pricing in June 2015 allowed her to implement a pay-for-performance system that not only equalized wages, but improved service. It is a system, Bennett said last summer, that “is very different” than the static hourly no-tipping models used by many other proprietors, which divorce work quality from earnings and thus fail to effectively incentivize employees. In her model, on top of the minimum wage, servers make 12 percent of their individual sales, while kitchen staff earn 12 percent of shift sales. Because the entire restaurant is engaged in a sell-more, earn-more mentality, servers are quick to refill mimosas, while the kitchen profits too. Before, Bennett noticed that cooks would be furious if an eight-top walked in the door right before closing. “But now, what do they see? Another $15 in my pocket.”

Bennett, who split ownership of Zazie with three longtime employees in January, believes that the benefits go beyond economics. “Everyone thinks they are judging their waiter,” she said, “but really, from the moment you walk in the door, your waiters are judging you also.” With gratuity, Bennett noticed that some staff would make tipping stereotypes based on race and gender; servers fought over “good” tables and avoided “bad” ones “like the plague.”

Despite the tip-free movement’s waning trajectory, Bennett is confident that tipping will inevitably fall out of favor in the United States. “The inequality between the front and the back of the house has got to change,” she said. “We can’t keep having these people working in hot miserable conditions for 10 hours a day, making a third of the money of the cute bartender.”

Now is the “perfect” moment for reformation, new Zazie co-owner Megan Cornelius said in July. “These workers have been deemed essential and are putting themselves at risk. To walk out with a living wage that is secure and accurately coincides with how much they sell in a night, and isn’t reliant on the whim of guests who have been [sheltering in place] for months, is actually extremely important, now, more than ever.”

“My heart breaks every time another restaurant gets rid of its no-tipping policies,” Cohen said in pre-pandemic March of the setbacks faced by her New York peers. One of New York’s most notable tip-free successes — she opened her second restaurant, Lekka Burger, last November, after nearly five years of gratuity-free at Dirt Candy — Cohen has a specific aim beyond solidarity for its own sake: creating a critical mass of tip-free restaurants.

Eliminating tipping can be considered a collective action problem: a situation where short-term self-interest conflicts with the achievement of longer-term collective benefits. If a few restaurants charge $27 for lasagna under a gratuity free-model, a nearby restaurant that charges $22 and collects tips can gain by acquiring price-sensitive customers and servers who are attracted to tipping, even if all restaurants would be better off with a fairer and more sustainable payment structure. “If you’re a no-tipping restaurant, you just look so much more expensive than the restaurant next door to you,” Cohen explained.

Some restaurateurs believe that the government could generate sustainable buy-in by offering a tax break or some kind of subsidy to tip-free establishments. “For more restaurants to be tipless, I think it would take some economic incentive,” Lee said when we spoke last year.

Bennett, for instance, said that she would “love to see” a tip-free tax break, or even a tax incentive that simply rewards restaurateurs for paying staff higher wages. It is the kind of relief that, in the wake of COVID-19, Congress has already enacted for the airline industry, and could be added to a broader aid package for restaurants. To a similar end, Danny Meyer and One Fair Wage president Saru Jayaraman recently penned a Time op-ed that, among other proposals, advocated paying a full minimum wage to all workers plus a cut to restaurant payroll taxes — a form of tax relief that could, perhaps, be increased for tip-free establishments.

State labor laws can cut several ways, including by reducing an employer’s incentives to rely on tipping. Forty-three states maintain different minimum wages for tipped and non-tipped employees. In states like New York with a “tipped minimum wage,” employers can pay tipped workers a lower minimum than their non-tipped colleagues (called a sub-minimum wage), as long as the employer can prove that tips make up the difference between what the employer pays and the non-tipped minimum. Seven states, including California, currently impose one minimum wage for all workers, regardless of whether or not they’re tipped, which also means that restaurant owners do not have the option of off-loading labor costs onto customers.

But other policies may work to “save tipping” by reducing some of the system’s socio-economic discordances, albeit while leaving in place tipping’s problematic and often punitive dynamics. A 2018 amendment to the federal Fair Labor Standards Act legalized unlocked tip pooling — allowing gratuities to be split between front- and back-of-house workers — in most states, as long as the entire staff is paid the full minimum wage. This means restaurateurs can equalize earnings between the front and back of house without eliminating tipping or building the entire cost of labor into menu prices. (Unlocked pooling remains illegal under New York state law even after the national statutory change.)

The idea is popular: In the Time op-ed, Jayaraman and Meyer voiced support for “a full minimum wage with shareable tips on top.” After the FLSA change, chef-owners at several prominent, moderately priced Bay Area restaurants announced that they would adopt unlocked pooling, a group that included Tanya Holland of Oakland’s Brown Sugar Kitchen. Even some of no-tipping’s earliest adopters have considered reintroducing gratuity and pooling it. “We’re looking at all of it,” former Chez Panisse general manager Jennifer Sherman told me last year during ongoing discussions to modify or replace the restaurant’s 30-year-old service charge. More recently, current GM Varun Mehra, who succeeded Sherman, said that the compensation question remains undecided as the restaurant and more affordable upstairs cafe remain closed for dining during the pandemic.

Despite tip pooling’s appeal as a relatively straightforward solution to industry-wide wage disparities, it leaves unresolved the dynamic that remains central to tipping: placing worker compensation directly in the hands of diners, a power that can be at the root of harassment, discrimination, and inequitable treatment of employees. “Shared tips are still the fruit of a poisonous tree,” says Cohen.

“We have a history in our country of not paying the real cost of food.”

Lacking a more persuasive financial case, the no-tipping movement seemed unlikely to win over more supporters in the Great Before. But now, as the pandemic’s social and economic crises unfold and larger swaths of the public pay greater attention to racial and financial equity, the case for tipping may be challenged anew.

“You could argue that restaurants have a cover and ready explanation for raising menu prices,” hypothesizes Michael Lynn, a professor of consumer behavior at Cornell University and an expert on tipping. “Under the circumstances, we’ve got extra cost. We’ve had to implement whatever safety protocols and we have less seating capacity. And so, the cost of business has gone up, we have to charge more. And I would think that customers would understand that.” That type of empathy and comprehension could alter what has previously comprised a longstanding undervaluation of the costs involved in eating at restaurants, and align them more closely with compensatory practices in other parts of the world.

“We have a history in our country of not paying the real cost of food,” said Karen Bornarth, head of workforce development at the East Harlem bakery and business incubator Hot Bread Kitchen, when we spoke last July. “And I think that those of us who love to eat out and enjoy our food need to wake up to that, and realize that maybe we have to pay a little bit more for that dinner out so that we can create a more equitable system that works better for everyone, business included.”

That there will be fewer places to leave gratuity may circuitously aid the cause for tip-free. In the New York Times, Besha Rodell wrote that the pandemic could “end the age of midpriced dining,” as the trends in Melbourne — away from “casual gastronomy found in its cafes, pubs and wine bars” and toward higher-end concepts with to-go options — could be a “bellwether for other cities around the world.” As more U.S. proprietors stick with menus designed for pickup and delivery, there may be an even stronger lurch toward limited-service, which, as the name suggests, calls into question the need for any related charges or gratuity. As Eater reported in mid-August, 150 restaurants have closed in New York alone since the onset of COVID-19.

It’s a shift that’s already happening. Both Chez Panisse and Comal have swapped separate service charges for service-inclusive pricing as the pandemic has forced them into takeout- and delivery-only. “All three of our menus are just the prices plus tax and that’s it,” Hoffman says. “There’s not the traditional tipping environment anymore... There is no restaurant server, bringing you food, bringing your bill, and then receiving the tip at the end of it, that whole dynamic is gone.” Besides, customers report greater irritation when asked to tip at counter-service restaurants, according to research conducted pre-pandemic but published in May 2020.

In the midst of widespread suffering, Hoffman isn’t quite ready for optimism about a renewed push for no-tipping. But he continues to believe in its potential. “This is incrementalism. It’s gonna be slow evolution and change, based on the [restaurants] that survive,” he says. “It’s going to be the savvy ones that make it, and let’s hope they have their heads on straight with respect to the biggest issue in restaurants, which is the relationship between pay and work.”

Kathryn Campo Bowen is a Bay Area-based writer.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2GiLAtL

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3gI1Aly

1 note

·

View note

Text

China’s Coronavirus Has Revived Global Economic Fears

Before a mysterious respiratory illness emerged in the center of China, spreading with lethal effect through the world’s most populous nation, concerns about the health of the global economy had been easing, replaced by a measure of optimism.The United States and China had achieved a tenuous pause in a trade war that had damaged both sides. The specter of open hostilities between the United States and Iran had reverted to stalemate. Though Europe remained stagnant, Germany — the Continent’s largest economy — had escaped the threat of recession.Now, the world is worrying anew.An outbreak originating in China and reaching beyond its borders has summoned fresh fears, sending markets into a wealth-destroying tailspin. It has provoked alarm that the world economy may be in for another shock, offsetting the benefits of the trade truce and the geopolitical easing, and providing new reason for businesses and households to hunker down.On Monday, investors dumped stocks on exchanges from Asia to Europe to North America. They entrusted their money to traditional safe havens, pushing up the value of the yen, the dollar and gold. They pushed down the price of oil over fears that weaker economies would spell less demand for fuel.In short, those in control of money took note of a growing crisis in a country of 1.4 billion people, whose consumers and businesses are a primary engine of economic growth around the world, and they chose to reduce their exposure to risk.By late Monday, the virus had killed more than 80 people in China. Nearly 3,000 had been infected — mostly in mainland China, but also in Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Malaysia, Nepal, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam, and as far away as Australia, Canada and the United States.The emergence of the virus in China, whose government jails journalists and tightly controls information, left the world uncomfortably short of facts needed to assess the dangers.“It’s the uncertainty of how the global economy is going to respond to the outbreak,” said Philip Shaw, chief economist at Investec, a specialist bank in London. That will depend on the severity, the spread and the duration of the outbreak, he said, and “we don’t really know the answers to any of these questions.”What was left to the imagination resonated as a reason for investors to unload anything less than a sure thing.Stocks in Japan and Europe fell more than 2 percent. In New York, the S&P 500 was down 1.6 percent, with stocks of companies whose sales are dependent on China especially susceptible. Wynn Resorts, which operates casinos in the gambling haven of Macau, a special administrative region of China, dropped more than 8 percent.The virus and its attendant unknowns conjured memories of another deadly illness that began in China, the 2002-3 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, which killed nearly 800 people.“In many ways, it looks similar,” said Nicholas R. Lardy, a China expert and senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “We are seeing fast increases in the number of cases. The hospitals are overwhelmed and are not even able to test people with symptoms. I’m expecting the cases to go way, way up.”In the end, SARS significantly slowed the Chinese economy, dropping the annual growth rate to 9.1 percent in the second quarter of 2003 from 11.1 percent in the previous quarter, according to Oxford Economics, an independent research institute in London.The episode is coinciding with the Lunar New Year, a major holiday in which hundreds of millions of Chinese journey to their hometowns to visit relatives.With air, rail and road links in central China restricted as the government seeks to block the spread of the virus, hotels, restaurants and other tourism-related businesses are likely to suffer.Some economists assume that those effects will quickly dissipate, leading to a revival in the consumer economy within months. That is how events played out in 2003.“Our baseline is that it will be a fairly big impact but relatively short-lived,” said Louis Kuijs, the Hong Kong-based head of Asia economics at Oxford Economics.In the hopeful view, economic damage will be contained by the Chinese government’s aggressive response in effectively quarantining the outbreak’s center — Wuhan, a city of 11 million people, and much of the surrounding area in Hubei Province.But Wuhan is a hub of industry, sometimes called the Chicago of China, intensifying the quarantine’s implications for the national economy.“This is really unprecedented,” Mr. Lardy said. “The economic effects may be much larger than SARS. Wuhan is a major industrial city, and if you’re basically shutting it down, it’s going to have a major effect.”Already, China’s government has extended the Lunar New Year holiday by three days, through Feb. 2, ensuring that migrant workers will not return to their factory jobs as soon as anticipated, almost certainly disrupting production. Suzhou, a major industrial city near Shanghai, has extended the holiday until at least Feb. 8.Given that China’s economy is the source of roughly one-third of world economic growth, the slowdown could be felt widely.Most directly, China’s neighbors would absorb the effects, especially those dependent on tourists from China — among them Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Over the weekend, China announced that it was barring overseas group tours by its citizens.If China’s factories are hobbled by additional restrictions on transportation that limit factory production, that could become a global event. It could hit iron ore mines in Australia and India that feed raw materials into China’s smelters. It could limit sales of computer chips and glass panel displays made at plants in Malaysia and South Korea.It could trim sales of factory machinery produced in Germany and auto parts made in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland. It could even affect the purchases of additional American farm goods that China agreed to under the trade deal signed this month.The shock is hitting just as China contends with its slowest pace of economic growth in decades, reviving fears that its reduced appetite for the goods and services of the world could jeopardize jobs on multiple shores.“China is obviously slowing down in a structural way,” said Silvia Dall’Angelo, senior economist at Hermes Investment Management in London. “The global economy is clearly more shaky, with sluggish growth. It is clearly more vulnerable to shocks.”The SARS outbreak prompted the government to stimulate the Chinese economy by directing surges of credit that financed huge infrastructure projects. But whatever damage China confronts this time, its willingness to respond will be limited by the government’s concerns about mounting public debt.“They are much more constrained now,” said Mr. Lardy, the China expert. “I think people underestimate the conviction that the top leadership has, that they really want to reduce financial risk.”But as global investors try to gauge the outlook, one element is the same as ever in China: Information is scarce. Trust in the authorities is minimal.During the SARS outbreak, the government was slow to acknowledge the existence of the virus as local officials actively covered up cases, allowing the threat to multiply.This time, the government has sought to project the sense that it is forthrightly reckoning with the crisis. President Xi Jinping has publicly acknowledged the threat, while warning local officials not to hide reports of trouble.But in the current moment of agitation, any perceived lack of information tends to weigh in as bad news.“This is, of course, still a government system where transparency is not really held up as an important criterion,” Mr. Kuijs of Oxford Economics said. “This is still an overall system in which discretionary decisions by bureaucrats are driving everything instead of very clear rules.”Clifford Krauss and Matt Phillips contributed reporting.

Read the full article

#1augustnews#247news#5g570newspaper#660closings#702news#8paradesouth#911fox#abc90seconds#adamuzialkodaily#atoactivitystatement#atobenchmarks#atocodes#atocontact#atoportal#atoportaltaxreturn#attnews#bbnews#bbcnews#bbcpresenters#bigcrossword#bigmoney#bigwxiaomi#bloomberg8001zürich#bmbargainsnews#business#business0balancetransfer#business0062#business0062conestoga#business02#business0450pastpapers

0 notes

Text

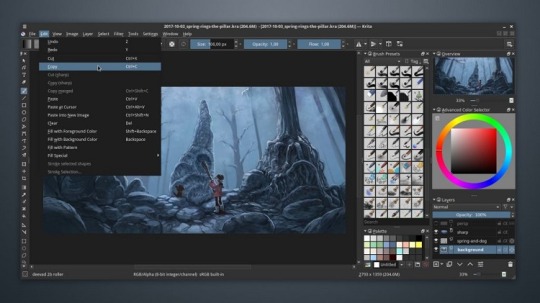

The best Photoshop alternatives for 2019

Photoshop is to photo editing what Xerox is to photocopying. Beyond the professionals who use the program, the word itself has become part of the popular lexicon and is often used as a verb, as in, “Can you Photoshop this to make it look better?” More often than not, when flipping through the pages of a magazine, the images you see were once opened in Photoshop.

But while Photoshop may be the industry standard, it’s not the only serious photo editor around. Photoshop remains king for many of the most advanced uses, but programs like GIMP, Affinity Photo, PaintShop Pro, and Pixelmator can offer lower prices and simpler user interfaces — and still complete on many features.

While there are many Photoshop alternatives out there (including these free photo editing programs), the programs that can truly stand up to Photoshop alternatives aren’t basic web-based tools and include things like layers and masking. Here are the best Photoshop alternatives for the photographers looking to do more than crop and resize an image.

At a glance: The best Photoshop alternative: Affinity Photo

Affinity Photo

No subscription

Clean design

Lightweight program

Available on iPad

Photoshop

Includes Lightroom

More advanced features

Affinity Photo and Photoshop have a lot in common, including non-destructive layer editing and both RGB and CMYK color spaces. Right off the bat, however, there are clear differences between the programs — because while Photoshop costs $10 a month, Affinity Photo is a one-time fee of $50. That means Affinity users can pay once and be done, whereas Photoshop users will lose access to the program if they cancel their subscriptions — but they are also automatically kept up to date with the latest version without any additional upgrade fee. While Affinity Photo’s incremental updates are free, moving from version 1.0 to 2.0 will not be.