#I think it's important for us as climate activists to remember to take joy in spring

Photo

“ At any rate, spring is here, even in London N.1, and they can’t stop you enjoying it...The atom bombs are piling up in the factories, the police are prowling through the cities, the lies are streaming from the loudspeakers, but the earth is still going round the sun, and neither the dictators nor the bureaucrats, deeply as they disapprove of the process, are able to prevent it“ - George Orwell, Some Thoughts On The Common Toad, 1946

Happy belated May Day!

#environmentalism#nature#global warming#climate change#climate crisis#spring#plants#george orwell#thoughts on the common toad#based on photos I took in Los Angeles though Orwell's essay is about London I guess#I think it's important for us as climate activists to remember to take joy in spring#even when it's so easy to look at warming weather as just another reason to despair

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dreamers (2021)

Working toward a better world, a world of racial justice and an end to interlocking oppressions, requires imagination. On this weekend when we remember the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., let's also consider both the history of civil rights and the unbounded creativity of speculative fiction by writers of color as sources of inspiration.

Expanded and revised for the Washington Ethical Society, presented January 17, 2021.

“We are creating a world we have never seen,” writes Adrienne Maree Brown in Emergent Strategy. On this weekend, as we remember the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., support a peaceful transfer of power, and recommit to his legacy and the work of civil rights yet to do, it may seem like a luxury or a distraction to engage with imagination. It is not. Just like we cannot allow oppression to steal our joy, we cannot let it steal our imagination. Neither threats of violence, nor attempts to push us into re-creating a fictional and regressive society of the past, nor manufactured austerity preventing relief from reaching working people, nor white supremacy in any form should be allowed to steal our imagination. Our ability to dream of a better world is a matter of collective survival.

What does it take to dream big? What fuels our ability to imagine a future without limits like racism, classism, and sexism? Entering a dream state where equality is possible takes some practice. Music can get us there. Listening to activists who are moving our society forward can help us get into that frame of mind. Great art can invite us into that kind of transformational trance.

Dreaming is important. Dreaming gives us creativity, energy, and a warm vision around which we can gather a community. Dreaming is not enough. Once we have imagined a better world, we have to (we get to) build it, to keep building it, and to rebuild the parts that got torn down when we weren’t paying attention. The next step is to use those dreams as a doorway to action.

Dr. King’s words and actions demonstrated connections between systemic racial inequality, economic injustice, war, threats to labor rights, and blockades to voting rights. All of those forces are still relevant. He and the other activists of his era left a very rich legacy, for which we are grateful. We are not done.

I’ll be drawing today from Dr. King’s 1963 work, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” (Also available as an audio file from the King Institute.) I think the critiques he offered in that letter are still valid, especially for us in this community that strives to be anti-racist and yet must acknowledge that we are impacted by the norms of what King calls, “the white moderate.” His letter was a response to Christian and Jewish clergy, who had written an open letter criticizing nonviolent direct action. Though Ethical Culture uses different language and methods than our explicitly theist neighbors, I think it is incumbent upon us to hold on to the accountability that comes with being part of the interfaith community. So I believe this letter is written to us as well. Dr. King wrote:

I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the … great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time; and who constantly advises [us] to wait until a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

I would like to think that, in this community, we have made some progress since 1963, and that majority-white communities have stopped explicitly trying to slow the pace of civil rights. Indeed, WES can be proud that racial justice has been woven into its goals from the beginning, though we must also be honest that a perfectly anti-racist history is unlikely. At the same time, I see people who claim to be progressive rushing to calls for “civility” or “unity” without accountability. Understanding the direct link between the intended audience of this letter and the people and communities with which we have kinship today is an act of imagination that we must embrace in order to learn from the past and to continue Dr. King’s legacy. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” can help us understand why we need to dream of something different in the world.

We need dreams and we need plans. We seek inspiration as we continue to work toward bringing a dream of economic and political equality fully into reality.

One place I turn for inspiration is toward socially conscious science fiction. Looking at how the art form has offered critiques of what’s wrong and pathways to what’s right, I see suggestions for how we can nurture the dream of a better world.

Science fiction has even helped me understand spiritually-connected social movements, such as the one depicted in Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler. The series depicts a self-governing poetic community that tries to live sustainably in an environment affected by catastrophic climate change, and that maintains an improbable vision of exploring the stars. The poetry uses the word God, but not in the way that it is normally used. Recognizing that WES is not a community that makes use of theism, I hope you’ll be able to hear how that metaphor is used in the world of the story. In Parable of the Talents, the main character, Lauren Olamina, writes a poem for her community:

God is change

And hidden within change

Is surprise, delight,

Confusion, pain,

Discovery, loss,

Opportunity and growth.

As always, God exists

To shape

And to be shaped

(Parable of the Talents, p. 92)

In the book, the community that reflects on change in meditation and song is able to use that energy to maintain resilience, even in the face of white supremacist violence and criminalization. Butler imagines an inclusive community led by People of Color who strengthen and encourage one another, inject their strategic planning with an expectation for backlash, and still imagine and make their way toward a better world. Her books provide inspiration to those who know that the negative extremes of the world of the story are possible.

Socially conscious science fiction spins dreams that are extreme, that challenge us in good ways. In science fiction and in practical experience with progressive movements, we learn that dreams need help to become reality.

The alternate universe where justice rolls down like water may seem too fantastic to believe, it may be cobbled together in ways that seem mis-matched to mundane perceptions, and it will certainly take work to achieve. Nevertheless, like Dr. King, I believe “we must use time creatively.”

Dreams Are Extreme

The first thing to note about dreams, whether sleeping or socially conscious, is that they are extreme. Things that would be totally absurd or unthinkable in everyday reality are woven into the fabric of a new vision. The dream might be a positive one, in which we imagine what it would be like to live in a better world. On the other hand, dystopian dreams can also be effective at stirring us to action. In an imagined world, we are met with the possibility that a flaw in our current society might go too far. Absurdity comes uncomfortably close to the truth.

Dr. King spoke about the role of discomfort in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” saying that nonviolent direct action is meant to bring that discomfort to bear so that those in power will sit down and negotiate, to recognize people of good conscience. This is different from using violence as coercion, which is destructive to democracy; this is using peaceful means to declare the right of people to have a voice in what concerns them. Dr. King writes:

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension that a community that has consistently refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. I just referred to the creation of tension as a part of the work of the nonviolent resister. This may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly worked and preached against violent tension, but there is a type of constructive nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth.

Tension has a place in literature and drama that can also be used for racial justice. I once served as an intern at a regional theater. In one of the plays we presented that year, the plot hinged on something unexplainable and highly improbable, which is one definition for science fiction. It was the 1965 play Day of Absence by African American playwright Douglas Turner Ward. In the story, white citizens of a racist town awaken one day to find that all of the African American residents have mysteriously disappeared. They slowly come to realize that they cannot function without the neighbors they mistreated and took for granted. Rather than try to solve their problems, they spend the rest of the play panicking and blaming each other in comedic ways.

Between the satirical script, the exaggerated makeup, and the abstract set, the show turns reality inside out in an effort to alter the audience’s collective conscience. Day of Absence shines a spotlight on the links between racial oppression and economic oppression, and is an incitement to join a movement for change. Consistent with the Revolutionary Theatre aesthetic, the play is meant to make people uncomfortable. We should be uncomfortable with the real systems of inequality parodied in the play.

It worked. Audiences were uncomfortable. Some patrons were able to take that discomfort and use it to grow. Some patrons were not ready to deal productively with their discomfort. For art or spirituality or dreams or anything else to offer the chance for transformation, creating the opportunity can’t wait until everyone is equally ready to begin the journey.

One goal of satire is to take something that is true and to exaggerate it until the truth cannot be ignored. When that something is oppression, making art that can’t be ignored and suggesting a justice-oriented overhaul to society is going to seem extreme to some people.

Speculative fiction by writers of color, even when not satirical, can also use exaggeration for a positive effect. The 2019 HBO Watchmen series explored this, creating an alternate history that lifted out problems with racism and policing in our own timeline. The Broken Earth trilogy by N.K. Jemisin explores extremes of climate change and identity-based exploitation, and weaves in glimpses of generational trauma between parents and children trying to survive in a society that rejects their wholeness. Extremes in literature can reflect back to us the plain truth.

Similarly, a dream that draws people together for the hope of a society that is very different from what we have, a dream that re-imagines the future of justice and economic opportunity, is going to be considered extreme, which is not a good thing by some standards. Every time there is a popular movie or TV show in the science fiction/fantasy genre that uses multiracial casting, and every time a speculative fiction novel by a writer of color receives sales or awards, there are claims that social justice warriors are running amok, or that trends have gone too far. Allowing for multiracial imagination is considered a violation of balance, a bridge too far. Inclusion is considered extreme, rather than a tool for bringing imagined futures into being.

Dr. King explored this critique of extremism. In “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” he expresses some initial frustration at being labeled an extremist for his peaceful methods. It seemed that any movement toward change was too radical for the white moderate clergy. But the status quo was not and is not acceptable. Dr. King writes:

So I have not said to my people: "Get rid of your discontent." Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: "Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you." … (Dr. King gives a few more examples before he goes on.) So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? … Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists. (paragraph 24)

I believe the nation and the world are in need of creative extremists. We need dreamers. We need bold playwrights, courageous writers, and artists who cannot be ignored. We need the power to imagine a more just and radically different future.

Dreams Need Help to Become Reality

Another point that connects science fiction with visions of equality is that dreams need help to become reality. We hear often that “the arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” but the unwritten part of that is that actual people have to do some bending. Dr. King wrote about that, too; though he uses “man” in a way that was common at the time to mean people of all genders, and he invokes his own religious tradition, we can all hear the collective responsibility in this passage. In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King wrote:

Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right. Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy and transform our pending national elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. Now is the time to lift our national policy from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of human dignity. (paragraph 21)

We can and should have hope. We still need to act according to our values. No act of encouragement, no vote cast, no letter written is a wasted effort. We must use time creatively. In the case of arts, literature, and entertainment, we must also use time travel creatively. Progress does not happen by accident.

Nichelle Nichols, who played Lieutenant Uhura in the original Star Trek series, spoke about the creation of her character and why she chose to stay on the show. None of it was an accident. When she first met with Gene Roddenberry, she was in the middle of reading a book on Uhuru, which is Swahili for freedom. Roddenberry became more convinced than ever that he wanted a Black woman on the bridge of the Enterprise. Nichols said:

When the show began and I was cast to develop this character – I was cast as one of the stars of the show – the reality of the matter was the industry was not ready for a woman or a Black and certainly not the combination of the two (and you have to remember this was 1966) in that kind of role, on that equal basis, and certainly not that kind of power role.

Nichols was also an accomplished singer and stage actress. The producers never told her about the volume of fan mail she was receiving. She was considering leaving the show to join a theatrical production headed for Broadway, when she was at an event (probably a fundraiser for the NAACP, but Nichols doesn’t remember clearly) and was asked to meet a fan. The fan turned out to be the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He told her how much he enjoyed the show, and that it was the only show he and his wife allowed their children to stay up late to watch. She told him that she was planning to resign. “You cannot!” he said. Nichols goes on:

Dr. King said to me, ‘Don’t you understand that you have the first non-stereotypical role in television in a major TV series of importance, and you establish us as we are supposed to be: as equals, whether it’s ethnic, racial, or gender.’ I was breathless. ‘Thank you, and Yes, I will stay.’

Nichols’ decision to stay had a ripple effect. Whoopi Goldberg said that the first time she saw Lieutenant Uhura on television was a major turning point for her as a child. Mae Jemison, the first African American astronaut in space, spoke about Uhura as an inspiration. Stacey Abrams is a fan.

The inner workings of a TV show with cheesy special effects, beloved as that show may be, might seem inconsequential to the future of human rights. I maintain that anything that expands our ability to dream of a better world is necessary. Stories that give us building blocks for change make a difference. And representation matters. People are hungry for diverse, respectful, innovative stories. Representation increases the chances that someone from a marginalized group can get the resources to tell their own stories rather than relying on the dominant group to borrow them. In this age of communication, it is possible to engage people from all over the planet in a conversation about our shared future. The trick is that we have to work to make sure all of the voices are included. The dream of a better world needs people who can make it a reality.

Imagination is key, and it is a starting point. In Emergent Strategy, Adrienne Maree Brown writes:

Science fiction is simply a way to practice the future together. I suspect that is what many of you are up to, practicing futures together, practicing justice together, living into new stories. It is our right and responsibility to create a new world. What we pay attention to grows, so I’m thinking about how we grow what we are all imagining and creating into something large enough and solid enough that it becomes a tipping point.

Earlier, you heard another quote from the book, in which Brown names the Beloved Community that we can use imagination to grow ourselves into. She names “a future without police and prisons ... a future without rape … harassment … constant fear, and childhood sexual assault. A future without war, hunger, violence. With abundance. Where gender is a joyful spectrum.”

Brown frames this imagined future world, this Beloved Community, as a project of both imagination and community organizing. A better world is possible.

Conclusion

The arts, in particular science fiction, can ignite a kind of a dream state. By using time and time-travel creatively, we can envision a world of justice, equality, and compassion. We have yet more ways to craft stories and plans that respect the inherent worth and dignity of every person. The dream of economic equality, the dream of equal voting rights, the dream of equal protection under the law all need foundations built under them.

If we wish to count ourselves among the dreamers, let us take action. We can continue to build coalitions with partner organizations of other faiths and cultures. We can send representatives to workshops and meetings, and listen carefully to their findings when they return. We can read about dismantling oppression and share what we find with each other.

This community is a place where we can dream freely. Let us use time effectively. Let us enter into the powers of myth, creativity, and art to imagine a better future. And then let us work and plan to make that better future come to pass. May our dreams refresh us and energize us for the tasks ahead.

May it be so.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Black Boys Bloom Thorns First: Volume 2, Chp. 23″

Summary: Erik makes a discovery that changes the course of his family forever...

NSFW. Mature Audience. Smut.

youtube

"Every once and awhile

I find myself going through a transition

Packing up, flying away again

Never knowing how or which way is up

Turning, Spinning high

Welcome to changes

No time to spare

Might as well get used to it

Welcome to changes

Blow with the air…"

Carleen Anderson – "Welcome to Changes"

Califia had known Dr. Barbara Davis since she was a child.

Therapy was something her grandmother insisted on after her father was arrested and sent to prison. Nana Jean understood that her granddaughter was traumatized and needed the professional help her mother couldn't give her.

Califia was grateful for the intervention and grateful to have used Dr. Davis services when she had a brutal fight with N'Jobu when they were in their twenties. It was the only time in their relationship where N'Jobu had laid hands on her. He was defending himself from her attack after he accused her of being a cheating slut. He claimed much later that he had been holding back, but she remembers him using ulwa on her without hesitation. Perhaps it was ingrained in him to protect himself with full force no matter who it was who attacked him.

Califia allowed the fingers of her left hand to fuss with the leather button on the couch she sat on in Dr. Davis's comfortable and welcoming office. Soft browns and mauves surrounded them with splashes of pink. Soothing colors in all the décor. Hanging plants with long green tendrils giving the space a safe feel.

Erik sat beside her, quiet, his hands in his lap as he waited for their session to begin.

N'Jobu had been home for months and their family had maintained a stable home life since his return. Califia had returned to work but she made sure she and Erik saw Dr. Davis twice a week.

"How are things going for you at school, Erik?"

Dr. Davis's kind eyes peered at him from her horn-rimmed glasses, a sweet smile on her lips as she looked at the boy. Erik's body shifted in his seat.

"Good," he said, "…better actually."

"How so?"

"I sleep better at home, so I'm…calmer…um, yeah…calmer at school. No more nightmares."

"That's good to hear. And you, Califia?"

Califia's eyes left Erik's face as she gazed at the therapist.

"I still get bad dreams…sometimes. Not of the attack, but just weird stuff that I can't remember when I wake up."

Dr. Davis scribbled some things down on a yellow notepad.

"What about N'Jobu? How has he been?"

"Good. He and Erik are going camping this weekend with Erik's friend Walter."

"We went to Disneyland a few weeks ago," Erik said. His face lit up at the memory.

Dr. Davis went over some new breathing techniques with them and showed them how to quickly assess their anxiety levels with each other. It hurt Califia so much that Erik suffered from some of the same problems that she grappled with as a child. Intergenerational trauma was no joke, and she worried that she had passed down so much of her pain to her son. Erik had always been a joy to raise, a sensitive little one who felt deeply, but Lia's assassination had opened a wound that accelerated anxiety in him. He was also showing signs of obsessive-compulsive behavior. She could see the stress in him as he tried in his own way to still process and live with what he witnessed.

Their fifty-minute session went by quickly and while Dr. Davis put away her notes, Califia felt her heart- rate go up.

"Erik, do me a favor, could you wait out in the next room. I want to schedule some things with your mother real quick," Dr. Davis said.

Erik nodded, hopped off the couch, and disappeared into the waiting room.

"Califia…what is it?"

Califia finally allowed her tears to flow freely. She kept them in so Erik wouldn't see them, struggling to look normal for him as he left the space.

"I'm messing him up," she said, her voice shuddering from suppressing her emotions from Erik.

"What makes you say that?"

Dr. Davis handed Califia a tissue to wipe her eyes.

"My entire life has been nothing but pain and struggle and mental health issues. I see what it's doing to him. I'm setting my baby up for failure. He's become so rigid about things and he treats me like I'm the child sometimes. He always checks to make sure I'm okay. I'm supposed to be doing that for him!"

She threw her hands over her face unable to stop herself from weeping.

"I've fucked up my son—"

"No…you haven't done that—"

"You see how he is—"

Dr. Davis pulled Califia's hands from her face.

"Let me tell you about your son. Erik witnessed a horrific event. But he is resilient. He has an absolute innate sense of justice. He believes strongly in fairness. He has a protective nature about him. His heart is so big and loving that he wants to make sure his Mommy is okay too."

Califia sat back on the couch still clutching the tissue in her hand.

"Parents can pass down anxiety—"

"That can happen. Erik has been displaying symptoms of an overactive brain, but it's nothing we can't work to improve. He's a brilliant child with big thoughts and ideas going on. He's learning to focus in much calmer ways so don't get yourself so worked up. Your coming here with him is the best thing you are doing to help him and yourself. His coping behaviors are simply coping behaviors. He could outgrow them over time—"

"What if he doesn't?"

"Let's focus on right now. Stressing over the future or the past is what keeps you stuck Califia. We work on that with you, and Erik will be fine. The fact that he sees you here doing your best to get well mentally only encourages him to do the same. You have to stay focused on the present with him now. Be mindful of the progress you both have made. Think of all the support you have from your family. Especially N'Jobu."

"Erik…he's my best thing, y'know?"

"I know."

"I worry so much about him. Parents are supposed to protect their children—"

"We live in the real world, Califia. You can't shield Erik from everything that happens, but you can be a pillar of strength and unconditional love for him. He can face anything when you and N'Jobu give him that."

Dr. Davis handed her another tissue and Califia tried to fix her face before going out to Erik.

Her son's eyes sought out hers the moment she walked out and he saw that they were pink from crying.

"You okay, Mom?"

"I am. Ready to go?"

"Yes."

She was mentally drained from the session and drove herself and Erik to visit N'Jobu at the shop. He was managing two new locations and they caught him as he returned to the original Drizzy's Kuts.

N'Jobu's eyes always lit up when he saw them and the moment they stepped into the shop, his arms were around her waist in greeting and he was touching Erik's hair.

"Hey, wasn't expecting you two to pop in," he said.

Califia sat in an open booth chair as Erik greeted three of the other barbers working on customers.

"Can I leave Erik here with you while I run over to see Rolita?"

"Sure. Is everything okay?"

"I got a text from her about meeting at her place with some of the women from Rise Up. Shouldn't take that long. An hour or two."

"Dinner at Nana's still?"

"Yeah."

She kissed his cheek and waved to Erik as she left. Needing Erik to be with the stronger parent right at the moment was important. She needed time with Rolita to lift herself up away from Erik. It was almost like he had extrasensory empath powers, able to read emotions and feelings from people just by looking in their eyes and taking on their weight. It was scary sometimes.

Rolita greeted her at her home with four other women from Rise Up and two men from a local Black activist group. There were snacks laid out in the living room and Califia ate chips from a paper plate with salsa. The mood in the room was solemn.

One of the men pulled out a laptop and showed the women a web page with a list of photos and names. Rolita sat next to Califia and took a deep breath.

"Activists are being murdered," Rolita said.

Califia felt the tension in the room rise.

"Misha Browning was found two hours ago," Rolita said and there was a gasp in the room from everyone.

Califia closed her eyes and steeled her nerves. Misha was a woman Califia had only known and interacted with online in cyber activist spaces. They had coordinated national action plans on police brutality and domestic terrorist attacks on immigrants and mutant humans. She had gone missing a few days previous and word spread by the police was that she had a domestic dispute with a boyfriend and disappeared soon after. But her boyfriend, a man Califia had met in person at a climate change conference in Fresno after she graduated university, was staying on a Scottish Island for a fellowship prior to Misha's disappearance.

There was a pattern.

Up until that moment, ten activists that Califia interacted with personally or knew of through online spaces nationally were dead. Seven of the dead were reported to have committed suicide. Four Black men and two Black women, and two Native women from the Pine Ridge Nation active with pipeline and environmental protests and civil disobedience. Three of them were said to have been murdered under suspicious circumstances. Their mental health was scrutinized and most of the newsfeed on them was swept away. Prominent and vocal activists. Killing themselves?

And now Misha. Found face down under Ohio river debris fifty miles away from her home.

Califia could only think of Lia and then her own self. Rolita too. They were mothers with young children. They were mothers trying to make the world safe for their babies. Could they be targeted next? Could they show up dead and the world told that they committed suicide? It wasn't unthinkable that an activist could kill themselves. Mental health was something they all grappled with and sometimes the world beat them down until killing oneself seemed like a good option. But ten people? Now eleven? Within two years?

Califia sat back in her seat. The rest of her time there long. And painful.

###

N'Jobu sat with Erik at his great-grandmother's kitchen table as he watched his son disassemble yet another one of his robotic toys. Erik had figured out a way to hack into the software of the original robotic programming and rebuild a new larger robot combining four different toys and the pieces of scrap metal his grandfather found for him. He placed the final pieces of the disassembled robot onto the final product.

Erik routed power to his new creation with a handheld and tried to get the strange-looking franken-robot to pick up a mug filled with tea and raise it up to N'Jobu's mouth. A set of spoons and a fork sat on the dining table waiting to be used by the robot to lift up a scoop of fruit loops and pick up sliced mango pieces.

"Be still, Baba." Erik said moving the levers in his hand.

N'Jobu sat still, but the tea mug didn't seem secure in the robot hand as small drops of the liquid spilled from the cup.

"I'm still, Son," he said trying not to laugh as the robot hand grew more unsteady.

"Stop laughing at it, you'll hurt the Daka 3000's feelings," Erik said.

"Oh, you changed its name again. Won't your mother be upset? The Cali 3000 was a nice-sounding name."

"Inventors name things after themselves."

"Why not JaJa 3000?"

"Too soft-sounding. The Daka in my middle name sounds hardcore…Baba, c'mon, be still!"

N'Jobu was leaning back in his seat, his hands up to catch the mug if it dropped.

"I have to perfect this by next week to be ready."

"Is Walter entering the science fair?"

"Yeah, he's working on something."

"You're not going to tell me about it?"

"It's boring."

"Don't say that about your friend."

"It is!"

"Tell me about it."

The robotic arm made it up to the front of N'Jobu's face with the mug. Erik did his best to ease it closer, but it was too jerky. He took a pause and stared at N'Jobu.

"He's making a display of fabrics that can be used to make flak jackets. Bulletproof—"

"So military science—"

"No, clothes for kids. So they won't be shot dead in school."

Whoa.

N'Jobu stared at Erik.

"He's really doing that?"

"Yeah. Lame."

"I don't think it's lame…just…that's pretty hardcore, Son."

"Compared to this? I'm creating a robot that can help the elderly in their homes. Open their pill bottles when they can't, feed them, and help put things away…but Walter's anti-kill clothes is hardcore. Serious Baba?"

"You both have created hardcore things."

"Kids shouldn't have to make clothes like that."

"I agree—"

"Like, make clothes that can let you fly or something…"

Frustrated, Erik snatched the mug from the robot's hand.

"I can't get this to move smoother. I'll have to take it apart. Wish I could get some nanobots for this…"

"Do you want to try the spoon or fork again? That did really well."

"Nah. Thanks for being my experimental human."

"Glad to be of help. Do me a favor though."

"Yeah?"

"Be supportive of Walter. He's trying to make something to help other children. Grown-ups are the blame for that, and it's a shame that a child his age wants to make something like that because we suck, but he is doing something he thinks is a good thing. Support that."

Erik stared at him and nodded his head.

"Who knows, maybe you both will make it to the Stark Expo. That would be exciting."

Erik grinned.

He was so determined to make his robot work. Not just for the Expo.

For Nana Jean.

His son's great-grandmother was ailing. Today she was having a good day and strong enough to make a Friday night fish fry. Relatives were coming over, and everyone was determined to make it a joyous evening of good food and family fun.

N'Jobu could see that the older woman was having a hard time with her health. Her once vibrant face was appearing a bit dull the last few months, and her already thin frame was looking gaunter. She was experiencing bouts of anger when she couldn't do a lot of things by herself like she used to. Like driving. She was having trouble with her hands, periodic shakiness and pain making it difficult for her on some days. But not today. Today she was cooking with the assistance of Erik and N'Jobu.

Erik picked up the tools he used to tweak the wires on his robot when he suddenly reached out and tapped on N'Jobu's kimoyo beads.

"It's lighting up, Baba!"

N'Jobu saw the emergency silver lighting on his beads. They warmed up his wrist.

"I've never seen that color before," Erik said, his eyes glued to his wrist.

The past three years he had told his son his beads were like mood rings and could change colors at will. But he was right. Silver was a new color. Silver was a signal from his fellow rogue War Dogs. Something was wrong.

"Clean this up, and we'll start making the batter for the fish and shrimp," he said.

Pushing back from the table, N'Jobu headed to a guest bedroom, Junie's old room, and locked the door.

"D'Beke," N'Jobu said, watching the man's shape hover over his wrist.

"We have found Klaue. He is ready to move into Wakanda. The time has come your Highness."

N'Jobu shut his eyes and sat on the guest bed.

"Send out a code three, and make sure all cells are on code. No more communications until you all hear from me. Understand? Send me Klaue's contact. We have to be…we have to be…D'Beke if anyone acts suspicious…end them."

"Yes, Prince N'Jobu."

D'Beke winked out and N'Jobu felt his body tremble with excitement and nervous energy.

The time had come to act. No more planning. Action.

"Wakanda Forever," he whispered.

###

Califia felt beyond stuffed. She rubbed her belly from all the shrimp she consumed. Hot, juicy, greasy, salty-sweet delicious shellfish fresh from the skillet. N'Jobu rubbed his belly and Califia watched Erik help Nana Jean fry up more shrimp in cornmeal batter this round.

"Nana. I can't eat anymore," she said.

Nana dropped shrimp into a fry strainer and Erik lowered it and stood back when the grease popped. Nana dropped more shrimp into the bowl filled with the batter.

"Someone will," Nana said, her frame so much smaller from how Califia always saw her as a little girl. She felt it deep down. No one else in the family wanted to say it outright, and Nana Jean was not forthcoming with her health, but Califia knew. Her great-grandmother was battling something and trying so hard to stay on the earth for Erik. That was her child. He may have come out of Califia's body, but Erik was her baby

Erik's mind was set on going to the Stark Expo in New York. He had come so close last year, making it to a semi-final status and receiving a signed certificate from Tony Stark himself. She and N'Jobu had to nurse him through a mini-temper tantrum when he didn't get to be a finalist. He pouted for weeks and wouldn't even hang up his certificate in his room that Nana Jean had framed for him. N'Jobu had to have a sit down with him and remind him of how many people, children, and adults had submitted projects and didn't even make it to the quarter-finals. She remembered the title of his abstract too, "Novel Subtle Acoustic Communication: Successful Elucidation of the Cryptic Ecology of Runner Plant Bugs with Emphasis on Their Stridulatory Mechanisms". He spent three months capturing the faint sound of bugs. Bugs that he had crawling all over his bedroom when a few escaped by accident. She shivered at the memory.

Califia had to chime in and show him the certificate.

"Tony Stark really signed this. A busy man like him took the time to sign something acknowledging your hard work. You should be proud of yourself."

It wasn't until Erik went online to see how many people had entered projects did his own parent's words kick in. There were only twenty-five semi-finalists for his category and his face beamed when he announced, "Just over half a million people entered globally."

For the new year, he switched from acoustics to robotics hoping to be a finalist. And he focused on something more personal, and close to home: Nana Jean.

That big ole heart of his wanted to make his Nana as self-sufficient for as long as possible with a personal elder care robot.

N'Jobu watched her closely after she rubbed her belly and caught his eye. Her mood hadn't been the best when she arrived at the house. The meeting at Rolita's was tough on her psyche and she almost opted to go home and sleep until her grandmother called Rolita reminding her to bring her daughter Neveah.

Erik's cousins and Neveah ran around the front room while Erik cooked at the stove.

"JaJa, go be with the other kids, I'll help Nana."

Erik nodded and she watched her grandmother pat his head.

"Nana, for reals, I don't think anyone else can eat more. Take a break and spend time out front too."

"Dayclean is still eating," she said.

"I am done, Nana. Go relax, we'll take care of all of this."

N'Jobu stood up and cleared the dishes left on the table as a few of Califia's Uncles cleaned up after themselves before heading to the den to watch TV.

"You good?" N'Jobu asked.

"Better."

"Erik told me you looked upset leaving your session today. Want to talk about it?"

"It was nothing serious…really. I was just feeling a way. Venting."

"Did it help?"

"I think so."

He rinsed dishes and stacked them in the new dishwasher they bought for Nana three years ago once they saw she had trouble with her hands.

She finished putting leftovers in the fridge and when she looked at N'Jobu again, his gentle eyes broke her down.

"Let's go in the back," he said when he saw her eyes well up with water.

The house was busy and no one paid them any mind going to the back guestroom. It was quiet back there. N'Jobu locked the door and they both sat on the bed.

Califia wiped her eyes.

"He is too much like me. And I am afraid for him."

"Califia—"

She touched his hand.

"His quick temper. His anxiety. His need to be in control…this compulsion to make things perfect…it's not healthy…and living here, and seeing Lia…I have damaged him."

N'Jobu stayed quiet and she was grateful. Over the years he had to learn how to let her talk things out and not try to offer immediate solutions as he was want to do all the time. She just needed to be heard. Just wanted to let her words linger openly so she could work through her pain.

"I worry about how he will deal with the trauma later in life. Kids bounce back. I know this. Better than adults. But he…you know this about him…he feels too deeply. This world will break his heart N'Jobu. People like that suffer more than most."

N'Jobu continued to listen as he held her hand.

"I worry about him. I told Dr. Davis this. I worry that he has inherited my pain. I pray and pray that he can be more like you, like…if I could take the worst aspects of myself and remove that from his DNA—"

"Stop."

N'Jobu's eyes were watery. He stroked her face.

"I don't want you thinking like this. I don't want you to carry this in your heart. Take parts of you out of him? He wouldn't be who he is without those parts of you. I know I'm supposed to let you feel what you feel, but my son…our son? He is perfect. He is his own person. That is an Udaku Prince out there and you make him perfect. Understand?"

"I want to believe you, I might believe you if…."

"If what?"

"If you would take us to Wakanda. It has to be safer and better there. You heard what Rolita told you at dinner. It's bad out here. You heard about Walter's science project. Fuck is that? Fuck kind of world are we living in. How can we protect Erik? What if something happens to him? What if something happens to us? Who would take care of him? Who would be capable of caring for a child like ours? Huh? Tell me."

"Babe—"

"Why won't you take us away from here? My baby is a Prince. He deserves to live in a world without fear, or where his best friend doesn't make bulletproof t-shirts for his peers. Don't you want him to have the life you had growing up?"

N'Jobu pulled her in with a tight hug when the tears really started flowing down her face. She was so tired.

"My love, don't cry, please…don't cry…"

It was the same quiet fight they had over the years. His refusal to take them home.

They weren't welcome. She knew this. Deep down they were not wanted in his world, and yet it was the only one that could save them. And she didn't understand why he prevented them from contact. Not even a visit. Their son was learning Wakandan. Memorized their alphabet. Practiced writing his name, even practiced a little speech he wanted to give in front of his royal grandparents when they would meet. Even had a gift he made for his cousin Prince T'Challa, a little necklace that would hold secret-coded messages between them.

And yet…

Here they sat with her crying about it once more.

They left the bedroom and joined the rest of the family to eat pound cake and watch Wheel of Fortune, everyone shouting at the tv their guess's at the puzzles. Neveah and Erik giggled like crazy whenever her father Dante guessed words that clearly were made up to make them laugh.

Once they returned home, Erik put away his robot, and she and N'Jobu dressed for bed. They allowed Erik to lounge in bed with them until it became way past his bedtime. She caught that mood from N'Jobu that he wanted to make love, but Erik kept prolonging his stay in their bed by negotiating for extra time with them. They allowed him to watch another half hour of the SyFy channel until he was knocked out and snoring with his head resting on Califia's stomach.

"Hey, buddy, time to wake up," N'Jobu said nudging Eric gently on the shoulder.

"Thirty more minutes," Erik whispered, his eyes wide as if he hadn't been snoring a minute ago.

"So you can sleep again? Go to sleep in your room. I need some Mommy time," N'Jobu said. He started pushing Erik away from Califia.

"Mom!" Erik whined pushing N'Jobu's hands away and trying to stay on her stomach.

"It's two in the morning, JaJa," Califia said stroking his braids.

"Then I should be able to stay since the sun will be up in five hours."

"If you don't get," N'Jobu said pulling on one of Erik's braids.

"Ow, Baba! I know why you really want me gone…you wanna kiss Mom and do the nasty!"

"Boy!" Califia said, a shocked expression on her face as she play slapped his arm.

"Yes, now get," N'Jobu said.

"I can't believe that came out of your mouth," Califia said.

"Why are you being embarrassed?" Erik teased.

"Time for you to get out of grown folks business," Califia said lifting him off of her stomach.

Erik finally rolled over and stood from their bed.

"Y'all some haters, man, for real," he said.

His dimples melted her.

"Who is this child? Where is my sweet JaJa?" she said.

Erik leaned back over the bed and kissed her cheek.

"Night Mom," he said.

"Night, Baby. Sleep well," she answered.

Erik gave his father a sly look as he sauntered out of their room backward.

"I'll just close this so I can get some rest," he said as he grabbed their doorknob and shut it behind him.

"Okay, maybe we should take some of your DNA out of him," N'Jobu said as he wiggled out of his pajama bottoms.

"That was all you, nigga," she said staring as he pulled his t-shirt over his head.

He tugged on her nightgown and she brushed his hands away.

"We can't do it now," she said glancing at the bedroom door.

"Why not?'

"Because he knows that's what we're doing—"

"I don't care, just put the pillow over your mouth," he said pulling the bed covers back and raising up her gown to her hips. She widened her legs and allowed him to lick her vulva slowly, but then she felt self-conscious. Kept glancing at their bedroom door making her stomach tense.

"I can't, not yet," she whispered.

"Babe, stop being silly. I want to make you feel good after a tough day…shit…pussy wet already."

His tongue rested just under her clit as her ring poked out from the engorgement of the slick bud. He gave light pulses there and her legs shot up, her thighs falling open.

"Get the lube," he said stroking his dick.

Reaching into her drawer she pulled out cherry flavored lube. She coated her vulva and opened her wet inner lips for him.

Tongue darting in and out and smearing his lips with her arousal, Califia held N'Jobu's head.

"Let's just do a quickie," she said.

"Quickie, longie, I just need to be in my pussy," he said shifting his body to line up with hers. He inserted his erection and she gasped out loud.

"I'm about to fuck you real good," he hissed in her ear.

Califia stuffed her left hand over her mouth as her right arm held his shoulder in a death grip.

"God, baybee—"

"Mmmmm—"

"Wait, not so hard, the headboard is banging against the wall—"

"Fuck that wall—"

"The noise—"

N'Jobu lifted up and watched his dick slide into her.

They had been working and caring for Nana Jean and Erik so much that it had been a couple of weeks since they had last had sex. And this quickie was just what they needed. If N'Jobu didn't waste any time kissing her, she knew he was desperate to get in her stuff. He couldn't go very long without some sexual contact with her.

"Look at your dick, Jobu," she encouraged, his face so intent on watching her pussy grip his length. His dick was shiny, his dark coloring magnificent. She felt sorry for people who couldn't have Black dick like this filling them up. He was ready to split her in two. She needed this. Needed him. Needed to get her mind off of her troubles.

He pulled out and positioned himself on his side behind her. His hands gripped her breasts but her gown kept slipping down.

"Take it off," he said and she removed it over her head and tossed it on the side.

White light under the door.

Erik was still up.

Califia dropped her head to one of her pillows and bit into it. She could hear how gushy her pussy was, could hear N'Jobu trying his best to keep his voice down but to no avail.

"Damn…damn…," N'Jobu grunted, his hands tightening around her breasts.

"Yes, baby."

"I missed this pussy, girl. We gotta stop playing and make time for us…oh shit…"

"Jobu—"

"Where you want it, baby? I'm ready to cum…oh…Califia…where you want this nut?"

"In my mouth," she said.

"Okay…okay….," he panted.

He kept stroking his dick in her pussy, hitting the side of her walls hard.

His pace picked up, and for a second she thought he would cum inside her because he didn't seem willing to leave her hot folds.

"Turn around!" he shouted.

Yanking out of her, he stroked his thickness as she turned around and lowered her face to his cock.

"Open your mouth…oh shit…baby open your mouth!"

Mouth Open. Tongue out.

N'Jobu slapped his dick on her tongue, his eyes swimming with an all-consuming carnality. Her own fingers plucked at her clit and when his release splashed all in her mouth, she gulped his cum down as her sugar walls clenched from an intense orgasm.

She swallowed everything he gave her, and he spent some time licking between her legs again and giving her another orgasm.

She was about to enjoy the third orgasm from his mouth when a brilliant blue light spilled under their bedroom door.

"N'Jobu!" she cried out.

He turned his head and saw the brilliant fluorescent blue. His eyes shifted in a way she had never seen before.

He leaped up and put on his pajama bottoms. She threw her gown back on and followed him out of their bedroom.

Erik's bedroom door was open, the dazzling blue array coming from there.

"Erik!" N'Jobu shouted.

Their son stood in the middle of his bedroom. N'Jobu's Wakandan beads were on his wrist, the blue light bleeding out from it.

"Baba!"

Erik tried pressing down on a bead.

"Don't do anything else!" N'Jobu said.

But it was too late.

Erik twisted one of the beads and the brilliant blue light filled the entire room and a large holographic image floated above Erik's wrist.

A street scene.

People walking on elevated sidewalks.

Space ships flying in the air.

Black people dressed in ways they had never seen before.

"N'Jobu, what is this? What is that?" she whispered with awe in her voice.

Erik's eyes studied the images and he took his free hand and stuck it inside the field of blue light. It expanded and different color-rich scenes played like a series of split screens spinning in a circle.

A cityscape.

And a futuristic structure that looked like a double palace…

"It's Wakanda," Erik said.

His fingers flicked an image up over his head. It looked like a billboard advertising a car they had never seen before in the world. The lettering was all Wakandan.

Erik's bright eyes stared at her.

"It's Baba's home!"

###

Chapter 24

Tag List”

@fd-writes @soufcakmistress @cherrystainedlipsbaby @tclaybon @thadelightfulone @allhailqueennel @bartierbakarimobisson @cpwtwot @shookmcgookqueen @yoyolovesbucky @raysunshine78 @the-illllest @terrablaze514 @l-auteuse @amirra88 @jimizwidow @janelledarling @chaneajoyyy @sweetestdream92 @purple-apricots @blackpinup22 @hennessystevens-udaku @scrumptiouslytenaciouscrusade @bugngiz @stariamrry @honeytoffee

#black boys bloom thorns first volume 2#n'jobu#n'jadaka#erik stevens#black panther fanfiction#black panther smut#killmonger#when killmonger was a boy

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I Learned When I Rented My Parents’ Former Home as an Airbnb

They’d tried to escape the future by building a home off the grid. But the future found them anyway.

— By Thad Russell

— The Atlantic | August 29, 2021

September 2005 (All photos by Thad Russell)

About the author: Thad Russell is a photographer who lives with his wife and two children in Providence, Rhode Island, and teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Two summers ago, my siblings and I found my late parents’ former house in northern Vermont listed on Airbnb. Once we got over our shock—“Wait! That’s our house!”—we immediately made reservations to rent it for a family vacation. The new owners had known my parents and generously waived our rental fee upon realizing who we were. The online description—“rustic retreat”—brought back memories of countless family gatherings of summers past: taking long walks, swimming in the lake, eating local corn and blueberry pie. I remembered hanging out together on the deck that extended into my parents’ gentle, south-sloping meadow like a pier, appreciating the peaceful view of hay fields, spruce trees, mountains, and an ever-changing sky.

I looked forward to the reunion for months. And yet, as I drove with my wife and young children along winding mountain roads that I knew by heart, I was surprised by the emotions stirring inside me. I began to realize something that should have been obvious. This special, idealized place that I was so excited to return to wasn’t a repository of just happy memories, but of difficult ones too. My parents had been concerned about the political and environmental trends in America. Their place in Vermont was meant to be a political statement in the form of a modern-day frontier house—hand-built, off the grid, and completely DIY. In other words, it was very difficult to live in and maintain. Now that many of their worries about climate change and political unrest have become reality, I understand the prescience of their vision and the virtues of the life they were designing. I also realized something even more important, however, when I rented their home as an Airbnb: No matter how hard you try to escape the future, the future will find you anyway.

May 2015

In the 1990s, my parents sold our family home in suburban Boston and moved to a virgin piece of pasture in Vermont’s rural and remote Northeast Kingdom in order to build a house—and a life—from scratch. They wanted to slow down, to live simply and more in concert with nature and its seasonal rhythms. My siblings, their spouses, and I not only supported this new chapter but were actively involved every step of the way. Though we all had careers, homes, and lives in other places, we would parachute in every August to help pour a foundation, build a timber frame, side a barn, or mow a field. This collective labor gave us a sense of investment in the property—“sweat equity”—and senses of accomplishment, pride, and joy in its growing compound of rough-hewn structures. We finished the “little house” (which is actually tiny) in time for my sister’s wedding one August, and we finished the “big house” (which is actually quite little) in time for my brother’s wedding six years (to the day) later.

This property was the realization of a long-held dream. My father was an MIT-trained architect and builder with his own brand of rugged modernism. His houses were shrines to their specific surroundings, made out of locally sourced wood, stone, and glass. After spending a lifetime building homes for others, he wanted to finally build one for himself and his family.

But he wasn’t trying to construct a well-appointed vacation home, and my parents weren’t hoping to retire comfortably to the country. They were hoping that their modest compound could be a refuge, a place separate and protected from the evil and disease of the modern world, a place to which we could all retreat when the long-prophesied and always-imminent economic and ecological disaster of Man’s own making finally came home to roost. With its solar panels, windmill, vegetable garden, root cellar, and well, it was designed to be a self-sufficient place apart, a lifeboat of sorts.

Though my parents’ organic, less-is-more lifestyle was supposed to be simple, it was never easy. Their life was intentional and incredibly labor-intensive, marked by hard work and discomfort. Their property became an unrelenting taskmaster. Many projects never got completed. Some just didn’t work. The sun didn’t always shine. The wind didn’t always blow. Batteries failed. The bespoke, high-efficiency refrigerator didn’t actually keep food cold. The well was contaminated with surface water from a nearby cow pasture and never produced reliably potable water. My parents’ self-imposed restrictions on energy usage—my father designed an aggressively frugal system that used only one-20th the amount of electricity of an average American family—seemed arbitrary, impossibly difficult, and puritanical; a dishwasher or clothes dryer was out of the question.

They—and we—argued a lot about how they lived, and the choices they had made. I thought theirs should be a model home, an equally attractive, non-fossil-fuel alternative that others could easily emulate so that we could collectively save the planet. My father thought it should be more of a laboratory that embraced cutting-edge experimentation, took risks, and courted failure. He thought it should be difficult by design so as to attract only zealots, purists, and true believers.

August 2019; May 2015

My mother sometimes complained about the ways the house didn’t work and she felt burdened by the endless list of domestic chores that seemed to fall disproportionately on her, but she nonetheless embraced this new life with passion and conviction. Why? For starters, she loved my dad and believed in his genius and vision. She was also a longtime political and environmental activist. Lastly, thanks to her strong Protestant work ethic and her progressive Christian faith, she always believed that wisdom and virtue came from labor, sacrifice, and struggle. I think she loved this new, difficult chapter of her life, not despite the challenges but because of them. It made her feel more alive, more connected to her husband and to herself, her planet, and her God.

One particularly hot and restless night in the summer of 2003, while sleeping in my parents’ barn, I awoke with a scary premonition: Things here were not going to end well. My parents were not going to live forever, and I had a feeling that their path ahead might be far more difficult and treacherous than any of us were prepared for. A few months later, my mother was diagnosed with cancer. The next three years were consumed by her illness, including her weekly drives across the state for radiation and chemotherapy. The August after she died, we had a memorial service for her under a tent in the exact same spot in the meadow where my sister and brother had each been married years earlier.

My father lived for eight more years, but his heart was never the same. First it was broken, and then, eventually, it began to fail. What he could do—and wanted to do—shrank considerably. For the first time ever, he stopped planting a garden. “What’s the point?” he said. Mail piled up. Bills went unpaid. Phone calls went unanswered. Dirt and dust collected everywhere. Necessary and long-overdue house maintenance was put off indefinitely. He would spend hours and days sitting and staring, at the clouds in the summer and at the wood fire in the winter. The house he built with his own hands became a waiting room, a purgatory clad in native spruce. One day in November 2013, he couldn’t get out of bed. I was visiting at the time, having driven north from Rhode Island after receiving a call from a concerned neighbor. I remember the ambulance in the front yard, parked on top of my mother’s perennial garden and EMTs dressed in Carhartt overalls taking my dad away on a gurney.

My father died the following August; two months later, we mixed my parents’ ashes and spread them in the meadow as friends and family looked on.

After my father’s death, my siblings and I debated whether to keep the Vermont property. I always thought we would. But the more we talked, the more I realized it was going to be financially and logistically impossible. The buildings were not in great shape. Managing their restoration and preservation was going to be complicated and expensive, and was going to take time, energy, and money that none of us had. Moreover, the property was hard to reach. We also realized that we weren’t simply inheriting a house or a piece of land, but a way of life, a philosophy, a set of values that we all respected but didn’t fully subscribe to. No, we all decided, it wasn’t right—or perhaps the right time—for any of us. With heavy hearts, we decided to let it go.

October 2005

Fast-forward to the summer before last, five years after my father’s death: We were returning to our family homestead, but this time as Airbnb guests. As we approached the house from the long dirt driveway, everything was at once familiar and surprisingly different. I instantly noticed all of the improvements: a new metal roof, new wood siding, and a completely rebuilt breezeway connecting the two houses; lush new landscaping featuring exotic flora and brilliant orange poppies that reminded me of California; a new well, professionally dug, with (I learned later) sweet, cold—and E. coli–free—artesian water.

The interior was stunning and immaculate. Everything seemed carefully and painstakingly finished, no more exposed electrical wires or pipes. A new floor was made out of spotted maple, and a fresh coat of satin varnish covered all the wood surfaces. The decor was modern and sparse—chairs made out of soft Italian leather and German stainless-steel appliances, including a dishwasher and a dryer. To my eyes, the house had never looked better and had never been more beautiful, more finished, more realized. The future looked good on this house. My appreciation was complicated, however, tinged with envy and regret. Why couldn’t this beautifully designed and now brilliantly realized house still be ours?

I also couldn’t help but notice what was no longer there: the vegetable garden; the windmill; the woodshed, wood stoves, and Finnish oven; the solar electric system. The house is now on the grid and comfortably heated with gas, its massive propane storage tank elegantly concealed underground. Sure, the house still looks groovy, but it’s now hippie house lite, like tie-dyes and distressed bell-bottoms one buys at the Gap. It has the counterculture aesthetic but all the dirt, difficulty, and rebelliousness have been removed. As my father might say, “What’s the point?”

But I have come to realize that the new owners have actually been the perfect stewards of our old property. Their careful and systematic restoration has removed the dust, decay, and dysfunction while preserving the essential design and rustic charm. I also realize that it is their house now, not ours, and maybe that’s a good thing. The burden of the property, its deferred maintenance and challenging memories, was too much, and is too much for me still.

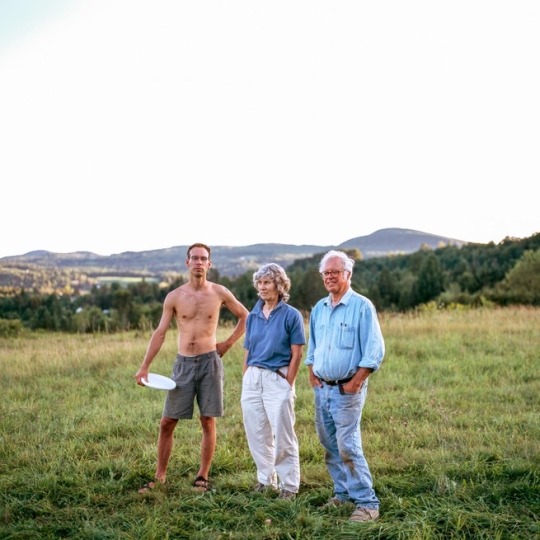

The author’s brother, mother, and father. August 2001

Now, two years—and a world of difference—later, I find myself thinking about that piece of pasture in northern Vermont and my family’s 25-year adventure there. We are living through such scary and turbulent times. We are simultaneously in the throes of a resurgent global pandemic and a rapidly emerging climate crisis. Viral death tolls, huge heat domes, megadroughts, and 1,000-year floods mark our daily news. As I write this, dozens of massive western fires burn uncontained, their smoke turning even eastern skies an eerie and unhealthy shade of ocher. The world is changing in ways that many people find hard to believe and hard to endure, but that my parents essentially anticipated. They were preparing for this future; they saw it coming and tried so hard to protect their family—and themselves—from the pain and suffering that they feared it might bring. Now that that future is here, I realize we can’t really escape it. The future always catches up with us, and no matter where we are or where we go, we are all survivalists now.

— Thad Russell is a photographer who lives with his wife and two children in Providence, Rhode Island, and teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design.

0 notes

Text

W in Art: Hoi-Fei Mok ‘10 (@alifeofgreen)

Cover Image by Lydia Yamaguchi

Hoi-Fei Mok is our fearless leader here at WU but they are also an artist, activist and environmental scientist. Based in the Bay Area, Fei recently completed a fellowship with the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts as part of the cohort addressing the question “What does EQUITY look like?” We recently sat down to talk about the arts, sciences, and the YBCA fellowship experience.

What is your “origin story”? How did you fall in love with the arts? (and sciences?)

I’ve been a creative person since I was young - drawing, painting, playing the violin. I never expected to take it far because I was always told it wouldn’t make a good career. At Wellesley, I became super focused on my schoolwork and pretty much stopped anything creative except orchestra. Even then, it felt like doing things out of habit rather than for the joy of it. After graduating, I really wanted to go back to art. I picked up the guitar and bought some paints, but wasn’t confident in how to jump back in. A writer friend of mine told me to just do it, sketch something out even if it doesn’t look good, and made me set a goal to have two pieces ready in time for his book reading in a few month’s time. That really helped me get back into the groove of things. Slowly I got away from the thinking that art had to look portfolio ready or that my music had to be perfect, and I started doing it for my own self-care and joy. Eventually as I got more radical and involved in activism, my art also became a medium to talk about social justice and I joined community art projects.

My route to science came about through my environmentalism. I majored in biochemistry thinking I was going to go to veterinary school (to save the animals!), but I realized in hindsight (the summer before senior year, hah) that this came about from my interest in conservation and the environment. I ended up doing some ecological research after graduation and ended up getting my PhD in environmental science, focusing on wastewater reuse for agricultural irrigation. And now I work in climate change policy. Looking back, science set a good foundation for understanding the environment and climate change, but I wouldn’t say I fell in love with science so much as realized that I was good with data. I am hugely passionate about addressing climate change and while it is very useful to have a science background, climate change is not just a technical problem, it requires a strong social, political, and economic understanding as well. So I’m still in the process of learning all of that.

How has your background in science influenced your art, and vice versa?

I haven’t gotten as much crossover as I would like (or generally enough time/capacity for doing art)! There have been a few climate related pieces that I’ve done, like this recent street art installation about bee colony collapse and the seed connection in my art fellowship project below. I love the pieces that incorporate climate data directly, like Jill Pelto’s paintings, Natalie Miebach’s musical sculptures, or this string quartet of rising temperatures, and all of the light installations by Luzinterruptus are brilliant for bringing in so many environmental themes, upcycling, and public education. I’m really interested in exploring installations more, so as soon as I get the right opportunity, that’ll be the next thing I’m working on.

What is the story of this fellowship? (selection/application)

The Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) is a unique art institution in San Francisco. They work from the premise that art and culture drive social change, so many of their projects have a social justice bent. Their Fellows program came out of their annual YBCA 100 Summit in 2015. During this summit, people crowdsourced hundreds of different questions that drive and inspire community transformation. These questions were distilled down to three themes: 1) can we design freedom?, 2) what does equity look like?, and 3) why citizenship? Then three cohorts of 30 people - artists, activists, policymakers, writers, educators, and more - were selected by essay to “engage in a yearlong process of inquiry, dialogue, and project generation”. I applied for the equity cohort and (much to my surprise) was accepted.

Can you give us a brief overview of the final project that you ultimately presented?

We had a couple of group collaborations. Our cohort came up with an equity statement which came out of this beautiful collective exercise of brainstorming what equity looks like to each of us. Malcolm Gin analyzed the most frequent words and Martin K. White pulled them together into a free flowing poem. It may not make a ton of sense to the layperson reading it, but the collective process that created the piece represents to me one of the truest forms of equity and inclusion, and reminds me that the process is as important as the outcome itself.

We also wrote up a framework for creating equitable community art projects, which was shared on WU a few months ago. We created the guide for those looking to do community art projects to help them design equitable and inclusive projects that don’t take advantage of the communities they’re working in or help to gentrify the neighborhood. As artists are often the first wave of gentrifiers in a neighborhood, we felt very strongly that we needed to help other artists understand how they can work with the community and raise up local voices, rather than come in to take up more space.

In addition to these group projects, we each had individual projects we were working on. My project partner, Shalini Agrawal, and I were inspired by the People’s Kitchen Collective as well as an existing collaboration YBCA had with the local elementary school, Bessie Carmichael. Our final project, Food Equity and Cultural Memory: A Public Feast, was done in collaboration with rising first graders from Bessie Carmichael and artist E. Oscar Maynard. During the past school year, the students collected oral and cultural histories of family recipes that resulted in the recipe cards by Oscar. Using the recipes as a point of inspiration, we designed a public meal for attendees of YBCA Public Square. In feeding the public, this project highlights the issue of food access and insecurity in the neighborhood as well as the available cultural resources and memory in the form of recipes passed down from generations. By providing seeds to the feast participants, we reconnected the ideas of growing and cooking one’s own food to resilience, the earth, and self-sustainability. The students were centered as featured artists and like the seeds, they are the rising stewards of resilience for the community.

The projects were all presented at an one day public square exhibition at the YBCA. My first time presenting work at a high profile art museum, so pretty cool!

The theme of this year’s fellowship was addressing equity. How did you approach this theme? (on your own and collaboratively?)

The topic of equity is really wide. We could start by talking about what it DOESN’T look like (racism, poverty, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, Islamphobia, misogyny etc) and that in itself is already a complex topic because of all the intersections. But finding examples of what equity DOES look like is much harder, especially in thinking about how to bring it to fruition. We spent several sessions workshopping some ideas on this and I don’t think we came close to even scratching the surface on the question.

One of the interesting points we brought up was whether equity is some horizon that we never actually reach because true equity is impossible and we spend our entire lives working towards it and maybe that’s the point that we’re struggling in process all the time. Darkness, pain, and trouble was one of the recurring themes in our discussion and needing to move through it to self heal and realize the love.

We spoke a lot about the public square and the intention behind it. Many of us thought that an one-day event wouldn’t be enough to really achieve everything we wanted (change the way community arts is done, catalyze some of the momentum from the post-election political revitalization), but we recognized it as the beginning rather than the end-all. That being said though, we wanted it to be as equitable and inclusive as possible, which included making it accessible to people who wouldn’t normally feel invited/comfortable to art museums. One of the things we fought for and won was provision of a higher number of complimentary tickets and promotion of YBCA’s pay-what-you-can membership offering. My project partner and I intentionally set our project outside so that we could reach people who weren’t otherwise going to go inside the museum. One of my highlights was in fact talking with an Iranian elder who wandered over from the Yerba Buena Gardens and sharing some fava bean salad with him, which made him remember Tehran.

What was your creative process for this project? How long did it take and how much of the work was done either solely/with the project team vs input from others (not actually working on the project) along the way?

The fellowship was structured initially for monthly meetings over the course of a year. YBCA organized guest lecturers to showcase different examples of what equity could look like and facilitated some discussion during the meetings. But we didn’t get many opportunities in the beginning to talk with each other about what we thought equity looked like. A few of us started organizing outside meetings a few months in to get to know each other and attend community events to get ideas. But before that could take off, the aftermath of the national elections hit and we were all in a stupor over the holidays. And then finally, six months after we started, after we had a second round of cis white dudes presenting to us (a cohort on equity of all things), we put our foot down and decided to self organize.

It was really, really hard trying to restart in the middle of the year. Not only were we trying to get to know each other, we were also trying to schedule outside meetings for 30 people, hold each other accountable, figure out what exactly we were doing as a group and as individuals, figuring out project finances, and talk about this giant topic of equity. Needless to say, it was really exhausting and frustrating, particularly when the brunt of the labor of organizing/attending the extra meetings and herding all of us cats was done by the women/genderqueer folx in the group. And then after we had group meetings, we had project meetings with our project partners. Unfortunately, talking about logistics and organizing took up about 80% of our time and energy, with so little leftover to actually dive into the content.

But when we did get to connect, it was beautiful and illuminating. We had grand ideas for what the public square should be like and we knew we didn’t want it to look like a disjointed science fair with projects all over the place. We came up with the equity statement to help tie everything together and several of our projects were created with similar themes (games/play, benches as a metaphor for equity, etc). For my own project, I had approached my project partner Shalini with an idea early on in December and we kept up conversations about it, but didn’t get around to settling on a solid project until April. Meeting and working with Shalini was definitely one of the highlights of my fellowship experience. Shalini is the director of the California College of the Art’s Center for Art and Public Life and is super experienced guiding projects through, so it was really awesome to learn from her, especially the brainstorming process, which I always struggle with. It was also my first time doing production for an event like the public square, as much of my previous art is visual, so the process was quite different from what I was used to. And despite the high level of stress/frustration, it was also a good learning experience.

Looking back, is there anything that you wish you had/the team had done differently?

Some reflections from our fellowship are written up here by Katherin Canton and Trisha Barua here but “moving at the speed of trust” sums it up pretty well. Because we didn’t get the time in the beginning to build relationships with each other and talk with each other, it was so much harder when we had to self organize because we couldn’t fall back on our relationships to hold each other accountable (and show up to meetings or even fill out the doodle poll to have said meeting). One of my biggest takeaways was that in any project, you have to get a solid working relationship before you can move forward.