#Globally Local Joins Forces with DoorDash

Text

Globally Local Joins Forces with DoorDash

Globally Local Joins Forces with DoorDash

Globally Local — a rapidly expanding vegan fast-casual restaurant chain — recently joined forces with on-demand delivery platform DoorDash to deliver high-quality plant-based food straight to your doorstep. The brand is offering its entire menu, ranging from its iconic ‘Famous Burger and beloved ChickUN PreTenders to its Greek-inspired Gyros and ChickUN Souvlaki — to name a few.

The vegan brand…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Four Ways COVID-19 Has Changed App Store Optimization

The global impact of COVID-19 has radically reshaped nearly every aspect of daily life. From sheltering-in-place to social distancing, people around the world are adjusting to limited contact and removal from once commonplace activities including commuting, shopping, and gathering in public places. More than ever, the smartphone serves as a primary conduit to the outside world, supplementing areas where ordinary life still remains impossible. As a result, 2020 is already well on its way to being the biggest year in the history of mobile apps, in terms of both adoption and consumer spending.

For growing mobile companies, it is critical to adjust organic acquisition strategies to meet this unique time. As user behavior has changed, some of the most mature mobile app companies across all categories have made significant alterations to their approaches in order to keep up.

Based on Sensor Tower and Storemaven findings, here are five critical ways COVID-19 has changed App Store Optimization (ASO) in 2020.

This Sensor Tower post was created in partnership with Storemaven. To learn more about their platform, please visit their website.

Emphasizing Remote Work

One of the defining trends amid COVID-19 has been the unprecedented rise of organic installs of business and education apps in the stores, leading to a record year for both categories. Global downloads for business apps in the first half of 2020 increased by nearly 150 percent year-over-year to 1.9 billion across the App Store and Google Play, while education apps saw 42 percent Y/Y growth to reach nearly 2 billion. With more developers than ever cobbling together remote office and classroom tools, consumers are directly searching for the services they need, or are required to have by their employers and schools.

According to Sensor Tower data, searches for Zoom, Google Classroom, and Microsoft Teams have seen huge gains by traffic score growth compared to the same time period in 2019, meaning that consumers know exactly what they want and are searching for it directly. This search behavior has also contributed to all three services experiencing record downloads throughout Q1 and Q2 2020. Zoom has seen the largest increase overall, achieving record in downloads for a business app and becoming the most downloaded app globally in the second quarter.

With working from home the new reality, many app publishers have addressed this shift in their ASO messaging and strategy, positioning themselves as facilitators of remote work. These copy and image changes have addressed the new reality of remote work interactions, in order to maintain appeal during COVID-19. For example, Square reacted quickly to COVID-19 by changing the first screenshot for its Square POS app—the business operations companion to its consumer payment app—on both stores to emphasize the ease of selling online through its use.

It’s critical for apps across all categories to consider their relationship to facilitating remote interaction, especially in relation to business and education. Prioritizing access, ease, and remote interaction are strong immediate steps that can be taken to keep up with the shift in how users are searching for online tools to make the best of this time.

Focusing on Brand Awareness

While more users than ever are directly searching for what they need, changes in traffic for non-app names varied, highlighting the turbulence certain categories are experiencing as shelter-in-place and reduced contact initiative continue around the globe. More holistically, general search terms and passive browsing have declined, indicating that there is an overall lack of exploration of mobile app stores by consumers compared to the year prior.

According to Sensor Tower data, search traffic for terms such as “weather,” “maps,” and “podcast” has decreased during COVID-19, highlighting a handful of the hardest-hit categories during the pandemic as consumers are indoors and not traveling or commuting. Indeed, even as ridesharing and travel apps such as Uber or Expedia have seen light recovery in the weeks following the 200th confirmed case of COVID-19, there’s little hope that they will be able to make a full recovery to pre-pandemic levels this year.

A dive into Storemaven data shows that Browse impressions decreased by 46 to 60 percent after late February of 2020, potentially spurred by a combined decrease in passive exploration and an overall strategy by mobile companies to reduce or change user acquisition budgets and strategies in the face of uncertainty.

With the lack of browsing-driven discovery becoming an overall trend over the past several months, it’s key to focus on word-of-mouth as a valuable marketing tool in combination with organic and paid mobile search strategies. As consumers continue to search for apps by name, marketing campaigns that focus on referrals could have a unique appeal.

Staying Supportive

One of the challenges of COVID-19 is that it’s a global event—a stressful and abnormal sequence of events that has forced the world out of its known routine. It���s hard to acknowledge that things have changed without being gloomy or awkward, but it’s critical that mobile app markers take extra care when communicating with customers.

According to Storemaven, mobile developers have sought to meet the moment of COVID-19 by changing their overall tone and positioning on the App Store. Within store descriptions, images, and even update notes, companies have gone out of their way to insert supportive and encouraging messaging within their store profiles.

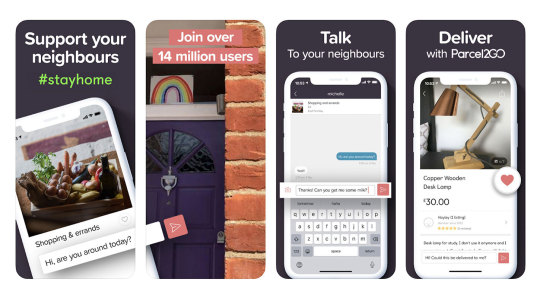

One example is Gumtree UK, the online classified advertisement website, which completely shifted its positioning focus to the community perspective of local second-hand shopping and its new delivery product feature. The app also highlighted the ability to get groceries delivered and chat with your neighbors, in order to make the best of living with awareness of COVID-19.

Companies worldwide have considered it beneficial to identify particular pain points and struggles related to COVID-19 in their user base, and connect with them on a more personal level. Through showing a more authentic side—one openly acknowledging the unique challenges of the past few months—apps are able to build better brand trust and connect with their customers on a deeper level.

Highlighting Contact-Free Experiences for Essential Services

In addition to acknowledging the uniqueness of our lives amid COVID-19, many apps have taken to highlighting minimal contact as a selling point for their services. According to research by Storemaven, when social-distancing became the present need, companies increasingly changed their messaging and creatives to showcase their safety.

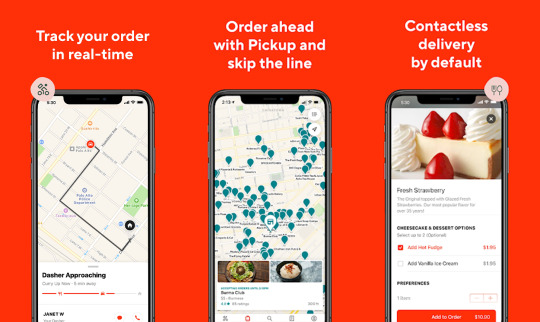

For example, food delivery and takeout service Doordash added “contactless delivery by default” messaging directly on its app’s store page. By also altering the the first few seconds of its page video and third screenshot on the page, Doordash highlighted the safety measures Dashers would be taking to ensure food was delivered safely.

COVID-19 has not been ideal for food delivery apps, with minimal boosts in interest countered by closures of area restaurants for the sake of public health and safety, as well as the overall decline of food delivery for the sake of saving money. However, DoorDash in particular has seen a slight improvement: According to Sensor Tower Data, after three straight quarters of declining installs between Q2 and Q4 2019 in the United States, DoorDash saw record downloads in Q2 2020.

Where applicable, highlighting the safety and precautionary measures taken during COVID-19 is a great way to deliver peace of mind and convert interest to installs. Although needs may fluctuate in this ever-changing time, being open and transparent about public health is another great way to build lasting trust.

Rolling With Changes

Although we’re months into the COVID-19 pandemic, circumstances continue to change day-to-day. While some countries appear to be in more prolonged and hopeful periods of recovery, others, such as the U.S., are still struggling to adjust to the lasting effects of managing a public health crisis. It’s important to remain mindful that authenticity and utility will continue to stay at the forefront of consumers’ minds for the foreseeable future, so leading communications with empathy will be one of the most valuable decisions any app publisher can make.

About Storemaven

Founded in 2015, Storemaven creates innovative, industry-first mobile growth technologies and is the world leader in Mobile Growth and App Store Optimization (ASO) specifically. Storemaven helps top mobile companies like Facebook, Uber, Zynga, and Warner Brothers optimize their marketing performance in the app stores, by giving them access to a treasure trove of data and unmatched domain expertise on how the app stores work. For more information, visit www.storemaven.com

About Our Guest Co-Author, Jonathan Fishman

Jonathan is Storemaven’s Director of Marketing. Before joining Storemaven, he spent over 10 years commanding tanks, working on Wall Street, consulting high-growth companies, and exploring Black Rock City. In his spare time, he likes building things from wood, writing, and listening to Frank Zappa.

Four Ways COVID-19 Has Changed App Store Optimization published first on https://spyadvice.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

How Coronavirus Could Change the Way You Get Your Favorite Craft Beer

Mihai_Andritoiu/Shutterstock

Competition is fierce for cans, labels, and customers as breweries rush to package their beer for home drinking

It’s been a rough couple of months for craft beer. Like the coffee and wine industries, the entire beer ecosystem was upended as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered breweries, closed bars, and scared people away from beer shops. “March was kind of a bloodbath, financially speaking,” says Josh Stylman, co-founder of Threes Brewing in Brooklyn. “If you had asked me two months ago, I would have said I don’t know if our company is going to make it.” And that’s coming from a well-known, award-winning brewery in a huge market.

The pandemic has forced some breweries to close, and while COVID-19 has certainly pummeled the beer business, recent data from the Brewers Association shows many brewers are optimistic about their chances of survival. Operations that remained open the last few months found new ways to serve customers; others are now reopening alongside bars in some states.

Still, the crisis has forced breweries to completely reimagine operations. While bars and taprooms were forced to close, demand for beer remained through the darkest hours of lockdowns (plenty of socially distanced people still want to drink at home). Instead, the major disruptions were in distribution. According to Bart Watson of the Brewers Association, before the pandemic, 10 percent of an average American brewery’s output went into kegs, and that beer would go on to be sold on draft at bars, restaurants, and breweries’ own taprooms. For craft brewers, that number was much higher, nearly 40 percent, and they especially relied on in-house taprooms and brewpubs.

The rest went into off-premise sales like cans and bottles. But as on-premise sales dried up completely, brewers had to repackage their beer any way they could. “As soon as we closed, we decided any drop of liquid that can go in a can needs to go in a can,” Stylman says. While Threes had already been canning its beer for a few years, the shift required recalculating the brewery’s entire operation, costing time and money. “We just ordered a million different kinds of boxes to find the best one. We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

“We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

Some breweries that were forced to pivot to repacking use growlers or crowlers, relatively affordable entries into packaging for many small breweries. Crowler machines or other manual can seamers only cost a few thousand dollars, but they’re labor intensive, they’re usually filled and sold directly from taprooms (not at retail), and their DIY packaging doesn’t provide the best shelf life. Other brewers that never canned before have partnered with mobile canning companies like Codi Manufacturing or Mobile Canning, some of which have provided discounts or donated labor to help the struggling industry keep afloat. A few brewers, unable to redirect their entire stock into packages, had to dump beer that couldn’t be moved.

Pivoting may be more difficult depending on how a brewery’s business was spread across sales channels before the pandemic. Brewmaster Ben Edmunds of Breakside Brewery in Portland, Oregon, for instance, says pre-COVID-19, the brewery put 70 percent of its beer in kegs. Shifting to packaging has “softened the blow, but hasn’t allowed us to grow back to where we were,” he says. “We’re operating at about 50 percent.”

Even as alarmist headlines declare Americans are drinking shocking amounts of alcohol at home, for many breweries, off-premise sales can’t make up for the loss of on-premise sales. Part of the trouble is that once the beer is in cans, breweries still have to find ways to get their products into drinkers’ hands.

Greater placement in mainstream grocery chains may seem like an attractive way to reach customers, but it’s an uphill battle. Chains typically refresh their lineups twice a year, in spring and fall. “Even though the total volume of packaged beer is up, the market for packaged beer has actually tightened. When there are such good sales going through grocery stores, they’re loath to add new items. They don’t need to,” Edmunds explains. “If you’re in there and you have those chain placements, things are going gangbuster right now. But if you don’t, it’s hard to crack into it.”

Luckily for small operations like Denver’s Lady Justice Brewing, a wave of localism has risen to support community brewers that may not have the ability (or interest) to access widespread distribution. Kate Power, Betsy Lay, and Jen Cuesta used a fundraiser to launch the one-barrel brewery as a philanthropic project in 2016. It was one of, if not the first to introduce membership beer sales to Colorado through its Community-Supported Beer (CSB) program. Customers paid ahead of time to provide funds to brew the beer, and all profits went to local organizations benefiting women and girls.

The trio grew into a new taproom in March, but when Denver locked down, they revived the CSB concept and immediately saw record demand. “People feel good when they buy our beer because they know it’s going to help their own communities. It’s a way to help people stay connected,” Lay says. “The neighborhood has really been investing in us.”

Beer delivery has also seen a huge jump, with 30.5 percent more breweries saying they are delivering beer locally, 3.8 percent newly partnering with third-party delivery platforms, and 4.8 percent adding direct-to-consumer shipping, according to the Brewers Association. Loosened alcohol delivery laws have allowed brewers to list products on services like Doordash and UberEats. Stylman, who has seen how restaurants have struggled with those platforms, says Threes launched direct-to-consumer delivery in-house in order to avoid fees, rehire furloughed taproom workers, and offer subscriptions for cases of its flagship beers.

Online beer retailer Tavour has also seen a bump in business. Once mostly a platform for craft geeks to drop big money on rare brews, lately Tavour has welcomed more casual customers who typically shop at brick-and-mortar retail. The online market usually adds seven new breweries a month, but 47 have joined since March. Megan Birch, director of marketing for Tavour, says about half of those entirely self-distributed before partnering with the service, and a handful only sold through their own taprooms. Big names like Mikkeller and cult brands like Parish Brewing have listed beers that may have never appeared on such a site under ordinary circumstances. “You’re definitely seeing breweries that never wanted to work with us because they never really needed to,” Birch says.

Even as brewers adapt to the new normal, new challenges appear all the time. In April, brewers worried about a shortage of CO2, a byproduct of ethanol production used to carbonate beer. Demand for ethanol, which is mixed with gasoline, dropped during the pandemic, and plants halted production. While plummeting ethanol sales didn’t end up harming breweries as much as expected, the episode illustrated how supply remains extremely vulnerable to global developments. More recently, with nearly every brewery transitioning to packaged beer, more pressure has fallen on supply chains for raw materials. “All of the glass suppliers, all of the label suppliers, all of the can suppliers in particular have seen increased lead time,” Edmunds says.

Looking ahead, as the nation officially experiences a recession, Edmunds expects financially cautious drinkers may dampen the explosive growth the craft industry has seen over the last decade, both in beer prices and product availability. “Five years ago the $16 six-pack was the outlier. Now it’s routine to see beers go for $20 or even $25 for a four-pack,” he says. “I don’t think we’ll see beer prices fall like crazy for your average six-pack, but more for that super-premium tier.” He also expects the market to curb “SKUmaggedon,” the proliferation of brands and niche releases. Both at retail and bars, Edmunds says, owners may eschew the constant churn of new products for surefire sellers. “Wholesalers but also retailers have wanted to have a reset on that, to go back to a more controlled method for getting beer out,” he adds.

The pandemic has also united breweries across regions to call for a reset on another aspect of distribution: local regulations that have limited or complicated alcohol delivery. The pandemic has inspired legislators in some areas to relax those rules temporarily, but changes could become permanent if brewers get their way.

“The temporary orders and the demonstrated ability of state regulators to enforce them have … shown that beer to go can be done responsibly,” Brewers Association president and CEO Bob Pease says. Consumer caution could choke on-premise sales for years to come; Pease emphasizes that responsible, flexible distribution will help save countless businesses and jobs. Long-term policy changes could provide a silver lining to the economic crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic may last months or years, but it has also permanently changed how some brewers do business. “I was talking to another brewer who said, this is great, we’re selling stuff on our website, but we can’t wait until it goes back to the way things were. That is decidedly not our approach,” Stylman says. Digital sales and delivery will remain “connective tissue” for the brewery long into recovery.

That may be wise, as the pandemic could affect consumer demand for a long time to come. “There are a lot of people who have really gotten used to staying at home,” Birch says, “and when everything does open up, they’re not really going to want to go out. It’s so much easier to just get beer delivered to their house.”

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2N5sxDb

https://ift.tt/2N1Z7ps

Mihai_Andritoiu/Shutterstock

Competition is fierce for cans, labels, and customers as breweries rush to package their beer for home drinking

It’s been a rough couple of months for craft beer. Like the coffee and wine industries, the entire beer ecosystem was upended as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered breweries, closed bars, and scared people away from beer shops. “March was kind of a bloodbath, financially speaking,” says Josh Stylman, co-founder of Threes Brewing in Brooklyn. “If you had asked me two months ago, I would have said I don’t know if our company is going to make it.” And that’s coming from a well-known, award-winning brewery in a huge market.

The pandemic has forced some breweries to close, and while COVID-19 has certainly pummeled the beer business, recent data from the Brewers Association shows many brewers are optimistic about their chances of survival. Operations that remained open the last few months found new ways to serve customers; others are now reopening alongside bars in some states.

Still, the crisis has forced breweries to completely reimagine operations. While bars and taprooms were forced to close, demand for beer remained through the darkest hours of lockdowns (plenty of socially distanced people still want to drink at home). Instead, the major disruptions were in distribution. According to Bart Watson of the Brewers Association, before the pandemic, 10 percent of an average American brewery’s output went into kegs, and that beer would go on to be sold on draft at bars, restaurants, and breweries’ own taprooms. For craft brewers, that number was much higher, nearly 40 percent, and they especially relied on in-house taprooms and brewpubs.

The rest went into off-premise sales like cans and bottles. But as on-premise sales dried up completely, brewers had to repackage their beer any way they could. “As soon as we closed, we decided any drop of liquid that can go in a can needs to go in a can,” Stylman says. While Threes had already been canning its beer for a few years, the shift required recalculating the brewery’s entire operation, costing time and money. “We just ordered a million different kinds of boxes to find the best one. We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

“We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

Some breweries that were forced to pivot to repacking use growlers or crowlers, relatively affordable entries into packaging for many small breweries. Crowler machines or other manual can seamers only cost a few thousand dollars, but they’re labor intensive, they’re usually filled and sold directly from taprooms (not at retail), and their DIY packaging doesn’t provide the best shelf life. Other brewers that never canned before have partnered with mobile canning companies like Codi Manufacturing or Mobile Canning, some of which have provided discounts or donated labor to help the struggling industry keep afloat. A few brewers, unable to redirect their entire stock into packages, had to dump beer that couldn’t be moved.

Pivoting may be more difficult depending on how a brewery’s business was spread across sales channels before the pandemic. Brewmaster Ben Edmunds of Breakside Brewery in Portland, Oregon, for instance, says pre-COVID-19, the brewery put 70 percent of its beer in kegs. Shifting to packaging has “softened the blow, but hasn’t allowed us to grow back to where we were,” he says. “We’re operating at about 50 percent.”

Even as alarmist headlines declare Americans are drinking shocking amounts of alcohol at home, for many breweries, off-premise sales can’t make up for the loss of on-premise sales. Part of the trouble is that once the beer is in cans, breweries still have to find ways to get their products into drinkers’ hands.

Greater placement in mainstream grocery chains may seem like an attractive way to reach customers, but it’s an uphill battle. Chains typically refresh their lineups twice a year, in spring and fall. “Even though the total volume of packaged beer is up, the market for packaged beer has actually tightened. When there are such good sales going through grocery stores, they’re loath to add new items. They don’t need to,” Edmunds explains. “If you’re in there and you have those chain placements, things are going gangbuster right now. But if you don’t, it’s hard to crack into it.”

Luckily for small operations like Denver’s Lady Justice Brewing, a wave of localism has risen to support community brewers that may not have the ability (or interest) to access widespread distribution. Kate Power, Betsy Lay, and Jen Cuesta used a fundraiser to launch the one-barrel brewery as a philanthropic project in 2016. It was one of, if not the first to introduce membership beer sales to Colorado through its Community-Supported Beer (CSB) program. Customers paid ahead of time to provide funds to brew the beer, and all profits went to local organizations benefiting women and girls.

The trio grew into a new taproom in March, but when Denver locked down, they revived the CSB concept and immediately saw record demand. “People feel good when they buy our beer because they know it’s going to help their own communities. It’s a way to help people stay connected,” Lay says. “The neighborhood has really been investing in us.”

Beer delivery has also seen a huge jump, with 30.5 percent more breweries saying they are delivering beer locally, 3.8 percent newly partnering with third-party delivery platforms, and 4.8 percent adding direct-to-consumer shipping, according to the Brewers Association. Loosened alcohol delivery laws have allowed brewers to list products on services like Doordash and UberEats. Stylman, who has seen how restaurants have struggled with those platforms, says Threes launched direct-to-consumer delivery in-house in order to avoid fees, rehire furloughed taproom workers, and offer subscriptions for cases of its flagship beers.

Online beer retailer Tavour has also seen a bump in business. Once mostly a platform for craft geeks to drop big money on rare brews, lately Tavour has welcomed more casual customers who typically shop at brick-and-mortar retail. The online market usually adds seven new breweries a month, but 47 have joined since March. Megan Birch, director of marketing for Tavour, says about half of those entirely self-distributed before partnering with the service, and a handful only sold through their own taprooms. Big names like Mikkeller and cult brands like Parish Brewing have listed beers that may have never appeared on such a site under ordinary circumstances. “You’re definitely seeing breweries that never wanted to work with us because they never really needed to,” Birch says.

Even as brewers adapt to the new normal, new challenges appear all the time. In April, brewers worried about a shortage of CO2, a byproduct of ethanol production used to carbonate beer. Demand for ethanol, which is mixed with gasoline, dropped during the pandemic, and plants halted production. While plummeting ethanol sales didn’t end up harming breweries as much as expected, the episode illustrated how supply remains extremely vulnerable to global developments. More recently, with nearly every brewery transitioning to packaged beer, more pressure has fallen on supply chains for raw materials. “All of the glass suppliers, all of the label suppliers, all of the can suppliers in particular have seen increased lead time,” Edmunds says.

Looking ahead, as the nation officially experiences a recession, Edmunds expects financially cautious drinkers may dampen the explosive growth the craft industry has seen over the last decade, both in beer prices and product availability. “Five years ago the $16 six-pack was the outlier. Now it’s routine to see beers go for $20 or even $25 for a four-pack,” he says. “I don’t think we’ll see beer prices fall like crazy for your average six-pack, but more for that super-premium tier.” He also expects the market to curb “SKUmaggedon,” the proliferation of brands and niche releases. Both at retail and bars, Edmunds says, owners may eschew the constant churn of new products for surefire sellers. “Wholesalers but also retailers have wanted to have a reset on that, to go back to a more controlled method for getting beer out,” he adds.

The pandemic has also united breweries across regions to call for a reset on another aspect of distribution: local regulations that have limited or complicated alcohol delivery. The pandemic has inspired legislators in some areas to relax those rules temporarily, but changes could become permanent if brewers get their way.

“The temporary orders and the demonstrated ability of state regulators to enforce them have … shown that beer to go can be done responsibly,” Brewers Association president and CEO Bob Pease says. Consumer caution could choke on-premise sales for years to come; Pease emphasizes that responsible, flexible distribution will help save countless businesses and jobs. Long-term policy changes could provide a silver lining to the economic crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic may last months or years, but it has also permanently changed how some brewers do business. “I was talking to another brewer who said, this is great, we’re selling stuff on our website, but we can’t wait until it goes back to the way things were. That is decidedly not our approach,” Stylman says. Digital sales and delivery will remain “connective tissue” for the brewery long into recovery.

That may be wise, as the pandemic could affect consumer demand for a long time to come. “There are a lot of people who have really gotten used to staying at home,” Birch says, “and when everything does open up, they’re not really going to want to go out. It’s so much easier to just get beer delivered to their house.”

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2N5sxDb

via Blogger https://ift.tt/37CoKXn

0 notes

Text

How Coronavirus Could Change the Way You Get Your Favorite Craft Beer added to Google Docs

How Coronavirus Could Change the Way You Get Your Favorite Craft Beer

Mihai_Andritoiu/Shutterstock

Competition is fierce for cans, labels, and customers as breweries rush to package their beer for home drinking

It’s been a rough couple of months for craft beer. Like the coffee and wine industries, the entire beer ecosystem was upended as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered breweries, closed bars, and scared people away from beer shops. “March was kind of a bloodbath, financially speaking,” says Josh Stylman, co-founder of Threes Brewing in Brooklyn. “If you had asked me two months ago, I would have said I don’t know if our company is going to make it.” And that’s coming from a well-known, award-winning brewery in a huge market.

The pandemic has forced some breweries to close, and while COVID-19 has certainly pummeled the beer business, recent data from the Brewers Association shows many brewers are optimistic about their chances of survival. Operations that remained open the last few months found new ways to serve customers; others are now reopening alongside bars in some states.

Still, the crisis has forced breweries to completely reimagine operations. While bars and taprooms were forced to close, demand for beer remained through the darkest hours of lockdowns (plenty of socially distanced people still want to drink at home). Instead, the major disruptions were in distribution. According to Bart Watson of the Brewers Association, before the pandemic, 10 percent of an average American brewery’s output went into kegs, and that beer would go on to be sold on draft at bars, restaurants, and breweries’ own taprooms. For craft brewers, that number was much higher, nearly 40 percent, and they especially relied on in-house taprooms and brewpubs.

The rest went into off-premise sales like cans and bottles. But as on-premise sales dried up completely, brewers had to repackage their beer any way they could. “As soon as we closed, we decided any drop of liquid that can go in a can needs to go in a can,” Stylman says. While Threes had already been canning its beer for a few years, the shift required recalculating the brewery’s entire operation, costing time and money. “We just ordered a million different kinds of boxes to find the best one. We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

“We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

Some breweries that were forced to pivot to repacking use growlers or crowlers, relatively affordable entries into packaging for many small breweries. Crowler machines or other manual can seamers only cost a few thousand dollars, but they’re labor intensive, they’re usually filled and sold directly from taprooms (not at retail), and their DIY packaging doesn’t provide the best shelf life. Other brewers that never canned before have partnered with mobile canning companies like Codi Manufacturing or Mobile Canning, some of which have provided discounts or donated labor to help the struggling industry keep afloat. A few brewers, unable to redirect their entire stock into packages, had to dump beer that couldn’t be moved.

Pivoting may be more difficult depending on how a brewery’s business was spread across sales channels before the pandemic. Brewmaster Ben Edmunds of Breakside Brewery in Portland, Oregon, for instance, says pre-COVID-19, the brewery put 70 percent of its beer in kegs. Shifting to packaging has “softened the blow, but hasn’t allowed us to grow back to where we were,” he says. “We’re operating at about 50 percent.”

Even as alarmist headlines declare Americans are drinking shocking amounts of alcohol at home, for many breweries, off-premise sales can’t make up for the loss of on-premise sales. Part of the trouble is that once the beer is in cans, breweries still have to find ways to get their products into drinkers’ hands.

Greater placement in mainstream grocery chains may seem like an attractive way to reach customers, but it’s an uphill battle. Chains typically refresh their lineups twice a year, in spring and fall. “Even though the total volume of packaged beer is up, the market for packaged beer has actually tightened. When there are such good sales going through grocery stores, they’re loath to add new items. They don’t need to,” Edmunds explains. “If you’re in there and you have those chain placements, things are going gangbuster right now. But if you don’t, it’s hard to crack into it.”

Luckily for small operations like Denver’s Lady Justice Brewing, a wave of localism has risen to support community brewers that may not have the ability (or interest) to access widespread distribution. Kate Power, Betsy Lay, and Jen Cuesta used a fundraiser to launch the one-barrel brewery as a philanthropic project in 2016. It was one of, if not the first to introduce membership beer sales to Colorado through its Community-Supported Beer (CSB) program. Customers paid ahead of time to provide funds to brew the beer, and all profits went to local organizations benefiting women and girls.

The trio grew into a new taproom in March, but when Denver locked down, they revived the CSB concept and immediately saw record demand. “People feel good when they buy our beer because they know it’s going to help their own communities. It’s a way to help people stay connected,” Lay says. “The neighborhood has really been investing in us.”

Beer delivery has also seen a huge jump, with 30.5 percent more breweries saying they are delivering beer locally, 3.8 percent newly partnering with third-party delivery platforms, and 4.8 percent adding direct-to-consumer shipping, according to the Brewers Association. Loosened alcohol delivery laws have allowed brewers to list products on services like Doordash and UberEats. Stylman, who has seen how restaurants have struggled with those platforms, says Threes launched direct-to-consumer delivery in-house in order to avoid fees, rehire furloughed taproom workers, and offer subscriptions for cases of its flagship beers.

Online beer retailer Tavour has also seen a bump in business. Once mostly a platform for craft geeks to drop big money on rare brews, lately Tavour has welcomed more casual customers who typically shop at brick-and-mortar retail. The online market usually adds seven new breweries a month, but 47 have joined since March. Megan Birch, director of marketing for Tavour, says about half of those entirely self-distributed before partnering with the service, and a handful only sold through their own taprooms. Big names like Mikkeller and cult brands like Parish Brewing have listed beers that may have never appeared on such a site under ordinary circumstances. “You’re definitely seeing breweries that never wanted to work with us because they never really needed to,” Birch says.

Even as brewers adapt to the new normal, new challenges appear all the time. In April, brewers worried about a shortage of CO2, a byproduct of ethanol production used to carbonate beer. Demand for ethanol, which is mixed with gasoline, dropped during the pandemic, and plants halted production. While plummeting ethanol sales didn’t end up harming breweries as much as expected, the episode illustrated how supply remains extremely vulnerable to global developments. More recently, with nearly every brewery transitioning to packaged beer, more pressure has fallen on supply chains for raw materials. “All of the glass suppliers, all of the label suppliers, all of the can suppliers in particular have seen increased lead time,” Edmunds says.

Looking ahead, as the nation officially experiences a recession, Edmunds expects financially cautious drinkers may dampen the explosive growth the craft industry has seen over the last decade, both in beer prices and product availability. “Five years ago the $16 six-pack was the outlier. Now it’s routine to see beers go for $20 or even $25 for a four-pack,” he says. “I don’t think we’ll see beer prices fall like crazy for your average six-pack, but more for that super-premium tier.” He also expects the market to curb “SKUmaggedon,” the proliferation of brands and niche releases. Both at retail and bars, Edmunds says, owners may eschew the constant churn of new products for surefire sellers. “Wholesalers but also retailers have wanted to have a reset on that, to go back to a more controlled method for getting beer out,” he adds.

The pandemic has also united breweries across regions to call for a reset on another aspect of distribution: local regulations that have limited or complicated alcohol delivery. The pandemic has inspired legislators in some areas to relax those rules temporarily, but changes could become permanent if brewers get their way.

“The temporary orders and the demonstrated ability of state regulators to enforce them have … shown that beer to go can be done responsibly,” Brewers Association president and CEO Bob Pease says. Consumer caution could choke on-premise sales for years to come; Pease emphasizes that responsible, flexible distribution will help save countless businesses and jobs. Long-term policy changes could provide a silver lining to the economic crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic may last months or years, but it has also permanently changed how some brewers do business. “I was talking to another brewer who said, this is great, we’re selling stuff on our website, but we can’t wait until it goes back to the way things were. That is decidedly not our approach,” Stylman says. Digital sales and delivery will remain “connective tissue” for the brewery long into recovery.

That may be wise, as the pandemic could affect consumer demand for a long time to come. “There are a lot of people who have really gotten used to staying at home,” Birch says, “and when everything does open up, they’re not really going to want to go out. It’s so much easier to just get beer delivered to their house.”

via Eater - All https://www.eater.com/beer/2020/6/16/21289665/craft-beer-microbreweries-drinking-alcohol-coronavirus-delivery-covid-19

Created June 16, 2020 at 11:26PM

/huong sen

View Google Doc Nhà hàng Hương Sen chuyên buffet hải sản cao cấp✅ Tổ chức tiệc cưới✅ Hội nghị, hội thảo✅ Tiệc lưu động✅ Sự kiện mang tầm cỡ quốc gia 52 Phố Miếu Đầm, Mễ Trì, Nam Từ Liêm, Hà Nội http://huongsen.vn/ 0904988999 http://huongsen.vn/to-chuc-tiec-hoi-nghi/ https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1xa6sRugRZk4MDSyctcqusGYBv1lXYkrF

0 notes

Text

Airbnb could file to go public this month

According to the Wall Street Journal, Airbnb could file confidentially to go public as early as this month. The same report states that Airbnb could follow that filing with an IPO before year’s end. Morgan Stanley and Goldman are helping the former startup with its IPO process, the Journal writes.

The news that Airbnb’s IPO could be back on caps a tumultuous year for the home-sharing unicorn, which promised in 2019 to go public in 2020. The company was widely tipped to be considering a direct listing before COVID-19 arrived, crashing the global travel market, and with it, Airbnb’s financial health.

Airbnb declined to comment on its IPO plans.

As travelers stayed home, the company was forced to sharply cut staff, and take on billions in capital at prices that compared to its late 2019-momentum looked rather expensive.

But since those blows, Airbnb has began to make noise about positive progress regarding its platform usage, and, implicitly, its financial performance.

In June Airbnb said that between “May 17 to June 6, 2020, there were more nights booked for travel to Airbnb listings in the US. than during the same time period in 2019” and that “globally, over the most recent weekend (June 5-7), we saw year-over-year growth in gross booking value” for “the first time since February.”

And in July, the company that said that its users had “booked more than 1 million nights’ worth of future stays at Airbnb listings” globally in a single day, the first time since March 3rd that that had happened.

Precisely how far Airbnb has financially clawed its way back is not clear. But the company’s cost basis in the wake of its layoffs could lower the revenue base it needs to recover to reach something akin to profitability, a traditional IPO benchmark though one that has lost luster in recent years.

And with local travel taking off — slowly-improving airline occupancy rates are, therefore, not indicative of Airbnb’s performance or health — the company could have retooled its business in the wake of COVID to something that can still put up attractive revenues at strong margins.

Needless to say I am hype to read the Airbnb S-1, so the sooner it drops the happier I’ll be. Getting an in-depth look at what happened to the unicorn during COVID-19 is going to be fascinating.

Airbnb joins DoorDash, Coinbase, Palantir, and others on our IPO shortlist. More as we have it.

0 notes

Quote

Mihai_Andritoiu/Shutterstock

Competition is fierce for cans, labels, and customers as breweries rush to package their beer for home drinking

It’s been a rough couple of months for craft beer. Like the coffee and wine industries, the entire beer ecosystem was upended as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered breweries, closed bars, and scared people away from beer shops. “March was kind of a bloodbath, financially speaking,” says Josh Stylman, co-founder of Threes Brewing in Brooklyn. “If you had asked me two months ago, I would have said I don’t know if our company is going to make it.” And that’s coming from a well-known, award-winning brewery in a huge market.

The pandemic has forced some breweries to close, and while COVID-19 has certainly pummeled the beer business, recent data from the Brewers Association shows many brewers are optimistic about their chances of survival. Operations that remained open the last few months found new ways to serve customers; others are now reopening alongside bars in some states.

Still, the crisis has forced breweries to completely reimagine operations. While bars and taprooms were forced to close, demand for beer remained through the darkest hours of lockdowns (plenty of socially distanced people still want to drink at home). Instead, the major disruptions were in distribution. According to Bart Watson of the Brewers Association, before the pandemic, 10 percent of an average American brewery’s output went into kegs, and that beer would go on to be sold on draft at bars, restaurants, and breweries’ own taprooms. For craft brewers, that number was much higher, nearly 40 percent, and they especially relied on in-house taprooms and brewpubs.

The rest went into off-premise sales like cans and bottles. But as on-premise sales dried up completely, brewers had to repackage their beer any way they could. “As soon as we closed, we decided any drop of liquid that can go in a can needs to go in a can,” Stylman says. While Threes had already been canning its beer for a few years, the shift required recalculating the brewery’s entire operation, costing time and money. “We just ordered a million different kinds of boxes to find the best one. We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

“We never did this before. We’re inventing a supply chain from nothing.”

Some breweries that were forced to pivot to repacking use growlers or crowlers, relatively affordable entries into packaging for many small breweries. Crowler machines or other manual can seamers only cost a few thousand dollars, but they’re labor intensive, they’re usually filled and sold directly from taprooms (not at retail), and their DIY packaging doesn’t provide the best shelf life. Other brewers that never canned before have partnered with mobile canning companies like Codi Manufacturing or Mobile Canning, some of which have provided discounts or donated labor to help the struggling industry keep afloat. A few brewers, unable to redirect their entire stock into packages, had to dump beer that couldn’t be moved.

Pivoting may be more difficult depending on how a brewery’s business was spread across sales channels before the pandemic. Brewmaster Ben Edmunds of Breakside Brewery in Portland, Oregon, for instance, says pre-COVID-19, the brewery put 70 percent of its beer in kegs. Shifting to packaging has “softened the blow, but hasn’t allowed us to grow back to where we were,” he says. “We’re operating at about 50 percent.”

Even as alarmist headlines declare Americans are drinking shocking amounts of alcohol at home, for many breweries, off-premise sales can’t make up for the loss of on-premise sales. Part of the trouble is that once the beer is in cans, breweries still have to find ways to get their products into drinkers’ hands.

Greater placement in mainstream grocery chains may seem like an attractive way to reach customers, but it’s an uphill battle. Chains typically refresh their lineups twice a year, in spring and fall. “Even though the total volume of packaged beer is up, the market for packaged beer has actually tightened. When there are such good sales going through grocery stores, they’re loath to add new items. They don’t need to,” Edmunds explains. “If you’re in there and you have those chain placements, things are going gangbuster right now. But if you don’t, it’s hard to crack into it.”

Luckily for small operations like Denver’s Lady Justice Brewing, a wave of localism has risen to support community brewers that may not have the ability (or interest) to access widespread distribution. Kate Power, Betsy Lay, and Jen Cuesta used a fundraiser to launch the one-barrel brewery as a philanthropic project in 2016. It was one of, if not the first to introduce membership beer sales to Colorado through its Community-Supported Beer (CSB) program. Customers paid ahead of time to provide funds to brew the beer, and all profits went to local organizations benefiting women and girls.

The trio grew into a new taproom in March, but when Denver locked down, they revived the CSB concept and immediately saw record demand. “People feel good when they buy our beer because they know it’s going to help their own communities. It’s a way to help people stay connected,” Lay says. “The neighborhood has really been investing in us.”

Beer delivery has also seen a huge jump, with 30.5 percent more breweries saying they are delivering beer locally, 3.8 percent newly partnering with third-party delivery platforms, and 4.8 percent adding direct-to-consumer shipping, according to the Brewers Association. Loosened alcohol delivery laws have allowed brewers to list products on services like Doordash and UberEats. Stylman, who has seen how restaurants have struggled with those platforms, says Threes launched direct-to-consumer delivery in-house in order to avoid fees, rehire furloughed taproom workers, and offer subscriptions for cases of its flagship beers.

Online beer retailer Tavour has also seen a bump in business. Once mostly a platform for craft geeks to drop big money on rare brews, lately Tavour has welcomed more casual customers who typically shop at brick-and-mortar retail. The online market usually adds seven new breweries a month, but 47 have joined since March. Megan Birch, director of marketing for Tavour, says about half of those entirely self-distributed before partnering with the service, and a handful only sold through their own taprooms. Big names like Mikkeller and cult brands like Parish Brewing have listed beers that may have never appeared on such a site under ordinary circumstances. “You’re definitely seeing breweries that never wanted to work with us because they never really needed to,” Birch says.

Even as brewers adapt to the new normal, new challenges appear all the time. In April, brewers worried about a shortage of CO2, a byproduct of ethanol production used to carbonate beer. Demand for ethanol, which is mixed with gasoline, dropped during the pandemic, and plants halted production. While plummeting ethanol sales didn’t end up harming breweries as much as expected, the episode illustrated how supply remains extremely vulnerable to global developments. More recently, with nearly every brewery transitioning to packaged beer, more pressure has fallen on supply chains for raw materials. “All of the glass suppliers, all of the label suppliers, all of the can suppliers in particular have seen increased lead time,” Edmunds says.

Looking ahead, as the nation officially experiences a recession, Edmunds expects financially cautious drinkers may dampen the explosive growth the craft industry has seen over the last decade, both in beer prices and product availability. “Five years ago the $16 six-pack was the outlier. Now it’s routine to see beers go for $20 or even $25 for a four-pack,” he says. “I don’t think we’ll see beer prices fall like crazy for your average six-pack, but more for that super-premium tier.” He also expects the market to curb “SKUmaggedon,” the proliferation of brands and niche releases. Both at retail and bars, Edmunds says, owners may eschew the constant churn of new products for surefire sellers. “Wholesalers but also retailers have wanted to have a reset on that, to go back to a more controlled method for getting beer out,” he adds.

The pandemic has also united breweries across regions to call for a reset on another aspect of distribution: local regulations that have limited or complicated alcohol delivery. The pandemic has inspired legislators in some areas to relax those rules temporarily, but changes could become permanent if brewers get their way.

“The temporary orders and the demonstrated ability of state regulators to enforce them have … shown that beer to go can be done responsibly,” Brewers Association president and CEO Bob Pease says. Consumer caution could choke on-premise sales for years to come; Pease emphasizes that responsible, flexible distribution will help save countless businesses and jobs. Long-term policy changes could provide a silver lining to the economic crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic may last months or years, but it has also permanently changed how some brewers do business. “I was talking to another brewer who said, this is great, we’re selling stuff on our website, but we can’t wait until it goes back to the way things were. That is decidedly not our approach,” Stylman says. Digital sales and delivery will remain “connective tissue” for the brewery long into recovery.

That may be wise, as the pandemic could affect consumer demand for a long time to come. “There are a lot of people who have really gotten used to staying at home,” Birch says, “and when everything does open up, they’re not really going to want to go out. It’s so much easier to just get beer delivered to their house.”

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2N5sxDb

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/06/how-coronavirus-could-change-way-you.html

0 notes