#Eŋenty

Text

The Brewer Cat

Far north of here in Ŋísh the land of meadows, Ɵórí SHóry-l was well known as a brewer. When she was born she lived in a small group of compounds, but by the time she was thirty-eight years old it was growing toward becoming a city. Several courts had already asked her to do her work in their cities, but she preferred to stay with her family.

Ɵórí loved children more than anything. There was scarcely a single young child in the SHóry compound who could not call her a parent, and she had a tattoo for each of them.[1] She didn’t want to give up any of her children, nor did she want to ask them to move from the meadows and woods they knew. So she refused the courts, one after another, when they asked her to move. But it was well known that anyone with enough humility to walk into her house would leave with whatever they had come looking for—a barrel of beer to make the soul sing, a salve to soothe the fiercest burn, even medicines to heal tongues that had begun to stutter and breath that had begun to falter. Many small gods came to taste her beer and begged to be bound to her, but she always said she did not need any more help. Brewing was a private thing; sharing her brews a public one.

Now, one month a youth dressed in green[2] came to the gate of Ɵórí’s house. Ɵórí’s young daughter Íváŋ let em in and offered food and introduced em to the small gods of the household. In exchange the youth hummed a tune like the dark of a forest floor spattered with points of light. Íváŋ already suspected what e was, but when she asked how soon e would get yr first tattoo e just laughed, and yr eyes flashed, and she knew for certain.

Íváŋ asked what kind of brew the youth was looking for, and how e meant to pay. “Thirteen barrels of beer fit for the great gods,” e said, and smiled to show all yr teeth. “I will arrange my payment with Ɵórí the Brewer.[3] May I speak to her?”

“She is at work,” said Íváŋ, “but I will sit with you until she is done.”

The full moon was well above the horizon when Ɵórí came out of her shed for supper and found a youth dressed in green entertaining her family with the dramatic tale of a diplomat who got into a riddle contest with 18 Dragon Gathers Starlight. She liked the youth as much as her family did; when supper was over they were already becoming friends. Ɵórí and the youth sat in the courtyard together drinking beer and looked up through the tree branches that cut the full moon into shards.

“This is very good beer,” said the youth. “But do you make beer that is better than this? Do you make beer fit for the great gods?”

“Some people have told me so,” said Ɵórí. “I suppose it depends on whether the great gods have high expectations.”

“Very high expectations,” said the youth. “It must be beer whose very smell could give a small god the strength to uproot a tree.”

“And when do you need it?”

“Thirteen months from today, in the morning.”

Ɵórí did not ask how the youth would pay. The great gods know better than to cheat an honest woman.

The next morning the youth with the flashing eyes was gone and yr bed seemed not to have been slept in. Ɵórí went into her shed and began to think of recipes for a beer fit for the great gods.

In the seven months that followed the beer of Ɵórí the Brewer surpassed everything she had made before. It smelled so good that the head of household had to hire a spirit-binder to keep small gods away from the brewing shed so Ɵórí could concentrate. But Ɵórí was not satisfied. “This is a beer fit for small gods,” she told her head of household, as the woman’s tattooed toes curled in delight to taste it. “It is not fit for the great gods. Ask the young children to find every good herb and spice in the forest.”

In the twelfth month Ɵórí was still not satisfied, and she had grown very worried. If she could not offer a worthy beer to the House of Glass,[4] what would become of her? She sat until dawn in her shed with her hands clasped over her diaphragm, and answers did not come to her.

Just as the sun’s light seared a thin red line onto the wall of the shed, something else came through the window. It was a grey cat that jumped up on top of the high shelf where Ɵórí could not reach it. “You are making a beer fit for the great gods,” said the cat, looking down at her with eyes like half-moons. “So I hear, and so I smell.”

“Perhaps I am, and perhaps not,” said Ɵórí. She was weary. “You must be a clever small god to get in past the bound-gods guarding my shed. I suppose you want to taste my beer.”

“I won’t refuse,” said the cat, licking its lips. “But my reason for coming here is that I want to help you. You only have one month left to make a beer fit for the great gods, and still you don’t know how to do it.”

Ɵórí ladled some beer into a shallow bowl and placed it onto the ground for the cat, which jumped down and began to drink it. As it drank it became larger until it stood as tall as Ɵórí’s waist. “This is certainly a beer fit for small gods!” said the cat. “Now tell me, what have you been doing?”

Ɵórí explained and the cat watched her brew a batch of beer. “This is as good as beer can be made using human arts,” said the cat when it was finished. “But to make beer fit for the great gods you must use godly arts.” It arched its back and some of the hairs flew off to land in the fire, where they spat violet sparks. It dipped its paw into the blood-warm beer and whisked its tail so the steam came up in perfect spirals like nautilus shells; and it sang a song. Of course I cannot tell you what the song is! I’ve been sworn to secrecy! Any other kind of magic might need to be written out, but brewing is wilder magic than what wrote the world. Brewing is a magic that has forgotten ink; it is a magic blessed by the little sister of the gods.[5]

Now when Ɵórí tasted the beer she nearly swooned and her skin seemed to glow. Now when the cat tasted the beer it grew to the size of a lion and began to purr like an earthquake. “Now this is a beer fit for great gods!” it rumbled. “Good! Let us make more!”

They worked night and day and night to make eighteen barrels of the beer fit for the great gods, and four days before the appointed day they were finally able to rest. Ɵórí’s daughters and young children and their other parents had prepared a huge feast. They had roasted roots and locust-flour pancakes with soft cheese. They had porridge with sausage and tender fried grubs and delicate fruit pies. And of course they had beer! You’ve never seen such beer. Sweet beer cakes, small beer for the young children, and everyone had a taste of the beer fit for the great gods. People came from all over Ŋísh to have a taste, but three barrels were all for the House of SHóry. Three days later they were still drunk!

On the morning of the fourth day Ɵórí got her daughters to help her roll the barrels out into the courtyard, and no sooner were they all laid out than the youth in green came knocking on the gate!

E was ushered inside and got to taste the beer. “Yes!” e crowed, glowing like a firefly. “This is a beer fit for the great gods!” A bird flew up off yr shoulder, and soon a procession of teŋríech[6] came in through the gate with saddles ready to take the casks of beer. With them was a solemn person who was not a youth but who did not have the chin tattoo of a grown woman. E was likewise dressed in green, and e presented Ɵórí with a mirror taller than a woman and as wide as two. The frame was brass, carved with every kind of flower and leaf, and all around the edge were protective charms in beautiful calligraphy.

The procession rode away, and Ɵórí put up the mirror in the front hall of the house.

Of course, this was not the last time she saw the youth! She was the favorite brewer of the great gods until she died; but somehow it was always that youth with the flashing eyes who came to give her the commission. She would invite in that great god[7] and sit in the window with em, and with a grey cat the size of a lion curled up under it; and they all three would drink beer until the moon rose.

-----------------------------

Notes on the text

[1] A woman would not go to the trouble of getting a tattoo commemorating the birth of a child who she did not intend to have a large part in raising; this indicates that Ɵórí is not absorbed in her work but rather does what she does for the sake of her community.

[2] In plays, actors wear green to indicate that their character is a god or spirit in disguise. This is generally considered to be an artistic signal, not something that is strictly true in the story.

[3] This would be “Ɵórí Ɵóróshú,” indicating that Ɵórí’s name was picked as a sort of pun (although it’s also a reasonably common name in the north).

[4] Ɵórí assumes, rightly, that the youth dressed in green is one of the children

of 6 Mirror of the Forest, whose house is known to be in the dark forest north of Ŋísh.

[5] Despite not being the youngest among the great gods, 10 Creeping Mushrooms is known as their little sister. 10 Creeping Mushrooms is the matron of not only decay but also of fermentation. She is also something of a trickster figure or wild god, considered to be the matron of the large quick salamanders known for carrying off sacks of locusts.

[6] A teŋrúech is an animal with spreading toes and small horns, often used to carry or pull loads. They are not large enough for an adult woman to ride, however.

[7] As listeners to the story we know that this youth was 54 Signal Flash, the youngest child of Glass and the most mischievous; and I daresay Ɵórí had some idea as well, even if e never told her yr name.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

did YOU know that every human soul is a wasp? it’s true! sometimes spirits and wind gods ride ‘em around.

12 notes

·

View notes

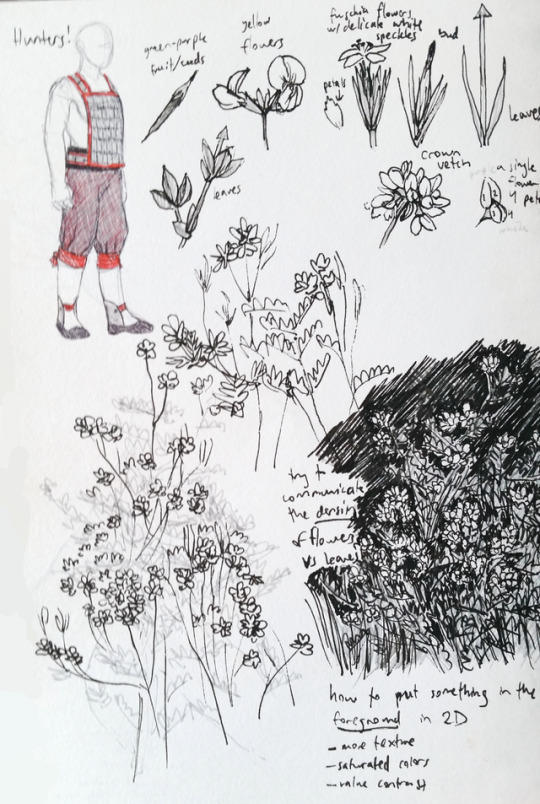

Photo

misc. thinking about the idea of storing things in eggshells--which are designed to be extremely tough under a very specific set of circumstances

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

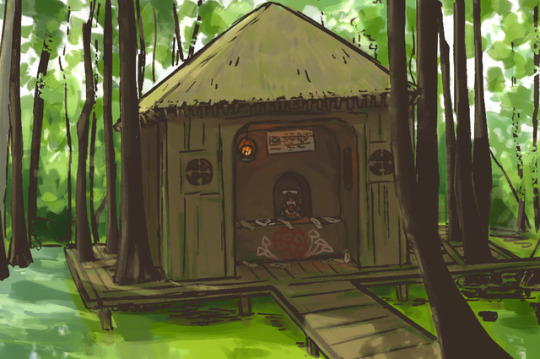

Yeah instead of a liveblog tonight I brought some pictures of SHúrshá CHely-l, who accidentally got blessed with the Sight and then turned into the spirit of a capybara/deer animal

#SADLY e is a spirit now. forever. sux to be you#don't put on animal skins offered to u by strange spirits is the lesson here#art#Eŋenty

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

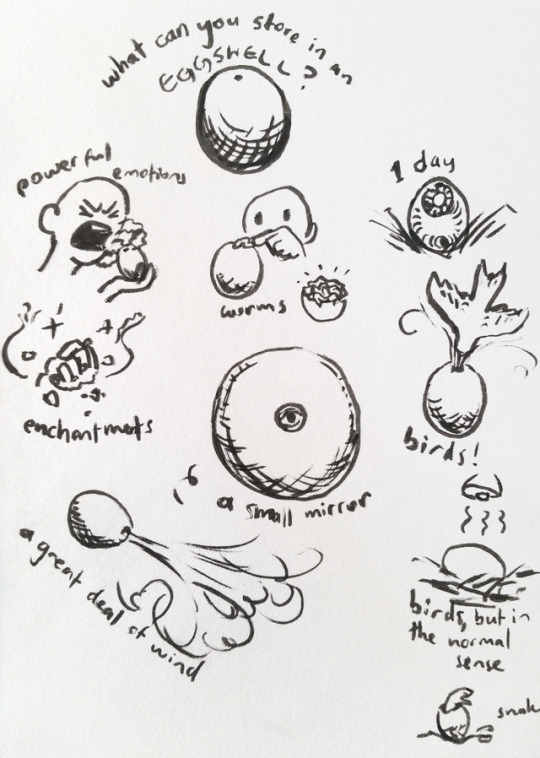

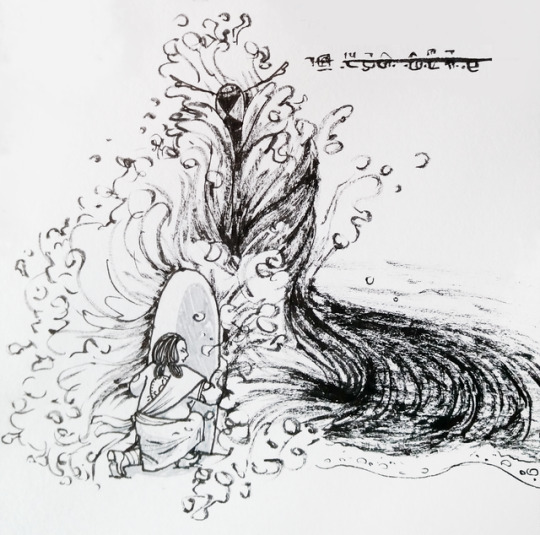

Famous hero Áŋver Glass-Chest attempting to negotiate a peaceful settlement with 19 Coastal Typhoon, a water god of conquest

#the good news: Áŋver ends the drought and founds one of the Ancient Houses!#the bad news: her family is cursed with endless thirst for 3 generations#Eŋenty#art#that's a shield by the way not a surfboard#ahaa

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

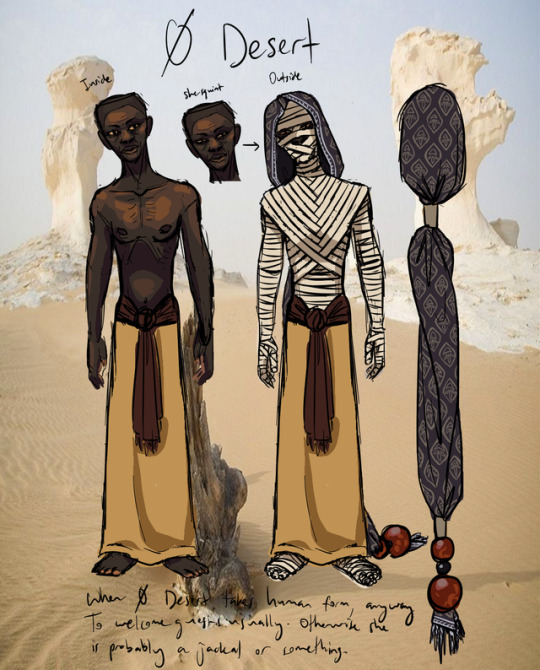

to add Interest I stuck a background on there. I decided the White Desert is what her home looks like, despite the fact that it is not the desert that lives in my heart. the beads on her headdress are jasper and jet. they’re not really shiny any more because she drags them through the sand so often.

#mmm probably she wears the headdress indoors too because it's awesome#have I MENTIONED recently that she has a bottomless well in her underground house that tells the future??#Eŋenty#art

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

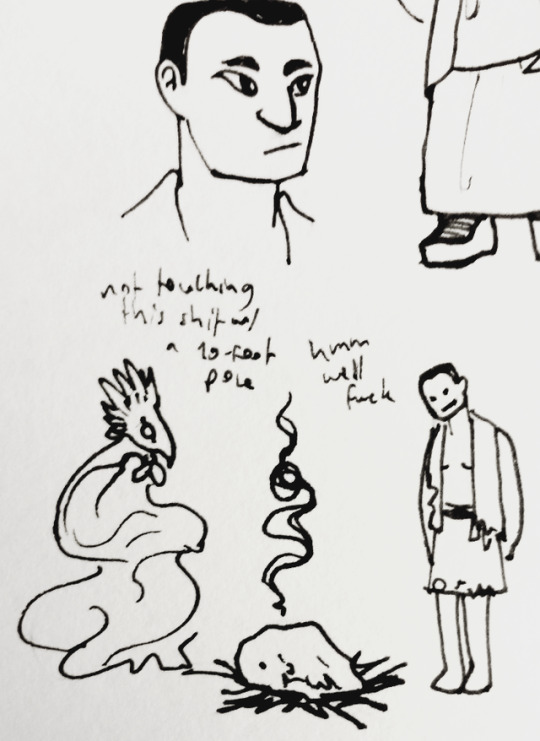

my take on the epic of the sky-iron fence

#small gods cannot touch sky-iron obviously#although normal iron is fine#it's the uh heightened nickel content#spirits don't like nickel#fuck if I know#Eŋenty#art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the meeting of Áŋver Glass-Chest and 19 Coastal Typhoon

Áŋver plants her feet like the slopes of a mountain, as is her custom. She plants her shield in the black sand beside her. And she calls to the sea.

"19 'RRóvántú Shúchetáŋ! I would negotiate! I am Áŋver Glass-Chest, She-Who-Makes-Her-Intent-Visible!"

The water rises in front of her, a growing hurricane. Froth hangs in the air around it, and she tightens her grip on her shield. Finally the mask appears at the top of the water-pillar, and she hears the god's voice.

"Human," says the god, as if this is the greatest insult she can think of. Her voice is crashing waves foaming into spray over the black jagged rocks of the Ex‘rráshy-l coast. "Leave. I have no need to speak with you."

"Shall I name you coward?" asks Áŋver.

"You could try," says the god without care.

"Shall I name you false god," Áŋver continues. She is finding her rhythm.

"Shall I name you one who cares not

for the domain under her protection?

Shall I name you oathbreaker or

shall I name you worm?

Speak with me!

Prove me wrong."

"Then we will do this." the water roars. "Make peace with your defeat before it happens."

"Shall I name you trespasser?

A fragile bird, a slow mole.

Your words have no power over me and

to see you try is nothing but amusement.

I will play your game.

I name you One-Who-Is-About-To-Die!"

Áŋver shakes her head, tossing her low buns over her shoulders. Doing this, she shakes off the name. She refuses to allow it purchase.

"I name you Liar!

I name you Speaker-Of-Falsehoods-That-Will-Not-Become-Truths!

I name you One-Who-Has-Not-The-Strength-To-Enforce-Her-Will!"

The pillar begins to fall forward, curling as a cresting wave. Áŋver takes up her shield again and digs it deep into the sand, kneeling behind it to brace it. The water roars:

"I name you Air-Breather!

I name you One-Who-Drowns!"

"You can try!" Áŋver screams.

"I name you Gentle-Tide!

I name your waves Canyon!

I name them Split-Before-My-Shield!"

And they do. The god's conviction is not strong. She has anger, yes, but it is only because she did not expect to be challenged. She is barely a full-moon god at all, still young.

"You do not have power to hurt me.

You are near to a small god.

If you cannot protect this land

as befits a great god, then hear:

I will protect it in your stead."

"I am not a god of protection," growls the god. "I am a god of war."

"Then you are no god.

I name you Wild Spirit.

I name you One-Who-Protects-Only-Herself.

I claim your authority over this land.

A ruler is one who protects

her people from harm."

"Try if you will," says the god, but she is not speaking in cadence. Her words have no more power to contest Áŋver's claim. Áŋver will win here, even if she cannot protect Ex‘rrásh either. "You have no power to return the water to the land. I alone can do that here. Small gods of water will not help you if I forbid it, o Queen of Ex‘rrásh."

"I am willing to negotiate," says Áŋver, "as I am now your neighboring ruler, one who cares for the land as you care for the sea. Let me serve you, once. You are a god of war. You will someday need a mediator."

"I will let you serve me once." The pillar of the god sinks low until she is barely a swell of the waves, and only her mask is still surrounded by foam. "I will let your children serve me once, and their children, and then your line will be free."

"My children may not be mediators," Áŋver warns.

"I will make what I need of them. Do you agree?"

"By my oath I will serve you

once during my life, as will

my children, and their children.

If during our lives you bring drought

to this land again,

the oath is broken."

"By my oath I will stave off drought

from this land, and require only

one service of you, and

your children, and your children's children.

You will thirst

just once, but all your life.

Should you try to break this oath

mine will be broken as well."

And the god laughs; the swell disappears; she is gone. Áŋver stands alone.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Translation notes:

1.“She-Who-Makes-Her-Intent-Visible.” The original is closer to “She-Who-Makes-Her-Lungs-Visible.” This makes use of the metaphoric connection in Eŋenty culture between the breath and the living spirit of a person. A similarly fanciful phrase in English might be “She-Who-Bares-Her-Heart,” although this doesn’t quite capture the implication of transparency in speech. Her epithet Glass-Chest is closer to “Glass-Diaphragm;” the word óhí’rrú indicates the part of the body where the power of the voice and breath comes from.

2. “Speaking in cadence.” This is a translation for a single verb, γíettúə. It refers to the mode of speech used in formal flyting, epic poetry, and magical contracts. I didn’t try to preserve the rhythm here, opting for a more direct translation by meaning. The rhythm is generally alternating long syllables (high tone) and short syllables (a tone a perfect fourth lower).

3. “Barely a full-moon god at all.” Eŋentí has three grammatical genders: new moon (which I translate as “it”), half moon (“e”), and full moon (“she”). Among humans, half-moon refers exclusively to children and new moon conjugations refer to inanimate objects. The great gods, however, may claim any of the grammatical genders. Here Áŋver compared 19 Coastal Typhoon to a human child.

4. The Eŋentí language very rarely uses adjectives. They aren’t really a separate part of speech, and are more considered exceptions in the rare cases that they exist. I tried to translate the text exactly where possible, and omitting adjectives in favor of constructions that sound a little unnatural in English helps give the feel of Eŋentí.

5. The original exaggerated Áŋver’s lisp (for mediators and other magic-workers, this is due to a tongue piercing) for dramatic purposes, but because English speakers don’t associate the lisp with power I chose to use somewhat formal and impressive language instead. In Eŋentí the lisp is rendered by replacing the letters sh, t, and tt with h, which is pronounced similarly to the pinyin x.

#now with translation notes#which are really the best part honestly#especially since some of my followers are CONLANG NERDS#does emma follow me idr#Eŋenty#you'll find an illustration of this scene in the tag#fiction

10 notes

·

View notes