#Cmentarz Św. Józefa

Text

TYSIĄC ZNICZY BOHATEROM-MANCHESTER

Czwartego listopada najciemniejszy zakątek cmentarza St.Joseph’s w Manchesterze, rozświetliły płomienie tysiąca biało czerwonych zniczy. Jak co roku od 2016 z okazji dnia Wszystkich Świętych zadbaliśmy o pamięć Polskich bohaterów, spoczywających tak daleko od ojczyzny. Dzięki czytelnikom mojego bloga i dzięki pomocy pana Grzegorza Serafin, zakupiliśmy i sprowadziliśmy z Polski tysiąc zniczy,…

View On WordPress

#1 dywizja#1SBS#2 Korpus#Armia#Bohater#bohaterom#Bolesław#Bożego#Brytania#Cmentarz Św. Józefa#druga#Gerhard#godność#groby#Kamil#Karol#Konig#Kozbuwoski#Krajowa#Manchester#Manchesterze#Marynarka#Miłośierdzia#Moston#pancerna#Parafia#Paraszewski#PCK#Peruta#polacy

0 notes

Text

https://tylkoszachy.blogspot.com/2023/07/nie-zyje-halina-szpakowska-medalistka.html

Smutna wiadomość dotarła do nas z Tczewa. 24 czerwca 2023 roku zmarła w wieku 95 lat HALINA SZPAKOWSKA, wielokrotna finalistka Mistrzostw Polski kobiet w szachach.

Uroczystości żałobne ŚP. Haliny Szpakowskiej odbędą się 11 lipca 2023 roku o godz. 13.00 w Kościele Parafialnym św. Józefa w Tczewie. Po mszy nastąpi odprowadzenie urny na Cmentarz przy ul. Gdańskiej w Tczewie.

0 notes

Photo

kuramek

Kaplica św. Józefa. Cmentarz Na Salwatorze.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Cmentarz na Rossie - Ross Cemetery

The most famous Vilnius cemetery is the Ross cemetery. It became famous at the end of the last and beginning of this century, and its attractiveness was further multiplied by the heart of Marshal Józef Piłsudski and his mother's ashes and numerous quarters of soldiers who fell in battle for those lands that many of their relatives must have left forever.

Sentiment and nostalgia are only small and additional aspects of looking at this great national necropolis. It is primarily a document of the history of this city and the land and its culture. Tens of thousands of people sit there, co-creating this beautiful city, whose silhouette shines through the branches of trees from cemetery hills covered with gravestones and monuments proclaiming their names and merits.

The Ross cemetery is the largest of three old Catholic Vilnius cemeteries, ie Bernardyński and Św. Peter and Paul, as well as Jewish and Protestant cemeteries that no longer exist today. It consists of old and new parts.

Stara Rossa, with an area of 6.2 hectares, plus Nowa, currently has a total of 10.8 hectares, and the size matches other newer cemeteries, such as Antoskolski, or the Orthodox one.

Situated less than a kilometer from the Gate of Dawn, it was the only remote cemetery that focused on the majority of Vilnius burials. The creation of the second cemetery (Bernardyński) at a similar distance (from the place of the former Spaska Gate) has slightly reduced the number of burials and in the mid-nineteenth century they were more or less equal and equally in terms of prestige. In the second half of the century, the Ross cemetery was more fashionable, gathering more and more magnificent tombstones and burials of meritorious people, and the graves of soldiers from the first and second wars elevated him to the rank of national pantheon. The greatest and unique feature that distinguishes the Rossa cemetery from many other famous necropolises is its landscape and natural values. They result from the topography of the city located in the valley of Wilia and Wilejka, surrounded by high moraine hills, deserving fully the name of "mountains", covered with forest or meadows.

Their low utility value for agricultural and construction purposes turned out to be high enough for the Rossa cemetery. Visiting it in 1915. The cemetery is vast and strangely beautiful. Its very unusual location: it spreads out terracedly on the slope of a rather sloping hill. A special charm is given to the old trees, growing densely and irregularly, like in the forest. Between them, they curl freely, climb up and down the path, twisting among the graves. At least it looks the oldest, the most distant, a bit wild and that is why the most beautiful part of this forest cemetery. In the summer, when the boughs are scarcely sunk by the branches covered with the thicket of leaves, the birds sing in the branches, and the earth will be covered with forest flowers, the cemetery in Ross must be marvelous. "

Situated on the upland of the southern part of the suburbs, the old cemetery covers an area rich in relief between the ravines of Rossa and November streets. At the fairly even and almost horizontal stretch of Ross Street, behind the eastern cemetery wall with the main gate, there is a parallel strip of western heights, from which four high hills rise distinctly. All this hillyness along with the hills descends steeply from the east into a vast valley divided into two parts by the Eastern Ridge, topped by a steep (fifth) hill. Both valleys connect a narrow gorge-passage at the promontory of the said Eastern Ridge. This place is a narrowing of the valley-ravine, along which runs the street of November, surrounded on both sides by the cemetery walls, the old cemetery and east of it. The area of "New Rossa", shaped similarly, but in a symmetrical arrangement, rises steeply from the street upwards with four more clearly formed hills, so that outside of them again fall into a valley, adjacent to the rear fence.

There are various forms of terrain, from almost flat fragments through gentler or steeper hills to precipitous hillsides. The difference in levels in this area, surrounded by cemetery walls, is over 30 m from the highest hill to the bottom of the valley, and from it the second one is lower to the ground level at the Ostra Brama. The area thus formed creates several different interiors and views and landscape shots, mainly ravines and paths, with extraordinary qualities, including the view from the main entrance. It also gives great views of the valleys, especially the helpful associations with the biblical Valley of Josaphat, and the hills crowned with crosses associated with Golgotha, and a monumental sequence of the Main Avenue, as well as the mausoleum cemeteries: Soldiers of Vilnius Self-Defense and wars 1919-1920 with the grave heart of Marshal J. Piłsudski. In addition, from the hill of the old cemetery, as well as some on the new one, there are views of the distant panorama of the Old Town with its temples and towers, all among old pines, birches, ash trees and oaks. Regardless of the artistic-architectural and commemorative-historical values, the cemetery area and landscapes themselves create a wonderful park, skillfully selected and used for the resting place of the inhabitants of old Vilnius.

In contrast to the regular European cemeteries located on the plains, Rossa is characterized by a spontaneous free arrangement of alleys and paths dictated by the aforementioned relief. They prevent the use of signs in the form of quarters, avenues, paths, etc. and force them to descriptively mark individual places.

There is no uniform and complete naming of particular fragments of the area of this cemetery landscape complex, except for only a few places, such as Wzgórze Literatów or Karpówka, or "near the chapel", and for descriptive purposes, the names indicated on the plan have been adopted here. These are the terms resulting from topography and landscape forms without creating new and unnamed names. They concern uplands, ridge, hills and valleys, and alleys on the highlands, roads in ravines and paths. Apart from these landmarks, there are chapels (cemetery and family-mortuary) that create architectural accents in a landscape filled with greenery and a mass of tombstones with a finer scale. A fairly rare network of irregular paths and paths creates shortcuts and gives unexpected scenic effects, but in the search for individual graves, forces you to walk between tombstones quite loosely (in comparison to western cemeteries) located in the field.

In such a vast and diverse area in terms of its shape, individual places gained a different prestigious rank, customarily created over time and with the arrival of burials. The most respected place was "near the cemetery chapel", where a large columbar with the oldest burials was created. Next to them, with time, appeared individual graves of meritorious people with distinctive artistic forms. The prolongation of this place on the cemetery plains were Helpful and Southern Hills, where several grave chapels, graves of family aristocrats and more impressive gravestones were created. The extreme northern hill, located near the gate and called the Writers' Hill, also gained a special rank, where a larger concentration of graves of writers and artists was created - a particularly exposed place. On the other hand, Aleja Główna, stretching along the cemetery fence from the side of Rossa Street, was not a particularly valuable place.

The oldest part of the cemetery is the South Valley, in which there are many oldest graves from the beginning of the last century; also later it was a place valued probably for its seclusion, quietness and sunlight. Effective places on the tops of the East Ridge ridge were also appreciated and emphasized by impressive grave monuments. Dolina Pomocna, the most shadowy and gloomy, had the smallest take and there were modest burials in general, tombstones were not characterized by greater artistic values.

The last, finally, the most prestigious place was Nowa Rossa, on the other side of ulica Listopadowa, which has not been completely filled to this day. The tombstones that were made there belong to the increasingly poor society and the poor hidden here in the times of the ongoing fall of crafts and the development of trash in the art of the cemetery. This area is used until now. Particularly exposed are two military cemeteries located at the corners before the entrances to the Old and New Rossa on relatively flat fragments of the area of this extensive cemetery complex.

The history of the cemetery at Rossa, as well as the name of this old suburb, have been poorly researched and documented, although they reach back to the distant Middle Ages. According to Teodor Narbutt, and especially valuable research results, Fr. Władysław Tołłoczki, it is known that this area from 1436 was the place of burying the dead, especially during the destruction of the sea. At that time he wore the name of Świętojurska Rossa, from the call of the Orthodox and later Uniate Orthodox Church of St. George, serving the local parish, which is a kind of formal jurisdiction, burned completely during the wars during the times of Jan Kazimierz and later not rebuilt. This cemetery area from the 2nd half of the 17th century was outside the line of new earth fortifications erected then for the south-eastern side of the city and probably survived until the last partition. The passage through the curtain of these embankments, flanked by a great bastion and a pilaster fault, was probably located on the axis of the ravine of the current Rossa street.

There is a note from 1690 about the burial of a Jesuit unknown in the area of the (cemetery?) Purchased from the Rosickis by this convent, concerning Rossy. This could, however, apply to a different part of its territory than the below-mentioned cemetery of the parish Józefa and Nikodem from 1769. This cemetery could have been founded in the 17th century by the Jesuits (just like in Pióromont), and after their dissolution in 1773, taken over by the missionaries who in 1800 joined him with the parish church of St. Józef and Nikodem, and enlarged and merged.

This indicates the multi-stage development of the Ross cemetery and the connection of the Rosickis name with the name Rossa or Rosa. Formally, however, the Ross cemetery was established as a place of common burials of the dead residents of Vilnius only in 1769. Before that, the largest burial place was a large cemetery next to the now existing church of St. Józef and Nikodem for the Gate of Dawn.

The developing city in the second half of the eighteenth century more and more approximated its buildings to the church of St. Józef and Nikodem, also occupying fragments of the cemetery area. For these reasons, the then mayor of Vilnius, Basil Müller, in 1769 appointed a small area for the parish to the cemetery in the Rossa valley. The date of the beginning of the Ross cemetery is given by Adam Honory Kirkor, and later by Władysław Zahorski, Juliusz Kłos and others.

It is not known exactly how big this area was and what cemetery equipment was created on it, because no relics from this period have been preserved. Most probably, it was a non-fenced area in the central part of the present cemetery (in the area of the cemetery chapel) with tombstones in the form of earth graves and wooden crosses.

So far, it has been thought, however, recent observations of the area in front of the cemetery chapel have brought some observations, allowing for the emergence of a new hypothesis about the then development of the cemetery, which may be fully confirmed in the necessary field research.

Within the steep escarpment, between the terrace on which the cemetery chapel and the Main Avenue running along the fence wall, the difference in levels is about 2.5 m. It seems that this scarp was used in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. for family tombs, it is a remnant of a building. This is indicated by the remains of crypts and fragments of unidentified walls that can be seen above the ground and at a depth of 20-30 cm at some points of the slope near the surface of the lower alley.

On this basis, it can be assumed that in this place, the fifth (counting together and first in the order) wing of the columbarium was rising. Its construction can be associated only with the establishment of the Holy Graveyard here. Józef and Nikodem in 1769. It is difficult to imagine that a new parish cemetery, without the possibility of traditional burials in the "dungeon", could be accepted by the then urban society. Probably so, on the upland of the present terrace, a cross was erected, and on the slope along the old road to Rybiszki (Rossa street) a longitudinal columbar building was built, using the difference in levels. It was directed with an elevation with inscriptions towards the road, just behind a possible wooden fence. It is not known (without more detailed field research), what size it had, probably had at least three storeys of caverns having a length corresponding to the distance between the later, wings of the columbarium and created from a distance a building crowned with the aforementioned cross on the terrace.

Its early construction can be explained by the disappearance even before the middle of the 19th century, as well as by the layout of the later columbarium, for which it could be the beginning of spatial composition.

After erasing in 1799 the parish of St. Józef and Nikodem and joining it to the Church of the Ascension of the Lord (at Subocz Street), the cemetery in Rossa was taken in 1800 by missionaries who, after closing the old cemetery at the church of St. Józef and Nikodem applied to the authorities to enlarge and legalize the new cemetery.

The preserved documents concern only this stage of the cemetery's history. They show that on April 20, 1801, the Vilnius municipality, at the request of Fr. Tymoteusz Raczyński, parish priest of the Church of the Ascension of the Lord, agreed to the location of the cemetery in the suburb of Ross, by the road from Popław to Rybiszki. On May 1, 1801, the new cemetery was dedicated, and on May 8, the Mayor of Vilnius, Jan Müller, was buried there. In an official document from July 20, 1801, the Vilnius municipality confirmed the transfer of the municipal land with an area of 16 ropes and 16 square bars (ie 3.51 ha) to the parish. This concerned the southern and middle part of today's cemetery with the present chapel, covering the area from 1690 and 1769, enlarged by an additional one, given in 1801, which together were surrounded by a wooden fence. The oldest tombstones from the second decade of the 19th century have survived in this area. The second entrance gate (now bricked up) from Rossa street may be located near the former entrance to this old cemetery. The wooden fence was demolished in 1812 and consumed by the soldiers of the retreating Great Army of Napoleon.

In 1814, the cemetery was enlarged by a northern part with a later Hill of Writers and with the North Valley bought from Rozalia Sutocka. The entire area of 6.2 ha was surrounded by a brick fence, with arched recesses from the inside and a gate completed in 1820. At that time a hospital house for the poor was erected, the remnant of which is probably a one-story stone part of the caretaker's cottage with a wooden floor built in 1882. , says the date written on the tympanum of this building.

The plan for the cemetery at Rossa, or at least its central part, showing the features of the Baroque-Classical composition, is probably the work of Józef Poussier (+ 6 August 1821), the then Vilnius province governor.

In the years 1802-1807 were built two complexes of great stone columbaria located symmetrically (to the existing old?) On the central hill, the oldest part of the cemetery. The location of the colonnades on both sides of the later (1841) brick cemetery chapel indicates the possible existence of an older building of this function on its place, and the wooden tower, replaced in 1888, was probably its last remnant. Such an object on the cemetery far away from the parish church was indispensable. Was it a wooden or perhaps a brick classicistic building on the plan of an ellipse creating an interior not very suitable in the neo-Gothic architecture of the current building - it is not known. It can be assumed, however, that a provisional cemetery chapel may have been established not later than columbaria, and a new one was erected in its place after the destruction or wear of the old one.

The construction of a new brick cemetery chapel began in 1841 at the initiative of priest. Józef Bohdanowicz, the last visitator of missionary priests, and was completed in 1850 by a university professor.

The architecture of the facade of the tower refers exactly to the architecture of the chapel and contains motifs copied almost from the facade of the Bernardyński church. They show a slightly greater perfection of workmanship and the use of sandstone and a brick face instead of plaster, which indicates the red-white (gray) colors of the old façades. This is indicated by a plaque embedded in the eastern wall of this tower-belfry. There was an old bell from 1605, moved here at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries from the church of St. Michał, whose history was described by Michał Brensztejn.

The walls of the fence, quite weak and running along hills and slopes, have been repaired many times, and to this day they have been preserved in their former form from the northern and partly western sides. From this last page, around the middle of the 19th century, two gates were built - the old one (now bricked up) and the main one from the city side.

The main one, built in pseudo-Gothic forms (along with the construction of the Jeleński chapel?), Was given in the 1930s as white pillars with pilasters topped with hipped roofs with wrought-iron roofs with wrought decorative Vilnius crosses at the top. Similarly forged iron were gate and gate wings. In the years 1990-1991, this gate has been restored to its former pseudo-Gothic form (it is not known for what?).

The process of building the necessary equipment of the then largest Catholic cemetery in Vilnius, initially known as Missionary or Ruda, and after the liquidation of the monastery in 1845 only by Rossa, ended.

At the same time, and especially from the mid-19th century, apart from a growing number of burials and tombstones, numerous tomb and classical chapels were created, the oldest of them - the Kashyce chapel from around the mid-nineteenth century, and mostly in the spirit of historicism architecture from the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. These include the pseudo-Gothic chapel of the Jeleńskis, located right next to the entrance gate, eclectic chapels of Żyliński and Vileisis, Art Nouveau Chądzyńskich and the tomb of Gimbutt, neo-Renaissance Mączyńskis, modest neoclassical Wańkowicz from Petesze, Pietkiewicz, Plater and others. In addition to the chapels, several religious tombs were created in the form of colums, such as business cards, and family in various forms.

It soon became necessary to extend the area of the cemetery, which was needed for an increasing number of burials in the developing city. The hills adjacent to the eastern side were used for this purpose. In the Russian monastery O.O, occupied by the Russian authorities The missionaries organized a branch of a military hospital (the main hospital was in the Sapieha palace in Antokol), which sought a place for the burial on Ross, and in 1847 began to bury the dead soldiers and poor city residents outside the official cemetery on the opposite hillside, separated from the old cemetery a road in the valley (Listopadowa St.). In this cemetery, initially "orphan", they were later buried, among others soldiers of Vilnius Self-Defense from 1919 and Polish and Lithuanian soldiers died in 1920. Even in the 1920s, the area of this cemetery was not fenced and without trees, and only in the 1930s was it organized and fenced (area approx. 4.6 ha), receiving the name Nowa Rossa.

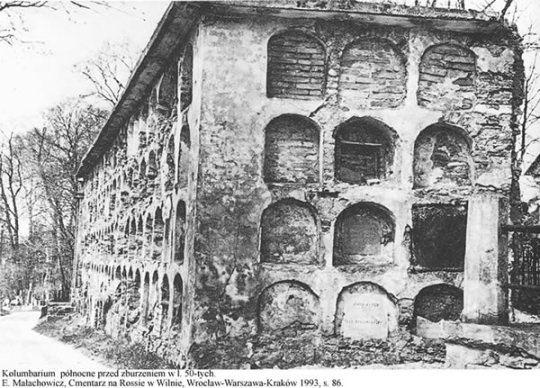

The second major cemetery of Polish soldiers who died in 1919-1920 was established in front of the main gate, and in 1926 it was rebuilt according to the design of architect Juliusz Kłos. In turn, in 1936, it was rebuilt and enlarged, and a urn with the heart of Marshal Józef Piłsudski and his mother's ashes under a large basalt slab were placed inside. Despite the burial-related efforts to maintain order in the 1930s, as the cemetery grew obsolete, the process of its destruction began. In the absence of sufficient care on the part of the user (from 1845, parish church of St. John), the technical condition deteriorated kolumbariów. Although the decades of the 20th and 30th centuries of our century were buried in the free niches of the columbaria, in 1936 the southern part of the columbarium (further from the main gate) was hurriedly demolished. The remains from the niches were buried in two mass graves. Those whose boards have been preserved - by the southern wall of the chapel near the tombstone of Fr. Józef Bowkiewicz, at some of the tables, eg Władysław Horodyski (1885 - 1920) and Tomasz Husaszewski (1732-1807), moved to the free niches of the second columbarium, and deprived of plaques - east of the chapel in the valley behind the tomb of Iza Salmonowiczówna.

During the construction of the cemetery-mausoleum in 1936 and cleaning works, adjacent hills, and especially between Rossa street and the Lida route, were bought by the City Board and intended for the "buffer zone" of the cemetery's landscape park. Thanks to this, they have not been built up to this day and the landscape of this magnificent park and cemetery complex has not suffered in this area. Small damage to the tombstones, mainly the military cemetery, brought an ongoing battle cemetery in 1944, but the greatest devastations arose later. The most painful of them was the destruction of the other columbaria in the 1950s and (with a great deal of piety) removal of remains and tombstones.

The Ross cemetery, closed since 1967 (with the exception of the burials of meritorious people), was officially recognized in 1969 as a cultural monument (of "republican" meaning, ie Lithuania) and covered by care. Clean up work was only undertaken in 1988 in connection with the dispute over limiting the scope of (?) Building a wide communication artery between Stara and Nowa Rosa. It threatened to destroy many historical graves and aroused a wide social protest; caused the development of the "reconstruction" project, ie the reconstruction of the cemetery.

For this purpose, the date of May 15, 1989 was used to organize (by the families of the deceased) abandoned and neglected graves, which was to force, necessary according to designers, cleaning work on the graves of buried persons and allow other work. The most important change is to be the construction of a new main entrance from the side of the new communication artery (former Listopadowa street) near the cemetery of Lithuanian and Polish soldiers, with driveway and parking lots. This is to expose, part of the cemetery of the majority of Lithuanian tombstones, leaving the old entrance with the cemetery-mausoleum of Polish soldiers somewhat in shadow.

This concept should not raise any objections, but rather it may favor the protection of the oldest part of the cemetery (at Rossa Street) from excessive traffic. Only the range of demolitions can be different, because the number of tombstones recognized as monuments.

Edmund Małachowicz

#cemetery#cmentarz#cmentarz rossie#lithuania#vilnius#ross cemetery#cemetry#cimitero#cimetiere#taphophile#taphophilia#memento mori#ossuary#black and white#in memoriam#rip#death#coemeterium#post mortem#sepulcher#bw#stone#tombstone#headstone#gravestone#graveyard#burial ground#burial#europe#gothic place

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jesienią, częściej niż w innych porach roku, wspominamy naszych bliskich zmarłych i częściej odwiedzamy ich groby. O tej porze roku przypada też Dzień Zaduszny, w różnych kościołach chrześcijańskich związany z liturgią poświęconą zmarłym. Zresztą różne ludy pogańskie zamieszkujące niegdyś Europę także jesienią celebrowały obrzędy ku czci zmarłych.

W nawiązaniu do tego tematu, z pewnym wyprzedzeniem postanowiłam przedstawić dzieje oliwskiego cmentarza oraz zwrócić uwagę na zasłużonych gdańszczan, którzy tam spoczęli.

Zapewne wielu z nas odwiedza tam groby swoich krewnych i znajomych. Jednak nie każdy wie, jakie były początki tej gdańskiej nekropolii.

Charakterystyczna kapliczka znajdująca się przy jednej z alei na cmentarzu oliwskim

Obecnie jest to cmentarz komunalny nr 2 w Gdańsku. Jego krawędź południowa biegnie wzdłuż ul. Opackiej, zachodnia wzdłuż ul. Czyżewskiego, zaś północna i częściowo wschodnia graniczy z terenem zajmowanym przez Telewizję Gdańską. Cmentarz ten obecnie zajmuje powierzchnię 4,99 ha. Jego historia jest tym bardziej ciekawa, gdyż z punktu widzenia historycznego składa się on z czterech cmentarzy (piąty po drugiej wojnie światowej został zlikwidowany; pewną jego część zajmują budynki należące do Telewizji).

Kościół św. Jakuba z przyległym do niego dawnym cmentarzem

Zacznę od tego, że najstarszy cmentarz oliwski znajdował się na terenie otaczającym kościół św. Jakuba; pierwsza wzmianka na jego temat pochodzi z 1308 r. i dotyczy decyzji opata Rudigera o pochowaniu na tym terenie ofiar dokonanego przez Krzyżaków pogromu zwanego rzezią Gdańska lub „krwawym Dominikiem” – jak to określił prof. Jerzy Samp. Zdarzenia te miały to miejsce w listopadzie 1308 r.

Cmentarz ten był wykorzystywany do pochówków do 1832 r. Jak wspomina Franciszek Mamuszka w swej publikacji pt. „Oliwa okruchy z dziejów, zabytki”, nieliczne kamienne nagrobki dotrwały do początku lat sześćdziesiątych XX w. Były to: klasycystyczny nagrobek z 1766 r., płyta nagrobna z 1832 r., stojące obok niej słupki z 1729 r. oraz nagrobek z 1788 r. Zlikwidowano je podczas rewaloryzacji kościoła św. Jakuba.

Pozostałość dawnej fontanny na terenie dawnego cmentarza ewangelickiego (ob. w obrębie cmentarza komunalnego nr. 2)

W latach trzydziestych XIX w. oliwski kościół św. Jakuba został przekazany protestantom; funkcję świątyni parafialnej dla katolików przejął kościół pocysterski pod wezwaniem św. Trójcy (w związku z kasatą zakonu cystersów zarządzoną przez władze pruskie).

Katolikom przyznano – jako miejsce pochówku swoich zmarłych – teren wielkości dwóch mórg kształtem zbliżony do prostokąta, rozciągającego się ze wschodu na zachód, krótszym bokiem sięgający ob. ul. Czyżewskiego (przed wojną Ludolfiner Straße), przy której znajdowała się (i znajduje się nadal) brama. Dziś jedna z czterech w ogrodzeniu cmentarza przy tej ulicy. Na południe od niej wybudowano z polecenia proboszcza Schrötera – podaję za Franciszkiem Mamuszką – neobarokową kaplicę projektu architekta Sinlera z 1909 r., wybudowaną przez firmę Klawikowski za 8573 marek (poświęcona w 1910 r.). Kaplica ta pełni swą funkcję do dziś. Główna aleja tego cmentarza biegła od wspomnianej bramy do krzyża umieszczonego przy wschodniej krawędzi cmentarza. Cmentarz ten określano wówczas mianem Katholischer Friedhof , czyli „cmentarza katolickiego” (po utworzeniu na początku XX w. drugiej nekropolii dla katolików, dodano „jedynkę rzymską”: Katholischer Friedhof I).

Kaplica proj. Sinlera, czynna do dziś

W podobnym czasie ewangelicy zaczęli grzebać swych zmarłych na terenie sąsiadującym od północy z cmentarzem katolickim. Podobnie jak cmentarz katolicki – ten także miał kształt prostokąta rozciągającego się się ze wschodu na zachód. Tak powstał Evangelischer Friedhof I. Obecnie stanowi on wewnętrzną część obecnego cmentarza.Przy zachodniej krawędzi tego cmentarza wybudowano niewielką kaplicę, która istnieje do dziś, jednakże jest nieczynna.

W pierwszej połowie XX w. oba cmentarze były już zapełnione. Dlatego ok. 1920 r. zarówno katolicy, jak protestanci otrzymali działki w sąsiedniej okolicy, by móc na nich grzebać swoich zmarłych.

Nieczynna kaplica cmentarna

Tzw. Evangelischer Friedhof II, czyli ewangelicki II powstał na terenie sąsiadującym od południa z katolickim I. W połowie długości głównej alei biegnącej z zachodu na wschód znajduje się do dziś nieduży plac z pozostałością dawnej fontanny pochodzącej z dwudziestolecia międzywojennego. Teren ten stanowi część obecnego cmentarza, wysuniętą najbardziej na południe, graniczącą z ul. Opacką.

Cmentarz katolicki II (Katholischer Friedhof II) powstał na terenie przyległym od północy do cmentarza ewangelickiego I. Jego główna aleja też biegnie od zachodu na wschód – do drewnianego krzyża.

Po północnej stronie całego założenia utworzono cmentarz bezwyznaniowy – tzw. Kommunalfriedhof. Powstał w 1921 r. na wniosek naczelnika Powiatu Gdańsk–Wyżyny dla innowierców. Zajmował działkę o kształcie trójkąta. Po wojnie został zlikwidowany. Jak już wspomniałam, na części tego terenu wybudowano obecną siedzibę Telewizji Gdańskiej.

Teren dawnego cmentarza dla innowierców zajmowany częściowo przez Telewizję Gdańską.

W poszczególnych częściach oliwskiej nekropolii przetrwały nieliczne nagrobki z przełomu XIX i XX w., w tym grób Antoniego Pikarskiego (weterana Powstania Styczniowego) i żony Amelii. Niestety większość dawnych grobów w okresie powojennym zlikwidowano, w tym – jak podaje Franciszek Mamuszka „cenny artystycznie pomnik w kształcie kolumny wykonany z piaskowca upamiętniający grób Józefa Gruchały–Węsierskiego, działacza polskiego pod zaborem pruskim”.

Grób weterana Powstania Styczniowego, Antoniego Pikarskiego i jego żony Amelii

Po wojnie spoczęło tu wielu gdańszczan zasłużonych dla miasta: Franciszek Mamuszka – popularyzator historii Gdańska i Pomorza, autor licznych przewodników (1905 – 1995); Jan Kilarski (1882 – 1951) – pochodzący ze Lwowa pedagog, krajoznawca, publicysta; prof. Marian Osiński – architekt, twórca gdańskiej powojennej szkoły architektów; prof. Kazimierz Kopecki (1904 – 1984) naukowiec, pracownik Politechniki Gdańskiej, dr Jan Szwarc (1901 – 1988) – psycholog, pedagog, organizator i dyrektor gdańskiego Państwowego Pedagogium; Zdzisław Kałędkiewicz (1913 – 2005) – artysta malarz i pedagog; prof. Bogusław Drewniak (1927 – 2017) historyk; Stanisław Chlebowski (1890 – 1969) – niegdyś bardzo ceniony artysta malarz, przedwojenny mieszkaniec Gdańska.

Grób Jana Kilarskiego

Grób Franciszka Mamuszki

Grób prof. Kazimierza Kopeckiego

Wśród pochowanych tu duchownych na uwagę zasługuje ks. Magnus Bruski (1886 – 1945) – prałat gdańskiej parafii katedralnej w latach 1926 – 35, przeciwnik ideologii nazistowskiej, zmarły na tyfus w lipcu 1945 r.

Niektóre pomniki nagrobne wyróżniają się wyszukaną formą. Ozdobione są rzeźbami lub płaskorzeźbami – wykonanymi w kamieniu lub drewnie. Warto zwrócić na nie uwagę podczas odwiedzin grobów naszych bliskich.

W ostatnich latach na cmentarzu oliwskim pojawiły się kolumbaria. Tam znajduje się m. in. miejsce upamiętnienia prof. Bogusława Drewniaka z Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego.

Pisząc ten artykuł korzystałam z następujących źródeł: “Encyklopedia Gdańska”, “Miasto tysiąca tajemnic” – prof. Jerzego Sampa oraz „Oliwa okruchy z dziejów, zabytki” – Franciszka Mamuszki.

Maria Sadurska

Uzupełniam ten artykuł swoją kolekcją zdjęć. Najpierw plan z wszystkimi aktualnymi wejściami na cmentarz oraz plan z 1935 r.

Cmentarz Oliwski – plan, cmentarze-gdanskie.pl

Cmentarz Oliwski – plan z 1935 r

Evangelischer Friedhof I – Cmenatrz Ewangelicki I

Cmentarz Ewangelicki I

Cmentarz Ewangelicki I, brama

Cmentarz Ewangelicki I, kaplica

grobowiec Chlebowskich

Katholischer Friedhof I – Cmentarz Katolicki I

Cmentarz Ewangelicki I, brama

Katholischer Friedhof I

Katholischer Friedhof I

Grób ks. Magnusa Bruskiego

Katholischer Friedhof I, brama

Katholischer Friedhof I, grób J. Stankiewicza

Katholischer Friedhof I, kaplica

Katholischer Friedhof I, ogrodzenie

Evangelischer Friedhof II – Cmentarz Ewangelicki II

Evangelischer Friedhof II, ogrodzenie

grób ojców cystersów

Evangelischer Friedhof II, brama

Evangelischer Friedhof II, brama

Evangelischer Friedhof II

Katholischer Friedhof II – Cmentarz Katolicki II

Cmentarz Katolicki II, brama

Cmentarz Katolicki II

Cmentarz Katolicki II, ogrodzenie

Cmentarz Katolicki II, brama

Usytuowanie grobu można znaleźć na dawnej stronie szukajgrobu.pl.

Anna Pisarska-Umańska

[mappress mapid=”627″ width=90%]

Oliwska nekropolia Jesienią, częściej niż w innych porach roku, wspominamy naszych bliskich zmarłych i częściej odwiedzamy ich groby. O tej porze roku przypada też Dzień Zaduszny, w różnych kościołach chrześcijańskich związany z liturgią poświęconą zmarłym.

0 notes

Link

Cmentarz parafii św. Katarzyny przy ul. Wałbrzyskiej, to obok tak zwanej Łączki na Powązkach oraz Cmentarza Bródnowskiego to największe pole grzebalne ofiar komunizmu w Polsce. IPN szacuje, że w latach 1946-1948 pochowano tu nawet tysiąc osób. Na cmentarzu rozszerzonym o działkę należącą przedtem do Józefa Bokusa oraz nieokreślone bliżej miejsca na Służewie nad Dolinką i ogólnie w parafii św. Katarzyny, to miejsca gdzie do połowy 1948 r. powi...

0 notes

Text

Akcja "Znajdź Bohatera"-sierżant Józef Szmyt i wachmistrz Hubert Staniowski

Akcja “Znajdź Bohatera”-sierżant Józef Szmyt i wachmistrz Hubert Staniowski

Kolejne dwa groby Polskich Weteranów spoczywających na porzuconym cmentarzu w Manchesterze zostały zarejestrowane w Instytucie Pamięci Narodowej jako “groby weteranów walk o wolność i niepodległość Polski” (zgodnie z ustawą z 2018 roku).

To zaledwie 4 zarejestrowane groby Polskich Weteranów na cmentarzu St.Joseph’s Moston w Manchesterze a w tym trzy z oficjalna tabliczką świadczącą o…

View On WordPress

#303#303 Productions#Armia Krajowa#Bohaterowie#Cmentarz Św. Józefa#Groby Polskich Żołnierzy#Hubert Staniowski#II Korpus Armii Andersa#Instytut Pamięci Narodowej#IPN#Izabela Gogol#Józef Szmyt#Karol Kamil Peruta Mikroblog#Karol Peruta#Konsulat Generalny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w Manchester#Konsulat Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w Manchesterze#Krzysztof Kopacz#Nie-patrioci UK#Ocalić od zapomnienia#Peruta#Peruta Manchester#Polacy w Angli#Polacy w Manchester#Polacy w UK#Polacy w Wielkiej Brytanii#Polish Centre Wilno Manchester#Polonia#Polonia w Anglii#Polonia w Manchester#Polonia w UK

0 notes

Text

30.10.2021 ZAPAL ZNICZ BOHATEROM - MANCHESTER

30.10.2021 ZAPAL ZNICZ BOHATEROM – MANCHESTER

Jest w Manchesterze miejsce smutne, porzucone i zapomniane, miejsce niechciane… Miejsce które już dawno temu zostało wymazane z polonijnej mapy Wielkiej Brytanii. Miejsce w którym wszystko się zaczęło, miejsce początku i w pewnym rodzaju końca powojennej Polonii w Manchesterze.

Tym miejscem jest cmentarz St.Joseph’s Moston na którym spoczywają Polscy Weterani a w większości w porzuconych i…

View On WordPress

#Battle of britain#Cmentarz Św. Józefa#Grzegorz Serafin#II Korpus Polski#Karol Kamil Peruta#Karol Peruta#Manchester#Manchester upamiętnił Bohaterów#Manchester Wielka Brytania#Ocalić od zapomnienia#Peruta#Pierwsza Samodzielna brygada Spadochronowa#Polacy w Angli#Polacy w Manchester#Polacy w UK#Polacy w Wielkiej Brytanii#Polonia#Polonia w Manchester#Polonia w UK#Polscy piloci#Polscy Weterani#Polski czerwony Krzyż#Porzucony cmentarz Polskich Weteranów#Powojenna Polonia Manchesteru#Powojenna Polonia w Manchesterze#St.Joseph&039;s Moston#Wspólne zapalenie zniczy#Wszystkich Świętych#Zapomniany cmentarz Polskich weteranów Manchester

0 notes

Text

W roku 1930 powstał w Gdańsku projekt szlaku krajobrazowego przebiegającego wzgórzami Wrzeszcza, od Aniołków po Oliwę. Był to szeroki projekt, jednak udało się zrealizować tylko jego część. Miał to być tzw. zielony pas w formie ścieżki łączącej lasy oliwskie z zagospodarowanymi terenami pofortyfikacyjnymi śródmieścia, poprzez parkowo-leśne obszary Wrzeszcza (także przez cmentarz Srebrzysko). Odcinek od Królewskiego Wzgórza do Oliwy nigdy nie powstał, ale powstał odcinek od Aniołków do Królewskiego Wzgórza. Ścieżkę nazwano Langfuhrer Höhenweg – przymiotnik “wrzeszczański” dodano zapewne, by odróżnić od ulicy Höhenweg na Siedlcach (dzisiaj Zagórska).

Na poniższe mapki naniosłam w uproszczeniu kierunek LH.

Plan z roku 1912

Oczywiście, Höhenweg nie biegła tak prosto, musiała dopasować się do istniejących warunków geograficznych i zabudowań. Czasami wtapiała się w istniejące ulice. Rozpoczynała się w rejonie Schopenhauerweg (obecnie Mikołaja Kopernika), przy Miejskim Domu Strzelniczym Bürgerschützenhaus (budynek nie istnieje). Następnie wspinała się po Wroniej Górze, wpadała do ulicy Dębinki (Eichenallee), okalała szpital i przez ulicę Jarową i Sobieskiego (Schluchtweg i Königstaler Weg) kierowała się w stronę posiadłości Zachariusza Zappio i Zakładu dla Niewidomych. Stamtąd biegła ku Królewskiemu Wzgórzu i Jaśkowej Doliny.

Plan z 1925

Opracowanie projektu trwało dwa miesiące. Wytyczono ścieżkę, posadzono szpalery drzew i postawiono ławki wzdłuż całej długości. Otwarcia dokonano 4 czerwca 1930 r. Ponieważ Höhenweg doskonale jest widoczna na planie z 1933 r., pokusiłam się o przejście tym szlakiem. Miał on wynieść 3 km i podobno trasę można było pokonać w godzinę, jednak mi zajęło to 3 godziny i mocno się umęczyłam. Może dlatego, że musiałam szukać jej śladów, niektóre przejścia były zamknięte i musiałam się cofać.

Co można było zobaczyć wzdłuż całej trasy? Jak wygląda Höhenweg? Dzisiaj widoki z niej są niedostępne, niewiele zostało. Może trasa jest bardziej zaniedbana, nie ma ławek, ale warto porównać stary i obecny szlak. Dla miłośników starego Gdańska, tropiących ślady historii, jest to rzecz na pewno interesująca. Zdjęcia mogą być lekko nieaktualne, bowiem przemierzyłam Höhenweg 2 lata temu, ale zasadniczo nie powinno być dużych różnic.

Etap 1 – od Domku Myśliwskiego Bürgerschützenhaus do ulicy Dębinki Eichenallee

Na tym odcinku Höhenweg biegnie po Wroniej Górze. Na planie z 1933 widać, że na Górze powstało kilka odnóg. Moją wędrówkę rozpoczęłam więc od Zigankenberger Weg, czyli ulicy Giełguda.

Przed skrzyżowaniem z LH mijam po lewej stronie cmentarz św. Brygidy i św. Józefa. Widać założenie alejkowe. “Z powodu przepełnienia cmentarza przy Wielkiej Alei będzie się odtąd grzebać zmarłych na nowym cmentarzu przed Bramą Oliwską, z wyjątkiem grobów z rezerwacją”. Ten nowy cmentarz to właśnie ten, “przy drodze do Suchanina”. Czynny był już od 1904 r.. Zlikwidowano go w 1956. Ten cmentarz nie jest ujęty jako “cmentarz nieistniejący”. W ogóle go nie ma. Zapewne usłany jest grobami. Na końcu alejki znajduje się podstawa krzyża.

Za cmentarzem skręcam w prawo, w Höhenweg i ścieżka prowadzi mnie chyba do punktu widokowego, który dzisiaj żadnym punktem nie jest.

Widać jednak, że coś się tu działo. Są schody.

Można znaleźć w sieci pewne ujęcie z Höhenweg z 1938 z widokiem na wyspę Ostrów (Holm). Być może jest ono stąd? Teraz teren jest cały zarośnięty, ale widać, że wiele drzew jest młodziutkich.

Ruszam w kierunku skrzyżowania. Stamtąd mam trzy zejścia z Wroniej Góry. Jedno jest niedostępne i jest to te, które prowadzi na Dębową i Dębinki (jest zatarasowane przy ulicy budynkiem), drugie prowadzi na ulicę Wronią, a trzecie do Domku Myśliwskiego, czyli tam, gdzie rozpoczyna się szlak. Widok ze skrzyżowania bardzo piękny. Jakoś niedawno miasto otworzyło punkt widokowy w tym miejscu. Jak widać, był on tu od 90 lat i ja zdjęcie robiłam przed otwarciem.

Idę w kierunku Bürgerschützenhaus, żeby znaleźć początek całego założenia.

Tu jest początek Höhenweg – Bürgerschützenhaus. Domek stałby po stronie prawej. W głębi widać ulicę Kopernika.

Wracam do punktu widokowego i aby dostać się do Dębinki, muszę zejść do ulicy Wroniej.

Etap 2 – od Dębinki do placu Heinricha Ehlersa

O placu, a właściwie boisku sportowym, dowiedziałam się dopiero z okazji tej wycieczki. Ulica Dębinki spina ze sobą dwa odcinki. Wychodzę więc z Orzeszkowej i szukam wejścia gdzieś w okolicy Hoene-Wrońskiego. Po drodze mijam teren cegielni, która działała do 1945 r. i od której ulica Śniadeckich nazywała się Ziegelstraße.

Mijam również posiadłość Alberta Forstera, a właściwie dom służby.

I widzę już wejście na Höhenweg. To jest tam, gdzie widać samochód między drzewami.

Jeszcze rzut oka na historię bardziej współczesną, czyli sowieckie napisy na cegłówkach ogrodzenia willi przy Hoene-Wrońskiego..

…i wchodzę na Höhenweg. Zawsze mnie frapowało, co to za ścieżka w tak dziwnym miejscu.

Mijam schrony przeciwlotnicze, olbrzymie, stare drzewa, ale miejsca po boisku sportowym znaleźć nie mogę. Powinnam je obejść i wyjść na ulicę Smoluchowskiego. Jednak tracę orientację. Zapewne wyjść gdzieś stąd można, ale kierunek, który mnie interesuje, robi się mało czytelny i pozagradzany. Langfuhrer Höhenweg powinna minąć dawne boisko i wyskoczyć na Feldstraße (Smoluchowskiego). Jednak boisko okazuje się zajęte przez szpital.

Etap 3 – od Smoluchowskiego do dworu Zachariasza Zappio

Wracam tą samą drogą na Dębinki i kieruję się w stronę szpitala zakaźnego za stadionem Lechii.

Na dawnym przedwojennym Heinrich Ehlers Platz, boisku nazwanym od Heinricha Ehlersa, nadburmistrza Gdańska 1903-10, stoi dzisiaj Centrum Medycyny Inwazyjnej. Dlatego nie mogłam się dostać z drugiej strony – teren jest ogrodzony. Trudno powiedzieć, że był to stadion, raczej właśnie boisko. I były tu rozgrywane mecze. Musiało być dosyć ciasne, bo w 1927 r. nieopodal wybudowano stadion im. Jahna Kampfbahna, później przechrzczony na Alberta Forstera, czyli stadion Lechii.

Natomiast zarys Höhenweg można dojrzeć za medycznymi budynkami – daleko hen w głębi.

Wpadałaby do Smoluchowskiego gdzieś na końcu tego budynku.

Żeby znaleźć dalszy bieg ścieżki, trzeba zejść do ulicy Sobieskiego (Königstaler Weg). Idę więc ulicą Jarową (Schluchtweg) w dół do skrzyżowania z Wileńską.

A potem w prawo do tego miejsca:

Ta droga prowadzi do dworu Zachariasza Zappio (obecnie przedszkole) i do dawnego Zakładu dla Niewidomych (obecnie prywatna szkoła). Na mapie współczesnej nie ma żadnej nazwy, ale przecież jest to Langfuhrer Höhenweg i to z pięknie zachowanym fragmentem w okolicy stawów. Trudno mi sobie wyobrazić ludzi spacerujących tędy 90 lat temu. Teraz miejsce jest jakieś zapuszczone. Tylko bliżej przedszkola robi się ładnie.

Koło Zachariasza Zappio widać ładnie utrzymane założenie spacerowe, z widokiem na staw.

Etap 4 – od Zakładu dla Niewidomych do Królewskiego Wzgórza

Dalej już jest nieciekawie, mijam zakład (szkołę) i wchodzę między drzewa. Ścieżka robi się nieczytelna. Zaczyna być trochę strasznie.

Aż wchodzę na coś, co stanęło na miejscu Oberhof.

To Radiowo-Telewizyjny Ośrodek Nadawczy, wieża nazywa się Jaśkowa Kopa i została wybudowana w połowie lat 80.

Znane jest wcześniejsze zdjęcie ośrodka. Zdaje się, że z lat 70-tych (w głębi).

Sam Oberhof, który tu stał, po wojnie otrzymał nazwę Górzyna. Nazwa Oberhof znana jest od początku XIX wieku, ale zabudowania pojawiły się prawie 100 lat później. Tutaj postanawiam skończyć moje poszukiwania Höhenweg. Zgodnie z planem ścieżka prowadzi stąd na północ na Królewskie Wzgórze i kończy się tam definitywnie. Jednak zwyczajnie boję się zgubić i jestem zmęczona. Na pocieszenie zostaje mi stara pocztówka z Höhenweg, właśnie z okolic Królewskiego Wzgórza.

Anna Pisarska-Umańska

Höhenweg – zapomniany szlak krajobrazowy W roku 1930 powstał w Gdańsku projekt szlaku krajobrazowego przebiegającego wzgórzami Wrzeszcza, od Aniołków po Oliwę. Był to szeroki projekt, jednak udało się zrealizować tylko jego część.

0 notes

Text

Instytut Pamięci Narodowej Oddział w Gdańsku zaprasza na uroczystości i wydarzenia edukacyjne towarzyszące obchodom Narodowego Dnia Pamięci Żołnierzy Wyklętych.

Obchody Narodowego Dnia Pamięci Żołnierzy Wyklętych w Gdańsku organizuje „Koalicja Pamięci o Żołnierzach Niezłomnych”, powołana 21 października 2016 r., w 53. rocznicę śmierci ostatniego Żołnierza Niezłomnego Józefa Franczaka „Lalka”.

W jej skład wchodzą:

Instytut Pamięci Narodowej Oddział w Gdańsku

Bractwo Świętego Pawła

Bazylika św. Brygidy w Gdańsku

Fundacja „Tożsamość i Solidarność”

Stowarzyszenie Kibiców Lechii Gdańsk „Lwy Północy”

Stowarzyszenie Historyczne im. 5 Wileńskiej Brygady AK.

Przewodniczącym „Koalicji” jest naczelnik Oddziałowego Biura Edukacji Narodowej IPN w Gdańsku.

Program

26 lutego 2017 r. (niedziela) godzina 8.00

Bieg Tropem Wilczym (Park Nadmorski im. Ronalda Reagana, ul. Piastowska)

Zapraszamy do udziału w kolejnej edycji Biegu Tropem Wilczym w Gdańsku – wydarzeniu upamiętniającym bohaterstwo Żołnierzy Niezłomnych. Zawodnicy pobiegną na trasie 1963 m (symbolizującej rok śmierci ostatniego Żołnierza Niezłomnego – Józefa Franczaka „Lalka”) i 5 km.

Zapisy w dniu biegu dostępne będą w godzinach 8.00–9.30 w cenie 40 zł i 50 zł (jeśli będą wolne miejsca). Trwają zapisy elektroniczne. Szczegółowe informacje organizacyjne dostępne są na stronie wydarzenia.

https://www.facebook.com/events/156963648133733/

.

8.00 – początek wydarzenia, możliwość odbioru pakietów i ich zakupu

10.00 – start biegu na trasie 1963 m (limit czasowy – 30 minut)

10.45 – start biegu na trasie 5000 m

11.30 – uroczyste zakończenie wydarzenia wraz z koncertem

Organizatorami Biegu Wilczym Tropem w Gdańsku jest trójmiejski oddział Stowarzyszenia KoLiber i Klub Republikański Gdańsk.

Bieg Tropem Wilczym w Gdańsku został objęty Patronatem Honorowym przez Instytut Pamięci Narodowej Oddział w Gdańsku.

Gdańsk Strefa Prestiżu patronuje biegowi medialnie.

W 2016 roku tak wyglądał bieg Tropem Wilczym w Gdańsku.

26 lutego 2017 r. (niedziela) godzina 11.00

III Krajowa Defilada Pamięci Żołnierzy Niezłomnych (Bazylika św. Brygidy, ul. Profesorska 17 – ul. Długa)

11.00 – msza św. w bazylice św. Brygidy

12.30 – wymarsz defilady spod bazyliki

13.15 – uroczyste meldunki formacji rekonstrukcyjnych składane gen. Władysławowi Andersowi (ul. Długa)

13.45 – koncert pieśni partyzanckich w wykonaniu Męskiego Towarzystwa Śpiewaczego „Gryf”

27 lutego 2017 r. (poniedziałek), godz. 17.00 (siedziba IPN w Gdańsku, al. Grunwaldzka 216)

Wykład profesora Piotra Niwińskiego – Fenomen Żołnierzy Wykletych

Liczba miejsc ograniczona (decyduje kolejność wejścia na salę edukacyjną im. gen. Augusta Emila Fieldorfa „Nila”).

W trakcie wydarzenia otwarta będzie Księgarnia IPN z publikacjami o Żołnierzach Wyklętych.

1 marca 2017 r. (środa), godz. 7.00 (aleja Żołnierzy Wyklętych w Gdańsku, skrzyżowanie z ulicą Srebrniki)

Społeczna akcja zapalenia zniczy

1 marca 2017 r. (środa), godz. 19.00 (Cmentarz Garnizonowy w Gdańsku, ul. gen. Henryka Dąbrowskiego 2)

Uroczysty apel pamięci

3 marca 2017 r. (piątek), godz. 19.00 (Areszt Śledczy w Gdańsku, od strony ul. 3 Maja – Cmentarz Garnizonowy)

Droga Krzyżowa w intencji Żołnierzy Niezłomnych

Wydarzenia towarzyszące

24 lutego – 24 marca 2017 r. (ul. Grobla I)

Prezentacja wystawy za świętą sprawę – żołnierze Łupaszki

28 lutego – 24 marca 2017 r. (plac przy pomniku „Inki” w Gdańsku-Orunii, ul. Gościnna 15)

Prezentacja wystawy “Niezłomna wyklęta, przywrócona pamięci” Danuta Siedzikówna ‘Inka” 1928 – 1946

Pod siedzibą IPN oraz w czterech miejscach Gdańska zaprezentowane zostaną sylwetki “Niezłomnych”

https://www.facebook.com/events/1726044401058942/

.

Na wszystkie wydarzenia wstęp wolny. Zapraszamy.

Obchody Narodowego Dnia Pamięci Żołnierzy Wyklętych 2017 r. w Gdańsku zostały objęte Patronatem Honorowym Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Andrzeja Dudy.

Gdańsk Strefa Prestiżu

Obchody Narodowego Dnia Pamięci Żołnierzy Wyklętych – program Instytut Pamięci Narodowej Oddział w Gdańsku zaprasza na uroczystości i wydarzenia edukacyjne towarzyszące obchodom Narodowego Dnia Pamięci Żołnierzy Wyklętych.

0 notes