#Also what the hell why do they have so many similar design elements? I'd never even heard of Surge when I designed Sam.

Text

Punk lab rat girls with varying opinions on the oldies.

#I CAN DRAW ANYTHING I WANTTTTTT!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#Also what the hell why do they have so many similar design elements? I'd never even heard of Surge when I designed Sam.#Most of her design elements are inspired by Cloud Strife actually (different punk lab rat)#ophidian doodles#surge the tenrec#surge#unchained phenomena#samantha griffiths

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you said that when designing a character "its important to draw inspiration from real life sources instead of riding another designer's coattails. If you're using other animated characters as reference, you're doing it wrong.", I want to ask you a character design question:

I'm designing a character heavily inspired by Strickler from Trollhunters:

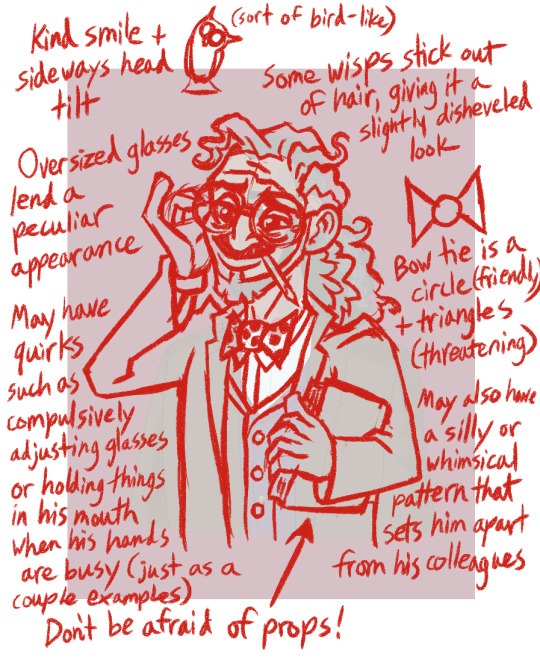

His name is Theodore Carter and he's also an antagonist and supernatural being disguised as a human high school teacher. His human form looks like this:

Similar to his inspiration he's also a tall, thin older gentleman with a prominent hooked nose and wearing a tweed costume. He's supposed to look friendly and dignified, yet slightly eccentric.

Do you have any criticism for my design? Does he look different enough from his inspiration and do you think it is possible to evoke the same feel as the character he was based on (a classy gentleman with a dark secret, can be friendly and charming one minute and threatening in another)?

I guess the first step would be to ask yourself how married you are to the similar elements. How important is it for this character to have a hooked nose, for example? What does it say about him? Does it tie into his personality, or perhaps hint at his supernatural form? (I'd guess a human disguise with an aquiline nose would represent an appropriately eagle-like creature, like a griffin or thereabouts.) Maleficent's horned headdress in Sleeping Beauty performs a similar function, foreshadowing her transformation into a dragon at the film's climax.

Also, why does he need to be a teacher? What narrative purpose does that serve? Is it to make him a mentor figure to children? Because that would still be the case if he were a librarian, a coach, a scout leader, etc etc. Hell, what if he were a parent of one of the school's students? What if he joined the PTA and volunteered as a chaperone for field trips? What if he were the cool dad all the kids liked, never suspecting for a second he was hiding something?

This is where you want to really interrogate your design choices. Ask yourself, "Why is this here?"

I could easily say there are no wrong answers to this question, but that'd be somewhat disingenuous. For our purposes, there are two answers that aren't wrong per se, but they're red flags that a design isn't as fleshed out as it could be.

Because [insert existing character here] has it

Because I think it looks cool [and that's the only reason]

Now. Caveats.

If you're including elements from an existing character as an homage to that character rather than a rip-off, that's... fine? Not ideal in my opinion (and I'll get to why in a bit), but fine. But what’s the difference between an homage and theft? Subtlety, usually. If your work includes a little shoutout to another work that only those aware of it would catch, that’s an homage. If it has so many obvious similarities with some other thing that it might as well BE the other thing with a different coat of paint, that’s a rip-off.

Here’s the problem with homages, though: If they aren’t subtle enough, you risk the audience thinking only of the other character when they see yours. You know how easy it can be to look at something while your mind wanders somewhere completely different? Same principle.

Zootopia handled homage well, using two illicit substance manufacturers named Walter and Jesse to make a Breaking Bad reference. But they were basically background characters with only a brief mention. Using a major character as an homage for another feels like a disservice to the character’s potential. Every main character we create deserves the chance to stick out in our audience’s memories rather than get sidelined by their original inspiration.

As for the “I think it looks cool” answer, a design element looking cool is a point in its favor (and hell, drawing aesthetically pleasing stuff is part of the fun), but if that’s all it has going for it, you might want to rethink it. It could look cool and serve a practical function (stylish glasses, for instance), employ visual symbolism, hold some sentimental value for the character, or some combination of the above, but simply looking cool on its own isn’t enough. (Also note that there’s a difference between aesthetics you like and aesthetics the character likes.)

Now let’s try to bring out more of this guy’s personality through the visuals. The “dignified” bit comes across fine, but the “friendly” and “eccentric” aspects could use more attention.

A little smile goes a long way when making a character look approachable, and a slight head tilt to the side is great for making them seem a bit “off”. It’s not so obvious as to immediately give away the twist, but it hints that there’s something about this guy other characters might want to keep an eye on. Then they’ll be able to tell if he’s the harmless kind of kooky or if there’s something more sinister afoot. And as usual, shape symbolism is a factor here.

I’ve talked about twist villains before, but to sum up: You’ll want to consider how the dude’s motivations affect his presentation (that is, the version of himself he shows to the outside world). How much of his true self does he reveal to others on a regular basis, and how much of it is an act? Where does he draw those lines, and how do these choices benefit him?

The “gentleman with a dark secret” has been done many times before. What matters is how you can do it differently.

Hope that helps!

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

I had a thought earlier and thought I'd shoot you an ask about it: Do you have any tips on getting better at world-building (I think you're great at it btw)? Also, have you always liked world-building, in itself? I find myself often using worlds other people create, because I'm not very good at creating/thinking of my own, and was wondering if that was lazy of me? Just was wondering what your opinion was, on all that! Just food for thought. c:

Thank you! I’m glad you think I’m good at it!

World-building is a very interesting subject, but it took me a while to even really appreciate what it was. I’ve also spent a lot of time in other people’s worlds and environments, that’s pretty common among fanfiction writers, but I wouldn’t consider it lazy. Not unless you think any fiction set in our world is also lazy. There will always be parts of a story that some people are better at or prefer to focus on, or still need to build up their skills at. It’s normal.

I think a few things are very key to good world-building, though. Or at least in my experience, it’s the stuff I’ve figured out that’s helped me the most.

1. Nothing is original. You might not be entirely sure of where an idea has come to you from, but at the end of the day, there are only so many facets to human existence out there. Our imaginations only carry us so far, and our ideas come from the people around us, and also from their ideas. Artists draw from the things they see and experience, and use references to make stuff more realistic. So do writers. Do not worry that your stuff is unoriginal. Doing your best to abandon that fear is one of the biggest favours you can do for yourself as a writer; there’s a difference between similar concepts and ideas, and plagiarism, and only plagiarism is really a problem.

2. Nothing is without real-world context. This is related to the above. The things you make are coming from somewhere, and that means that they will have implications and real-world parallels. It pays to stop and consider where you’re getting your ideas, and what those ideas are implying about the world around you, too. In order to write stories, you have to be willing to take the stuff of your daydreams, and hammer it out into a narrative. It’s like turning a hunk of rock into a gemstone. You have to cut pieces out, decide what to reshape, what to keep, and what to throw away. If you can’t attack your own presumptions about the real world, you’ll have a harder time shaping a consistent fictional one. But also, at the end of the day, a rough diamond and a faceted one are both still diamonds. People will often be able to tell where you’re pulling your ideas from, so what you say about certain subjects can still have an impact on real-world concepts, and on your readers.

3. Let your setting be bigger than you. When writing, it’s extremely easy to get caught up in your own ideals and frames of reference, and that can mean that you design a world that acts more like how you think it should, rather than how it would. Worlds are big, and to some extent you can mitigate this by being aware that there is more going on than what you’re describing - that your story’s perspective is limited to the characters and events in it, and that contradictory things or mysterious unknowns still linger in the wider scheme of the setting. Your characters shouldn’t know everything that you, the author, knows, and you, the author, shouldn’t know everything about the world, either. An exhaustive list of details can even work against you, because it makes it trickier to keep track of what all your characters do and don’t know as well.

4. Big events are great, but cause and effect is better. When you look at history, you can see the way certain figures and events impacted one another, and connected together to get people to their ends or beginnings. A common mistake in world building is to take the big events - wars, coronations, the fall of empires, the rise of them, etc, etc - and just throw them into the setting without much thought for how they all interact with one another. But it’s like… if you have a nation that’s got a standing army, that’s expensive. Most nations have very small armies of professional soldiers, and instead tend to temporarily conscript people to bulk up their armies in times of crisis, because someone who is busy training and fighting isn’t doing other vital work, like raising livestock or farming crops or building homes, making babies, running households, etc, etc. But they still need to be fed and clothed and offered some kind of shelter from the elements, provided with equipment and a certain degree of entertainment, and things like that. Professional soldiers can spend their time focusing on being the best fighters they can be, so there’s an advantage to it, but you also need to justify having them around, especially if the rest of your country is having to work overtime to keep them fed. So a nation with a big standing army is going to be a nation that finds a lot of reasons to go to war - war lets you bring home spoils, lets you raid someone else’s farms to feed your soldiers, and expand your territory, and tax or enslave conquered peoples, and so on and so forth. You can start your world-building at the point of ‘I want this nation to have a big army’, or you can start it at the point of ‘I want this nation to be war-like’, or somewhere else on the chain of events - but certain things will also imply certain other things. It’s best to be aware of what those elements are when you’re laying out your setting. If you make a nation with a big army that is ‘peaceful’, you either need to explain how that works, or else people will probably think that the reputation is inaccurate (and that’s fine, too, as along as you’re willing to create a nation with one hell of a propaganda machine instead). But if you have a warlike nation, then there will also be other nations that have taken the brunt of its actions and conquests. So you will do better to let a few key traits expand into their implications, than to try and railroad everything into a framework that doesn’t flow naturally from those things. Because if you have your big nation with its standing army and militant inclinations, every other part of the world is probably going to be impacted by its quest for expansion, and if they aren’t, you need to be thinking about why, or else the pieces of your setting won’t fit together very well.

5. Avoid the Golden Mean Fallacy. The Golden Mean Fallacy, also known as the ‘argument to moderation’, is the idea that the perfect solution to any problem lies in compromise. But thereare some situations where saying ‘both sides are in the wrong’ requires a lotof false equivalents or narrative contrivances, even though people often tend to think that this is the most reasonable or neutral stance to take as the sort of arbitrator of the setting. Approaching societal conflicts in your world-building withthe idea that compromise is an ideal solution can actually be really offensive, though, and less ‘neutral’ than beneficial to aggressive qualities in the setting.For example, if one group is trying to commit genocide against another, looking at it and going ‘okay you guys want to live, but these other guys want to killyou, so I think the solution here is to just let them eradicate your culture –that’s really what they’re objecting to, anyway, and then you get to live andthey still get to destroy you, everybody wins!’ is not something you want to present as a fair solution. Sometimes people are just plainly in the wrong. That said…

6. Nevermake any culture/race/ethnicity/etc ‘evil’ in your stories. Doesn’t matter ifit’s orcs, robots, aliens, faeries, or what-have-you. The ‘savage tribe ofmonster people’ or Always Chaotic Evil Race™ is a bad trope and it needs to godie in a fire. If you want an ‘evil group’, you will do far better to alignpeople based on something like ideology or political corruption than race, geography, or traits theyare born with. There are other tropes along these lines that should be avoided, too, in fact there are more of them than I could successfully list in a timely fashion. As a general rule, though, if taking your world-building principles and applying them to real-life groups would result in an appalling statement, you should either change it, or else work it in as a form of propaganda and prejudice which you’re well aware of. That’s the difference between something like ‘mages are the most dangerous people in Thedas’ versus ‘the Templars believe that mages are the most dangerous people in Thedas’. One is you, the writer, making a blanket statement that some groups of people are just born dangerous, whereas the other is you, the writer, creating a scenario where prejudice exists in the setting.

7. Taking something out is often harder than adding something in. For example, building a setting without something like sexism or racism is usually much more complex than building a setting with something like magic or dragons or something. Fantastical elements are flexible, and you can shift the rules of them around to suit your needs without too many people crying foul. Whereas something like sexism is built into a lot of aspects of our society, and sinks into things that many people don’t even think twice about. Trying to create a fictional world where there is no sexism or history of it is, therefore, very hard, because you have to learn as much as you can about the ways in which this prejudice impacts our society and our presumptions, and then try and extrapolate how that would change everyone’s behaviour in a different world. And what you don’t change will immediately tilt your setting towards being the kind of place where biased presumptions are true facts of nature, rather than being a place where bad attitudes merely exist among the people and cultures there. This applies to basically everything, by the way, although it’s usually the most glaring when someone decides that they don’t want to deal with X kind of bigotry, and think that just going ‘it doesn’t exist in this world’ is the simple way out. (It’s not, the simple way out is to go ‘it exists in this world just the same way it does in ours, but I’m not focusing on it’.)

8. Keeping track of things is more important than knowing them off the bat. Everybody knows you’re making stuff up. That’s what they came to this party for. Inconsistencies can happen, but it’s also entirely possible to get so caught up in the planning stage that you never actually do any writing. So a good compromise between spontaneous invention and consistency is to just note the things you add in when you add them in, and then figure out how they might impact the other elements in your story, and set aside potential consequences in case they’re interesting or useful later on. Editing is your friend, and ‘I don’t know, let’s think about it until I do’ is also a vital element to incorporate into your thinking.

9. Be aware that you can mess up, and probably will. In order for any story to be inclusive of a wide enough range of people and cultures to make a whole world, it’s going to require you stepping outside of your own experience, or incorporating stuff that you have only a limited amount of knowledge on. You may very well fuck this up. This doesn’t mean the attempt was doomed, and it doesn’t mean you’re bad at world-building, and it also doesn’t mean that you have to defend your mistake in order to keep your setting from being deemed a worthless heap of junk. Your honour doesn’t ride upon whether or not you can make a convincing argument as to why your intentions outweigh the unintended implications of your actions. If someone points out a mistake, you should think about the ways you can go about handling it and/or fixing it. Maybe you just suddenly made your virtuous heroic group a lot more shady than you thought. Maybe you have to abandon a plot twist you were originally angling for. Maybe you have to make your narrator a lot more unreliable than you initially planned. There are solutions, and most importantly, you gotta listen to the people in the real world whose cultures or traits you borrowed from for your story. Just like when you borrow anything. If it’s not yours, you need to respect that and be mindful of how you use it.

10. Have fun. When you make a new world, there should be things in it that you love. That speak to your delight and sense of wonder. These are the things that often help the most when you’re deciding what to actually make in your world. You want unicorns? Put in unicorns. You want talking dragons? Put in talking dragons. Just think about how they would work, and how people would react to them, and how having them around might change the way the world operates. A lot of stuff will build naturally out of that.

I hope some of this helps!

46 notes

·

View notes