#Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights

Text

Alabama Chief Justice Tom Parker, who wrote the concurring opinion in last week’s explosive Alabama Supreme Court ruling that frozen embryos have the same rights as living children, recently appeared on a show hosted by self-anointed “prophet” and QAnon conspiracy theorist.

Parker was the featured guest on “Someone You Should Know,” hosted by Johnny Enlow, a Christian nationalist influencer and devoted supporter of former President Donald Trump. Over the course of an 11-minute interview, Parker articulated a theocratic worldview at odds with a functioning, pluralistic society.

“God created government,” he told Enlow, adding that it’s “heartbreaking” that “we have let it go into the possession of others.”

Media Matters, the liberal media watchdog group, was the first to report on Parker’s appearance on the program.

That a state’s chief Supreme Court justice would associate himself with Enlow is a cause for alarm. Enlow is a prolific conspiracy theorist, often weaving QAnon apocrypha with prophecies he claims to receive directly from God.

As reported by Right Wing Watch, Enlow has claimed that Trump “is on assignment” from God to work with the angels Michael and Gabriel to take down George Soros and Bill Gates, among others; he has claimed that Russian President Vladamir Putin is fighting “Luciferian pedophiles” in Ukraine, in a battle to stop them from deploying vaccines and 5G that would turn people into transhumanist semi-robots; and he has claimed that the majority of other world leaders are “satanic” pedophiles who “steal blood” and “do sacrifices.”

Enlow’s interview with Parker was uploaded to Rumble, the alt-tech video platform, on the same day the Alabama Supreme Court issued its opinion that sent shockwaves throughout the reproductive rights community. The ruling, which makes fertility clinics liable in wrongful death lawsuits for harming or destroying an embryo, has already imperiled access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the state.

“Human life cannot be wrongfully destroyed without incurring the wrath of a holy God,” wrote Parker, a longtime anti-abortion advocate sometimes credited with building the legal framework to overturn Roe v. Wade. “Even before birth,” Parker added, “all human beings have the image of God, and their lives cannot be destroyed without effacing his glory.”

Parker used similar theological language in his interview with Enlow, thanking Enlow for promoting the “Seven Mountains” on his show. As HuffPost has reported before, the “Seven Mountains Mandate” is a doctrine at the core of the New Apostolic Reformation, an evangelical movement that believes in the supernatural, including the existence of modern-day apostles and prophets, and which is characterized by a belief in Christian dominionism. The Seven Mountains Mandate is the belief that Christians must conquer the “seven mountains” of societal influence — education, media, religion, family, business, entertainment and government — and force fundamentalist Christian values onto every part of American life, in order to pave the path for Christ’s return.

“As you’ve emphasized in the past, we’ve abandoned those Seven Mountains and they’ve been occupied by the opposite side,” Parker told Enlow, suggesting the chief justice is familiar with Enlow’s show. Enlow is a big proponent of the Seven Mountains Mandate, and maintains a far-right website with his wife called “Restore Seven.”

Parker also told Enlow that God is “equipping me with something for the very specific situation that I’m facing” as the Alabama chief justice.

Enlow, as noted by Media Matters, praised Parker and appeared mindful of not dragging the judge into even more controversial topics. He told Parker that he’s “in such a key place that we don’t want to have any conversations that hurt you in any kind of way, but we appreciate who you are, who you are in the kingdom.”

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

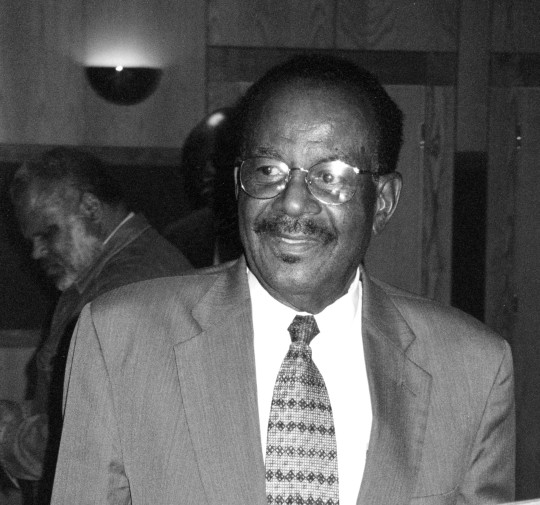

Judge Oscar William Adams, Jr. (February 7, 1925 – February 15, 1997) was the first African American Supreme Court Justice appointed in Alabama and when he stood for election to a full term, the first African American elected to a statewide constitutional office. He litigated many civil rights cases in his career as a lawyer and was part of the first African American law firm established in the state.

He was born in Birmingham to Oscar William Adams and Ella Virginia Adams; he was the older brother of Frank E. Adams. He graduated from Talladega College with a BA in Philosophy. He attended Howard University School of Law and graduated. He was admitted to the Alabama State Bar and began his legal career that would span five decades. He married Willa Ingersoll Adams (1949-82) and they had three children. He married Anne-Marie Bradford.

He litigated many civil rights and labor cases, and his clients included Martin Luther King Jr., the SCLC, Fred Shuttleworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, and the NAACP. The firm handled school desegregation and discrimination cases, as well as voting rights cases. Notable cases included Armstrong v. Birmingham Board of Education (1964), Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery (1969), and Pettway v. ACIPCO (1974).

On July 8, 1966, he became the first African American member of the Birmingham Bar Association. He ran his law office until 1967 when he went into practice with white attorney Harvey Burg, creating the state’s first integrated law practice. In 1969 he and James Baker became Adams and Baker Law Firm, were joined by U.W. Clemon, and the firm became known as Adams, Baker & Clemon.

He retired from the bench on October 31, 1993, after retirement, he worked with the Birmingham law firm of White, Dunn & Booker and served as co-chairman of the Second Citizens’ Conference on Judicial Elections and Campaigns.

He was inducted posthumously into the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame (2005) and the Birmingham Gallery of Distinguished Citizens (2008). #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lola Hendricks

Civil rights activist Lola Hendricks was born in 1932 in Birmingham, Alabama. Hendricks was Corresponding Secretary for the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, an organization founded after the NAACP was banned in Alabama. She organized protests and meetings, and was one of the parties to a set of lawsuits that ultimately led to the desegregation of Birmingham's public parks and city library.

Lola Hendricks died in 2013 at the age of 80.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christian conservative group opposes IVF for the most bizarre reason yet

The anti-LGBTQ+ group Family Research Council (FRC) opposes in vitro fertilization (IVF), a conception method responsible for roughly 2.3% of all infants born in the U.S. and often used by LGBTQ+ couples, because IVF clinics use pornography to get sperm from donors.

“Pornography is an integral part of the IVF process. And the husband’s use of pornography is typically how sperm was obtained. That’s not good for a marriage. We know that pornography goes against what God tells us about the dignity of men and women in a marriage,” said Mary Szoch, director of the FRC’s Center for Human Dignity (the FRC’s anti-abortion division), in a recent video.

Related

A couple’s fight over frozen embryos could upend IVF access in Texas

The case is no doubt part of the predicted “domino effect” stemming from the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling declaring embryos as legal children.

Married heterosexual couples who regularly view pornography report higher levels of relationship dissatisfaction and are more likely to get divorced, according to a 2020 study. However, the study couldn’t show which way the causation ran. That is, it’s not clear if porn causes relationship dissatisfaction or if dissatisfied partners are more likely to view porn.

LGBTQ+ news you can rely on

Keep track of the ongoing battle against bias and for equality with our newsletter.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

Of course, the FRC’s opposition to IVF is also shared by numerous Republican legislators who view fertilized embryos as living people and who view the discarding of such embryos as a form of murder. IVF, as it’s performed today, requires the creation of multiple fertilized embryos to increase the chances that at least one will lead to a pregnancy.

To date, three states — Missouri, Alabama, and Georgia — have laws that grant personhood to fertilized embryos. Arizona enacted a law granting those rights as well, but it’s currently blocked. A dozen other states have introduced legislation this year that would legally declare embryos as people.

IVF is also commonly used by same-sex couples to conceive children. As such, efforts to restrict IVF access particularly harm LGBTQ+ people who want to become parents.

Mary Szoch of the Family Research Council is really digging deep to rationalize the organization's opposition to IVF: "Pornography is an integral part of the IVF process … That's not good for a marriage." pic.twitter.com/DQKGr2sP5I— Right Wing Watch (@RightWingWatch) May 22, 2024

While the FRC describes itself as a church and, previously, as an educational non-profit, it’s foremost an anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-abortion organization, designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. It was founded in 1981 by James Dobson, a longtime homophobe who also founded Focus on the Family (FOF), the largest theocratic-right organization in the United States.

Both FOF and FRC oppose same-sex marriage and sex education in schools (except “abstinence-only”), support so-called conversion therapy, and generally oppose anything that promotes the so-called “homosexual agenda” — even concepts of tolerance and diversity which, according to Dobson, are “buzzwords for homosexual advocacy.”

According to Dobson, the goals of this homosexual movement include “universal acceptance of the gay lifestyle, the discrediting of Scriptures that condemn homosexuality, muzzling of the clergy and Christian media, granting special privileges and rights in the law, overturning laws prohibiting pedophilia, indoctrination of children and future generations through public education, and securing all the legal benefits of marriage for any two or more people who claim to have homosexual tendencies.”

Peter Sprigg, FRC’s Senior Researcher for Policy Studies, says that same-sex sexuality should be legislated and declared illegal and that “criminal sanctions against homosexual behavior” should be enforced. He also argued that repealing the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy encourages the… http://dlvr.it/T7Q6bQ

0 notes

Text

Anti-Science Trend Happening Within Conservative Movements

In the US, we are seeing the continuing power grab by extreme Christian Republicans in the recent IVF ruling by the Supreme Court of Alabama. This forms part of an anti-science trend happening within conservative movements, which first came to prominence during the Covid pandemic in America. People clinging to their beliefs in a Bronze Age God rather than following 21C scientific public health protocols. The GOP mined this protest against such things as vaccinations and mask wearing as grist for their politics of grievance. The US Supreme Courts discounting of Roe vs Wade has opened the door for more extreme demands by state based Republicans on the issue of women’s rights vs that of unborn foetuses.

“The Alabama Supreme Court has ruled that frozen embryos created and stored for in vitro fertilization (IVF) are children under a state law allowing parents to sue for wrongful death of their minor children.

The court, whose members are all elected Republicans or appointed by a Republican governor, further found that there was no "unwritten exception" for frozen embryos outside of a woman's uterus.

Chief Justice Tom Parker drew widespread attention for his overtly religious concurring opinion, in which he wrote that the state constitution includes the "theologically based view" that "human life cannot be wrongfully destroyed without incurring the wrath of a holy God." “

Photo by Ana Master on Pexels.com

Alabama Supreme Court Anti-Science Ruling Over IVF

Alabama was a slaver state and has a rich white supremacist history where African Americans have been disenfranchised from their voting rights for large periods of the 20C. The Republican Party there has been at the forefront of such misuses of power and gerrymandering to deliver control of the state to white GOP aligned folk. This overt concern with controlling women’s reproductive functions of American citizens in the 21C is yet another manifestation of authoritarianism. The warped rendition of Christianity which occurs in parts of America bears little to no relation to the life of Jesus Christ and the gospels. Christian Nationalism is about secular power and it has becoming increasingly authoritarian in recent years. Supreme Court justices talking about “the wrath of a holy God” does not augur well for a 21C progressive society. Rather, it is backward and a denial of the scientific reality of life in America in this day and age. A small coterie of wealthy and powerful people have stopped listening to the will of the people and seek to control their lives according to their own cultish interpretations of scriptures written thousands of years ago. I always find it interesting that right wing movements champion individual rights, unless you are a woman, and then the male dominated state owns your reproductive rights. Suddenly, government is OK in this instance and control is justified. Women are second class citizens in conservative America. Women run last under the auspices of these Christian Churches and cults.

Orion at White House for Made in America Product Showcase (NHQ201807230014) by NASA HQ PHOTO is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

Trump & The Religious Right

On the larger front, the Trump run for the Presidency is full of this anti-science trend happening within conservative movements. Steve Bannon and his cadres are hovering around Donald Trump threatening their religious extremism upon ordinary Americans. Personal freedoms are in the cross hairs of these God awful people. The Trump push is a coalition of corruption and Christian Nationalists. Greedy business leaders want to get their hands on more money by hook or by crook. Meanwhile, authoritarian religious movements want to see some real power back in the hands of those who profess concern for the soul of America. They want the state to own the reproductive rights of all women. IVF is an abomination in the eyes of many of these extremists. They want sexual freedoms rolled back by denying contraception access to Americans. They want a return to when religious leaders were in the bedrooms of America and controlling what went on there.

Photo by RF._.studio on Pexels.com

American Anti-Science Push Happening At GOP State Level

Can these autocratic Americans turn the clock back to a time when science kow towed to God? These authoritarians hate progressives so much that they want to see them locked up for being gay or LGBTQIA. They want marriage equality binned and only reserved for God fearing heterosexual Christians. Their white supremacist views truly believe in a blue eyed Jesus and an exclusive Christianity for their kind over others. Many of the Trump states are former slaver states and their warped version of Christianity maintained a love of God whilst enslaving other human beings. Science and rationality has long been the enemy of such folk. Which America will prevail to go into the future, a democratic progressive nation or a sick backward looking place full of inequality and division? Only time will tell.

“The ruling of Roe v. Wade meant that the right to abortion access in the first trimester was protected by the Constitution and could not be restricted by state or federal laws.”

- (https://unyouth.org.au/roe-v-wade-explained/#:~:text=TherulingofRoev,bystateorfederallaws.)

The US Supreme Court overturned this 50 year precedent in 2022 in Dobbs vs Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Stacking SCOTUS with conservative/Christian justices had been a 30 year campaign by GOP aligned forces.

Robert Sudha Hamilton

©MidasWord

Read the full article

#Alabama#anti-science#ChristianNationalism#conservatives#Covid#extremism#GOP#IVF#reproductiverights#Republicans#SupremeCourt#Trump

1 note

·

View note

Text

Current Recognized Party Labels

Welcome Page 2024 Party List

The following is a list of the abbreviations used to identify the party labels on various state ballots for the U.S. Presidential and Congressional candidates. The party label listed may not necessarily represent a political party organization.

*** If the party is no longer current it will be crossed out ***

AC = Agent of Change

ACE = Ace Party

ACP = American Congress Party

AE = Americans Elect

AIC = American Independent Conservative

AIP = American Independent

AKI = Alaskan Independence Party

ALP = American Labor Party

AMC = American Constitution Party

AMP = American Party

ANT = Action No Talk

APF = American People's Freedom Party

APP = Anti-Prohibition

ARM = American Renaissance Movement

BD = Be Determined

BHT = Bring Home Troops

BP = By Petition

CEN = Centrist Party

CFL = Connecticut for Lieberman

CGR = Coalition on Government Reform

CIT = Citizens' Party

CL = Citizen Legislator

CMD = Commandments Party

CMP = Commonwealth Party of the U.S.

CNC = Concerned Citizens Party of Connecticut

COM = Communist Party

CON = Constitution

COU = Country

CPA = Constitution Party of Alabama

CPF = Constitution Party of Florida

CPW = Constitution Party of Wisconsin

CRV = Conservative Party

D/C = Democratic/Conservative

DAC = Defend American Constitution

DCG = D.C. Statehood Green

DEM = Democratic

DFL = Democratic - Farmer - Labor

DGR = Desert Green Party

DNL = Democratic-Nonpartisan League

FA = For Americans

FED = Federalists

FLP = Freedom Labor Party

FRE = Freedom Party

FWP = Florida Whig Party

GBS = Gravity Buoyancy solution

GR = Green-Rainbow

GRE = Green

GRT = Grassroots

GTP = Green Tea Patriots

GWP = George Wallace party

HRP = Human Rights party

IAP = Independent American Party

ICC = Independent citizen for Constitutional Government

ICD = Independent Conservative Democratic

IDE = Independent Party of Delaware

IDP = Independence

IGD = Industrial Government Party

IGR = Independent Green

IND = Independent

INP = Independent Patriots

INW = Independent No War No Bailout

IP = Independent Party

IPR = Independent Progressive

JCN = Jewish/ Christian National

JNP = Jobs Now

JUS = Justice party

LAB = U.S. Labor Party (Also see LBR)

LB = Liberty

LBL = Liberal party

LBR = Labor party (Also see LAB)

LBU = Liberty Union Party

LFT = Less Federal Taxes

LIB = Libertarian

LRU = La Raza Unida (Also see RUP)

MLU = marklovett.us

MOD = Moderates

MTP = Mountain Party

N = Nonpartisan

NA = New Alliance

NAF = Non-Affiliated

NAP = Prohibition Party

NDP = National Democratic Party

NJC = New Jersey Conservative Party

NJT = NJ Tea Party

NLP = Natural law Party

NNE = None

NON = Non-Party

NOP = No Party Preference (Commonly used in CA & WA)

NP = Nominated by Petition

NPA = No Party Affiliation

NPP = New Progressive Party

OE = One Earth Party

OTH = Other

PAF = Peace and Freedom (Also see PFP)

PCH = Personal Choice Party

PFD = Peace Freedom Party

PFP = Peace and Freedom Party (Also see PAF)

PG = Pacific Green

POP = People Over Politics

PPD = Popular Democratic Party

PPY = People's Party

PRI = Puerto Rican Independence Party

PRO = Progressive

PSL = Party for Socialism and Liberation

PTF = Party Free

RDH = Rent is 2 Damn High

REF = Reform

REP = Republican

RES = Resource party

RTL = Right To Life

RUP = Raza Unida Party (Also see LRU)

SEP = Socialist Equality Party

SHE = S.H.E.R.O. Party

SLP = Socialist labor party

SOA = Socialist Action

SOC = Socialist Party U.S.A.

SUS = Socialist Party

SWP = Socialist Workers

TBE = The Blue Enigma Party

TEA = Tea party

TCH = Time For Change

TFC = Towne for Congress

THD = Theo- Democratic

TPN = Tea Party of Nevada

TRI = Tax Revolt Independent

TRP = Tax Revolt

TVH = Truth Vision Hope

TWR = Taxpayers Without Representation

TX = Taxpayers

UC = United Citizens

UN = Unaffiliated

UNI = United Party

UNK = Unkown

UPA = United Party of America

USM = United States Marijuana

USP = U.S. People's Party

UST = U.S. Taxpayers

VET = Veteran's Party

VPC = Vote People Change

W = Write-In

WF = Working Families

WG = Wisconsin Green

WTP = We The People

YCA = Your Country Again

Welcome Page

0 notes

Text

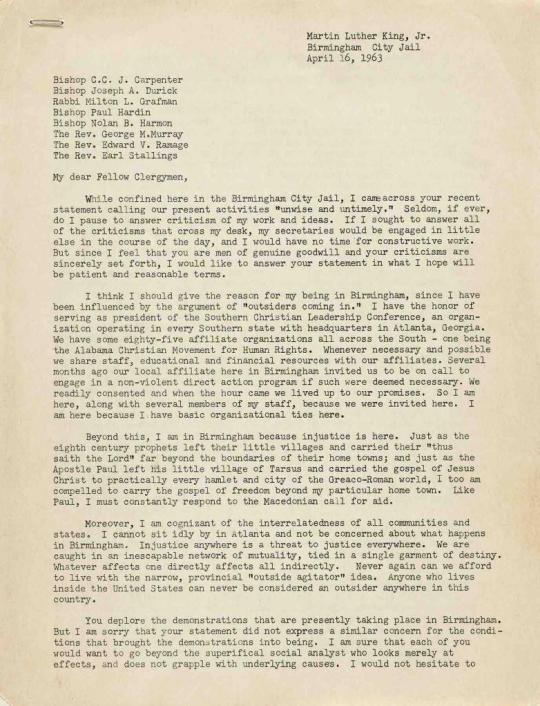

16 April, 1963

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.

I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in.” I have the honor of serving as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization operating in every southern state, with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. We have some eighty five affiliated organizations across the South, and one of them is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Frequently we share staff, educational and financial resources with our affiliates. Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.

In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good faith negotiation.

Then, last September, came the opportunity to talk with leaders of Birmingham’s economic community. In the course of the negotiations, certain promises were made by the merchants—for example, to remove the stores’ humiliating racial signs. On the basis of these promises, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the leaders of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights agreed to a moratorium on all demonstrations. As the weeks and months went by, we realized that we were the victims of a broken promise. A few signs, briefly removed, returned; the others remained.

As in so many past experiences, our hopes had been blasted, and the shadow of deep disappointment settled upon us. We had no alternative except to prepare for direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community. Mindful of the difficulties involved, we decided to undertake a process of self purification. We began a series of workshops on nonviolence, and we repeatedly asked ourselves: “Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?” “Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?” We decided to schedule our direct action program for the Easter season, realizing that except for Christmas, this is the main shopping period of the year. Knowing that a strong economic-withdrawal program would be the by product of direct action, we felt that this would be the best time to bring pressure to bear on the merchants for the needed change.

Then it occurred to us that Birmingham’s mayoral election was coming up in March, and we speedily decided to postpone action until after election day. When we discovered that the Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor, had piled up enough votes to be in the run off, we decided again to postpone action until the day after the run off so that the demonstrations could not be used to cloud the issues. Like many others, we waited to see Mr. Connor defeated, and to this end we endured postponement after postponement. Having aided in this community need, we felt that our direct action program could be delayed no longer.

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.

One of the basic points in your statement is that the action that I and my associates have taken in Birmingham is untimely. Some have asked: “Why didn’t you give the new city administration time to act?” The only answer that I can give to this query is that the new Birmingham administration must be prodded about as much as the outgoing one, before it will act. We are sadly mistaken if we feel that the election of Albert Boutwell as mayor will bring the millennium to Birmingham. While Mr. Boutwell is a much more gentle person than Mr. Connor, they are both segregationists, dedicated to maintenance of the status quo. I have hope that Mr. Boutwell will be reasonable enough to see the futility of massive resistance to desegregation. But he will not see this without pressure from devotees of civil rights. My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse and buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us consciously to break laws. One may well ask: “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.”

Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an “I it” relationship for an “I thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things. Hence segregation is not only politically, economically and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong and sinful. Paul Tillich has said that sin is separation. Is not segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness? Thus it is that I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court, for it is morally right; and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances, for they are morally wrong.

Let us consider a more concrete example of just and unjust laws. An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself. This is difference made legal. By the same token, a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow and that it is willing to follow itself. This is sameness made legal.

Let me give another explanation. A law is unjust if it is inflicted on a minority that, as a result of being denied the right to vote, had no part in enacting or devising the law. Who can say that the legislature of Alabama which set up that state’s segregation laws was democratically elected? Throughout Alabama all sorts of devious methods are used to prevent Negroes from becoming registered voters, and there are some counties in which, even though Negroes constitute a majority of the population, not a single Negro is registered. Can any law enacted under such circumstances be considered democratically structured?

Sometimes a law is just on its face and unjust in its application. For instance, I have been arrested on a charge of parading without a permit. Now, there is nothing wrong in having an ordinance which requires a permit for a parade. But such an ordinance becomes unjust when it is used to maintain segregation and to deny citizens the First-Amendment privilege of peaceful assembly and protest.

I hope you are able to see the distinction I am trying to point out. In no sense do I advocate evading or defying the law, as would the rabid segregationist. That would lead to anarchy. One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.

Of course, there is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience. It was evidenced sublimely in the refusal of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego to obey the laws of Nebuchadnezzar, on the ground that a higher moral law was at stake. It was practiced superbly by the early Christians, who were willing to face hungry lions and the excruciating pain of chopping blocks rather than submit to certain unjust laws of the Roman Empire. To a degree, academic freedom is a reality today because Socrates practiced civil disobedience. In our own nation, the Boston Tea Party represented a massive act of civil disobedience.

We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was “legal” and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was “illegal.” It was “illegal” to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany. Even so, I am sure that, had I lived in Germany at the time, I would have aided and comforted my Jewish brothers. If today I lived in a Communist country where certain principles dear to the Christian faith are suppressed, I would openly advocate disobeying that country’s antireligious laws.

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress. I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that the present tension in the South is a necessary phase of the transition from an obnoxious negative peace, in which the Negro passively accepted his unjust plight, to a substantive and positive peace, in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality. Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.

In your statement you assert that our actions, even though peaceful, must be condemned because they precipitate violence. But is this a logical assertion? Isn’t this like condemning a robbed man because his possession of money precipitated the evil act of robbery? Isn’t this like condemning Socrates because his unswerving commitment to truth and his philosophical inquiries precipitated the act by the misguided populace in which they made him drink hemlock? Isn’t this like condemning Jesus because his unique God consciousness and never ceasing devotion to God’s will precipitated the evil act of crucifixion? We must come to see that, as the federal courts have consistently affirmed, it is wrong to urge an individual to cease his efforts to gain his basic constitutional rights because the quest may precipitate violence. Society must protect the robbed and punish the robber.

I had also hoped that the white moderate would reject the myth concerning time in relation to the struggle for freedom. I have just received a letter from a white brother in Texas. He writes: “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but it is possible that you are in too great a religious hurry. It has taken Christianity almost two thousand years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” Such an attitude stems from a tragic misconception of time, from the strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually, time itself is neutral; it can be used either destructively or constructively. More and more I feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than have the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right. Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy and transform our pending national elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. Now is the time to lift our national policy from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of human dignity.

You speak of our activity in Birmingham as extreme. At first I was rather disappointed that fellow clergymen would see my nonviolent efforts as those of an extremist. I began thinking about the fact that I stand in the middle of two opposing forces in the Negro community. One is a force of complacency, made up in part of Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, are so drained of self respect and a sense of “somebodiness” that they have adjusted to segregation; and in part of a few middle-class Negroes who, because of a degree of academic and economic security and because in some ways they profit by segregation, have become insensitive to the problems of the masses. The other force is one of bitterness and hatred, and it comes perilously close to advocating violence. It is expressed in the various black nationalist groups that are springing up across the nation, the largest and best known being Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement. Nourished by the Negro’s frustration over the continued existence of racial discrimination, this movement is made up of people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incorrigible “devil.”

I have tried to stand between these two forces, saying that we need emulate neither the “do nothingism” of the complacent nor the hatred and despair of the black nationalist. For there is the more excellent way of love and nonviolent protest. I am grateful to God that, through the influence of the Negro church, the way of nonviolence became an integral part of our struggle.

If this philosophy had not emerged, by now many streets of the South would, I am convinced, be flowing with blood. And I am further convinced that if our white brothers dismiss as “rabble rousers” and “outside agitators” those of us who employ nonviolent direct action, and if they refuse to support our nonviolent efforts, millions of Negroes will, out of frustration and despair, seek solace and security in black nationalist ideologies—a development that would inevitably lead to a frightening racial nightmare.

Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever. The yearning for freedom eventually manifests itself, and that is what has happened to the American Negro. Something within has reminded him of his birthright of freedom, and something without has reminded him that it can be gained. Consciously or unconsciously, he has been caught up by the Zeitgeist, and with his black brothers of Africa and his brown and yellow brothers of Asia, South America and the Caribbean, the United States Negro is moving with a sense of great urgency toward the promised land of racial justice. If one recognizes this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand why public demonstrations are taking place. The Negro has many pent up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them. So let him march; let him make prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; let him go on freedom rides -and try to understand why he must do so. If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history. So I have not said to my people: “Get rid of your discontent.” Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist.

But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” And John Bunyan: “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . .” So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime—the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.

I had hoped that the white moderate would see this need. Perhaps I was too optimistic; perhaps I expected too much. I suppose I should have realized that few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action. I am thankful, however, that some of our white brothers in the South have grasped the meaning of this social revolution and committed themselves to it. They are still all too few in quantity, but they are big in quality. Some -such as Ralph McGill, Lillian Smith, Harry Golden, James McBride Dabbs, Ann Braden and Sarah Patton Boyle—have written about our struggle in eloquent and prophetic terms. Others have marched with us down nameless streets of the South. They have languished in filthy, roach infested jails, suffering the abuse and brutality of policemen who view them as “dirty nigger-lovers.” Unlike so many of their moderate brothers and sisters, they have recognized the urgency of the moment and sensed the need for powerful “action” antidotes to combat the disease of segregation.

Let me take note of my other major disappointment. I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership. Of course, there are some notable exceptions. I am not unmindful of the fact that each of you has taken some significant stands on this issue. I commend you, Reverend Stallings, for your Christian stand on this past Sunday, in welcoming Negroes to your worship service on a nonsegregated basis. I commend the Catholic leaders of this state for integrating Spring Hill College several years ago.

But despite these notable exceptions, I must honestly reiterate that I have been disappointed with the church. I do not say this as one of those negative critics who can always find something wrong with the church. I say this as a minister of the gospel, who loves the church; who was nurtured in its bosom; who has been sustained by its spiritual blessings and who will remain true to it as long as the cord of life shall lengthen.

When I was suddenly catapulted into the leadership of the bus protest in Montgomery, Alabama, a few years ago, I felt we would be supported by the white church. I felt that the white ministers, priests and rabbis of the South would be among our strongest allies. Instead, some have been outright opponents, refusing to understand the freedom movement and misrepresenting its leaders; all too many others have been more cautious than courageous and have remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained glass windows.

In spite of my shattered dreams, I came to Birmingham with the hope that the white religious leadership of this community would see the justice of our cause and, with deep moral concern, would serve as the channel through which our just grievances could reach the power structure. I had hoped that each of you would understand. But again I have been disappointed.

I have heard numerous southern religious leaders admonish their worshipers to comply with a desegregation decision because it is the law, but I have longed to hear white ministers declare: “Follow this decree because integration is morally right and because the Negro is your brother.” In the midst of blatant injustices inflicted upon the Negro, I have watched white churchmen stand on the sideline and mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities. In the midst of a mighty struggle to rid our nation of racial and economic injustice, I have heard many ministers say: “Those are social issues, with which the gospel has no real concern.” And I have watched many churches commit themselves to a completely other worldly religion which makes a strange, un-Biblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular.

I have traveled the length and breadth of Alabama, Mississippi and all the other southern states. On sweltering summer days and crisp autumn mornings I have looked at the South’s beautiful churches with their lofty spires pointing heavenward. I have beheld the impressive outlines of her massive religious education buildings. Over and over I have found myself asking: “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God? Where were their voices when the lips of Governor Barnett dripped with words of interposition and nullification? Where were they when Governor Wallace gave a clarion call for defiance and hatred? Where were their voices of support when bruised and weary Negro men and women decided to rise from the dark dungeons of complacency to the bright hills of creative protest?”

Yes, these questions are still in my mind. In deep disappointment I have wept over the laxity of the church. But be assured that my tears have been tears of love. There can be no deep disappointment where there is not deep love. Yes, I love the church. How could I do otherwise? I am in the rather unique position of being the son, the grandson and the great grandson of preachers. Yes, I see the church as the body of Christ. But, oh! How we have blemished and scarred that body through social neglect and through fear of being nonconformists.

There was a time when the church was very powerful—in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society. Whenever the early Christians entered a town, the people in power became disturbed and immediately sought to convict the Christians for being “disturbers of the peace” and “outside agitators.”’ But the Christians pressed on, in the conviction that they were “a colony of heaven,” called to obey God rather than man. Small in number, they were big in commitment. They were too God-intoxicated to be “astronomically intimidated.” By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests.

Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent—and often even vocal—sanction of things as they are.

But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust.

Perhaps I have once again been too optimistic. Is organized religion too inextricably bound to the status quo to save our nation and the world? Perhaps I must turn my faith to the inner spiritual church, the church within the church, as the true ekklesia and the hope of the world. But again I am thankful to God that some noble souls from the ranks of organized religion have broken loose from the paralyzing chains of conformity and joined us as active partners in the struggle for freedom. They have left their secure congregations and walked the streets of Albany, Georgia, with us. They have gone down the highways of the South on tortuous rides for freedom. Yes, they have gone to jail with us. Some have been dismissed from their churches, have lost the support of their bishops and fellow ministers. But they have acted in the faith that right defeated is stronger than evil triumphant. Their witness has been the spiritual salt that has preserved the true meaning of the gospel in these troubled times. They have carved a tunnel of hope through the dark mountain of disappointment.

I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour. But even if the church does not come to the aid of justice, I have no despair about the future. I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham, even if our motives are at present misunderstood. We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with America’s destiny. Before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched the majestic words of the Declaration of Independence across the pages of history, we were here. For more than two centuries our forebears labored in this country without wages; they made cotton king; they built the homes of their masters while suffering gross injustice and shameful humiliation -and yet out of a bottomless vitality they continued to thrive and develop. If the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop us, the opposition we now face will surely fail. We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.

Before closing I feel impelled to mention one other point in your statement that has troubled me profoundly. You warmly commended the Birmingham police force for keeping “order” and “preventing violence.” I doubt that you would have so warmly commended the police force if you had seen its dogs sinking their teeth into unarmed, nonviolent Negroes. I doubt that you would so quickly commend the policemen if you were to observe their ugly and inhumane treatment of Negroes here in the city jail; if you were to watch them push and curse old Negro women and young Negro girls; if you were to see them slap and kick old Negro men and young boys; if you were to observe them, as they did on two occasions, refuse to give us food because we wanted to sing our grace together. I cannot join you in your praise of the Birmingham police department.

It is true that the police have exercised a degree of discipline in handling the demonstrators. In this sense they have conducted themselves rather “nonviolently” in public. But for what purpose? To preserve the evil system of segregation. Over the past few years I have consistently preached that nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek. I have tried to make clear that it is wrong to use immoral means to attain moral ends. But now I must affirm that it is just as wrong, or perhaps even more so, to use moral means to preserve immoral ends. Perhaps Mr. Connor and his policemen have been rather nonviolent in public, as was Chief Pritchett in Albany, Georgia, but they have used the moral means of nonviolence to maintain the immoral end of racial injustice. As T. S. Eliot has said: “The last temptation is the greatest treason: To do the right deed for the wrong reason.”

I wish you had commended the Negro sit inners and demonstrators of Birmingham for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes. They will be the James Merediths, with the noble sense of purpose that enables them to face jeering and hostile mobs, and with the agonizing loneliness that characterizes the life of the pioneer. They will be old, oppressed, battered Negro women, symbolized in a seventy two year old woman in Montgomery, Alabama, who rose up with a sense of dignity and with her people decided not to ride segregated buses, and who responded with ungrammatical profundity to one who inquired about her weariness: “My feets is tired, but my soul is at rest.” They will be the young high school and college students, the young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders, courageously and nonviolently sitting in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience’ sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judaeo Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

Never before have I written so long a letter. I’m afraid it is much too long to take your precious time. I can assure you that it would have been much shorter if I had been writing from a comfortable desk, but what else can one do when he is alone in a narrow jail cell, other than write long letters, think long thoughts and pray long prayers?

If I have said anything in this letter that overstates the truth and indicates an unreasonable impatience, I beg you to forgive me. If I have said anything that understates the truth and indicates my having a patience that allows me to settle for anything less than brotherhood, I beg God to forgive me.

I hope this letter finds you strong in the faith. I also hope that circumstances will soon make it possible for me to meet each of you, not as an integrationist or a civil-rights leader but as a fellow clergyman and a Christian brother. Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Yours for the cause of Peace and Brotherhood,

Martin Luther King, Jr.

#letter from Birmingham jail#mlk jr#martin luther king jr#civil rights#we're still fighting his fight

0 notes

Text

Meet Rev. Charlie Stallworth, DMin

Fairfield University MPA Program Faculty Member

by Tess Long, Sr. Manager, Integrated Marketing

Photo Credit: Nicole Alekson

Rev. Charlie Stallworth, DMin, a former five-term Connecticut state representative for the 126th District, Bridgeport, joined Fairfield’s fully-online Master of Public Administration faculty two years ago, and teaches public policy and administration courses to both graduate and undergraduate students.

As a state representative, he cosponsored legislation concerning veteran’s issues, school bullying, education, public health, human services, prison reform and meeting children's special needs. Dr. Stallworth is the former commissioner on the Bridgeport Board of Police Commissioners as well.

Presently, Dr. Stallworth serves as senior pastor of the East End Baptist Tabernacle Church, in Bridgeport, and is the author of the devotional series, Before You Give Up, Consider These Things. He’s also been selected, multiple times, as one of the "100 Most Influential African Americans" in the State of Connecticut.

Dr. Stallworth received his bachelor of arts degree in bible and pastoral ministry from Selma University; earned his master of divinity degree from Vanderbilt University, School of Divinity, and earned a master of sacred theology degree from Yale University, Yale Divinity School; and received his doctor of ministry degree from the United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio.

Please share a little about your background and work prior to joining Fairfield.

I was born in a small rural town in Alabama. I attended public schools and undergrad college in Alabama. My college days were filled with exploration and appreciation. Attending undergrad at Selma University as a commuting student gave me the opportunity to cross the famous “bloody Sunday” Edmund Pettus Bridge twice a day on each commute. My further studies for graduate degrees took me to Vanderbilt University, United Theological Seminary and Yale University, while continuing to hold strongly to my southern roots of the liberation.

I pursued work in Des Moines, Iowa, after graduating from Vanderbilt, serving as a senior pastor, a role in which I served in Alabama, Iowa, and presently in Conn., with 43 years of community, church, and public service experience. Currently, I am serving in my 18th year as senior pastor of East End Baptist Tabernacle Church, in Bridgeport, Conn.

My father served in community organizations during the final days of the Civil Rights Movement after retiring from the Army. He felt that his secure retirement (secured in that no one could terminate his pay) enabled him to be a voice for many others who could not speak because of racial retaliation that could and would cost you your life. Because of my father’s involvement in issues of justice and liberation through the political process and community protest, I developed an inclination toward the political process as a method to empower and uplift. Therefore, I have always seen the roles of religion, in particular the Christian faith, and social justice as a singular task of life. I believe in separation of church and state as the original founders intended and not as it has been dastardly defined. To this end, I ran for political office and served the Connecticut State Legislature for twelve years.

You recently retired from your CT State Rep position. Could you share some of the valuable lessons learned in public service?

One of the most transformative lessons I learned is not to blame and accuse others because of political ideologies. Each elected official represents the interest of her or his constituents. Though I may disagree with one’s position, I learned not to accuse, blame, or assassinate a person’s character because he or she is doing what the constituency voted them into office to do. My position became difficult to hold due to the polarized and partisan nature of modern-day politics. Yet, I continue to believe that people have a right to argue for their best interest, even when such a position appears to me not to be for the common good of all citizens.

What more can you tell us about your public policy work?

Many people approach public work from various perspectives. I approached public work from the position of giving voice to the voiceless and working collaboratively to pass legislation. This, many times, was expressed in making a phone call, demanding proper treatment, and looking out for people that are often overlooked by society. I was greatly concerned to use my office as a voice of justice, fairness, and liberation for the poor, mistreated, overlooked, and disdained. I had multiple occasions, more than I can recall, where I made a call to a car dealership that was unfairly holding someone’s deposit, to a landlord that was not taking care of a rented property and even calls to departments within our state government asking for proper treatment. In addition, I always approached passing legislation as a collaborative effort. I had no intent to be a lone ranger.

As a reverend, in what ways do you direct your congregation toward building community, so that the impact felt by the larger community will be intentional and long-lived?

The African American church started as what scholars have called “the invisible church.” That is, enslaved people gathered late at night, deep in the woods in ad-hoc gatherings to sing songs, pray prayers, preach sermons, and uplift one another. There was not a physical structure that housed this gathering, nor was it visible to the larger society that was filled with oppression. However, the invisible church birthed into the African American church and became an extension of the family. There was not a separation of good effort for freedom and good religion. One of the songs that was often sung contained the words, “Have you got good religion?” The emphasis was on “good.” The congregation using a call and response method would respond, “Certainly, certainly, certainly Lord.” The essence of that song reflected something deeper than words and went far beyond simply claiming a religious title.

Therefore, when I speak of making the community a better place so that the impact is felt by the larger community, I mean promoting the type of faith tradition that is sustained, having sustainability, and creating positive impact on the street-level. I mean our faith should be seen in the positive transformation of public education, health care, immigration, and tax reform among many other items.

What is some advice you’d offer to students who are interested in the MPA degree at Fairfield? How can it help them in the field and what distinguishes the Fairfield program from others?

I would offer three bits of advice. One, one should enter politics and public service with an open mind. America, as I have often heard, is an idea. I believe, by being an idea, we continue to define and interpret what it means to be the United States of America and that endeavor and discussion will demand an open mind. Two, one should enter public service and politics with thick skin. My mother used to say, “If the heat is too hot then get out the kitchen.” The arena of public work and politics is filled with intense heat of scrutiny, high demands, and sometimes low appreciation. Three, one should enter and approach public service and politics as an opportunity to serve. I do not believe personal gain should ever be the driving force that calls one to public service and politics.

I believe the program at Fairfield University is unique because of its diverse and highly trained faculty who offer a combination of praxis and theory. The theory and scholarship are present, but at the end of the day we continue to ask the question, “What does this look like in real life?”

In my new role at Fairfield University, I bring to the classroom a combination of theory and praxis based on my experience as a state representative for 12 years, a police commissioner, and a senior mayoral advisor.

Learn more about Fairfield’s fully-online Master of Public Administration (MPA).

0 notes

Text

Martin Luther King From Jail

April 16, 1963

My Dear Fellow Clergymen:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statements in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.

I think I should indicate why I am here In Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against "outsiders coming in." I have the honor of serving as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization operating in every southern state, with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. We have some eighty-five affiliated organizations across the South, and one of them is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Frequently we share staff, educational and financial resources with our affiliates. Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct-action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here I am here because I have organizational ties here.

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their "thus saith the Lord" far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I. compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial "outside agitator" idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

You deplore the demonstrations taking place In Brimingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city's white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.

In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self- purification; and direct action. We have gone through an these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro .leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good-faith negotiation.

Then, last September, came the opportunity to talk with leaders of Birmingham's economic community. In the course of the negotiations, certain promises were made by the merchants --- for example, to remove the stores humiliating racial signs. On the basis of these promises, the Reverend Fred Shuttles worth and the leaders of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights agreed to a moratorium on all demonstrations. As the weeks and months went by, we realized that we were the victims of a broken promise. A few signs, briefly removed, returned; the others remained.

As in so many past experiences, our hopes bad been blasted, and the shadow of deep disappointment settled upon us. We had no alternative except to prepare for direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community. Mindful of the difficulties involved, we decided to undertake a process of self-purification. We began a series of workshops on nonviolence, and we repeatedly asked ourselves : "Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?" "Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?" We decided to schedule our direct-action program for the Easter season, realizing that except for Christmas, this is the main shopping period of the year. Knowing that a strong economic with with-drawl program would be the by-product of direct action, we felt that this would be the best time to bring pressure to bear on the merchants for the needed change.

Then it occurred to us that Birmingham's mayoralty election was coming up in March, and we speedily decided to postpone action until after election day. When we discovered that the Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene "Bull" Connor, had piled up enough votes to be in the run-oat we decided again to postpone action until the day after the run-off so that the demonstrations could not be used to cloud the issues. Like many others, we waited to see Mr. Connor defeated, and to this end we endured postponement after postponement. Having aided in this community need, we felt that our direct-action program could be delayed no longer.

You may well ask: "Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn't negotiation a better path?" You are quite right in calling, for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent-resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word "tension." I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, we must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved South land been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.

One of the basic points in your statement is that the action that I and my associates have taken .in Birmingham is untimely. Some have asked: "Why didn't you give the new city administration time to act?" The only answer that I can give to this query is that the new Birmingham administration must be prodded about as much as the outgoing one, before it will act. We are sadly mistaken if we feel that the election of Albert Boutwell as mayor. will bring the millennium to Birmingham. While Mr. Boutwell is a much more gentle person than Mr. Connor, they are both segregationists, dedicated to maintenance of the status quo. I have hope that Mr. Boutwell will be reasonable enough to see the futility of massive resistance to desegregation. But he will not see this without pressure from devotees of civil rights. My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.