#AACM

Photo

Wadsworth Jarrell of AfriCOBRA took this photo for the AACM in his backyard, probably in 1968. Left to right, on the ground: Wadada Leo Smith, Sarnie Garrett, Wadsworth Jarrell Jr., Muhal Richard Abrams, Wallace McMillan, Douglas Ewart, John Stubblefield, Steve McCall, and Henry Threadgill. On the stairs: Buford Kirkwood, John Shenoy Jackson, Lester Lashley, and Martin "Sparx" Alexander. Credit: Courtesy of George Lewis

(via Why the AACM and AfriCOBRA still matter - Chicago Reader)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

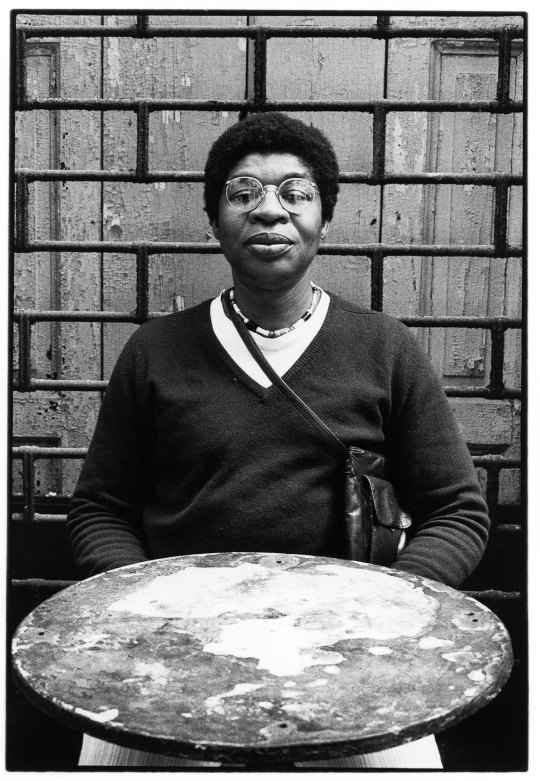

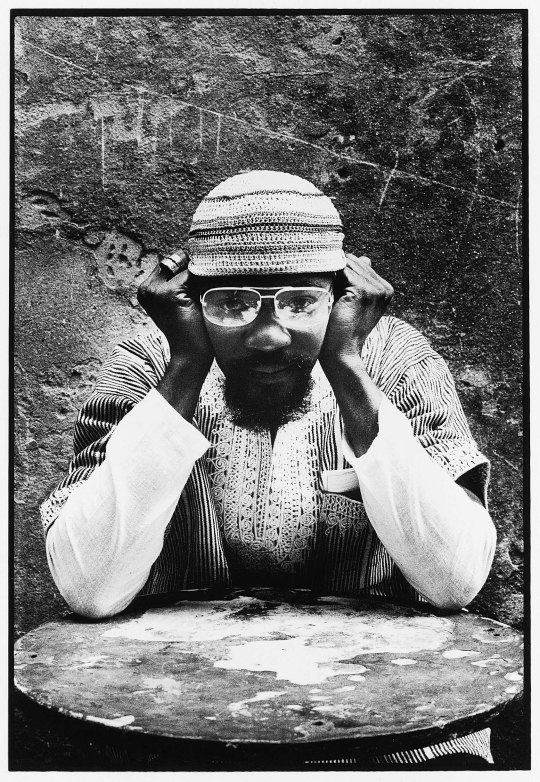

Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Milan, 1976.

Portraits of Malachi Favors, Roscoe Mitchell, Lester Bowie, Joseph Jarman and Famoudou Don Moye, Milano, 1976 — from Roberto Masotti's YOU TOURNED THE TABLES ON ME (Auditorium Edizioni, 1994).

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Threadgill — The Other One (Pi)

The Other One by Henry Threadgill

Over the last five decades, Henry Threadgill has been creating a singular body of work, as both a distinguished reed players and an inimitable ensemble leader. Early on, Threadgill cultivated his sense of ensemble arranging and playing as member of AACM in the trio Air and in groups lead by Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton and Roscoe Mitchell. But from X-75 Volume 1, his first recording under his own name released in 1979 with a group comprised of four woodwind players, three bassists, piccolo bass and vocals, he revealed a penchant for creating improvisational frameworks around distinctive voicings. Since that time, he’s honed his approach with long-standing ensembles, each building on his ear for angular, contrapuntal themes extended through open group interplay.

First up was The Henry Threadgill Sextet (a seven-piece group designated as a sextet because he saw the two drummers as a single percussion unit) featuring his alto sax along with trumpet, the low-end double bass/cello/trombone, and a percussion duo. A foray into social dance music, his Society Situation Dance Band, went unrecorded but his next ensemble, Very Very Circus, with sax, two tubas, two electric guitars, French horn, and drums added a pulsing groove while expanding on his multifaceted ear toward hocketed lines and intricate, stratified voicings. Make a Move and Zooid pared things back a bit in the size of the ensemble while still incorporating intriguing instrumental choices like paired acoustic guitars and cellos, accordion, oud and tuba. Then, with Double Up, Threadgill mixed in paired reeds, paired pianos, cello, tuba and drums, expanded even further with 14 Or 15 Kestra: Agg. With each of these ensembles, he extended his compositional approach, diving in to the timbral and dynamic opportunities afforded by an increasingly orchestral instrumental palette. All of this doesn’t even touch on the various commissions for orchestra, string quartet, and chamber ensembles he undertook.

In May 2022, Threadgill presented one of his most ambitious projects to date at Roulette Intermedium in Brooklyn, New York. The composer prepared a three-movement composition entitled “Of Valence” for a twelve-piece ensemble made up of three saxophones, violin, viola, two cellos, tuba, percussion, piano and two bassoons. The piece, inspired by Milford Graves and his integration of the human heartbeat as a source of rhythmic understanding, is a meditation on human transience based on his observations of the exodus of people from New York City during the Covid pandemic. The performance incorporated an array of multimedia components including video, projections of paintings and photographs, electronics and recordings. Each performances was split in to two sets providing varying takes on the composition, the first set titled “One” and the second titled “The Other One.” This release, Threadgill’s eleventh for the Pi Recordings label, captures the second set of one of the performances in scintillating fidelity.

The three-movement piece begins with spare, stabbing notes and rumbling open chords on piano, intently traversing the foundational angular motifs. The reeds join in setting up the entrance of the full ensemble. Threadgill maximizes the sonic breadth provided by the full range of strings and a broadened reed section. His conducting is supported by tubist Jose Davila, cellist Christopher Hoffman, pianist David Virelles and drummer Craig Weinrib, all veterans of the leader’s groups who collectively help helm the ensemble through the intricately evolving piece. Themes are introduced, fragmented, inverted, and hocketed as sections elastically play off of each other and branch off into sub-groupings as the densities of the piece ebb and flow. Threadgill’s proclivity for utilizing underlying galvanic pulse is an anchoring element, buoyed in particular by tuba, cellos and drums as the music bobs and weaves along with the countervailing, keening melodic threads.

Threadgill’s pieces demand exacting execution, and the group fully embraces the compositional form while each displaying adroit capabilities exploring the inherent opportunities for improvisation. While Threadgill sticks to conducting here, the influence of his instrumental voice is readily apparent throughout. Milford Graves’ influence is heard most overtly at the start of the second movement where violinist Sarah Caswell, violist Stephanie Griffin and cellist Mariel Roberts each play their parts while listening to a playback of their own heartbeats as recorded previously by a cardiologist. The result is that the pulse of each individual players’ lines intertwine, mutably moving in and out of synch while maintaining an unwavering, galvanizing flow. One third of the way through the 16-minute section, lissome sax lines are introduced segueing to the entrance of the full ensemble. While density builds, there is a transparency to the orchestration as lines and instruments come to the fore and then recede. Midway through, sizzling transducer-activated cymbals play off of abraded cello overtones setting the stage for a freely lyrical tenor solo which wends to a closing section with percolating pizzicato strings and pattering percussion.

The final movement kicks off with a short interlude for strings and drums, leading in to a section of abstracted melody, with alto and bassoon lines snaking around the ensemble voicings. Interludes for solos are woven through as the pacing constantly morphs. Here, sections are clear successors to the approaches that Threadgill worked through with Zooid and Double Up, inheriting the underlying coursing flow and arcing lyricism but shading and extending it with timbral orchestration, the bassoons being a particularly astute addition. In the final section, intertwined piano and tuba and the shifting shuffle of cellos and drums set the stage for an all-in re-statement of one of the central themes, leading to the finale of the piece for the full ensemble, crescendoing to dramatic intensity. Listeners have benefited from Pi Recordings’ dedication to Threadgill’s evolving and burgeoning oeuvre. The release of The Other One is a significant addition to these efforts and essential listening for those interested in Threadgill’s music.

Michael Rosenstein

#henry threadgill#the other one#pi#michael rosenstein#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#AACM#air#improvisation#composition

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quando è stata la vostra prima volta?

Tranquilli, nessuno di noi è interessato a confessioni tra il comico e lo scabroso: non si tratta di una domanda licenziosa al limite della prouderie, l’oggetto della domanda invece riguarda la vostra prima volta a contatto con la musica jazz. Come è avvenuta ? Perché una prima volta comunque c’è stata, e, a parte coloro che grazie a genitori o fratelli/sorelle più grandi e più acculturati hanno…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Silker Eberhard/Ben Lamar Gay/Mike Reed at We Jazz Festival 2022 Helsinki

#ben lamar gay#mike reed#silke eberhard#fuji gs645s#gs645s#fuji velvia 100#velvia 100#free jazz#improvised music#we jazz festival#we jazz#creative music#AACM

0 notes

Text

A new album from Kahil El’Zabar’s Ethnic Heritage Ensemble today as well - "Open Me, A Higher Consciousness of Sound and Spirit"

This is the new offering from Kahil El’Zabar and his Ethnic Heritage Ensemble, in conjunction with the legendary group’s 50th anniversary, Open Me, A Higher Consciousness of Sound and Spirit.

Open Me is a joyous honoring of portent new directions of the Ethnic Heritage Ensemble; it’s a visionary journey into deep roots and future routes, channeling traditions old and new. It mixes El’Zabar’s original compositions with timeless classics by Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner, and Eugene McDaniels. Thus, the Ethnic Heritage Ensemble continues affirming their indelible, half-century presence within the continuum of Great Black Music.

Open Me, El’Zabar’s sixth collaboration with Spiritmuse in five years, marks another entry in a run of critically acclaimed recordings that stretch back to the first EHE recording in 1981. The storied multi-percussionist, composer, fashion designer, and former Chair of the Association of Creative Musicians (AACM) is in what might be the most productive form of his career, and now in his seventies, shows no signs of slowing down. Few creative music units can boast such longevity, and fewer still are touring as energetically and recording with the verve of the Ethnic Heritage Ensemble.

The EHE was founded by El’Zabar in 1974 originally as a quintet, but was soon paired down to its classic form — a trio, featuring El’Zabar on multi-percussion and voice, plus two horns. It was an unusual format, even by the standards of the outward-bound musicians of the AACM: “Some people literally laughed at our unorthodox instrumentation and approach. We were considered even stranger than most AACM bands at the time. I knew in my heart though that that this band had legs, and that my concept was based on logic as it pertains to the history of Great Black Music, i.e. a strong rhythmic foundation, innovative harmonics and counterpoint, well-balanced interplay and cacophony amongst the players, strong individual soloist, highly developed and studied ensemble dynamics, an in-depth grasp of music history, originality, fearlessness, and deep spirituality.”

With El’Zabar at the helm, the band’s line-up has always been open to changes, and over the years the EHE has welcomed dozens of revered musicians including Light Henry Huff, Kalaparusha Maurice Macintyre, Joseph Bowie, Hamiett Bluiett, and Craig Harris. The current line-up has been consolidated over two decades — trumpeter Corey Wilkes entered the circle twenty years ago, while baritone sax player Alex Harding joined seven years ago, after having played with El’Zabar since the early 2000s in groups such as Joseph Bowie’s Defunkt.

For Open Me, El’Zabar has chosen to push the sound of the EHE in a new direction by adding string instruments — cello, played by Ishmael Ali, and violin/viola played by James Sanders. The addition of strings opens new textural resonances and timbral dimensions in the Ensemble’s sound, linking the work to the tradition of improvising violin and cello from Ray Nance to Billy Bang, Leroy Jenkins, and Abdul Wadud.

Open Me contains a mixture of originals, including some El’Zabar evergreens such as “Barundi,” “Hang Tuff,” “Ornette,” and “Great Black Music” (often attributed to the Art Ensemble of Chicago but is, in fact, an El’Zabar composition). There are also numbers drawn from the modern tradition, which El’Zabar uniquely arranges, including a contemplative interpretation of Miles Davis’ “All Blues.” As a milestone anniversary celebration and a statement of future intent, Open Me effortlessly carries El’Zabar’s healing vision of Higher Consciousness of Sound and Spirit.

All compositions by Kahil El’Zabar

except tracks ‘All Blues’ by Miles Davis, ‘He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands’ spiritual folk by Unknown, ‘Passion Dance’ by McCoy Tyner and ‘Compared to What’ by Gene McDaniels

All arrangements by Kahil El’Zabar

Tapestry and Art Direction by Nep Sidhu

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

LEROY JENKINS, VIOLONISTE DE FREE JAZZ

‘’Our music was a result of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. And we prided ourselves on taking it further, because we studied Cage, and Xenakis, and Schoenberg, and all those guys. They were the ones who broke away from the old way in classical music, so we had to study them to see how we could break away."

- Leroy Jenkins

Né le 11 mars 1932 à Chicago, en Illinois, Leroy Jenkins était issu d’une famille pauvre. Jenkins avait passé son enfance dans un appartement de trois chambres du South Side avec sa mère, sa soeur, deux tantes, et à l’occasion, un chambreur. Jenkins, qui avait été mis en contact avec la musique dès son plus jeune âge, avait raconté plus tard avoir écouté Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie et des chanteurs comme Billy Eckstine et Louis Jordan durant sa jeunesse.

Jenkins était âgé de sept ans lorsqu’une de ses tantes avait apporté à la maison un ami de coeur qui jouait du violon. Après avoir entendu le petit ami de sa tante jouer une danse hongroise plutôt difficile à exécuter, Jenkins avait demandé à sa mère de lui acheter un violon. Jenkins s’était finalement retrouvé avec une violon miniature de couleur rouge de marque Montgomery Ward d’une valeur de vingt-cinq dollars. Après avoir commencé à prendre des leçons, Jenkins s’était produit dès l’âge de dix ans à la St. Luke's Church, une des plus grandes églises baptistes de la ville, où il avait été accompagné au piano par Ruth Jones, la future Dinah Washington. Jenkins s’était éventuellement joint à la chorale et à l’orchestre de la Ebenezer Baptist Church, qui était dirigé par le Dr. O. W. Frederick, qui l’avait initié à la musique de compositeurs de couleur comme William Grant Still et Will Marion Cook. Multi-instrumentiste, Jenkins avait également appris à jouer de la clarinette, du saxophone alto, du basson et de la viole durant son enfance.

À l’adolescence, Jenkins avait étudié au légendaire DuSable High School, où il avait troqué le violon pour la clarinette et le saxophone alto, car l’école n’avait pas d’orchestre, ce qui limitait ses possibilités de jouer du violon. Au DuSable High School, Jenkins avait étudié sous la direction du célèbre ‘’capitaine’’ Walter Dyett, jouant notamment du basson et de la clarinette avec le groupe de concert de l’école.

Après avoir obtenu son diplôme, Jenkins avait décroché une bourne pour étudier à l’Université Florida A&M, où il avait décroché un baccalauréat en composition et en violon classique. Jenkins avait également fréquenté la Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University à Tallahassee, en Floride, où il avait étudié le basson. Parallèlement à ses études, Jenkins avait également obtenu un revenu d’appoint en jouant du saxophone dans les clubs locaux.

Après avoir décroché un diplôme en éducation en 1961, Jenkins s’était installé à Mobile, en Alabama, où il avait enseigné la musique (et plus particulièrement les instruments à cordes) dans un high school durant quatre ans.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Au milieu des années 1960, Jenkins était rentré à Chicago où il avait obtenu un emploi dans le système d’éducation public. Peu après, Jenkins avait assisté à un événement de l’Association for the Advancement of the Contemporary Musicians (AACM) mettant en vedette la musique du saxophoniste Roscoe Mitchell. Participaient également au concert Maurice McIntyre, Charles Clark, Malachi Favors, Alvin Fielder et Thurman Barker. Jenkins s’était rappelé plus tard avoir été à la fois confus et excité à l’idée de participer à une improvisation collective avec son violon. Jenkins avait alors commencé à participer à des répétitions dirigées par Muhal Richard Abrams. Il expliquait: "it was something different, something where I could really be violinistic... I discovered that I would be able to play more of my instrument and I wouldn't have to worry about the cliches... I found out that I could really soar, I found out how I could really play." Jenkins avait continuer de répéter et de se produire avec le groupe durant quatre ans.

Jenkins avait fait ses débuts sur disque sur l’album d’Abrams ‘’Levels and Degrees of Light’’ en 1967. À la même époque, Jenkins avait commencé à jouer en trio avec les membres de l’AACM Anthony Braxton et Leo Smith, avec qui il avait enregistré l’album ‘’3 Compositions of New Jazz’’ en 1968. Abrams avait également participé à l’enregistrement. L’année suivante, le trio de Jenkins s’était installé à Paris et avait commencé à jouer avec le batteur Steve McCall avec qui il avait formé un groupe appelé Creative Construction Company. À l’époque, McCall était déjà établi en Europe depuis quelques années.

Durant son séjour à Paris, Jenkins s’était produit avec une vaste gamme de musiciens, dont Archie Shepp, Philly Joe Jones, Alan Silva (avec qui il avait enregistré l’album ‘’Luna Surface’’) et Ornette Coleman. À un certain moment, Coleman avait organisé un concert conjoint avec la Creative Construction Company, l’Art Ensemble of Chicago de Roscoe Mitchell et son propre groupe. À la même époque, Jenkins avait également collaboré à un album de Braxton intitulé ‘’B-Xo/N-0-1-47a’’ sur étiquette BYG Actuel.

En 1970, Jenkins avait quitté Paris et était retourné à New York où il avait fondé le Revolutionary Ensemble. Le groupe, qui avait enregistré un total de sept albums, avait également fait des tournées en Amérique du Nord et en Europe.

Jenkins avait expliqué plus tard qu’il avait quitté Paris parce qu’il se sentait mal à l’aise avec le fait qu’il ne parlait pas français. À son arrivée à New York, Jenkins avait repris contact avec Coleman. Il avait même vécu durant quelques mois dans le loft du saxophoniste appelé Artists House. Jenkins précisait: "We stayed downstairs... It was cold down there, where we slept. Ornette gave us a mattress but he didn't realize how cold it was." Devenu le mentor de Jenkins, Coleman l’avait présenté à plusieurs musiciens qui fréquentaient son loft (les lofts étaient d’importants lieux d’improvisation particulièrement actifs à New York à l’époque). Outre Coleman, Jenkins avait également été très influencé par John Coltrane et Charlie Parker.

Parallèlement, Jenkins avait continué de répéter et de jouer avec la Creative Construction Company, ce qui avait donné lieu à la présentation d’un concert à la "Peace Church" de Greenwich Village le 19 mai 1970. Le concert, qui mettait également en vedette Abrams et le contrebassiste Richard Davis, avait été enregistré par Coleman avant d’être publié en deux volumes par les disques Muse. Chacun des deux albums comprenait une composition de Jenkins.

À la suite du concert, Braxton s’était joint au groupe de free jazz de Chick Corea, Circle. En 1971, Jenkins avait fondé le Revolutionary Ensemble avec le contrebassiste et tromboniste Sirone (pseudonyme de Norris Jones) et le percussionniste et pianiste Jerome Cooper. Le groupe avait poursuivi ses activités durant six ans. Parmi les albums du groupe, on remarquait le disque éponyme Revolutionary Ensemble, également connu sous le titre de ‘’Vietnam’’ (mars 1972), qui comprenait une longue jam session de 47 minutes qui visait à démontrer toute l’horreur de la guerre. Le groupe avait enchaîné en décembre de la même année avec ‘’Manhattan Cycles’’ avant de récidiver trois ans plus tard avec ‘’The Psyche’’ qui comprenait une composition de chacun des membres du groupe. Également publié en décembre 1975, l’album ‘’Ponderous Planets on The People's Republic’’ avait expérimenté avec différentes textures. Si Jenkins jouait à la fois de violon, de la viole, du piano et de la flûte sur l’album, Sirone avait alterné entre la contrebasse, les percussions et le trombone tandis que Jerome Cooper avait utilisé plusieurs techniques de percussion. L’album ‘’Ponderous Planets on The People's Republic’’ est aujourd’hui considéré comme un classique.

À la même époque, sous l’influence du Jazz Composers' Orchestra de Carla Bley et Michael Mantler, Jenkins avait assemblé une formation tout-étoile composée d’Anthony Braxton, de Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, de Dewey Redman, de Leo Smith, de Joseph Bowie (le frère du trompettiste de l’Art Ensemble of Chicago, Lester Bowie) de David Holland, de Jerome Cooper, de Charles Shaw et de Sirone dans le cadre de l’enregistrement de l’album ‘’For Players Only’’ (janvier 1975).

Après la dissolution du groupe Revolutionary Ensemble en 1977, Jenkins avait fait une tournée aux États-Unis et en Europe. En 1979, Jenkins avait formé le Mixed Quintet, un groupe composé de Jenkins au violon et à la viole, de Marty Ehrlich à la clarinette basse, de J. D. Parran à la clarinette, de James Newton à la flûte et de John Clark au cor français.

En janvier 1975, Jenkins avait publié ‘’Swift Are the Winds of Life’’ un album en duo avec l’ancien batteur et percussionniste de John Coltrane, Rashied Ali.

Au début et au milieu des années 1970, Jenkins avait également joué et enregistré avec des musiciens aussi diversifiés qu’Alice Coltrane, Cecil Taylor (1970), Anthony Braxton (1969-72), Don Cherry, Carla Bley, Albert Ayler, Grachan Moncur III, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Paul Motian, Cal Massey, Dewey Redman et Archie Shepp.

À la fin des années 1970, Jenkins avait joué et enregistré avec le pianiste et compositeur Anthony Davis et le batteur Andrew Cyrille. Au début de la décennie suivante, Jenkins avait formé le groupe de fusion Sting, une formation largement influencée par le blues qui comprenait deux violonistes (Jenkins et Terry Jenoure), deux guitaristes (Brandon Ross à la guitare électrique et James Emery à la guitare acoustique amplifiée), un bassiste électrique (Alonzo Gardner) et un batteur (Kamal Sabir). Un des meilleurs albums du groupe était ‘’Urban Blues’’ (janvier 1984), un disque qui offrait un mélange plutôt inusité de funk, d’avant-garde, de pop, de gospel, de rhythm & blues et de hip-hop.

En 1981, Jenkins avait publié l’album double ‘’Beneath Detroit’’ avec le New Chamber Jazz Quintet. L’album mettait en vedette Spencer Barefield à la guitare classique douze cordes et à la harpe africaine, Faruq Bey au saxophone ténor, Anthony Holland aux saxophones alto et soprano, Jaribu Shahid à la contrebasse et Tani Tabbal à la batterie, aux percussions et au balafon.

À la même époque, en plus de s’être classé en bonne position dans les sondages des lecteurs et des critiques de Down Beat et de Jazz Magazine, Jenkins avait décroché plusieurs bourses et commandes du New York State Council on the Arts, de la New York Foundation for the Arts, de la Fondation Rockefeller, de Meet the Composer, de Mutable Music et du National Endowment for the Arts (1973, 1974, 1978, 1983 et 1986). Durant cette période, Jenkins avait aussi reçu de commandes d’organismes prestigieux comme le Kronos Quartet, le Brooklyn Philharmonic, le New Music Consort, le Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble, du Lincoln Center Out of Doors, de l’Albany Symphony et du Cleveland Chamber Symphony Orchestra.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Les années 1980 et 1990 avaient été plutôt difficiles pour Jenkins, qui avait commencé à avoir des difficultés à se trouver des contrats pour la première fois de sa carrière. Comme Jenkins l’avait expliqué au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine Village Voice, le milieu du jazz était devenu beaucoup plus conservateur, ce qui avait laissé beaucoup moins de place pour le jazz d’avant-garde. Il précisait:

"Wynton Marsalis was in, and people started talking about going back to classic jazz. We couldn't play in clubs. As soon as we'd walk in, the jazz guys, the beboppers, would walk out. We'd come in and make a big sound, and they didn't go for it. They'd say, 'Oh, the noisemakers.' They wanted chord changes. Our music was a result of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. And we prided ourselves on taking it further, because we studied Cage, and Xenakis, and Schoenberg, and all those guys. They were the ones who broke away from the old way in classical music, so we had to study them to see how we could break away."

À la fin des années 1980, Jenkins avait quand même réussi à enregistrer et à participer à des tournées avec le quintet de Cecil Taylor, même si les choses n’étaient décidément plus ce qu’elles étaient.

Même s’il n’avait presque plus enregistré au milieu des années 1980 et au début des années 1990 et qu’il avait presque abandonné le jazz pour se consacrer à la composition de musique classique, Jenkins avait été très actif dans le Composers Forum, un groupe de pression de New York. Au cours de cette période, Jenkins s’était également produir en duo avec le saxophoniste Joseph Jarman de l’Art Ensemble of Chicago.

À la même époque, Jenkins avait continué de démontrer ses talents d’improvisateur, notamment dans le cadre de son album ‘’Solo’’ (1998), un enregistrement sans accompagnement dans lequel il avait revisité les oeuvres de John Coltrane et de Dizzy Gillespie. Il ne s’agissait pas du premier album solo de Jenkins, qui avait déjà publié en janvier 1977 un album live intitulé Solo Concert, qui avait été suivi en juillet 1978 de l’album ‘’Legend of Ai Glatson.’’ Jenkins avait également publié d’autres enregistrements en solo sur l’album ‘’Santa Fe’’ en octobre 1992.

Parmi les albums néo-classiques de Jenkins, on remarquait ‘’Lifelong Ambitions’’ (mars 1977) avec Muhal Richard Abrams, une improvisation électronique de vingt et une minutes avec Richard Teitelbaum et George Lewis aux synthétiseurs dans le cadre de l’album ‘’Space Minds/ New Worlds/ Survival America’’ (septembre 1978), le Quintet No 3 pour violon, cor français, clarinette et clarinette basse (enregistré avec Marty Ehrlich), l’album ‘’Mixed Quintet’’ (mars 1979) et la pièce ‘’Free at Last’’ publiée sur l’album ‘’Straight Ahead/ Free at Last’’ (septembre 1979) mettant en vedette le violoncelliste Abdul Wadud.

Toujours dans les années 1990, Hans Werner Henze, le directeur artistique du Munich Biennial New Music Theatre Festival, avait chargé Jenkins de composer un danse-opéra intitulé ‘’Mother of Three Sons’’ (1991), une oeuvre qui faisait une sorte de synthèse entre les danses africaines, le jazz d’avant-garde et le folklore d’origine africaine. L’oeuvre, qui racontait l’histoire d’une femme qui tentait de donner naissance à des fils parfaits en copulant avec les dieux, s’appuyait sur la collaboration du chorégraphe et réalisateur Bill T. Jones et de la livrettiste Ann T. Greene. L’oeuvre, qui avait été présentée en grande première à Aachaen en Allemagne en 1990, avait également été interprétée par le New York City Opera en 1991 et le Houston Grand Opera l’année suivante.

Jenkins avait poursuivi son exploration de la musique classique dans les années 1990 et 2000 avec des oeuvres comme ‘’Fresh Faust’’ (1994), un opéra de jazz-rap (dans lequel il revisitait la légende de Faust) qu’il avait composé pour l’Institute of Contemporary Art de Boston, et ‘’The Negro Burial Ground’’ (1996), une cantate produite par la troupe The Kitchen et qui avait été présentée par l’Université du Massachusetts à Amsherst. Basée sur un livret d’Ann T. Greene, l’oeuvre traitait de la pierre tombale d’un esclave du 18e siècle qui avait été découverte en 1991 sur une propriété de Wall Street. Parmi les autres oeuvres majeures de Jenkins, on remarquait ‘’Editorio - The Three Willies’’ (1996), un opéra multimédia qui avait été présenté au Painted Bride de Philadelphie ainsi que ‘’Coincidents’’, un opéra basé sur un livret de Mary Griffin. L’oeuvre avait été présentée à la Roulette de New York.

Même s’il enregistrait beaucoup moins, Jenkins avait fait paraître d’autres albums dans les années 1990, dont ‘’Themes and Improvisations on the Blues’’ (1992), qui mettait en vedette des cordes, des cuivres, de la contrebasse et du piano sur quatre pièces. En 1993, Jenkins avait enchaîné avec un album en concert intitulé ‘’Leroy Jenkins Live!’’ qui comprenait à la fois une section rythmique traditionnelle et des synthétiseurs.

À la même époque, Jenkins avait également participé à une réunion du Revolutionary Ensemble. En 1998, Jenkins avait enregistré avec le multi-instrumentiste Joseph Jarman de l’Art Ensemble og Chicago l’album ‘’Out of the Mist’’, un enregistrement qui combinait la musique africaine et asiatique au jazz, en passant par la musique classique européenne contemporaine. Par la suite, Jenkins avait prolongé sa collaboration avec Jarman en formant le trio Equal Interest avec la pianiste Myra Melford. Le groupe avait publié un album éponyme en 2000 qui refétait les intérêts de chacun de ses membres. Le critique du magazine Down Beat, James Hale, avait écrit au sujet de cet album: "Jarman's devotion to Buddhism dovetails with Melford's interest in music for the harmonium, while Jenkins thrives on developing thematic patterns that span musical cultures from East Asia to Appalachia. Together, the three create music that defies categorization beyond the beauty and humanity that suffuse all of it."

En 2004, Jenkins avait formé le groupe Driftwood, un quartet qui comprenait Min Xiao-Fen au pipa, Denman Maroney au piano et Rich O'Donnell aux percussions. Le groupe avait publié l’album ‘’The Art of Improvisation’’ en octobre de la même année. En 2005, Jenkins avait retrouvé le Revolutionary Ensemble avec qui il avait publié deux albums live: ‘’The Boundary of Time’’ (mai 2005) et ‘’Counterparts’’ (novembre 2005). Le groupe avait publié son dernier album studio en juin 2004. Intitulé ‘’And Now’’, l’album comprenait une composition de vingt et une minutes du batteur Jerome Cooper.

Au cours de sa carrière, Jenkins avait collaboré et fait des tournées avec de nombreux chorégraphes. Il avait également fondé un groupe d’improvisation basé sur la World Music. En 2004, Jenkins avait été lauréat d’une bourse de la Fondation Guggenheim. Il avait aussi joué comme musicien-résident dans plusieurs universités américaines, dont les universités Duke, Carnegie Mellon, Williams, Brown, Harvard et Oberlin. Également professeur, Jenkins avait enseigné la musique dans un high school de Mobile, en Alabama, de 1961 à 1965, puis dans les écoles de Chicago de 1965 à 1969.

Leroy Jenkins est mort d’un cancer du poumon à New York le 24 février 2007. Il était âgé de soixante-quatorze ans. Au moment de sa mort, Jenkins travaillait sur deux nouveaux opéras: une histoire du quartier South Side de Chicago, et ‘’Minor Triad’’, un drame musical sur les artistes de jazz Paul Robeson, Lena Horne et Cab Calloway. Jenkins vivait à Brooklyn au moment de son décès. Jenkins laissait dans le deuil son épouse Linda Harris et sa fille Chantille Kwintana. Le dernier membre survivant du groupe Revolutionary Ensemble, le batteur Jerome Cooper, est mort en 2015.

Influencé par plusieurs styles musicaux allant de la musique afro-américaine au bebop en passant par la musique classique européenne, Leroy Jenkins, qui avait été un des principaux leaders du jazz d’avant-garde durant quatre décennies, n’avait jamais cessé de se réinventer. Comme l’avait déclaré un critique du San Francisco Chronicle, "Jenkins is a master who cuts across all categories." Au cours de sa carrière, Jenkins avait publié une douzaine d’albums sous son propre nom.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Leroy Jenkins.’’ Wikipedia, 2024.

‘’Leroy Jenkins Biography.’’ Net Industries, 2024.

RATLIFF, Ben. ‘’Leroy Jenkins, 74, Violinist Who Pushed Limits of Jazz, Dies.’’ New York Times, 26 février 2007.

SCARUFFI, Pierro. ‘’Leroy Jenkins.’’ Piero Scaruffi, 2006.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from mathiasvef.com and IG mathiasvef - 28th November 2022

PART 2

2016, 21x30cm

Photographic Print & GHB/GBL

Tom Wlaschiha became famous as the man without a face in Game of Thrones. I had the chance to let his face dis and re-appear in many forms!

Two more to come!

The work was created during an Artist Residency @livingbauhauskunststiftung in 2016, Thank Maik for an amazing summer overlooking Berlin from Spree, to Alexanderplatz and Berghain.

Tom W, 2016

21x30cm, Photographic Print & GHB/GBL

Please check out www.mathiasvef.com/portfolio/aacm

Or come to @danpearlman on December 10th from 2-6 pm!

#tomwlaschiha #got #gameofthrones #JaqenHghar #FacelessMen #Braavos #strangerThings

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tadpole🔹they/them🔹19

Hello ^_^ The name's Tad. Welcome to my art blog! 🍔 Happy dining 🍽️✨

abt 🍟 main blog: @men-in-gitis 💙

tags: #ggatc (main story), #aacm (side story), #oc tag [name], #[medium/year]

comms: open on the DL (msg/email me!) ✉️

DNI terfs, "proshippers", etc. + if you make me uncomfortable I'll block you 🚫

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art Ensemble of Chicago

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

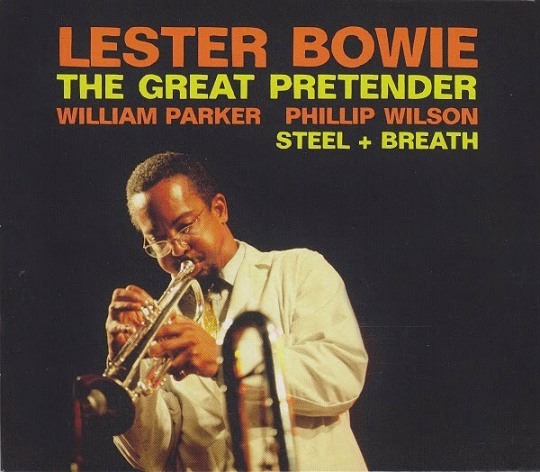

Lester Bowie (October 11, 1941 – November 8, 1999) was a jazz trumpet player and composer. He was a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians and co-founded the Art Ensemble of Chicago. At the age of five, he started studying the trumpet with his father, a professional musician. He played with blues musicians such as Little Milton and Albert King, and rhythm and blues stars such as Solomon Burke, Joe Tex, and Rufus Thomas. He became Fontella Bass's musical director and husband. He was a co-founder of the Black Artists Group in St Louis. He moved to Chicago, where he worked as a studio musician, met Muhal Richard Abrams and Roscoe Mitchell, and became a member of the AACM. In 1968, he founded the Art Ensemble of Chicago with Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, and Malachi Favors. He remained a member of this group for the rest of his life and was also a member of Jack DeJohnette's New Directions quartet. He lived and worked in Jamaica and Africa, and played and recorded with Fela Kuti. onstage appearance, in a white lab coat, with his goatee waxed into two points, was an important part of the Art Ensemble's stage show. He formed Lester Bowie's Brass Fantasy, a brass nonet in which he demonstrated jazz's links to other forms of popular music, a decidedly more populist approach than that of the Art Ensemble. With this group, he recorded songs previously associated with Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, and Marilyn Manson, along with other material. His New York Organ Ensemble featured James Carter and Amina Claudine Myers. He was part of the jazz supergroup The Leaders. Featuring tenor saxophonist Chico Freeman, alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe, drummer Famoudou Don Moye, pianist Kirk Lightsey, and bassist Cecil McBee. At this time, he was playing the opening theme music for The Cosby Show. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CjkkCxjLeNb/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

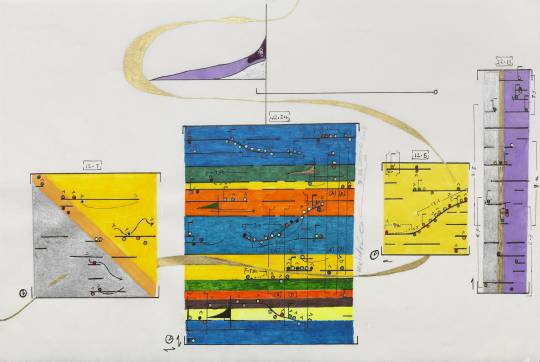

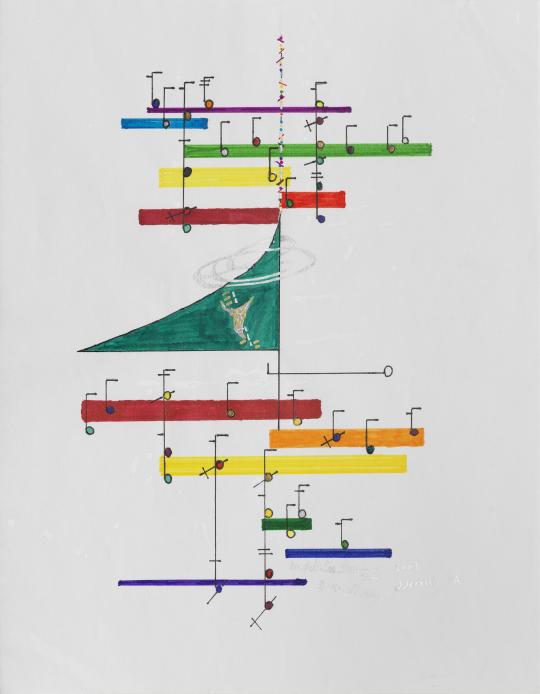

Graphic notation by Wadada Leo Smith

Trumpeter, composer, educator, and visual artist Wadada Leo Smith is a pioneer in the fields of contemporary jazz and creative music. During the 1960s and early ’70s, Smith was based in Chicago, where he was a key member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM).

Smith was one the most active and articulate proponents of this exchange, legitimizing a formal ideology around improvised music and the illustrated score that he continues to build on to this day. Ankhrasmation—a neologism formed of “Ankh,” the Egyptian symbol for life, “Ras,” the Ethiopian word for leader, and “Ma”, a universal term for mother—is the systemic musical language that Smith has developed over nearly 50 years. The scores eschew (and at times incorporate) traditional notation in favor of symbolic compositions of color, line, and shape. These provide specific instruction for the seasoned improvisor while allowing musicians to bring their own special expertise and individual strengths to each performance.

https://renaissancesociety.org/exhibitions/4/wadada-leo-smith-ankhrasmation-the-language-scores-1967-2015/

0 notes

Text

Rempis / Abrams / Ra + Baker — Scylla (Aerophonic)

Scylla by Rempis/Abrams/Ra + Baker

The Dusted review of Dave Rempis, Joshua Abrams, and Avreeayl Ra’s first album, Aphelion, closes on an anticipatory note: “This is an enormously satisfying record, but it also implies potentialities that make this a band worth watching in years to come.” I can’t claim any great gift of prescience, since all of the participants were already known both for their individual gifts. Alto, tenor and baritone saxophonist Rempis, the trio’s instigator, has a particular knack for keeping his ensembles going and growing. But I will gladly claim that I was right.

Rempis first convened the group at a time when certain of his long-standing local partnerships had come to an end or were getting harder to sustain, since they had members who were either leaving Chicago or getting busy leading their own projects. This group wasn’t an obvious solution to such problems, since Abrams and Ra were already in high demand. But it was an open door into an AACM-informed method of music-making that Rempis hadn’t spent much time pursuing. His early responses to his bandmates’ non-North American percussion and stringed instruments was to play melodies that seemed to look eastward without explicitly enacting any particular ethnic approach. But since then, the ensemble has grown into its own rhythm and identity. They play a couple times a year at Elastic Arts, the venue that hosts the long-standing weekly improvisational music concert that Rempis has booked for a couple decades. Abrams tends to leave his harp, guembri and clarinet at home now, sticking mostly to double bass, and the group’s pan-cultural intimations have been absorbed into a distinct group dynamic that contains stormy episodes within a predominantly patient approach to long-form improvisation. While Ra and Rempis are both quite at home playing at high volume, they often turn things down a notch in each other’s presence. And a fourth member, piano and synthesizer player Jim Baker, has become an integral member of the group.

Scylla, the group’s fourth recording, was recorded in July, 2021. It documents their first post-lockdown concert, and also the first performance that Elastic Arts had opened to the public since March 2020. The album actually starts with a finale, a brief dedication that Ra had originally intoned as he gently plucked his mbira at the concert’s end: “This is for the survivors.” The rest comprises two pieces, one nearly 35 minutes long, the other a bit over 27, each collectively improvised in a fashion that applies the quartet’s vocabulary to the gravity of the moment. Baker plays piano on “Between A Rock,” and his swirling chords mesh with Ra’s cymbals and Abrams arco passages to suggest a particularly oceanic surge of sound. Rempis rides their swells, switching between horns to signal a transition from pensive solemnity to purgative emotion, and finally engagement with an uncommonly bop-like closing passage. “Viscosity,” with Baker on burbling synthesizer, feels simultaneously diffuse and purposeful, as each musician carefully steers a path forward. It’s easy to project all sorts of metaphorical meaning to the music, but you’ll get just as much benefit from simply sinking into its meandering flow and savoring the common understanding that permits the collective generation of something simultaneously loose and cohesive, lyrical yet quite unforced.

Bill Meyer

#dave rempis#joshua abrams#Avreeayl Ra#Jim Baker#scylla#aerophonic#bill meyer#albumreview#dusted magazine#free jazz#aacm#Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians

1 note

·

View note

Text

360 Community HOA Management Company

360 Community Management has a dedicated team of professionals that will provide an unparalleled level of customer service for your residential condominium or homeowner association needs.

360 Community Management, your Phoenix HOA management company, is a proud member of CAI (Community Association Institute), AACM (Arizona Association of Community Managers), and the Arizona chapter of the Better Business Bureau. With the constantly changing legislation regarding homeowner associations, the team at 360 Community Management continues to educate themselves through AACM and CAI affiliates and carefully scrutinize new legislation in order to inform the homeowners associations of these changes.

COMPANY DETAILS:

Website: https://www.360propertymgt.com

Phone: (602) 863-3600

Google+: https://www.google.com/maps?cid=7766505605610275259

Address: 7272 E Indian School Rd #540, Scottsdale, AZ 85251

1 note

·

View note

Text

360 Community HOA Management Company

Established in 2001 we are not the largest condominium and homeowners association management company in the valley, however, our intention has always been to manage a limited, select group of homeowner associations in a professional manner with the highest level of integrity, and personal attention in order to ensure a high level of quality for your homeowner association. With the constantly changing legislation regarding homeowner associations, the team at 360 Community Management continues to educate themselves through AACM and CAI affiliates and carefully scrutinize new legislation in order to inform the homeowners associations of these changes.

Company Details:

Google: https://www.google.com/maps?cid=12001368876735628065

Website: https://www.360propertymgt.com

Phone: (602) 863-3600

Address: 4130 E Van Buren St #360, Phoenix, AZ 85008

1 note

·

View note