#1823 was the year he joined his father in the navy

Text

The Fantastic Union Navy Four as Midshipmen

.

Obviously this is all just my imagining 👀🙈 — they were never midshipmen concurrently (in fact, by the time Dolph joined in 1826, Glasgow was already a Lieutenant (and married for 2 years already(!))). How they looked is also my imagining, though I tried to base it on their younger selves' looks.

The number on top of them (in the fifth picture) is the age when they were first commissioned midshipman¹, while the number below is the year of their commission¹. Farragut was commissioned in 1810 (aged 9), Lee was commissioned in 1825 (aged 13), Dahlgren was commissioned in 1826 (aged 17).

(1— except for Deedee — the year 1823 was more the year when he first sailed with his father in the Navy (he was probably rated boy seaman at this point). Porter was properly commissioned midshipman in the US Navy only in 1829, aged 16)

#interesting when you put them all together like this#dolph was the second oldest but joined the last among the four#as for deedee's year it's kinda fuzzy actually...#1823 was the year he joined his father in the navy#but he was only properly comissioned midshipman in 1829#(it was a long story honestly lmao)#drawing#original art#manga#pen and ink#traditional art#fountain pen#fan art#david farragut#david glasgow farragut#john a dahlgren#john dahlgren#samuel phillips lee#david dixon porter#midshipman monday#american history#american civil war#maritime history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Admiral Sir Sidney Smith

Well, Sidney Smith was one of the most colourful personalities of his time. He was arrogant, wilful, pompous, energetic, extravagant, capable, brave, theatrical and boastful. A flamboyant genius who could not stop talking about himself, and who claimed that he was perhaps the best English-Frenchman that ever lived , he was nonetheless always happy to dispense praise on others, generally after they had been inspired to great deeds by his over-brimming self-confidence, diligence and determination. He had a reputation for being kind-tempered, kind-hearted, and generally agreeable, but in warfare took more risks with the lives of his men than his contemporary, Lord Cochrane.

Admiral Sir Sidney Smith,by Louis-Marie Autissier 1823

If you listened to original voices from the time. Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Troubridge declared that Smith made him sick, while Admiral Lord Exmouth called him gay and thoughtless. And even Nelson is reported to have said he was the gayest man in the Navy who behaved like one. Well he was of a slight build, penetrating dark eyes, a high-arched nose, striking and sharp looks and dark curly hair. Smith, like his father who had been a rake, was a lady s man, with very good manners and a razor-sharp mind, proficient in several languages and artistic talents. All in all, Sir Sidney Smith, whose real name was William Sidney Smith, was an interesting man.

He was born on 21 June 1764 in Park Lane, London, joined the Royal Navy in 1777 and soon distinguished himself in combat. He first distinguished himself in the American Revolutionary War, as a result of which he was promoted to lieutenant in 1780. This was despite the fact that he was not yet 19 years old. He served on HMS Alcide 74- guns, under Captain Charles Thompson, on which he was present at the Battle of Chesapeake on 5 September 1781, at St Kitts on 25 and 26 January 1782 and at the Saintes on 12 April. These successes led to his promotion to Master and Commander as early as 1782, and only one year later on 7 May to Post Captain. At that time he was only 18 years old. During this time he had built up a reputation as one of the most successful prize bringers, having managed to capture several prizes with his Sloop Fury, 16-guns and earning a sum of around 30,000 pounds. (By today's standards, that would be about 5 million pounds.) After that, his luck ran out, because he was discharged from the service and was then on half- pay, because of peace.

Now unemployed, he moved to Bath to study French, but when he heard in 1787 that there might be a war with Morocco, he secretly went there to study the coast and the language. In short, he tried his hand at being a spy. But when he returned home to present his findings to the admiralty, he was not able to do so. Because there was no more talk of a possible war and he was once again empty-handed. After his efforts to take up an ambassadorial role in China had been unsuccessful, Smith took six months' leave in Sweden in 1789. The following January, he reappeared in London with an embassy from King Gustav III of Sweden and a request to be allowed to serve in the monarch's fleet. The government did not approve of this unofficial emissary and so he returned to Sweden claiming to be in possession of dispatches for the King to serve as a volunteer in the war with the Russians. Assigned as commander of the light squadron, his fleet of a hundred galleys and gunboats dislodged the Russians from the islands protecting Vyborg Bay, where they had blockaded the Swedish fleet in June, thus leading to their relief.

Battle of Vyborg Bay June 25, 1790 , by Ivan Aivazovsky 1846

Although he did not act officially, he was knighted by the King of Sweden in 1790 for his actions, which caused great amusement in England. Yet he returned home briefly, only to try his luck at the Prussian court for the next two years. Initially tolerated and advised against the Russians at court, his political views became more and more disapproved of and in 1892 he tried to enter Turkish service. When he heard in 1793 that there was going to be a war between England and France, he tried to come back home and although he was still under half-pay, he was given a new commission. Although he did not act officially, he was knighted by the King of Sweden in 1790 for his actions, which caused great amusement in England. Yet he returned home briefly, only to try his luck at the Prussian court for the next two years. Initially tolerated and advised against the Russians at court, his political views became more and more disapproved of and in 1892 he tried to enter Turkish service.

When he heard in 1793 that there would be a war between England and France, he tried to return home. He obtained a felucca and, dressed in Arab robes and turban, sailed to Toulon to offer his services to Admiral Lord Hood, who was trying to support the French royalist forces. It was on this occasion that Sydney Smith and Horatio Nelson first met. The young revolutionary Colonel of Artillery Napoleon Bonaparte was rapidly decimating the royalist forces. Admiral Hood asked Sidney Smith, who was serving as a volunteer, to destroy as many royalist ships in the harbour as possible to protect them from the revolutionaries. He succeeded in destroying about half the fleet, despite the lack of supporting forces. In July 1795, again officially in the service of the Royal Navy, his squadron captured and fortified a small island off the coast of Normandy, which served as a forward base for the British blockade of Le Havre for the next seven years. On 19 April 1796, he used his ship's boats to take out a French ship anchored in Le Havre.

Sir Sidney Smith Transferred from thence to the Tower of the Temple on the 3rd July 1796

As he sailed out of the harbour, the wind suddenly died and Captain Sidney Smith and his crew were captured. He himself was taken to Temple Prison in Paris. Despite all offers from the British government to buy him out or exchange him for a French captain, the French refused. Sidney's reputation had preceded him and he was known to be a keen spy. He stayed in prison for two years until he managed to free himself with forged release papers. On his return to London, Smith was received by Earl Spencer, First Lord of the Admiralty, for a private audience with the King, and as a sign of goodwill, His Majesty sent the esteemed Captain Bergeret back to France in exchange. He was sent to the Mediterranean in 1799 and charged with reinforcing the defences in the Levant for protection against Napoleon, who was moving his army east and north from Egypt. When Napoleon laid siege to Acre in the same year, Sidney Smith used his guns to support the defenders and his fleet to supply them, and did so as an independent commander . This arrogance with which he performed earned him a sharp rebuke from both Admiral the Earl of St Vincent and Rear Admiral Lord Nelson, who as the next flag officer was particularly outraged that Smith had taken the right to hoist a broad pennant as commodore when he should have been under his command. The situation was only resolved when the broad pennant was brought down and Smith submitted to Nelson .

Napoleon eventually abandoned the siege and said of Sidney Smith, "This man made me miss my destiny." Smith's success in halting the French advance was rewarded a pension of 1,000 guineas, along with many other awards, including a coveted Chelengk and a sable coat from the Turkish Sultan. For their part, the French were so annoyed with him that Buonaparte apparently tried to have him assassinated. From 1799- 1806 he had small operations in the Mediterranean and in 1800 even tried to conclude an agreement with French General Jean-Baptiste Kléber to evacuate French troops on British ships. However, Admiral Lord Keith did not agree, so there were disputes in Keiro until the agreement was reached in 1802. Sidney had been back in London since 1801. Where he was elected to the British House of Commons as MP for Rochester in 1802. He held this mandate until 1806.

Commodore Smith at Acre

Unlike most senior naval officers in home waters, Smith did not attend Vice Admiral Lord Nelson's funeral in London on 9 January 1806. Instead, after a brief stay in Bath, he arrived in Plymouth on 14 January to sail with a small squadron to the Mediterranean to join Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood. Were he land forces commanded in southern Italy trying to defeat a superior French force. Despite a great victory, he was replaced by a British Army officer, largely because he once again could not control his famous arrogance. On the one hand, he had exceeded his command, even though he had been rear- admiral since 1805, and on the other, he had antagonised the French generals by sending them newspaper cuttings about his great successes.

In October 1807, he cruised off the mouth of the Tagus and in November escorted Prince Regent John of Portugal, who had been expelled by the French, and the royal family to Rio de Janeiro in the Portuguese colony of Brazil. There, the Prince Regent decorated him as a Grand Knight of the Order of the Tower and the Sword. In February 1808, he was appointed commander-in-chief of the British fleet off South America and, contrary to his orders, subsequently planned an attack on the neighbouring Spanish colonies together with the Portuguese. Before these plans could be implemented, he was ordered back home in July 1809.

Sir William Sidney Smith, by William Say 1802

On 31 July 1810, he was promoted to Vice Admiral of the Blue. Between 1812 and 1814 he operated in the Mediterranean as Admiral Pellew's second-in-command, during which time he was decorated in Sicily by King Ferdinand as a Grand Knight of the Cross of the Order of St Ferdinand and of Merit. After Napoléon Bonaparte was defeated in 1814 and exiled on Elba, he returned to England. On 2 January 1815, in recognition of his services, he was struck Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath by King George III, and thus at last received a British knighthood.

On 15 June 1815, he attended the Duchess of Richmond's ball in Brussels. Three days later, hearing gunfire, he rode out and met the Duke of Wellington, who had just defeated the returning Napoléon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo. Smith then accepted the surrenders of the French garrisons at Arras and Amiens and ensured the Allies entry into Paris without a fight, as well as King Louis XVIII's safe return there.

After the war, he lived mainly in Paris with his wife. He took part in the Congress of Vienna and campaigned for the abolition of slavery and debt bondage, and in particular for the raising of funds to free Christian slaves from the Barbary pirates. He was promoted to the rank of Admiral of the Red on 19 July 1821, and Lieutenant-General of the Royal Marines on 28 June 1830, but did not hold a naval command of his own after 1814. His wife died in 1826 and on 20 July 1838 he was raised by Queen Victoria to the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. Smith died on 26 May 1840 at his residence of No. 9 Rue d Auguesseau in Paris, he was 75 years old.

#naval history#persons of the navy#admiral sidney smith#it is a very long post#i had to put it under the read further line#age of sail

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

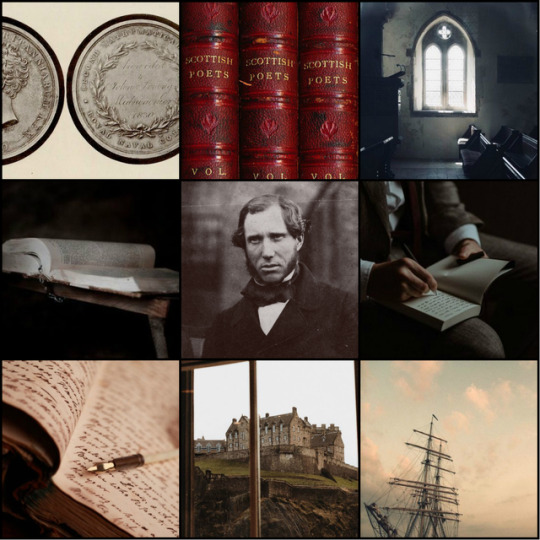

J O H N I R V I N G

(February 8th, 1815 - ??)

“So let us consider that all sorrows are meant by God to give us a distaste to this life, and a greater desire to be removed to that world where there will be no more tears or sorrows, no more partings of dear brothers and friends, but where all will be eternal, fixed, and everlasting.”

John Irving was born on February 18th, 1815, at his family home at No. 106 Princes Street in the New Town area of Edinburgh. His father, also named John, was a Writer to the Signet and a close childhood friend of famous Scottish author, Sir Walter Scott. His mother, Agnes Clerk Hay, was the eldest daughter of Colonel Lewis Hay and could claim ancestry from two well-established Scottish clans. Born to a wealthy and respected family, John—a middle child of six surviving siblings—had a life of great opportunity, but also many personal sorrows and tragedies.

Agnes Irving died at Port Seton in the summer of 1823, when John was eight years old. Growing up in her absence, later biographer Benjamin Bell recalled her as a “very excellent, godly woman” and considered her impact on her son as “doubtless”.

After his mother’s death, John became involved in his studies at the New Academy of Edinburgh, a school established by founders such as Sir Walter Scott with a focus on Classical learning, languages, natural sciences, writing, and arithmetic. The latter three categories were topics at which John would come to excel. Fellow students would recall the young Irving as, “a nice fellow, fond of play, with a good deal of quiet humour, courageous, but very slow to quarrel or take offense”. He concluded his studies before the seven-year term, and instead enrolled at the Royal Naval College in London, thereby beginning his career in the Royal Navy.

Despite a setback of a case of scarlet fever, John excelled at his studies to the extent of winning a silver medal in a mathematics competition during the Midsummer term of 1830. He would keep this medal with him as a personal token for the rest of his life. He went on to join the HMS Cordelia and HMS Fly as part of his Naval education, but it was on the HMS Belvidera where he would come into his own and form several lasting relationships.

On the Belvidera, he met fellow midshipmen William Elphinstone Malcolm (affectionately nicknamed “Elphie” by Irving) and George Kingston. Avid in their Christian faith, the three boys became particularly close. Despite a marked attitude on Irving’s part that was later recalled as a “hot temper and a rather domineering manner”, John kept these friends close for most of his life, and would keep close correspondence long after their group disbanded. He attempted to replicate this sort of group upon joining the HMS Edinburgh in 1833. However, this same faith earned his new group the disparaging nickname of the “Holy Ghost boys”, which Irving commented to William Malcolm in a letter as “horrid to relate”. Despite his difficulty socializing, Irving did document some of his adventures on the Edinburgh, such as climbing Mount Etna in Sicily (the weather conditions of which would scar his upper lip with frostbite).

However, another noted change in personality began to emerge, particularly in conjunction with the loss of his sister-in-law, Isabella, in childbirth. The tone of Irving’s letters began to show a streak of melancholy and a disillusionment with the Royal Navy. He would remark to Malcolm of his loss of interest in things of enjoyment, a detachment from his faith which alarmed him, and a disdain for Navy life. In one particularly scathing letter, he exclaimed, “I am so sick of this ship and everything belonging to it,” before reminiscing about better times on the Belvidera. Another letter saw him referring to himself as “miserable” and “wretched”, and claimed that the only thing he had hope in was the Gospel.

His fortunes, in his opinion, were about to change. In 1837, Irving resigned from the Navy in order to pursue sheep-farming in Australia, accompanied by his youngest brother, David. They were given several thousand pounds by their father and the opportunity to purchase land in New South Wales. At first optimistic about this venture, John soon began to realize that his experiences were not to go as expected. Falling wool prices, severe weather, crime, and illness plagued him, to the point that he was afflicted with a near-fatal case of dysentery that left him bedridden for five weeks. Then, in 1841, John received word that his oldest brother, George, had suddenly died of meningitis. Undoubtedly, this was another weight on an already heavy heart.

By 1843, the faltering economy had drained John of nearly all of his finances, nearly leaving him in debt. Upon recommendation from his father, John left his remaining herds and house to David and rejoined the Royal Navy, boarding onto the HMS Favourite in Sydney and returning home to Scotland.

John arrived home in the midst of an event known as The Disruption, a dramatic schism in the Church of Scotland. Baffled by what he called a “mystery”, especially with his older brother Lewis’ involvement, John characteristically commented to Malcolm that “the Gospel seems in no way concerned in the dispute”. Shortly after, he signed onto the HMS Volage and was immediately promoted to Lieutenant.

His time on the Volage was spent in a patrol of the Irish coast in the midst of a revolt advocating for Irish home rule. Irving made several observations of Irish life and politics while also displaying a change in tone towards his Navy career. By 1843, he was now in belief that he could begin on the path towards a Commandership or a Captaincy, and began looking for opportunities to advance. Near the end of the patrol, he had begun to hear rumors about an Arctic exploration attempt. Quickly gathering recommendations from past captains, he applied for the then-unnamed expedition. He spent a short time on the HMS Excellent in the waiting interim.

Upon being accepted onto the HMS Terror, Irving kept a close correspondence with his sister-in-law, Kate Irving. He included sketches of the modified locomotive engine on Terror as well as observations of personnel and ship life. Again, a tone shift became apparent as he seemed to be excited and optimistic about the Expedition and its members. In particular, he appeared to be most pleased with Captain Francis Crozier, remarking, “I like my skipper very well”. It was evident that he was pleased enough with his situation to make lighthearted jokes at the expense of Sir John Franklin, commenting to Kate that their victualing was so good on Terror that, “you need not think we have been eating our shoes”, in reference to Franklin’s famous nickname of ‘the man who ate his own boots’. Irving concluded his correspondence with a farewell letter, believing it would be some time before he would be able to write to Kate again. He expressed his belief that the Passage would be achieved, sent another sketch of Erebus and Terror anchored in a bay in Greenland, and a small sample of Tripe de Roche lichen. This was the last letter received from him.

Irving was mentioned once on the Victory Point Note later found by searchers, in the second note written on April 25th, 1848, with, “This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831.”

It wasn’t until the summer of 1879 that any further clues were found to John Irving’s fate. An expeditionary group led by Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka and a group of Inuit discovered an above-ground grave that had been picked apart by animals, but held a relatively intact skeleton. Schwatka and Austrian adventurer Heinrich Klutschak uncovered several pieces of canvas that served as the skeleton’s shroud, as well as pieces of blue fabric denoting a Naval officer’s coat, a section of a folded silk handkerchief, a spyglass, and—most notably—a silver medal laying on a flat rock outside of the grave. Further inspection revealed the medal’s owner—John Irving.

Schwatka decided to repatriate the remains back to Edinburgh. At the time, the remains were the only ones to be returned, owing to Schwatka’s belief that the skeleton had been properly identified. Word was sent to John’s older brother, Alexander, as well as his sister, Mary Scott-Moncrieff. Irving’s remaining family arrived in Edinburgh and held a funeral on January 7th, 1881. The funeral and public procession to Dean Cemetery was well-attended, with Irving’s coffin draped with a Union Jack and topped with a Lieutenant’s hat and saber. A gun salute was fired as pallbearers, all sailors, took him to his final resting place. A grave marker bore an impression of the silver mathematics medal that identified him, as well as an etching of his imagined funeral, an epitaph recalling his fate, and a set of stones recalling his grave on King William Island. The final remark came from the Book of Romans, Chapter 8, Verse 35: “ Who shall separate us from the love of Christ shall tribulation or distress - or famine".

In modern times, the identity of the skeleton buried in Edinburgh would be called into question, and indeed remains a mystery. However, there is no doubt that some part of John Irving was buried on that day in 1881, whether it was his body or his memory. To his family, at least, he found some semblance of peace and was given the rare opportunity to come home.

#franklin expedition#amc the terror#terror blogging#john irving#irving sunday#I'VE BEEN WAITING TO POST THIS ALL WEEK#NOW I'M GONNA GO PASS OUT

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Torrington: Made in Manchester

(Intro post here)

(FYI, I already wrote about a lot of the info in this post previously over here, but I want all my Torrington research grouped together in this series, so apologies for repeating myself. Anyway...)

When researching someone from history it’s a good idea to start at the beginning. When and where was John Torrington born? Who were his parents? What sort of family did he have?

But in order to find all that out, we need to work backwards. The John Torrington who signed up for the Franklin Expedition gave some important information about his life in the Muster and Allotments books. Also, and this might seem a bit morbid (of course, I’m studying a frozen corpse as a hobby, so what isn’t morbid about all this), we need to take into consideration the information on his tombstone. In tracking down his birth records, we have to match those records to what we know about him from his time with the expedition.

So what do we know about him? What things should we be looking for when tracking down his birth info?

There are three main pieces of information that we need to match with the Franklin Torrington to be sure that we’ve found the right guy:

He was born in Manchester

He was nineteen when he signed up in May of 1845 and twenty when he died on January 1, 1846, so he was most likely born during the latter half of 1825

His mother was named Mary.

It’s important to have as many pieces of additional information besides a name to match up the right person when combing through archives. There’s almost never just one person of a certain name born around the same time. Some names in particular are very common, and it can be hard to narrow down who’s who. For instance, John is an incredibly common name. In fact, it was the most common name on the Franklin Expedition, with 23 out of the original 134 crewmembers being named John. That is 17% of the crew, or more than one-sixth. If I were looking for someone named John Smith, I would probably have given up once the first page of results on Ancestry.com showed me millions of hits for that same name.

Luckily, Torrington is not that common of a last name. Searching on Ancestry gives me baptism registries for two likely candidates:

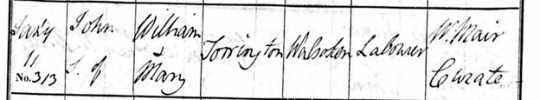

I’ll call this one JT1:

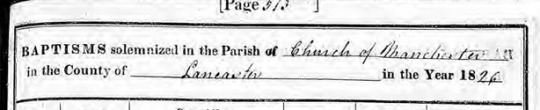

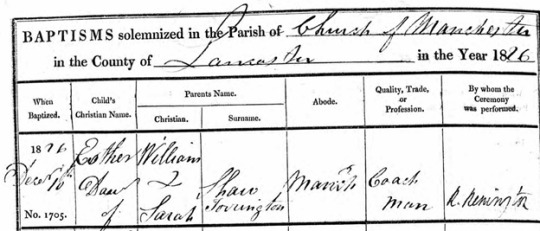

And this is JT2:

Looking at these two fine fellows we can see each one has some points in their favor, but each one also has some against. Let’s start with JT1.

JT1 was baptized in Norfolk on January 11, 1824. He lived in Walsoken, which is in the county of Norfolk. His parents were William (a laborer) and Mary. Now right off the bat we can see that JT1 gets a point in his favor by having a mother named Mary, but also two points against—he was not born in Manchester and he was baptized in early 1824, which means he most likely was born late 1823. That would make him about two years too old to be the Torrington on the Franklin Expedition.

Now, is it possible that the information in the Muster book is wrong? Yeah, sure, of course it’s possible. People didn’t have photo IDs and birth certificates they had to bring in to sign up for things back then. It’s possible that when they asked where Torrington was born, he said Manchester because he was living there at the time he joined up (I don’t know if he was living there or not, I’m just spitballing here). He could have gotten confused, or perhaps he just blatantly lied. The same is true of his age. He could have given the wrong age by accident, or on purpose. I’ve seen the wrong ages in records while hunting down Torrington’s relatives, and there are even known examples of the ages being wrong on records for the Franklin Expedition.

According to Ralph Lloyd-Jones, Thomas Evans, one of the ship’s Boys on Terror, was technically 17 when he signed up, but he was put down as 18 to meet the minimum qualifications for polar service. And then there’s William Braine, one of Torrington’s grave-mates on Beechey Island. He was born March 1814, which would have made him 32 when he passed away in April of 1846. His tombstone accurately records his age as such, but the plaque on his coffin says he was 33. It’s weird that the tombstone says one thing and the coffin plaque another, but clearly mixing up ages and dates can happen, so maybe JT1 put down the wrong age and place of birth and he’s the right guy. But that’s depending on a lot of ifs and buts to make it work.

Let’s take a look at the other option.

JT2 was baptized December 10, 1826 in Manchester. His full name was John Shaw Torrington and his parents were William (a coachman) and Sarah. Now, this Torrington was born in the right place, but he’s got the wrong mom and, yet again, the wrong birth year. Interestingly, his father has the same name as JT1’s, but he has a different profession. Is this the same William?

Looking further into it, William Torrington married Sarah Shaw on May 18, 1823. He was listed as a coachman on his marriage certificate, too, so this has to be a completely different William Torrington from JT1’s father (also, an intriguing fact to note, William signed his name with an X while Sarah was able to give her full signature). But how could JT2 possibly be the right Torrington when his mother isn’t named Mary? Wouldn’t that make JT1 a better fit?

Not exactly.

While yes, JT2’s birth mother was Sarah, she sadly passed away in 1833. Three years later, in 1836, William remarried (weirdly enough, he was able to sign his name now). Who was his second wife? A widow by the name of Mary Hoyle.

So JT2 did have a mother named Mary by the time he entered the Navy to join the expedition, and he was born in Manchester, which gives him two points in his favor. I've noticed when researching Torrington that it seems John Shaw has been unofficially recognized as the Torrington who sailed with Franklin. Even on Torrington's Wikipedia page, his name is listed as John Shaw, even though the reference listed for his name doesn't actually say that. After comparing his record to the only other known John Torrington who would be around the right age, I agree that he's the one.

But what about his birthdate? Wouldn’t being born in 1826 make him too young to be our guy?

Well, all the arguments I mentioned before about how dates and ages could be wrong still stand in this situation, so it’s possible he just aged himself up a bit, on purpose or not. But we also need to keep in mind that this is his baptism registry and not his birth certificate, so it could be days, weeks, or even months later than his actual birth. In fact, I’ve heard that some families would wait years before baptizing a child. Sometimes, they would wait until they had another kid or two in tow before hauling them all in to get a holy dunking. Did something like that happen here?

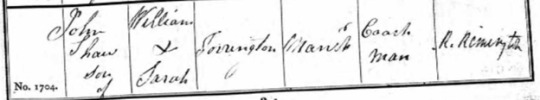

Maybe—because he wasn’t the only Shaw Torrington baptized on this day.

On a different page of the registry we find a record for one Esther Shaw Torrington. She was baptized the same day—December 10, 1826—and her parents were William and Sarah. William was a coachman, and while this time their surname was listed as Shaw Torrington rather than just Torrington, this is clearly the same family. That means John had a sister, but was she a twin? Or were they different ages, and one of them was hauled in when the other was born for a two-for-one baptism deal?

While I can’t find Esther’s precise birthday, her death record shows that she had to have been born after September 19, 1826 (she died September 19, 1878, age 51—she should have turned 52 that year if she was born in 1826, which means her birthday is later in the year). That means Esther was probably born sometime within a couple months before her baptism. If John were her twin, then he would have been 18 when he joined the Franklin Expedition and 19 when he died. While the age he gave to the Navy could be wrong—and subsequently, would be wrong on his tombstone—I’m inclined to think he was born a year before his sister and that the ages given in the Muster book and on his tombstone are correct.

Of course, that means we’re not anywhere close to narrowing down his exact birthdate. He was listed as 19 on May 12, when he signed up for the Franklin Expedition. For all we know, he turned 20 just days later, (although I like to think if he were that close to his birthday, they may have rounded his age up or indicated it somewhere). So the earliest his birthday could be is mid to late May, but what’s the latest date it could be? Technically, there could be as little as 10 months between John’s and Esther’s birth, which means that John could have been born in January 1826 (maybe February, if Esther were born in late November, but that’s kind of pushing it). This gives us a wide berth for his actual birthday, making it difficult to pin down.

Personally, I like to think he was born in autumn 1825, but that’s just speculation and wishful thinking (October would be the perfect month for the man whose frozen face would launch a thousand childhood nightmares of mine).

But if he were born in 1825, why wasn’t he baptized until December 1826? Were his parents saving up all their kids to get them baptized all at once? There was apparently such a thing as a baptism party, although those seem to occur when there are more than two children. Maybe Sarah and William liked the idea of baptizing all their children together. Maybe Sarah became pregnant with Esther only a couple months after having John, and they decided to wait when they realized they would need to do another baptism in several months’ time. Maybe they were just too busy when John was born to take the time to bring him to Manchester Cathedral.

Or maybe it was because William was being indicted.

The Lancashire Archives has a Recognizance of Indictment for one William Torrington of Manchester, coach driver, from June 15, 1825. I ordered a scan from the archives and transcribed it the best I could (adding in some punctuation for clarity). [UPDATE: There was a phrase I couldn't transcribe at first ("the said," spelled with a long s), but I've figured it out since and have updated the post.]:

“Lancashire to wit.

Be it remembered, That on the 15th day of June in the sixth Year of our Sovereign Lord George the Fourth [1825] of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, etc. William Torrington of Manchester Coach Driver[,] George Calvert same place Farrier and Esther Shane same place Widow [off to the side is written Mr. Norris/Morris, perhaps the name of the Judge] severally personally came before me one of the Justices of our said Lord the King, assigned to keep the Peace within the said County, and acknowledged severally to owe to our said Lord the King the said William Torrington the price of Forty pounds[,] George Calvert and Esther Shane twenty pounds each of good and lawful Money of Great Britain, to be made and levied of their Goods and Chattels, Lands and Tenements, respectively for the Use of our said Lord the King, his Heirs and Successors, if the said William Torrington shall make default in the Condition hereunder-written.

The Condition of this Recognizance is such, that if the above bounden William Torrington personally appear at the next General Quarter Sessions of the Peace, to be holden by adjournment at the Parish of Manchester, in and for the said County of Lancaster, and then and there to answer such Bill or Bills of Indictment as shall be preferred against him [crossed out from the typed form “for an assault upon”] and in the mean Time do keep the Peace and be of good Behaviour to our said Lord the King, and all his liege Subjects, [crossed out “especially towards the said”] then the Recognizance to be void, or else remain in full force.

Acknowledged before me William Torrington To answer [crossed out “for an Assault, etc.]”

Basically, in mid-June of 1825, William Torrington was arrested but released from jail, to return to court at a later date under penalty of a fine. A couple people he knew, George Calvert and Esther Shane, backed him up, promising to cover his expenses if he failed to reappear in court.

I have not been able to find information on why he was indicted—that information would most likely be in the Indictment Roll, which I would have to go through at the Archive itself, something made difficult with an ocean between me and Lancashire. It’s also possible that there is no further information available about William’s indictment, or at least none that has survived. I skimmed through the Lancashire order book for 1825 but didn’t find any mention of William or his indictment (with a closer reading, maybe I’ll stumble upon something). However, it’s possible that the case never went to trial, and that’s why it does not appear in the order book. And considering that he had a daughter the next year, whatever outcome happened clearly didn’t keep him out of commission for long

Whether or not his case went to trial, facing legal peril has a tendency to push everything else in life to the wayside, even the birth of a first child. Any fees that he may have incurred from the indictment and any related issues may have caused a temporary financial burden on William and Sarah, making it difficult for them to have John baptized. This is of course just one of many possible explanations for why John Shaw Torrington was baptized in 1826 and not in 1825, the year it’s assumed he was actually born, but we’ll probably never know the real reason.

And now, since I have written over 2400 words analyzing just Torrington’s baptism registry, I think I’ll bring this post to a close. Next up: what little we can piece together of his life growing up, before he joined the Franklin Expedition.

<<Back | Next >>

Torrington Series Masterlist

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of the Famous Black Canadians

On the topic of famous black Canadians, the first that often come to people's mind is Harry Jerome. As a matter of fact, Jerome was named as Mr. Canada and the fastest man in the world as well before Donovan Bailey or Ben Johnson. He's birthplace was in Prince Albert, Sask., and lives in Vancouver. He has taken part in 1964 Olympics and then won a bronze model, then two years after that, he snatched gold at the 1966 Commonwealth Games. Read more great facts on blacks in Canada today, click here.

Yet another popular black Canadian is Portia White. She's born in Truro, Nova Scotia. At a young age, she started singing for her father's African Baptist church choir and later performed as concert singer worldwide. By profession, she is a teacher in rural Halifax schools. Ms. White soon realizes her great potential with the support shown of Nova Scotia Talent Trust and the Ladies' Musical Clubs.

In Charlottetown's Confederation Center for the Arts in 1964, she is one of the acts that had opened it, which is also considered as one of her major appearances. This was also the same time when Queen Elizabeth II attended the event.

In this list, we also have Elijah McCoy who was born to slavery in Kentucky in Colchester but then escaped in 1843. While he has an engineering degree in Scotland, he wasn't lucky enough to get a job aside from a railway fireman in Canada.

Being a mechanic he is in 1870s, he soon noticed that machines should stop every time it needed oil. He devised a tool that will be installed to oil machinery and it was because of this, no machine or engine was considered complete unless it has a McCoy Lubricator.

William Hall made a history in 1857 for being the very first black Canadian sailor and also, the first famous black Canadian to be given the Victoria Cross. When he is just a teen, he decided to join the Royal Navy. Apart from joining the Royal Navy, he was additionally decorated for his bravery during Crimean War.

Mary Ann Shadd was another black Canadian and the very first woman publisher to ever exist in North America. She establishes the Provincial Freeman, which is an abolitionist newspaper along with Reverend Ringgold Ward in 1853. She was also born in Delaware in 1823 and then fast forward to 1851, she decided to move to Canada where she has opened an integrated school.

She survived the American Civil War and after that, she made up her mind to pursue her love and passion of teaching in the US and soon became the first woman to e0nroll in Howard University law school.

0 notes