#'60s

Text

Keith Moon

1963

#Keith Moon#The Who#classic rock#rock#hard rock#heavy metal#rock and roll#'70s rock#'70s#'60s#60s rock

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bob Dylan on stage at the Newport Folk Festival, 1964

#bob dylan#singer#songwriter#folk#blues#country#rock#folk music#blues music#country music#folk rock#rock music#rocknroll#rock n roll#rock'n'roll#rock 'n' roll#newport folk festival#1964#1960s#1960s music#1960's#1960's music#60s#60s music#60's#60's music#'60s

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

yep

#brian jones#'60s#1960s#golden stone#blues music#blues rock#the rolling stones#i love him sm#rolling stones#classic rock#60s music

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

____Michael Rougier, Japan, 1964.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

107 notes

·

View notes

Video

Bubble Gum Machine Pocket Knives by Darth Ray

Via Flickr:

Bubble Gum Machine Pocket Knives Miniature pocket knives collected in the '60s from Bubblegum Machines, Cereal Boxes, and maybe Cracker Jacks

#Bubble#Gum#Machine#Pocket#Knives#Bubble Gum Machine#Pocket Knives#Bubble Gum#Knife#Miniature#collected#'60s#Machines#Cereal#Boxes#Cracker#Jacks#Bubblegum Machines#Cereal Boxes#Cracker Jacks#flickr

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Installation view of From the Collection. 1960–1969. New York. The Museum of Modern Art. Photo. Gus Powell.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

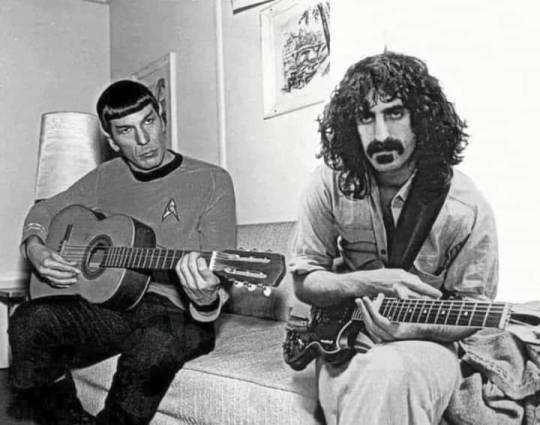

Mr Spock and Zappa

#Mr Spock#Leonard nimoy#Frank Zappa#Star Trek#classic rock#rock#hard rock#heavy metal#rock and roll#'60s#'70s

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

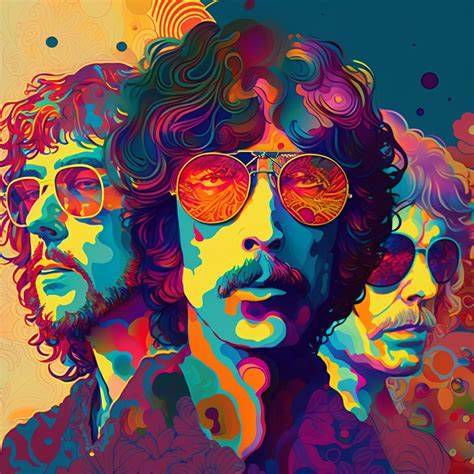

Jimi Hendrix, 1967

#jimi hendrix#rock#rock music#psychedelic pop#psychedelic music#hard rock#blues#r&b#1967#1960s#1960s music#1960s rock#1960's#1960's music#60s#60s rock#60s icons#60s music#60's#60's music#'60s#singer#songwriter#singer songwriter#funk rock

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Best Scooby Doo chase song in my opinion

#is it because i think being in love with an ostrich is code for a nonhetereonormative relationship? well yes but it still rules as a song#scooby doo#classic cartoons#'60s#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silvio Berlusconi che canta su una nave da crociera, anni '60

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

my generation, part 2

So much history, so much incident, and yet so little of substance has stuck in the collective subconscious of the Baby Boomers, let alone been carried forward by them. For thirty years, we have perceived ourselves, and encouraged younger generations to perceive us, as having been among the instigators of the ’60s ferment, those in whom its unarguable revolutionary and creative energies — not to mention its elusive ideals — coalesced, and yet our memories of that decade are remote, vaporous, and not quite real.

Most of us were too young to have been anything other than spectators in the early ‘60s, despite the saunter we feign now in late middle‐age as survivors and faux‐savants. True, we had been among the casualties at Kent and Jackson States, at Berkeley and several other American universities. We had been roughed up and arrested by police in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. We had even hurled rocks and Molotov cocktails beneath clouds of noxious tear‐gas on the streets of Paris, Rome, Prague, Belfast and London — or of Watts, Hough, Detroit and Newark, where those of us who were black had come under fire from police and National Guards during bloody race riots between 1965 and 1967. In the end, though, they were not our battles. They belonged to the Silent Generation. We lent our support, if we were old enough, but we were on the periphery of most of the struggles, and our understanding of what was really at stake — however genuine our sympathies — was often incomplete.

Instead, we watched on television, and listened to the soundtrack on our record-players. We read eye‐witness accounts in Rolling Stone.

A generation born and raised in peacetime, during a prolonged period of economic well‐being (even in Europe, thanks to the billions invested by the USA under the Marshall Plan), Baby Boomers had no more certainty than the previous generation — forty years on, I sometimes relive the visceral chill of a seven‐year‐old’s terror of The Bomb: cowering with other children under desks during a Los Angeles school drill for a nuclear attack, air raid sirens wailing in the streets — but we were less inclined to hold strong beliefs, let alone agitate for change. We learnt to adjust, to be fluid, to “go with the flow”. In our mediated, proto‐virtual understanding of the world, everything was, and still is, fungible.

We dreamed instead. More than any previous generation of the twentieth century, Boomers had been raised amid the constant white noise and screen clutter of increasingly ubiquitous mass information, entertainment and communication media. By the late ’60s, the counter‐culture already had its own media, including magazines like Rolling Stone, New Musical Express and Creem, and aspects of it — all necessarily youth‐oriented — were being assimilated by the mainstream through films, TV and advertising. Gradually, we came to believe that these same media, with their McLuhan‐esque seductive power and their apparent free flow of images, information and ideas, rather than protest and confrontation, were the key to building the new world of our imaginations. It’s a notion borne out by the flood of Baby Boomers — among them Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Timothy Berners‐Lee (all born in 1955) — who, since the late ’70s, have nourished an age of technological invention to rival the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, even if a genius comparable to Tesla or Edison is less apparent.

Baby Boomers preferred the surface of things, the context rather than the content. We were easily distracted. We grew up with the passive, low‐level attention required by ‘old’ electronic media such as TV, radio, film and recorded music to reading — one of the few things we still have in common with other, younger generations. We wanted easy access and the ability to switch between content (we already called it channel surfing) whenever our attention lagged — which was more often than we liked to admit.

Well before the benign effects of the early ’60s counter‐culture seeped into the community at large, we were drawn less to its ideals than to its image. For us, the medium wasn’t just the message: it was everything. For the rest of the century, the Baby Boomers’ unconscious reverence for Marshall McLuhan’s contention that a medium affects society not by the content it delivers, but by the characteristics of the medium itself was evident everywhere. The best entertainment (and advertising) for Boomers was, to use McLuhan’s own jargon, hot or data‐plenty, demanding less concentration but delivering ever‐greater effect. Social protest gave way to the profane. Rock concerts became ‘shows’, each an extravagant gesamtkunstwerk with complex staging and lighting. No longer happy to stand in one place and just sing or play as older performers did — even Elvis, who insinuated the snakey promise of hillbilly rutting into middle America’s subconscious, was still pretty tame — band‐members turned manic and feigned sex with a Fender Stratocaster guitar (or a half‐naked fan), destroyed a wall of speakers, or bit the head off a live chicken before swan‐diving into the crowd. Vinyl LPs were no longer two twenty‐minute sides of discrete, three‐minute songs, but multi‐disc concept albums that were almost Wagnerian in duration and structure.

The Boomers’ preoccupation with scale and spectacle at the expense of nearly everything else became apparent in other media. Steven Spielberg — born in 1946, the first of many successful Baby Boomer directors — turned his back on the sort of smart, unsettling, contemporary character‐driven dramas directed by Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Bob Rafelson, Martin Scorsese and others that had revitalised American cinema during the late ’60s and early ’70s to create Jaws, a film in which the main ‘character’ was a man‐eating shark, and any semblance of coherency in the narrative was subsidiary to the gradual amplification of suspense and the timing of set‐piece action sequences. Jaws was the first ‘blockbuster’ (a word only a Baby Boomer could love, meaning then a big‐budget Hollywood production that grossed over $US100 million in revenues in the United States alone). More importantly, it was a watershed in the entertainment industry’s perception of what the mass audience really wanted — excitement, the more intense the better. With uncanny intuition, honed during a decade of almost obsessive fascination with cause and effect in a variety of media, Baby Boomers knew how to give it to them.

It didn’t take long for this talent to be adapted as a means of exerting greater control. If the Silent Generation had been raised during times when the whole concept of control, let alone the means to exert it, must have been impossible to imagine – a sense of impotence was yet another compelling motivation for it to try to demolish the rickety postwar social order and establish something in which it could have some say — the Baby Boomers understood (as did the Roman Emperor Titus when he completed the Coliseum in 80BC and ordered that it be used for gladiatorial combat) that attention was a form of currency: acquire enough of it and you could transform it into real capital — which, in turn, gave you power.

And what better way to gain attention than by gaining the upper hand in entertainment media? It was an idea that would come into its own during the ’90s technology boom, when Generation X entrepreneurs, in harness with Boomer venture capital, would use the equation to leverage unimaginable value for their development of a new medium, the world wide web, inverting the idea of using fixed programming to capture the passive attention of a faceless mass audience of millions — the measure of value in old media — to create something a great deal more valuable, an infinitely customisable, two‐way interaction with a million‐fold audience of just one.

Control was — and still is — a big driver for Boomers. It underscored our relationship with the rest of the twentieth century, during which we tried to impose our views on others and to regulate their social and sexual behaviour with a zeal that smacked of a new Puritanism. We were stricter with our children, giving them less leeway to make their own decisions than our parents gave us. We were more ready to get involved in their education, or in any other area where we thought we might be able to exert influence on the shape of their lives. (To give us the benefit of the doubt, maybe we figured that if we didn’t, television would do it for us.)

The first of the Boomer legislators, judges and prosecutors were a lot less sympathetic and humanist than those of previous twentieth century generations. They were almost eager to limit or dispense with inconvenient legal and civil rights, impose stiff sentences or resort to the death penalty. As for Boomer politicians, if the Bush and Blair governments are anything to go by (their Silent Generation deputy, John Howard, could be said to be ‘aspirationally younger’), they are conservative, pragmatic, unethical, secretive and suspicious of free speech. They don’t much like the idea of a free press, either. Even if they are not as malignant as Bush, Boomer politicians can be little more than artful constructs (the former New South Wales premier, Bob Carr, springs to mind): a shiney, media‐friendly façade, a few well‐ turned, anodyne phrases and a lack of real empathy. All Boomer politicians have tried to cloak their legislative forays into social engineering as timely, well‐intentioned ‘modernising’ of existing political and social frameworks, but their version of modernity is always more intrusive, restrictive and careless of our rights.

There have been several Boomer political leaders who have tried to adhere to a more liberal, pluralistic and inclusive social philosophy, but there appears to be among them a disturbing propensity to engineer their own failure — as the former Australian Federal Labor party leader, Mark Latham (an on‐the‐cusp Boomer), appears to have done — or to self‐destruct. William Jefferson Clinton, the first Boomer to be elected President of the United States, and arguably one of the most intelligent and charismatic men to have occupied the Oval Office, ended up betraying the expectations of his generation because of a shallow preoccupation with what can only be described as ‘surface effect’, a disquieting moral ambivalence, and a tendency to self‐indulgent excess and hubris that are archetypal of our generation’s flaws.

At the edge of politics, straddling faded dividing lines between church and state, Boomers are among the most vociferous proselytisers not only for Christian fundamentalism — what better way for Boomers to exert control than through a belief system that behaves like an entertainment medium? — but, it might also be argued, for Islamic fundamentalism as well (Iran’s Islamic President Mahmoud Ahnadinejad, born in 1956, and Osama bin Laden, born a year later, are notable examples). Whatever side of the political, religious or cultural fence they’re on, Baby Boomers have a predilection for dogma that stems from their discomfort with — and inability to control — the confusion and contradictions of the times through which they have lived.

Even before the last Baby Boomer came of age — at eighteen, not twenty‐one, entitled to vote and drink — we had stepped out of the long shadow of the Silent Generation, looking for the main chance. We were never really idealists: we were — and still are — innately selfish and cynical (if not downright hypocritical). We focus on achieving a semblance of order, of control — we like to get the façade just right — in the context of right now, but we tend to overlook what it might cost us in the future. The idea that just because something can be done doesn’t necessarily mean that it should doesn’t occur to Boomers. Maybe it’s another indication of our hubris, but we don’t waste much time thinking about consequences.

The Magic Christian, a film directed by Scotsman Joseph McGrath, was released in 1969, the same year as Easy Rider. Adapted by the American satirist Terry Southern from his novel of the same name — Southern also cowrote Easy Rider with its stars, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper — The Magic Christian was an absurdist comic fantasy starring Peter Sellers as Sir Guy Grand, an Englishman of egregious wealth and a wicked sense of irony. Grand adopts a naïve, homeless young man, played by The Beatles’ drummer, Ringo Starr, to be his heir, renaming him Youngman Grand. He instructs Youngman in the operation of the “family business”: exposing and exploiting in most lurid ways the unquenchable greed of everyman. In one of the film’s funniest — if least subtle — moments, Sir Guy fills a swimming pool with excrement and tens of thousands of dollars, then invites passers‐by to retrieve as much money as they want. Soon the pool is overflowing with people fighting each other for fistfuls of cash as they struggle to keep their heads about the foetid shit, all under the gaze of a bemused Sir Guy and a troubled Youngman: “Grand is the name, and, uh, money is the game. Would you care to play?”

Indeed we would.

Film supplanted literature in the late ’60s (if not comic books, which we reconceived as ‘graphic novels’ to market them to a younger generation) as the repository of all our myths and parables. The medium appeals to restless Boomers because it enables us to rework these narratives from time to time. Eighteen years after the premiere of The Magic Christian, Sir Guy and Youngman Grand were transformed into Gordon Gekko, a rich and ruthless corporate raider (played by a middle‐aged Michael Douglas), and Bud Fox, a young if not‐so‐innocent stockbroker Gekko sets out to corrupt (a still fresh‐faced Charlie Sheen), in Wall Street, American director (and Baby Boomer) Oliver Stone’s celluloid eulogy over the fresh corpse of a decade notorious for its avarice and self‐interest. Boomers don’t like to acknowledge it any more (maybe, in part, because it reminds us of just how old we are now), but the ’80s were our best of times. The stern, Boadicea‐like Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, and the doddery, paternalistic B‐movie actor and pretend‐cowboy, Ronald Reagan went out of their way to reassure us that the worst aspects of our generational character, the very traits that still grated on the Silent Generation, were not just OK but desirable in a world in which old‐fashioned values like ambition, self‐interest, wealth, privilege, heartlessness — oh, and empty‐headed celebrity — had made a comeback. The decade’s bible (or, as another writer would have it, Yuppie porn), was Vanity Fair, a glossy magazine edited by the Baby Boomers’ own brainy It girl, Tina Brown.

Even the collapse of the stockmarket on October 19, 1987 — so‐called Black Monday, when the New York Stock Exchange suffered its steepest‐ever one‐day decline and stripped the Dow Jones Industrial Average of nearly a quarter of its value (by the end of the month, the Australian stockmarket had lost over forty per cent of its value) — couldn’t deflate our confidence. Within a decade, Boomers would set in motion another bubble in stockmarket values, this time partnering with tech‐adept geeks of Generation X — our myriad neuroses and obsessive compulsive tics an unlikely match with their tendency to Attention Deficit Disorder and Asperger’s‐like syndromes — to conceive a New Economy, an alternative system of values underpinned by an entirely new medium of communication, information, interaction, transaction and entertainment.

It was a quartet of Silent Generation scientists at the US Defense Advance Research Projects Agency — Lawrence Roberts, Leonard Kleinrock, Robert Kahn and Vincent Cerf – that developed the technology and architecture to interconnect remote computer networks and thus create the internet, although it was a Baby Boomer, Timothy Berners‐Lee — an Englishman working at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (better known as CERN) – who came up with something he called the world wide web. The far‐reaching revolution inherent in Berners‐Lee’s creation was at first lost on his peers (including the hyper‐intelligent head of Microsoft, now the world’s wealthiest individual, Bill Gates), so it was left to a younger generation — the Xers, whose very namelessness reflected a disconsolate sense of being a generation adrift, disenfranchised from a mainstream economic and cultural agenda now dictated (or, more accurately, obscured) by Baby Boomers — to recognise the liberating possibilities of the web’s capacity to interconnect not just documents — text, static images and, later, sound and video — but also ideas.

The Boomers were never big on originality. We were, after all, the generation that invented technology to make the appropriation or ‘sampling’ of anything as simple as a few keyboard strokes on a computer. We were good at refining existing ideas — the World Wide Web was a case in point, so too were the first iterations of Microsoft’s DOS operating system — but what we were, and still are, best at was hype. Our aptitude for effect — the gesamtkunstwerk of those ’60s rock shows — allied to our almost forensic absorption of mass media over the previous forty years meant that we were well prepared for the ’90s dot.com boom. Most of us were less interested in the web’s technology than we were in devising its business models (where, almost instinctively, we sensed the real power would be) and articulating the precarious value equation that turned attention into cash. Nonetheless, the early years of internet entrepreneurism were the apotheosis of the Boomer generation. Too bad that they resurrected in us an ethos that had tainted us during the previous decade — excess in all things, especially greed.

In Wall Street’s best‐remembered scene, Gordon Gekko confronts the restive shareholders of the fictional corporation, Teldar Paper, to convince them to sell off the company’s assets. With the fervour of a TV evangelist leading his congregation in prayer, Gekko tells them: “Greed ... is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind and greed, you mark my words, will not only save Teldar Paper but that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA.” This wasn’t just another of those cinematic moments that resonated briefly in the media‐sensitised subconscious of Baby Boomers before receding into the ambient low‐frequency noise. Gekko’s words became our mantra (Greed is good. Greed is right. Greed works.) They permeated our attitude for the next twenty years.

The irony is delicious: Baby Boomers turned out to be the Sir Guys for at least two generations of Youngmans.

Part two of three.

First published as part of a single essay in Griffith Review, Australia, 2006.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

51 notes

·

View notes