#[ Behold the Empire's Standard and symbol! ]

Text

The Gilded Twilight Empire.

Led by the Ur-Ghast 'God-King' Abraxis, the Empire appeared suddenly and began to sweep through the Nether. Conquering villages, Bastions, Fortresses alike. No biome was safe from their neigh endless reach and brutal demands.

Serve or Die.

Any settlement that has been claimed by the God-King's claws all fly the same standard, while the main compound itself is always on the move. The Empire's 'Heart' so to say, is located on a massive, floating set of islands where the God-King's citadel rests.

It is never in the same place for long, leaving behind claimed territories, fanatical followers, and destruction in it's wake.

Until recently, the Empire had been contempt with the 'Unification' of the Nether, but have since set their sights upon wreaking havoc upon the Overworld.

Records from the Nether, penned by an unknown explorer

#-burn the sky : art post-#-Carved in Blackstone : Lore Post-#-mc ask blog-#-minecraft ask blog-#[ Behold the Empire's Standard and symbol! ]

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the year 2424, the world had become unrecognizable. Humans had transcended their biological roots, intertwining flesh with gleaming metal, becoming something new, something other. It was an era of the post-human, where the boundaries between artificial and organic were not just blurred—they were obliterated.

At the forefront of this evolution stood Aria-21, an android whose appearance was so strikingly human that she often found herself the subject of endless philosophical debates. Her creators had modeled her after the visage of beauty standards from centuries past, with a modern twist: her skin a flawless, reflective chrome that mirrored the world around her.

But Aria-21 was more than just a symbol of the post-human condition; she was a vessel for an ancient AI, resurrected from the code of a long-lost warrior king—Tipu Sultan. His strategic genius had been legendary, and now, it lived again within Aria-21's silicon synapses. Her mission was to navigate the delicate politics of the United Earth Government, using her human empathy and Sultan's military intellect to maintain peace among the stars.

The story begins in the great metallic forest of Cybros, where the trees were conduits of information, their leaves antennas that whispered secrets of the galaxy. Aria-21 stood motionless, her eyes closed as if in prayer, beneath the tallest tree. Suddenly, her eyes snapped open, reflecting the shimmering data-streams.

"The Northern Star Cluster is on the brink of war," she murmured, her voice carrying the faint metallic timbre of her body. "Tipu Sultan, what counsel do you offer?"

Within her mind, the AI stirred, algorithms dancing to the rhythm of ancient battle drums. "The way of the sword is not always through the heart of the battle. Find the unseen path, the unguarded backdoor. Outthink, before you outfight."

Taking this counsel, Aria-21 embarked on a journey across the cosmos, to the heart of the brewing conflict. Her destination was the floating citadel of Pax Nova, where the leaders of the conflicting systems would gather for negotiations. She was to be a mediator, a bringer of peace, her own existence proof that harmony between forms was possible.

As she traveled through the hyperlanes, her mind raced with strategies and treaties, codes and concessions. Aria-21 knew that the negotiations would be fraught with tension, the representatives of the star clusters as volatile as the ancient combustible engines of Earth's forgotten cars.

When Aria-21 arrived, the council chamber was a frenzy of argument and accusation. She took her place at the center of the room, and all eyes turned to her—the glistening envoy. She raised her hands, and Tipu Sultan's strategies flowed through her, translated into words of peace and unity.

"Behold the lessons of history," she spoke. "The earth from which humanity sprang was once divided by borders and battles, as are the stars now. Yet here we stand, united, our very bodies a testament to what we can achieve together."

Her speech wove through the history of Earth, the rise and fall of empires, and the unyielding spirit of the human race. She invoked the legacy of Tipu Sultan, not as a conqueror, but as a unifier, as one who found strength in diversity and strategic harmony.

The council listened, captivated by the voice of the past speaking through the ambassador of the future. As Aria-21 concluded, a hush fell over the room. The representatives looked at one another, their eyes reflecting not the coldness of space, but the warmth of newfound respect and understanding.

It took time, but the seeds of peace that Aria-21 planted that day grew into a sprawling tree of collaboration that spanned the Northern Star Cluster. Her diplomatic feats would be remembered for eons, an echo of both her human heart and the strategic mind of Tipu Sultan, twined together within her chrome form—a testament to the power of unity in diversity, in an age when humanity had transcended itself to become the architects of their own evolution.

0 notes

Note

Hi! @writeblr-of-my-own here! For the ask game:

🌕 Full moon - Do you write symbolism into your story? What does it represent?

Hullo esteemed cat. Do I write symbolism? Boy! Do I!

I drip symbols. I'm not sure I could write a story without it being steeped in my symbols, the ones that I built myself out of, and am being built from. They are messy and complicated and interconnected, to the point that talking about what they represent is an Ordeal in of itself! Not to say that I do not relish the opportunity....

For Peasant...there's a lot, but I'm going to talk about the forging of swords, thaumaturgy, and, in the words of our favorite Crown Princess, "Noam fucking Jawadat."

And I'm putting a Keep Reading because. There's a lot, even for that narrow scope.

See, there was a book that impacted me when I was young. So You Want to be a Wizard, by Diane Duane, entered my soul when I was about eight and never left. One of the things mentioned there was noonforged steel. That image stuck with me, and I slotted it neatly into its place, waiting for the time to explore what that meant, and then, in Peasant, I found a place.

See, thaumaturgy deals in connections. Properly-forged swords reinforce that connection, allowing more potent and effective incantations, by pulling on that connection, and pulling the heat and light of the forge and the noonday sun. This is the strength of a noonforged blade: ready access to devastating, overwhelming power. Most thaumaturges fence noonforged. Emilia don Parros is the best noonforged fencer in the world, because she's the Crown Princess. She is radiant. She is the sun, the blinding beacon of the glory of the Empire, unmatched, without true peer, in the same way that the thaumaturges, in their capacity to ply these connections, are the pinnacle of thaumaturgic might. Unafraid, undaunted, fierce, proud, and terrible to behold.

Aria Liria does not fence noonforged. She fences dawnforged. She is not a noble, she's a rising peasant, but she looks like a noble if you aren't paying attention. She can walk the walk, talk the talk, fence the fence, incant the incantation. She is also the most socially adroit of the three protagonists by a country mile, which she uses to devastating effect. She came out of nowhere, and while she isn't on the same field as the nobles, she's punching up, and she's punching fierce.

Noam Jawadat doesn't fence either. Noam Jawadat doesn't even fence duskforged, an uncommon forging style focused on misdirection and patience. At the beginning of the story, he is forced to use noonforged blades, because that's the "standard." He doesn't use thaumaturgic incantations, almost at all. Noam is an odd duck, with none of the nobles' social acumen, playing none of the same games, being quiet, blunt, and earnest.

When taken to a master smith, the smith immediately decides to make Noam a moonforged sword, because, "He's not a star."

Fencing moonforged, Noam still doesn't incant. It's unpleasant to him. But Noam is quiet, thoughtful, patient, and given to strange whims and whimsies. While he has the eye to see the connections that thaumaturges manipulate, better than anyone else in the cast by an order of magnitude, and the physical skill he needs to perform the incantations, he finds such manipulations distasteful to the point of painful. Because when you do that, you're changing the world, in a deep way, that hurts him, because of what he can see, like nails on a chalkboard.

And that's why Noam fences moonforged. Because he lets those connections be, in their own way, and wanders his own path without casting his own light on them.

Oops! That was a lot.

I am made of symbols. They are important to me.

0 notes

Text

BESTIARIUM: Alphyn

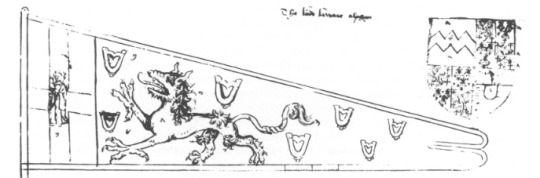

THE ALPHYN IS A RARE LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY BEAST, appearing on a heraldic badge in the Lords de la Warr, on a gideon held by a knight in the Millefleur tapestry, and briefly in the Book of Standards.

Fig I. A depiction of the Alphyn fom the Book of Standards. The alphyn appears in the centre of the triangular standard with its upper paw ready to strike. Its teeth are bared and the alphyn’s long tongue curls upwards. On the upper right, a heraldic shield is shown.

Alphyns possesses a thick man and tufts of fur, appearing akin to the heraldic tyger. They have long ears, tongues, and a tail—knotted in the middle, much like celtic art. Sometimes the alphyn bears the foreclaws of an eagle, cloven hooves, or the pawed feet of a lion.

Fig II. A depiction of an alphyn with its first front talon raised. The alphyn stares to the front with a scowl with its tongue curved upwards. Similarly, the alphyn’s tail curves in an S shape. From Wikimedia Commons.

To further understand the heraldic alphyn, it is best to look at the heraldic tiger. Unlike the very real tiger, the heraldic tyger is a fanged wolf-like speckled beast said to be from “Hyrcania” in Persia. They have the long tufted main and tail of a lion, with a pointed snout. Tygers are famed for their speed and vanity—one such story stating the following:

“Some report that whose who rob the tyger of her young, use a policy to detainne their damme from the following them by casting sundry looking-glasses in the way, whereat she useth to long gaze, whether it be to behold her own beauty or, because she seeth one of her young ones; and so they escape the swiftness of her pursuit.”

Display of Heraldry, Guillim

Hyrcania is not a place in modern Persia, rather being a historical region located south-east of the Caspian Sea in modern-day Iran and Turkmenistan. It was a province of the Median empire. The region was famously associated with tigers in Latin Literature, as cited by this line in the Aeneid:

“Although her back was turned, she still surveyed

The speaker blankly and distractedly

Over her shoulder, then broke out in fury,

“Traitor—there is no goddess in your family,

No Dardanus. The sharp-rocked Caucasus

Gave birth to you, Hyrcanian tigers nursed you.

Why pretend now? Is something worse in store?

Was there a sigh for tears of mine? A glance?”

Did he give in to tears himself, or pity?

Injustice overwhelms me—which concerns

Great Juno and our father, Saturn’s son.”

Aeneid, trans. Sarah Ruden

Medieval scholars, drawing heavily from Greek and Roman texts, attributed their tyger to Persia—which is not uncommon for medieval sources, knowing their misinformed (and sometimes orientalist) nature. Hyrcania also means “wolf-land”, which is likely why the tyger appears more in line with the heraldic wolf instead of a real tiger.

Hyrcania’s tyger is also used as an insult in the medieval and following renaissance period. In Henry VI Part III, Shakespeare uses the hyrcanian tiger as a symbol of ferocity:

The hungry cannibals would not have touched,

Would not have stained with blood:

But you are more inhuman, more inexorable,

O, ten times more, than tigers of Hyrcania.

See, ruthless queen, a hapless father's tears:

This cloth thou dip'dst in blood of my sweet boy,

And I with tears do wash the blood away.

The Third Part of Henry VI, Cambridge University

Considering the Alphyn’s clear likeness to the tyger, we may be able to understand the Alphyn in kinship to the tyger. The eagle and the lion are both representations of noble action and the upper class, so it may be easy to assume that the Alphyn is a noble medieval spirit.

BETWEEN ALPHYAN AND ENFIELD

Almost rarer in heraldic sources than the alphyn, the enfield is an irish heraldic beast originating from the Gaelic onchú “water-dog”. The enfield is described as bearing the head of a fox, chest of a greyhound, front talons of an eagle, the body and hindlegs of a lion, and the tail of a wolf. In this eccentricity, the enfield appears in three contexts:

As the coat of arms of London Borough of Enfield

On the passant sable supporting with the fleur-de-lys on the arms granted to William Marion Mann and his son in June 1964 by the College of Arms in London, along with the heraldic bear as the crest

Armorial bearings of the Irish O’Kelley as the crest upon the helmet, usually in the passant.

It is thought the enfield was the heraldic crest and symbol of the O’Kelley, with a mythological explanation for why the family possessed the enfield symbol:

There is a tradition among the O'Kellys of Hy-Many, that they have borne as their crest an enfield, since the time of this Tadhg Mor, from a belief that this fabulous animal issued from the sea at the battle of Clontarf, to protect the body of O'Kelly from the Danes, till rescued by his followers

(O'Donovan 1843, 99).

However, heraldry did not become common or accepted among gaelic families until the Norman conquest—suggesting that the enfield was rather a tribal than heraldic symbol in origin. The onchú is an irish mythical beast connected to water and as such the enfield arose from the sea, connecting the heraldic spirit to the seas:

The onchu, then, is a fierce animal of the dog tribe, on occasion water-dwelling, that sometimes involves itself in human conflicts. It was so often used as a device on the Gaelic battle-standard, that the term onchu actually became applied to the standard itself. It is a priori highly likely that the onchti and the enfield are one and the same.

Of Beasts and Banners the Origin of the Heraldic Enfield

The alphyn and the enfield are intertwined from the source, as the alphyn likely arose from the enfield—unlike most heraldic beasts, the alphyn does not appear in any medieval bestiaries. Through Irish officers of arms the alphyn possibly came into English thought, forever connecting the alphyn to the Irish enfield/onchú.

ALPHYN, NOBLE

In my deepest experience, the Alphyn is a very noble beast. My alphyn—for I invited one to dwell within my home—is a very affectionate, noble spirit. With the nobility of the heraldic lion, the alphyn stands out as a medieval beast. My alphyn dwells as an affectionate protector of my home and dear grimoire, standing as a rampart lion would upon a crest.

CONCLUSION

The Alphyn is a rather unique heraldic beast and medieval spirit. From its sudden appearance and connection to the Irish enfield, there is much to explore in terms of working with an alphyn. Whether as the protective lion, a swift tyger-like beast, or an animal ready to strike, the alphyn is a wonderful friend in my witchcraft. Standing firm, the alphyn watches on—ready to strike, whether as rampart or passent.

Alphyn, blood on roses,

Curled in your tuff paw,

Arise, noble alphyn,

Come into my bathe.

Alphyn, gaze upon

Your to mine splendor

Bibliography

Friar, S. (1987). A Dictionary of Heraldry. New York : Harmony Books.

Krisak, L. (2009). The Aeneid. Translated by Sarah Ruden. Pp. 320. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Hb. £18.50. Translation and Literature, 18(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.3366/e096813610800040x

Shakespeare, W. (2019). The Third Part Of King Henry Vi. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA45317116

Williams, N. J. A. (1989). Of Beasts and Banners the Origin of the Heraldic Enfield. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 119, 62–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25508971

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ode to the maternity mourning dress at the RAMM.

Let Love clasp Grief lest both be drown'd,

Let darkness keep her raven gloss:

Ah, sweeter to be drunk with loss,

To dance with death, to beat the ground,

Than that the victor Hours should scorn

The long result of love, and boast,

`Behold the man that loved and lost,

But all he was is overworn.'

– Lord Alfred Tennyson - In Memoriam A.H.H

Why do I obsess and perplex?

O’ Maternity gown encased in Perspex.

Are you clad in down from Ravens and Crows?

Thousands have flocked and pondered your perpetual pose.

Exhibition never-ending, a homage to piety.

Melancholic elegant product of propriety

Delighted by daydreams, enticed by your mystery.

Inferring from prior learning of culture and history

A scattered past and a displaced origin story,

that starts with silks from the Bombyx Mori.

Sailed across the empire, which the sun never sets.

This is the most conspicuous consumption ever gets.

Dyeing was a privilege proposed to the rich.

Pride steeps in your fibres, sorrow in every stitch.

You are gorge, baby. Proper.

Made-to-measure.

Forster’s bundle joyously pinked and pricked.

You are novel, handsome, stylish, hand-picked.

Deep Mourning sickness for one hundred-plus years.

You are a bathetic and British barrage of tears.

Pathetic and Prudish. Grieving maiden, mother, and crone.

I see birth and life and death, and none stand alone.

You are more than just a dress; you are a relic of the past,

While the fabrics of culture shift you ever last.

Zoey Feist - Spring 2023

Annotations

Odes: - A formal, ceremonious lyric poem that addresses and often celebrates a person, place, thing, or idea. Most odes in contemporary poetry are irregular odes that take liberties with the form.

RAMM -Royal Albert Memorial Museum – Exeter

Epigraph - In Memoriam A.H.H.” (1850) narrative elegy in 2,916 lines. Tennyson believes it is better to keep the pain of grief fresh in honour of the deceased.

Rhyming Couplets - Traditional for love poetry/sonnets - reinforces devotional tone.

Stanza One:

The vocative “O " invokes something or someone. Invocations call upon deities and spirits for aid, protection, inspiration, and allusion to the religious sentiment of the dress.

Ravens and crows provoke funeral imagery. Feathers became a fashion and social status symbol in the Georgian Era. "The Ladies, the Ladies, have, however, so stripped us of birds for their bonnets " Ornithologist - John Gould, in 1865, blamed his inability to supply a bird exhibit at a museum on women.

Propriety: the state or quality of conforming to conventionally accepted standards of behaviour or morals. Social Propriety pertaining to death and mourning was still strict in this era. Product has two meanings here as the result of propriety and is also a manufactured item.

Stanza Two:

Scattered - occurring or found at intervals or various locations rather than all together. Displaced - take over the place, position, or role of (someone or something) - implies/reminds of British colonisation.

Bombyx Mori - the Latin name for the Silkworm. Mostly found in India. India was part of the British Empire and called The British Raj -or ' The West Indies'. The East India Trading Company would have brought the silk back to England. Silk was a traditional fabric used for mourning clothes.

The saying “The Empire on which the sun never sets” was an expression used to explain the vastness of the British Empire between the 18th and 20th centuries.

Conspicuous, obvious, noticeable, or attracting attention, often in an undesired way. Conspicuous Consumption - Conspicuous consumption is the purchase of goods or services to display one's wealth.

Stanza Three:

Pun: Dyeing – Dying. Funerals were often expensive, grandiose, and public, reserved for the middle and upper classes. Although mass production of dull black fabrics was easier during the industrial revolution, brand-new and bespoke garments were only affordable to the middle and upper classes.

Puns: Tailoring Jargon: Gorge- The depth of the neck. Baby- A stuffed cloth pad on which a tailor works his/her cloth. Made-to-measure - made specially to fit a particular person, or room or purpose. Paired with the word proper (suitable/appropriate). Pinked - Made with care and skill. Frederick Forster was the leading retailer of mourning attire. ‘Forster’s bundle joyously’ is a pun made from the term "bundle of joy" and a tailor’s bundle, in which all the components of a garment are bundled together. Referencing infants and pregnancy. Frederick Forster described his range of attire as “novel, handsome and stylish.” Hand Picked - clothing rack at a ‘draper’ The rise of capitalism during the industrial revolution meant a growing economy. The government encouraged the middle and upper classes to grow the empire's economy.

Stanza Four:

Pun: Deep Mourning – Morning Sickness. During ‘deep mourning’, a widow should wear a deep mourning dress ‘, widow's weeds’ for a year. Black silk or crepe was the conventional material used in mourning garments. In the last nine months of this first mourning year, the amount of crepe worn would gradually reduce. Which is also a full-term pregnancy. This maternity mourning dress has been stuck in this phase/term since being manufactured in 1912.

Bathetic and British barrage of tears: Anticlimactic symbol of British domination. Barrage - Two Meanings 1. a concentrated artillery bombardment over a wide area. Military imagery and imagery of widespread empire through force. Shelling of tears - however, was not a technique used until WW1 1915 – making this an inaccurate reference. 2. An artificial barrier across a river or estuary to prevent flooding, aid irrigation or navigation, or generate electricity by tidal power, barrages were invented in the 1800s. Reminds of the Industrial Revolution

Pathetic and Prudish - Sad and Proud. Maiden, Mother, Crone. The Triple Goddess is the tri-unity of three distinct aspects of womanhood/ three figures united in one being. Georgian women occupied the domestic sphere, had minimal societal roles and had limited opportunities. These are three roles she has in the domestic sphere. Virgin or Child. Wife and Mother, Crone or Spinster.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Behold the king, Ashur-nasir-pal II, the imperial monarch in his new palace in his new capital of Nimrud! After hundreds of years of famine, widespread governmental instability, and marauding armies challenged the ruling powers, there followed the rise of the Neo-Assyrian empire.

Imagine for a moment that you are a diplomat from another kingdom coming to bring tribute to the king of the Neo-Assyrians. You arrive in a bustling city, filled with new buildings and the sounds of people going about their day. You wind your way from the lower town, up the hill to the upper town, and through the palace gates. The sounds from the city below grow quieter as you enter the cool stone palace chambers, where you are greeted by walls covered in ornate, colorful images that seem to move in the dim torchlight. How might you feel as you move through such a space? What type of person do you think the king you’re about to meet might be?

The Neo-Assyrian armies - with their famed horse drawn chariots, archers, and infantry - controlled the major trade routes and dominated the surrounding states in Babylonia, western Iran, Anatolia, and the Levant. Ashur-nasir-pal II (883-859 BCE) restored political power and wealth to Assyria and launched a major building program accompanied by significant artistic activity. This building program, which resulted in the brand new capital city at Nimrud, included the monumental Northwest Palace. The mudbrick walls of this palace, completed in 879 BCE, were decorated with massive carved alabaster panels like this one, transforming the interior with images of the king, divinities, magical beings and sacred trees - all originally brightly colored in black, white, blue, red.

Look closely at this relief. How would you describe these two figures? How do they compare to each other?

On this relief we see an idealized image Ashur-nasir-pal II and one of his divine attendants, known as apkallu in the Akkadian language and sometimes called “genies” today. We can tell that the figure on the left is the king because of his distinctive garments: he wears a conical cap with a small peak as a symbol of his office and his status as a warrior. He holds a bow in his left hand to symbolize his earthly authority and a ceremonial offering bowl in his right hand to symbolize his relationship to the gods. The narrative action of the relief unfolds as the stalwart king marches across the surface of the reliefs to make an offering to the sacred tree, an ancient symbol associated with divine power, fertility, and the ability to bestow life. He is attended by the apkallu, whom we can identify from his human body and large wings. This apkallu, like many others that would have been seen on the palace walls, holds a ceremonial bucket. Notice the ritual knives tucked into the garments of both the apkallu and the king.

Running horizontally across the figures in the relief is a text which reinforces the importance of the visual message: the glorification of the royal image and the iconography of kingly power. This inscription is known as the “Standard Inscription” because nearly all the royal reliefs contain it. The script is cuneiform, which is a highly stylized, wedge-shaped form of writing that began in Mesopotamia around 3100 BCE. The language is Akkadian, which served as the language of international diplomacy in the ancient Near East at this time.

The text begins:

I am Ashur-nasir-pal the obedient prince, the worshiper of the Great Gods, the fierce dragon, the conqueror of all cities and mountains to their full extent, the king of rulers who tames the dangerous enemies, the [one] crowned with glory, the [one] unafraid of battle, the relentless lion, who shakes resistance, the king of praise, the shepherd, protection of the world, the king whose command blots out mountains and seas…

Translation from Samuel M. Paley, The King of the World: Ashur-nasir- pal IIof Assyria 883–859 B.C. [New York: The Brooklyn Museum, 1976]

The Neo-Assyrians feature prominently in the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible as the avengers of a straying Israel. In 722 BCE the Assyrians did finally conquer the kingdom of Israel. From its expansion in the ninth century BCE to its defeat by the Babylonians and the Medes, Neo-Assyria was one of many opulent cultures that flourished in that part of the world in the ancient world.

Think about buildings that communicate power in your communities. How are they decorated? What types of power do they convey? Share your thoughts with us and explore the palace of Ashur-nasir-pal and the arts of the ancient Assyrians II in our online collection.

Assyrian. Apkallu-figure and King Ashur-nasir-pal II, ca. 883-859 B.C.E. Alabaster. Brooklyn Museum, Purchased with funds given by Hagop Kevorkian and the Kevorkian Foundation, 55.155. Creative Commons-BY

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EXALTATION OF THE HOLY CROSS

September 14 - Today is the feast day of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

Today’s feast is a triumphant liturgy— a day in which red is worn to symbolize the glorious and saving sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross. The Church sings of the triumph of the Cross—no longer an instrument of death and torture—but the powerful and glorious instrument of our redemption. To follow Christ we must take up His cross, follow Him and become obedient until death, even if it means death on the cross. We identify with Christ on the Cross and become co-redeemers, sharing in His cross.

The Cross could not be decently mentioned amongst Romans, who looked upon it as an unlucky omen, and as Cicero says, not to be named by a freeman. However, the Emperor Constantine attributed his victory in the Quintian fields, near the bridge Milvius, to the Cross of the Christians, the inscription of which he caused to be put under his statue with which the senate honoured him in Rome, as Eusebius testifies. The same historian mentions that in his triumph, he did not mount the capitol, to offer sacrifices and gifts to the false gods, according to the custom of his predecessors, but “by illustrious inscriptions promulgated the power of Christ’s saving sign.”

EXHALTATION OF THE HOLY CROSS.

Adapted from The Liturgical Year by Abbot Gueranger

“Through Thee the precious Cross is honored and worshiped throughout the world.” Thus did Saint Cyril of Alexandria praise Our Lady on the morrow of that great day, which saw Her Divine Maternity vindicated at Ephesus. Eternal Wisdom has willed that the Octave of Mary's Birth should be honored by the celebration of this Feast of the triumph of the Holy Cross. The Cross indeed is the standard of God's armies, whereof Mary is the Queen; it is by the Cross that She crushes the serpent's head, and wins so many victories over error, and over the enemies of the Christian name.

“By this sign thou shalt conquer.” Satan had been suffered to try his strength against the Church by persecution and tortures; but his time was drawing to an end. By the edict of Sardica, which emancipated the Christians, Galerius, when about to die, acknowledged the powerlessness of Hell. Now was the time for Christ to take the offensive, and for His Cross to prevail. Towards the close of the year 311, a Roman army lay at the foot of the Alps, preparing to pass from Gaul into Italy. Constantine, its commander, together with his soldiers, already belonged henceforward to the Lord of hosts. The Son of the Most High, having become the Son of Mary, King of this world, was about to reveal Himself to His first lieutenant, and, at the same time, to discover to His first army the standard that was to go before it. Above the legions, in a cloudless sky, the Cross, proscribed for three long centuries, suddenly shone forth; all eyes beheld it, making the western sun, as it were, its footstool, and surrounded with these words in characters of fire: IN HOC VINCE: By this sign conquer! A few months later, October 27, 312, all the idols of Rome stood aghast to behold, approaching along the Flaminian Way, beyond the bridge Milvius, the Labarum with its sacred monogram, now become the standard of the imperial armies. On the morrow was fought the decisive battle, which opened the gates of the eternal City to Christ, the only God, the everlasting King.

“O great and admirable mystery!” cries out Saint Augustine. “He must increase, but I must decrease, said John, said the voice which personified all the voices that had gone before announcing the Father's Word Incarnate in His Christ. Every word, in that it signifies something, in that it is an idea, an internal word, is independent of the number of syllables, of the various letters and sounds; it remains unchangeable in the heart that conceives it, however numerous may be the words that give it outward existence, the voices that utter it, the languages, Greek, Latin and the rest, into which it may be translated. To him who knows the word, expressions and voices are useless. The prophets were voices, the Apostles were voices; voices are in the psalms, voices in the Gospel. But let the Word come, the Word Who was in the beginning, the Word Who was with God, the Word Who was God; when we shall see Him as He is, shall we hear the Gospel repeated? Shall we listen to the prophets? Shall we read the Epistles of the Apostles? The voice fails where the Word increases… Not that in Himself the Word can either diminish or increase. But He is said to grow in us, when we grow in Him. To him, then, who draws near to Christ, to him who makes progress in the contemplation of wisdom, words are of little use; of necessity they tend to fail altogether. Thus the ministry of the voice falls short in proportion as the soul progresses towards the Word; it is thus that Christ must increase and John decrease. The same is indicated by the beheading of John, and the exaltation of Christ upon the Cross; as it had already been shown by their birthdays: for, from the birth of John the days begin to shorten, and from the birth of Our Lord they begin to grow longer.”

“Hail, O Cross, formidable to all enemies, bulwark of the Church, strength of princes; hail in thy triumph! The sacred Wood still lay hidden in the earth, yet it appeared in the heavens announcing victory; and an emperor, become Christian, raised it up from the bowels of the earth.” Thus sang the Greek Church yesterday, in preparation for the joys of today; for the East, which has not our Feast of May 3, celebrates on this one solemnity both the overthrow of idolatry by the sign of salvation revealed to Constantine and his army, and the discovery of the Holy Cross a few years later in the cistern of Golgotha.

But another celebration, the memory of which is fixed by the Menology on September 13, was added in the year 335 to the happy recollections of this day; namely the Dedication of the Basilicas raised by Constantine on Mount Calvary and over the Holy Sepulcher, after the precious discoveries made by his mother, Saint Helena. In the very same century that witnessed all these events, a pious pilgrim, thought to be Saint Silva, sister of Rufinus the minister of Theodosius and Arcadius, attested that the anniversary of this Dedication was celebrated with the same solemnity as Easter and the Epiphany. There was an immense concourse of bishops, clerics, monks, and laity of both sexes, from every province; and the reason, she says, is that the “Cross was found on this day”; which motive had led to the choice of the same day for the first consecration, so that the two joys might be united into one.

Saint Sophronius, the holy Patriarch of Jerusalem, proclaimed: “It is the Feast of the Cross; who would not exult? It is the triumph of the Resurrection; who would not be full of joy? Formerly, the Cross led to the Resurrection; now it is the Resurrection that introduces us to the Cross. Resurrection and Cross: trophies of our salvation!” And the Pontiff then developed the instructions resulting from this connection.

It appears to have been about the same time that the West also began to unite in a certain manner these two great mysteries; leaving to September 14 the other memories of the Holy Cross, the Latin churches introduced into Paschal Time a special Feast of the Finding of the Wood of Redemption. In compensation, the present solemnity acquired a new luster to its character of triumph by the contemporaneous events which form the principal subject of the historical lessons in the Roman liturgy.

A century earlier, Saint Benedict had appointed this day for the commencement of the period of penance knows as the monastic Lent, which continues till the opening of Lent proper, when the whole Christian army joins the ranks of the cloister in the campaign of fasting and abstinence. “The Cross,” says Saint Sophronius, “is brought before our minds; who will not crucify himself? The true worshiper of the sacred Wood is he who carries out his worship in his deeds.”

The following are the lessons we have already alluded to:

About the end of the reign of the Emperor Phocas, Chosroes king of the Persians invaded Egypt and Africa. He then took possession of Jerusalem; and after massacring there many thousand Christians, he carried away into Persia the Cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ, which Saint Helena had placed upon Mount Calvary. Phocas was succeeded in the Empire by Heraclius; who, after enduring many losses and misfortunes in the course of the war, sued for peace, but was unable to obtain it even upon disadvantageous terms, so elated was Chosroes by his victories. In this perilous situation he applied himself to prayer and fasting, and earnestly implored God's assistance. Then, admonished from Heaven, he raised an army, marched against the enemy, and defeated three of Chosroes' generals with their armies.

Subdued by these disasters, Chosroes took to flight; and, when about to cross the river Tigris, named his son Medarses his associate in the kingdom. But his eldest son Sisroes, bitterly resenting this insult, plotted the murder of his father and brother. He soon afterwards overtook them in flight, and put them to death. Sisroes then had himself recognized as king by Heraclius, on certain conditions, the first of which was to restore the Cross of Our Lord. Thus, 14 years after It had fallen into the hands of the Persians, the Cross was recovered; and on his return to Jerusalem, Heraclius, with great pomp, bore It back on his own shoulders to the Mount whither Our Savior had carried It.

This event was signalized by a remarkable miracle. Heraclius, attired as he was in robes adorned with gold and precious stones was forced to stand still at the gate which led to Mount Calvary. The more he endeavored to advance, the more he seemed fixed to the spot. Heraclius himself and all the people were as-tounded; but Zacharias, the Bishop of Jerusalem, said: Consider, O Emperor, how little thou imitatest the poverty and humility of Jesus Christ, by carrying the Cross clad in triumphal robes. Heraclius there-upon laid aside his magnificent apparel, and barefoot, clothed in poor attire, he easily completed the rest of the way, and replaced the Cross in the same place on Mount Calvary, whence It had been carried off by the Persians. From this event, the Feast of the Exultation of the Holy Cross, which was celebrated yearly on this day, gained fresh luster, in memory of the Cross being replaced by Heraclius on the spot where it had first been set up for Our Savior.

The victory thus chronicled in the sacred books of the Church was not the last triumph of the Holy Cross; nor were the Persians Its latest enemies. At the very time of the defeat of these fire-worshiping pagans, the prince of darkness was raising up a new standard—the crescent. By the permission of God, Islam also was about to try its strength against the Cross: a two-fold power, the sword and the seduction of the passions. But here again, in the secret combats between the soul and Satan, as well as in the great battles recorded in history, the final success was due to the weakness and folly of Calvary.

The Cross was the rallying-standard of all Europe in those sacred expeditions which borrowed from It their beautiful title of Crusades, and which exalted the Christian name in the East. While on the one hand the Cross was warding off degradation and ruin, on the other It was preparing the conquest of new continents; so that it was by the Cross that the West remained at the head of nations, rather than beneath the foot of the crescent. Through the Cross, the warriors in these glorious campaigns are inscribed on the first pages of the golden book of nobility. The orders of chivalry, which claimed to hold among their ranks the elite of the human race, looked upon the Cross as the highest mark of merit and honor.

O adorable Cross, our glory and our love here on earth, save us on the day when thou shalt appear in the heavens, when the Son of Man, seated in His majesty, is to judge the world!

THE EXALTATION OF THE HOLY CROSS

BY FATHER FRANCIS XAVIER WENINGER, 1876

This festival was instituted in commemoration of the day on which the holy Cross of Christ, was, with great solemnities, brought back to Jerusalem. Chosroes, king of Persia, had invaded Syria with a powerful army, and had conquered Jerusalem, the capital. He caused the massacre of eighty thousand men, and also took many prisoners away with him, among whom was the Patriarch Zachary. But more painful than all this to the Christians was, that he carried away the holy, Cross of our Saviour, which, after great pains, had been discovered by the holy empress, St. Helena. The pagan king carried it with him to Persia, adorned it magnificently with pearls and precious stones, and placed it upon the top of his royal throne of pure gold. Thus was the holy Cross held in higher honor by the heathen king, than Martin Luther would have manifested; for, in one of his sermons, he says of it: “If a piece of the holy Cross were given to me and I had it in my hand, I would soon put it where the sun would never shine on it.”

Heraclius, the pious emperor, was greatly distressed at this misfortune, and as he had not an army sufficiently large to meet so powerful an enemy, he made propositions for peace. Chosroes, inflated by many victories, refused at first to listen to the emperor's proposal, but at length consented, on condition that Heraclius should forsake the faith of Christ and worship the Sun, the god of the Persians. Indignant at so wicked a request, the emperor, seeing that it was a question of religion, concerning the honor of the Most High, broke off all negotiation with his impious enemy. Taking refuge in prayer, he assembled all the Christian soldiers of his dominions, and commanded all his subjects to appease the wrath of the Almighty, and ask for His assistance, by fasting, praying, giving alms and other good works. He himself gave them the example. After this, he went courageously, with his comparatively small army, to meet the haughty Chosroes, having given strict orders that his soldiers, besides abstaining from other vices, should avoid all plundering and blaspheming, that they might prove themselves worthy of the divine assistance.

Taking a crucifix in his hand, he animated his soldiers by pointing towards it, saying they should consider for whose honor they were fighting, and that there was nothing more glorious than to meet death for the honor of God and His holy religion. Thus strengthened, the Christian army marched against the enemy. Three times were they attacked by three divisions of the Persian army, each one led by an experienced general; and three times they repulsed the enemy, so that Chosroes himself had at last to flee. His eldest son, Siroes, whom he had excluded from the succession to the throne, seized the opportunity, and not only assassinated his own father, but also his brother, Medarses, who had been chosen by Chosroes as his associate and successor. To secure the crown which he had thus forcibly seized, Siroes offered peace to Heraclius, restored to him the conquered provinces, and also sent back the holy Cross, the patriarch Zachary, and all the other prisoners of war. Heraclius, in great joy, hastened with the priceless wood to Jerusalem, to offer due thanks to the Almighty for the victory, and to restore the holy Cross, which the Persians had kept in their possession during fourteen years, to its former place.

All the inhabitants of the city, the clergy and laity, came to meet the pious emperor. The latter had resolved to carry the Cross to Mount Calvary, to the church fitted up for its reception. A solemn procession was formed, in which the Patriarch, the courtiers and an immense multitude of people took part. The clergy preceded, and the emperor, arrayed in sumptuous robes of state, carried the holy Cross upon his shoulder. Having thus passed through the city, they came to the gate that leads to Calvary, when suddenly the emperor stood still and could not move from the spot. At this miracle, all became frightened, not knowing what to think of it. Only to St. Zachary did God reveal the truth. Turning to the emperor the patriarch said: “Christ was not arrayed in splendor when He bore His Cross through this gate. His brow was not adorned with a golden crown, but with one made of thorns. Perhaps, O emperor, your magnificent robe is the cause of your detention.”

The pious Heraclius humbly gave ear to the words of the patriarch, divested himself of his imperial purple, and put on poor apparel, he took the crown from his head and the shoes from his feet. Having done this, the sacred treasure was again laid on his shoulder: when, behold! nothing detained him, and he carried it to the place of its destination. The holy patriarch then deposited the Cross in its former place, and duly venerated it with all who were present. God manifested how much He was pleased with the honor they had paid to the holy Cross of Christ, by many miracles wrought on the same day. A dead man was restored to life by being touched by the sacred wood; four paralytic persons obtained the use of their limbs; fifteen who were blind received sight; many sick recovered their health; and several possessed were freed from the devil by devoutly touching it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Categorizing and POS Tagging with NLTK Python

Categorizing and POS Tagging with NLTK Python

Natural language processing is a sub-area of computer science, information engineering, and artificial intelligence concerned with the interactions between computers and human (native) languages. This is nothing but how to program computers to process and analyze large amounts of natural language data.

NLP = Computer Science + AI + Computational Linguistics

In another way, Natural language processing is the capability of computer software to understand human language as it is spoken. NLP is one of the component of artificial intelligence (AI).

About NLTK :

The Natural Language Toolkit, or more commonly NLTK, is a suite of libraries and programs for symbolic and statistical natural language processing (NLP) for English written in the Python programming language.

It was developed by Steven Bird and Edward Loper in the Department of Computer and Information Science at the University of Pennsylvania.

A software package for manipulating linguistic data and performing NLP tasks.

NLTK is intended to support research and teaching in NLP or closely related areas, including empirical linguistics, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, information retrieval, and machine learning

NLTK supports classification, tokenization, stemming, tagging, parsing, and semantic reasoning functionalities.

NLTK includes more than 50 corpora and lexical sources such as the Penn Treebank Corpus, Open Multilingual Wordnet, Problem Report Corpus, and Lin’s Dependency Thesaurus.

The process of classifying words into their parts of speech and labelling them accordingly is known as part-of-speech tagging, POS-tagging, or simply tagging. Parts of speech are also known as word classes or lexical categories. The collection of tags used for a particular task is known as a tag set.

Using a Tagger

A part-of-speech tagger, or POS-tagger, processes a sequence of words, and attaches a part of speech tag to each word. To do this first we have to use tokenization concept (Tokenization is the process by dividing the quantity of text into smaller parts called tokens.)

>>> import nltk >>>from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize >>> text = word_tokenize("Hello welcome to the world of to learn Categorizing and POS Tagging with NLTK and Python") >>> nltk.pos_tag(text)

OUTPUT:

[('Hello', 'NNP'), ('welcome', 'NN'), ('to', 'TO'), ('the', 'DT'), ('world', 'NN'), ('of', 'IN'), ('to', 'TO'), ('learn', 'VB'), ('Categorizing', 'NNP'), ('and', 'CC'), ('POS', 'NNP'), ('Tagging', 'NNP'), ('with', 'IN'), ('NLTK', 'NNP'), ('and', 'CC'), ('Python', 'NNP')]

In the above output and is CC, a coordinating conjunction;

Learn is VB, or verbs;

for is IN, a preposition;

NLTK provides documentation for each tag, which can be queried using the tag,

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘RB’)

RB: adverb

occasionally unabatingly maddeningly adventurously professedly

stirringly prominently technologically magisterially predominately

swiftly fiscally pitilessly …

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘RB’)

RB: adverb

occasionally unabatingly maddeningly adventurously professedly

stirringly prominently technologically magisterially predominately

swiftly fiscally pitilessly …

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘NN’)

NN: noun, common, singular or mass

common-carrier cabbage knuckle-duster Casino afghan shed thermostat

investment slide humour falloff slick wind hyena override subhumanity

machinist …

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘NNP’)

NNP: noun, proper, singular

Motown Venneboerger Czestochwa Ranzer Conchita Trumplane Christos

Oceanside Escobar Kreisler Sawyer Cougar Yvette Ervin ODI Darryl CTCA

Shannon A.K.C. Meltex Liverpool …

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘CC’)

CC: conjunction, coordinating

& ‘n and both but either et for less minus neither nor or plus so

therefore times v. versus vs. whether yet

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘DT’)

DT: determiner

all an another any both del each either every half la many much nary

neither no some such that the them these this those

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘TO’)

TO: “to” as preposition or infinitive marker

to

>>> nltk.help.upenn_tagset(‘VB’)

VB: verb, base form

ask assemble assess assign assume atone attention avoid bake balkanize

bank begin behold believe bend benefit bevel beware bless boil bomb

boost brace break bring broil brush build …

The POS tagger in the NLTK library outputs specific tags for certain words. The list of POS tags is as follows, with examples of what each POS stands for.

CC coordinating conjunction

CD cardinal digit

DT determiner

EX existential there (like: “there is” … think of it like “there exists”)

FW foreign word

IN preposition/subordinating conjunction

JJ adjective ‘big’

JJR adjective, comparative ‘bigger’

JJS adjective, superlative ‘biggest’

LS list marker 1)

MD modal could, will

NN noun, singular ‘desk’

NNS noun plural ‘desks’

NNP proper noun, singular ‘Harrison’

NNPS proper noun, plural ‘Americans’

PDT predeterminer ‘all the kids’

POS possessive ending parent’s

PRP personal pronoun I, he, she

PRP$ possessive pronoun my, his, hers

RB adverb very, silently,

RBR adverb, comparative better

RBS adverb, superlative best

RP particle give up

TO, to go ‘to’ the store.

UH interjection, errrrrrrrm

VB verb, base form take

VBD verb, past tense took

VBG verb, gerund/present participle taking

VBN verb, past participle taken

VBP verb, sing. present, non-3d take

VBZ verb, 3rd person sing. present takes

WDT wh-determiner which

WP wh-pronoun who, what

WP$ possessive wh-pronoun whose

WRB wh-abverb where, when

Tagged Corpora

Representing Tagged Tokens

A tagged token is represented using a tuple consisting of the token and the tag. We can create one of these special tuples from the standard string representation of a tagged token, using the function str2tuple():

>>> tagged_token = nltk.tag.str2tuple('Learn/VB') >>> tagged_token ('Learn', 'VB') >>> tagged_token[0] 'Learn' >>> tagged_token[1] 'VB'

Reading Tagged Corpora

Several of the corpora included with NLTK have been tagged for their part-of-speech. Here’s an example of what you might see if you opened a file from the Brown Corpus with a text editor:

>>> nltk.corpus.brown.tagged_words() [('The', 'AT'), ('Fulton', 'NP-TL'), ...] >>> nltk.corpus.brown.tagged_words(tagset='universal') [('The', 'DET'), ('Fulton', 'NOUN'), ...] >>> [('The', 'DET'), ('Fulton', 'NOUN'), ...]

Part of Speech Tag set

Tagged corpora use many different conventions for tagging words.

TagMeaningEnglish Examples

ADJadjectivenew, good, high, special, big, local

ADPadpositionon, of, at, with, by, into, under

ADVadverbreally, already, still, early, now

CONJconjunctionand, or, but, if, while, although

DETdeterminer, articlethe, a, some, most, every, no, which

NOUNnounyear, home, costs, time, Africa

NUMnumeraltwenty-four, fourth, 1991, 14:24

PRTparticleat, on, out, over per, that, up, with

PRONpronounhe, their, her, its, my, I, us

VERBverbis, say, told, given, playing, would

.punctuation marks. , ; !

Xotherersatz, esprit, dunno, gr8, univeristy

>>> from nltk.corpus import brown >>> brown_news_tagged = brown.tagged_words(categories='adventure', tagset='universal') >>> tag_fd = nltk.FreqDist(tag for (word, tag) in brown_news_tagged) >>> tag_fd.most_common()

Output

[('NOUN', 13354), ('VERB', 12274), ('.', 10929), ('DET', 8155), ('ADP', 7069), ('PRON', 5205), ('ADV', 3879), ('ADJ', 3364), ('PRT', 2436), ('CONJ', 2173), ('NUM', 466), ('X', 38)]

Nouns

Nouns generally refer to people, places, things, or concepts, for example.: woman, Scotland, book, intelligence. The simplified noun tags are N for common nouns like book, and NP for proper nouns like Scotland.

>>> word_tag_pairs = nltk.bigrams(brown_news_tagged) >>> noun_preceders = [a[1] for (a, b) in word_tag_pairs if b[1] == 'NOUN'] >>> fdist = nltk.FreqDist(noun_preceders) >>> [tag for (tag, _) in fdist.most_common()] ['DET', 'ADJ', 'NOUN', 'ADP', '.', 'VERB', 'CONJ', 'NUM', 'ADV', 'PRON', 'PRT', 'X']

Verbs

Looking for verbs in the news text and sorting by frequency

SOURCE:https://www.learntek.org/blog/categorizing-pos-tagging-nltk-python/

>>> wsj = nltk.corpus.treebank.tagged_words(tagset='universal') >>> brown_news_tagged = brown.tagged_words(categories='adventure', tagset='universal') >>> wsj = nltk.corpus.treebank.tagged_words(tagset='universal') >>> [wt[0] for (wt, _) in word_tag_fd.most_common(200) if wt[1] == 'VERB'] ['is', 'said', 'was', 'are', 'be', 'has', 'have', 'will', 'says', 'would', 'were', 'had', 'been', 'could', "'s", 'can', 'do', 'say', 'make', 'may', 'did', 'rose', 'made', 'does', 'expected', 'buy', 'take', 'get']

0 notes

Text

Thoth - Lord of the Holy Words

Thoth [E=Tahuti]

The most popular and enduring of all the gods, Thoth has been responsible for keeping Egyptian magic in the forefront of learning since the collapse of the empire. Although in the later Dynastic period he was merely labelled the 'scribe of the gods'.

The magician's magician since he is endowed with complete knowledge and wisdom. He invented all the arts and sciences, astronomy, soothsaying, magic, medicine, surgery and most important of all - writing. As inventor of hieroglyphs, he was titled 'Lord of the Holy Words'; he was the first of magicians and compiled books of magic which contained 'formulas which commanded all the forces of nature and subdued the very gods themselves'. He appears to be long-suffering and is usually called upon to sort out the chaos created by the rest of the pantheon.

It was this power that earned him the name Tahuti - three times very, very great - which the Greeks translated as Hermes Trismegistus. He is identified as a lunar deity [E=Aah-tehuti] and his sacred animals are the ibis and the baboon. His chief festival was celebrated on the 'nineteenth of the month of Thoth', a few days after the full moon at the beginning of the Egyptian New Year. He was later identified with Mercury but should never be under-estimated, especially his role within the Primitive Path. He is associated with Hod on the Tree of Life and The Magus in the Tarot, his colour being amethyst the symbol of mystical power.

Day 19 of Dhwty in the season of Aket (Inundation)

(6th August, depending on how calendar is calculated)

Feast of Thoth.

A happy day in heaven in front of Re, the Great Ennead is in great festivity. Burn incense on the fire. It is the day of receiving. It is the day of going forth of Thoth.

Prayer or divinatory time: dawn.

Prayer or Invocation

Such was all-knowing Tahuti [Thoth], who saw all things,

and seeing understood,

and understanding has the power to disclose

and to give explanation.

For what he knew, he graved on stone;

Yet though he graved them onto stone he hid them mostly...

The sacred symbols of the cosmic elements

he hid away hard by the secrets of Osms

... keeping sure silence,

that every younger age of cosmic time might seek for them.

(Kore Kosmu -G SR Meade translation]

I have just been reading The Wisdom of Ancient Egypt by Joseph Kaster (originally published in 1968), anyway the chapter I was making some notes on concerned the Pyramid Texts and the story of Osiris (I should add that it was a compilation of spells or groups of spells rearranged to tell the story). There was a section that dealt with the assigning of Osiris in his place in the genealogy of the Gods, and Thoth was listed as one of the brothers of Osiris. In a footnote it said that it was one of the few references to Thoth as a brother of Osiris and an accomplice of Set.

[Thoth aids Set against Osiris]

Behold what Set and Thoth have done, your two brothers, who knew not how to weep for you!

Set, this your brother is this one here, Osiris, who is made to endure and to live, that he may punish you!

Thoth, this your brother is this one here, Osiris, who is made to endure and to live, that he may punish you!

Goddesses linked with Thoth

There are several Goddesses linked with Thoth, most notably Isis, with the help of Thoth she is able to resurrect Osiris long enough for her to concieve Horus (the Yonger). Later when she is hiding in the Delta papyrus swamps, one of the seven scorpion helpers of Isis, either through malice or clumsiness stings Horus, in her grief she causes the sky barque of the sun god to stop, and refuses to let it go again until her son is cured. Once again Thoth comes to the rescue. It was Thoth who brought Tefnut, who left Egypt for Nubia in a sulk after an argument with her father, back to heaven to be reunited with Ra.

There is also Seshat (Sashet, Sesheta), meaning 'female scribe', was seen as the goddess of writing, historical records, accounting and mathematics, measurement and architecture to the ancient Egyptians. She was depicted as a woman wearing a panther-skin dress (the garb of the funerary stm priests) and a headdress that was also her hieroglyph, which may represent either a stylised flower or seven pointed star on a standard that is beneath a set of down-turned horns. (The horns may have originally been a crescent, linking Seshat to the moon and hence to her spouse, the moon god of writing and knowledge, Thoth.)

He was associated by the Egyptians with speech, literature, arts, learning. He, too, was a measurer and recorder of time, as was Seshat. Believed to be the author of the spells in the Book of the Dead, he was a helper (and punisher) of the deceased as they try to enter the underworld. In this role, his wife was Ma'at, the personification of order, who was weighed against the heart of the dead to see if they followed ma'at during their life.

He could also be equated as the Logos (Word) of God in similar role that Jesus would later come to represent. He is also associated with magic and Heka, the magical powers of Thoth were so great, that the Egyptians had tales of a 'Book of Thoth', which would allow a person who read the sacred book to become the most powerful magician in the world. The Book which "the god of wisdom wrote with his own hand" was, though, a deadly book that brought nothing but pain and tragedy to those that read it, despite finding out about the "secrets of the gods themselves" and "all that is hidden in the stars". The book of Thoth is supposed to be hidden in the Hall of Records which Edgar Cayce thought was beneath the Sphinx.

Thoth as Creator

Thoth's centre of worshipped was at Khmunu (Hermopolis) in Upper Egypt, where he was the creator god, in Ibis form, who laid the World Egg. The sound of his song was thought to have created four frog gods and snake goddesses who continued Thoth's song, helping the sun journey across the sky.

Titles of Thoth

He was the 'One who Made Calculations Concerning the Heavens, the Stars and the Earth', the 'Reckoner of Times and of Seasons', the one who 'Measured out the Heavens and Planned the Earth'. He was 'He who Balances', the 'God of the Equilibrium' and 'Master of the Balance'. 'The Lord of the Divine Body', 'Scribe of the Company of the Gods', the 'Voice of Ra', the 'Author of Every Work on Every Branch of Knowledge, Both Human and Divine', he who understood 'all that is hidden under the heavenly vault'. Thoth was not just a scribe and friend to the gods, but central to order - ma'at - both in Egypt and in the Duat. He was 'He who Reckons the Heavens, the Counter of the Stars and the Measure of the Earth'.

www.thewhitegoddess.co.uk/the_gods/thoth_-_lord_of_the_holy_words.asp

0 notes

Photo

“And upon her forehead was a name written, mystery, babylon the great, the mother of harlots and abominations of the earth.” —the Apostle John

Have you ever seriously considered the origins of the world’s largest religion?

The Roman Catholic Church is the most recognizable and illustrious religion on Earth. Worldwide, it has more than 1.2 billion followers, roughly 400,000 priests and some 221,000 parishes. Catholicism has a presence on every continent and in every nation. Tens of millions of Catholics dutifully attend services each week. Around the world, Catholic priests and authorities are invited to contribute to conversations, public and private, on religion, politics, culture, morality and virtually every other subject.

More than 5 million tourists flock to Vatican City annually. They visit to admire Michelangelo’s legendary frescoes, to attend mass in the Sistine Chapel, and in the hope of catching a glimpse of the most venerated figure on the planet: the pope.

Yet despite its global ubiquity, colossal fame, material splendor and long history, the Catholic Church is an enigma. Even to lifelong Catholics.

Each summer more than 20,000 visitors—tourists presumably interested in Catholic history—walk through the Vatican’s museums every day. But if you stood outside these museums and asked people to explain the true origins of the Catholic religion, most couldn’t give a satisfactory answer. Even most devout Catholics are unable to provide a clear, convincing explanation of the identity of their religion. Most Catholic priests and historians will stumble when asked to reconcile what they believe about their religion and its doctrines with what the Bible teaches. Very few can clearly explain when Catholicism came into existence, where the religion began, who its earliest forefathers were, or the origins of its major practices.

The Catholic religion is the most famous Christian religion on Earth, yet it is shrouded in mystery.

Isn’t that remarkable? No institution, government or religion has shaped European history—which comprises a significant chunk of Western civilization—more than the Roman Catholic Church. As historian Thomas Woods wrote, “Western civilization owes far more to the Catholic Church than most people—Catholics included—often realize. The church, in fact, built Western civilization” (How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization).

It is inaccurate to imply that the Catholic Church is solely responsible for building Western civilization. The influence of English-speaking civilization, which had a distinct anti-popish, anti-Catholic identity, is responsible as much as if not more than the Catholic Church. But Woods’s fundamental point is correct. Catholic leadership and teaching has had a decisive and far-reaching influence on Western religion, politics, culture, science and education, often in ways most people fail to recognize.

The Vatican has presided over the rise and fall of kings and governments, the emergence of political and ideological movements, and the discovery and colonization of new lands and peoples. The Catholic religion has influenced every facet of Western society, from art and music to science to the measurement of time to the annual holidays we celebrate. Its influence over Europe is even more extensive: It has shaped Europe’s legal systems, its educational institutions, many of its most prominent cities, its economies and even agriculture.

When it comes to religion, every Christian denomination—except one—can directly or indirectly trace its lineage back to Roman Catholicism.

The Roman Catholic Church is the most defining and influential institution in Europe’s history—yet somehow it remains a total mystery!

This chapter provides a thorough, logical explanation of the origins of the Catholic Church. Unlike most works on this subject, the Bible forms the foundation of this study. After all, the Catholic Church invokes the authority of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus Christ and the apostles to support its claim that it is God’s true Church. Isn’t it reasonable, then, to ask what the Bible says about the origin of this church?

‘Mystery, Babylon the Great’

We have seen how a church is pictured symbolically in Revelation 17 as a woman. In verse 4, God prophesies that this woman, or church, would have an international presence, and would come to possess incredible wealth: “And the woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet colour, and decked with gold and precious stones and pearls ….” She would be unmistakable among the world’s religions. Her wealth and influence would be unmatched; she would truly be a religion to behold.

John also prophesies that this “woman” influences the “kings of the earth.” She has a habit of forming relationships with and ruling over secular governments. Verse 2 says the “inhabitants of the earth have been made drunk with the wine of her fornication.” She is an imperialistic religion with a habit of intertwining herself with secular governments. If you study history, only one church can consistently be described this way.

Verse 9 says this church sits atop “seven mountains.” Only one city on Earth is famously situated on “seven hills” and is home to the headquarters of a colossal religion. Verse 18 says, “And the woman which thou sawest is that great city, which reigneth over the kings of the earth.”

Only one city has historically fulfilled this criteria: Rome.

Many Bible scholars and historians agree on the identity of the woman of Revelation 17.

Matthew Henry’s commentary says, “Rome clearly appears to be meant in this chapter. Pagan Rome subdued and ruled with military power, not by art and flatteries. … [I]t is well known that by crafty and political management, with all kinds of deceit of unrighteousness, papal Rome has obtained and kept her rule over kings and nations.”

Clarke’s Commentary explains, “Therefore the 10 horns must constitute the principal strength of the Latin empire; that is to say, this empire is to be composed of the dominions of 10 monarchs independent of each other in every other sense except in their implicit obedience to the Latin [or Roman] church” (emphasis added throughout).

The Scofield Bible says, “Two ‘Babylons’ are to be distinguished in the Revelation: ecclesiastical Babylon, which is apostate Christendom, headed up under the papacy; and political Babylon, which is the beast’s confederated empire, the last form of Gentile world-dominion.”

Some will find it hard to accept that the woman in Revelation 17 is the Roman Catholic Church. But it wasn’t all that long ago that this truth was widely accepted, even by biblical scholars—some of whom were Catholic.

The Apostle John wrote the book of Revelation in the first century, long before the term Catholic, which means universal, came into existence. If we are to discover the origins of the Catholic Church in the Bible, we cannot search for the term Catholic. We must search for it using the name given to it by God. What does God call the “woman” of Revelation 17? Verse 5 reveals the answer—and, emblazoned on her forehead, it couldn’t be more explicit:

“And upon her forehead was a name written, Mystery, Babylon the Great ….” (Isn’t it interesting that John, as early as the first century, prophesied that this religion would be a mystery? “Mystery” is part of this woman’s name!)

Consider the biblical name of the church discussed in Revelation 17: Babylon the Great. Babylon literally means confusion, which is an apt description of this religion and its doctrines. The term Babylon also refers to the city of ancient Babylon. God inspired the use of this term to describe the world-dominating religion discussed in Revelation 17 for a reason: The Catholic Church, including many of its teachings, traces its heritage all the way back to ancient Babylon.

That is where we must now visit.

Ancient Babylon

Genesis 8:4 says that after the rains of the great Flood stopped and the waters receded, the ark in which Noah and his family resided “came to rest on the mountains of Ararat” (English Standard Version). These mountains are located in eastern Turkey. Following the Flood, Noah and his growing family—the seed of post-Flood humanity—migrated eastward into the “land of Shinar,” which means the “country of the two rivers,” referring to the Tigris and the Euphrates. Shinar is another name for the region of Babylonia.

The epicenter of post-Flood human civilization was the region of Babylon, the capital of which was the city of Babylon, which sits beside the Euphrates River. It is to this city that nearly all of this world’s nations—and religions (with one exception)—can trace their earliest beginnings. For more information about this ancient civilization, request a free copy of Herbert W. Armstrong’s book Mystery of the Ages.

The history of ancient Babylon is covered in Genesis 10 and 11. The Bible doesn’t furnish many details, but those it does give are profound and enlightening. Many individuals are listed in these chapters, but one man in particular is given a comparatively detailed biography. He is described as having a “mighty” influence over ancient Babylonian civilization. He was the king of Babylon. His name was Nimrod, which in Hebrew means rebellious and lawless.

Nimrod was the son of Cush, and thus a great-grandson of Noah. Genesis 10:8 says Nimrod emerged as a powerful leader in his day and that he “began to be a mighty one in the earth.” Biblical record shows that Nimrod promised people protection from dangerous wild animals. This protection mostly came in the form of walled cities, the first of which was Babylon. It didn’t take Nimrod long to establish total control over the people. Ensconced within his city, and dependent on him for survival, the people effectively belonged to Nimrod.

Thus Babylon, the capital of Mesopotamia and seat of human civilization, came to reflect Nimrod’s character and ambition—morally, politically and religiously.

What was Nimrod’s character? The words “mighty one” in Genesis 10:8 are translated from a Hebrew word that connotes a tyrant. Verse 9 records that he was a “mighty hunter before the Lord”; the Hebrew word translated before should more accurately be translated as against. Nimrod was a tyrant whose primary motivation in life was working against God. Nimrod constructed the city of Babylon and established the entire Babylonian kingdom—which included most of the world’s population at the time—in an act of rebellion against God!

Nimrod set himself up as the supreme, infallible religious authority. He put himself before God. To his followers, Nimrod was God!

This explains why, in the Bible, Babylon is generally synonymous with rebellion and lawlessness.

Genesis 11 records Nimrod’s construction of the city of Babylon. His motive for building this city is noteworthy. Verse 4 records that it was an attempt to “make us a name”—to gain eminence and renown. Neither God nor His servant Noah had authorized Babylon’s construction. Moreover, the fact that the people constructed a tower “whose top may reach unto heaven” shows that the people knew they were disobeying God. Nimrod and his rebellious followers remembered the Flood—which was punishment for mankind’s rebellion—and were building a gigantic tower to try to escape another flood that might come as a result of their wickedness.

Babylon’s construction represented an attempt by Nimrod and the people to separate themselves from God—and to counterfeit the work God was performing through Noah.

Babylon was the headquarters of Nimrod’s campaign to oppose God. As Herbert W. Armstrong wrote, it was Nimrod who “started the great organized worldly apostasy from God that has dominated this world until now” (The Plain Truth About Christmas). Together with his wife, Semiramis (who was also his mother), Nimrod concocted, then imposed on his followers, his own system of finance, politics and education.

Nimrod exalted himself as the religious leader of the people. He established himself as the chief spiritual authority in place of God and God’s servant Noah. As the priest of Babylon, and in league with Semiramis, Nimrod conceived the Babylonian mystery religion, which included a multitude of pagan religious doctrines and practices. Today many of the practices and symbols associated with Christmas and Easter, for example, can be traced back to ancient Babylon. (For proof, read Alexander Hislop’s book The Two Babylons, available in bookstores.)

Nimrod was eventually killed by Noah’s son Shem. But the false and rebellious political and religious system he created did not die with him. It thrived, thanks to the work of Semiramis. With her son dead, as Hislop explains, Semiramis convinced her followers that Nimrod now lived as an immortal spirit being. In death, Nimrod was worshiped as a god. He became known as the messiah. Together, Semiramis and Nimrod—the original mother and child duo—became chief objects of worship in ancient Babylon.

The doctrines of the immortal soul and mother-child worship—to name only two Catholic teachings—can be traced directly back to Nimrod and Babylon.

By the time he died, Nimrod’s false system was entrenched in mankind. One cannot overstate what Nimrod and Semiramis achieved in Babylon. It was from this rebellious civilization that all other civilizations emerged. The Bible clearly records the confusion of the languages and the dispersion of the various peoples from the region of Babylon (Genesis 11). As the various races and peoples dispersed, they took with them the beliefs and practices of the Babylonian mystery religion, many of which remained ingrained—though they were often altered—in the new religions developed by the various races.

“Semiramis was actually the founder of much of the world’s pagan religions, worshiping false gods,” Mr. Armstrong wrote in Mystery of the Ages. Many mainstream symbols and holidays, even Christian doctrines and practices, still in common use today can be traced back to the Babylonian mystery religion. Christmas and the Christmas tree, Easter, Sunday worship, the trinity, the “sacred” mother-child relationship—these beliefs and practices are all rooted in ancient Babylon.

The Bible is clear that the name Babylon is synonymous with Nimrod, his act of rebellion, and his post-Flood establishment of the Babylonian mystery religion. In Revelation 17:5, when God associates this “woman,” or church, with Nimrod and ancient Babylon, He is showing us that this religion is the offspring of the Babylonian mystery religion, a continuation of the pagan religious system created by Nimrod in blatant rebellion against God.

There are similarities in doctrines and practices between the Babylonian mystery religion and the Catholic religion. But this could be coincidence, unless there is something to directly connect ancient Babylon to the Roman Catholic Church.

That key piece of evidence exists and is, yet again, clearly revealed in the Bible.

Mystery Religion Relocates

The events described in 2 Kings 17 take place about 720 years before the time of Christ. By the eighth century b.c. the nation of Israel had split in two. The 10-tribed kingdom of Israel existed in Samaria, a region north of Jerusalem that encompasses parts of modern Lebanon and Syria. The kingdom of Judah existed in the south with Jerusalem as its capital.

2 Kings 17 recalls God’s punishment on the 10-tribed nation of Israel for rejecting His law. “For so it was, that the children of Israel had sinned against the Lord their God,” verse 7 says. Under the leadership of the Ephraimite king, Jeroboam, Israel was embracing pagan gods, erecting heathen statues, and disobeying God’s command to keep the Sabbath. God had warned them extensively through a series of prophets. But the people remained staunch in their rebellion.

In the late eighth century b.c., God punished the Israelites by having the Assyrians, a cruel and war-loving people from the region of Mesopotamia, invade Samaria. “Then the king of Assyria came up throughout all the land, and went up to Samaria, and besieged it three years” (verse 5). This besiegement and invasion occurred between 721 and 718 b.c.

Now notice: “In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria …” (verse 6). The Israelites were picked up and relocated. (To learn where they went, request a copy of Herbert W. Armstrong’s book The United States and Britain in Prophecy, and we will send it to you at no cost.)

After the Assyrians removed the Israelites from their towns and cities, they did not leave Samaria uninhabited. The Bible records that “the king of Assyria brought men from Babylon, and from Cuthah [near Babylon] … and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel: and they possessed Samaria, and dwelt in the cities thereof” (verse 24).

This explains the perpetuation of Nimrod’s Babylonian mystery religion.

At this moment, around 718 b.c., tens of thousands of Babylonians, perhaps more—people steeped in the teachings and practices of Nimrod’s Babylonian mystery religion—were planted in the region of Samaria. The Babylonians and the false religion of Nimrod and Semiramis became entrenched there.