Text

Analytical Application 1

Culture industry:

The culture industry includes many facets of our society, such as popular media and entertainment. Horkheimer and Adorno theorize that the culture industry was created with consumers in mind, hence why it is accepted with little resistance.[1] They also mention how technology has become a huge driving force in the control of those with less power in society. “Technical rationality today is the rationality of domination.”[2] Without the power of technology, the culture industry has less dominance over society.

The Amazon Alexa advertisement is the epitome of the culture industry at large, especially as it goes to show that technology is now a large part of what keeps the culture industry going. Having celebrities, especially these celebrities whose names are brands, act as the voice behind the product is an incredibly accurate way of depicting the culture industry, however accidental it may have been. Horkheimer and Adorno also mention the way celebrities are put up on pedestals as idealized versions of regular people that keep the masses dreaming for stardom, which ultimately helps keep the culture industry going.[3] The usage of celebrities to voice Alexa in this ad plays into the idea that celebrities do normal, everyday things just like the rest of us, yet they have achieved this level of success and notoriety that makes them worthy of our attention and respect. The irony of Amazon being the company to use celebrities in order to make their brand seem more down to earth is incredibly blasphemous, especially considering its track record with the environment and labor. Using celebrities like this distracts the audience from these failings, providing viewers instead with hilarious skits featuring well-known celebrities in order to keep the company in good graces with the general public.

Ideological state apparatus:

Ideological state apparatuses are institutions and systems that express certain ideologies, molding and sculpting the minds of those that participate in them. Some examples include schools, churches, family and communications (media and the like). Althusser also notes that “the Ideological State Apparatuses function massively and predominantly by ideology, but they also function secondarily by repression, even if ultimately, but only ultimately, this is very attenuated and concealed, even symbolic.”[4]

The Zazoo condom ad addresses one facet of the ideological state apparatus (ISA): the family ISA. The family is where we learn about the values we should be holding in our society, and what sort of things we should be trying to achieve to be successful later in life. Our family shapes these ideals, one of which being the way we think about raising children. The advertisement shows a father unable to control his son in a grocery store, leading him to think that he should’ve worn a condom instead of having kids. This ad explicitly goes against the general ideas that the family ISA tries to parrot, that raising kids is the most important thing one can do in their life. Perhaps it is because the family ISA covers up all the not so ideal moments, such as the kid throwing a fit in the grocery store, that necessitates an alternative perspective in the form of this advertisement. The no-kids sentiment is growing among people of the younger generations, if not because of direct experiences with children that make them want to put on a condom, then it is because of advertisements like this. The ISA, according to Althusser, often tries to mold our perception of the world into certain ideologies. With this advertisement, Zazoo creates a new kind of ideology previously untouched by the family ISA, that of not raising children—specifically because they’re annoying to work with at times.

Mechanical reproduction:

Mechanical reproduction describes the reproduction of art with technological advancements, such as the printing press to reproduce writing. Benjamin writes of mechanical reproduction, “The situations into which the product of mechanical reproduction can be brought may not touch the actual work of art, yet the quality of its presence is always depreciated.”[5] Though reproduced art may help distribute it to a wider audience, Benjamin’s theory suggests that this reproduced art is “less art” than the original.

The Sainsbury ad addresses mechanical reproduction through its main character, who works at a toy factory and ends up using it to make toy copies of himself. The toy clones are meant to replace the man at work and other places so that he can spend time with his family during the holidays. In the fantasy land of this advertisement, the toys are an acceptable copy of the guy and he is able to be in multiple places at once. However, according to Benjamin’s theory, the copies are a shallow representation of the original, and would ultimately be unable to hold up to the standards of the originals. Should Benjamin have written this ad, it might’ve gone something like this: the man is struggling to do everything, makes clones, they try to do his work but ultimately fail because they can’t do what the original did. The ad attempts to show it greater audience that the mechanically reproduced products are, in fact, able to live up to the original. This shows how advertisements are the cog that keeps the industry going; without advertisements to quell the worries of the people, they might realize that the mass-produced copies are not living up to the standards of the one-of-a-kind original.

Negotiated code:

Negotiated code is a manner of interpreting media that happens underneath the dominant code, typically by those who do not fall under the hegemonic culture. Hall writes, “Decoding within the negotiated version contains a mixture of adaptive and oppositional elements: it acknowledges the legitimacy of the hegemonic definitions to make the grand significations (abstract), while, at a more restricted, situational (situated) level, it makes its own ground rules – it operates with exceptions to the rule.”[6] While readers of the negotiated code are still able to read the code of the dominant position, their ability to read a code that appears outside of that dominance is what gives them the ability to resist.

The Bertlitz ad is an interesting one because it is clearly designed to be as humorous as possible. The comedic timing is on point and doesn’t miss a beat, staying strong until the very end. However, part of what makes it funny is the audience it’s designed for. The general American audience is primed to find this the most funny because of the man’s accent when speaking English and the premise of the ad being life or death. Somehow, those stakes feel funnier because it is poking fun at a person who doesn’t speak English fluently. While a general audience might get a kick out of this ad, there is a large majority of the world that doesn’t speak English fluently or as their first language who likely feel more seen by the man in the ad than anything else. These folks would be participating in the “negotiated code” as put forward by Hall. Despite being able to read the hegemonic definitions, seeing the way that the ad lays out a reason for improving one’s English speaking ability, there is also another way these folks can read the ad, which is the way it makes fun of non-fluent English speakers in a way that insinuates they should be learning how to speak it better. This all ties back to the dominance of English on the global stage, where English is valued over almost every other language spoken and to speak it without an accent is a survival skill.

Ruling class:

The ruling class is generally defined as those with the most societal power and money. Marx and Engels also define the ruling class as those that control ideas. “It is self-evident that they do this in its whole range, hence among other things rule also as thinkers, as producers of ideas, and regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age: thus their ideas are the ruling ideas of the epoch.”[7]

The Snickers ad represents the ruling class in a very subtle way through the assumption that the raw strength and power of the Snickers guy is desirable. In this sense, the best attributes of the ruling class are those of the patriarchy: strength, resilience and fortitude in men. The Snickers guy whips up the soccer player into shape who was complaining about an injury—as soccer players tend to do. Here, the audience is being told that those who have power should look and act like the Snickers guy because the strength and resilience he has is what makes him a man, and that is desirable. If the Snickers guy represents the ruling class in shape and form, then he also represents the ruling class as far as their ideas go. He goes forth into the world to put out the ideas he has about masculinity specifically when he sees others not a part of the ruling class abiding by these ideas. The tank he drives crushing the other cars before he even gets to confront the soccer player is a true testament to the lengths the ruling class will go to in order to ensure their ideas are the ones that proliferate through society.

Bibliography:

Horkheimer, Max and Adorno, Theodor W.. The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. In Dialectic of Enlightenment edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noeri, 94-136. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2002.

Althusser, L. Ideology and ideological state apparatuses. In L. Althusser (Ed.), Lenin and philosophy and other essays. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971.

Marx K. and Engels F. (1970). Ruling class and ruling ideas. In Storey J (ed.) Cultural theory and popular culture: A Reader. 4th ed. Essex: Pearson, 2009.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by J. A. Underwood. Penguin Great Ideas. Harlow, England: Penguin Books, 1936.

Hall, S. W. Encoding/Decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies (pp. 63-87). London: Hutchinson, 1980.

[1] Horkheimer & Adorno, The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception

[2] Horkheimer & Adorno

[3] Horkheimer & Adorno

[4] Althusser, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses

[5] Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

[6] Hall, Encoding, Decoding

[7] Marx & Engels, The Ruling Class and the Ruling Ideas

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Final Assessment

Overview, Methodology, Thesis

The analysis of Watchmen S1:E6 and S1:E8 begins with an understanding of the texts that provide a theoretical framework for such analysis. The first text is Jacques Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I,” which theorizes that an infant can recognize itself in the mirror, proving that a sense of self is possible without the language to describe it.[1] This sense of “I” will also be the most authentic self, as language inherently dilutes the idea through inaccuracies in speech. The second text, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” is bell hook’s work synthesizing Mulvey’s ideas about the male gaze in cinema and viewing it through a Black female perspective. The oppositional gaze, as hooks describes, is choosing “not to identify with either the victim or the perpetrator;”[2] it is a way for Black women to view cinema in an active manner, refusing to be content with stereotyped and victimized representation. Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference” is the third text. This work discusses the way Western society separates us by our defining characteristics so that we can categorize ourselves by dominating groups and subordinating groups. Lorde suggests we must recognize our differences in order to overcome our joint struggles, and at the same time we must unlearn the programming inside ourselves as we go about changing the structures and systems around us.[3] Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” is the fourth text, which highlights the reasons for inaccurate and shallow representation of Black communities in popular culture, despite Black popular culture often being co-opted for the popular culture.[4]

The theories presented in these texts can be used to analyze how well Watchmen portrays the relationships between the Black men and women in S1:E6 and S1:E8. Before I discuss the applications of the theorists to the episodes, I will parse through the commonalities and differences between the ideas each theorist presents. In episode 8, “A God Walks into Abar,” Angela and Doctor Manhattan—in the body of her husband, Cal—get into an argument about free will and agency where Manhattan insinuates and proves that Angela acts in a predetermined way. Angela refuses to accept this reality, and their relationship begins its crumble to an inevitable end. On the other hand, episode 6, “This Extraordinary Being,” highlights the agency June acts upon in her relationship with William, standing firm in her beliefs as she effectively ends their marriage and takes their son with her to Tulsa. The inability to recognize and understand another’s differences results in a breakdown of the relationship, including the misplacement of trust and empathy, which is fundamentally different from the refusal to accept someone’s actions that have a negative impact on the lives of those around them.

Commonalities and Comparisons

The theorists presented discuss common elements in their works, especially concerning identity, awareness and difference. In Lorde’s work, she elaborates on the way Black lesbians find themselves caught between white women’s racism and Black women’s homophobia. She writes how she is “constantly being encouraged to pluck out some one aspect of [her]self and present this as the meaningful whole, eclipsing or denying the other parts of self.”[5] The desire for people to separate themselves based solely on one category of difference in this way is incredibly isolating and deprives them of connection with any other aspect of their identity. This is similar to hook’s statement on Black women’s inability to find themselves represented in cinema because they face objectification from the Black male gaze when there are Black people represented, or they face erasure by white women being upheld as the peak of femininity in film.[6] As a result, Black women are often forced to turn to independent cinema or other ways of looking at films in order to find positive representations, which is where we get the oppositional gaze. In both cases, differences are used to separate and isolate people from connecting with a group that comprises their identity, which forces these isolated groups to the outside of the canon of representation. Lorde covers this, mentioning how Black women often discredit or do not even recognize the contributions of Black lesbians to Black communities. Part of this discrediting comes from pure homophobia, as being mistaken for a lesbian is not an ideal accusation to face.[7] However, part of it is rooted in the patriarchy, with Black women being fearful that Black men won’t pay them attention.[8] This system works intentionally to keep groups that should be working together from standing in solidarity with each other. This can lead to even further divisions between and within marginalized communities, which doesn’t allow for people to work with each other and might lead to poor representations. Hall’s work expands on this idea, as he postulates that the popular culture that comes out of Black communities is somewhat shallow and inauthentic.[9] The popular culture is dominant, which means that culture coming out of marginalized communities is inevitably homogenized, commodified and stereotyped. Popular culture coming out of the Black community, Hall writes, may have drawn upon Black experiences in its creation, but he asks us to “note how, within the black repertoire, style—which mainstream cultural critics often believe to be the mere husk, the wrapping, the sugar-coating on the pill—has become itself the subject of what is going on.”[10] The shallow, inauthenticity should not be our primary focus; instead, we must continue to look for the lived experiences within these representations. Without going beyond the surface level representation, there could result in what Lacan might call an impure “I.” Within his work, Lacan mentions the “ideal I,” which involves the recognition of oneself as a whole being.[11] Where this comes into conversation with Hall is in Black popular culture; if the generalized and inauthentic representation of the Black community is the only representation out there, what becomes of the “I?” Is it always impure because the recognition, even with the purest intentions, is always of a hollow representation?

Differences and Disagreements

Some of the differences between the theorists emerge in how they discuss the structures and systems that dominate our society. In hook’s work, she draws on Friedberg’s idea of identification replicating the structures of power that created these delineations to pose the question: why is feminist film criticism, having claimed to understand the totality of the female identity, “remains aggressively silent on the subject of blackness and specifically representations of black womanhood?”[12] There should be no reason for such aggressive silence, as hooks puts it, but there is a prevalent phenomenon of the most privileged women being the ones receiving the benefits of the activism, typically rich, white women. This idea that mainstream feminism fails to include and advocate for all women is not a new one. Lorde discusses it while also pushing back against the category of Black women that hooks highlights. She writes that Black women often discount or discredit the contributions of Black lesbians because there is a fear that a) they will be accused of being a lesbian, and b) they will be seen as unworthy of support and attention from Black men.[13] Here, there is a clear difference in how those that fall under the identity of Black women find themselves marginalized; hooks acknowledges the exclusion from feminism while Lorde focuses on the divisions that occur between Black women of different sexualities. Lorde also focuses on the idea of ‘difference’ as a way for society to separate its people into different categories, with those in dominant groups having more mobility and power than those in the so-called subordinate groups. She writes, “It is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences, and to examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them and their effects upon human behavior and expectation.”[14] The way difference has been stigmatized and sensationalized is just one reason why we fail to recognize and come to an understanding about our differences. It is also our refusal to break the patterns laid out by the systems that keep us from connecting, systems that keep those at the top of the difference hierarchy—rich white men—in power. Hall expands on the idea of difference in our postmodern world. He specifically cites the postmodern’s “deep and ambivalent fascination with difference”[15] as a method of co-opting and synthesizing cultures of marginalized groups. As opposed to the inherent discriminatory tactics that the exclusion hooks and Lorde write about, Hall proposes that difference can be seen as a positive thing when it is beneficial for the popular culture. This then results in shallow and inauthentic representation, as Hall later discusses, because the experiences drawn upon are hiding under the surface of whatever representation Black people have in popular culture. Lacan’s idea that the mirror stage is somehow corrupted by the time language factors into our lives contrasts the idea that Hall has about Black popular culture. Though Lacan would have it that there is a stark difference between the inner “I” and the social “I,”[16] Hall concludes that there is, in fact, enough drawn from Black communities regarding Black popular culture that, despite how shallow it may seem, the authentic and lived experiences make it a product of the Black community—however commodified it may be.[17]

Theorists in Conversation about Watchmen

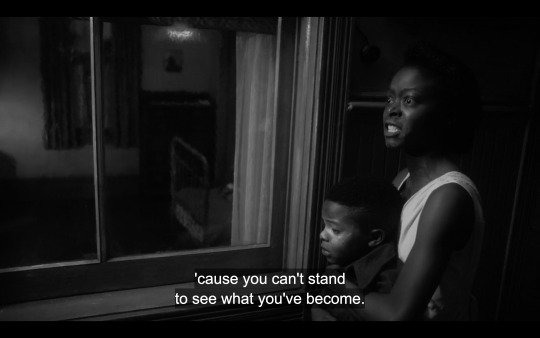

Both scenes from Watchmen that I will analyze consist of arguments between the couples in each episode. Episode 6, “This Extraordinary Being,” shows a righteously angry June protecting her son from his father, having been upset and wronged by his identity as a crime-fighting vigilante.

Episode 8, “A God Walks into Abar,” shows a righteously angry Angela defending her emotions from Doctor Manhattan’s reminders about his powers, having been upset and wronged by his identity as a time-transcending god.

Both scenes portray the way a Black woman advocates for herself in the relationship, refusing to allow her partner to direct her opinions and emotions. Both scenes also end with one member of the relationship leaving the room, simultaneously leaving their partner in shambles. Surprisingly enough, it is the scene set in the 1920s where the woman has more agency in the relationship; June rejects Will because of his commitment—or addiction—to fighting crime behind a mask and face paint, while in the more modern setting, Manhattan walks away from Angela because of her inability to understand his plight and his powers. The main difference is Angela’s inability to reconcile hers and Manhattan’s differences—how they experience time, for example—versus June’s refusal to accept how Will’s actions were becoming detrimental to their lives, including that of their son.

This Extraordinary Being

In “This Extraordinary Being,” the scene consists of what appears to be a long take—the cutting within the scene is primarily used to make it appear as though it is shot in one take. The unnoticeable cutting enhances the speed with which the scene moves along, making it so the camera can pan back and forth between Will and June. The panning motions gradually get slower as the scene goes on, with more lulls in conversation, lingering gazes and drawn out, emphatic lines from June.

The gradual slowing down of the pacing in the scene matches June’s dialogue and actions, showing that she is in control of the scene. When she enters, she interrupts Will wiping off the paint on his son’s face, simultaneously interrupting the instrumental in the soundtrack. When she leaves with her son, Will is forced to come to terms with his actions. If we position the Black woman as the subject of the gaze, hooks rejects Mulvey’s theory of visual pleasure, the ‘active/male’ and ‘passive/female,’ and “Placing ourselves outside that pleasure in looking, Mulvey argues, was determined by a ‘split between active/male and passive/female. Black female spectators actively chose not to identify with the film’s imaginary subject because such identification was disenabling.”[18] June exemplifies this by being the one to leave the relationship, refusing to be seen within the constraints of the male gaze. There is also a lot of emphasis placed on Will and June’s son, Marcus, and the implications his actions have in the scene.

His desire to copy his father is reminiscent of Lorde’s writing about our responses to difference: “Ignore it, and if that is not possible, copy it if we think it is dominant, or destroy it if we think it is subordinate.”[19] Seeing that his father paints his face white and dons a hood every night to fight crime, Marcus identifies that difference and tries to copy it, and this very act is what scares June into leaving Will. He has become so consumed by his alter identity as Hooded Justice that his image of self is unclear. June asks him “Which me?” because she doesn’t know which of his identities is the primal one.

Lacan theorizes that even with a successful dialectical synthesis of the primordial “I” and the discordant image in reality, there is still a difference between these two senses of self.[20] Because Will is unable to grapple with the two identities he balances his life with, his relationships suffer. June is unable to see him for the man she once knew, only seeing the way his vigilante identity has fed the anger that resides deep in his heart. Despite June’s self-advocacy generally being a good thing, her fear that Will’s anger will negatively impact her and her son is a product of what Hall names “aggressive resistance to difference”[21] that occurs during the opening up of society to accept difference. Perhaps it is a result of vigilante crime-fighters becoming more commonplace and less stigmatized that Though it could be that June’s resistance to Will is a result of vigilante crime-fighters becoming more commonplace and less stigmatized, she already resisted Will’s line of work—the police force, just the daytime version of his vigilante activities—because she knew he held onto all of his anger. It is important to consider that June’s resistance to difference comes from a place of understanding how her positionality as a Black woman affects how she moves through the world. Being someone that faces multiple kinds of marginalization, she may find that the best course of action when faced with someone who is filling her life with more hardship is to pack up and leave.

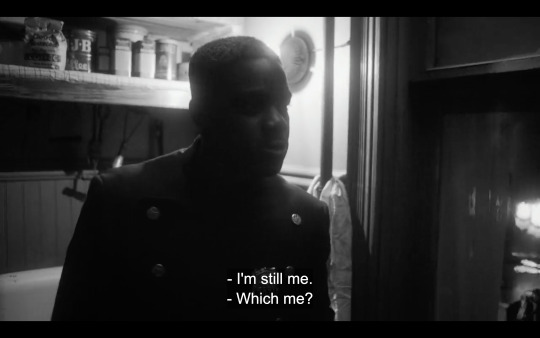

A God Walks into Abar

The scene from “A God Walks into Abar” flips the script and ends with Angela, the woman, being left rather than the other way around. It begins with the two characters having sex as Doctor Manhattan tells Angela about the night they met in the bar, except Manhattan is currently experiencing the moment; for Angela, that moment happened six months ago. Angela is upset when Manhattan tells her about the fight they will get into because she still doesn’t want to believe that it’s true. From here, the scene plays out as a conversation, with reaction shots for each character.

She rolls over in bed because she doesn’t want to hear this from him, the camera alternating depths of field so that only she is in focus. Even when the camera cuts to an angle on the other side of the bed, she is still in focus.

Her side of the story is getting more attention from the camera. However, Manhattan continues to push and push, telling Angela about the fight they’re going to have. It turns out that Angela denying that fight is what spurs it on. The camera no longer focuses its depth of field on Angela, now Manhattan is included in the picture.

This is literally and figuratively the camera taking focus away from Angela, the woman, in order to focus more on the man’s side of the story. This shift in focus is akin to the shift in power that occurs to ensure cultural hegemony. Hall writes, “It is always about shifting the balance of power in the relations of culture; it is always about changing the dispositions and the configurations of cultural power, not getting out of it.”[22] Though Angela is attempting to assert herself in the relationship, there is a shift in order to maintain cultural hegemony that keeps power away from her and more in the hands of Manhattan.

Both Angela and Manhattan sit up over the course of the argument’s progression, but when Angela sits up, the camera moves position to a low angle, whereas with Manhattan it stays at a neutral angle.

This implies the emotions each character has. From a low angle, Angela’s anger and distrust is apparent, but the neutral angle on Manhattan mirrors the sterilized attitude he approaches his nonlinear experience of time with. Lorde writes about the imbalance that occurs between those with different levels of marginalization. “Traditionally, in american society, it is the members of oppressed, objectified groups who are expected to stretch out and bridge the gap between the actualities of our lives and the consciousness of our oppressor.”[23] The difference in camera angles once the argument exemplifies the way Angela is forced to bear more of the communicative burden in the relationship; she has to do more of the heavy lifting. This puts such a strain on their relationship that eventually boils over at the end of their argument, resulting in Manhattan leaving Angela. His rigidity and unemotional manner of speaking about events he knows will come to pass is part of what angers her.

The first shot of Manhattan sitting up is a medium-close shot, but the next reaction shot on him is a close-up, indicating that his side of the story is becoming increasingly important and relevant.

Once they sit up—or stand, in Angela’s case—the over-the-shoulder shots are used more frequently. For the most part, these shots obey the 180-degree rule, which makes the cutting back and forth in the conversation easier to follow for the viewer. However, when Manhattan leans forward, the over-the-shoulder shot on him goes from his right to his left shoulder, allowing his back to take up a majority of the screen. This dominance over the screen also implies his dominance in the conversation, as well as his dominance over her. hooks writes, “In their role as spectators, black men could enter an imaginative space of phallocentric power that mediated racial negation,”[24] which perfectly exemplifies the dominance with which Manhattan is acting upon, leaving no room—literally and figuratively—for Angela’s perspective. In contrast, when there is a shot of Angela’s back turned towards Manhattan, it is done through a medium shot, and she barely takes up a third of the frame.

In the last shot of the scene—a medium shot on Angela—Manhattan gets up from the bed and leaves, out of focus in the background. Even though the story has come back to focus on her like it had at the beginning of the scene, she is not the one with agency.

When she advocates for herself, she is shut down, and ultimately is the one to be left, not doing the leaving. Lacan writes about the moment that the “I” goes from inner identification to synthesis with the outwardly perceived identity is the start of personal identities being “mediated by the other’s desire.”[25] In other words, our identity is shaped by those around us rather than coming from within. Angela is exerting this pressure upon Manhattan to conform to humanity since she is intimidated by his abilities, which has damaged their relationship since Manhattan can’t live up to her expectations. Ultimately, it is Angela and Manhattan’s inability to meet each other where they are, in a way that they can begin to understand how to live with each other’s differences that tears their relationship apart.

In Conclusion

To conclude this literature review and application, I would like to affirm that the fact that these two relationships are presented differently is inherently a good thing. If representation were to consist solely of one experience, it would become, as Hall writes, invisibility replaced by “regulated, segregated visibility.”[26] Marginalized groups being represented as a monolith in our popular culture is one of the biggest plagues in the fight for progress as we know it, for there can be no progress if we cannot understand and recognize our differences, as Lorde would have it. June and Angela having different experiences navigating their relationships as Black women is much needed in our media landscape. However, there is something to be said for the way each episode approaches the conflict each woman faces. June is forced to deal with a husband falling deeper and deeper into a workaholic obsession with his night job—fighting crime—to the point that it has begun to seep into every facet of his life. Both parents realize they have to draw the line when their son tries to emulate what his father does, June just so happens to have a drastically different idea of how to draw that line than Will does. Her taking control of the situation is emblematic of refusing to be victim or perpetrator, as hooks writes of the oppositional gaze. Angela, on the other hand, is dealing with someone so different from herself on such a grand scale that these differences are nearly impossible to understand. Though she does have a right to defend herself and stand firm in her beliefs, there is something to be said for her stark refusal to accept these differences between herself and Manhattan leading to her having less of a say in their relationship. Shutting off the connection between the two of them impedes both of their ability to come to an understanding of each other, as they will only be able to see each other for their differences, not as fully realized people. This is precisely the difference between the inner and the social "I" that Lacan writes about, the synthesis of which would lead to a fundamental understanding of each other. Ultimately, we are bettered by our understanding of each other’s differences, and we must strive to endeavor to hold our differences in high regard when moving through our society that so desperately wishes to tear us apart. Only when we are united, fighting against all our collective struggles, can we begin to build a society without a hierarchical system based on which identities are seen as valuable or dominant and which ones are not, where difference can simply exist as a defining characteristic of a human being.

Bibliography

Hall, Stuart. "Three What Is This “Black” in Black Popular Culture? [1992]" In Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora edited by David Morley, 83-94. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2018.

hooks, b. "Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators." In Feminist Film Theory. Edited by Sue Thornham. New York University Press: New York (2009).

Lacan, Jacques. 2006. The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Lorde, A. 1997. “Age Race Class and Sex : Women Redefining Difference.” Dangerous Liaisons S.

[1] Lacan, The Mirror Stage

[2] hooks, The Oppositional Gaze

[3] Lorde, Age, Race, Sex and Class

[4] Hall, What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?

[5] Lorde

[6] hooks

[7] Lorde

[8] Lorde

[9] Hall

[10] Hall

[11] Lacan

[12] hooks

[13] Lorde

[14] Lorde

[15] Hall

[16] Lacan

[17] Hall

[18] hooks

[19] Lorde

[20] Lacan

[21] Hall

[22] Hall

[23] Lorde

[24] hooks

[25] Lacan

[26] Hall

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Analytical Application 6

Dumbo: stereotype

Stereotype refers to actions taken by members of a marginalized group that are presented as representing the group as a whole. In general, stereotypes leave no room for nuanced depictions of members of these communities. Shohat and Stam sum this phenomenon up quite well: “within hegemonic discourse every subaltern performer/role is seen as synecdochically summing up a vast but putatively homogenous community.”[1]

In the clip from Dumbo, the crow characters emulate stereotypes of the Black community. Their voice actors—all of whom are white—speak in a way that both mimics and mocks the accent of Black Americans during the time period. One might even consider this act as the vocal version of blackface. A white person acting how they imagine a Black person may act is acting on a stereotype, and only furthers the stereotype by doing this acting. The song the crows sing is also an imitation of Black culture, drawing heavily on jazz and other music styles that came from the Black community in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Though attributing this music style to the Black community rather than repurposing and repackaging it may be seen as a positive thing, the cheap imitation of it only furthers the stereotype of the Black community. Especially when this imitation is presented by the dominant social and cultural group, there is no room for nuance, which Shohat and Stam say contributes to the stereotyping of marginalized communities. As a whole, this scene plays out as a stereotypical caricature with the aim to mock and portray Black Americans in an extremely negative light.

Lady and the Tramp: the Orient

The Orient in Western academia is always described from a perspective of Western colonial power. As Said illustrates in “Orientalism,” Europeans and Americans in the Orient are, in fact, Europeans or Americans first, individuals second.[2] The colonial power identity cannot be separated from the interest in the Orient. Said also points to the purposeful othering of the Orient and its people through the Western portrayal of the West as “familiar” and the Orient as “strange” or “mysterious.”[3]

Using Said’s definition of the Orient as a place that is mystified and othered, it is clear that the portrayal of the Siamese cats in Lady and the Tramp aims to mock and other Chinese people. The features on the cats like the slanted eyes and angular faces is reminiscent of caricatures of Chinese people in American political cartoons and advertisements, which were designed to other, isolate and promote racist ideas against Chinese immigrants and their families. The accent and word choice the cats use in the song also contribute to their othering; the voice actor uses a heavy Chinese accent and words in the song that mock the accents and word choices of native Chinese speakers speaking English. The traditional Chinese musical instruments used throughout the song also add to the othering and mystification of the Siamese cats as they stand out in the soundtrack from all the traditionally Western musical instruments. These factors culminate in a portrayal of characters that are stand ins for “Orientals,” who take on traits of the Orient that Said describes, making it so they are completely othered.

Peter Pan: essentialism

In Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture,” essentialism is described through the essentializing of difference. “It sees difference as ‘their traditions versus ours’, not in a positional way, but in a mutually exclusive, autonomous and self-sufficient one.”[4] Essentialism in this sense has the purpose of separation, of creating defined lines between certain groups and identities.

The scene from Peter Pan not only relies heavily on stereotypes of Native Americans, but also draws on essentialist ideas about marginalized cultures. Hall writes about essentialism as “their traditions versus ours,”[5] which is shown prominently in the scene through Wendy’s character. She is seen taking away the pipe from her younger brothers—a tradition she does not want them to participate in—and she is consistently put at odds with Tiger Lily, the daughter of the chief that Peter Pan rescued. Because Wendy is white, her ideas about tradition and culture are automatically favored by the viewer because they can see she is from the dominant culture, and it doesn’t help that the Native Americans are portrayed so unfavorably. Throughout the song, the singers accent and word choice are based on racist assumptions that Native Americans speak bad English or are uneducated. The character design of the Native Americans also portrays them as less than the Darlings and the other white characters. Other than their red skin tone—another racist stereotype—the characters are designed with large noses and smaller eyes and uneven-shaped heads. This design choice separates them from the white characters, who all are designed with more realistic proportions. All of these choices, from separating the Native Americans by their traditions to the intentional racist depictions of their character designs, it is clear that this cultural essentialism is used to portray Native Americans in a negative light, adding a racist undertone to a children’s film that the viewer may perpetuate later in life.

The Jungle Book: the Occident

The Occident cannot be defined simply as the counter to the Orient. Instead, as Said describes, “the relationship between Occident and Orient is a relationship of power, of domination, of varying degrees of a complex hegemony.”[6] The distinction made between these two areas always positions the Occident as morally and ideologically superior to the Orient, which warrants the study of the Orient by Occidental colonial scholars.

In the scene from The Jungle Book, Mowgli is portrayed as the ideal. The monkeys want to be like him because of the inherent traits he possesses as a human. If we take Mowgli as a representation of the Occident and the monkeys as a representation of the Orient, we can assume that the creators are showing this relationship as an idealization of the Occident and Western culture. This creates a problematic interpretation if we understand that to idealize the Occident through Mowgli is to idealize humanity, implying that anyone in the Orient or just not part of the Occident is somehow less than human and should try to be like Westerners. This reinforces the idea that marginalized groups have to adapt to white dominant culture to be successful. The song also includes the bear and the panther, Mowgli's caretakers and human-adjacent in the narrative, dressing up in costumes to pretend to be the monkeys only as a farce to take Mowgli back, which furthers Said's idea that the European/American in the Orient is their colonial identity first, individual second. This dress up is contingent on the fact that they will cease to be part of the Orient at some point and return to the Occident once they have what they need. This idealization and prioritization of Mowgli shows how the Occident and Western ideas are consistently idealized and prioritized over those of the Orient.

The Aristocats: cultural hegemony

Cultural hegemony can be defined as the sameness or the idealization of one dominant culture. Hall describes cultural hegemony as such: “it is always about shifting the balance of power in the relations of culture; it is always about changing the dispositions and the configurations of cultural power, not getting out of it.”[7] Cultural hegemony is not so much the pure domination of one culture for all of time, but the consistent changes made to the culture that make it appear as though one culture is not dominating, though in reality these changes keep this culture in power.

The balance of power, as Hall describes in relations of culture, shifts during the scene in The Aristocats. The scene begins with all the cats in the attic of the house, playing music and singing to their hearts content. However, by the end of the song, the aristocat family watches from the window of the attic as the other musicians fall through the floors of the house and walk out the door with their battered and broken instruments. The cats in the aristocat family are coded to be British or American, the epitome of imperial power. The musician cats are heavily racialized, with caricature-like designs and accents—with a throwback to the Siamese cat design from Lady and the Tramp. With this in mind, the musician cats walking out with broken instruments represents the way shifting culture aims to keep the white dominant culture at the top of the hierarchy, represented by the British and American coded cats staying in the attic—they are high class, literally and figuratively.

Bibliography:

Hall, Stuart. 1992. "Three What Is This “Black” in Black Popular Culture?" In Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora edited by David Morley, 83-94. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2018.

Said, Edward W. 2003. "Orientalism." Penguin Modern Classics. London, England: Penguin Classics.

Shohat, E & Stam, R. 1994. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle over Representation." In Unthinking Eurocentrism. Taylor & Francis Group. London: Routledge.

[1] Shohat & Stam

[2] Said

[3] Said

[4] Hall

[5] Hall

[6] Said

[7] Hall

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Said describes Orientalism in many different ways, but to sum them all up, in general Orientalism is a political vision of reality where the East is pitted against the West in an "us" versus "them" battle.[1] The disadvantage the East has is that any representation of it is coming from the perspective of a Westerner, the outsider looking in and attaching a certain perspective or value to what they see. Often, this results in the Orient being perceived as "irrational, depraved, childlike and different," and Europe, the US and the West being perceived as "rational, virtuous, mature and normal."[2] When linking to film, television and popular media, this intentional othering means that representations of the East and its people end up being just that: representations. There can be no "natural" depiction because there is no self-representation. Said brings this idea back to the sentiment of many Western Orientalist scholars/artists, who believe that "if the Orient could represent itself, it would."[3] Since it cannot (or never has the opportunity because of the emphasis on the Western "canon" of history and society), the interpretations and representations created by Western society will have to do. Having such a prevalent standards of accepted stereotypes entirely based on the interpretations of outsiders means that the field of Orientalism only exists because of the culture that produces it, not necessarily because of the inherent mystery "the Orient" presents to the West. From my understanding, Orientalism is not interested in being a field with accurate/authentic representations because that goes against the political purpose of the field, which--as Said puts it--is to "understand and control a 'different world'."[4]

The use of stereotypes in film and television can have positive and negative effects. They are useful in helping those from underrepresented groups identify with experiences shown onscreen. They attempt to unify a group under certain actions or traits, which can also be a detriment to the representation of these groups of people offscreen. Film and television are powerful mediums because they add visual elements to the dialogue that goes on between people in their everyday lives, which also means there is an expectation of what people will be seeing when they watch a piece of media. Shohat and Stam say that cinema doesn't "refer to or call up the world so much as represent its languages and discourses."[5] This artistic discourse is a "refraction of a refraction,"[6] the reproduced idea rather than the original. This is good for storytelling, as it functions as a vessel for subtlety and allegory, but when it comes to authentic and accurate representation of historically misrepresented groups, these layers distort the representation and disconnect the stereotype from the lived experience until it becomes disingenuous representation.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Bibliography:

Said, Edward W. 2003. Orientalism. Penguin Modern Classics. London, England: Penguin Classics.

Shohat, E & Stam, R. 1994. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle over Representation." In Unthinking Eurocentrism. Taylor & Francis Group. London: Routledge.

[1] Said

[2] Said

[3] Said

[4] Said

[5] Shohat, Stam

[6] Shohat, Stam

Reading Notes 10: Said to Shohat and Stam

To wrap up our studies of visual analysis, Edward W. Said’s “Orientalism” and Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation” provide critical paths to understanding the roles of race and representation play in our production and consumption of film, television, and popular culture.

How is orientalism linked to film, television, and popular media, and in what ways has standardization and cultural stereotyping intensified academic and imaginative demonology of “the mysterious Orient” in these mediums?

What role do stereotypes play in the representation of people, and in what ways can film and television change the perception of cultural misrepresentation?

@theuncannyprofessoro

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender and Sexuality Analytical Application

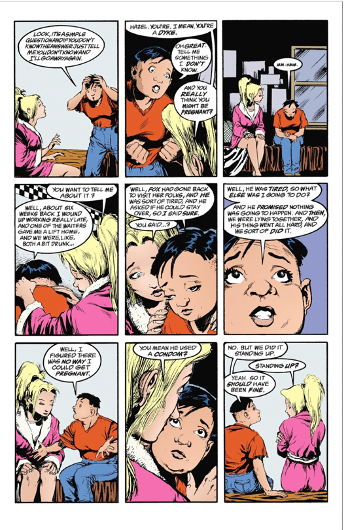

Butch:

Butch is a specific label within the identity of ‘lesbian.’ Typically, we understand ‘butch’ as a masculine woman, but this identity also functions as an identifier for other lesbians. Halberstam writes that “the butch stereotype, furthermore, both makes lesbianism visible and yet seems to make it visible in nonlesbian terms: that is to say, the butch makes lesbianism readable in the register of masculinity, and it actually collaborates with the mainstream notion that lesbians cannot be feminine.”[1] Due to this, the butch turns into a stereotype of the lesbian community rather than a subset of lesbianism. There are certain roles and acts that butches are allowed, and others that they are not, otherwise they risk breaking the mold set by society’s assumptions about the people behind the label.

In the above page from The Sandman: A Game of You by Neil Gaiman, there is a subversion of the stereotype of butches with the character of Hazel. When the reader sees Hazel, the visual cues lead them to believe that she is a stereotypical butch upon first look. And indeed she is a butch. What this page does magnificently is disrupt the hyper-masculine image of a butch lesbian by having Hazel come to her friend Barbie—a feminine straight woman—about possibly being pregnant. This question shakes up Barbie as well as the reader; two panels are devoted to Barbie rationalizing that Hazel had sex with a man in the first place. Due to the stereotype of butch lesbians being hyper-masculine and also typically having femme partners, the idea of Hazel with a man is an inherent disruption of the stereotype. By allowing a butch to act beyond what the stereotype dictates, A Game of You sets up Hazel as a butch that does not conform to the norm. Breaking out of this stereotype is important for butches, as it will allow the other identities within the lesbian community that are constructed around ‘butch’ to break away from butch and construct their own multifaceted identities as lesbians.

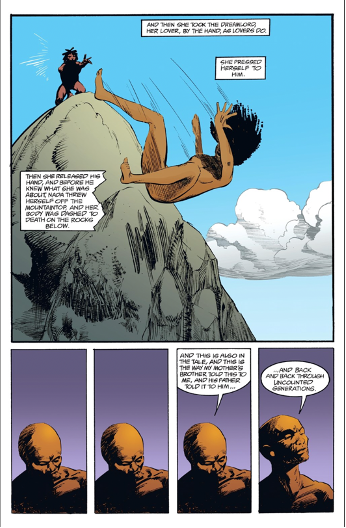

Male gaze:

The male gaze relates how women are viewed by men, specifically in film. There is an aspect of fantasy to the male gaze, which projects its desires onto the female figure. Mulvey states, “women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”[2] There is little agency for women in the male gaze because their bodies and actions are dictated by what the man viewing them wishes.

The above panel of The Sandman: The Doll’s House shows part of the tale that men in the community tell each other through generations. The composition of the panel shows the tale in the larger square panel, then the older man who is telling the tale in four skinnier panels below. The man in the tale—Dream—and the old man in real life are drawn from the same low angle, where Dream watches Nada, his love, throw herself off a cliff instead of choosing to stay with him. The parallel between Dream and the old man connects the men that tell the tale in the community to the main male character in the tale, solidifying Dream as the self insert character for men. This is interesting because Nada is set up as the main protagonist of the tale, and despite having more agency than Mulvey would describe women having under the male gaze, she is still a prize to be won by Dream within the story. However, with the rest of the context of this issue, the narrator tells the reader in text boxes bracketing the beginning and end of the comic that there are two versions of this tale circulating: the one the men tell each other—the one we the readers are told—and the one the women tell each other in a secret language the men do not dare to learn. By leaving out the women’s tale, The Doll’s House positions the reader with the men of the community, and by proxy, Dream. We are forced to participate in the male gaze by pure omission of the women’s side of the story, completely intentionally. Perhaps this was done to emphasize the lack of agency women have in telling their stories under the male gaze.

Queer gaze:

The queer gaze is in direct opposition to any gendered gaze that has been used to analyze cinema thus far. There is a tendency for psychoanalytical theories of viewing to be strictly gendered, and as the queer gaze rejects the gendered aspect of this type of viewing, it also rejects the more psychoanalytical aspects as well. Halberstam writes about the queer gaze in relation to Mulvey’s thoughts on the male gaze, calling for new terms with which to discuss cinema that were previously unimaginable, avoiding psychoanalytic terms. “Queer cinema, with its invitations to play through numerous identifications within a single sitting, creates one site for creative reinvention of ways of seeing.”[3]

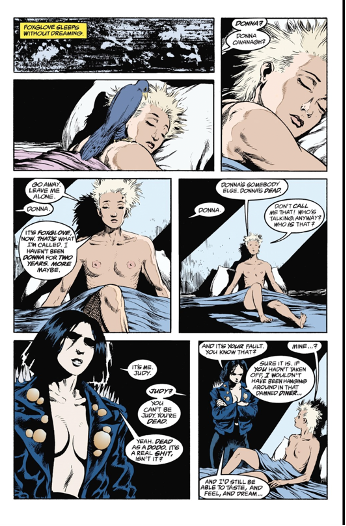

Through this page of The Sandman: A Game of You, Neil Gaiman depicts two women in a way that forces the reader to view them through the queer gaze. Subversions of typical gender norms cue the reader into the queer reading, but again it is the composition that aids the reader the most. The two panels in the middle of the page show the naked form of one of the characters, Foxglove. The angle is straight on, betraying no emotion, simply showing her as she is. Under the male gaze, this panel would have been used to sexualize Fox and the female body, but through the queer gaze, she is simply allowed to exist in her natural state. The next couple panels show Fox’s old lover, Judy. The first look we get of her is a low angle where her character overlaps with the border of the panel above. Her presence is already too big to be contained within a single panel, only emphasized by the leather jacket with spikes that enlarges her figure. Despite the clear indicators of femininity to a viewer—breasts showing and a feminine hairstyle—Judy manages to retain aspects of masculinity through her character design, though she isn’t quite ‘butch.’ Due to the subversion of what viewers expect from the male gaze in panels such as these, a less gendered form of viewing emerges from these panels—a queer gaze. Of course, this gaze is aided by the fact that the women were lovers; queerness is explicit and implicit here.

Gender norms:

Gender norms are established concepts or acts that group people into one gender or another. Typically, we see this most within the gender binary: male and female. Butler would have us recognize that such norms under regimes of power are realizable and not realizable. “This 'being a man' and this 'being a woman' are internally unstable affairs.”[4] Gender norms are standardized for those that fall within the gender binary, but they also are designed to be unattainable so that people are always trying to reach for a goal instead of reevaluating the value of such norms under a power regime.

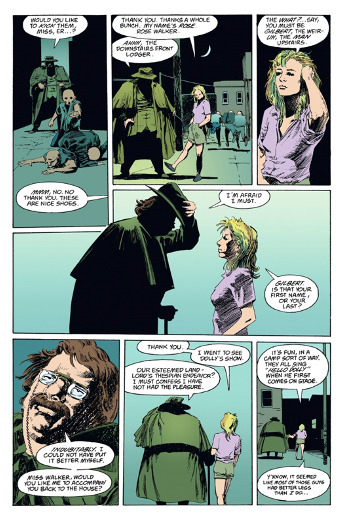

In The Sandman: A Doll’s House, gender norms are upheld through the interactions characters of different genders have. However, they are upheld through nontraditional ways, as the characters do not represent typical archetypes of each gender. In the above panels, the male character Gilbert saves the female character Rose from being mugged in an alleyway late at night. Gilbert embodies standards of masculinity like chivalry, protectiveness and kindness. Though the narrative allows him to show strength—as seen in the topmost left panel having beaten up the would-be muggers—he is not consumed by it as many male protagonists are in action films. Such protagonists may feel entitled to women and their attention having proved their physical prowess, but Gilbert is different. In that aforementioned panel, he is positioned behind the muggers, taking up less than half the panel. His strength is not romanticized, merely used in an act of kindness for Rose. She also adopts some classic tropes of female protagonists, such as being in danger and needing a man to save her. However, her status as ‘damsel in distress’ is more of a right place wrong time type of situation, where luck was on her side that Gilbert showed up to help. Her agency is never diminished; Gilbert even asks her if she wants to kick the muggers, but she responds, “No, no thank you. These are nice shoes.”[5] In the center panel, despite their height difference, Gilbert defers to Rose, bowing his head towards the woman standing tall in front of him. Showing the complexity of how people interact with gender norms proves Butler’s notion that there are attainable and unattainable aspects of gender.

Oppositional gaze:

The Black female oppositional gaze is a form of viewing cinema that Black women utilize in order to see themselves represented onscreen without negative racialized or sexualized representations. In bell hook’s work, she writes that Black women “saw cinema's construction of white womanhood as object of phallocentric gaze and choose not to identify with either the victim or the perpetrator.”[6]

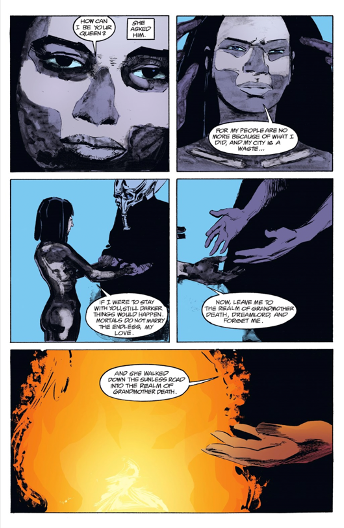

I chose two sets of panels for this term because I believe the first exemplifies the erasure of Black women and therefore the oppositional gaze, while the other represents Black women havin agency over their lives and stories, a direct installation of the oppositional gaze. The text boxes in the first panel detail the two different stories that are told in one Black community: the one passed generation to generation by men, and the other by women. We are never explicitly told the women’s versioni of the tale in the issue, which is a direct denial of the oppositional gaze. Without even being shown a single Black woman outside of the visualization of the tale the men tell each other, how can one even use the oppositional gaze? This is why the second set of panels is important; it gives Black women an opportunity to use the oppositional gaze, which is incredibly necessary since this story is being told by a man. Within the panels, the female protagonist Nada refuses to be Dream’s lover because of the consequences that fell upon her people when she slept with him once. He had threatened her with an afterlife of eternal damnation should she refuse him, yet in this set of panels, Dream does not speak. Only Nada speaks, asserting her beliefs and values before walking away from Dream and into the arms of Grandmother Death. This exemplifies hook’s assessment of the necessity of the oppositional gaze where Black women do not identify with the victim or perpetrator.

[1] Halberstam, Looking Butch

[2] Mulvey, Visual Pleasure

[3] Halberstam, Looking Butch

[4] Butler, Gender is Burning

[5] Gaiman, The Sandman: A Doll’s House

[6] hooks

Bibliography:

Butler, J. 1999. "Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion." In Feminist Film Theory. Edited by Sue Thornham. New York University Press: New York.

Gaiman, N. 1989. "A Doll's House." The Sandman. DC Entertainment: Burbank.

Halberstam, J. 1998. "Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film." In Female Masculinity. Duke University Press: United States.

hooks, b. "Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators." In Feminist Film Theory. Edited by Sue Thornham. New York University Press: New York (2009).

Mulvey, L. 1975. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." In Film Theory and Criticism. Edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. Oxford University Press: New York/Oxford (2009).

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Halberstam's example of a Latina butch in the movie Aliens (1986) is fascinating because it exemplifies the "positive image" that is rooted in pushing back against a conservative agenda. They write about the tough comeback as it "denaturalizes gender and literally returns the gaze, refusing to allow the white soldier to claim the place of universality and indeed humanity. Vasquez's butch performance hints at an "alien" logic of gender within which masculinity is as much a production of ethnicity as it is of gender and sexuality."[2] Though Vasquez is allowed to assert herself as a Latina and a butch, the film dictates that this identity of many marginalizations is too complicated, too confusing, for the popular culture, as she is the first victim of the film. Further marginalizing Latina butches, a Latina actress was not playing this role; instead, a Jewish actress played Vasquez. Why are Latina butches, who are massively underrepresented in popular culture anyway, further marginalized by not even being allowed to represent themselves onscreen?

One important thing to note with the political site to negotiate various identities in popular culture is the place in which the culture originates. Hall mentions that the shift from European high culture to American mainstream culture also includes the acknowledgement of ethnicities that make up the mainstream culture in the US. "American mainstream popular culture has always involved certain traditions that could only be attributed to black cultural vernacular traditions."[3] It is "America's ambivalent relationship with European high culture"[4] that sets the stage for marginalized identities to be represented and discussed within mainstream popular culture simply because of European high culture's inability to recognize the ethnic identities within it (up until very recently). But taking into account postmodernism's obsession with difference, Hall writes that there is also an "aggressive resistance to difference; the attempt to restore the canon of western civilization,"[5] which of course means white popular culture. By asserting itself as the dominant race, whiteness also pervades into our popular culture, shifting not just the narrative of culture but the lens through which we view it.

[1] Halberstam

[2] Halberstam

[3] Hall

[4] Hall

[5] Hall

Bibliography:

Halberstam, Jack. "6. Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film" In Female Masculinity, 175-230. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822378112-008

Hall, Stuart. "Three What Is This “Black” in Black Popular Culture? [1992]" In Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora edited by David Morley, 83-94. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478002710-007

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 9: Halberstam to Hall

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” and Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” link our inquiries into gender and sexuality with race and representation.

What examples of “positive images” of marginalized peoples are in film and television, and how can these “positive images” be damaging to and for marginalized communities?

In what ways is (popular/visual) culture (performance) a complicated and political site where various identities are negotiated, and how can cultural strategies make a difference and shift dispositions of power?

@theuncannyprofessoro

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Power and privilege clearly play a role in how people who are oppressed in different or compounding ways interact with each other. In "Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference," Audre Lorde describes how Black queer women are often shunned by both white women and Black women, though for different reasons. She says they are "caught between white women's racism and Black women's homophobia."[1] It is due to the way white women are allowed to interact with the privileges of the patriarchy because of their proximity to whiteness, and the deeming of queerness as "un-Black"[2] that causes Black women to separate themselves from Black queer women. These power structures inform how each group sees the other's differences. Lorde writes that we must begin to undo the structures implanted in our minds while also bringing down the institutions in our society in order to build new ones that allow our differences to be seen and accepted rather than ignored or destroyed.[3]

There are a variety of representations that support gender performativity, such as the color-coded toys we buy for our kids, appropriate hairstyles for each gender (this varies by culture, of course), and the tropes and stereotypes we see actors performing in film. Judith Butler says in her work "Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion" that it is due to the repeated acts done by people attempting to emulate a gender that actually creates the illusion of this gender.[4] With this, she also asserts that there is no such thing as a "natural" man or woman; rather, we have created this strict binary for ourselves--which is funny because the rules we must follow for each gender change every so often. Butler then continues on to say that heterosexuality, like gender, is "a constant and repeated effort to imitate its own idealizations."[5] In this sense, the natural order of the world, as dictated by a hegemonic heterosexual society, is also an imitation of what is thought to be "correct" or "societally acceptable."

Bibliography:

Lorde, A. 1997. “Age Race Class and Sex : Women Redefining Difference.” Dangerous Liaisons S.

Butler, J. 2000. "Gender is Burning: uestions of Appropriation and Subversion." In Feminist Film Theory. Edited by Sue Thorman. p. 336-348.

[1] Lorde, "Age, Race, Class and Sex"

[2] Lorde, "Age, Race, Class and Sex"

[3] Lorde, "Age, Race, Class and Sex"

[4] Butler, "Gender is Burning"

[5] Butler, "Gender is Burning"

[6] Butler, "Gender is Burning"

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 8: Lorde to Butler

In our continued discussions, Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and Judith Butler’s Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” provide further introspection into systems and definitions of gender and sexuality.

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mulvey begins her work by establishing that patriarchy and its ideology unconsciously influences film. Because women are subjugated and often reduced to vessels of sexual pleasure and reproductivity in a patriarchal society, it makes perfect sense that, as Mulvey puts it, "the paradox of phallocentrism in all its manifestations is that it depends on the image of the castrated woman to give order and meaning to its world."[1] Mulvey also writes that women are objects of male fantasy, forced to bear meaning rather than make it.[2] All these analyses point to the objectification of women under the male gaze, which does not allow a woman agency or mobility in the world around her.

Mulvey also articulates that Hollywood and other mainstream film has "coded the erotic into the language of the dominant patriarchal order,"[3] which only amplifies the already prominent male perspectives in society within the art form of cinema. With women as the 'passive' and men as the 'active,' the audience is able to align themselves more with the male gaze since the male protagonist is the one leading the plot.[4] This order always subjects women to the male gaze and displays their bodies, whether the full thing or just bits and pieces made to look erotic on camera, in such a way that they are made to be looked at, never the ones doing the looking.

Because film at its inception was created to uphold a white supremacist system, black viewers "experienced visual pleasure in a context where looking was also about contestation and confrontation."[5] It was then the oppositional gaze that responded to that by developing independent black cinema.[6] But there are differences between how black men and black women view cinema, according to hooks. "In their role as spectators, black men could enter an imaginative space of phallocentric power that mediated racial negation."[7] Due to this, black women less often found themselves relating or even seeing something resembling themselves or their experiences on the silver screen. To describe this phenomenon, hooks writes that black women "saw cinema's construction of white womanhood as object of phallocentric gaze and choose not to identify with either the victim or the perpetrator."[8] This is the development of the oppositional gaze, something that empowers black women to construct her worldview onscreen outside of the white patriarchal default cinema ascribes to.

[1] Mulvey

[2] Mulvey

[3] Mulvey

[4] Mulvey

[5] hooks

[6] hooks

[7] hooks

[8] hooks

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16, 6-18.

hooks, bell. The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators. South End Press, 1992.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 7: Mulvey to hooks

Shifting our visual analysis and critical inquiries to gender and sexuality, we will begin our explorations with Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and bell hooks’s “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.”

How does the spectacle of the female image relate to patriarchal ideology, and in what ways do all viewers, regardless of race or sexuality, take pleasure in films that are designed to satisfy the male gaze?

How do racial and sexual differences between viewers inform their experience of viewing pleasure, and in what ways does the oppositional gaze empower viewers?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application 4

Collective Catharsis:

In Fanon’s work, “The Negro and Psychopathology,” he describes collective catharsis as “an outlet through which the forces accumulated in the form of aggression can be released.”[1] What is truly incredible is that catharsis can be achieved through multiple means: games, therapy, even watching film and television.

In the X-Files episode “Squeeze,” there is a fairly straightforward example of such a catharsis. When the old sheriff picks up his newspaper and reads the story about Toomes being arrested and sentenced, it brings about a look of incredible relief and joy on his face (Longstreet, 1993, 39:45). For so long, he had been obsessed with catching Toomes that he nearly ruined his career by continuing to pursue the case. This moment of realization that he can rest easy knowing that what he set out to do was accomplished has a cathartic aspect to it because it was set up earlier in the episode (Longstreet, 1993, 26:57). Without the context for his continued chase of Toomes, the relief he feels having seen his arrest wouldn’t have been nearly as impactful for the viewer. This setup and payoff is required to effectively tell the story because it wouldn’t be as cathartic if the viewer wasn’t as invested in experiencing that catharsis as well.

Unheimlich:

The unheimlich is the opposite of the heimlich, which is the German word for ‘familiar.’[2] It also describes the hidden or unknown state of things. Freud describes heimlich as a word that develops an ambivalence, until it coincides with the unheimlich, which is not entirely understood.[3] For this reason, the unheimlich is an important part of what makes something uncanny.

The unheimlich in the scene where a man is murdered around halfway through the episode (Longstreet, 1993, 20:27) shows itself in the way the scene resembles the opening scene. There, the murder of the man is played like a straight up serial murder, but with the added context of the investigation from the part of the episode that has happened already, the heimlich or ‘familiar’ parts of the murder start veering closer and closer to intersecting with the unheimlich. These elements appear specifically with the showing of Toomes’ supernatural abilities—think the way he squeezes himself down the chimney (Longstreet, 1993, 22:01). Though we have already seen this before—it was even the same sort of older business man getting murdered—there are subtle differences that push our understanding of it to unfamiliar territory. Also, the familiar parts of the setting are made unfamiliar by way of the audience knowing that Toomes will appear at some point to murder the man. Each corner could hide a murderous man, and the fireplace, once a place of warmth and comfort, could hide Toomes’ glowing eyes in its shadows. This aspect of unheimlich transforms this scene in a way that doesn’t make it feel repetitive, as it is essentially the same as the opening murder scene.

Uncanny:

In his work “The Uncanny,” Freud puts forth a few ways to define the word ‘uncanny.’ He describes it as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar,” which arises out of our repressed memories.[4] This is where the unheimlich, or ‘unfamiliar’ comes in; that which is unfamiliar but is now being brought to the surface of our minds is what makes something feel uncanny.

During the X-Files episode “Squeeze,” the unheimlich appears during the part of the episode where Scully (Gillian Anderson) and Mulder (David Duchovny) go to investigate the old apartment where Toomes supposedly lived in the early 20th century (Longstreet, 1993, 30:16). The main room of the apartment definitely has a creepy vibe—in the way that abandoned rooms in abandoned buildings usually do—but it’s not quite uncanny. This lack of uncanny vibe is remedied when the characters travel underneath the building into what can only be described as a lair. The surroundings underground are covered in newspaper clippings that have been spit-balled onto the walls, and the artifacts and personal effects that Toomes takes from his victims are enshrined in the center (Longstreet, 1993, 32:06). It is these household and personal items that truly add to the uncanny feeling of Toomes’ lair. Surrounded by all this grime and grossness, coupled with the horrific fact that the two main characters are in the belly of the beast, so to speak, the personal items lend that familiarity, that “once very familiar” aspect that Freud mentioned.[5] These items tie the creepy supernatural setting and story back to a grounded place in reality, which is what elevates the creepy vibe into an uncanny one.

Mirror stage:

The mirror stage was theorized by Lacan in his work, “The Mirror Stage as a Formative Function of the I.” In the text, Lacan describes how an infant, before being able to walk or talk, can recognize itself in the mirror and can understand that the image it is seeing is indeed itself.[6] This is the first instance of the I that humans can understand, and it is the purest form of the I since it cannot be diluted with words since the infant has no grasp of language.

One of the scenes towards the end of the episode exemplifies the mirror stage quite well. Once Toomes has been imprisoned, a guard comes to give him food, sliding it through a little opening in the door. Toomes immediately latches onto this opening as a sign of hope, with the POV shot showing the opening as a bright white light, almost like an escape into a different world (Longstreet, 1993, 41:04). With Toomes’ supernatural powers, that opening very well could be the way he escapes. However, I relate this to the mirror stage because, despite the lack of a mirror, seeing the opening awakens a primordial realization in Toomes, one that resembles that of an infant seeing itself in the mirror for the first time and realizing the reflection is itself. Toomes’ supernatural powers are certainly a core tenet of his being, and so seeing an opening where he can use those powers in an otherwise baren room might feel like the pure I that Lacan mentions when an infant sees its reflection.

Disalienation:

Fanon proposes the method of disalienation as an opposition to the common practice of alienation. In disalienation, race relations might cease to exist, and people will look at each other and focus on understanding one another.[7] Disalienation begins with a blank slate where two races can interact with each other, this blank slate being a product of the histories of the two groups.

Though there are no characters of color in the episode of the X-Files, the concept of disalienation could potentially be applied to the different branches of the FBI. There is the branch that handles most crimes, and the branch that Mulder and Scully are a part of, the supernatural branch. Throughout the episode, the disdain that other investigators hold towards the supernatural branch is made clear—they think Mulder in particular is “spooky” (Longstreet, 1993, 7:00)—and it complicates the way the case gets solved. Fellow FBI agent Tom Colton with the “normal” branch even goes so far as interfering with Mulder’s stakeout because he doesn’t believe that he should get the credit. However, in the scene where Colton tells Scully that he recalled the men on the stakeout, she stands up for Mulder and reasserts herself as a prominent member of the supernatural branch (Longstreet, 1993, 34:54). I would say this moment where Scully, who was drifting away from Mulder and the supernatural branch at the beginning of the episode, comes into her own and rebuffs her identity as part of the supernatural branch is the starting point to create the blank slate where the two groups may be able to interact.

[1] Fanon

[2] Freud

[3] Freud

[4] Freud

[5] Freud

[6] Lacan

[7] Fanon

Bibliography:

Fanon, Frantz. 2008. Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Press.

Freud, Sigmund. 1925. The Uncanny. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Lacan, Jacques. 2006. The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Uncanny to me is a feeling that emerges when I see something that looks right but feels wrong somehow, but I can't quite put my finger on what. Freud would say that the uncanny harkens back to old memories--"that class of terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar."[1] That creepy-unfamiliar feeling manifests as a morbid form of anxiety that comes from repressed memories of our past. An experience that appears to be uncanny might be something creepy and unfamiliar but not rooted in those repressed memories.

A personal neurosis occurs when the mind cannot truly begin to process the differences between the many images of the human it is attached to from different outputs. The "ideal-I" becomes separated from how the person can express themselves with words.[2] But this separation becomes less unbearable when put in contact with social passions, which can distract from the moral dilemma between the "ideal-I" and the "social-I."