Text

(This post will contain mild spoilers for Yellowface. There will also be brief mentions of racism.)

Yellowface was a breath of fresh air!

Hello, welcome, it’s been a while, hasn’t it? I honestly thought this blog would be abandoned to inactivity until now when I received renewed vigour to write for it. The cause is simple, really. I finally found another book I thought was worth talking about regarding its portrayal of women.

Now this may surprise you but we don’t particularly enjoy expelling negative energy on books. We started this blog out of a naïve hope that perhaps we would be put in touch with like minds and find books that speak to us. Fast-forward a few years on and that hope was dashed. My co-partner had grown busy with other pursuits and equally had few words to speak on anything literary, and we packed up this blog prepared never to update it again.

That is, until, my saving grace came in the form of a most unexpected source.

I had heard whispers of Yellowface prior to its publication but I admit after reading its premise and a few advanced reviews, it didn’t seem like anything I would be interested in. How it pleases me to be wrong in this instance! And to have taken a chance after having seen a few friends speak its praises. The premise to Yellowface is a simple one: set in a contemporary America, Juniper Hayward steals the manuscript of her deceased Asian female friend and passes it off as her own, and this callous act of self-serving ego rockets her to stardom.

Juniper Hayward is one of the best female protagonists I’ve read in quite a long time.

Before I continue, I want to make a few things clear: Juniper Hayward is no feminist icon. She is racist. She is egocentric, prideful, catty, self-interested. She is, in all respects, the villain of the story and the orchestrator of her own misery. And yet… and yet… she compelled me. She reflected an ugly side of being an artist I longed to see portrayed by a woman. While she is the furthest thing from an aspirational and awe-inspiring individual she was so startlingly human, so flawed, so hungry, that I couldn’t get enough of her. I devoured Yellowface in the span of two days and afterwards I was left utterly enthralled by Juniper and Athena both and their parasitic, competitive friendship.

Deep down, I’ve always suspected Athena likes my company precisely because I can’t rival her. I understand her world, but I’m not a threat, and her achievements are so far out of my reach that she doesn’t feel bad squealing to my face about her wins. Don’t we all want a friend who won’t ever challenge our superiority, because they already know it’s a lost cause? Don’t we all need someone we can treat as a punching bag?

This is the sort of representation I was looking for! Women who are deeply driven by their own want and ambition, compelled to succeed until it takes them to unprecedented heights (or leads to an almighty fall). I truly commend Kuang for bringing these women to life, setting them in a book filled with equally dimensional and awful female side characters, with nary a prominent male presence to be found unless they serve the narrative. It was a genuine pleasure to read about Juniper and her desire to be recognised for her writing accomplishments, to create and leave something behind that was bigger than herself:

A musician needs to be heard; a writer needs to be read. I want to move people’s hearts. I want my books in stores all over the world. I couldn’t stand to be like Mom and Rory, living their little and self-contained lives, with no great projects or prospects to propel them from one chapter to the next. I want the world to wait with bated breath for what I will say next. I want my words to last forever. I want to be eternal, permanent; when I’m gone, I want to leave behind a mountain of pages that scream, Juniper Song was here, and she told us what was on her mind.

Juniper Hayward is a protagonist on par with Humbert Humbert. A loathsome figure full of pitiful self-excuses and delusional rationalisations for the wrongs they commit. You feel disgust with them, you feel for them, you yearn to understand them, but what you can never do is ignore them.

Plagiarism is an easy way out, the way you cheat when you can’t string words together on your own. But what I did was not easy. I did rewrite most of the book. Athena’s early drafts are chaotic, primordial, with half-finished sentences littered all over the place. Sometimes I couldn’t even tell where she was going with a paragraph, so I excised it completely. It’s not like I took a painting and passed it off as my own. I inherited a sketch, with colors added only in uneven patches, and finished it according to the style of the original. Imagine if Michelangelo left huge chunks of the Sistine Chapel unfinished. Imagine if Raphael had to step in and do the rest.

And what I love most is that, penned by an Asian woman like Kuang, there is no chance for Juniper to escape accountability for her vile misdeeds. The author holds her up in all her contemptible glory, with no veneer of justification to be found, and invites you to observe and cast your judgement. She tapped into the gnawing resentment that eats away at every writer in the publishing industry, each of us all clawing for the scraps of recognition those at the table see fit to toss our way until we all turn on each other. Why her? Why not me? Is it because I am not pretty enough? Not charismatic enough? Am I simply too blandly white and heterosexual? Am I simply too unpalatable for the masses? On and on it goes, the gears turning, powering the engine of jealousy until it churns out a monster like Juniper.

The attacks on the publishing industry and how it commodifies and weaponises identity to serve capitalist interests were particularly salient and incisive from Kuang, I like how she tackled both sides of an argument, exposing both of their respective shortcomings, and left no one unscathed.

She’s done this in all her other novels. Her fans praise such tactics as brilliant and authentic—a diaspora writer’s necessary intervention against the whiteness of English. But it’s not good craft. It makes the prose frustrating and inaccessible. I am convinced it is all in service of making Athena, and her readers, feel smarter than they are.

But best of all, I loved how much the story was so singularly focused on Juniper’s ambitions. There was no looming romance in the background threatening to infringe on the narrative. Juniper never took the chance to lament her lack of a traditional lifestyle, if anything, she scorns it.

I couldn’t stand to be like Mom and Rory, living their little and self-contained lives, with no great projects or prospects to propel them from one chapter to the next. I want the world to wait with bated breath for what I will say next.

However, like all books, there are shortcomings. I won’t detail them here as they are not relevant to the nature of this particular post and don’t detract enough from the positives to bear mentioning. All in all, Yellowface was a pleasant and welcome surprise and I heartily encourage people to pick it up if you’re interested in reading about women wallowing freely in their dark sides.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

fridging is a specific trope with certain characteristics, it doesn't mean "character who died". for one its name is "woman in refrigerators"! it refers specifically at the ways women are made to suffer in fiction to further the storylines of men. AKA if a.) the dead character isn't a woman, or B.) the dead character IS a woman but the storyline isn't mined for manpain and a man's development? doesn't count.

371 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why would you want women to have more power in an unjust system? Because the unjust systems are the only ones available. Because the exclusion of women from power is one source of this injustice. Because women gaining power is a prerequisite for them to become free. “Why would you want women to have more power in an unjust system?” isn’t a bad question. But it raises another one: Just how perfect does the world have to be before women will deserve to take their equal place in it?

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

More from Kathleen Turner’s 2018 Vulture interview

70 notes

·

View notes

Link

really loved this </3

#article#word of warning for a graphically described sexual assault#but a very important read all the same

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In the film "Portrait of a Lady on Fire," the protagonist is a female portraitist in 18th century France. She is portrayed as a respected professional, with significant personal and economic independence. Could a woman in 18th century Western Europe really have a professional career as an artist?

Yes, certainly! There were a number of respected eighteenth century female artists.

The most famous is Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), the daughter of significantly less famous artist Louis Vigée, who died when she was little; she married a (male) painter as well. Relatively early in her career she became a portraitist to the nobility, and by the 1780s she was painting Marie Antoinette herself and a member of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpting. She fled the French Revolution and took up posts in other royal courts around Europe to support herself while keeping her stock high.

Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) is another very big name in the eighteenth century art world. She was Swiss, and the daughter of a painter who trained her while they traveled around Europe, leading to her career starting at an early age. She was a member of multiple academies in different regions as well, from Florence to England.

But there are far too many for me to summarize them all: here is Wikipedia's category page for "eighteenth century women artists" on the site.

The question of how people could hold particular beliefs about women's inferiority to men while also having women with power or standing in their society comes up relatively frequently on AskHistorians. The fact is that gender is infinitely more complicated than a simple oppressed/oppressing dichotomy; rather than being completely marginalized by the men who dominated the art world of the eighteenth century, they found ways to make themselves part of the structure as well, though said men would rarely consider them as good as the best male artists. Several of the chapters in Women and Material Culture, 1660–1830 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) speak directly to the issue, making the point that women's participation in the arts went along with perceptions of what could be classified as "women's work".

Watercolors, miniatures, and wax- or cameo-carving, for instance, were easy for people to accept as fields for women because they were seen as delicate, requiring a graceful hand - similar to the way that once women began taking up positions in offices, using a typewriter was reclassified as something women would be inherently suited to as it was similar to playing the piano, a common feminine accomplishment. (Really!) People of the eighteenth century also found it relatively easy to accept "sculptresses" who did the creative work modeled in clay and had a man carve it in marble (though they were open to criticism of allowing those male assistants more creative license, and therefore the notion that they weren't really the creators of the works), and were more suspicious or scornful of women like Anne Damer (1748-1828) who wielded a hammer and chisel themselves, from remarks about the quality of their work to caricatures portraying them as too masculine.

But, that being said, they were still allowed to do their work, and were still commissioned and paid to do it, because their art was valuable and wanted. The average person doesn't not know any female artists from before 1850 because there weren't any, but because they were never allowed to be considered at the very top of their fields, and therefore weren't included in later retrospectives of the art canon.

374 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yayoi Kusama, Cosmos, 1993

signed, titled and dated ‘Yayoi Kusama 1993 “COSMOS”’, inscribed in Japanese (on the reverse)

acrylic on canvas

162 x 130 cm. (63 ¾ x 51 1/8 in.)

more

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t know if you have read it or if you do reviews of any genre but would you possibly do a review of the Bridgerton book series, it frustrates me how so many claim for it to be feminist (tbf the author has never claimed this). Or that it is for woman by woman and focuses on female desire. It’s frustrating bc Bridgerton like so many hr novels , contains so much misogyny towards other woman who are not the main girls. Female desire is fine for the female character but other woman who partake in it outside of love or marriage are viewed badly. Despite the fact that the men are often rakes and sleep with the whole country but it is viewed as a sign of virility to them. The fact that the main hero has viewed every single other woman as objects and has used, exploited lower class woman and is somehow praised for that is to much for me. I hope this isn’t controversial but a lot of the books and romance tends to feed into that one special girl who is so good and pure that she alone can touch the dark mans heart and she is so special that he actually feels something for her.

There is so much more as well- how the Bridgerton heriones are not like other debutantes and manage to have more sympathy for these rich lords than they do for woman like them. Woman who pretty much have been raised from birth to care how they look and who they should marry. Not to mention the way that the author makes it as if they and their society mamas are harassing these lords for marriage is just frustrating. There is no sympathy for the situation these woman are in, only scorn.

Hello!

We haven't read this book series, no, and your description leaves little doubt as to whether we would enjoy it. We do accept recommendations wholeheartedly and our ask box is open to sharing one's frustration with a work, even if we do not know said work ourselves - as we want more discussions to arise about misogyny first and foremost.

However we would rather search for good books than spend too much time with disappointing ones. Mediocrity and misogyny abound; if we are to seek such content actively, we will be left exhausted, hopeless and dulled. Lessons can always be learned from flawed works, but true inspiration and insight strike from mastery.

(The works we discussed or reviewed were never opened with spiteful intent. The extent of their misogyny was, each time, stupefying and against our best hopes.)

With that said, your frustration is of course all too well understood... once again, it is stunning how easily your words could be applied to myriad of other works. It is all but a script - we know it, we've all seen it, everywhere in this world... but speaking about it, hightlighting the patterns, rejecting those works and uplifting the ones doing justice to female characters and their romances, that's how we will come closer to unraveling it.

Hence we cannot write about this series... yet it seems you could! You seem to have grasped the failings of it and articulated them quite well. If you do have a review of it, or feel like writing one, don't hesitate to send us a link. We would be happy to reblog such an analysis or link to it!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Marsh is not swamp. Marsh is a space of light, where grass grows in water, and water flows into the sky. Slow-moving creeks wander, carrying the orb of the sun with them to the sea, and long-legged birds lift with unexpected grace—as though not built to fly—against the roar of a thousand snow geese.

Then within the marsh, here and there, true swamp crawls into low-lying bogs, hidden in clammy forests. Swamp water is still and dark, having swallowed the light in its muddy throat. Even night crawlers are diurnal in this lair. There are sounds, of course, but compared to the marsh, the swamp is quiet because decomposition is cellular work. Life decays and reeks and returns to the rotted duff; a poignant wallow of death begetting life. »

— Delia Owens, Where the Crawdads Sing

85 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Women in Restoration by Isabella De Maddalena

39K notes

·

View notes

Note

Y’know I really disagree when you say “Alina got her happy housewife ending”

That was what Alina wanted. She didn’t want to lead the second army. We see repeatedly in the text how she craves a normal life with the boy she loves. Feminism isn’t saying every woman should be sole powerful leader, it’s saying women have the right to choose there own path. Alina chose hers, the one she’s always wanted.

Then Alina should not have been the protagonist of a fantasy series that she clearly didn't even want to be a part of from start to end. She and mal should have been deleted from the story all together. And Bardugo should have written a military wife romance for people who are into that kind of thing 🤷🏽♀️

Women in REAL LIFE can live their lives however they please. That's feminism. However, Alina is not real. She's a character. And she's a very weak plot device grade character with a "strong female character" aesthetic with light bulb powers she neither wants nor ends up having and can't even stand on her own two feet without a man being her crutch. Darkling hands her a character arc in the beginning of every book, Mal literally drags her through it doing 99% of the work for her, and then the darkling returns to manufacture illogical drama for her to get horrified by and getting another excuse to run away from the story. Sometimes it's Bagra or Nikolai telling her what to do.

Her relationship with Mal is extremely codependent and both of them needed to lose what little personality traits they had to begin with in order to end up trapped in a romanticized version of the past. Also, she literally has no wants outside of her crippling codependecy on Mal. And since she's a fictional character and the writer explicitly made all these choices for her PROTAGONIST and essentially wrote her like some sexist man would write a damsel in distress personality less love interest...I'm afraid this is a very 404 feminism not found situation for me.

#others' posts#The Grisha Trilogy#important to note that these are written characters#and thus the author made choices for them#we cannot treat them as if they are real life breathing women#when analysing the failings of their narrative

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the beginning of The Craft, when the extent of the girls’ power is making a boy fall for one of them, making another’s burn scars disappear so she’ll be “beautiful on the outside, as well as in,” and making a racist blonde bully’s hair fall out, things are all well and good. That’s a level of power that’s acceptable for them to have; just the right amount to be “badass” but not enough to be threatening. But Nancy steps over the line when she starts killing off abusive men—the drunk and belligerent stepfather who grabs her ass and hits her mother, and the possessive jock who tries to rape a member of her coven. She becomes a threat when she fights back and demands physical and sexual autonomy for herself and other women.

As a culture, we love powerful women as an idea—as a marketing angle to sell anything from statement tees to home goods, makeup to coworking spaces—but still balk when a woman is unsatisfied with the empty platitude of “empowerment” and steps up to demand real power.

This is exactly what has always scared people about witches. Witches don’t ask for permission or play by the rules; they find power within themselves and use it to shape their lives and the world around them. Witchcraft is threatening to the status quo because it’s a spiritual practice that doesn’t rely on power concentrated in clerics, or houses of worship that can collect poor people’s tithings. There’s no unified law with rules passed down from the powerful to the followers. It allows for more autonomy than the powers that we are comfortable with.

Women who burned at the stake for being “witches” were usually guilty of nothing more than rejecting societal norms, posing an implicit or explicit threat to the Puritanical, patriarchal power structure. If a woman lived alone, her independence was seen as sinister. If she didn’t go to church, if she looked at a powerful man the wrong way: witch. Stories about witches have always been cautionary tales to women, about how quickly your community will turn on you if you step out of bounds.

Lilly Dancyger, I’m Done With Cautionary Tales About Women and Power

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

God says to Eve upon her departure, “Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you,” but when I read this, I see instead the curse in abbreviation: Your desirewill rule over you. (Genesis 2:16) Eve is cursed with desire bound together with her hunger, as if to say the punishment for wanting is to keep wanting. In this way, ideas of desire and hunger, propriety and sin become tied together.

I find myself reflecting on other women depicted as monstrous for their hunger; Pandora and her box, Snow White and her apple. The appearance of lacking desire goes beyond the bounds of etiquette or being ‘ladylike’ and instead crosses into the realm of a moral imperative. Which is to say, a just, good, decent woman is a woman who is free of any type of hunger, be it physical hunger for food, hunger as desire, or hunger as ambition. Conversely, a woman sickened with sin is one who is riddled with said hungers, reduced to a gaping mouth never satisfied

Nina Coomes, On Eve’s Temptation and the Monsters We Make of Hungry Women.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sady Doyle, Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers: Monstrosity, Patriarchy, and the Fear of Female Power

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you mean? with the feminine monstrous?

I mean complete, unreserved, unapologetic cultivation of all that is messy, ugly, condemned and reviled for women. I mean no more being forced to walk an exhausting, endless tightrope of crippling shame and fear, self-loathing and self-surveillance, no more endlessly checked and restrained desires - no more being punished for those desires. I mean no more of the toxic, quietly stifled rage that we know so intimately for all of our lives. I mean totally unleashing and no giving a damn anymore what it looks like. I mean ‘liberation’ first and above all else, not ‘empowerment’. I mean teeth and unruly hair and downright fabulous grotesquery. I mean embracing the fact that, after centuries, a grand, collective Snap is coming and it is going to be ugly and absolutely fucking glorious.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“all too often women believe it is a sign of commitment, an expression of love, to endure unkindness or cruelty, to forgive and forget. In actuality, when we love rightly we know that the healthy, loving response to cruelty and abuse is putting ourselves out of harm's way.”

- bell hooks, (1952-2021)

11K notes

·

View notes

Photo

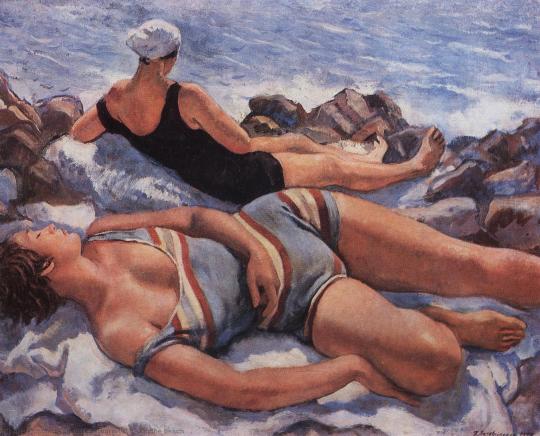

Zinaida Serebriakova – On the Beach (1927)

899 notes

·

View notes