Photo

Mottled sea stars (Evasterias troscheli) and flat bottom sea stars (Asterias amurensis) clinging to the ferry pier pilings in Homer, Alaska.

15K notes

·

View notes

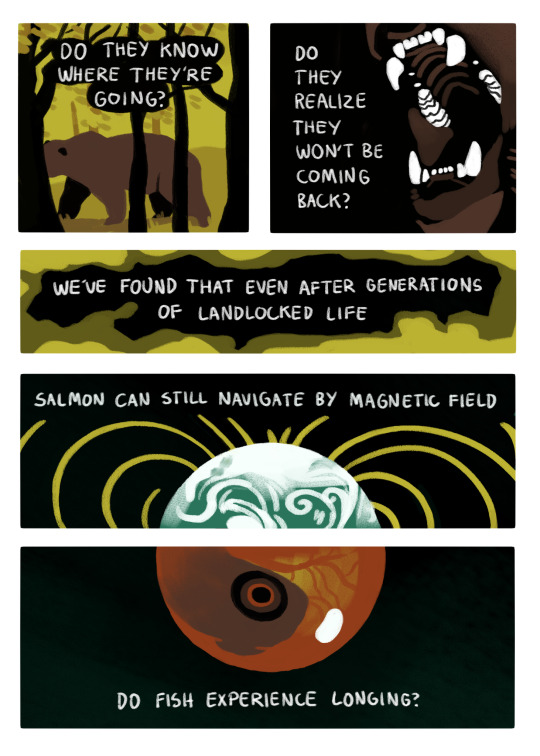

Text

i love when very small bats open their mouths real big and it takes up the entirety of their faces, you can barely even see their eyes

24K notes

·

View notes

Photo

What does the Kermode bear (Ursus americanus kermodei) have in common with red haired-humans? Its cream-colored fur—sported by about 1/10 of the population—is due to a recessive MC1R gene, the same gene associated with red hair in humans! The Kermode bear is a unique subspecies of the North American black bear that can be spotted in British Columbia. While these bears are sometimes mistakenly thought to be albino, they have dark paws and dark noses.

Photo: Maximilian Helm, CC BY 2.0, flickr

https://www.instagram.com/p/CXaOu2SMWas/?utm_medium=tumblr

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

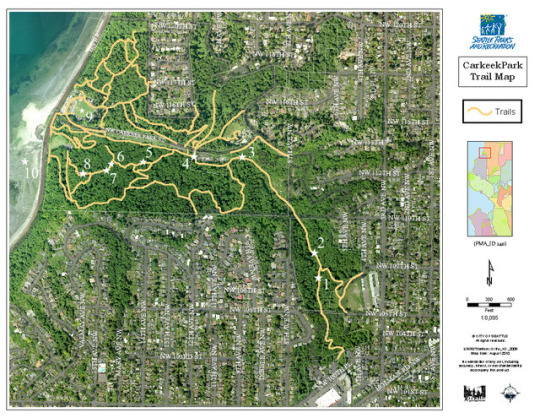

A list of SO many species I saw at my time at Carkeek!

0 notes

Photo

Carkeek Park lies on the coast of the Puget Sound not even 10 miles north of downtown Seattle. Opened in 1918, Carkeek Park originally overlooked Pontiac Bay on Lake Washington. The land was donated by Mr and Mrs Morgan J Carkeek. Mr Carkeek was a builder and contractor who worked in Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia. The original Carkeek Park was just 23.2 acres and designed as an overnight camp facility with a bunkhouse and dining hall. In 1926, however, the federal government bought the Sand Point region for use as a Naval Air Station. With the $25,000 Carkeek received from the government, he offered to buy land for a new park. Petitions were put in for Piper’s Canyon, where the Piper family homesteaded at the time and after whom the canyon, creek, and orchard are named, to be the site of the new park. [This land was originally used by the Shilshole band of the Duwamish, among other peoples. Their original name for Piper’s Creek was "Kwaateb," meaning "leave it alone."] The Park Board, however, believed that a new park was not needed or wanted, and the money from the old Carkeek Park site would be better used rehabilitating current parks. City Council went against the Board’s position and bought Piper’s Canyon for $100,000 on top of the $25,000 from Mr Morgan Carkeek. The Council also put in an order to purchase Matthews Beach, but that sale was not finished until 1951. Carkeek Park opened where it stands today in 1928. The current park is 220 acres of forests, meadows, an orchard, wetlands, creeks, and a beach. The following walking tour will highlight some of the natural history within Carkeek Park.

http://clerk.seattle.gov/~F_archives/sherwood/Carkeek.pdf

http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20040815&slug=carkeek15

http://pugetsoundgis.com/projects/

https://www.seattle.gov/parks/find/parks/carkeek-park

0 notes

Photo

Stop 1: Fungi

Forgoing the main entrance to Carkeek Park, this tour begins walking due north along Piper’s Creek Trail from the Eddie McAbee Entrance off NW 100th Place. This entrance was named in honour of Eddie McAbee who died due to complications related to diabetes at the age of 30. His father, Dick McAbee, was a builder, philanthropist, and humanitarian. Along with donating the land for the park entrance in 1953, he co-chaired a funds drive to move the Ballard General Hospital to a more appropriate location. This hospital is known today as the Swedish Medical Center.

As you walk along the trail to the first stop, keep your eyes focused on fallen logs and old tree stumps. Especially after a recent rainstorm, fungi litter the soft, damp wood. Fungi are the only organisms that can digest word and are therefore critical to the cycle of trees in any forested environment. Although many species of fungi can be found along this trail, one of the most prevalent across North American forests is Trametes versicolor, also known as turkey tail fungi. This species is named for its fan-like projection that resembles the tail of a turkey. T. versicolor fungi, as the species designation “versicolor” implies, vary in colour, but are most typically brown or perhaps a cinnamon-brown.

http://crownhillneighbors.org/wp/2010/07/gifts-from-the-builder-the-eddie-mcabee-park-entrance/

0 notes

Photo

Stop 2: Wind-felled Logs

Follow Piper’s Creek Trail across one bridge and then another. Stand on the second bridge over Piper’s Creek when you arrive at this site. If you face south (to your left, if you are following the tour in order), you will see many fallen logs stretching across Piper’s Creek. These logs were not felled by human hands, but instead were blown over, possibly weakened by old age or low structural integrity from other disturbances. Now, these trees are home to various invertebrates, offer food for decomposer fungi, and provide a way for animals to cross the creek without having to swim.

When trees fall in an old growth forest, they leave gaps in the canopy. Sun again can reach the understory, which allows young saplings to grow in the clearing. These saplings will eventually be tall enough to close the canopy, again shading the majority of the understory. Abiotic disturbances, which also include fires, floods, ice storms, etc., allow the forest to recycle some older trees and other plants to provide space for younger plants to grow. Even if a forest seems entirely devastated from one of these natural disasters, life will soon reappear and the forest will start again.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stop 3: Erratics

Continue along the trail, crossing the creek a few more times. If you come to a fork in the trail, you’ve gone too far.

17,000 years ago, Seattle was buried under the Puget Lobe of the Vashon Ice Sheet. The Puget Sound Region was compressed under 3,000ft of ice. Effects of this glaciation include drumlins, hill-like ridges which run generally north/south across the Region; moraines, gravel depositional zones that outline as far as the glacier reached; and erratics, huge boulders of non-native rock that fall out of the ice as a glacier melts away. Erratics frequently travel hundreds of miles with the glacial ice before being dropped. Standing in this location you can see two erratics, one with some tasteful moss and less tasteful spray-paint, the other directly opposite across the trail, essentially cloaked in moss and hidden amidst brambles and ferns.

These are small erratics, as many are easily the size of small homes. They are still, however, strong evidence that a glacier at one point covered the region. The strength of the glacial ice knocks massive chunks of rock free. These chunks are frozen into the glacier and carried along as the glacier expands. When the glacier melts, it reaches a point where the ice is no longer strong enough to hold the weight of the massive boulder, and the erratic falls out of the glacier, usually to not be moved again. Erratics are far too large to be easily moved by human activity. The rock can be tested to determine its place of origin, further confirming that a given boulder is the product of glacial activity.

0 notes

Photo

Stop 4: Great Blue Herons

As you follow the creek to the next stop, keep a look out for wading great blue herons. Birds have this funny habit of not staying still. They have been seen along the creek, but rarely in the same spot twice. Great blue herons are the largest North American herons. They appear blue-grey with a long yellow beak and long, thin, grey legs. In this region of the US, they can be found year-round.

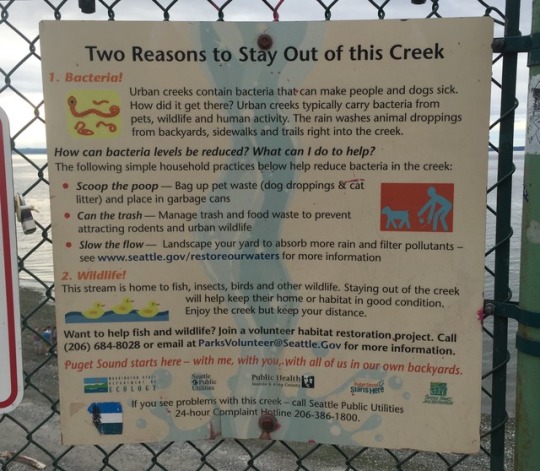

The creeks in Carkeek collect runoff from an urbanized watershed and are therefore polluted by pet waste, motor chemicals, and pesticides. It is not advised that you go in the water, but if you do, be sure to wash, especially before touching your face or eating. While humans are encouraged to stay out of the creeks, herons and salmon occupy the water. Salmon ceased spawning in Piper’s Creek after 1927 due to the poor water conditions. Various programs to repair the water quality led to the return of salmon in 1987, and salmon continue to return to spawn in these creeks today.

If you have not already reached spot 4 on the map, follow Piper’s Creek Trail around the Metro Plant, the building within the fence. Continue past this building to the bridge.

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great_Blue_Heron/id

http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20040815&slug=carkeek15

0 notes

Photo

Stop 5: Licorice Ferns and Mossy Maples

Once you’re between the creek and the small parking lot, take the first left onto Hillside Trail. When the trail forks, keep to the right to stay on the same trail. Soon, you’ll begin to see moss-covered big-leaf maple trees, Acer macrophyllum. These trees are coated in a variety of mosses, and out of these mosses grow licorice ferns, Polypodium glycyrrhiza. Unfortunately, the patch I managed to get a picture of was beginning to die, so there were only a few fronds and many were browning. These ferns are typically a vibrant green.

Licorice ferns are an epiphyte, which means they are a “plant that grows upon another plant or object merely for physical support,” according to Encyclopædia Britannica. They can be found on trees, fallen logs, and rock surfaces, for instance. Although not a parasite in any form, licorice ferns are dependent upon pre-existing structures for growth. So while the mossy tree cares not whether the fern grows, the fern cannot grow without the tree to hold it.

https://www.britannica.com/plant/epiphyte

0 notes

Photo

Stop 6: Plants

Continue along Hillside Trail. At the first fork, stay to the right. At the second, to the left. You will come upon two sections of stairs. Climb the first section to the small landing, then only to the 4th step of the second set. This is the location to which I returned almost weekly to document the changing landscape. Just behind you to the north (your right) is the ladyfern patch (Atherium filix-femina) I watched grow over the course of my observations. The ground-cover plant next to the ferns, with pointed, five-lobed leaves are Pacific water-leafs (Hydrophyllum tenuipes). If you turn around, the round-lobed ground-cover you’ll see on the other side of the trail are fringecups (Tellima grandiflora). Amidst the fringecups are taller stalks with three-lobed, pointed leaves. These are the large-leaved avens (Geum macrophyllum). Behind the fringecups and avens, you can see two large shrubs with three serrated leaves in clusters, and if you cover the distal leaf, the remaining two leaves look like butterfly wings. This shrub is salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis). If you turn around again, back to the side with the ladyfern patch, the large shrub behind the waterleafs, with the broad, soft, five-lobed leaves is a thimbleberry plant (Rubus parviflorus).

The most common tree you can see in this spot is the alder (Alnus sp.), but there are two western red cedars (Thuja plicata) and a big-leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum). Near the ladyfern patch is an Indian-plum (Oemleria sp.). For more information on the plants around you and how to identify them, please click the “Journal” link at the head of my blog.

0 notes

Photo

Stop 7: Song Sparrows

If you were listening while admiring plants in the previous spot, you might have heard this bird singing. Follow Hillside Trail a few metres further around the bend to a patch of less dense plants. Standing here puts you in a song sparrow’s territory. If it’s springtime, you might be able to hear a few sparrows defining their territorial limits. This spot unfortunately requires a bit more work than any other on this tour. In the pursuit of a better glimpse of this bird, I highly recommend pulling out a smartphone (how entitled of a tour, to make you bring your own equipment) and looking up a song sparrow song. The songs of these birds vary regionally. I prefer to use a call from Washington, Oregon, or California to lure out birds in the park, but other song sparrow dialects may also work. If you stand and play the call, ideally the territory owner will come circle you in an effort to find and scare off the intruder.

Song sparrows, and many other birds, are highly territorial in defense of the best resources. Birds sing to outline their territories, and males sing to lure a mate and to encourage other males to stay away. The song sparrow hears a call of a different bird in their territory, and they come to defend their resources. Song sparrows softly match the songs of intruders and vibrate their wings as warning signs for the intruder to leave. If an intruding bird is seen and has not left after a series of warning displays, the territory owner will attack the invading bird. Most frequently, aggression between two live birds does not last long enough for a fight.

0 notes

Photo

Stop 8: Slugs

Right before this stop, there is an important tree you should see. When the trail forks, stay to the right along Salmonberry Trail. A couple metres after the fork, there is a western hemlock, Tsuga heterophylla, tree with the base of the trunk almost 2m off the ground to the north (your right) of the trail. This hemlock grew out of the nurse stump of what I believe was either a Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) or western red cedar (Thuja plicata). The bark at this point has decomposed away, and I unfortunately cannot identify a tree from the rotting inner wood. The roots of the hemlock grew through where the stump used to be and are now strong enough to support the tree, even though the wood of the stump continues to dissolve away.

On to the actual stop. Not even 10m further along the trail, you will see essentially directly in front of you, a big-leaf maple shaped like a backwards number 4. I have dubbed this the Slug Tree. The straight trunk of this maple is still alive, while the trunk that juts out to the side before bending skyward is actually a decomposing snag. A very small tributary of the creek runs right past this heavily-shaded tree. The combination of moisture and low light creates the perfect environment for a variety of slugs, as well as other invertebrates. Around Slug Tree you can find both black (Arion ater) and banana (Ariolimax sp.) slugs. The back section, the trunk, of black slugs appears furrowed. Banana slugs have a ridge or a keel down this part of their bodies.

0 notes

Photo

Stop 9: Land-Use

Follow the trail to the meadow and walk across the field to the fence. You’ll see a trail leading north along the fence line. Follow the fence to the parking lots, then up the stairs or along the road to the field area. Feel free to sit in the grass, on a swing, or at a picnic table before you learn more about this spot.

As I alluded to in the introduction to this tour, the land on which Carkeek Park is currently located was used by the Duwamish peoples until settlers forced them to move. The last residents within Carkeek Park were the Piper Family who homesteaded along the ravine. They were relocated, not for the first time, after the land for the new park was bought off them in the late 1920s. In 1953, funds were authorized to construct and pave the loop road you just crossed, along with a caretaker’s residence and service building near the entrance (which you did not pass), the picnic areas and stove shelter near you, and the footbridge you’ll cross on the way to the final stop. The first major construction within the park occurred in 1949, when the Greenwood Sewer District won the deed, despite protests from the Park Department, to construct a sewage treatment plant within the park. This plant was taken over by Metro in 1954 and is still active today. This is the building you walked by between stops 3 and 4. According to the official historical record of Carkeek Park, “Access to and construction of feeder sewer lines into and through the park plus subsequent washouts by pipe breaks have changed the park from a ‘wilderness’ area into an ‘urbanized’ park.”

Though the park opened in its current location in 1928, the Park Department formally dedicated the new Carkeek Park on June 30, 1955.

http://clerk.seattle.gov/~F_archives/sherwood/Carkeek.pdf

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stop 10: Waterfront

If you turn back toward the water and look to your left, you should see a bridge. Cross that bridge and take the stairs down to the beach. Find a driftwood log and sit, facing the water. Take a deep breath in. Breathe out.

I chose Carkeek Park as my observation site primarily for its waterfront access. While my particular observation spot was not even along the creek, I valued the potential to come sit and look out over the water after documenting my site. This small waterfront, with its white, dried driftwood logs and tumbled rock beach, littered with crab exoskeletons and washed-up kelp and seaweed, has so much simplistic beauty.

If it’s a clear day, you can see the Olympic Mountains across the water. In front of the mountains, though, you can also see Bainbridge Island to the south (your left), with more of the Kitsap Peninsula if your gaze pans north (your right). The land far off to the north (still your right) is the southern coast of Whidbey Island. Along the coast, you may see various waterfowl, including mallard or gadwall ducks. I have once seen a heron wading near the shore. Crows sometimes come down to the waterfront, as well. Seasonally, baby harbor seals are reportedly found resting on the beach.

0 notes

Text

Final Words

Through my time at Carkeek Park, my view has shifted from the bigger picture of the forest to the intimate details of my environment. Surrounded at first by predominantly indiscriminate green, I watched a patch of ladyferns grow to full height while my eyes adjusted to the variety of species around me. Almost every week, I noticed new plants, fungi, or animals and learned to see the minute changes in height of specific plants or flower life cycles. While I tried to absorb the environment around me, the forest tried to absorb the trail back into wilderness. In order to observe for my final journal entry, I had to force my way through trail sections where plants on both sides of the trail were overgrown, touching or nearly touching in the middle. Although I felt this way before I began my observations, my time in Carkeek reinforced my reverence for the natural growth of forested environments and enhanced my perceptiveness for the diversity of species to be found in any environment. Despite the energy required to go out and document so much every week, I rather enjoyed the removal from urban environments Carkeek Park allowed, and I would agree that natural history is indeed innately pleasurable.

Before I took this course, the Puget Sound Region was an abstract space, with the Puget Sound being a sort of synecdoche for all lake-like bodies of water this side of the peninsula. I knew that both Lake Washington and Lake Union were relatively near UW campus, but I couldn’t remember which lake is which. I had no idea about the wide diversity of environments in the region: the different types of forests, the prairies, the wetlands. I had never been to the peninsula or seen a tide pool before this class. I had seen drumlins, but had no understanding, name, or explanation for their existence. I was not entirely oblivious; I understood that forests dominate the area between the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges, and there are a series of islands littering the water between the Olympic Peninsula and the rest of the state, but there was so much I had no idea I didn’t know.

The Puget Sound Region, I have learned, includes a variety of landscapes, each with a wealth of unique species. I’ve learned the lakes and many major rivers, including some that have been drained or straightened in the process of urbanizing the Seattle area. I understand the thousands of years of glaciation and tectonic activity that resulted in the unique topography of this region. I had the opportunity to visit more unique environments this quarter than I have had since moving to in Seattle. One of the reasons I moved to the Pacific Northwest is because the landscape here is absolutely beautiful. I have only fallen more in love with this region.

Observing the change in a landscape over time, noticing more than simply deciduous leaves falling or flowers blooming, but noticing change in height, flower number, or the emergence of a new species allows for the intimate knowing of a natural place. My extended time at Carkeek Park enabled the sea of green by which I was surrounded to become a menagerie of Pacific waterleafs, large-leaved avens, fringecups, lady and swordferns, Indian-plum, thimbleberry and salmonberry plants, and numerous trees. I have no doubt that if I return again to that location, I will notice even more species and will never be sure if they are new plantings or simply evaded my eyes previously. Though I currently know no other specific landscape that I know as well as my observation location at Carkeek, I’ve begun to be more intimately acquainted with the more general landscape across the Puget Sound Region. As I’ve said, the forests flanked by mountains have become a patchwork landscape of western hemlock or Sitka spruce dominated forests, prairies, wetlands, alpine and subalpine regions, and many others. The trips that allowed me to see these varying landscapes and unique species have widened my perspective on the variety of ecologies across the Puget Sound Region, but none as intensely and as minutely as my observation of Carkeek Park. The repeated and extended exposure to a specific location truly helped me attain a deep understanding of the specific details of the landscape and the species therein, a perspective I don’t think can be achieved through any other means.

I took this class with the intent of learning to identify plants of the region. My ultimate goal was to be able to, while hiking around this side of the Cascades, point out plants along the trail and identify which ones were edible. While it theoretically is easy enough to learn to identify plants on my own, I was uncomfortable with field guides and unsure of my ability to make correct identifications without a second opinion. This class gave me a starting point to plant identification, introducing me through in-the-field learning and working backwards with a known plant to the field guide description. This class easily exceeded my goals and also taught me ethnobotanical history and a variety of bird species. Now that I have had this class as a springboard, my interest in natural history and my curiosity about other species has only continued to grow. I have learned to identify plants and a few birds outside the scope of this class, as well as various species of slugs and a handful of fungi and lichens, kingdoms I was excited about before beginning this course. I feel encouraged to slow down outside and notice the minute details of the plants and animals around me. I’m inspired to continue learning about any environment in which I find myself.

To me, prior to this class, “natural history” included geomorphology and flora of the landscape. It never occurred to me that natural history should include animals, particularly birds, many of which are migratory and therefore not inherently bound to any one geographic locale. I never considered natural history something I would find fascinating or in which I would have a vested interest. I’m still, unfortunately, unsure about the specific relationship between human activity and natural history. At which point have humans altered an environment so much that it can no longer be called “natural”? How far removed from nature are humans that their activity should be delineated into a separate study? These questions and similar others seem to plague natural historians, so I shouldn’t feel too badly. However, I think it’s interesting that some acts of indigenous peoples are considered part of natural history while actions by, especially European, settlers are generally considered outside the scope. I find this vaguely dehumanizing, this separation of indigenous versus colonizing; I feel it reduces indigenous peoples to a more animalistic and primitive status than how colonizers are viewed. I’ll continue to work with my personal boundaries on my own time.

This class taught me to slow down, to be not only present in the environment, but to be present within the environment. I learned to notice species and their unique attributes and relationships to the ecology as a whole. I’ve become more invested in natural history after observing the changes in one landscape over the span of months and also after seeing the wide variety of ecologies across the Puget Sound Region. This class has only emboldened my reverence for natural landscapes.

0 notes