Photo

Photograph by Francis Miller. Mariemont, Ohio, 1950s.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

packed theater at the Cincinnati Zoo, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1941

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Students dancing at the Mariemont High School prom. Photograph by Francis Miller. Cincinnati, Ohio, May 1958.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lewis Wickes Hine, Cincinatti, Ohio, August 1908.

“134 Broadway, Cincinnati, Ohio. Harry McShane, 16 yrs. of age on June 29, 1908. Had his left arm pulled off near shoulder, and right leg broken through kneecap, by being caught on belt of a machine in Spring factory in May 1908. Had been working in factory more than 2 yrs. Was on his feet for first time after the accident, the day this photo was taken. No attention was paid by employers to the boy either at hospital or home according to statement of boy’s father. No compensation.”

Source: Library of Congress

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alfred T. Palmer, Aluminum paint production. Women work alongside of men in this Midwest aluminum factory now converted to production of war materials. These young workers are assembling 37mm armor-piercing shot prior to heat treating operations, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1942.

Source: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1905, Cincinnati Vainly Hoped To Double Its Population In Just Five Years

Talk about optimism! In 1905, the Cincinnati Post ran a contest looking for ideas on how Cincinnati could increase its population to 600,000 in time for the 1910 census, only five years hence.

Although Cincinnati was still a growing city – no census marked a decrease in our city’s population until 1960 – any notion that the population might top half a million, much less 600,000 was beyond ambitious. It was flat-out crazy. Still, the progressive Cincinnati Post [16 November 1905] persisted, announcing monetary prizes for the best ideas on how to achieve a population explosion in a few short years.

“If someone should start a 600,000 club in Cincinnati, it would become the biggest organization in the world. This is evident in the fact that every one in Cincinnati, and nearly every one in Southern Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky and West Virginia, would join it. Not only are the people of Cincinnati interested for the greater city, but those outside the city also.”

In the event that folks needed a little incentive beyond civic pride, the Post offered monetary rewards for the best ideas on how to increase the city’s population to 600,000 by 1910. First prize was $50, second prize was $25 and five third prizes of $5 rounded out the awards. From November 1905 into mid-January 1906, the Post published ideas as they arrived and interviewed city dignitaries about the ingenuity of the contest.

Among the celebrities interviewed about the initiative was Joseph B. Foraker, former governor of Ohio and current U.S. Senator from Ohio. He told the Post [15 November 1905]:

“Keep building skyscrapers. One can scarcely realize the great change that has come to the city. Why, from my window they are jumping up until the city is looking like an oil field. They are filled, too, just as rapidly as they are built. Make room for the people, and they will come along.”

Compared to some of the other ideas submitted to the Post, Senator Foraker’s suggestion was rather tame.

J. Louis Bunn, a house painter, suggested rerouting the Ohio River from Coney Island to Sedamsville southward into Kentucky, so that Covington, Newport, Bellevue and Dayton would be transplanted to Ohio and therefore become part of Cincinnati.

Frank Boies, a shoe-cutter, was convinced that closing all saloons on Sunday would do the trick.

Harry Dilg, an express delivery driver, lobbied for more championship prize fights being hosted by Cincinnati.

A contestant who signed his entry “Stranger” made a list of obstacles to Cincinnati’s growth. Would Cincinnati ever achieve 600,000 population? According to “Stranger”:

“Not as long as the Traction Company is not compelled to give the people better service. Not as long as the sweeping of any old rubbish, especially paper, off the sidewalk and into the street is allowed. Not as long as property-owners or their agents are indifferent to the appearance of property that has become vacant. Not as long as corporations are not compelled to think of others as well as themselves. The worst case of this kind will be found in the so-called ‘waiting room’ at the foot of Art Hill, sometimes called the Lock-st. Incline. W. Kesley Schoepf [president of the Traction Company] would not think of using it as a garage for his automobile, yet he expects patrons to ‘wait’ in there until one of his 5-cent carriages that you are compelled to stand up in half the time comes along.”

No newspaper contest, of course, would be complete without an entry from an adorable schoolgirl. The Post [28 December 1905] prominently blazoned the ideas of 13-year-old Gladys Schultz of Linwood, who wrote her contribution in verse:

“Annex all the villages in Hamilton County;

Give all small manufactories a bounty.

Exempt from taxation all chattels;

Help the businessman fight some of his battles.

Tax real estate all it will stand –

The banker can lend a helping hand.

Fill the Mill Creek Valley above high-water mark.

Build factories thereon with space for a park.

An underground railway, with a boulevard top,

Our unsightly canal will make a beautiful spot.

A union depot for all railroads to come in,

Will bring 600,000 by 1910!”

The Post encouraged contestants to submit multiple entries and John Miller, a harness maker, complied by compiling 36 ideas into a single entry. Mr. Miller [11 December 1905] covered quite a bit of territory with his suggestions, ranging from the mundane . . .

“22. For Cincinnati to send a letter of thanks to President Roosevelt and Secretary Taft for the good they did in the last election.”

. . . to the idealistic.:

“36. Abolish capital punishment.”

Along the way, Mr. Miller lobbied for more monuments, an eight-hour work day, honest elections, free schoolbooks in the public schools, more parks along the riverfront and better service at the city hospital.

The winner of the big $50 prize was Marion L. Pernice Jr., assistant advertising manager of the Fay & Egan Company, manufacturers of woodworking machinery. His suggestion boiled down to essentially one word: Advertise! Pernice suggested that all goods manufactured in Cincinnati be labeled “From Cincinnati” and that only goods manufactured in Cincinnati be eligible for that slogan. All suburban manufacturers would lobby for annexation to Cincinnati to carry that prestigious mark.

Alas, the contest did not achieve its stated goal. Cincinnati’s population in 1905, approximately 340,000, reached only 364,000 in 1910. Evan worse, the census of 1910 marked the first time since 1830 that Cincinnati was not ranked among the largest 10 cities in the United States. It would be 1950 before Cincinnati achieved 500,000 residents and 60 years of population decline followed until an uptick in the 2020 census.

And yet, no serious discussion about re-channeling the Ohio River.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Selecções do Reader’s Digest, Nº 82, November 1948.

The Crosley 58 XA Radio is unrivaled. Completely new… in design and functions. Totally climatized.

The new, great Crosley 58 XA, climatized to endure extreme heat and humidity, has a splendid reception that you’ll enjoy for many years to come.

Its outer case is in sumptuous black and red plastic. Extra-robust for a clear reception and a fine synchronizing in three bands of world wide reach. Works on alternated current from 50/60 cycles to 105-130 volts or 50/60 cycles to 210-260 volts.“

9 notes

·

View notes

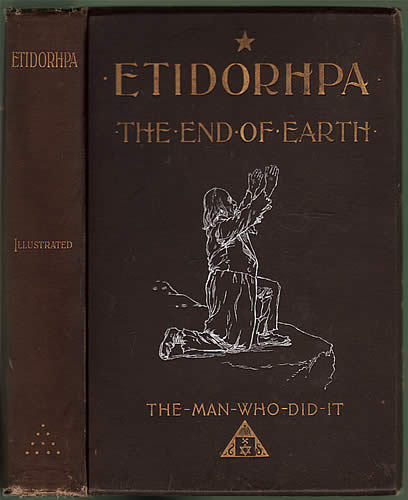

Photo

Etidorhpa or the End of Earth, Signed Limited 1st Edition. by John Uri Lloyd.

Cincinnati: John Uri Lloyd 1895. Octavo 18 x 26.5 cm 376pp. Limited first edition signed by the author at the end of a two-page (printed) letter prior to the title page as issued. Original brown cloth over bevelled boards decorated in silver and gilt. Portrait frontispiece; illustrations by J. Augustus Knapp. via Powell’s Rare Books

I had to dig around and ended up at Wikipedia to find out what this book actually contains. From wiki: “The book purports to be a manuscript dictated by a strange being named I-Am-The-Man to a man named Llewyllyn Drury. Drury’s adventure culminates in a trek through a cave in Kentucky into the core of the earth. Ideas presented in Etidorhpa include practical Alchemy, secret Masonic orders, the Hollow Earth theory and the concept of transcending the physical realm.”.

9 notes

·

View notes

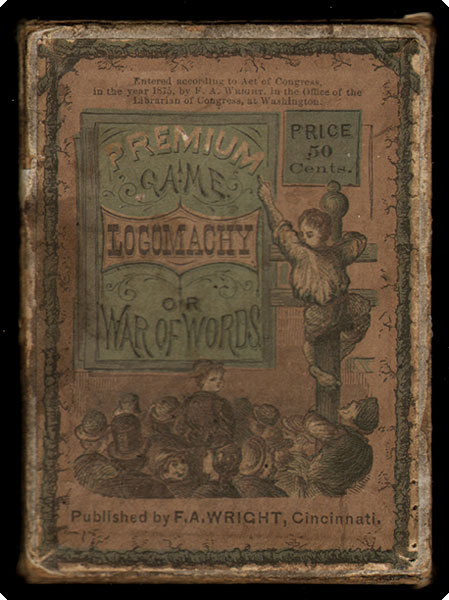

Photo

Logomachy or War of Words

F. A. Wright. Cincinnati: 1875.

Very early appearance of one of the most popular 19th-century parlor games published in the United States: a set of 56 illustrated, black-and-white cards with a folded, four-page leaflet of rules for the word game Logomachy, which first appeared in 1874 (the date given on the rulebook here) and won a silver medal at that year’s Cincinnati Industrial Exposition. “Logomachy” means an argument about words, and the point of this word-making game is to make the best use possible of the available letters in one’s hand and on the table before opponents get a chance to steal the word in play; this is like Scrabble and NOT.

B-A Note: I’m very sorry that this was sold before I even knew of it!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1872, Cincinnati Ground To A Halt As The City’s Horses Succumbed To A Virus

It sounds like something out of a science fiction movie. For nearly three weeks in the autumn of 1872, Cincinnati was paralyzed by a virus with no known cure.

Humans were not susceptible to this virus. It only affected horses, but the entire operation of Cincinnati life and business depended primarily on horses. When the city’s horses were incapacitated, Cincinnati screeched into paralysis.

The strange episode began one evening in October when Dan Rice’s circus rolled into town. Four of the horses showed symptoms of some sort of respiratory illness and were taken to veterinarian George W. Bowler for treatment. Dr. Bowler readily identified the affliction as the “Canadian horse disease” that was then infesting the northern tier of states but doubted it would spread beyond his stable on Ninth Street.

Alas, Dr. Bowler’s optimism was unfounded and the next few days found cases throughout the downtown area. Journalists struggled to name the disease. “Epizooty” was a common label, but newspaper reports invoked “equine influenza” or “hippo-typhoid-laryngitis” or “epiglottic catarrh” or “epizootic influenza” and even “hipporhinorrheaeirthus”! Whatever they called it, the disease would hobble a city absolutely dependent on horse power to operate at all.

Josiah “Si” Keck, presiding at the Board of Aldermen, introduced a resolution to draft squads of men for duty at the city’s firehouses. With the horses out of commission, only manpower could replace horsepower to haul the heavy steam-powered fire engines of the day. Thankfully, only a few minor fires were reported during the height of the contagion.

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer [11 November 1872], other horse-dependent companies tried different alternatives:

“The United States Express Company has prepared to follow the example of the Eastern Companies. All of their horses, twenty-two in number, being completely disabled, they will at once substitute steers, and the streets of this city will show the curious spectacle of express wagons drawn by the propelling force of a farmer’s haycart.”

Historian Alvin F. Harlow, writing in the Bulletin of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio [April 1951], noted that the bovine substitutes were simply not cut out for jobs readily accomplished by horses:

“The oxen, with great, wild, pathetic eyes, slobbering, swaying slowly through the streets, were a strange spectacle to city folk, and were followed by crowds of children for a day or two, until the novelty wore off. But as agencies of traction, they were a disappointment. Not all of them were well broken to the yoke; few men in town knew how to drive them, and as they are—with the possible exception of the tortoise and the two-toed sloth—the slowest walkers in the whole zoological category, they did not accomplish much in a day, according to city standards.”

Just think of an entire city operating on the capable talents of horses, now immobilized by an unseen microbe. Garbage piled up as the city’s sanitation wagons stood idle. “Garbage” back then meant kitchen and table scraps which, even in the chill of autumn, ripened malodorously in unattended cans. The situation was even worse at the city’s slaughterhouses. Even though the butchers had stopped working – there were no wagons available to deliver the slaughtered pork and beef – there were likewise no wagons to dispose of the offal and trimmings. The stench was indescribable.

Cincinnati’s streetcars were horsedrawn in 1872. It would be a decade before electrical trolleys debuted. The entire commuter system of the city shut down and the Cincinnati workforce, from C-suite executives to the lowliest laborers, had to hoof it. Harlow describes an exhausting scene:

“Towards dusk each evening the great trek homeward began, and from then until 9 P.M. the streets were thronged with business men, clerks, bookkeepers, warehouse and factory workers, trudging wearily. To reach their work again at 7 or 7:30 next morning, when most people's day began, soon proved too much for some of them, and they took to sleeping in their places of business; which in turn became less and less necessary, as those businesses were compelled to shut down for lack of transportation.”

Even funerals were affected. Teams of undertakers pulled hearses to the depot of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton railroad, whose tracks ran along the front of Spring Grove Cemetery. Mourners followed along on foot until the hearse was loaded on the train, then rode out for the burial. Other cemeteries put interments on hold for the duration.

The city faced the serious prospect of starvation. Food arrived in the city by rail and by river, but there were no carts to carry it from the wharf or the depot. Fresh vegetables rotted down by the river while families went hungry just a few blocks north. Farmers from the suburbs refused to bring their crops into Cincinnati for fear that their own draft animals would succumb to the dread epizooty.

As humans attempted to fill the horse’s role, every wheelbarrow in the city was drafted into use and some sold for astronomical sums. Even so, as noted by Harlow, human power had its very fragile limits:

“If the load was very heavy, as for instance, hogsheads of tobacco, massive machinery or an iron safe of a ton weight, ropes were also attached to each side of the wagon and passed over the shoulders of two files of straining men, while three or four others, their feet striving for toeholds in earth or cobbles, pushed against the wagon's tail until shoulder-bones threatened to wear through the flesh.”

Among the worst effects of the pandemic was the inability to dispose of dead horses. Horses died in Cincinnati at the rate of twenty or thirty a day at the height of the disease in November 1872, and there was nothing available to haul the carcasses out to the reduction plants, where they might be turned into soap fat or fertilizer. Alderman Si Keck, who owned one of these “stink factories,” found a partial solution by renting a small steam-powered truck from one of the city’s pork-packing plants but could still handle only a few of the equine corpses.

By the end of November, new cases and fatalities had diminished considerably. As December opened, the city was almost back to normal, with a new appreciation of the four-legged residents who truly powered our city.

Only one case of a human contracting the epizooty was recorded in 1872. Joseph Einstein was a well-known dealer when Cincinnati’s Fifth Street was the largest horse market in the United States. Einstein spent weeks, around the clock, nursing his stock and developed symptoms remarkably similar to those afflicting his horses. Several local doctors confirmed that he had somehow succumbed to the dread epizooty.

Just as mysteriously as it appeared, the epizooty vanished, and never visited Cincinnati to that degree ever again.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Wolverines with Beiderbecke at Doyle’s Academy of Music in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1924.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

United States Playing Card Co, 1952

211 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cincinnati Music Hall, designed by Samuel Hannaford in High Victorian Gothic style, and completed in 1878. The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Cincinnati Opera, May Festival Chorus, Cincinnati Ballet, and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra perform here.

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Postcard for the Nimrod Tent trailer, which retailed for $639

Cincinnati, Ohio 1961

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

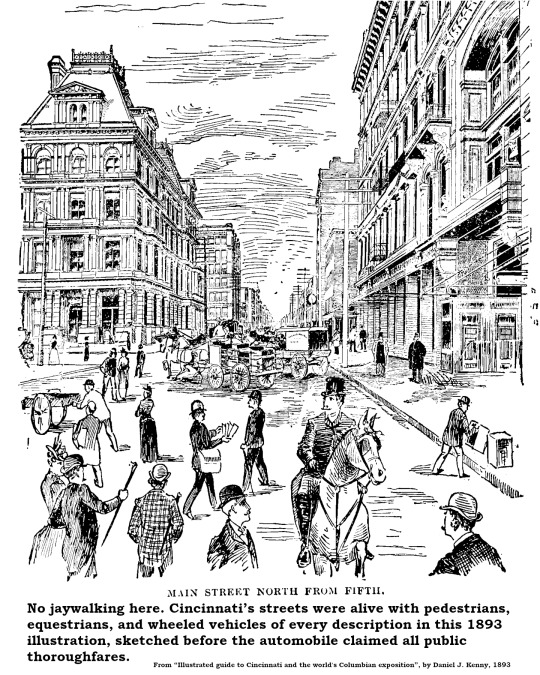

Cincinnati Surrendered To The Automobile When Jaywalking Was Outlawed

How many Cincinnatians subscribed to Popular Mechanics magazine in 1912? And how many of those subscribers recognized, in the September issue, a tiny article on Page 414 that laid out the future of the Queen City? It all seemed so innocent:

“The city pedestrian who cares not for traffic regulations at street corners, but strays all over the street, crossing in the middle of the block, or attempting to save time by choosing a diagonal route across a street intersection instead of adhering to the regular crossing, is designated as a ‘jay walker’ in Kansas City. Kansas City recently adopted a new ordinance for the control of foot traffic as well as vehicles, and ‘jay walking’ is to be prevented as rigidly as ‘jay driving.’”

That squib appeared adjacent to another brief item on how the brand-new town of Speedway, Indiana allowed only motorized vehicles on its streets, banning anything pulled by horses. In combination, the two articles sounded the death knell for a way of life that had existed for millennia.

Look at the illustrations that grace the old books about Cincinnati. There is no such thing as jaywalking. The streets were owned and enjoyed by the people. Pedestrians share the road with wheeled vehicles, crossing wherever convenient, even stopping in the middle of the street to chat. Horse-drawn carriages and wagons hauled passengers and freight. Men pulling handcarts and pushing wheelbarrows dodge the throng. The only motorized vehicles were the electric street cars, and they were confined to their tracks.

During election season, Cincinnati’s streets filled with torchlit political parades. On at least one occasion, a parade filled Vine Street from Fourth Street to McMicken with chanting men waving flaming brands, lighting the clouds above with a rosy glow. When any dignitary showed up in town, they were expected to speechify from their hotel balcony and people thronged the street below, halting traffic as they cheered. People crossing the street from any direction weren’t “jay walking.” They were just “walking.” The automobile changed all that.

Horse-drawn vehicles and electric streetcars killed a fair number of people, but the motor car quickly notched more than a hundred fatalities and many more injuries every year. Local media often blamed the victims. The Cincinnati Post [8 January 1916] piled on:

“Fourth-st. is the mecca of Cincinnati’s jay walkers. Most of the jay-walking is done between Vine and Race-sts. The other day we counted 20 persons crossing the street at different points at one time – and none was using a cross-walk. Fortunately accidents are rare on this street because of the extreme care exercised by autoists.”

It appears not to have occurred to the writer that this behavior, just five years previous, would have been considered normal.

The hammer landed in 1917. Cincinnati joined the ranks of other auto-infested cities that criminalized jaywalking. The new law went into effect in May of that year, restricting automobiles to no more than 8 miles per hour in the business district and 15 miles per hour in residential districts. For the first time, pedestrians were restricted to sidewalks and crosswalks. Pedestrians – literally – fought the new law. According to the Post [23 May 1917]:

“Theodore Mitchell, 38, agent, 631 Maple-av, is the first person to be arrested on a charge of jay-walking since the new traffic ordinance went into effect. Traffic Patrolman [Edward] Schraffenberger charged Mitchell attempting to make a short cut at Fifth and Walnut streets. When reminded of his mistake, Mitchell became angry, Schraffenberger said. Mitchell, charged with disorderly conduct and violating the traffic ordinance, was cited to appear in court Thursday.”

If you’d asked the cops, however, they would unanimously aver that the chief violators were women. The Post [21 May 1917] quoted Police Lieutenant Charles Wolsefer:

“The women are awful. They just don’t pay any attention at all. Just take a look at them crossing on Race-st.”

The reporter did so, and counted 48 jaywalkers, of whom 37 were women. A few days later, another Post reporter followed another policeman on patrol who confronted 25 jaywalkers, of which only two were men.

Among the first arrested was Miss Ella Bright of 538 Howell Avenue, Clifton, a teacher at Woodward High School. Miss Bright did not care for the attitude of the city policeman who accosted her. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer [7 June 1917]:

“She declared she had been upbraided unduly by an officer because she crossed the street in a manner which was a violation of the traffic laws after alighting from a street car.”

In August of that year, Mrs. John Mongan, 4217 Glenway Avenue, Price Hill, was arrested for striking a police officer who grabbed her arm as she executed a “Dutch Cut” (diagonal jaywalking) across the intersection at Sixth & Race.

Former U.S. President William Howard Taft, then on the law faculty at Yale, was visiting his hometown that year and blithely jogged across Sixth Street near Main, only to be corralled by Officer Joseph Schindler, who gave the law professor a little legal lesson.

The Post even enlisted its “boy reporter,” 12-year-old Freddy Printz, to test the city’s ability to enforce the new jaywalking regulations. On 7 July 1917, Freddy reported his fruitless attempts to get bawled out by a police officer. Despite blatantly jaywalking at five different locations, he only earned a polite reprimand from one officer.

While the local constabulary was doing their best to enforce the new laws, the automobiles were merciless. On 21 May 1918, the Post reported on the 25th traffic fatality of the year. The victim, a 12-year-old girl, was the twelfth child killed by an automobile that year.

Curiously, although Cincinnati outlawed jaywalking, the city had omitted one very important detail that might have contributed to compliance with the new law. A letter signed only “Chicagoan” appeared in the Post on 13 June 1917. The writer suggested that, like other cities attempting to get pedestrians to cross at intersections, Cincinnati should assist pedestrians by painting white lines on the street to mark approved pedestrian crossing paths. Cincinnati’s mandatory crosswalks were unmarked!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Martha, The World’s Last Passenger Pigeon, Photographed in Captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo Shortly Before Her Death and With it, The Extinction of Her Species 1914

Ave atque Vale

37 notes

·

View notes

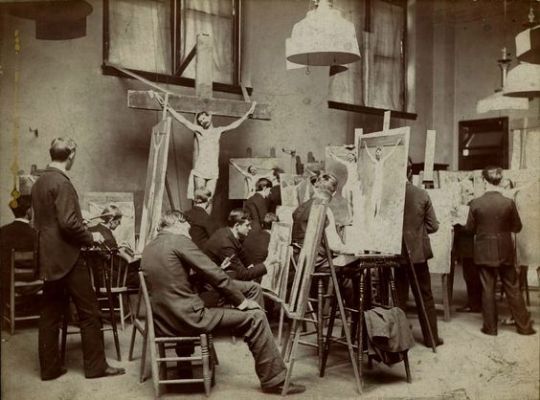

Text

Worst Job Ever!

Artist's Model at Art Academy of Cincinnati, 1900

41 notes

·

View notes