Text

Never did I feel, my dear Bonstetten, to what a tedious length the few short moments of our life may be extended by impatience and expectation, till you had left me [...] I did not conceive till now (I own) what it was to lose you, nor felt the solitude and insipidity of my own condition, before I possess'd the happiness of your friendship.

Thomas Gray to Charles Victor de Bonstetten, [12 April 1770]

~

Cold in my professions, warm in my friendships, I wish, my Dear Laurens, it might be in my power, by action rather than words, to convince you that I love you. I shall only tell you that ’till you bade us Adieu, I hardly knew the value you had taught my heart to set upon you.

Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, [April 1779]

#john laurens#historical john laurens#alexander hamilton#historical alexander hamilton#historical lams#thomas gray#karl viktor de bonstetten#queer history#18th century history

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

At length, my dear Sr, we have lost our poor de B:n [...] & here am I again to pass my solitary evenings, wch hung much lighter on my hands, before I knew him. this is your fault! pray let the next you send me, be halt & blind, dull, unapprehensive & wrong-headed. for this (as Lady Constance says) Was never such a gracious Creature born!

Thomas Gray to Norton Nicholls, 4 April 1770

[Bonstetten] gives me too much pleasure, & at least an equal share of inquietude. you do not understand him so well as I do, but I leave my meaning imperfect, till we meet. I have never met with so extraordinary a Person. God bless him! I am unable to talk to you about any thing else, I think.

Thomas Gray to Norton Nicholls, 20 March 1770

Gray, who was in Thomas Walpole's circle and thought by scholars to have been queer himself, was clearly captivated by Charles Victor de Bonstetten. The allusion to "pleasure" and "inquietude", and the hint of a deeper meaning to understand that can only be shared in person, seems to substantiate that there was an other-than-platonic attachment here.

#karl viktor de bonstetten#thomas gray#queer history#18th century correspondence#talk about being down bad

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Bonstetten] gives me too much pleasure, & at least an equal share of inquietude. you do not understand him so well as I do, but I leave my meaning imperfect, till we meet. I have never met with so extraordinary a Person. God bless him! I am unable to talk to you about any thing else, I think.

Thomas Gray to Norton Nicholls, 20 March 1770

Gray, who was in Thomas Walpole's circle and thought by scholars to have been queer himself, was clearly captivated by Charles Victor de Bonstetten. The allusion to "pleasure" and "inquietude", and the hint of a deeper meaning to understand that can only be shared in person, seems to substantiate that there was an other-than-platonic attachment here.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martha Manning Laurens and the "Lisle business"

You perhaps have heard that I have made a connection in the family of Mr Manning, a West India merchant; & that Col Laurens also made a like connection, (now ended by the death of Mrs Laurens.) [...]

Another opportunity, of a smaller kind offers, for your rendering civilities to the family of Mr Laurens. Mrs Laurens, wife to the Col., lately died at Lisle. The effects she left are few & trifling, but the [magis]trates of the place refuse hitherto to suffer the operation of her will, till the Cols. pleasure is known. Her clothes she bequeathed to her maid, to the amount only of some £20 or £30; & her watch & trinkets to a most lovely child [Frances], now in part an object of my cares. These are not matters worth the procuring a power of attorney or the like, from America, in order to settle, and the maid is now detained in Flanders looking after them. A Mr. Cowly a Superior of a convent there, and a Mr De Ronquet, have been written to; and Mr Laurens & Mr Manning, the father & father in law have but one & the same wish on the subject.

Benjamin Vaughan to Benjamin Franklin, November 1781

I have no Acquaintance at Lisle. If you will point out to me in what manner I can be useful, I will endeavour it: But I suppose the Gentlemen you mention will effectuate that small Affair.

Benjamin Franklin to Benjamin Vaughan, 22 November 1781

As to the Lisle business, you may recollect perhaps that I spoke of interference with the magistracy there. At all events, such a trifle was only meant for you to take part in, if you pleased, to shew the Laurens family attention_ I believe the business was settled by the persons I named; but I fancy the poor servant may have been lost in the pacquet—in which your letter was not included;

Benjamin Vaughan to Benjamin Franklin, 3 January 1782

Vaughan was the brother-in-law to Martha Manning Laurens – the connection he refers to is his marriage to her sister, Sarah – and the uncle of Frances Laurens.

#john laurens#historical john laurens#martha manning laurens#benjamin franklin#benjamin vaughan#frances laurens#18th century history

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Continentalist" – a linguistic puzzle

nothing but the approaching critical junction of southern affairs and the expectation of my countrymen could induce me to sollicit a farther leave of absence in case of my exchange_ I profess myself too much a continentalist to be affected by local interests_ but I indulge a hope that my acquaintance with the country [South Carolina] and connexions as a southern man may enable me to be of some ability in the new theatre of the war_

John Laurens to George Washington, 6 November 1780

In this letter, Laurens – currently on parole in Philadelphia as a prisoner of war – is asking Washington preemptively for permission to join the military campaign in the south.

What's interesting to me is the word "continentalist", which he is using to distinguish himself from someone whose interests are focused on their native state. Laurens is making the point that his allegiance is to the new union of states as a whole, and not just his 'country'. It's like someone today calling themselves pan-European instead of German or French.

The way Laurens uses it suggests that it's a familiar enough word, but the only other related instance that I have found is from the title of Alexander Hamilton's essay series, The Continentalist (published from July 1781). And indeed, the Oxford English Dictionary states, "OED's earliest evidence for continentalist is from 1781, in the writing of Alexander Hamilton".

Searching for this term on Founders gives Laurens's usage as the first instance, and Library of Congress doesn't bring up anything earlier either. It's not included in Samuel Johnson's dictionary, or several other sources I've skimmed.

So now I'm interested to find out where "continentalist" came from. Was this a word coined among Washington's staff to describe their broader perspective on the revolution? If anyone has any other leads or sources, please do share.

#john laurens#historical john laurens#alexander hamilton#george washington#18th century history#amrev#this also adds a strong argument for laurens being a federalist

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

@icarusbetide this man was a menace.

I must beg the favor of you to send by the earliest opportunity a copy of the last Resolves of Congress relative to the exchange of Prisoners, the 21st Ulto. It has been mislaid here_ and the person who had the care of it, wishes to avoid the pain wound to his sensibility which wd arise from having the matter applied for officially with an explanation_

John Laurens to Henry Laurens, 7 June 1778

Mmm. Okay.

...it was Hamilton, right?

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

We shall meet again – we shall live to look back upon all that has happen’d as upon a troubled dream, & your face will be as easy to shave as ever

Francis Kinloch to Johannes von Müller, 4 September 1803

Kinloch writes this reassuring line to his dear friend Müller in the wake of a heartbreaking scandal; Müller had recently suffered almost total financial ruin (not to mention shame and legal peril) as a result of responding to faked homoerotic love letters from a fictional Hungarian count.

This sentiment is really tender and touching for two reasons. First, it’s plain that Kinloch isn’t bothered at all by the scandal or Müller’s having been outed as homosexual (almost certainly because he was well aware of this from his own first-hand experiences in the 1770s). He even makes a point of emphasising his continuing “sincere and unalterable friendship” for Müller.

Second, Kinloch must have heard (or intuited) that the stress of the situation had robbed Müller of his famously round and soft baby-face. So, he reassures Müller that he will recover his wellness soon enough - making his now-haggard and angular face “easy to shave” again.

#the implied domesticity here is 11/10#absolutely convinced that there was mutual shaving going on in chambesy#francis kinloch#johannes von müller#18th century history#queer history

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨Speculation time!✨

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Play along: Amrev codebreaker!

While browsing through some primary materials reading up about John Laurens’ mission to France as special minister to the court of Versailles, I came across a letter that he wrote to the president of the Continental Congress on 9 April 1871 that included a coded message using a numerical cipher.

I took a shot at deciphering it – here’s the process I followed, and you can play along too!

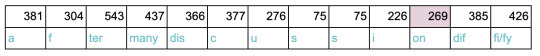

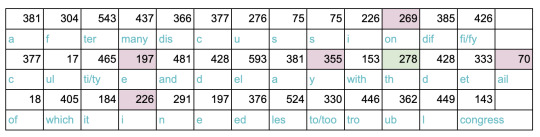

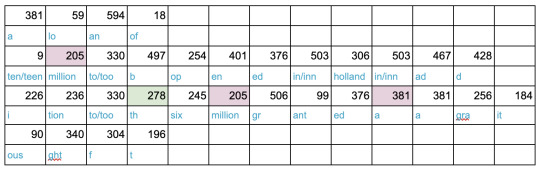

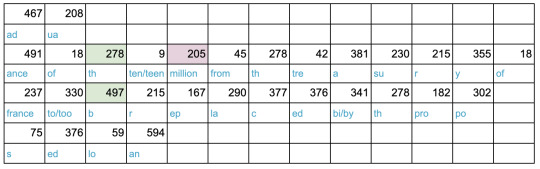

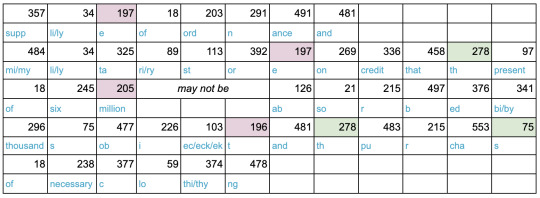

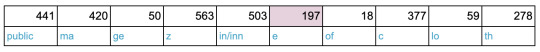

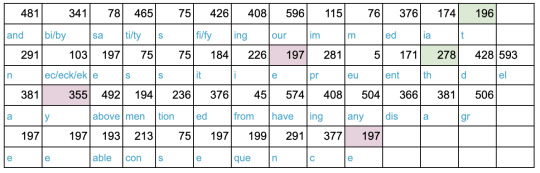

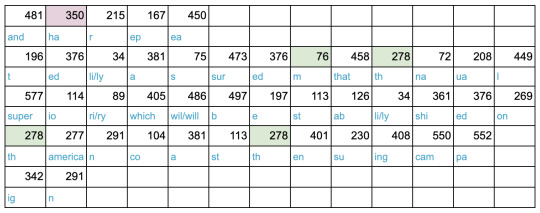

1. The first step, of course, was to determine which specific encryption was being used. After a bit of digging, I came across the immensely useful United States diplomatic codes and ciphers, 1775-1938 by Ralph E Weber. He explains that the cipher in question was “prepared on separate encode and decode sheets, the latter contained 660 printed numbers, with usually 600 words, syllables, and letters of the alphabet scattered randomly throughout the sheet.” So, for example, the word “congress” is “143”, the syllable “el” is “593” and the letter “r” is “215”. This cipher was an updated and improved version of the one used by Benjamin Tallmadge, and Weber explains that Laurens was the first one to use it. Weber also handily provides the decode table in an appendix.

2. The second step was to design an efficient way to decode the hundreds of numbers Laurens used in his letter, and the obvious answer was my good friend the spreadsheet. I transferred the table from the book to Google Sheets, which was mildly tedious but hugely time-saving later on.

3. Now the fun part! I typed out the numbers from Laurens’ letter, and then used a simple LOOKUP formula to match the number to the decoded text.

The cipher also includes two nuances - an underscore beneath the word means a plural, and an overscore denotes adding an “e” - so I marked these in the cells with pink and green highlights respectively.

4. The final step was correcting a few errors in my table, refining the decoding (some numbers have various iterations to save space, such as 103 which can be any one of “ec/eck/ek” depending on which syllable is needed), and extracting the final text.

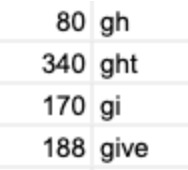

It all reads very smoothly, with the singular exception of “ght-f-t”, which is the way Laurens rendered the word “gift”. The obvious explanation for this mangle is that he mis-wrote 340 (ght) instead of 170 (gi).

That’s definitely 340, 304, 196 which decodes as “ght-f-t”.

While it seems like a strange error to make, bear in mind that the encoding sheet (the one Laurens was using to change plaintext into numbers) would have been listed in alphabetical order to make finding the numbers easier (while the person at the other end has the sheet in numerical order, to reverse the process just as easily). And when we sort alphabetically, we can see that 340 and 170 are right next to each other:

A simple slip to make for someone writing coded letters late at night in low candlelight.

If you want to play along:

Here’s the code/decode spreadsheet.

And here is the transcribed text (underlines for plurals, asterisk for added “e”). I've given the solution under the cut!

I have employed the most unremitting efforts to obtain a prompt and favorable decision relative to the object of my mission_ 381, 304, 543, 437, 366, 377, 276, 75, 75, 226, 269, 385, 426, 377, 17, 465, 197, 481, 428, 593, 381, 355, 153, 278*, 428, 333, 70, 18, 405, 184, 226, 291, 197, 376, 524, 330, 446, 362, 449, 143

The Count de Vergennes communicated to me yesterday his most Christian Majesty's determination to guarantee 381, 59, 594, 18, 9, 205, 330, 497, 254, 401, 376, 503, 306, 503, 467, 428, 226, 236, 330, 278*, 245, 205, 506, 99, 376, 381, 381, 256, 184, 90, 340, 304, 196

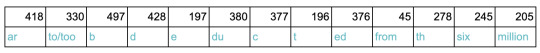

...and the value of the military effects which may be furnished from the Royal Arsenal, 418, 330, 497, 428, 197, 380, 377, 196, 376, 45, 278, 245, 205

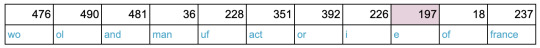

I shall use my utmost endeavours to procure an immediate 467, 208, 491, 18, 278*, 9, 205, 45, 278, 42, 381, 230, 215, 355, 18, 237, 330, 497*, 215, 167, 290, 377, 376, 341, 278, 182, 302, 75, 376, 59, 594, and shall renew my solicitations for the 357, 34, 197, 18, 203, 291, 491, 481, 484, 34, 325, 89, 113, 392, 197, 269, 336, 458, 278*, 97, 18, 245, 205 may not be 126, 21, 215, 497, 376, 341, 296, 75, 477, 226, 103, 196, 481, 278*, 483, 215, 553, 75*, 18, 238, 377, 59, 374, 478, the providing this article I fear will be attended with great difficulties and delays as all the 476, 490, 481, 36, 228, 351, 392, 226, 197, 18, 237, are remote from the sea, and there are no 441, 420, 50, 563, 503, 197, 18, 377, 59, 278, suitable to our purposes.

The cargo of the Marquis de la Fayette will I hope arrive safe under the convoy of the Alliance_ 481, 341, 78, 465, 75, 426, 408, 596, 115, 76, 376, 174, 196*, 291, 103, 197, 75, 75, 184, 226, 197, 281, 5, 171, 278*, 428, 593, 381, 355, 492, 194, 236, 376, 45, 574, 408, 504, 366, 381, 506, 197, 197, 193, 213, 75, 197, 199, 291, 377, 197

The Marquis de Castries has engaged to make immediate arrangements for the safe transportation of the pecuniary and the other succours destined for the United States_ 481, 350, 215, 167, 450, 196, 376, 34, 381, 75, 473, 376, 76*, 458, 278*, 72, 208, 449, 577, 114, 89, 405, 486, 497, 197, 113, 126, 34, 361, 376, 269, 278*, 277, 291, 104, 381, 113, 278*, 401, 230, 408, 550, 552, 342, 291

Have fun!

I have employed the most unremitting efforts to obtain a prompt and favorable decision relative to the object of my mission_ after many discussions, difficulties and delays with the details of which it is needless to trouble congress.

The Count de Vergennes communicated to me yesterday his most Christian Majesty's determination to guarantee a loan of ten millions to be opened in Holland in addition to the six millions granted as a gracious gift.

...and the value of the military effects which may be furnished from the Royal Arsenal are to be deducted from the six million.

I shall use my utmost endeavours to procure an immediate advance of the ten millions from the treasury of France to be replaced by the proposed loan,

and shall renew my solicitations for the supplies of the ordinance and military stores on credit that the present of six millions may not be absorbed by thousands objects and the purchase of necessary clothing

the providing this article I fear will be attended with great difficulties and delays as all the wool and manufactories of France are remote from the sea, and there are no

public magazines of cloth suitable to our purposes.

The cargo of the Marquis de la Fayette will I hope arrive safe under the convoy of the Alliance_ and by satisfying our immediate necessities prevent the delays above-mentioned from having any disagreeable consequences

The Marquis de Castries has engaged to make immediate arrangements for the safe transportation of the pecuniary and the other succours destined for the United States_ and has repeatedly assured me that the naval superiority which will be established on the American coast the ensuing campaign

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francis Kinloch in Müller's letters to his family: Part 4

These extracts are from Johannes von Müller: Sämmtliche Werke, volume 7 (1810).

My translations here (with added paragraph breaks for legibility), original German transcriptions below the cut. This is the queerest part yet.

29 July 1776, to his father

The first cause of my silence, l. P.,* is that my regulated life really leaves me with little to write about; the other: that I am very busy. I read for a few hours with my friend, and that is almost the only time that I can devote to reading.

*For “lieber Papa”, “dear father”.

10 Oct 1776, to his father

You can guess the reason for my long silence, dearest father; when one is labouring on an important work, one becomes this work entirely; and in addition I finished a few more books with my friend Kinloch.

[...] A book seller from Neuchatel, Mrs B and I have convinced Mr B to put together a collection of his works. On account of this opportunity, he is working through all of them, and making additions and changes. Since he is not allowed to read himself, he wished to go through these writings with a friend who was already familiar with the contents. To that end, this summer we often read these and other writings for 2 – 3 hours a night in Mr Kinloch’s presence.

[...] My friend K is going to Italy. It is difficult; but the North American war and my work, which would be too disrupted, prevent me from accompanying him. This letter is not long enough to express to you how painful parting from him the day after tomorrow* will be for me.

[...] The loss of my friend makes me sad. Luckily, Kinloch is mine in every part of the world; our persons may be separated, but not our minds; I should care more about his perfection than about his presence; one day, in the long career that according to nature is open to us, we may well find ourselves together again**

*This places Kinloch’s departure for Italy on 12 October 1776.

**Original annotation: This friendship with Mr Kinloch remained unabated until Müller’s death. He received letters from him even in Cassel.

24 Dec 1776, to his brother

For myself, I seek nothing except that independence, which I consider to be the highest good of a human being, which I now enjoy, and will always enjoy through the generosity of my friend Kinloch and through the sciences.

Then I write my letters, rarely any others (except letters concerning business) besides those to my two friends, Bonstetten and Kinloch.

[...]Mr Kinloch sees Italy with the eyes of a man devoted to great occupations, with the sensitivity of a friend of antiquity and the fine arts. His letters are a diary of everything he sees, hears and feels. Through him and that other friend, I know Italy better than almost any other country.

April 1777, to his brother

When you wrote to him, I was in Lyon. My friend Kinloch, when he returned from Italy, wrote to me to find me at the lake below Genthod on a specific day, because he wanted to visit me; I however could not wait for him and took a cabriolet. I met him three hours from Geneva. He stayed with me for three or four days.

He strengthened his admiration for the monuments of the ancients when he saw them; his love of free government when he saw the current state of the nation and the constitution; and through everything, history, art and intercourse, he strengthened his noble desire for rightful fame and great virtues: and as he saw so many others, he learned to estimate my friendship even more highly. And it really seems to me that we loved each other ten times more during these few posts, and the purpose of our friendship is always our mutual perfection; nor does Kinloch want any other friend, and I do not want any others besides Bonstetten and him.

When he left Genthod and we had read and spoken a lot together, it was not possible for me to watch him go; so I went to Lyon. [...] I am never happier or healthier, nor do I think more clearly or feel more vividly, than when I am travelling; hence, I made a lot of observations and at the same time did a lot of work, both with my friend and after we left Lyon - at the same hour but by different routes - and I drove back.

I read everything to him that I had drafted about Switzerland over the winter, then we read several works by Juvenal with endless pleasure, from which I am also learning several parts by heart, and then we read about the countries that we had seen, besides many chapters from Montaigne, whose masterwork is the chapter on friendship*

*Michel de Montaigne’s famous essay De l’amitié (On friendship) was written after the death of his beloved friend Etienne de la Boétie. Montaigne posits that a person can only have very few - or even just one - true friends, a position based on his profoundly deep love for Boétie, whose death just four years into their acquaintance devastated him. Müller and Kinloch would have seen a close mirror of their own relationship in this, built as both were on intellectual pursuits and mutual self-improvement, and with a subtle but present homoromantic undertone. Read an English translation of the essay here, where Montaigne outs himself as team-Achilles-was-the-bottom.

4 Sept 1779, to his brother

It was with unspeakable pleasure that I received news from Kinloch a few days ago that, after feeling forced by mortal danger to take up arms for Carolina, he had distinguished himself so much as aide-de-camp in Georgia and Carolina under General Moultrie that, in a letter to the Congress, the general named him a very brave youth and the pride of his fatherland, and this was printed in the newspaper. This fame that my friends acquire is a powerful spur for me.

29 July 1776, to his father

Die erste Ursache meines langen Stillschweigens, l. P. ist, daß mein einförmiges Leben mir wirklich wenig zu schreiben darbietet; die andere: daß ich sehr beschäftiget bin. Ein paar Stunden lese ich mit meinem Freund, und das ist fast die einige Zeit, welche ich der Lecture widmen kann.

10 Oct 1776, to his father

Die Ursache meines langen Stillschweigens errathet ihr, liebster Papa; wenn man an einem wichtigen Werk arbeitet, so ist man ganz dieses Werkes; und denn vollendete ich mit meinem Freund Kinloch noch einige Bücher.

[...] Ein Buchhändler von Neufchatel, Frau B. und ich haben Herrn B. zu einer Sammlung seiner somtlichen Werke vermocht. Bei dieser Gelegenheit durchsieht er sie alle, und macht Zusäße und Veränderungen. Da er selbst nicht lesen darf, so wünschte er mit einem Freund diese Schriften zu durchgehen, dem zugleich der Inhalt geläufig wäre. Zu dem Ende haben wir diesen Sommer oft 2 – 3 Stunden des Abends diese und andere Schriften in Herrn Kinlochs Gegenwart gelesen.

[...] Mein Freund K. geht nach Italien. Es ist hart; aber der nordamerikanische Krieg und mein Werk, welches zu sehr unterbrochen worden wäre, verhindern mich ihn zu begleiten. Dieser Brief ist nicht lang genug, um Euch, auszudrücken, wie schmerzlich mir übermorgen dieser Abschied seyn wird.

[...] Der Verlust meines Freundes macht mich traurig. Zum Glück ist Kinloch in allen Welttheilen mein; unsere Personen mögen getrennt werden, aber nicht unsere Gemüther; seine Vervollkommnung soll mir mehr am Herzen liegen, als seine Gegenwart; endlich in der langen Laufbahn, welche der Natur nach uns offen ist, mögen wir uns wohl zusammen finden *..

* Diese Freundschaft mit Herrn Kinloch blieb ungeschwacht bis zu Müllers Tode. Er erhielt zu Cassel noch Briefe von ihm.

24 Dec 1776, to his brother

Für mich selbst suche ich nichts, als jene Unabhängigkeit, welche ich für das höchste Gut eines Menschen halte, deren ich nun genieße, und durch den Edelmuth meines Freundes Kinloch und durch die Wissenschaften allezeit genießen werde.

Alsdann schreibe ich meine Briefe, selten andere (außer Briefe die Geschäfte betreffen) als an meine zwei Freunde, Bonstetten und Kinloch.

[...]Herr Kinloch sieht Italien mit den Augen eines Mannes, der sich den großen Geschäften widmet, mit der Empfindlichkeit eines Freundes der Alten und der schönen Künste. Seine Briefe sind das Tagbuch alles dessen, was er sieht, hört und fühlt. Durch Ihn und jenen andern Freund kenne ich Italien genauer als fast kein anderes Land.

April 1777, to his brother

Als du ihn schriebest, war ich zu Lyon. Mein Freund Kinloch, als er aus Italien zurückkam, schrieb mir an einem gewissen Tag mich am See unter Genthod zu finden, weil er mich besuchen wolle; ich konnte ihn aber nicht erwarten und nahm ein Cabriolet. Drei Stunden von Genf traf ich ihn an. Drei oder vier Tage blieb er bei mir. Er hatte sich beim Anblick der Denkmale der Alten in der Bewunderung derselben, bei Ansicht des heutigen Zustandes der Nation und der Verfassungen in der Liebe freier Regierung, durch alles, Historie, Künste und Umgang in der edlen Begierde verdienten Ruhms und großer Tugenden bestärkt: auch da er so viele andere gesehen hatte, hatte er meine Freundschaft noch höher schätzen gelernt. Und es scheint mir würklich, wir haben einander zehnmal lieber gewonnen in diesen wenigen Lagen, und der Zweck unserer Freundschaft ist allezeit unsere wechselseitige Vervollkommnung; auch will Kinloch keinen andern Freund, ich will auch keinen außer Bonstetten und ihn. Als er Genthod verließ und wir vieles gelesen und gesprochen hatten, war mir nicht möglich, ihn abreisen zu sehen; also ging ich auf Lyon. [...] Niemals bin ich freudiger noch gesünder, auch denke ich nie heller noch empfinde lebhafter, als wann ich reise; daher ich eine Menge Beobachtungen gemacht und zugleich sowohl mit meinem Freund, als nachdem wir Lyon zu gleicher Stunde, aber auf verschiedenen Wegen, verlassen und ich zurückfuhr, sehr viel gearbeitet habe. Ihm las ich alles, was ich diesen Winter über die Schweiz abgefaßt hatte, dann lasen wir mit unendlichem Vergnügen verschiedene Stücke im Juvenalis, aus welchem ich auch mehreres auswendig lerne, und dann lasen wir über die Länder, die wir sahen, nebst vielen Kapiteln im Montaigne, dessen Meisterstück das Kapitel von der Freundschaft ist;

4 Sept 1779, to his brother

Vor wenigen Tagen habe ich mit unsäglichem Vergnügen von Kinloch Nachricht bekommen, daß, nachdem er sich durch Lebensgefahr gezwungen gesehen, für Carolina die Waffen zu ergreifen, er unter General Moultrie als Aide de Camp in Georgien und Carolina sich so sehr ausgezeichnet, daß er von dem Feldherrn in einem Brief an den Congreß ein sehr tapferer Jüngling und eine Ehre seines Vaterlandes genannt worden ist, welches gedruckt worden. Dieser Ruhm, den meine Freunde erwerben, ist für mich ein gewaltiger Sporn.

4 Sept 1779, to his brother

Vor wenigen Tagen habe ich mit unsäglichem Vergnügen von Kinloch Nachricht bekommen, daß, nachdem er sich durch Lebensgefahr gezwungen gesehen, für Carolina die Waffen zu ergreifen, er unter General Moultrie als Aide de Camp in Georgien und Carolina sich so sehr ausgezeichnet, daß er von dem Feldherrn in einem Brief an den Congreß ein sehr tapferer Jüngling und eine Ehre seines Vaterlandes genannt worden ist, welches gedruckt worden. Dieser Ruhm, den meine Freunde erwerben, ist für mich ein gewaltiger Sporn.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francis Kinloch in Müller's letters to his family: Part 3

These extracts are from Johannes von Müller: Sämmtliche Werke, volume 7 (1810).

My translations here, original German transcriptions below the cut. Müller and Kinloch have set off on their tour of Switzerland!

21 Aug 1775, to his brother

From there a narrow, steep path leads between sheer drops and vertical mountains into the Weissenburg hot spring, travelled only by pedestrians. Imagine the most terrible rock faces, with water rushing down and partially breaking up into dust and mist; between these rocks, a forest river flows noisily over rocky ground, over trees that water and wind had torn away from the slopes, and the rubble from the mountains that had broken them loose and thrown them down. A strong servant from the baths carried Mr. Kinloch and me on his back through this river to the healing spring.

21 Sept 1775, to his father

We drove in a Bernese carriage through Freyburg to Affry Castle, where the awful roads necessitated us to send the carriage home. After 2 hours, we came to Cicogne, where with some effort, we managed to interpret out of the patois of the people that we had taken the wrong road. An old farmer’s wife led us back on track through the muck by moonlight. Beyond the Saanen the path became entirely too difficult. There we rented a miller’s cart. Imagine: our suitcases, me and our dog on this cart, Mr. Kinloch beside us, the servant with a pack on our horse.

[...]

On sunday, Mr Boissier arranged a ball for the whole town in our honour, where everyone had to dance - the farmers and their wives and all sons and daughters, and Mrs Boissiere, and Mr von Castela and Mr Kinloch and even Mr Boissier himself - though he is lame - and even I - though I cannot dance very well. This day I translated an Italian opera into French. I forgot to mention the letters that we received at Berne, Mr K one from America, I one from England from Mr Thomas Boone

Undated, 1775, to his brother

My dear brother! I cannot describe my contentment to you enough. [...] I am loved, and friendship is the joy of my life. My Englishmen, my American,* Bonstetten, Tronchin, Bonnet!

*Kinloch

20 March 1776

At the moment, Kinloch and I are reading Tacitus for the second time (me, for the third) [...] Mr Bonnet is giving us 2–3 lectures a week on psychology. But don’t imagine him as an ordinary professor, he does not allow himself to be paid except in the attention and friendship of his audience, and these are only two, Kinloch and me. We go to him at 4pm, his psychology lesson starts at 5 or 6, and we stay until 11.

June 1776, to his brother

Letters from England have convinced Mr Kinloch to move his planned journey forward to the autumn.

21 Aug 1775, to his brother

Von da führt ein schmaler abhängiger Weg zwischen Abgründen und senkrechten Bergen in das warme Bad Weissenburg, niemanden als Fußgänger. Stelle dir die schrecklichsten Felswände vor, mit Wassern, welche da herunter stürzen und sich zum Theil in Staub und Nebel auflösen; zwischen diesen Felsen wälzt sich mit großem Geräusch ein Waldwasser über einen felsigen Grund, über Bäume, welche Wasser und Wind ab den Gebürgen gerissen und Trümmern von Bergen, welche sie abgelöset und herabgewälzt hatten. Durch dieses Wasser trug Hrn. Kinloch und mich ein starker Badknecht auf dem Rücken zu der heilsamen Quelle.

21 Sept 1775, to his father

In einer Bernerkutsche fuhren wir über Freyburg nach dem Schloß Affry, woselbst die schlimmen Straßen uns nöthigten, die Kutsche heimzusenden. Nach 2 Stunden kamen wir auf Cicogne, wo wir mit Mühe aus dem Patois des Volks erdollmetschen konnten, daß wir den unrechten Weg eingeschlagen. Eine alte Bauersfrau führte uns durch den Koth beim Mondschein zurechte. Jenseits der Saanen wurde nun der Weg allzu arg. Daselbst mietheten wir einen Müllers - Karren. Stellet Euch vor, unsre Mantelsäcke mich und unsern Hund auf diesem Wagen, Hr. Kinloch neben her, den Bedienten mit einem Pack auf unserm Pferd.

[...]

Am Sonntag gab Hr. Boissier unsertwegen dem ganzen Dorf einen Ball, wo alle Bauren und Bäurinnen und alle Knaben und Töchtern, und Mad. Boissiere, und der Hr. von Castela und Hr. Kinloch, und Hr. Boissier selbst, ob er wohl estropirt ist, und selbst ich, ob ich gleich nicht wohl tanzen kann, tanzen mußte. Diesen Tag übersetzte ich eine italiänische Opera ins Französische. Ich habe vergessen, der Briefe zu gedenken, welche wir zu Bern erhalten, Hr. K. einen aus Amerika; ich einen aus England von Herrn Thomas Boone

Undated, 1775, to his brother

Mein lieber Bruder! Ich kann dir mein Wohlbefinden nicht genug beschreiben. [...] Man liebt mich, und die Freundschaft ist meines Lebens Lust. Meine Engländer, mein Amerikaner, Bonstetten, Tronchin, Bonnet!

20 March 1776

Gegenwärtig lesen Kinloch und ich zum andern (ich, zum dritten) Mal den Tacitus [...] Herr Bonnet giebt uns wöchentlich 2–3 Lectionen über die Psychologie. Stelle ihn dir aber nicht als einen gewöhnlichen Professor vor, er läßt sich nicht anders bezahlen, als durch die Aufmerksamkeit und Freundschaft seiner Zuhörer, und dieser sind nur zwei, Kinloch und ich. Wir gehen um 4 Uhr zu ihn, um 5 oder 6 fängt er seine psychologische Stunde an, und wir bleiben bis um 11 Uhr

June 1776, to his brother

Briefe aus England haben Hrn. Kinloch bestimmt, seine vorgehabte Reise auf den Herbst zu verschieben.

#francis kinloch#johannes von müller#karl viktor von bonstetten#18th century history#queer history#these extracts have it all#moonlit wandering through the fields#carried across a river by a hunky fella#dog!!!#presumably the small lapdog variety if it's riding in the cart#country ball where even poor müller is forced onto the dancefloor

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francis Kinloch in Müller's letters to his family: Part 2

These extracts are from Johannes von Müller: Sämmtliche Werke, volume 7 (1810).

My translations here, original German and French transcriptions below the cut. Paragraph breaks added for clarity, and descriptive passages included in full for the Vibes.

19 May 1775, to his family

My situation is the happiest that you can imagine; the view from here is, beside the one from Bessinge, the most beautiful in the area; the clear view over the lake and into Switzerland is better than from Bessinge; my house is on a hill, the banks are covered with meadows, gardens and vineyards and appear to me like a great garden;

my friend is one of the most virtuous and flawless men, and our new occupation is the mutual effort to make each other ever more perfect; our business is that which I would choose from among all the occupations of humankind; everyone, even the farmers of the town, praises our quiet and industrious life.

It is quiet without being lonely, because many of our friends visit us now and then, or we them, for lunch or supper. A few days ago we were in Bessinge, yesterday Mr Tronchin came to me, on Tuesdays we are invited to dine at his home. At the end of the month, Bonstetten will come to me for a few days.

Everyone endeavours to contribute to our pleasure, and never in my life have I enjoyed something so great, so innocent, so full of learning. Although we have only been here for 19 days and are not bored, I feel like it has been 19 weeks: we have worked so much and it seems so improbable that I would be able to do all of this in so few days.

6 June 1775, to his family

An extract of a letter from Mr Thomas Boone, Esq., Mr Kinloch’s guardian: “With infinite pleasure, I assure you that of all the deeds undertaken by my young friend since he left me (and he has not done any that displease me), none have met with so much of my approval as the attainment of your friendship. If he had sought out scenes of luxury and wastefulness, he could have obtained the acquaintance of young people of the highest rank; closeness with the man of merit, genius and learning is not so easily established: planning, a desire to learn and morals are part of this. To attain your friendship, Kinloch must have had merits. As his friend, you will be pleased to hear from me that in his entire life he never made an acquaintance that was not creditable to him. I have sincerely discovered such insight, such cleverness in him, that I have decided to let him be the master of all his future dealings. I ask that you convey this to him; he will hear it with doubled pleasure from the mouth of his friend. Wherever you may be with him, he will, I am sure, learn more with you than at any other place. When he enters onto a larger stage, I will advise him thus: at present he needs no guidance but yours. I approve of your plan entirely. You made Kinloch and me happy.”

I wrote to Mr Voltaire, who lives very close to us, a few days ago to say that K and I would like to come to him. [...] As he presented Mr Kinloch to the ladies, he said: “Here is a man, who comes from the land of savages but who does not look it!” He asked me where my tutor was? And then said to those present: “this young man with the face of a fifteen-year-old is himself a tutor; but simultaneously a historian of Switzerland; he has, like Aeneas, journeyed to the shade, that is to me.” Soon thereafter we were like old acquaintances. He has published a new text on the existence of god. The tall olive-coloured savage and the young delicate Swiss historian send their friendly greetings.

July 1775, to his parents

After a few days, according to his promise, my friend Mr v. Bonstetten came to me and also stayed with us, to our great joy. Our rooms are currently all occupied and my happiness has naturally been greatly multiplied by the union of my two friends, the white and the brown.*

[...]

My friend Kinloch and I are thinking to leave Chambeisi towards the end of August. From there to Lausanne, to Vivis, through the Bernese highlands to Thun, up along the Thun and Brienz lake to Haßli, over the mountains into the Urfern valley, out to Altdorf, overland to Unterwald, overland to Schwyz, past Gersau to Lucerne and Zurich, along the lake to Glarus, down the Rhine valley to Appenzell and St Gallen, from there to Constanz, and from there to Schaffhausen, through the four forest towns to Basel, through Pierre Petruis to Solothurn, then Neufchatel, Bern, Freiburg in Uechtland, Valeyres, back to Chambeisi through Waat, where we spend the winter with the sciences and Mr Bonnet's friendship.

*Kinloch, who appears to have had a notably darker or more tanned complexion to those around him.

A map of the route, as best as I could get it to match up. Click for better quality, or view the interactive version here.

19 May 1775, to his family

Meine Lage ist die glücklichste, die du dir vorsstellen kannst; die Aussicht von hier ist nebst der von Bessinge die schönste dieser Gegenden; vor der zu Bessinge hat sie den offnern Horizont den See hinauf und in die Schweiz zum Voraus; mein Haus ist auf einem Hügel, die Ufer sind mit Wiesen, Gärten und Wein bewachsen und fallen wie ein großer Garten in mein Auge; mein Freund ist einer der tugendhaftesten und vollkommensten Männer, und unsere einige Beschäftigung ist die gegenseitige Bemühung, einander immer vollkommener zu machen; unsere Geschäfte sind solche, die ich unter allen Beschäftigungen der Menschen auswählen würde; jedermann, selbst die Bauren des Dorfs, rühmt unser stilles und arbeitsames Leben. Still ist es ohne einsam zu seyn, denn viele unserer Freunde besuchen uns bisweilen zum Mittag oder Nachtessen, und wir sie. Vor einigen Tagen waren wir zu Bessinge, gestern kam Hr. Tronchin zu mir, Dienstags sind wir eingeladen bei ihm zu speisen. Am Ende des Monats wird Bonstetten auf einige Tage zu mir kommen. Jedermann bemühet sich zu unserm Vergnügen beizutragen, und in meinem Leben habe ich nie so vieles, so unschuldiges, so lehrreiches genossen. Ob wir wohl erst 19 Tage hier sind und keine Langeweile haben scheint mir diese Zeit 19 Wochen zu seyn: so viel haben wir gearbeitet und so unwahrscheinlich scheint es mir, daß ich dies in so wenigen Tagen habe thun können.

6 June 1775, to his family

Auszug eines Briefes von Hrn. Thomas Boone, Esqu. Hrn. Kinlochs Vormund: “Mit unendlichem Vergnügen versichere ich Sie, daß unter allen Handlungen meines jungen Freundes, seit er mich verlassen (und er hat keine vorgenommen, die mir mißfallen) keine bei mir soviel Beifall gefunden, als die Erlangung Ihrer Freundschaft. Wenn er sich in Scenen von Wohlleben und Verschwendung begeben hätte, so hätte er die Bekanntschaft junger Leute vom ersten Rang erhalten können; Vertraulichkeit mit dem Mann von Verdienst, Genie und Gelehrsamkeit ist nicht so leicht errichtet: Plan, Lernbegierde und Sitten gehdren hiezu. Ihre Freundschaft zu erlangen, mußte Kinloch Verdienste haben. Sie werden als sein Freund mit Vergnügen von mir vernehmen, daß er in seinem ganzen Leben keine Bekanntschaft gemacht, die ihm nicht rühmlich gewesen. Ich entdecke wirklich solche Einsichten, solche Klugheit bei ihm, daß ich beschlossen habe, ihn künftig Meister aller seiner Handlungen zu lassen. Ich bitte Sie, sagen Sie es ihm; mit doppeltem Vergnügen wird er es aus dem Munde seines Freundes vernehmen. Wo sie auch mit ihm seyn mögen, wird er, das bin ich sicher, bei Ihnen mehr lernen, als an allen andern Orten. Wenn er ein größeres Theater betritt, so will ich ihm rathen; gegenwärtig braucht er keinen Rath als den Ihrigen. Ganz und vollkommen billige ich Ihren Plan. Sie haben Kinloch und mich glücklich gemacht.”

Hrn. von Voltaire, der ganz nahe bei uns wohnt, schrieb ich vor einigen Tagen, daß ich mit K. zu ihm kommen wolle. [...] Als er den Damen Hrn. Kinloch präsentirte, sprach er: “Sehen Sie einen Mann, der aus dem Lande der Wilden kommt und dem man's nicht ausieht!” Mich fragte er, wo mein Gouverneur sey? und dann sprach er zu den Anwesenden: “dieser junge Mann mit dem Gesicht von fünfzehn Jahren ist selbst Gouverneur; aber zusgleich des Schweizerlandes Geschichtschreiber, Er hat wie Aeneas eine Reise zu den Schatten gethan, d. i. zu mir.” Bald darauf waren wir zu Ferner wie alte Bekannte. Er hat eine neue Schrift von der Existenz Gottes herausgegeben. Der große olivenfarbige amerikanische Wilde und der junge zarte Geschichtschreiber der Schweiz entbieten ihren freundlichen Gruß

July 1775, to his parents

Nach einigen Tagen kam zufolge seiner Zusage mein Freund, der Herr v. Bonstetten, zu mir und blieb zu unsrer großen Freude ebenfalls bei uns. Unsre Zimmer sind gegenwärtig alle vertheilt und meine Glückseligkeit ist durch die Vereinigung meiner beiden Freunde, des Weißen und des Braunen, natürlicherweise sehr vermehrt worden.

[...]

Mein Freund Kinloch und ich gedenken Chambeisi gegen Ende des Augusts zu verlassen. Von da nach Lausanne, nach Vivis, durchs Oberland bis Thun, den Thuner- und Brienzersee hinauf nach Haßli, über die Berge ins Thal Urfern, hervor nach Altorf, anzuländen in Unterwalden, anzuländen in Schweiz, Gersau vorbei nach Luzern und Zürich, den See herauf nach Glarus, das Rheinthal herunter nach Appenzell und St. Gallen, von da nach Constanz, und von da nach Schaffhausen, durch die vier Waldstädte nach Basel, durch Pierre Pertuis nach Solothurn, hierauf Neufchatel, Bern, Freiburg im Uechtland, Valeyres durch die Waat zurück nach Chambeisi, woselbst wir bei den Wissenschaften und Herrn Bonnets Freundschaft den Winter zubringen.

#francis kinloch#johannes von müller#18th century history#queer history#the german version of the voltaire story was much clearer#god i love a map

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francis Kinloch in the Müller-Bonstetten letters (and others): Part 5

More translations, taken from various sources (here, here, here and here). The letters are to Bonstetten unless otherwise noted. Biographical details sourced from Kinloch of South Carolina.

13 May 1780

Because of Mr Kinloch, I am filled with joy and dread. Dread, because his city has been besieged by 10,000 men with a great deal of artillery; joy, because he has married a very amiable and wealthy woman*. I receive regular letters from his brother; his own are often lost due to the perils of war.

*Kinloch’s first wife was Mildred Walker, though it seems they were only married on 22 Feb 1781. She died in Nov 1784.

9 Sept 1780

Kinloch, after having performed bravely in various engagements, was wounded in the arm, whereupon South Carolina unanimously elected him as a delegate to the Continental Congress; he sits with his colleagues in Philadelphia, not very peacefully, I think.

11 Aug 1781

I spent two days sorting more than 500 letters that came from Geneva along with my books. Memories of Kinloch, Nassau, Bonnet, Tronchin, Boone, Knight, Sandys, Abbot sweetened the work

7 Dec 1782, to his mother

I have largely been happy with my life up until now: but almost never on the path that I intended to take. Twelve years ago, I wished to marry*, and to live in Schaffhausen on a few professorships; I then had various plans for England and Flanders; at one point, the greatest and best thing seemed to me to witness the blossoming and progress of a new free country with Kinloch, and the serve a free people in war and peace;

*Original annotation: The desire lasted only a few days.

January 1784

It is neither my place to compare myself with such writers nor to scorn what God has given me: but after almost losing many years of my early youth, the 33rd [year] is finally here, but in an occupation to which I was not suited, the 24th and 25th I spent with Kinloch, leaving me little time for my own studies of friendship and duty

9 Aug 1786

Nothing else has changed in my household, except that Mr Boone, Kinloch’s former guardian and governor of South Carolina, has sent his son here, and he is living with me; he does not take up any of my time, as I only see him at mealtimes; he is an amiable officer, who was also very popular at Aschaffenburg.*

*A town in Bavaria.

20 Feb 1801

In my letter writing, I had to ensure that there was also a reply to Kinloch in South Carolina. Do you remember the noble youth? Now he is a grandfather;* he lives happily besides and I have just read an excellent essay of his about the character of the revolution.**

*Kinloch’s daughter, Eliza Kinloch Nelson, gave birth to a son called Francis in 1800.

**From context, the French rather than American revolution.

7 Jan 1803

Not enjoyable, as you can see, but rather tender in its sufferings and joys was the transition into my 52nd year. On that birthday I wrote to South Carolina, responding to two of Kinloch’s letters, full of spirit and love.

22 Oct 1803

I already wrote to you that Kinloch has arrived in Bordeaux and will soon be in Geneva; he wrote to me at once in such a brotherly way, rejoiced at the long-awaited reunion, and for a few days took me back to the charming dreams of my youth! I answered him immediately; we shall see each other in the coming year. If nothing unusual happens, I can easily get a few months' leave; should it not be possible from this or that perspective, then the one who has crossed the ocean and all of France will also make these 60 posts himself.

25 Jan 1804

Write to me in Dresden at once. If the world quietens, or at least does not continue to burn, I hope to visit you and Kinloch in the summer.

18 June 1804

To Geneva, first, came the most beautiful letters from Berlin, gracious, joyful, inducing longing. Then Kinloch’s embrace! he is as he was; slightly fatter; his heart noble, as before; a husband, like you; a caring father; a faithful brother; a morally perfect person.

13 May 1780

Ich bin wegen Hrn. Kinloch in großer Freude und Furcht. In Furcht, weil seine Stadt von 10,000 Mann mit vieler Artillerie belagert wird; in Freude, weil er eine sehr liebenswürdige und reiche Frau geheirathet hat. Von seinem Bruder bekomme ich öftere Briefe; die seinigen gehen durch die Kriegsgefahren häufig verlohren.

9 Sept 1780

Kinloch, nachdem er sich in verschiedenen Treffen tapfer gehalten, ist am Arm verwundet worden, worauf Südcarolina ihn einmüthig zum Deputirten auf den Generalcongreß erwählt hat; er sitzt mit seinen Collegen zu Philadelphia, nicht eben ruhig, denke ich.

11 Aug 1781

Zwei Tage sind mir über der Anordnung von mehr als 500 Briefen, die nebst meinen Büchern aus Genf gekommen sind, verflossen. Manche Erinnerung an Kinloch, Nassau, Bonnet, Tronchin, Boone, Knight, Sandys, Abbot, versüßte die Arbeit

7 Dec 1782, to his mother

Ich bin in meinem Leben bis dahin meist glücklich gewesen: fast nie aber auf dem Weg, den ich gehen wollte. Vor zwölf Jahren wünschte ich zu heirathen*, und mit ein Paar Professorstellen zu Schaffhausen zu leben; ich hatte nachmals auf England und Flandern verschiedene Plane; einst schien mir das größte und beste, mit Kinloch dem Aufblühen und Fortgang eines neuen Freistaates beizuwohnen, und im Krieg und Frieden einem freien Volk zu dienen;

*Der Wunsch dauerte nur wenige Tage.

January 1784

Es kömmt weder mir zu, mich solchen Schriftstellern zu vergleichen oder zu verachten, was Gott auch mir gegeben: aber nachdem ich viele Jahre der ersten Jugend fast verloren, das 33ste endlich hier, aber in einer Beschäftigung, für die ich nicht war, das 24ste und 25ste mit Kinloch, so daß mir für eigene Studien von Freundschaft und Pflicht wenige Zeit gelassen wurde

9 Aug 1786

In meinem Hauswesen hat sich weiter nichts verändert, als daß Hr. Boone, Kinloch's ehmaliger Vormund, und von Südcarolina Gouverneur, seinen Sohn' hieher gesandt, welcher bei mir wohnt; Zeit kostet er mir keine, da ich nur bei Tafel ihn sehe; er ist ein liebenswürdiger Officier, der auch zu Aschaffenburg sehr wohl gefallen.

20 Feb 1801

Von meiner Briefschreibung muß ich nachholen, daß auch nach Südcarolina an Kinloch eine Antwort dabei war. Erinnerst du dich des edlen Jünglings? Nun ist er Großvater; lebt übrigens glücklich und ich habe so eben einen vortrefflichen Aufsatz über den Charakter der Revolution von ihm gelesen.

7 Jan 1803

Nicht lustig war, wie du siehst, aber zärtlich in Leiden und Freuden der Uebergang in mein 52stes Jahr. An dem Geburtstag wurde nach Südcarolina geschrieben, auf zwei Briefe Kinloch's voll Geist und Liebe.

22 Oct 1803

Schrieb ich dir schon, daß Kinloch zu Bordeaux angekommen ist und nun zu Genf seyn wird; wie brüderlich er mir sogleich schrieb, des lang ersehnten Wiedersehens frohlockte, und für einige Tage mich ganz in der Jugend holde Trăume zurück versehte! Ich habe ihm sogleich geantwortet; sehen werden wir uns im zukünftigen Jahr. Wenn nichts besonderes eintritt, so kann ich Urlaub auf ein paar Monate leicht erhalten; sollte es aus der oder der Betrachtung nicht seyn können, so wird der über das Weltmeer und ganz Frankreich Hergekommene auch diese 60 Posten selbst noch machen.

25 Jan 1804

Nach Dresden schreibe mir sogleich. Wenn die Welt ruhig, oder doch nicht weiterhin entflammt wird, so hoffe ich auf den Sommer Euch und Kinloch zu besuchen.

18 June 1804

Zu Genf erstlich die schönsten Briefe von Berlin, gnädig, freudevoll, sehnsuchterregend. Dann Kinloch's Umarmung! er ist, wie er war; etwas fetter; sein Herz edel, wie vorhin; ein Gatte, wie du; ein sorgsamer Vater; ein treuer Bruder; ein moralisch vollkommener Mensch.

#francis kinloch#johannes von müller#karl viktor von bonstetten#18th century history#queer history#“the desire lasted only a few days” 😭

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

28th On the morning of the Twenty Eighth Col. Lawrence being advanc'd with about Forty Men, and one Howett [howitzer] Discovered the Enemy landing, in number about 150, his great Eagerness to Ingage, provented his waiting the Arrival of the main body under Gen. Gest who was about two miles in Rear, and coming forward with Giantick Strides, I say his Eagerness would not parmitt him to wait, but precipetately Ingaged, and in a few Minuts fel a Victom to his own In-advertance, by the well Directed Fire of the Enemy; By his fall the State lost a worthy Citizen_

Captain Walter Finney's diary entry for 28 August 1782

Finney, W., & Boyle, J. L. (1997). The Revolutionary War Diaries of Captain Walter Finney. The South Carolina Historical Magazine, 98(2), 126–152. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27570228

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I also saw La Fayette, whose character having been at one time elevated far beyond its intrinsick merit, has been since as unjustly decried. His object was probably never well defined even to himself, but that he meant the good of his country, connected indeed with his own exaltation, is not, I think, to be doubted. What the effect of the revolution will ultimately be to France, we are yet to learn, but to him it has been certainly productive of every ill. It has robbed him of rank, fortune, and friends, and has subjected him to exile, to imprisonment, and to disgrace.

He nevertheless looks better than when I knew him many years ago, during the war, and has an air of tranquillity, and I should say of contentment, if I thought it possible, for he cannot but have some bitter moments; moments during which reflections must force themselves upon him [...]

It is singular, that of all the various parties which have succeeded each other in France, no one has expressed itself satisfied with the conduct of La Fayette. [...]

You will say, perhaps, that I do not speak as advantageously as I ought of our old friend the Marquis; but his conduct was perhaps never strictly proper; and with respect to America, I do not think it will be approved hereafter, when passion shall have given way to reason. He had made every preparation for an excursion to Greece and Asia Minor in '76, when it was accidently suggested to him that he might serve his country and acquire reputation by taking part with the Americans. Animated by the hostility of a Frenchman towards the ancient rivals of his nation, his object was to render the breach irreparable between the colonies and the mother country

Francis Kinloch, Letters from Geneva and France (1819)

#marquis de lafayette#francis kinloch#18th century history#amrev#frev#no but tell us what you really think

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw Kosciusco, who served with reputation against Burgoyne, and in South Carolina, and who has since acted so distinguished a part in Poland; he lives in the outskirts of Paris in the family of a friend whose children play about him, and here he reads the newspapers, and cultivates his garden, and smokes his cigar, forgetting the world as much as possible, and striving, I really believe, to be forgotten.

The sight of Kosciusco reminded me of his friend and countryman Pulawski, whom I had known during our revolutionary war; and to whose merit, as I look back upon what I remember to have been the opinion of those times, I do not think we did justice. What appeared rashness to us, was a well placed confidence in his knowledge of the partisan war, and in his own personal prowess. In mixed companies, and in a drawing room, there was something of awkwardness, I had almost said of timidity, in his manners and appearance, but on horseback, and at the head of his corps, he bad the air of the God Mars.

Rulhiere has given an account of this distinguished family of Pulawski in his late work on Poland. You would be struck with the resemblance in some circumstances between the old Pulawski, as he was called in the papers of the day, and the elder Brutus in Roman history. There was the same forbearance for years under injuries and insults, the same fearless exertion afterward, and the same devotedness in death to the cause of the republick.

Francis Kinloch, Letters from Geneva and France (1819)

#tadeusz kościuszko#kazimierz pułaski#francis kinloch#18th century history#amrev#polish history#can't help agreeing with the observation that kościuszko just wanted to be forgotten

6 notes

·

View notes