Text

Mistakes were Made. (And, Yes, by Me.)

It’s part of human nature to want to be right. It informs our view of our self, and, especially if we take a public stand, we commit to it much more strongly than we would otherwise. In his excellent book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Robert B. Cialdini devotes an entire chapter to it—Commitment and Consistency. Once we commit to something and take a stand, we are loath to change our minds, even in light of new information that contradicts our stance. Of course, this sometimes leads to huge mistakes, and is often the reason our investments go awry. We hate cogitative dissonance and will usually do anything to hang on to our stated positions, even when, especially when, they are wrong.

I thought it would be an interesting exercise to look at all the times where I got it almost entirely wrong, not for self-abasement, but rather as an exercise in how we can learn from our mistakes and still go on to do very well in life and our chosen careers. Thus, in no particular order, let’s look at things I got wrong, and what I learned:

1. An early faith that no-load funds would destroy those offered by financial advisors for a fee lead me to miss a huge opportunity.

In the mid-1990s, I had a relationship with one of the biggest brokerage houses in the United States, and after the initial publication of my book, What Works on Wall Street, my firm was enjoying a lot of interest from investors. We decided to open a mutual fund family, and one of my colleagues at the brokerage house suggested that I open load funds, so that their army of advisors could offer them to the public. The advisors at the firm were already offering another portfolio of mine and everyone I talked to brokerage thought that this was an easy decision. It would have allowed my firm to take huge advantage of the momentum we were having in other areas of our business and give the brokerage firm’s advisors access to what were among the first factor-based funds. I declined.

My unwavering belief that no-load funds were the only future led to a huge mistake. I didn’t understand then, as I do now, that investors who have help with their investments from advisors many times have an advantage over someone simply left to their own devices. I was in my mid 30s and believed that it was

obvious

that all investors would go the no-load route and

oblivious

to the fact that at that time, most investors preferred to work with advisors (And still do.) What could have been a huge jumpstart in the mutual fund business was lost, and even though our no-loads did okay in attracting investors, I missed several obvious opportunities for my firm. Indeed, at the time, we called our funds “Strategy Indexes”

which would have given us an enormous head start on what have come to be called Fundamental Indexes, so, this error had a compounding effect.

I think the lesson here is understanding that just because you have a belief or preference, however strongly held, it doesn’t negate those who differ with you. Being a true believer in almost anything does not lead you to make the best choices nor does it allow you to approach things with a more open mind. Had I been less dogmatic, I could have taken advantage of a rare opportunity for my relatively new investment management firm to partner with one of the most powerful brokerage firms on the street and potentially popularized factor-based investing to a wide group of investors much earlier than ended up happening. I think the important lesson here is that there are many legitimate paths to succeeding, and you should avoid dogmatic responses and keep an open mind, as long as the alternatives are legitimate and can help others.

1. In the first few editions of my book, I proclaimed price-to-sales to be the “King of Value Factors.”

In 1996, when the first edition of my book came out, I was super excited to be offering a compendium of the actual long-term results of all of Wall Street’s favorite measurements for determining if a stock was a good investment or not. At the time, I only looked at individual factors and price-to-sales proved itself to be head-and-shoulders above all the others. Other than a great book by Ken Fisher called Super Stocks, which focused on how great the price-to-sales ratio was, at the time, it was a very obscure factor that wasn’t popular like PE or Price-to-book. That made me even more excited to proclaim it the “King of Value Factors.”

With hindsight (another nasty behavioral bias), this was a rookie mistake. Had I given it any thought, I would have remembered that you can make anything look good if you varied the amount of time in your analysis. But I thought, gosh, this is decades of data, surely things won’t change that much going forward. But, of course, they do. Instead of focusing on how value factors in general did in identifying attractive stocks, I rushed to proclaim price-to-sales the winner. That was, until it wasn’t. I guess there’s a reason for the proclamation “The king is dead, long live the king” when a monarchy changes hands. As we continued to update the book, price-to-sales was no longer the “best” single value factor, replaced by others, depending upon the time frames examined. I had also become a lot more sophisticated in my analysis—thanks to criticism of my earlier work—and realized that everything, including factors, moves in and out of favor, depending upon the market environment. I also realized that you were far better off seeing how a stock scored on a composite of value factors that took more aspects of the balance sheet into account.

The lesson? No single factor or fundamental piece of data is ever the answer or solution to the complicated question of how to pick stocks that outperform. For example, I have long been a fan of shareholder yield (Dividends+Net buy backs) but even though it performs well on its own, it performs much better when selected from a group of stocks that are very cheap; have good earnings quality and have a high conviction in their buybacks, as evidenced by percentage of outstanding shares they are buying. As Einstein is reputed to have said, “make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

2. In the late 1990s, I was approached by the American Stock Exchange to do a series of ETFs based upon What Works on Wall Street. I declined.

This one makes me feel like Forrest Gump, only in reverse. I’ve recently read an interesting article on how our memories play tricks on us and fill in details that never actually happened, probably so that we can keep a consistent view of ourselves and decisions that we make. Luckily, I have been an inveterate journal keeper, so I am able to go back and see what I was thinking without the benefit of hindsight or new magical details inserted by my comforting brain. ETFs were pretty much brand new at the time, and I thought they were a great idea, but having just launched a mutual fund family, I was worried about channel conflict. I was also worried about endorsing a new, and as of that time, untested investment vehicle. (As you will see later in this post, I quickly overcame my objections to that at precisely the wrong time.) On top of these concerns, the fees would be tiny by the standards of the late 1990s. So, I passed.

I think the main lesson here is that sometimes you just need to jump in with both feet if you think something is a great innovation and worry about the other concerns later. I knew that ETFs offered several very attractive improvements over mutual funds, and I had the opportunity to have a large partner launch tie-in strategy with What Works on Wall Street. What’s more, we got on the investment world map by offering something that was new at the time—factor-based portfolios. I should have thought more deeply about how well two innovations tied together could have worked. But, I didn’t. I let the circumstances of the moment—new way of investing; new mutual fund family, relatively new company—blind me to the strategic opportunity at hand. I let tactics trump strategy, and I’ve come to believe that tactics should always be the servant to strategy.

1. I started a company called Netfolio in 1999. It was one of the first robo- advisors and I got a U.S. Patent for a “System and method for selecting and purchasing stocks via a global computer network.” In early 2000, I got a massive financial offer to buy a portion of the company from one of the largest Investment Banks on Wall Street. I turned them down.

What is it with me and large banks? Obviously, I was as wrapped up in the zeitgeist of the times, which thought that only “pure” online companies would go on to receive multi-billion-dollar valuations. At the time, venture capitalists and professional investors thought it beyond idiotic to have any association with “bricks and mortar” companies. They were so 20th Century. The rules were quite simple (and in retrospect, insane) that only pure-play Internet companies could get the backing to move to IPO, and so, I went against every instinct I had, and said no.

To really show you how easily people, and I mean ALL people, can get caught up in a mania, I made the decision to decline the investment even though I had written a scathing piece in April 1999 called The Internet Contrarian, in which I confidently wrote: “Because the numbers ultimately have to make sense, the majority of all currently public Internet companies are predestined to the ash heap of history. And even if we could see the future and identify the ultimate winner in e-commerce, at today’s valuations it is probably already over-priced.”

So, incredibly bearish on the Internet and the overpriced names, I nevertheless seemed to believe (hope?) that my Internet company was the exception to the rule. After all, there were a number of other VCs who were confidently saying they could offer even better terms without me having to link the company to the offending “bricks-and-mortar” legacy firm, which was, you know, a hugely successful actual business with actual revenues and earnings! Shudder. But such was the mania of the moment that it had all of us—even those of us who in our saner moments had looked at the actual numbers—and determined that the entire thing was unsustainable.

And then, the walls came tumbling down. In March, 2000, an enterprising, smart reporter I know at Barron’s named Jack Willoughby wrote a story called Burning Up in which he pointed out the simple math of the situation: “Internet companies are running out of cash—fast.”

Boom.

It seemed like that one story snapped everyone out of the delusional fantasy that the rules of economics had been repealed and that unicorns and rainbows could be monetized. The other VCs and their better terms? Vanished. Everyone saying legacy companies were destined for the dustbin of history? Silent. Lessons (re)learned?

Many.

I’m lucky that I keep journals in real time, in that it helps me avoid something we all face—hindsight bias. Our brains are very complicated, and they manage to fill in our memories with thoughts we didn’t think at the time; with things we didn’t know at the time. It’s almost impossible for us to accurately recall what we were thinking and the version our brain serves up to us is, to be charitable, very kind to us but also incredibly wrong. Here are some things I wrote down at the time:

1. Be humble—arrogance killed some of the best potential deals in history.

2. Take the money—when someone else wants to give you a lot of money for something you have, let them. Work out the details afterward.

3. Don’t overanalyze—everything will eventually break down and from some angle will not make sense.

4. Understand people’s motives—they are not always what they seem.

5. Understand how fragile the average person is—it will always come out at the worst possible time.

6. Murphy was an optimist—expect six-sigma events as normal, not extraordinary.

In another journal, I wrote that hubris—excessive pride or self-confidence—was an expert assassin of even well-founded hopes and dreams. Whom the gods would destroy, they first make great, especially in their own minds.

What’s the Point?

The point is simple—mistakes provide a lesson-rich environment. But you’ve got to own your mistakes. You’d be compounding them if you tried to point your finger at anything or anyone other than yourself. The most successful people I’ve met have usually also been the ones who not only made the most mistakes but also always owned them. If you have the ability to say “I was wrong” and truly believe and learn from it, you’re close to gaining a new superpower in life.

So many people refuse to own their own mistakes, blaming others, bad luck, bad timing, you name it. If life give you a choice to compete against any type of person, always pick the ones that think most outcomes are due to luck. Does luck play a part? Almost always, but I rarely think—outside of lottery tickets—it’s ever the overriding reason for an outcome. Having the ability to learn all the lessons you can from mistakes you’ve made makes you better prepared for the next time. For as Isaac Asimov said, “in life, unlike chess, the game continues after checkmate.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Additional Thoughts from What Works on Wall Street, 4th Edition in support of AQR’s Recent Paper on Small-Cap Stocks

How Much Better Are Small Cap Stocks?

Most academic studies of market capitalization sort stocks by deciles (10 percent) and review how an investment in each decile fares over time. The studies are nearly unanimous in their findings that small stocks (those in the lowest two deciles) do significantly better than large ones. We too have found tremendous returns from tiny stocks.

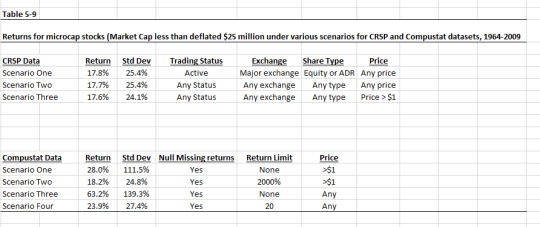

The glaring problem with this method when used with the CRSP and Compustat datasets is that it’s virtually impossible to buy the stocks that account for a large share of the performance advantage of small capitalization strategies. We did a deep analysis of the non-investable microcap stocks (stocks with market capitalizations less than a deflated $25 million) and found that the returns generated were highly contingent on which stocks were allowed into the test and which ones that were excluded. For example, looking at the Compustat universe, Table 5-9 shows a great disparity of returns, depending upon your assumptions. Between 1964 and 2009, if you required stock prices greater than $1, but put no return limit and allowed for stocks with missing data to be included, the portfolio earned an average annual compound return of 28 percent. Yet, when you require that all stocks have share prices greater than $1, have no missing return data and limited the monthly return on any security to 2,000 percent per month, returns decline by approximately 10 percent, and the portfolio earns an average annual compound return of 18.2 percent. Finally, if you add no additional criteria and are willing to allow in any of the microcap names at any price with no return limit, you earn 63.2 percent per year!

Obviously, the data for these non-investable microcap names will lead to very different returns based upon how realistic your assumptions are. Included with the Compustat data is the data from the CRSP dataset, leading me to conclude that if you could buy these tiny names, the most realistic average annual returns are between 17.6 to 18.2 percent over the long term. When you extend the analysis to include the period from July 1926 through December 2009 using the CRSP dataset, the average annual compound return for non-investable microcaps falls to 15 percent per year. Thus, the returns for this group are highly unstable, and the results you see are highly contingent upon which stocks will be allowed and which will be excluded. On December 31, 2009, there were approximately 2,401 stocks in the combined CRSP and Compustat datasets that I define as non-investable micro-cap stocks--where an investment of any size would send their bid/ask spread soaring, making the prices for those stocks a bit of a fiction. If an investor of almost any size –be they an institution or an individual trying to buy a significant position--tried to buy them, their prices would skyrocket.

When you look at the results for investable microcap names, those with market capitalizations between a deflated $50 million and a deflated $250 million, you see that most of the return for tiny stocks disappears; using the Compustat dataset between 1964 and 2009 microcap stocks earned an average annual compound return of 12.70 percent, whereas when using the CRSP dataset over the same period microcap stocks earned 11.82 percent per year. When you use the CRSP dataset to review the full period between 1926 and 2009, the microcap stocks compound at 10.92 percent per year, slightly better than our Small Stocks universe. A far better way to analyze the effects of market capitalization on a company’s returns is to evaluate all fully investable stocks by decile. When you look at the returns to the All Stocks universe by market capitalization decile, a fairly different picture emerges. Looking at Figure 5-2, we see that within the universe of investable stocks, there is an advantage to smaller cap stocks, but it is not of the magnitude of other studies that allow non-investable micro-caps. Here, the smallest decile by market capitalization had the highest compound return between December 31, 1926 and December 31, 2009 and the largest two deciles had the lowest compound returns, but the amounts are not huge: The tenth decile had the highest return at 10.95 percent per year whereas the first decile (largest stocks) had the lowest return at 8.82 percent, a difference of 2.13 percent.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why You Should Write Letters to Your Kids as They Grow

“Letters are among the most significant memorial a person can leave behind them.”

~Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

I’ve always believed in the written word. Having to put your thoughts in writing helps you understand if you clearly understand what—and how—you want to say something. And if you keep written journals, there is simply no way to let hindsight bias take over, for there, in your own hand, is what you thought about something at the time, with revisions through selective memory impossible.

Writing clarifies. It illuminates. It helps you follow your own growth (or decay) in the way you look at the world and how your ideas have changed—or remained the same—over the course of your life. As someone with boxes and boxes of old journals, If I want to know what 21-year-old me thought about something, all I must do is pull out that journal and read. Sometimes I’m amazed by how much my views have changed—often dramatically—as I have made my way through life.

Yet equally telling is how little some of my foundational beliefs have changed. For the most part, I find that that, if anything, they have become stronger, better articulated, and better supported. I’m a big believer in reading as much as you can that takes the other side of what you think. We’re all subject to confirmation bias, and a great habit to build is to always search out beliefs that counter your own. If they make you change your mind, as has happened with me, then your original belief really wasn’t that sound to begin with, so, by always challenging yourself, you make your thinking stronger and more truly reasoned.

But the reason I’m writing today is to urge every parent reading this to get in the habit of writing your children a series of letters so that they too can understand you, and, with luck, themselves better. Having to articulate thoughts in a letter allows you and your children time to reflect on things in a way that is often difficult in the day-to-day events of your lives together. It’s something that I always wish my dad had done, as we had a rather difficult time understanding each other and I think a series of letters from him would have helped me understand him much better than I ultimately did.

Ideally, you should start as soon as you can and continue to write over the years. I started when my son, Patrick, was 7 days old and continued until my last child turned 21. As each child hit 21, my wife—the true marvel in the parenting hall of fame--would select photos and publish the letters in book form for each of my kids. The last letter of each book was written specifically to the child the book was for, but otherwise all the letters were for all my kids.

Below is the first letter I wrote which I hope spurs you on to do this for your kids. Rarely are things 100 percent win/win, but in the case of letters for your kids, that’s the reward for taking the time as your kids grow to have a conversation with the adult they will become.

April 22, 1985

Dear kids,

Firsts are exciting and somewhat perplexing. This is the first entry in a book I’m going to keep for you; its direction not yet known to me. Thus, the thought of giving you something created over the years excites me, but I am also perplexed about what I really want to write here.

I know that I don’t want this to be a diary, detailing the days, for although we already love you we know that a diary of when you eat and sleep wouldn’t be exciting reading. In some ways, I hope to be able to say all the things fathers want their children to know, yet so many times forget, or neglect to tell them.

If nothing else, you will see how I changed, from a 24-year-old brand new father, to one who has watched you grow up, and, with luck, grown up myself.

Most of all, you may be able to know both me and yourself better through this collection of “letters” and we must all strive to understand ourselves and those we love, for through our understanding and experience comes the wisdom that no one person can teach another, no school can transmit it. It must come from within, from learning, from logic and experience. If I could, I would describe it for you; I can’t. Perhaps you will agree when you are older.

I also want to tell you about me, my life, my thoughts, perhaps you can gain some understanding of yourself through understanding me. If I was going to describe my own impulses in a paragraph, it would be advice to you as well, so here, in Lao Tzu’s words, it is:

“He who knows much about others may be learned, but he who understands himself is more intelligent. He who controls others may be powerful, but he who controls and has mastered himself is mightier still. He who receives his happiness from others may be rich, but he whose contentment is self-willed has inexhaustible wealth. He who occupies a place provided for him by others may live a long life, but he who dwells in his own self-constituted place, even though he decays, is eternal.”

That bit of wisdom really embodies many of my goals, and many of my beliefs.

You will always be only as good, only as happy, only as successful as you perceive yourself to be. Happiness springs from within, never from without. Virtue too; honor; and love. All the things that make a life worth living. Thus, if you are unhappy, don’t look outside yourself for causes, the reside within; likewise, if, like me, you are happy, understand the source within your soul.

Love,

Dad

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Arbitrage Human Nature

People want to believe the present is different than the past. Markets are now computerized, high-frequency and block traders dominate, the individual investor is gone and, in his place, sit a plethora of huge mutual and hedge funds to which he has given his money. Many have simply given up trying to earn alpha in the market and have given their money to index funds. Some people think these masters of money make decisions differently and believe that looking at how a strategy performed in the 1950′s or 1960′s offers little insight into how it will perform in the future.

But while we humans passionately believe that our own current circumstances are somehow unique, not much has really changed since the inarguably brilliant Isaac Newton lost a fortune in the South Sea Trading Company bubble of 1720. Newton lamented that he could “calculate the motions of heavenly bodies but not the madness of men.” Herein lays the key to why basing investment decisions on long-term results is vital: the price of a stock is still determined by people. If you chart price of the South Sea company’s stratospheric rise and then compare it with the NASDAQ in the 1990′s, you’ll see they are virtually identical. As long as people let fear, greed, hope and ignorance cloud their judgment, they will continue to misprice stocks and provide opportunities to those who rigorously use simple, time-tested strategies to pick stocks. Unless you believe that human nature will fundamentally change soon, using long-term studies of which stocks do well and which do poorly lets you to arbitrage human nature. Newton lost his money because he let himself get caught up in the hoopla of the moment and invested in a colorful story rather than the dull facts. Names change. Industries change. Styles come in and out of fashion, but the underlying characteristics that identify a good or bad investment remain the same.

Each era has its own group of stocks that people flock to, usually those with the most intoxicating story. Investors of the twenties sent the Dow Jones Industrial Average up 497% between 1921 and 1929, buying into the “new era” industries such as radio and movie companies. In 1928 alone, gullible investors sent Radio Corporation from $85 to $420 per share, all based on the hope that this new marvel would revolutionize the world. In that same year, speculators sent Warner Brothers Corporation up 962 percent—from $13 to $138—based on their excitement about talking pictures and a new Al Jolson contract. The 1950s saw a similar fascination in new technologies, with Texas Instruments soaring from $16 to $194 between 1957 and 1959, with other companies like Haloid-Xerox, Fairchild Camera, Polaroid and IBM being beneficiaries of the speculative fever. Closer to home, remember all the dot.coms of the late 1990s that soared on little more than a PowerPoint presentation and a lot of sizzle? And, of course, now we have Bitcoin…

The point is simple. Far from being an anomaly, the euphoria of the late 20’s; 60’s and 90’s were predictable ends to a long bull markets, where the silliest investment strategies often do extraordinarily well, only to go on to crash and burn. A long view of returns is essential because only the fullness of time uncovers basic relationships that short-term gyrations conceal. It also lets us analyze how the market responds to a large number of events, such as inflation, stock market crashes, stagflation, recessions, wars and new discoveries. From the past the future flows. History never repeats exactly, but the same types of events continue to occur. Investors who had taken this essential message to heart in the last speculative bubble were the ones least hurt in the aftermath. They understand that today’s events and news are mostly noise, and that only longer periods of time deliver the much more accurate signal. As Pericles said, they “wait for the wisest of all counselors, time.”

The same is true after devastating bear markets. Investors behave as irrationally after protracted bear markets as they do after market manias, leaving the equity markets in droves, usually at or near the market’s bottom. By the time they gather enough courage to venture back into equities, a good portion of the recovery has often already happened. Investors who remained on the sidelines in 2009 left between 50 and 75 percent of gains on the table, making it very difficult for them to catch up with the market.

We are always trying to second guess the market, but the facts are clear—there are no market timers on the Forbes 500 list of the richest people, whereas there are many, many investors.

0 notes

Text

Getting the Most Out of Your Equity Investments

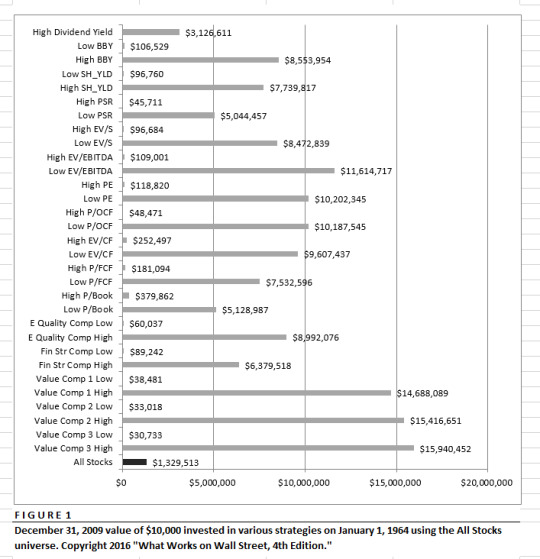

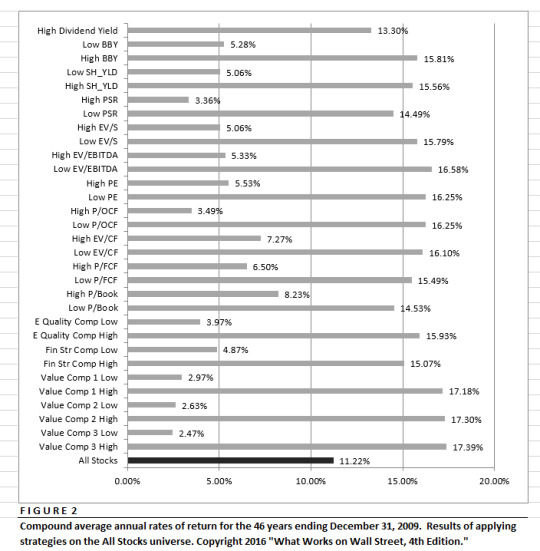

As we approach 2018, I thought this final chapter from the 4th edition of What works on Wall Street might be a helpful frame of reference for equity investors.

“To think is easy. To act is difficult. To act as one thinks is the most difficult of all.”

--Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Investors can learn much from the Taoist concept of Wu Wei. Taoism is one of the three schools of Chinese philosophy that have guided thinkers for thousands of years. Literally, Wu Wei means “to act without action” but in spirit means to let things occur as they are meant to occur. Don’t try to put square pegs into round holes. Understand the essence of a circle and use it as nature intended. The closest western equivalent is Wittgenstein’s maxim: “Don’t look for the meaning: Look for the use!”

For investors, this means letting good strategies work. Don’t second guess them. Don’t try to outsmart them. Don’t abandon them because they’re experiencing a rough patch. Understand the nature of what you’re using and let it work. This is the hardest assignment of all. It’s virtually impossible not to insert our ego or emotions into decisions, yet it is only by being dispassionate that you can beat the market over time.

We’ve lived through the most tumultuous market environments since the 1920s and 1930s since I originally published this book in 1996. A stock market bubble between 1996 and March 2000—the likes of which we had not seen since the late 1960s and before that the roaring 1920s—led many investors to throw out the investing rule book. The more insanely overvalued a company, the more it soared. Everyone talked of “the new economy” and how it really was different this time. Sticking with time-tested investment strategies during the stock market orgy was close to impossible. Month in, month out you had to stand on the sidelines, watching your reasonably-priced stocks do nothing while the over-priced “story” stocks soared. And, as often happens with stock market bubbles, just as the last sane investors capitulated and learned to love the stocks with the craziest valuations, along came the reckoning—all the previously gravity-defying stocks came crashing back to earth. Fortunes were lost and millions of investors lost their faith in the long-term potential of stocks. What’s worse is that after recovering from the bear market of 2000-2003, a new bubble appeared in real estate markets and the debt used to finance them. This new bubble popped in any even more destructive fashion than that of the dot.com stocks earlier in the decade and brought worldwide markets close to the brink of collapse, ushering in the worst bear market for stocks since the Great Depression. Investor’s faith in equity markets was almost completely destroyed by the great market crash of 2007-2009. The S&P 500’s loss of 37 percent in 2008 was second only to 1931, where it dropped by 43 percent. People were literally hoarding cash, terrified to make any investment in the stock market. And much as the bubble years gave birth to the idea that things really were different than in the past and we had emerged with a “new economy”, the bust years also gave birth to the concept of “the new normal.” To its advocates, the new normal meant that returns would be permanently lower going forward than they had been historically and there was really nothing that we could do about it. Money poured out of equities into bonds with investors desperate to avoid risk of any kind. The September 2010 issue of Institutional Investor had a cover story entitled “Paradise Lost: Why Fallen Markets Will Never be the Same”, in which the authors argue that “the financial crisis has discredited free-market capitalism and given its state-driven counterpart a boost.” Yet we are forever fighting yesterday’s battle without paying attention to what we can learn from historical events.

In markets moving from extreme speculation to extreme despair, believing in Ockham’s razor—that the simplest theory is usually the best—is almost impossible. We love to make the simple complex, follow the crowd, get seduced by some hot “story” stock, let our emotions dictate decisions, buy and sell on tips and hunches and approach each investment decision on a case-by-case basis, with no underlying consistency or strategy. On the flip side, when equity returns are horrible over a long period of time, we are far too willing to assume that stocks will never generate returns comparable to those of the past and abandon them in favor of less risky assets like bond and money market funds. Even fourteen years after this book was first published—showing decade upon decade of the results of all the various types of strategies—people were more than willing to throw it all out the window because of short-term events, be they good or bad. No wonder the S&P 500 beats 70 percent of traditionally-managed mutual funds over the long-term!

A Taoist story is illuminating: One day a man was standing at the edge of a pool at the bottom of a huge waterfall when he saw an old man being tossed about in the turbulent water. He ran to rescue him, but before he got there the old man had climbed out onto the bank and was walking alone, singing to himself. The man was astonished and rushed up to the old man, questioning him about the secret of his survival. The old man said that it was nothing special. “I began to learn while very young, and grew up practicing it. Now, I’m certain of success. I go down with the water and come up with the water. I follow it and forget myself. The only reason I survive is because I don’t struggle against the water’s superior power.”

The market is like the water, overpowering all who struggle against it and giving those who work with it a wonderful ride. But swimming lessons are in order. You can’t just jump in, you need guidelines. Our study of the last 84 years with the CRSP dataset and 46 years with the COMPUSTAT suggests that to do well in the market, you must do the following:

Always Use Strategies

You’ll get nowhere buying stocks just because they have a great story. Usually, these are the very companies that have been the worst performers over the full time period of our study. They’re the stocks everyone talks about and wants to own. They often have sky-high price-to-earnings, price-to-book and price-to-sales ratios. They’re very appealing in the short-term, but deadly over the long haul. You must avoid them. Always think in terms of overall strategies and not individual stocks. One company’s data is meaningless, yet can be very convincing. Conversely, don’t avoid the market or a stock simply because things have been bad over the short-term. Few investors could see the compelling valuation of the overall stock market in March 2009, yet it was at this time that stocks were a screaming buy and about to embark on a huge rally. If you had a simple rebalance strategy in place at the time which allocated between stocks and other investments, the strategy would have forced you to buy more stocks. But as Goethe’s quote at the beginning of this chapter makes plain, acting is hard, and acting in line with what you think is almost impossible. If you can’t use strategies and are inexorably drawn to the stock of the day, your returns suffer horribly in the long run. Remind yourself of what happens to these stocks by looking at charts of all the dot.com high flyers between 1998 and 2002 and the tables and charts for how value stocks came soaring back after the stock market bubble burst in 2000. If, try as you might, you can’t stick to a strategy, put the majority of your money in an index fund and treat the small amount you invest in story stocks as an entertainment expense.

Ignore the Short-term

Investors who look only at how a strategy or the overall market has performed recently can be seriously misled and end up either ignoring a great long-term strategy that has recently underperformed or piling into a mediocre strategy that has recently been on fire. Over the last 15 years, I cannot count the number of times investors have gotten extremely excited about our strategies as they were doing well relative to their benchmark and the same number of times that investors became despondent about short-term underperformance. Tragically, investors seem hardwired to inordinately focus on very short periods of time, often completely ignoring how the strategy has done over long periods of time. As investors, all of our information about returns is focused on extremely short periods of time. Witness everyone falling all over themselves to explain why the stock market has gone up or down in a single day! What’s funny is that over very short periods of time, the stock market is relatively impossible to forecast, yet when you extend your horizon, the market becomes far more understandable. As I mentioned in the introduction, if you look at the 50 worst ten year performances for the stock market, there is not a single instance where over the next ten years the stock market failed to go up.

The point is that at some time in the future any of the strategies in this book will underperform the market, and it is only those investors who can keep their focus on the very long-term results who will be able to stick with them and reap the rewards of a long-term commitment. You should always guard against letting what the market is doing today influence the investments decisions you make. One way to do this is to focus on the rolling batting average of how your portfolio is performing versus its benchmark. Much like we focus on the rolling base rates for all of the stock selection strategies we have tested in this book, you can do the same for your portfolios performance versus its benchmark. When you look only at how your investment portfolio has performed for the last quarter, year, and three and five year period, you are simply looking at a single snapshot of how you’ve done. Now, this might make you very happy if you’ve done exceedingly well for that particular period but it also might make you want to abandon your strategy if you’ve done poorly relative to other strategies available. In both cases, I would argue that you are potentially misled by only looking at a snapshot. What if it is December 31st, 1999 when you take a look at this snapshot? For an investor who had loaded up on pricey dot.com and tech stocks five years earlier looking at the snapshot and he or she will think they are a genius—my God, I will be able to retire in a few years if I keep growing my portfolio at this rate! Or how about an investor who had kept their portfolio devoted to small-cap stocks and large-cap value fare? They might look at how they’ve done and wince about the relative lack of great returns in their portfolio and be tempted to follow the same strategy as the first investor with a tech and dot.com heavy portfolio. By looking at the snapshot at that point in time and extrapolating it into the future, both investors would have been seriously misled. The tech-heavy portfolio went on to crash and burn just as the small-cap and value portfolio began to soar.

By focusing on how your portfolio is doing against a benchmark on rolling periods, you will get a much better sense for how you are continuously doing against the market and will be much more likely to be willing to stick with a strategy that may be underperforming recently but has an outstanding win rate versus the market over all rolling periods. It gives you continuous feedback that allows you to take the hills and valleys with greater restraint than if you simply looked at one point in time. It also lets you put recent performance into the historical context of the strategy—if you’re relative performance is down but still very much in line with what the strategy has done historically, you will probably be more able to stay the course.

Finally, this advice is equally useful after sharp draw downs for stocks. In March of 2009 I wrote a commentary for Yahoo Finance that was entitled “A Generational Opportunity” in which I argued that many investors were facing a once in a lifetime gift to purchase equities at valuations that we hadn’t seen since the early 1980s. I urged middle-aged investors to increase the equity allocation of their portfolio to 70 percent to take advantage of the fear that permeated the markets and for the most part the response was silence. People were so shell-shocked by what had happened over the previous 15 months that no amount of data would move them to take advantage of the situation. That’s why ignoring the short term may be both the hardest and best thing you can do for the overall health of your portfolio.

Use Only Strategies Proven Over the Long-Term

Always focus on strategies whose effectiveness is proven over a variety of market environments. The more time periods you can analyze, the better your odds of finding a strategy that has withstood a variety of stock market environments. Buying stocks with high price-to-book ratios appeared to work for as long as 15 years, but the fullness of time proves that it is not effective. Many years of data help you understand the peaks and valleys of a strategy. What’s more, sometimes a strategy might make intuitive sense, like buying stocks that have the greatest annual gain in sales, yet a review of the data tells us that, in the long-run, this is a losing strategy, probably because investors get so excited by those huge annual sales increases that they price the stocks to perfection, which is rarely achieved. Attempting to use strategies that have not withstood the test of time will lead to great disappointment. Stocks change. Industries change. But the underlying reasons certain stocks are good investments remain the same. Only the fullness of time reveals which are the most sound. Remember how alluring all the dot.com stocks were in the late 1990s? Don’t let the investment mania de jour suck you in—insist on long-term data that supports your investment philosophy. Remember that there will always be current market fads. In the 1990s it was internet and technology stocks, tomorrow it might be nanotechnology or emerging markets, but all bubbles get popped.

Dig Deep

If you’re a professional investor, make certain to test any strategy over as much time and as many seasons as possible. Look for the worst-case scenario, the time it took to recover from that loss and how consistent it was against its relevant benchmark. Note the largest downside deviation it had against the benchmark and be very wary of any strategy that has a wide downside deviation from it. Most investors can’t stomach being far behind the benchmark for long.

If you’re an individual investor, insist that your advisor conduct such a study on your behalf, or do it yourself. There are now many websites where you can do this research. With all the tools now available to individual investors, there is simply no excuse for not doing your homework. A wonderful resource for individual investors is the American Association of Individual Investors. Their website (www.aaii.com) is chockablock full of helpful ideas as well as an entire section devoted to stock screening. Check the links at www.whatworksonwallstreet.com for any new sites that might appear to aid you in your research.

Invest Consistently

Consistency is the hallmark of great investors, separating them from everyone else. If you use even a mediocre strategy consistently, you’ll beat almost all investors who jump in and out of the market, change tactics in midstream, and forever second-guess their decisions. Look at the S&P 500. We’ve shown that it is a simple strategy that buys large capitalization stocks. Yet this one-factor, rather mediocre strategy still manages to beat 70 percent of all actively managed funds because it never leaves its strategy. Realistically consider your risk tolerance, plan your path and then stick to it. You may have fewer stories to tell at parties, but you’ll be among the most successful long-term investors. Successful investing isn’t alchemy, it’s a simple matter of consistently using time-tested strategies and letting compounding work its magic.

Always Bet With the Base Rate

Base rates are boring, dull and very worthwhile. Knowing how often and by how much a strategy beats the market is among the most useful information available to investors, yet few take advantage of it. Base rates are essentially the odds of beating the market over the time period you plan to invest. If you have a ten-year time horizon and understand base rates, you’ll see that picking stocks with the highest multiples of earnings, cash flow, sales or lowest value composite score has very bad odds. If you pay attention to the odds, you can put them on your side. You now have the numbers. Use them. Don’t settle for strategies that may have done very well recently but have poor overall batting averages. Chances are you’ll be getting in just as those long-term base rates are getting ready to reassert themselves.

Never Use the Riskiest Strategies

There is no point in using the riskiest strategies. They will sap your will and you will undoubtedly abandon them, usually at their low. Given the number of highly effective strategies, always concentrate on those with the highest risk-adjusted returns.

Always Use More Than One Strategy

Unless you’re near retirement and investing only in low risk strategies, always diversify your portfolio by investing in several strategies. How much you allocate to each is a function of risk tolerance, but you should always have some growth and some value guarding you from the inevitable swings of fashion on Wall Street. Once you have exposure to both styles of investing, make sure you have exposure to the various market capitalizations as well. A simple rule of thumb for investors with ten years or more to go until they need the money is to use the market’s weights as guidelines. Currently, 75 percent of the market is large-cap and 25 percent is small- and mid-cap. That’s a good starting point for the average investor. Unite strategies so your portfolio can do much better than the overall market without taking more risk. Indeed, while this book only covers stocks that trade in the United States, with a reasonable number of them being American depository receipts of Foreign-domiciled companies that offer shares to U.S. investors, you might think about having your portfolio aligned in a similar fashion to the MSCI All World Index. Currently, the U.S. makes up 35 percent of that index, with Japan, the United Kingdom. France and Canada rounding out the top five. If you include the next five countries by market capitalization, Hong Kong, Germany, Australia, Switzerland and Brazil, you would cover 74 percent of the total market capitalization in the world. The point is, these strategies work outside the United States as well, and a well diversified portfolio should reflect this. We have run tests similar to those in this book on the MSCI dataset that begins in 1970 and found that, for the most part, these strategies work equally well in foreign markets.

Additionally, you should have a plan for your entire portfolio, not just the equity portion. One of the simplest and most effective strategies for your entire portfolio is to rebalance your allocations to various styles and asset classes back to your target allocation at least once a year. If you are working with a financial advisor, he or she is probably already doing this for you, but if not, figure out what makes the most sense for you and then make sure that you follow your allocation. What this effectively does is force you to buy more of an investment style or an asset class when it has done poorly and take money away from styles and asset classes that have done well. It would have served you extraordinarily well near the bear market bottoms of the last decade, as it would have forced you to move money from fixed income into equities at a time when most investors were fleeing the equity market and allowed you to take advantage of the big move up from the market bottom. But it also would have served you well during the last market boom, as it would have had you trim equity allocations and put additional money in fixed income and other assets. It’s important to have a strategy for your entire portfolio.

Use Multifactor Models

The single factor models show the market rewards certain characteristics while punishing others. Yet you’re much better off using several factors to build your portfolios. Returns are higher and risk is lower. You should always make a stock pass several hurdles before investing in it. The only exceptions to this rule are our Composited factors like the Composited Value Factor, the Composited Earnings Quality and so forth. These are essentially multifactor models as they include several factors and require a good score on each for a stock to rise to the top.

Insist On Consistency

If you don’t have the time to build your own portfolios and prefer investing in mutual funds or separately managed accounts, buy only those that stress consistency of style. Many managers follow a hit-or-miss, intuitive method of stock selection. They have no mechanism to reign in their emotions or insure that their good ideas work. All too often their picks are based on hope rather than experience. You have no way to really know exactly how they are managing your money, or if their past performance is due to a hot hand unguided by a coherent underlying strategy.

Don’t bet with them. Buy one of the many funds based on solid, rigorous strategies. If your fund doesn’t clearly define its investment style, insist that they do. You should expect nothing less.

The Stock Market Is Not Random

Finally, the data proves the stock market takes purposeful strides. Far from chaotic, random movement, the market consistently rewards specific strategies while punishing others. And these purposeful strides have continued to persist well after they were first identified. We now have not only what Ben Graham requested—the historical behavior of securities with defined characteristics—we also have a 14-year period where we’ve witnessed their continued performance in real time. We must let history be our guide, using only those time-tested methods that have proven successful. We know what is valuable and we know what works on Wall Street. All that remains is to act upon this knowledge.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why Selling a Big Position of Puts the Day Before the Crash of ‘87 was a great trade

Tada Viskanta saw a series of tweets I did when reading about the new book, “A first Class Catastrophe” by Diana B. Henriques which chronicles the 1987 crash, the largest one-day crash in U.S. Market history and he urged me to write up my experience at the time. While I have not yet read the book, in my tweets I reminisced about what it felt like to me. I was 27 years old and had been investing—or more properly—speculating in the market since age 21.

At the time, I was using a much different methodology for determining buys and sells then I do now, and I had, for several weeks before the crash, been accumulating a large put position on the OEX, which represented the S&P 100. The OEX and XMI where popular with options traders of that era and had the greatest liquidity for the options tied to them. Going into the crash, I had a larger position in puts than at any other point in my nascent career. I was sweating bullets, as many of them were deeply out of the money and my worry was they would all expire worthless, leaving me with a huge loss.

When I was 27, I already believed in a series of indicators that were mostly accurate, but I also paid great attention to the news and what people were saying about the future direction of the market. I watched as the markets roiled on Friday, October 16th, with the Dow losing more than 4.6% of its value.

I then made what at the time looked like the biggest mistake of my trading career—about a half an hour before the markets close on Friday, reacting to assertions that the market’s drop was way overdone and that we would see a huge snapback on Monday, I sold my entire put position.

Just so it really sinks in, I repeat, on the day before the biggest crash in history, I let my emotional reactions to what I was reading and hearing drive my behavior, and I sold every single put option that I had carefully accumulated over the previous several weeks.

Had I held, I would have made a not so small fortune. But I didn’t. Indeed, I barely broke even on the entire trade. But as I reflected and wrote about in my trading journal, I think that turned out to be the greatest trade in my life.

For that trade sent me down the road that led to where I am today—I concluded that my emotions were my worst enemy in the market and that listening to predictions from gurus and other prominent market forecasters was worse than useless, it was destructive. It also opened my eyes to how early reactions by the media to such momentous events are almost always spectacularly wrong. I still have many of the newspapers and Barron’s from that time, as well as news magazines, etc. re-reading them now shows how any early reaction is also primarily based upon emotions and utterly fails to put anything in correct context.

It was the best wakeup call I could have received. I resolved to begin searching for empirically supported investment strategies that withstood the test of time. It got me to understand that if I were to succeed over the long-term, I had to match my investment strategy to my time horizon. If I had 30 or more years to go to achieve my goals, I thought I should find out which strategies performed the best over much longer periods of time and which had the highest base rates of success against their benchmarks.

Most importantly, it cemented in me that while in many areas of life emotions were great, in the world of investing they were your worst enemy. And that only an unwavering discipline, devoid of any emotional override, would win in the end. Over the 30 years since the crash, I have witnessed time and again some of the smartest people in the world undone my making emotional investment decisions based on very short-term events. This will never, ever change. Lest you think that rules-based, quantitative investing can solve this, think again. An analyst from a major Wall Street bank was visiting OSAM after the financial crisis and he noted that over 60% of quants overrode their models during the crisis. Remaining unemotional in my time as a portfolio manager has been one of the hardest things I have done, and yet, well worth it over the longer term. Oddly, it took the agony I felt selling my huge put position the day before the crash to teach me that agony, let alone any other emotion, has no place in implementing a successful investing career.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Successful Active Stock Investing is Hard: Here are Seven Traits that I Believe are Required for Active Investors to Win in the Long Term

Years of experience have taught me that to be a successful active investor requires a very specific set of characteristics, and that many investors attempting to actively manage their portfolios today lack the emotional and personality traits necessary for success.

Investors with passive portfolios—assuming they are adequately and broadly diversified—face only one real point of failure: reacting emotionally to a market selloff and selling their holdings, often near a market bottom.

But investors who use actively managed strategies face two points of failure:

1. Reacting emotionally to a market selloff and liquidating their holdings, usually at the very worst time; and

2. Selling out of an active strategy that is doing worse than its benchmark, often over periods as little as three years.

The second point of failure occurs even if the investor has earned positive returns in the active strategy—let’s say a gain of 10% per year over the last three years versus a benchmark return of 12%. While all investors face the same point of failure when selling during market swoons, only active investors face the second pitfall. What’s more, research has shown that managers who are fired due to a three-year underperformance typically go on to outperform the manager with which the investor replaces them.

Obviously, this second point of failure can destroy long-term results, even if the general market has been performing well. Sadly, I have seen this type of behavior often, leading me to conclude that for many investors, active management will never work because they lack the emotional and philological traits required to succeed.

Now, let’s look at seven traits that I think are necessary to be a successful long-term active investor.

1. Successful Active Investors Have A Long-Term Perspective on Their Investments.

“Having, and sticking to a true long term perspective is the closest you can come to possessing an investing super power.”

~ Tweet from Cliff Asness, Co-Founder AQR Capital Management

Cliff is right, but, sadly, most investors lack this ability. Evolution has programmed us to pay far more attention to what is happening now than to what might happen in ten or twenty years. For our ancient ancestors, that made a great deal of sense. Those who reacted quickly to rustling in a nearby bush—assuming it was a predator who could kill them--ran away and survived, whereas those who didn’t were often killed. Guess whose genes got passed down to us? Of course it was those that ran, even if there was no fatal threat.

Our culture has evolved much more rapidly than our brains, which doesn’t help us keep a long-term perspective on our investments. When you time-weight short-term information for investment decisions, you create a reactionary model, not an anticipatory one.

Many behaviors that hobble making good investment choices seem to be encoded into our genes. In their paper Why do Individuals Exhibit Investment Biases?, researchers Henrik Cronqvist and Stephan Siegel write:

“We find that a long list of investment biases—e.g., the reluctance to realize losses, performance chasing, and the home bias—are human, in the sense that we are born with them. Genetic factors explain up to 45% of these variation in those biases across individuals. We find no evidence that education is a significant moderator of genetic investment behavior.”

Wow! It’s no wonder that the majority of investors succumb to short-term volatility in the market by selling and waiting until markets have been very strong to begin buying, even though more than 30 years of studies have proven this is exactly the wrong thing to do. It’s literally programmed into our genes and is impervious to education. We are also prone to a slew of cogitative biases, from overconfidence in our own abilities to our tendency to overweight things simply based upon how easily they are recalled. And knowing about our biases of judgment—something that has been noted in market research for more than 30 years—hardly eliminates them.

Successful active investing runs contrary to human nature. It’s encoded in our genes to overweight short-term events, to let emotions dictate decisions and to approach investing with no underlying cohesiveness or consistency. Successful active investors do not comply with nature; they defy it. The past, present and future make up their now. It’s not natural to watch others get caught up in spirals of greed and fear, causing booms and panics, and remain unmoved. It’s not natural to remain unemotional when short-term chaos threatens your nest egg. And, leading to my next required trait, it’s not natural to persevere in a rigorous, consistent manner—no matter what the market is doing.

2. Successful Active Investors Value Process over Outcome.

“If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, you don’t know what you’re doing.”

~W. Edwards Deming

The vast majority of investors make investment choices based upon the past performance of a manager or investment strategy. So much so that SEC Rule 156 requires all money managers to include the disclosure that “past performance is not indicative of future results.” It’s ubiquitous--and routinely ignored by both managers and their clients. In keeping with human nature, we just can’t help ourselves when confronted with great or lousy recent performance. “What’s his/her track record?” is probably investors’ most frequently asked question when considering a fund or investment strategy. And, as mentioned above, the vast majority of investors are most concerned with how an investment did over the last one- or three-year period.

Yet successful active investors go further and ask “what’s his or her process in making investment decisions?” Outcomes are important, but it’s much more important to study and understand the underlying process that led to the outcome, be it good or bad. If you only focus on outcomes, you have no idea if the process that generated it is superior or inferior. This leads to performance chasing and relying far too much on recent outcomes to be of any practical use. Indeed, shorter-term performance can be positively misleading.

Look at a simple and intuitive strategy of buying the 50 stocks with the best annual sales gains. Consider this not in the abstract, but in the context of what had happened in the previous five years:

Year Annual Return S&P 500 return

Year one 7.90% 16.48%

Year two 32.20% 12.45%

Year three -5.95% -10.06%

Year four 107.37% 23.98%

Year five 20.37% 11.06%

Five-year

Average Annual

Return 27.34% 10.16%

$10,000 invested in the strategy grew to $33,482, dwarfing the same investment in the S&P 500, which grew to $16,220. The three-year return (which is the metric that almost all investors look at when deciding if they want to invest or not) was even more compelling, with the strategy returning an average annual return of 32.90% compared to just 7.39% for the S&P 500.

Also consider that these returns would not appear in a vacuum—if it was a mutual fund it would probably have a five star Morningstar rating, it would likely be featured in business news stories quite favorably and the long-term “proof” of the last five years would say that this intuitive strategy made a great deal of sense and therefore attract a lot of investors.

Here’s the catch—the returns are for the period from 1964 through 1968, when, much like the late 1990s, speculative stocks soared. Investors without access to the historical results for this investment strategy would not have the perspective that the long term outlook reveals, and thus might have been tempted to invest in this strategy right before it went on to crash and burn. As the data from What Works on Wall Street make plain, over the very long term, this is a horrible strategy that returns less than U.S. T-bills over the long-term.

Had an investor had access to long-term returns, he or she would have seen that buying stocks based just on their annual growth of sales was a horrible way to invest—the strategy returned just 3.88 percent per year between 1964 and 2009! $10,000 invested in the 50 stocks from All Stocks with the best annual sales growth grew to just $57,631 at the end of 2009, whereas the same $10,000 invested in U.S. T-Bills compounded at 5.57 percent per year, turning $10,0000 into $120,778. In contrast, if the investor had simply put the money in an index like the S&P 500, the $10,000 would have earned 9.46 percent per year, with the $10,000 growing to $639,144! What the investor would have missed during the phase of exciting performance for this strategy is that valuation matters, and it matters a lot. What investors missed was that these types of stocks usually are very expensive, and very expensive stocks rarely make good on the promise of their sky-high valuations.

Thus, when evaluating an underlying process, it’s important to decide if it makes sense. The best way to do that is to look at how the process has fared over long periods of time. This allows you to better estimate whether the short-term results are due to luck or skill. We like to look at strategies rolling base rates—this creates a “movie” as opposed to a “snapshot” of how strategies perform in a variety of market environments.

Lest you think you can only do this with quantitative strategies that can be back tested, consider Warren Buffett’s results at Berkshire Hathaway. If you were making a choice about whether to invest in Berkshire stock using short-term results at the end of 1999, you probably would have passed, as over the previous three years, it underperformed the S&P 500 by 7.6% per year, and over the previous five years, by 3.76% per year. Indeed, your decision would have been reinforced by the news stories circulating that Buffett’s simple process no longer worked in the tech-dominated “new normal” for the stock market.

But if you checked on Buffett’s process, you would find that nothing had changed and that he still followed the stringent criteria he always had, generally looking for stocks with:

1. Recognizable brands with a wide moat;

2. Simple, easy to understand products and services;

3. Consistent, solid earnings over a long time period;

4. Low and manageable debt, and

5. Good ROE and other solid ratios.

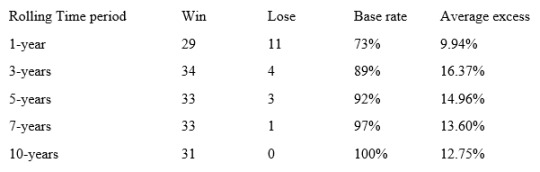

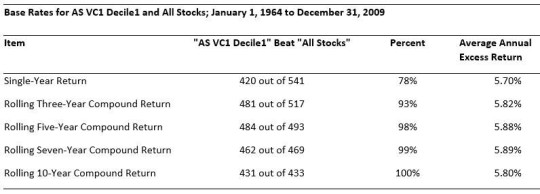

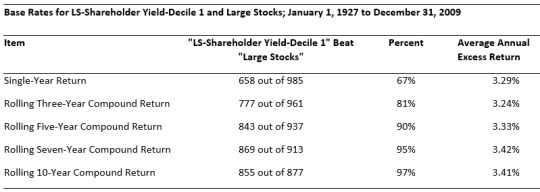

These seem like sensible ways to buy stocks, and Buffett showed no signs of deviating from the strategy—he was (and is) patient and persistent, sticking with a proven strategy even when it isn’t working in the short-term. Now take a look at Buffett’s base rates from 1977 through 2016, Using Berkshire Class A stock:

These base rates are very similar to investing in the 10% of stocks that are cheapest based upon our value composite 1 from What Works on Wall Street, which ranks stocks on:

1. Price-to-book;

2. PE;

3. Price-to-sales;

4. EBITDA-to-enterprise value; and

5. Price-to-cash flow.

This process always focuses on the cheapest stocks in the universe and makes a great deal of intuitive sense, which is backed up by the process and its performance over time.

3. Successful Active Investors Generally Ignore Forecasts and Predictions.

“I don’t let people do projections for me because I don’t like throwing up on the desk.”

~Charlie Munger

“I have no use whatsoever for projections or forecasts. They create an illusion of apparent precision. The more meticulous they are, the more concerned you should be.”

~Warren Buffett

You can’t turn on business TV or read all of the various business news outlets or even talk with other investors without being bombarded with both short- and long-term forecasts and predictions. Against all the evidence, forecasts and predictions about what might happen in the future are intuitively attractive to us, since we are desperate to have a narrative about how the future might unfold. As I mentioned above, we tend to extrapolate what has happened recently well into the future, which almost never works. We’ll explore the results of this in a minute, but for now, consider that since we literally hear or read so many forecasts about markets, stocks, commodity prices, etc. that to follow up on the efficacy of each would be a full-time job. Lucky for us, others have done this job for us, and the results are grim. In a post at his website The Investor’s Field Guide, my son and fellow OSAM portfolio manager, Patrick O’Shaughnessy, highlighted a study that showed:

“The CXO Advisory group gathered 6,582 (investment) predictions from 68 different investing gurus made between 1998 and 2012, and tracked the results of those predictions. There were some very well-known names in the sample, but the average guru accuracy was just 47%–worse than a coin toss. Of the 68 gurus, 42 had accuracy scores below 50%.”

In his book Contrarian Investment Strategies: The Psychological Edge, money manager and author David Dreman looked at the accuracy of analysts’ and economists’ earnings growth estimates for the S&P 500 between 1988 and 2006. Dreman found that the average annual percentage error was 81% for analysts and 53% for economists! In other words, you might as well have bet on a monkey flipping coins.

People tend to take recent events and forecast similar returns into the future. Dreman nicely captures the results by looking at large international conferences of institutional investors where hundreds of delegates were polled about what stocks they thought would do well in the next year. Starting in 1968 and continuing through 1999, Dreman found that the stocks mentioned as favorites and expected to perform well tended to significantly underperform the market, and in many instances the stocks selected ended up in the stock market’s rogue’s gallery—for example, the top pick in 1999 was Enron, and we all know what happened there: one of the largest bankruptcies in corporate history. Least it seem like he was cherry-picking, Dreman looked at 52 surveys of how the favorite stocks of large numbers of professional investors fared between 1929 and 1980, with 18 studies including five or more stocks that experts picked as their favorites. The results? The 18 portfolios underperformed the market on 16 occasions. As Dreman dryly notes: “This meant, in effect, that when a client received professional advice about those stocks, they would underperform the market almost nine times out of ten.”

If you think this is outdated, here are some more famously wrong forecasts, as well as the results of an August, 2000 Fortune Magazine article called “10 Stocks To Last The Decade: A few trends that will likely shape the next ten years. Here’s a buy-and-forget portfolio to capitalize on them.” The results? As of December 31st, 2016 the 10 (or 8, since Nortel and Enron went bankrupt) were down 27%, versus a gain for the S&P 500 of 116%.

Finally, many studies have shown that this is true in almost all forecasts, be they about stock prices, patients needing medical treatment, college admissions offices trying to pick who to admit--and virtually every other industry where professionals were making predictions and forecasts. For more on this, check out Chapter Two of my book, What Works on Wall Street.

4. Successful Active Investors are Patient and Persistent.

“Nothing in this world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not: nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with great talent. Genius will not: unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not: the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.”

~Calvin Coolidge

In addition to having a well thought out process, great active investors are patient and persistent. Warren Buffett, Ben Graham, Peter Lynch, John Neff and Joel Greenblatt are all great investors, and while they have very different ways of looking at the stock market, they all share a common disposition—they are patient and persistent. In 1999, numerous articles and TV features suggested that while Warren Buffett might have been great in the old economy, he was well past his prime and was out of step with the “new” market reality. Buffett’s response? He noted that nothing had changed and that he would stand pat with the process that had served him so well for so long.

The same could be said for every investor on this list. John Neff, a great value investor who helmed Vanguard’s Windsor fund and over his 31 year tenure beat the S&P 500 by 3.1% per year. In the early 1990’s, I remember the cover of Institutional Investor magazine showing a man inside an hourglass where the sand had nearly dropped through to the other side with the question: “Is value investing dead?” Neff, who favored stocks with low PE ratios and high dividend yields and good return on equity and who had therefore had been underperforming over the short-term, did the same as Buffett, he patiently stuck with his process focusing on cheap stocks with superior yields and high ROE. He went on to deliver great returns for his investors.

The point is clear: successful active investors are not simply defined by their process, as many have very different approaches and processes that they follow, but rather by their diligence and persistence in sticking with their strategies even when they are underperforming their benchmarks. But all of these investors are also defined by the clarity of their process.

John P. Reese and Jack M. Forehand wrote a book called The Guru Investor: How To Beat The Market Using History’s Best Investment Strategies, in which they methodically create checklists investors can follow to emulate their favorite manager. Now, while their interpretation of the manager’s criteria is open to debate, they do a good job of creating checklists for the investors they attempt to duplicate, usually using either books or statements from the manager to generate their criteria. They also maintain a website, www.validea.com, detailing the performance and current stock picks from each of the manager’s they follow. For example, much like the list of criteria already covered for Buffett, here’s their process to emulate Ben Graham:

1. No technology companies, company must have high sales;

2. Current ratio of at least 2.0;

3. Long-term debt does not exceed net current assets;

4. Steady EPS growth over the past decade;

5. 3-year average PE is less than 15;

6. Price-to-book times PE is less than 22;

7. Continuous dividend payments.

According to their website, since 2003, applying these criteria to select stocks has returned a cumulative gain of 377%, outperforming the market by 248%! You can see how other managers performed at their website. Note, they subtly anchor you on the long-term by presenting the cumulative return over the last 13 years, thus reinforcing the idea that you should only judge active performance over very long periods of time.

Had you only been looking at the recent performance for the strategy, you would have been led to a very different conclusion—in 2014, the strategy lost 22.9% versus a gain of 11.4% for the S&P 500 and in 2015 it also lost 20.4% versus a slight loss of 0.7% for the S&P 500. Had you started using the strategy at the start of 2014, your account would show a cumulative loss of 39% at the end of 2015 versus a gain of 10.62% for the S&P 500--do you think you would have had the patience, persistence and emotional fortitude to stick with it? For the vast majority, the answer is no. For successful active investors, the answer is yes. Patience and persistence would have paid off in 2016, with a gain of 20% versus a gain of 9.5% for the S&P 500. More importantly, keeping the long-term track record in mind would have immensely helped an active manager or investor to stay the course.

5. Successful Active Investors Have a Strong Mental Attitude.

“Nothing can stop the man with the right mental attitude from achieving his goal; nothing on earth can help the man with the wrong mental attitude.”

~Thomas Jefferson

Ben Graham believed that great investors are made, not born. It takes constant study, learning from both your own experience and that of others to create habits that lead to success. I believe that one of the habits that is not innate but learned is a strong mental attitude. I think that most successful active managers not only have strong mental attitudes, but many border on stoicism. Stoics taught that emotions resulted in errors of judgment and they thought that the best indication of someone’s philosophy was not what a person said, but how they behaved. In the words of Epictetus, “It’s not what happens to you, but how you react that matters.”

Successful active investors understand, as Napoleon Hill stated, “The only thing you control is your mind.” Practically, this means that you do not base your actions, feelings, emotions and thoughts on external events—good or bad—or on what other people are doing or saying, none of which are in your control, but rather on your own actions, beliefs and habits, all of which are in your control.

Successful active investors do not blame others or events; they do not shirk from their personal responsibility for how things turn out, but rather continually focus on their process and trying to improve it. They learn from every lesson, be it good or bad, and continually strive to incorporate that learning into their process. Above all, they understand that you must control your emotions rather than let them control you.

They understand, as Shakespeare famously said, “there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Events very much depend upon how you interpret them. What might cause one person to react emotionally to something is treated as a learning experience by someone with a strong mental attitude. I think that this is a disposition that is learned and rarely innate. It is very helpful on the journey to becoming a successful active manager to keep a journal of how you reacted to various events and outcomes. This allows you to learn if there is a common thread that keeps you from succeeding. If so, you can then actively work to replace those behaviors.

By doing so, you reinforce the belief that the only one controlling your mind is you, which strengthens the synaptic connections in your brain that allow you to make this type of thinking more natural. Once accomplished, your thought patterns and mental attitudes become vastly more useful than reacting from base emotions such as fear, greed, envy and hope. Once habituated, this mindset frees you to persistently follow your process, even when it is not working in the short-term. Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “To map out a course of action and follow it to the end requires courage.” And, I would add, a strong mental attitude.

6. Successful Active Investors Think in Terms of Probabilities

“You don’t want to believe in luck, you want to believe in odds.”

~Charlie Munger

We are deterministic thinkers living in a probabilistic world. We crave certainty about how things will unfold. This is precisely why we fall for predictions and forecasts. Yet, even in the most prosaic of circumstances, nothing in the stock market—or in life—is 100% certain. But many people confuse possibility with probability and the two are almost exact opposites. Think of Jim Carrey’s “Dumb and Dumber” character Lloyd Christmas reacting to the unobtainable Mary Swanson’s rejection of his romantic advances; she told him his chances were “like one out of a million” and he responded: “So you’re telling me there’s a chance. YEAH!” Poor Lloyd mistook possibility with probability. And didn’t understand that the probability of he and Mary hooking up was virtually zero.