Photo

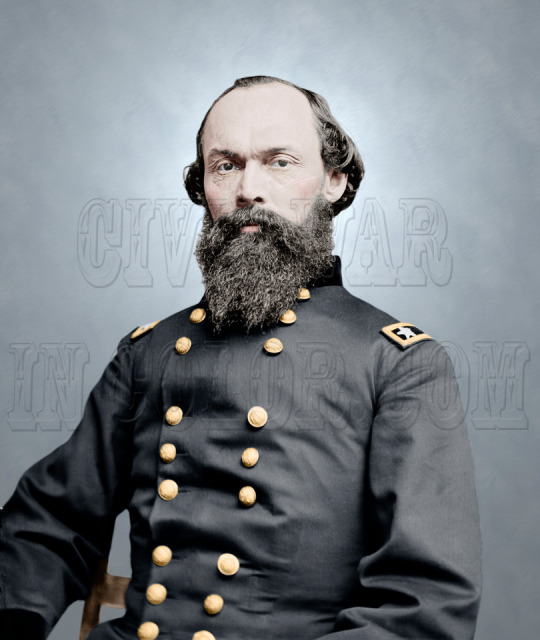

U.S. Gen. Gordan Granger

“Men and women screamed, ‘We’s free! We’s free!’” – Juneteenth celebrants; wharves, Galveston, TX

In June of 1865, Texas was in chaos. Texas had never been conquered during the War. It had recently been an independent Country. The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, would not be ratified until December 6, 1865. More to the point, the economy depended on slave labor. Newspapers speculated that a form of forced black labor would continue.

The Federal government was concerned about being overwhelmed by newly freed slaves flocking to U.S. outposts. Furthermore, in violation of the Monroe Doctrine, France had installed a puppet emperor in April of 1864. Former confederates were contemplating exile in Mexico to fight for Emperor Maximilian.

On June 17, 1865, U.S. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas as the commander of the newly formed District of Texas. Today, Granger is best known for coming to US Gen George “Rock of Chickamauga” Thomas’s aid during the Battle of Chickamauga, GA .

To settle the slavery issue, it would have been expedient to read Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Instead Granger composed General Order No. 3, read from the balcony of Ashton Villa on June 19th.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

The Order was not graciously received by all. It was reported that a slave patrol whipped one hundred celebrants. A jubilant newly freed slave was told by his former master that if he jumped again, “I will shoot you between the eyes.”

The reverberations from Order No. 3 never really ceased. It was the first official news of slavery’s end and just as importantly, specifying equality of rights.

Initially, Juneteenth was a holiday celebrated by former slaves and their descendants. It became an official Texas holiday in 1979.

#juneteenth#civilwargeneral#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarincolor#historyincolor#historyinfullcolor#gengordangranger#gengranger

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boys dressed up in school uniforms pose with king penguins at the London Zoo, 1953. Photograph by B. Anthony Stewart and David S. Boyer, National Geographic Creative

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

General of the Army, Douglas MacArthur

“I shall return” – U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur

On December 8, 1941, Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Far East Air Force in the Philippines was destroyed in a surprise attack by the Japanese.

The Japanese drove the retreating Allied Forces on to the Bataan Peninsula. MacArthur established his headquarters on the island fortress of Corregidor.

In March 1942, MacArthur and his family were ordered to leave the area and escape by PT boat to Australia by President Franklin Roosevelt.

MacArthur and FDR had first met prior to World War I. As Governor of New York, FDR told an adviser that he thought MacArthur was one of the two “most dangerous men in America.”

As President, FDR told MacArthur, “Douglas, I think you are our best general, but I believe you would be our worst politician.”

MacArthur would spend the next two years and a half year commanding an island-hopping operation in the Pacific.

On October 20, 1944, MacArthur would wade ashore at Leyte Island as the battle still raged. As the World watched, MacArthur announced, “I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil.”

On December 18, 1944 General Douglas MacArthur would receive his fifth star.

On September 2, 1945, MacArthur accepted the Japanese surrender aboard the USS Missouri.

0 notes

Photo

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, circa 1944

"… he is the most even-tempered person in the United States Navy. He is always in a rage." – Adm. Ernest J. King’s daughter

On December 17, 1944 Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King would receive his fifth star.

King is the only person to serve as both the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) at the same time.

King’s fifty-five years of service included experience on surface ships, submarines and, as commander of an aircraft carrier, learning to fly planes. Some considered King an organizational genius.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, King had to spread his ships over two separate Wars even though most of the major ships were out of commissioned for a year. King asserted, “We must do all that we can with what we have.”

On November 23, 1942, King wrote President Franklin D. Roosevelt pointing out that he had reached the mandatory retirement age of 64 years. Although he would describe King as a man “who shaves with a blow torch,” FDR respected his abilities. FDR replied, “so what old top?” King carried on.

#ernstking#admking#5staradm#cno#cominch#ww2adm#worldwar2 photo#ww2colorphoto#worldwar2#wwii#historyincolor#historyinfullcolor

0 notes

Photo

General of the Army George Marshall

“I couldn’t sleep nights, George, if you were out of Washington.” – U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

On December 16, 1944, Gen. George Marshall would receive his fifth star. Although he is one of the most decorated and respected military leaders in American history, he never commanded troops in battle.

As Chief of Staff from 1939, he oversaw the expansion of the military. Marshall knew that success in World War II required harmonious civil-military, interservice, and interallied relationships.

Winston Churchill described Marshall as “the true ‘organizer of victory.’” As such, Marshall’s opportunity to assume command during the cross-Channel assault was denied by FDR’s need for him in Washington.

After the War, Marshall was appalled by the destruction and despair he saw in Europe. He knew something needed to be done. During the 1947 graduation ceremonies at Harvard, Marshall announced the need for a “European recovery program.” The program would become known as the “Marshall Plan.”

#gengeorgemarshall#genmarshall#marshallplan#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#ww2colorphoto#ww2general

0 notes

Photo

Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy

“Bill, if we have a war, you’re going to be right back here helping me run it.” – U.S. Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt

On December 15, 1944, Adm. William D. Leahy would become the first officer in World War II to receive his fifth Star. Leahy had come out of retirement on July 6, 1942, to serve as the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Photographs of WWII would record him hoovering a few feet behind Roosevelt, not as one of the most powerful men of the time.

Friends before the War, Roosevelt was able to relax with Leahy and discuss decisions big and small. In his role as the “Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief”, Leahy would meet with Roosevelt each morning to determine the strategic decisions of World War II.

In 1943, Leahy was with Roosevelt at the meeting of the “Big Three”, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin in Tehran. As a ploy on D-Day, Leahy was featured in a photo op in an Iowa corn field and would give a commencement speech at a small college:

“Everybody may have peace if they are willing to pay any price for it,” Leahy said. “Part of this any price is slavery, dishonor of your women, destruction of your homes, denial of your God. I have seen all of these abominations in other parts of the world paid as the price of not resisting invasion, and I have no thought that the inhabitants of this state of my birth have any desire for peace at that price…”

Only Leahy knew that within 24 hours, Americans would be fighting and dying on French soil.

#admleahy#williamleahy#franklinroosevelt#5staradm#worldwar2#ww2colorphoto#wwllphoto#ww2adm#historyincolor#historyinfullcolor

0 notes

Photo

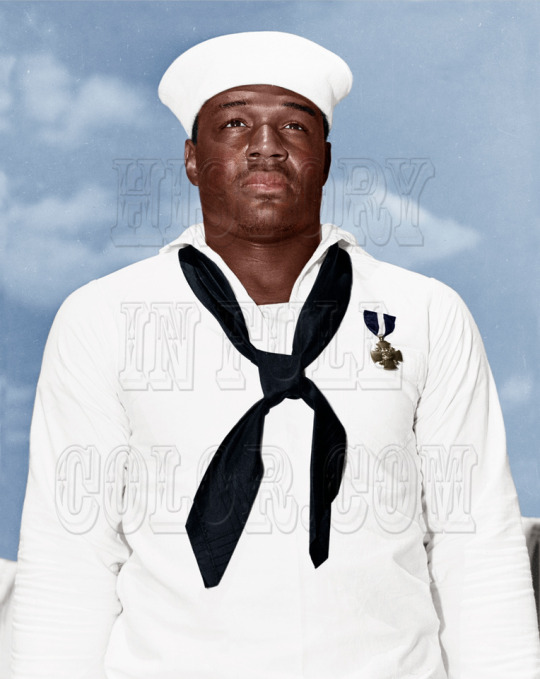

Doris “Dorie” Miller, 1st African-American to receive Navy Cross

“… when the Japanese bombers attacked my ship at Pearl Harbor I forgot all about the fact that I and other Negroes can be only messmen in the Navy and are not taught how to man an antiaircraft gun.” - Doris “Dorie” Miller, 1st African-American to receive Navy Cross

On December 7, 1942, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. On board the USS West Virginia, moored at battleship row, was Mess Attendant 2nd Class Doris Miller. Miller was below decks working on the laundry when the first torpedo struck.

On the signals deck, the ship’s commanding officer, Capt. Mervyn Sharp Bennion, lay mortally wounded, refusing to leave the deck. Miller, the ship’s heavy weight boxing champion was tasked with moving Bennion to a sheltered spot aft of the conning tower.

The ship was listing. It had been hit by two bombs and six torpedoes. The port guns went silent, but the starboard guns still were operational. Miller was ordered to feed ammo into a pair of .50-caliber Browning machine guns. As Lt. J.G. Frederic H. White fired one gun at the Japanese, Miller took control of the other gun.

“It wasn’t hard. “I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine,” recalled Miller.

White later reported that Miller “didn’t know very much about the machine gun, but I told him what to do and he went ahead and did it. He had a good eye.”

Lt. Cmdr. Johnson recalled Miller “blazing away as though he had fired one all his life.”

Out of ammunition Miller made his way down to the boat deck, helping pull sailors from the burning water, saving lives. The order was given to abandon ship. Miller would be one of the last three men to leave the West Virginia.

Later, Miller told his brother that, “with those bullets spattering all around me, it was by the grace of God that I never got a scratch.”

The after-action reports of the heroism “equal to any in the U.S. naval history” included the actions of a unknown black sailor. How to honor the heroic actions of the unnamed African-American was debated.

Miller, as a symbol, became a catalyst for desegregation and equal opportunity. An all-black section of the U.S. Naval Training Station at Great Lakes, Ill. was created to provide equal opportunities for black recruits. On May 27, Adm, Chester W. Nimitz presented Miller with the Navy Cross. As part of a public campaign, Miller was assigned to promote war bond sales for two months. The son of a Texas sharecropper, Miller would address the first class of black sailors to graduate Camp Robert Smalls.

As opportunities for African Americans grew in the military. Miller was reassigned to the USS Liscome Bay as a mess attendant and was promoted to cook, third class. His new ship was a CVE, assigned to support the Invasion of Makin.

On November 24, 1943, the Liscome’s lookout shouted, “Christ, here comes a torpedo!” The ship’s bombs, bunker oil, aviation fuel and cannon shells exploded. The ship sank within 23 minutes. Miller was listed as “presumed dead”. His body never recovered.

#pearlharbor#worldwar2#ww2#ww2colorphoto#usswestvirginia#ussliscomebay#dorismiller#doriemiller#navycross#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor

1 note

·

View note

Photo

General Rufus Ingalls coach dog; City Point, Virginia, March 1865

“I am General Ingalls’s dog; whose pup are you?”

In City Point, Va., U.S. Gen. Rufus Ingalls’s popular dog became the focus of photographers. U.S. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s and cavalry officer’s horses would pose for pictures. Fighting units would include their mascots when they were photographed. The dog would become one of the few pets to be photographed at least five times during the Civil War.

In the 1860’s Dalmatians were a rare breed in America. Furthermore, dogs were uncommon in an army camp. Ingalls had returned from a trip to Washington D.C. with the Dalmatian. The men enjoyed seeing the popular officer accompanied by his friend in fur.

When Grant ran into his former West Point classmate Ingalls, he too would remark on the dog.

In Horace Porter’s book, “Campaigning with Grant”, we have a report of Grant-Ingalls interaction that includes the dog.

“One evening, as the general was sitting in front of his quarters, Ingalls came up to have a chat with him, and was followed by the dog, which sat down in the usual place at its master’s feet.

“The animal squatted upon its hind quarters, licked its chops, pricked up its ears, and looked first at one officer and then at the other, as if to say: ‘I am General Ingalls’s dog; whose pup are you?’

“In the course of his remarks General Grant took a look at the animal, and said: ‘Well, Ingalls, what are your real intentions in regard to that dog? Do you expect to take it into Richmond with you?’

“Ingalls, who was noted for his dry humor, replied with mock seriousness and an air of extreme patience: ‘I hope to; it is said to come from a long-lived breed.’

“This retort, coupled with the comical attitude of the dog at the time, turned the laugh upon the general, who joined heartily in the merriment, and seemed to enjoy the joke as much as any of the party.”

#civilwargeneral#genrufusingalls#geningallsdog#geningall#citypoint#gengrant#genulyssesgrant#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Chief Joseph

“Our fathers were born here. Here they lived, here they died, here are their graves. We will never leave them.” – Chief Joseph

In the 1870s, the Nez Perce Indians were living on their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley, Oregon. As American settlers moved into the area, the Nez Perce were repeatedly asked to move to the Idaho Territory. After several violent clashes, in 1877, the Nez Perce fled towards Canada for political asylum.

U.S. newspapers covered what would be referred to as the Nez Perce War. During a 1,170-mile fighting retreat, it was U.S. Gen. Oliver O. Howard vs. the Nez Perce warriors, women and children. The skill and courage of the Nez Perce earned the U.S. public’s admiration. Still, the U.S. Government pursued the fleeing people.

On October 5, just 40 miles from the Canadian border, the Army closed in on the Indians. They didn’t realize that the Army was tracking their movements by telegraph. Popular history has it that Joseph had said at the formal surrender:

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, to see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Instead of being returned home as per the surrender, the Nez Perce were shuttled from reservation to reservation. As a spokesman for his people, Chief Joseph would travel to Washington D.C. and New York City. He rode in a parade honoring former president Ulysses Grant with Buffalo Bill Cody. He met with President Theodore Roosevelt. Joseph consistently requested that his people would be allowed to return to the Wallowa Valley. It never happened.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Firing a Quaker Gun, Centreville, VA 1862

"[I]t was a favorite trick to run it out into the center of the road and go through the motions of loading a gun and pointing it at the enemy, who promptly stampeded, under the impression that we had a piece of artillery with us" - PVT Edgar Warfield, 17th Va., Munson's Hill, Va.

"Quaker Guns" - logs, usually painted black, have been used to deceive the enemy in North America since the American Revolution. Adding wheels to the log, made it virtually impossible to discern it was a fake from a distance. During the Civil War, both sides, including civilians would hoodwink their foe using logs, stove-pipes, kegs and more.

After the First Battle of Manassas, Va. on July 21, 1861, Col. J.E.B. Stuart's troops ended up approximately six miles from Washington D.C. at Munson's Hill, Va.. While Gen. Joseph Johnston reorganized the Confederate Army of the Potomac, Stuart dug earthworks that appeared to be up to 15' high and erected signal stations. Lacking actual cannons, he placed Quaker Guns in the trenches.

As Gen. James Longstreet later recalled, "the authorities allowed me but one battery. . . we collected a number of old wagon-wheels and mounted on them stove-pipes of different calibre, till we had formidable-looking batteries, some large enough of calibre to threaten Alexandria, and even the National Capitol and Executive Mansion."

For the next two months, Gen. George McClellan drilled the Army of the Potomac at the capital. Thaddeus Lowe would send up his observation balloons to check out the situation. Stuart was promoted to the rank of Brig. General. The Confederates kept busy firing at anyone approaching on the broad, flat plain called Bailey's Crossings below and the observation balloons above.

As there weren’t any major battles being fought, the newspapers focused on the Confederates above Washington, who alarmed everyone living at the capital by flying "an immense Confederate flag—the red, white, and blue stripes in which are at least five feet wide each—is the most prominent object upon the top of the eminence." According to the New York Times, it "was visible with a glass from the top of the shiphouse at the Navy-yard" in Washington D.C..

Longstreet recollected, "[w]e were provokingly near Washington, with orders not to attempt to advance even to Alexandria." Johnson on the other hand considered the Munson's Hill position as defensively unsound and logistically difficult to keep supplied. McClellan, by twice sending out heavy armed reconnaissance parties to probe the rebel lines, may have convinced Johnson that enough was enough. It was time for the troops to fall back.

On September 28, 1861, the Confederates abandoned Munson's Hill, leaving behind their Quaker Guns. After having been terrified by logs, the North proceed to mock the army in the newspapers and by song. McClellan was the target of "The Bold Engineer" and the situation was declared a "humbug - worse that a Bull-run" in the song, "The Battle of the Stoves-Pipes". However, as the war proceeded, the newspapers began to defend the generals by pointing out that without risking being fired upon, it is difficult to discern logs from actual cannons.

#quakergun#munsonhill#civilwargeneral#genjebstuart#genlongstreet#genjoejohnston#genjohnston#genMcClellan#thadduslowe#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Major General Lew Wallace; Savior of Cincinnati, Author of Ben Hur

“Think of the earth ten thousand men can move in one day! Then, if the Confederates give us a week, we can get half of Indiana and half of Ohio behind the breastworks." – U.S. Gen. Lew Wallace

On September 1, U.S. Gen. Horatio Wright, cmdr. of the Dept. of Ohio, requested U.S. Gen. Lew Wallace take command of the troops in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was feared that C.S. Gen. Kirby Smith having captured Richmond, Ky., would now target Cincinnati, the largest city west of Baltimore, Md. and north of New Orleans, La.

Wallace’s staff pointed out, “There is nothing at Cincinnati with which to make a defense – not a solider, not a gun, not a fort. To try must end in failure.”

Wallace, the future author of the 19th century’s bestselling novel Ben-Hur, came up with a plan.

On September 2, he enacted Martial law. Every able-bodied man would be given the choice “to work or fight.” He called in local surveyors and civil engineers to teach them military engineering, so they could construct the riffle pits and breastworks.

On the second day 15,000 men were sent across the river to begin the defenses.

Realizing the ferryboats could not move fast enough, Wallace called in the top local builders requesting construction of a pontoon bridge. They responded that it could be done within 48 hours. “… we will go up into the Licking River and fetch down coal-barges, which, with the help of a steamboat, we will tie and anchor and make into a bridge for you twenty-five feet in width from shore to shore”.

The railroads were running day and night. The foundry at Cincinnati contributed ten Napoleon guns. The arsenal in Indianapolis, Ind. sent all the ordnance they had. Both Ohio and Indiana sent men armed with their best weapons, some of which were Revolutionary War horse pistols.

By the fifth day of the proclamation, 72,000 were prepared to defend the area, 60,000 of them were irregulars a.k.a. the “Squirrel Hunters”. The men were fed by women making sandwiches around the clock.

“If the enemy should not come after all of this fuss,” said a doubting Wallace friend, “you will be ruined.”

On the 10th, C.S. Gen. Henry Heth and his column arrived at Covington. Heth’s intel had Cincinnati defended by logs painted black, hastily dug breastworks and impressed lawyers, doctors, shopkeepers as combatants; “… and that at the first shot they would break for the river.”

Instead of ordering an assault, the rebels looked over the fort, the recently constructed breastworks and the masses of people behind them.

On the morning of the 12th, the Confederates were gone.

#genlewwallace#genhenryheth#genheth#defenseofcincinnati#defenderofcincinnati#saviorofcincinnati#genkirbysmith#genhoratiowright#benhur#civilwargeneral#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarphoto#civilwarcolorphoto

0 notes

Photo

NYC Ticker Tape Parade for the Apollo 11 Astronauts - August 13, 1969

“[It] was an immense sonic boom of emotion. Confetti flew, people screamed and waved, and we waved back.” – Astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin

On August 13, 1969, NASA sent the Apollo 11 astronauts and their families on a whirl wind trip from Houston, to New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles all in one day.

New York City would welcome the Astronauts in a showering of ticker tape down Broadway and Park Avenue in a parade termed as the largest in the city's history. Fireboats sprayed a water salute. Boy Scouts carried American Flags. The parade launched from a pier near Wall Street to City Hall lasted about an hour and a half.

The Astronauts were in the lead car, pictured from the right, are Neil A. Armstrong, commander; Michael Collins, command module pilot; and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot. They were followed by a security car, the wives’ car, security car, their children’s car and another security car.

Mayor John Lindsay and his wife gifted the Astronauts keys to the City. In return, the men presented a photographed taken on the Moon. In another ceremony at the United Nations, the Astronauts were gifted with commemorative stamps from member countries.

The three families were whisked off to Chicago. Chicago threw a parade that “was even more overwhelming than the experience on Wall Street several hours earlier.” The Astronauts “were covered with confetti and streamers and perspiring so much that they were glued to us.” Mayor Richard Daley gifted the trio with silver punch bowls.

Next came a three-and-a-half-hour flight to Los Angeles. During his exploration of the plane Andy Aldrin discovered “an intriguing and mechanical-looking console up near the cockpit”. Informed that it was a telephone, he was asked if he would like to phone a friend. To the interest off all, Andy called a friend to announce, “… Nothing much, I’m on an airplane.” The other children lined up to make similar calls to their friends.

Arriving in Los Angeles, Mayor Sam Yorty presented the keys to the City. At the Century Plaza Hotel, President Nixon, his wife and daughters invited the Astronauts to their suite and gifted each of them with a statue. At the State banquet that evening, the Astronauts were presented with the Medal of Freedom.

Three days earlier, on Sunday, August 10, 1969, the Apollo 11’s crew were released from medical quarantine. Instead of rest and relaxation with their families, NASA sent them on the whirl wind trip. The Astronauts were grateful their children were included.

“The Aldrin children have always been late sleepers and grumpy risers. They weren’t enthusiastic about the trip because anything that began at 5:00 A.M. couldn’t possibly be worth it. We convinced them it was.”

#apollo11#neilarmstrong#michaelcollins#buzzaldrin#edwinaldrin#samyorty#johnlindsay#richarddaly#tickertapeparade#Presnixon#historyincolor#historyinfullcolor#medaloffreedom

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

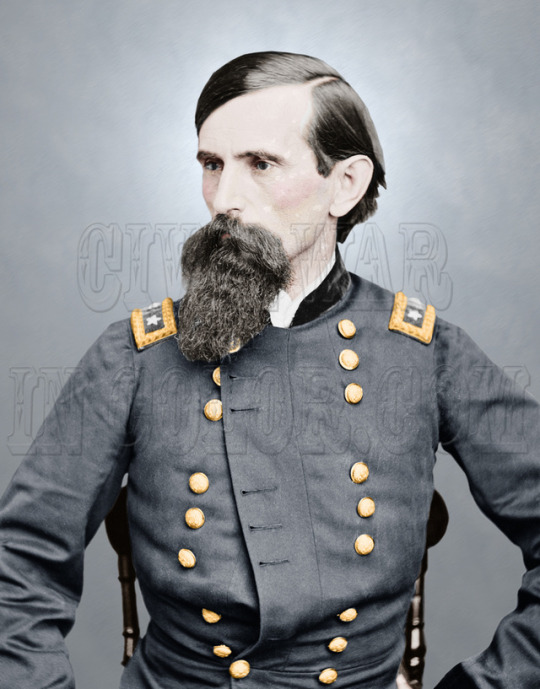

Adm. David Farragut & Gen. Gordon Granger

“Hold the Fort. …. Stop communicating with the enemy; all terms or stipulations made by you are annulled.” - C.S. Brig. Gen. Richard Page

By August of 1864, the Federal blockade had managed to shutter all but two major Confederate ports, Wilmington, N.C. and Mobile Bay, Ala.

To close Mobile Bay, U.S. Adm. David Farragut and U.S. Gen Gordon Granger headed a joint land sea campaign. The Army was tasked with capturing the twin masonry fortifications positioned at the mouth of the Bay, Ft. Morgan on a spit of land known as Mobile Point, designed to guard the shipping channel and Ft. Gaines on Dauphin Island, offering sheltered anchorage.

Today, West Point graduate U.S. Gen. Gordon Granger is best known for coming to the aid of U.S. Gen. George “Rock of Chickamauga” Thomas during the Battle of Chickamauga, Ga. and freeing the slaves of Texas on June 19, 1865, resulting in the holiday known as “Juneteenth”. Granger was candid and “for the mere tinsel of rank he had no respect”. He was a stickler for following military procedure but earned the ire of U.S. Gen. Ulysses Grant by refusing to move without basic supplies for his men. Granger used political pull to return to the field.

On August 3, Granger and 1,500 men landed on Dauphin Island, seven miles from Gaines, intent on making the Fort a staging area for taking Mobile. On the 4th, they were within 1,200 yards.

On the 5th, Farragut’s 199-gun fleet attacked. As agreed, Granger’s troops began shelling the Fort with six 3-in Rodman guns. His sharpshooters climbed the surrounding sand dunes, shooting down into Gaines. From the north, came shells from monitors USS Chickasaw and USS Winnebago.

C.S. Col. Charles Anderson led the 21st Ala., reservists and cadets from Pelham Military Academy, Ala. that made up the 800-man garrison of Ft. Gaines. The Federal government had almost finished remodeling Gaines before the War began. Armed with 26 guns, including four 10-inch columbiad guns, the 22-foot high walls were designed to survive a six-month siege, had a rain catchment system and the latrines were flushed by the tide. It would come as a shock to her defenders that rifled guns had made brick walls obsolete.

On the 6th, the officers petitioned Anderson to surrender. Although inclined to hold out, Anderson realized, “We could render Mobile no assistance. We could render Morgan no assistance, and we could have done no harm to the enemy.” Furthermore, he could have a mutiny on his hands. He sent word to Farragut for honorable surrender terms.

At 8:00 a.m. on the 8th, Anderson formally surrendered Gaines, the POWs were sent to New Orleans, La. and the Stars and Stripes flew above.

“I found the fort in excellent order,” reported Cpt. Miles McAlester, Chief Engineer. He noted that its defenses, “… was utterly weak and inefficient against our attack (land and naval), which would have taken all its fronts in front, enfilade, and reverse.”

Commanding Ft. Morgan and all Mobile Bay’s defenses was C.S. Brig. Gen. Richard Page, cousin of C.S. Gen. Robert E. Lee and former Farragut friend. Page spotting the truce boat was livid. He repeatedly sent messages to Anderson to not surrender via boat and telegraph.

C.S.A. President Jefferson Davis vowed to put Anderson on trial if exchanged. Page called the surrender, “… a deed of dishonor and disgrace to its commander and garrison.”

#davidfarragut#admfarragut#admiralfarragut#gengranger#gengordongranger#battlemobilebay#battleofmobilebay#ftgaines#ftmorgan#dauphinisland#usschickasaw#usswinnebago#colcharlesanderson#milesmcalester#genrichardpage#genpage#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto#pelhammilitaryacademy

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

U.S. President Nixon Welcomes the Apollo 11 Astronauts on USS Hornet

“… this is the greatest week in the history of the world since the Creation, because as a result … the world is bigger, infinitely, and also … the world has never been closer together before.” – U.S. President Richard Nixon

On July 24, 1969, Apollo 11 returned to Earth. On arrival to the recovery ship, the USS Hornet, the crew were welcomed back to Earth by U.S. President Richard M. Nixon.

The Astronauts spent years practicing and preparing for every contingency from lift off to splashdown.

The men knew once they reached the recovery ship, the USS Hornet, they were going to spend the next 21 days confined to the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), for medical isolation. It was a precaution against an uncertain threat of contagion.

After eight days of travel, the men showered, changed and opened the curtains on the MQF. Outside the curtains, the world’s media awaited.

#apollo11 presnixon#usshornet#neilarmstrong#michaelcollins#buzzaldrin#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

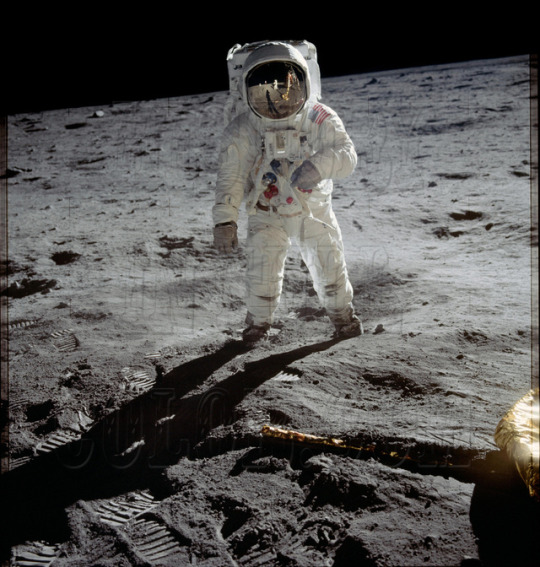

Apollo 11 Astronaut Edwin “Buzz” E. Aldrin Jr Buzz Aldrin on Moon, Armstrong's reflection in Visor

“I don’t believe that any pair of people have been more removed, physically, from the rest of the world than we were. – Astronaut “Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin

In Aldrin’s visor, a reflection of Neil Armstrong can be seen snapping this picture. Earlier on July 20, 1969, the pair had become the first men to land on the moon in the Lunar Module (LM) known as “Eagle”. As anticipation around the world grew, it took hours before the first man was ready to walk on the Moon.

Instead of two, it took three hours for the men to prepare for the Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA). Struggling to change into their protective spacesuits in the LM’s cramped quarters “… felt like two fullbacks trying to change positions inside a Club Scout pup tent”, recalled Aldrin.

The hatch door finally opened. In his bulky spacesuit Armstrong needed guidance to crawl backwards out of the LM onto the Eagle’s “porch”. Armstrong had to be reminded to pull out the cabinet (MESA) containing the television camera to beam the first step on the moon to Earth.

As world watched, Armstrong slowly made his way down the ladder, aware the last small step was 3.5 feet above Lunar surface. Walter Cronkite inquiring on why it was taking so long was told that Armstrong, “doesn’t have eyes in his rear end.”

At last, Armstrong stated, “I’m going to step off the LM now.”

Across the Earth, millions of people watched as Armstrong became the first man to step on the Moon.

“That’s one small step for (a) man. One giant leap for mankind.” – Neil Armstrong

1 note

·

View note

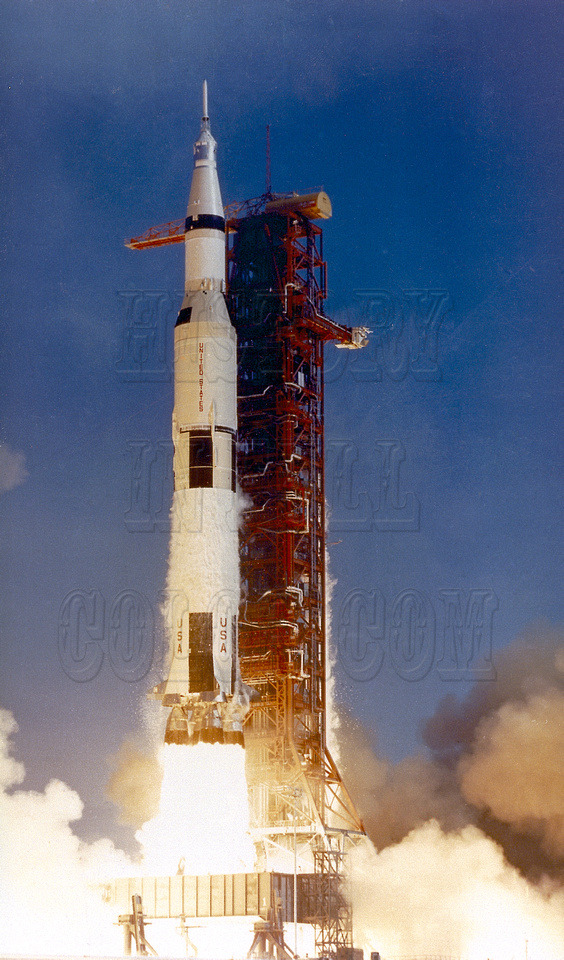

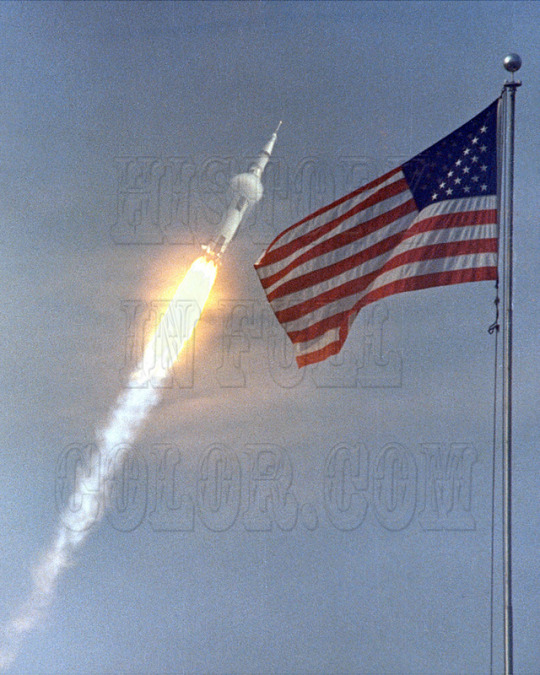

Photo

Apollo 11 Liftoff with Tower, Saturn rocket fire

“Shake, rattle, and roll! Noise, yes, lots of it, but mostly motion, as we are thrown left and right against our straps in spasmodic little jerks.” – Michael Collins, Apollo 11, Module Pilot

Apollo 11 lifted off at 9:32 a.m. (EDT) on July 16, 1969. For the Spectators, located 3.5 miles away, the rocket rose in silence. The roar reached them 15 seconds later accompanied by “tremors under the feet and pounds to the chest.”

Television viewers across the world saw Walter Cronkite pelted by ceiling tiles and insulation falling from within the broadcast trailer. The roof of the Petrone’s Launch Control Center rolled “like an earthquake”.

Slowly the rocket rose. The Spectators screamed, “Go! Go! Go! Go!”

“There was this enormous light, and the rocket goes up and up, and then it goes through the first skiff of clouds, and then through the second skiff of clouds, and then you see a puff of smoke – the first burnout -- and then the rocket disappears,” selenologist Harold C. Urey remembered.

Inside the rocket, Neil Armstrong had a different reaction. “The reality is, a lot of times you get up and get in the cockpit, and something goes wrong somewhere and you go back down. So, actually, when you actually lift off, it’s a really a big surprise.”

#apollo11#saturnv#spacemission#moonlanding#apollolaunchpad#apollolaunch#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#neilarmstrong#michaelcollins#haroldurey

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Apollo 11, Saturn V Launch Vehicle Rollout

“One wonder to me was that no Saturn V Rocket ever blew up.” - Michael Collins, Apollo 11 Command Module pilot

In preparation for the Apollo 11 mission launch, the 363-foot-tall, 6,400 pound Saturn V Launch Vehicle is literally rolled out to the Launch Pad.

Super chilled LOX and LH2 fuels powered the Saturn V. The material was difficult to manufacture, store and transport. But had an extremely efficient ratio of propellant weight to firing power.

The fuel would cause all 30 stories of the missile to wheeze and groan like a living “monster”. The cryogenic tanks caused dew to freeze on the rocket’s skin; falling like snow during launch.

The Saturn V had 6 million parts. A week before launch, a leak was discovered. The leak was traced to a manifold. It would take four days to replace the manifold, canceling the launch date. A tech carefully tightened a nut, fixing the problem.

The Saturn V was good to go for the Apollo 11 mission launch on July 16, 1969.

#apollo11#saturnv#spacemission#manonmoon#moonlanding#apollolaunchpad#saturnvrollout#launchvehicle#launchrollout

0 notes