Text

Yes, but compare with his Greek:

(chpt. 5)

Love the way Henry always mechanically goes:

466 notes

·

View notes

Text

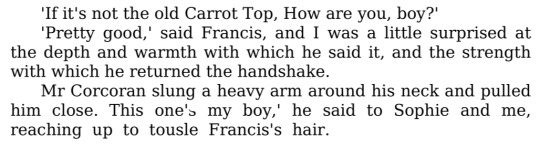

Francis the Carrot Top

In chpt. 7 Francis and Richard arrive to Shady Brook for funeral and meet Mr Corcoran:

This scene shows that, unlike his friends, Francis was quite fond of Mr Corcoran, and vice versa. But why exactly Carrot Top? Not that it was an uncommon tease, it still sounds peculiar.

There's a wordplay, of course: Bunny was gnawing on Carrot, so Carrot killed Bunny — prey becomes the hunter, if we can think of rabbits and vegetables in that fashion.

And another possible wordplay. There's an idiom 'carrot and stick', in which carrot means a reward, something that is used to tempt/seduce — Francis is a seducer.

That's it, unless "Carrot Top" stands for something more particular.

I think, it might imply a classic French story about miserable childhood "Poil de Carotte" (1894) by Jules Renard, translated as "Carrot Top" in English.

[pic source: pinterest]

This assumption is based on a specific set of features, which belong to the main character. In short, it goes like this:

A boy François, called Carrot Top because of his red hair, has an extremely problematic relationship with his mother, living under pressure and suffering humiliation from his milieu in the French country. He's sometimes ironic, sometimes a bit cruel, and chronically unloved. Life seems bitter, and young François desires love and recognition.

Name, appearance, experience and personality — all that sound too familiar in the context of TSH. Even an attempt of suicide in water is present here, though in a different way. And the author, Jules Renard, looks right in his place among other references to the Victorian era and Fin de siècle.

If a nickname "Carrot Top" in TSH actually relates to that French book, at least as to a source of inspiration, it might add a dramatic undertone to the background of Francis Abernathy.

In many respects Francis appears to be not that spoiled as it was depicted initially. His alcoholic mother was shown at once neglecting and controlling. And with such a childhood even Mr Corcoran would give the impression of exemplary father figure, evoking "depth and warmth".

Or it can be just another grain of sand on the shores of Metahemeralism.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

@massivetimemachinemagazine Excuse me, with all due respect, I am mostly indifferent to biographical criticism of that sort.

Ok, Todd O'Neal must've been a sweet guy if he so generously gave Henry his cigarettes, chip in his tooth, and eye problems. But it makes no difference, since the novel is about metaphysics. It's not roman-à-clef, it doesn't make sense. In my humble opinion, Tartt's conversion to Catholicism and particular elements of cultural background are more important than her classmates when it comes to understanding the novel.

Very interesting of Donna Tartt not to given Bunny a single redeeming quality. Even the Corcoran family is specifically designed so that you can offer them almost no sympathy. It would’ve been interesting if Bunny was a ball of sweet sunshine and was torn between a moral obligation to tell the truth about the dead farmer and is love for his friends especially Henry. Instead of just being like 100% terrible.

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Secret History & Greek letter Ψ

I’m sure, many readers noticed that Julian, despite his outspoken prejudice against psychology, described the seduction of Dionysiac ritual in terms of psychoanalysis, like this:

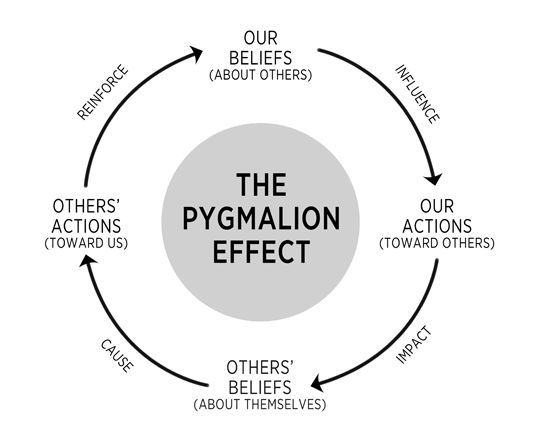

Even more funny is that Julian’s method of teaching is probably based on psychological theory from the late 60s. I mean, the Pygmalion effect.

Source of image: steemit.com

According to Richard, Julian:

Meanwhile, Julian’s students represent the psychic structure of personality:

Henry is the Superego, the all-controlling perfectionistic intellect;

Bunny is the Id, the suppressed unconscious;

Francis is Libido, the sexual energy;

the twins are Anima and Animus, the masculine and feminine sides of human Self.

Richard must be the Ego, a poor neutral, influenced by everyone else.

Julian Morrow in this scheme plays the role of religious thinking in the human mind (the idea of god). In the novel it comes how it was interpreted by Søren Kierkegaard: religion serves as a mediator in Self’s relation to the Other. But also, the god here is an idea of absolute Other, which helps to shape human identity as opposed to something that is not human at all — consider how Henry identified Julian as a deity.

So, Julian and his students together construct an integral psychological model of personality. A personality in crisis, as one could assume.

[Psychology is relevant, because we have a foreshadowing for it: during the year Richard was working part-time for professor of psychology Dr Roland, assisting in his 'vague research'. And there was a dialogue with Richard (chpt. 1), when Julian said that ‘psychology is only another word for what the ancients called fate.’ He also told Richard that he always knew what his students were going to do, like an omniscient god.]

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tartt also probably used Eliot's essay on Dante for Henry's explanation of bacchanal to Richard in chpt. 4, but inverted the meaning.

According to Henry, Julian said that the Divine Comedy is 'incomprehensible to someone who isn't a Christian. That if one is to read Dante, and understand it, one must become a Christian if only for a few hours. It was the same with this. It had to be approached on its own terms, not in a voyeuristic light or even a scholarly one.'

Eliot actually argued for the opposite. He acknowledged that 'In reading Dante you must enter the world of thirteenth-century Catholicism'.

However,

'You are not called upon to believe what Dante believed, for your belief will not give you a groat’s worth more of understanding and appreciation'

and

'I will not deny that it may be in practice easier for a Catholic to grasp the meaning, in many places, than for the ordinary agnostic; but that is not because the Catholic believes, but because he has been instructed. It is a matter of knowledge and ignorance, not of belief or scepticism.'

Maybe, Tartt wrote that in act of polemic with Eliot. Or the inversion is her typical method of making allusions)

I was reading this article in The New Yorker about the 100th anniversary of the publication of T.S. Eliot’s poem, “The Waste Land,” and there’s so much Secret History in here. Of course, Donna Tartt quotes the poem directly in the “Elizabeth and Leicester” scene on the lake at Francis’s country house. But this article made me see Eliot’s influence in less conspicuous ways.

Eliot:

“Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood,” he wrote, in an essay on Dante. “It is better to be spurred to acquire scholarship because you enjoy the poetry, than to suppose that you enjoy the poetry because you have acquired the scholarship.”

The Secret History:

“In very great poetry, the music often comes through even when one doesn’t know the language. I loved Dante passionately before I knew a word of Italian.”

Eliot:

I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

The Secret History:

Gloomily, I thought of Monmouth House: empty corridors, old gas-jets, the key turning in the lock of my room.

Eliot:

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

They called me the hyacinth girl.”

The Secret History:

She was still a girl…a slight lovely girl whose hair smelled like hyacinth…

Especially significant when it comes to the death of one slow-witted college boy who couldn’t keep his mouth shut, the famous opening line from “The Waste Land”:

April is the cruellest month

And the poem’s very last words:

Shantih shantih shantih

Eliot says in his own “Notes on The Waste Land” that these are “a formal ending to an Upanishad.” Which of course reminds me of Henry’s choice of reading matter at Bunny’s funeral:

“I was reading,” he said.

“What is it? Something good?”

“The Upanishads.”

I’m sure there are hundreds of references and influences in The Secret History that I will never catch, but of one thing I’m certain: nothing in this book, not even the most random-seeming detail, is here by chance. That’s how you know you’re in the presence of genius.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

You're so right. If you allow me to say so, Henry actually was a very empathetic guy. It's just his empathy was not emotional, rather of an intellectual kind.

I presume that the most important thing for him was to keep his friends happy.

In the end, when Henry tried to explain why they killed Bunny to Julian, he told that Bunny 'wasn't a happy person in those last months.' In that moment Henry was astonished, shocked with situation, he didn't expect that Julian would discover the truth. So, I think, he spoke sincerely, absolutely honest. He really believed in this, and he thought that Julian must've understood his motivation.

I hope you remember that morning in the country when Henry asked Richard 'You're not very happy where you come from, are you?' I think it was important for Henry that Richard felt happy with them.

Later Camilla told that Henry decided not to repeat the purification with piglet because it could upset Richard. What if he really didn't want to upset him?

When Henry gave money to Bunny, paid for their trip to Italy, paid for his purchases, he tried to make Bunny happy all that time. But he couldn't, and it was a problem which he solved by killing his friend. It's a very perverted, paradoxical way of thinking, though it was not out of moral relativism.

And then were Camilla and Charles. Henry couldn't make happy both of them, so he chose only one. Charles was unhappy, so Henry tried to kill him with nembutal.

In Epilogue Francis said that when he was lying in his bloody bath, he saw a hallucination of Henry saying 'Well, Francis, I hope you're happy now.' And in Richard's dream he also talked about being happy.

I think that was his main purpose when Henry commited suicide: to make everyone happy, as they were unhappy because of him. He understood it, since Richard asked him before, in the rose garden: 'Why do you have to make things so hard for everybody?'

Honestly Henry did commit horrible and inexcusable and unforgivable acts but it doesn't mean that every single thing he ever did for the entire book had to be out of ill intent.

He didn't save Richard during Winter to get him to trust him, he saved him because Richard was his friend he found freezing to death in an attic. He wasn't manipulating Camilla, he loved her and was trying to protect her and prevent her abusive brother from hurting her any more. He killed himself for a lot of different reasons but one of them was that it really was the only remaining way he could find to get everyone out of trouble and make things somewhat right again.

He surely was detached, and while he generally didn't feel as strongly as other people and even suppressed his own emotions to try and always be as rational as possible, it's not like he was completely incapable of feeling anything at all. In his own aloof way, he did care for them. I think that it's really the fact that despite everything there was some good in all of them that makes them so compelling, Henry included.

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be serious, there's nothing too specific. Tartt portrayed Francis as a dandy, and it's just a coincidence that I had erratic interest in dandyism some time ago — for fun, it was nothing special, tbh.

And I've got curious about things in TSH that I couldn't understand, so I did some research.

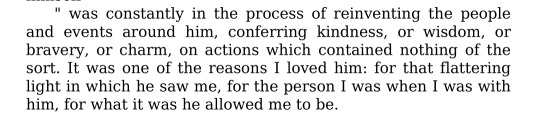

There's an article in which Tartt was named 'a privately idiosyncratic T. S. Eliot freak' (J. Kaplan, 'Smart Tartt'). I wanted to know why, and how this Eliot's frame could help to interpret the novel. I found a lot of things in TSH that somehow recall Eliot's biography, studies, works, poems. A plenty of things, if you know what to look at.

It's hard to decide what information is relevant for TSH and what is not, but if Tartt wrote the novel for about 8-9 years, she did a lot of reading, I guess.

The 'Eliot frame' sometimes helps: if Eliot wrote about something, Tartt as his 'freak' definitely knew about it. Eliot liked Sherlock Holmes stories, and he wrote criticism on Baudelaire. Mark Twain is here because he is from Missouri, like Eliot and Henry Winter, and Eliot wrote an introduction to Huckleberry Finn.

These 'connections' must be something called intertextual analysis, or whatever. But I am just a little cat, and my little paws can't do serious studies.

Btw, there was a fine study by F. Pauw — "If on a winter's night a reveller": the classical intertext in Donna Tartt's The Secret History.

He gave a short account of references to Eliot in the novel:

But there's much more, and I haven't found anything about Eliot's intertext in TSH on web. So I make some trivial observations, keeping in mind that TSH needs a commentary, like Joyce's Ulysses.

I should say, there's an amazing cycle of lectures on YouTube 'The works of T. S. Eliot' by Victor Strandberg. It made me reconsider the way of reading TSH.

(Idk what's the problem with comments, it's not me it's tumblr.)

Francis Abernathy: fake pince-nez

I was wondering where Francis ‘borrowed’ this accessory, so let there be some observations.

First of all, there’s a sassy definition of a typical dandy by Paul de Saint-Victor (La Presse, 21 August 1859):

'Black Prince of Elegance, the demigod of boredom who looked at the world with an eye as glassy as his pince-nez, suffering because his disarranged cravat had a crease, like ancient Sybarite who suffered because his rose was crushed.'

Then I thought that red hair combined with pince-nez reminds of Ezra Pound, known for his dandyish style and some other unpleasant things.

[Considering that Henry Winter could be read as a projection of T. S. Eliot, I think it's logical to compare Francis to Eliot's friend Pound, who edited The Waste Land, btw.]

Pince-nez also wore Mark Twain, another elegant redhead. Speaking of Twain, he left a description of one notable encounter in his Autobiography (vol. 2, 1924):

'Last night I was at a large dinner party at Norman Hapgood's palace uptown, and a very long and very slender gentleman was introduced to me — a gentleman with a fine, alert, and intellectual face, with a becoming gold pince-nez on his nose and clothed in an evening costume which was perfect from the broad spread of immaculate bosom to the rosetted slippers on his feet. His gait, his bows, and his intonations were those of an English gentleman, and I took him for an earl.'

Dapper-looking, tall, thin young gentleman in pince-nez, giving an impression of English aristocracy at uptown dinner parties. Doesn’t it sound like Francis?

Another possible source is 'The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez', one of Sherlock Holmes short stories. This pince-nez belongs to a refined and well-dressed lady, who committed an accidental murder, and then committed a suicide.

Eventually, when I was reading a review on Baudelaire’s last oeuvre, among his notes about Belgium I discovered a curious fact: Baudelaire complained that Belgians sold pince-nez with plain glass as a fashion accessory.

So I put my nose into that piece of prejudiced decadent writing:

'The pince-nez, with its cord, perched on the nose. A multitude of vitreous eyes, even among the officers. An optician told me that the majority of pince-nez that sells are clear glass. Thus this national pince-nez craze is nothing more than a pathetic effort to appear elegant and yet one more sign of the spirit of imitation and conformity.'

Late Fragments: Flares, My Heart Laid Bare, Prose Poems, Belgium Disrobed, trans. by Richard Sieburth (p. 301)

Francis bought his phony pince-nez in Belgium. That's it.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francis Abernathy: fake pince-nez

I was wondering where Francis ‘borrowed’ this accessory, so let there be some observations.

First of all, there’s a sassy definition of a typical dandy by Paul de Saint-Victor (La Presse, 21 August 1859):

'Black Prince of Elegance, the demigod of boredom who looked at the world with an eye as glassy as his pince-nez, suffering because his disarranged cravat had a crease, like ancient Sybarite who suffered because his rose was crushed.'

Then I thought that red hair combined with pince-nez reminds of Ezra Pound, known for his dandyish style and some other unpleasant things.

[Considering that Henry Winter could be read as a projection of T. S. Eliot, I think it's logical to compare Francis to Eliot's friend Pound, who edited The Waste Land, btw.]

Pince-nez also wore Mark Twain, another elegant redhead. Speaking of Twain, he left a description of one notable encounter in his Autobiography (vol. 2, 1924):

'Last night I was at a large dinner party at Norman Hapgood's palace uptown, and a very long and very slender gentleman was introduced to me — a gentleman with a fine, alert, and intellectual face, with a becoming gold pince-nez on his nose and clothed in an evening costume which was perfect from the broad spread of immaculate bosom to the rosetted slippers on his feet. His gait, his bows, and his intonations were those of an English gentleman, and I took him for an earl.'

Dapper-looking, tall, thin young gentleman in pince-nez, giving an impression of English aristocracy at uptown dinner parties. Doesn’t it sound like Francis?

Another possible source is 'The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez', one of Sherlock Holmes short stories. This pince-nez belongs to a refined and well-dressed lady, who committed an accidental murder, and then committed a suicide.

Eventually, when I was reading a review on Baudelaire’s last oeuvre, among his notes about Belgium I discovered a curious fact: Baudelaire complained that Belgians sold pince-nez with plain glass as a fashion accessory.

So I put my nose into that piece of prejudiced decadent writing:

'The pince-nez, with its cord, perched on the nose. A multitude of vitreous eyes, even among the officers. An optician told me that the majority of pince-nez that sells are clear glass. Thus this national pince-nez craze is nothing more than a pathetic effort to appear elegant and yet one more sign of the spirit of imitation and conformity.'

Late Fragments: Flares, My Heart Laid Bare, Prose Poems, Belgium Disrobed, trans. by Richard Sieburth (p. 301)

Francis bought his phony pince-nez in Belgium. That's it.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

T. S. Eliot & The Secret History. Part II.

In the juvescence of the year

Came Christ the tiger

In depraved May, dogwood and chestnut, flowering judas,

To be eaten, to be divided, to be drunk

Among whispers

I found it quite curious to read these lines from 'Gerontion' in relation to Henry's suicide.

We see here the same inverted Christian imagery as in TSH, although in the novel it is entwined and overlaid with the Greek mythology.

It's possible that Tartt reconceptualized some of Eliot's ideas.

'Christ the tiger'

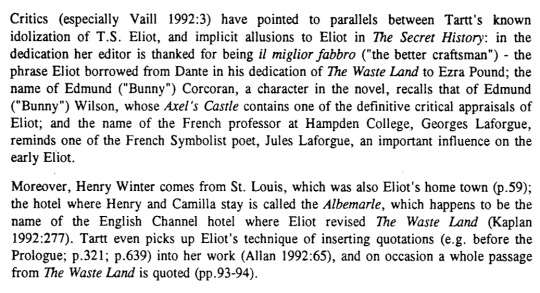

The following note to this line in Eliot's poem explains the origin of such a strange image:

the notes and the full text of 'Gerontion' here

In Bible wild-cats, lion and leopard, are the agents of divine wrath, sent to punish people for their transgressions, to slay and to watch (Jeremiah 5:6). Leopard is a measure of extreme swiftness (Habakkuk 1:8). And there's four-headed leopard (Daniel 7:6) which sometimes is interpreted as a symbol of Ancient Greece.

Wild-cats also scared Dante in the beginning of Divine Comedy, forcing him to step on the pass to hell.

'Christ is no wild-cat'. Yet, in TSH we deal with Dionysus who is strongly associated with wild-cats.

Jesus and Dionysus are juxtaposed in comparative mythology as gods with similar inventory: god disguised as a man, born by a human woman, usage of wine, rebirth/resurrection, ritual purification, etc. In a sense, Dionysus can be called the wild-cat Christ, or 'Christ the tiger'.

It reminds me of Henry's 'tigerish grace and swiftness', that surprised Richard (chpt. 8). And there was another comparison to a feline: 'Henry, generally, was clean as a cat' (chpt. 4).

On the other hand, in Christian tradition Jesus is usually depicted as a lamb. In TSH we see lambs only served up on a plate. It happens three times: the first dinner with twins; Richard's lunch with Julian; and Henry's last dinner at Albemarle hotel. Each of these meals preceded a death.

'In the juvescence of the year'

'In depraved May'

Back to the previous note. Lancelot Andrews suggested to celebrate Christmas in season of Easter as a more convenient time in terms of weather, because actual time isn't important for a mystery. Henry did the same when decided to set the bacchanal earlier in the autumn. [Dionysian mysteries were held two times a year: winter for the country festival and spring for great celebrations in the city.]

In TSH time is quite a tricky thing: there's no difference what time of year actually is, because Henry is always Winter — the season of bacchanal and Christmas. [We can think of the bacchanal as Dionysus Christmas.]

Such frozen time is an essential feature of afterlife, particularly in underworld like Hades or hell. But we can also consider annihilation of time in rituals and sacred mysteries, when time is frozen in a cycle.

[Cycle is basically a circle, the main element of construction in Dante's hell. Hell can be interpreted as cycles of suffering (like human life in Buddhism). There are nine circles of hell to pass — cats have nine lives.]

The Classics group lived in a stilled routine, which Richard named 'cyclical, Byzantine existence' (chpt. 2) — in cyclical time.

Henry killed himself when this cycle was ruined for good: time became linear, unfrozen, real.

Henry killed himself in May, the month when he at last started to live without thinking. It was personal spring of his life: time of love and resurrection of senses. But when the spring comes, Winter must end.

Winter met spring, the cycle of Dionysian mysteries was completed.

dogwood and chestnut, flowering judas

Dogwood is an important symbol in the novel. Dogwood flowers appeared in Richard's sight right before Bunny's murder, on the way to ravine and near it. Dogwood apparently contributes to the motif of dogs that recurs across the story.

Besides, earlier Richard compared Bunny to an old dog as he was fond of walks (chpt. 2) and had a specific manner of shaking wet hair (chpt. 5); and to a gun dog in his humiliating behaviour towards others (chpt. 5).

This association with dog looks quite curious in view of cat-and-dog relationship between Henry and Bunny.

Bunny was killed in the first day of 'dogwood winter', a short period of cold weather in the spring (acc. to Collins dictionary).

[In dogwood winter a dog-like guy was killed by a cat-like guy Winter in the woods behind the Cat-aract mountain. It's a crazy novel.]

When snow suddenly started falling to cover everything, including their crime, a curious dialogue took place:

It's Easter and spring, time for resurrection of nature and spiritual resurrection. But if flowers, an important element of this renewal, are killed, no resurrection will happen. Flowers can be interpreted here as a spiritual symbol, virtues of human soul.

Chestnut was mentioned only once, as a part of idyllic landscape around the country house in October (chpt. 2), some time before the bacchanal. Greeks called chestnut Zeus acorn. [Zeus is father of Dionysus, who gave him birth after keeping encased in his thigh.]

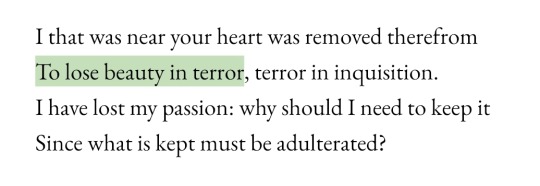

According to George Ferguson, in Christianity chestnut was a symbol of chastity, 'a triumph over the temptation of the flesh.' Etymology of this word is derived from Middle English 'chesten', and look at the meanings (b) and (c):

Source: Middle English Dictionary

Flowering judas-tree doesn't appear in TSH. But in the Classics group everyone is a traitor, one way or another. However, in Albemarle drunk Charles accused Richard of betrayal to his face. And earlier, in emergency room, Francis gave him 'a glare of hatred: et tu, Brute.'

The line 'To be eaten, to be divided, to be drunk' recalls how Julian described Dionysiac ritual: 'let God consume us, devour us, unstring our bones. Then spit us out reborn.' In Christianity god sacrifices himself, but in TSH god becomes a predator. Self-sacrifice of Christ the tiger doesn't bring redemption or salvation.

'Among whispers'. All that secretive whispers during the year, and whispers after Bunny's death. And the last whisper to Camilla.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

T. S. Eliot & The Secret History. Part I.

beauty and terror

These words occur together in the poem Gerontion, which Elliot originally included into The Waste Land:

Some critics suppose these lines to be extremely personal for T. S. Eliot. But is it even possible to lose beauty in terror?

I think, TSH can provide a response to this matter.

Tartt's paradox 'beauty is terror' relates to Freudian terms Eros and Thanatos, considering the context in which it was suggested:

The lecture proceeds with a question of what is desire, and Bunny answers 'to live forever'.

In Freud's drive theory Life and Death are two basic instincts that counterbalance each other in human existence as the opposite cosmological principles, the driving forces of civilization.

What happens in TSH can be seen as the result of ruined balance between these forces. Here both beauty and terror become the instances of the death drive, and nothing is left for Eros, the life.

Life without beauty is an empty desire.

So Henry Winter was infatuated with death: dead languages, dead knowledge, dead moon in the sky. With all his love to poetry, he knew that the most beautiful thoughts and feelings evolved from an encounter with the idea of death.

However, no word was said about beauty after the Battenkill murder. And when they planned to kill Bunny it was just 'redistribution of matter'.

Maybe 'to lose beauty in terror' actually means to lose the difference between these two concepts.

Henry's expression of triumph before he shot himself could've been the result of regained sense of beauty. Sublime beauty of tragedy, of course.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Winter, flirting

The first day of his visit to Francis’s country house Richard had a little voyage with Henry and Camilla in a boat. And here we have this introduction to Henry’s habits:

“He had a habit, as I was later to discover, of trailing off into absorbed, didactic, entirely self-contained monologues, about whatever he happened to be interested in at the time"

Richard was wrong, of course. Henry’s monologues were not ‘entirely self-contained’, they had particular purpose — at least, two of them were an instrument of mild pressure on Camilla, including this one which Richard heard during their voyage:

"That day he was talking about Elizabeth and Leicester, I remember: the murdered wife, the royal barge, the queen on a white horse talking to the troops at Tilbury Fort, and Leicester and the Earl of Essex holding the bridle rein… Camilla, flushed and sleepy, trailed her hand in the water… It was many years later, and far away, when I came across this passage in The Waste Land: Elizabeth and Leicester beating oars…”

T. S. Eliot left notes for these lines of his poem, citing History of England:

Author of this letter, Alvaro de la Quadra, was a Spanish diplomat and Catholic clergyman, he apparently had a right to marry a couple. For many years Leicester was queen’s favourite and suitor for her hand, but she didn’t want to marry — didn’t want to share her power with anyone, and used her claimed virginity as a political asset. Eventually, Leicester got tired of waiting, and married another woman, which broke the queen's heart.

In view of these facts, the boat scene in TSH looks so ironic. Richard’s surname, Papen, means ‘priest, cleric’ in North German, and he also was a foreign figure in their group, like that Spanish bishop in England. However, Richard wasn't able to marry anyone.

I guess, in such a manner Henry was telling Camilla: "I’m ready to be with you right here, now. But don’t make me wait for too long". And Camilla was flushed, because she understood this reassurance mingled with warning.

Another instance of this mild pressure was quoting passages about Emma Bovary, whose chaotic love choices ruined her life: Sa pensée, sans but d'abord, vagabondait au hasard, comme sa levrette, qui faisait des cercles dans la campagne… “Her thoughts were wandering at first without any purpose” — could it mean "Camilla, make up your mind, or you’ll end up like madame Bovary''?

From Henry’s point these monologues were probably a sort of flirting, an indirect way to show romantic interest towards Camilla.

Come on, Henry, why spend so many words, when you can say Cubitum eamus?

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pleasure is all mine, I'm glad you found my thoughts encouraging.

Actually, there’re a lot of little details in TSH that seem to be inspired by Vanity Fair:

Bunny’s nickname on campus — the Colonel, which also belongs to Rawdon Crawley. A piece of art that shows a man riding an elephant (TSH chpt. 6; VF chpt. 17). Maraschino liqueur, consumed in a moment of distress (TSH chpt. 6; VF chpt. 55). Even the name Camilla appears in regard to Rawdon’s sister as a reference to Aeneid (VF chpt. 10) — Tartt said that she picked it directly from Virgil, but who knows what influenced her choice.

And that amazing manner of depicting main female characters, when the language itself works as a disguise for their true intentions: a stream of sweet talk to create an alluring, glistening image, which is extremely hard to resist. If you liked Camilla, you must have an exquisite taste for good narration.

And that association with light — both Becky and Camilla are often shown illuminated in some specific way, or having bright, luminous details in their exterior. There’re a couple of instances when it looks like Tartt goes immediately after Thackeray. Like this one:

“Her complexion could bear any sunshine as yet” — the narrator flatters Becky after recounting how important is the quality of light for other ladies (VF chpt. 48).

“The light from the window was streaming directly into her face; in such strong light most people look somewhat washed out, but her clear, fine features were only illuminated” — Richard on Camilla (TSH chpt. 1).

What a rare compliment to admit that one's face can bear intense light, isn’t it?

The way Tartt ends her novel is very Thackerayan too, with no comforting closure or moral resolution. Just as Thackeray claimed: “I want to leave everybody dissatisfied and unhappy at the end of the story — we ought all to be with our own and all other stories.”

And it's so true that we can only speculate about some ambiguous moments. At times TSH makes me mad, because it feels like Tartt is just teasing with all that allusions and references. Although they can add something to her characters, the sum of possible perspectives appears to be self-contradictory. In the end I can only repeat that question of Richard: “How am I supposed to know what to think?”

I hope you'll enjoy your rereadings.

Macaulay twins & Thackeray

A nod to Vanity Fair in chpt. 2 makes not much sense at first, though for Richard it must’ve been rather alarming — Rawdon Crawley played cards to fleece his comrades.

However, this association may be a clue to understanding what is happening around the Macaulay twins in Book 2.

The parallel between Charles and Rawdon becomes more clear in retrospect, closer to end of the novel.

Both from respectable families but empty-headed, moneyless and dependent on relatives, they spend time drinking, gambling and screwing around. Both have debts — tend to be overly jealous — get arrested — get involved in love scandal with a rich rival — are ruined but ready to fight — end up in exile.

Yet, the only important thing here is Rawdon's relationship with his wife.

At her brother's elbow Camilla played the role of Becky Sharp in marriage with Rawdon: an attractive young couple that works in tandem, using their charm and wit to take advantage of wealthy friends, and exploiting affections of others to live a better life.

Francis gave some insights into this symbiotic relationship, describing it as 'they like to present a unified front but I don't even know how much they care about each other' (chpt. 8).

When Camilla abandoned this unified front, for Charles it was a betrayal as if she used to be his business partner, not just a lover or family member.

The most notable link to Becky is the role of Clytemnestra, performed by Camilla as well, and the symbolic meaning of it in both novels.

Like Clytemnestra, Becky Sharp is an archetype of a predatory female in disguise of false innocence. Strong-willed, cunning and bold, she’s a skilled actress and manipulator, still unable to predict the consequences of some of her actions.

At some point Camilla makes it clear to Richard that drunk Charles abused her, but Richard is surprisingly angry with her. He questions how Camilla got her injuries, because he feels that something's wrong (chpt. 8).

This situation looks quite peculiar in view of the analogy to Vanity Fair.

Camilla's counterpart, Becky Sharp, complained to her patron Lord Steyne that she experienced all sorts of injustice from Rawdon Crawley (VF chpt. 52). It sounds false, because Rawdon could’ve been a bully with other men, but with Becky he was a meek, submissive husband. All her complaints had only one purpose: to be pitied for her own benefit.

It's unclear to what extent this analogy works, but it may explain why Camilla wanted to put a distance between Richard and Charles. If she lied to Henry, or rather manipulated him, she wouldn't be glad to be exposed: just like in case with Bunny, Richard still was an alarm bell, the first person to whom the one can confide.

Thus she had to neutralise him. And thus she was unable to reconcile Charles and Henry later.

I dare say, Henry had seen what was going on, but he was glad to get rid of the third party in their love triangle anyway. Even Richard doubted his 'good' intentions.

Rawdon Crawley said about his wife: "if she's not guilty, ... she's as bad as guilty" (VF chpt. 55). It might illustrate Charles's point of view as well. Like Becky, his sister didn't want to bet on a losing dog. But even if Camilla had no evil intentions, the consequences of her actions were awful — she opened a Pandora's box.

According to Thackeray, “it is the unwritten part of books that would be most interesting”. And Donna Tartt used this principle full on, leaving all crucial events in shadows, but giving some hints to lead and mislead her reader through carefully constructed cultural references.

Which also can be just some Metahemeralism.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Macaulay twins & Thackeray

A nod to Vanity Fair in chpt. 2 makes not much sense at first, though for Richard it must’ve been rather alarming — Rawdon Crawley played cards to fleece his comrades.

However, this association may be a clue to understanding what is happening around the Macaulay twins in Book 2.

The parallel between Charles and Rawdon becomes more clear in retrospect, closer to end of the novel.

Both from respectable families but empty-headed, moneyless and dependent on relatives, they spend time drinking, gambling and screwing around. Both have debts — tend to be overly jealous — get arrested — get involved in love scandal with a rich rival — are ruined but ready to fight — end up in exile.

Yet, the only important thing here is Rawdon's relationship with his wife.

At her brother's elbow Camilla played the role of Becky Sharp in marriage with Rawdon: an attractive young couple that works in tandem, using their charm and wit to take advantage of wealthy friends, and exploiting affections of others to live a better life.

Francis gave some insights into this symbiotic relationship, describing it as 'they like to present a unified front but I don't even know how much they care about each other' (chpt. 8).

When Camilla abandoned this unified front, for Charles it was a betrayal as if she used to be his business partner, not just a lover or family member.

The most notable link to Becky is the role of Clytemnestra, performed by Camilla as well, and the symbolic meaning of it in both novels.

Like Clytemnestra, Becky Sharp is an archetype of a predatory female in disguise of false innocence. Strong-willed, cunning and bold, she’s a skilled actress and manipulator, still unable to predict the consequences of some of her actions.

At some point Camilla makes it clear to Richard that drunk Charles abused her, but Richard is surprisingly angry with her. He questions how Camilla got her injuries, because he feels that something's wrong (chpt. 8).

This situation looks quite peculiar in view of the analogy to Vanity Fair.

Camilla's counterpart, Becky Sharp, complained to her patron Lord Steyne that she experienced all sorts of injustice from Rawdon Crawley (VF chpt. 52). It sounds false, because Rawdon could’ve been a bully with other men, but with Becky he was a meek, submissive husband. All her complaints had only one purpose: to be pitied for her own benefit.

It's unclear to what extent this analogy works, but it may explain why Camilla wanted to put a distance between Richard and Charles. If she lied to Henry, or rather manipulated him, she wouldn't be glad to be exposed: just like in case with Bunny, Richard still was an alarm bell, the first person to whom the one can confide.

Thus she had to neutralise him. And thus she was unable to reconcile Charles and Henry later.

I dare say, Henry had seen what was going on, but he was glad to get rid of the third party in their love triangle anyway. Even Richard doubted his 'good' intentions.

Rawdon Crawley said about his wife: "if she's not guilty, ... she's as bad as guilty" (VF chpt. 55). It might illustrate Charles's point of view as well. Like Becky, his sister didn't want to bet on a losing dog. But even if Camilla had no evil intentions, the consequences of her actions were awful — she opened a Pandora's box.

According to Thackeray, “it is the unwritten part of books that would be most interesting”. And Donna Tartt used this principle full on, leaving all crucial events in shadows, but giving some hints to lead and mislead her reader through carefully constructed cultural references.

Which also can be just some Metahemeralism.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Julian invited Richard for lunch to talk about Bunny (chpt. 5), he served four-course meal with a bottle of ”maddeningly delicious“ wine:

At first I thought that Donna Tartt picked Château Latour for this scene to support the leitmotif of chess, since 'la tour' is not only a tower, but also a rook in French. And then I've seen this logo:

Considering the way this novel is constructed, there can't be any unintentional details, especially like this: a lion on top of a tower.

So, plus one big cat to all that feline fuss in TSH, popping-up out of the air like the Cheshire cat. Or like Henry Winter.

Cats in TSH are a symbol of Dionysian madness, lion in particular is one of Dionysus' sacred animals. And a rook represents relatively straightforward Bunny in this game.

A lion on a rook appears to be an ominous sign of Bunny's progressing madness and future death.

This wine was maddening indeed.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard & brooks

The word ‘brook’ appears quite frequently around Richard in TSH. It might be one of many allusions to Lewis Caroll.

In ‘Through the Looking-Glass’ Alice observed the Looking-glass land from above, and that’s what she saw:

A chessboard. Every rank ended with a brook, which Alice had to jump over for every move. Pawn-Alice passed six brooks to become a queen. As for Richard, there’re only five:

1. an old Brooks Brothers jacket, presented by Judy;

2. a book of the poems by Rupert Brooke, an excuse gift from Bunny;

3. Shady Brook, Bunny’s hometown;

4. “By brooks too broad for leaping the lightfoot boys are laid…” – line in the poem, which Henry read at the funeral;

5. Brooklyn, where Richard spent his summer.

That’s it for brooks, unless the last brook was hidden.

In the epilogue Francis mentioned the sherlockian Reichenbach Falls — der Bach is ‘brook’ in German.

And here I can’t stop thinking about this lil guy:

Presumably the screenwriters of Sherlock BBC were not the first ones who tried to translate ‘Reichenbach’ into English as Richard Brook. And this last brook happened to be fatal.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consummatum est.

These words appear twice in TSH: when Henry took a shard of glass out of Camilla’s foot (chpt. 2), and when Richard recalled Bunny’s murder (chpt.6).

Someone on web already mentioned that this line belongs to the sayings of Jesus on the Cross. Here’s an excerpt from wiki about it:

In both cases in TSH 'consummatum est' was an expression of triumph, but there’s more meaning to that.

In scene with Henry and Camilla the phrase might have subtle sexual subtext, as in Catholic church a word ‘consummatum’ was applied, inter alia, to consummation of marriage.

It seems, with Bunny it’s more about the paid debt. However, from Richard’s perspective that murder was something different. And, after years, he finally managed to catch this feeling in full.

I’m quite positive, when Richard used words ‘Consummatum est’ while remembering the murder, he referred not to the Bible, but to Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.

Faustus said it when he signed the pact with devil:

For mature Richard the murder was a Faustian bargain, which meant that he made himself accomplice to evil, bound himself into lifelong guilt.

So, even if 'consummatum est' is a word of triumph, it wasn't a triumph for Richard, it was a triumph of evil over Richard. And he knew it, eventually.

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julian & Thackeray

Richard mentioned that George Orwell compared Julian to a mirror:

This reminds of a famous passage from Vanity fair:

The world is a looking-glass, and gives back to every man the reflection of his own face. Frown at it, and it will in turn look sourly upon you; laugh at it and with it, and it is a jolly kind companion; and so let all young persons take their choice.

17 notes

·

View notes