Text

The Lone Star Express (The first chapter.)

I know I’m a bit of a tease, but here is Chapter One of The Lone Star Express!

CHAPTER ONE

Invest heavily in ammunition. That’s the flip-side of the warning on seeking revenge—the one about first digging two graves. When vengeance seeks you out—as opposed to the other way around—it’s wise to be locked, loaded and ready. But you have to know it’s coming, first.

With me it’s always something like that.

I’m Bill Travis, and apparently I’ve never met a problem I didn’t welcome to come on in and pull up a chair.

It began, innocently enough, with the performance of a good deed. Which brings up the second warning that I somehow bypassed during all the sturm and drang of Governor Richard Sawyer’s final disposition: no good deed goes unpunished.

Here’s how it started.

*****

Former Texas Governor Richard Donegal Sawyer was born in the Louisiana canebrakes back in the dark days of World War II. As an infant he was brought to the Texas Gulf Coast and raised by his father, his mother having died in childbirth. At age sixteen, or thereabouts, Sawyer and his father had a falling out over the fact of the elder Sawyer’s being a bloodthirsty killer and crime boss. The junior Sawyer’s feet carried him all the way to West Texas where he settled down at a life of hard labor as an oil field worker in the Permian Basin—Midland and Odessa. With his passing, at the ripe age of eighty, someone had to go looking for his will. I got that duty, at the request of his granddaughter, Elizabeth.

I was no more than a few days back from Mexico when she asked me. The next morning, I got up before the crack of dawn and drove Julie and a whole truckload of kids down to Houston, and stopped by the Sawyer home.

Julie rocked the baby in the rocking chair in Sawyer’s living room while Elizabeth and I commiserated at the dining room table, thirty feet away. There were a couple of banker’s boxes open on the glass tabletop and the contents—old papers, invoices, random things like insurance policies and old hospital bills—were poured into each box so tightly that both were apt to burst at the seams. I understood the filing system. It’s easier to throw it all in a box, especially after you realize that every single scrap of paper would need its own separate file, and office supply stores don’t typically carry fifty-thousand file folders. At least not in the economy pack.

“Do you mind?” I asked Elizabeth, and gestured with my hand over one of the boxes.

“Please do. I’m afraid to touch any of it. I’ll get immersed in it and won’t see daylight for days on end.”

I nodded and pulled out a thick sheaf of papers, about a reams-worth, and dropped it on the table-top. What spilled out was expired insurance policies, licensing agreements for trucks and tractors, old pay stubs going back to the 1950s and 60s, random photographs; a lifetime’s worth of the detritus of those things that, at the time, could not be simply thrown away. The things a person keeps!

“Yuck,” Elizabeth said.

“Everything here tells a tale,” I said. “If you were to piece it all together, maybe put it in chronological order, you’ve got a piece of the story of your grandfather’s life, which is another part of the story of Texas.”

“I know it’s not all trash, but some of it’s trash,” she said.

“No doubt. Okay, we’re looking for his will. And you say that it’s not tucked away in a safe-deposit box somewhere?”

“Uh uh. I cleaned those out. It wasn’t in there.”

“Then it’s here. Let’s keep looking.”

It took thirty minutes, but I found it. Oddly enough, it was fairly recent and tucked into the front end of the second box, right where you’d put something recent, if you were archiving it. The will was signed, witnessed and notarized roughly six months previous.

I began reading aloud.

“He leaves the whole kit ‘n kaboodle to you, Elizabeth,” I said.

“Let me see.”

I handed it to her and she read it to herself, her lips moving soundlessly and her eyes going back and forth.

“It’s a lot of responsibility for a woman your age. But I’m sure you can handle it.”

“There’s a list of stocks, bonds, all kinds of…”

“Financial instruments,” I finished for her.

“Yeah. Those.”

“It’ll take some time to find out what they’re all worth. No doubt the bulk of them were in the safe deposit boxes.”

“There was a bunch of that stuff in there, but I didn’t understand any of them.”

“I’ll take a look at them for you. For now, I suggest you get your own safe-deposit box and put them away. But after you make photo copies of everything. I’ll need a copy of it all, and I can get Penny at my office working on it in her spare time.”

“Ha. If she works for you, Mr. Travis, I doubt she has very much spare time.”

I chuckled. “You’re probably right. Never thought about it. She doesn’t know it yet, but I’m naming her a full partner on Monday.”

“Then she’s been paying her dues all these years.”

“She has.”

Elizabeth turned a page, moved her eyes down and then struck upon something. She frowned.

“What is it?” I asked.

“A heading: Disposition of Remains.”

“Oh. They’ll need to know about this down at the funeral home. And pretty quick. Before I left Austin, I had a call from the Texas State Cemetery. They’re expecting to bury your grandfather there. It’s where we bury our Governors.”

“Not according to this, it’s not.”

“Crap. I’d better see it. Those guys may have already set aside a plot for him.”

She handed me the will.

“You’ll need to get this filed with the Probate Court as soon as—” I began, but by then my eyes were already taking in the bad news. My own name jumped out at me from the page:

DISPOSITION OF REMAINS

Since I buried my heart in Midland a long time ago, it is my wish that my body be buried there beneath the ancient mesquite. I purchased the plot in 1969, knowing full well that men can easily lose their lives in the oil patch. Further, I request that my friend Walter M. Cannon accompany my body by train to its final destination. If Walt Cannon predeceases me or, due to issues of health or availability, is unable to fulfill this wish, then I request that my dear friend, Bill Travis, should do so.

For many years I have been a supporting member of the Big Thicket Steam Association, headquartered in Palestine, Texas. I request that those old boys—those who have survived me—get the old ‘19 running for one last trip out west, and that I travel each mile between Austin or Houston and Midland by whatever rail line the boys may take. I pray that I may find my rest there in Midland.

“What’s the ‘Old ‘19′?” I thought, then realized I had said it aloud.

“I have no idea.”

“It’s okay. Tell you what, why don’t you ride with us down to the copy store where we’ll make three or four copies of this, then we’ll scoot by the funeral home, drop this off with the director and let him know how to contact me.

I detected a presence at my elbow. It was Julie, gently bouncing the baby.

“What’s going on?”

“It looks like I’m going to West Texas.”

“When? And how?”

“Soon,” I said, thinking all the while about bodies, temperature and steel boxes. “And by train.”

*****

I took the family back home to Austin after making certain that everybody on the Houston end of things was on the same page. The plan was for Governor Sawyer’s body to be transported to the State Capitol, there to lie in state for two days time where all Texans who wanted to might stop by and pay their respects. It’s a time-honored practice, and Sawyer’s will didn’t preclude it. I’m not certain it would have done any good if it had. In the final analysis, while we may suggest what should happen after we’re gone, it’s the family’s wishes that are usually honored, and at any time those wishes may be trumped by the state, particularly in the instance of a dignitary. In the end, we all render unto Caesar, right down to the toenails.

In the meantime, I had a ton of phone calls to make and correspondence to get out in preparation for what was to come—an event to which I was decidedly not looking forward.

I spent an entire day at the office, mostly listening to and receiving updates on Penny’s progress on the stocks and bonds.

At the appointed time—pre-arranged between my partner and me—Nat Bierstone came by the office. He was dressed in a blue jeans, red checkered shirt and suspenders. Penny gasped. She had never seen him in anything other than a business suit.

It had been three weeks since he had come by the office. Both he and I knew that he had already retired, but he was in to make it official.

“Mr. Bierstone, you look like…a real person!” Penny said. I listened from my office, having already glanced out my window when Nat pulled into circular driveway that runs behind the office and out the other side.

“Why thank you, Miss Taylor. Is Bill in? Thought I saw his car.”

“Come on back, Nat!” I called. “Penny, you come in here too.”

I waited. When they were both inside, Nat reached behind him and closed the door.

“Something is happening, isn’t it?” Penny asked. “Are you two about to fire me?”

“In a manner of speaking,” Nat said. She started to protest, but he raised a finger, then gestured to one of the two chairs in front of my desk. “Hush now and have a seat.”

“Yes sir,” she said.

Nat took the other chair, and by way of stretching the moment out interminably, fumbled in his blue jeans pocket for the front door key and the key to his office. He removed them from the key chain and said to Penny, “Hold out your hand.”

She did, and Nat placed the keys in it. “Don’t lose them until after you’ve made another copy. This is the only one to my office in existence.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Nat’s retiring,” I said, “effective today.” I picked up an envelope from the counter and handed it to him. He took it.

“What is that?��� Penny asked.

“A check,” I said. “I just bought Nat’s half of the business.”

He looked at the envelope, poked a finger at the inside of the crease, as if he was about to open it with his finger, then instead handed it to Penny.

“You want me to open it for you?” she asked.

“I want you to keep it,” he said. “You can do whatever you want with it, since it’s yours.”

“I—I’m not sure what you mean.” Her voice trembled and had become very small.

“You know what it means,” I said.

“Let me do this, Bill,” he said. “I’ve earned the right.”

“This is where you fire me,” Penny said. She opened the envelope delicately and removed the check. The amount was eight hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Her eyes stared at the thin slip of paper.

“She’s gonna burn a hole in it,” I said.

“You can keep that and cash it,” Nat said, “or you can give it right back to Bill, keep that key of mine, and start worrying about who is going to replace you and become your secretary. Or rather, yours and his.” He hooked a thumb at me.

She looked across the desk at me. “How much is half the practice worth?” she asked me.

I laughed. “Spoken like a true accountant and financial consultant.” I leaned back in my chair and interlaced my fingers over my head. “Worth a hell of a lot more than twice eight-fifty.”

Penny handed the envelope back to me. “Then I suppose we’ll need to start interviewing applicants.”

I stood up and extended my hand.

“Welcome to Travis & Taylor,” I said. She stood slowly, then took my hand and shook it. And then she started crying.

Nat stood. She let go of my hand and threw her arms around his neck, her face disappearing from view. Nat grinned at me and patted her back.

When she released him, she stood and wiped the tears from her eyes, then slowly handed the check back to me.

“Go ahead and re-deposit it in the practice account. And make an appointment at the bank. You’re to be signatory to that account from now on, so consider that you just paid yourself back.”

“Who’s idea was this?”

“All three of us,” I said. “Nat, me, and Julie as well.”

“I wish she were here.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “She made me promise to give her the play-by-play tonight.”

“I don’t know what to say,” she said.

I laughed. “There’s a first time for everything.”

“I’ll try to be a good partner for you, Mr. Travis.”

“Penny, now that it’s official, you are required to call me Bill. I won’t have a partner who can’t say my name.”

“Mr. Bierstone calls you William.”

“He can get away with it because he’s older than I am, he’s the former Lieutenant Governor of Texas, and worse than that, he’s Julie’s uncle.” I grinned at her. “You can’t.”

“Okay, Bill,” she said. And you could have knocked me over with a feather.

0 notes

Text

Antarctic

Just a little bit on this Antarctic story:

CHAPTER TWO: THE SHELF

The Antarctic

September 16, 1888

The Invincible lay at anchor before the blue and white cliffs. The first rope, attached to Gomez’s harpoon, was fired up and over the ice shelf by the twelve-pounder prow cannon—which equipment was the last vestige of her fighting past, but which the navy could not easily remove from the prow emplacement before her auction—and the breathless spectacle of watching Manuel Ortega shinny up the rope with three other rope bundles and an additional forty pounds of steel spikes bound about his form made for the single-most riveting moment for the passengers and crew during their brief voyage from The Falklands, apart from the bloody taking of the narwhal the previous day. If the harpoon, embedded somewhere above in the implacable ice, were to give way, then Ortega’s fifty-foot climb would be his last, this everyone knew.

When he disappeared over the cliff’s edge, a cheer went up.

“Hurrah! Ortega!”

“Mr. Gleese,” Captain Kuralt stated, “you and your men may now disembark, and with my compliments.”

“Thank you, Captain,” Gleese said, and shook the Captain’s hand. No wind blew here beneath the cliffs of ice, and as the cheering about them ceased a silence stole like death across the deck as the men returned to their work.

The cargo hold was thrown open and the supplies were hoisted forth.

Mr. Kroones—Gleese’s Danish dogman—led the pack up from the stern stairs and onto the deck. The pack was composed of a mix of grey Huskies, white Lapps, and black Alsatians—and it was a marvel that Kroones somehow kept them all from tearing one another to pieces. At night the man sang them to sleep, his melodious and nearly falsetto voice reverberating off the interior of the hold as if he were in some grand Opera house. Kroones waved to Gleese and Gleese nodded. Kroones and the dogs would be first up onto the ice after Ortega.

“You’ve marked the coordinates well, then, Captain?” Gleese asked.

“Yes. Hmph. We’ll see you here on December fifteenth, sixty-nine degrees, fifty-fourth minutes, forty-nine seconds south by sixty degrees, twenty-nine minutes, fifty-five seconds west. And Godspeed, Mr. Gleese.”

“Godspeed, Captain. I shall reach the pole and return.”

Kuralt nodded, but did not speak further. He had meant to say, “See that you do,” but he could not bring himself to tempt the Fates, or otherwise put voice what he felt in his chest—a disquieting foreboding, much like the coming onset of some malady that might prove a challenge to the doctor, if not to the clinging hand of life itself. Instead, he turned his eyes from the already tired explorer, placed his hand on the railing and gazed down upon the men at work.

*****

Twenty-five men and forty dogs watched as the Invincible belched steam. Her whistle blew a shrill goodbye as two sets of men who had been intimately intermingled for the past week waved to each other across the Antarctic air.

“Let’s move a bit towards land, shall we?” Gleese stated. “I wish to be away from these cliffs before we make camp for the night. Mr. Tomaroff, how far off is the land mass, would you say?”

“Fifty kilometres, no less,” Micail Tomaroff said. Tomaroff opened his pocket watch, then glanced up at the southern stars, as if confirming his calculations—a nod to the seemingly arcane science of celestial navigation. The sun was on the horizon, and would not quite disappear below it for several months to come, or at least not until the Antarctic fall, which would commence sometime in February, long after they were scheduled to depart this desolate and forbidding land.

“Very good. Mr. Kroones, please prepare the sleds for travel.”

“Sehr gut, Herr Gleese.”

Danish, Russian, Spanish and Portuguese were four languages that Gleese had not learned, or at least not well enough to carry on a conversation beyond an exchange of idiotic pleasantry. He could read Latin, some Greek, Gaelic, Chinese and Nipponese, and could speak some pidgin of the two Asian dialects—which was necessary in the far away Arctic—but English was his native language. While the language of Tennyson, if not of Chaucer and Mallory, was his favorite reading, he was forever mentally tethered to the American dialect of New England; that of Washington Irving and Thoreau, of Thomas Paine if not Thomas Jefferson, was how he best thought. That few of his own expeditionary party could converse with him intelligently could ultimately prove costly if luck refused to hold, as Kuralt had pointed out to him when the Argentinians had signed on en masse, lured as they were by the legendary weight of Gleese’s purse. He had largely and single-handedly depopulated the Falklands of male Argentinians, and all for filthy lucre. Some might die during the expedition, particularly if they did not heed the regulations—no wandering away from camp solo, even to relieve themselves, and not without rope.

The most dangerous foe, if it were not the ice and the wind itself, was the stealthiest, most hidden quarry imaginable; that of crevasse. He had personally witnessed a man swallowed whole by an opening in the ice that had not existed a moment before. Swallowed so utterly and completely that it was as if the man had never existed. And it did so even more abruptly than a cry could escape the lips.

No. He would not allow this to be. He resolved to spend a portion of time each evening learning Portuguese, Danish and Russian.

0 notes

Text

Craypipe and Stovelilly

I don’t know what this is, nor where it’s going, but…hmmm…here it is:

Of all the tales of great adventure that come down to us from the old days and the older ways, nary a one is any more moving, any more adventurous, nor more affecting than that of Craypipe and Stovelilly. As you all know, Craypipe lived in the Wide Valley and Stovelilly kept her abode up in the Laurel Range of the Saw Teeth, and only upon great peril would Craypipe adventure forth from his shack among the stands of paper reeds; but the weather was fine and Craypipe was still young and less set in his ways, and he wondered what sort of land lay beyond those far, high and jagged peaks, and as you well know, there is no stronger motivation than simple curiosity. So one clear and bright morning, after all the chores had been done, Craypipe cursed to himself, threw up his hands—those hard hands were already gnarled with great strength and abrasive and harsh toil, even then—and put a paper note on his door saying, Gone Explorin’, put a blanket and one of his old belts around the mule, put some crackers, cheese and jars of honey wine in his burlap sack, grabbed his stick and set to walking.

Now, as you also know, Stovelilly got her name on account of her odd birth—her mother, Pratelin, was cooking that day for the Savior Man’s Feast and all the extended family in the hills, and the babe chose that precise moment when two or three things were ready to come off the stove or out of the oven all at once to come into this screaming world. Pratelin felt Stovelilly start to drop and reached down in a flash and caught her by the foot, lifted her up and set her in the cooking pot on the back of the stove—there was no fire under that burner, don’t you know, because it was nothing there but water for cooling things down with—and the new babe settled into the cool water, looked up at her mother and smiled. In the next instant, Old Ames came into the kitchen, took one look and stated, “Now Ma, what you cooking over there on that corner? Because I don’t think the folks will want any of that!”

“Oh shoo!” Pratelin said, damping down the fire under the taters. “That’s nothin’ but my little stove lilly.” And as you know, the name stuck.

But that was a long time ago, close on to thirty years, and Stovelilly lived in the cabin perched on the saddle of land between the two valleys all alone. Old Ames had died of white rot and Pratelin got herself struck by lightning—and that is a whole other story, let me tell you—and it’s a hard world when you’re living on your lonesome. The family didn’t bother to come and state when they were moving off to the valley. They had forgotten about Stovelilly, as people sometimes do when they are deeply involved in their own affairs.

Now there was still magic in the Earth in those days. Some believe that it originally came from the great volcanic vents in the ocean, mixed with the water, was skimmed from the waves by the great winds that blow unceasing, and was dropped upon the mountains in great rain deluges, and ran down across the land and found its way into the very crops and the animals that we eat. It didn’t, then, take a lot of magic to manifest itself in ordinary ways such that no one thought of it as being quite…magical. They will see a tree growing from a little nut and think nothing of it, or a water spring up from a rock and pass it off as simply the way of the world. But it takes magic to move things, to cause them be when they weren’t before, and to generally bring forth life and living.

However the magic came to be there, it so happened that Stovelilly was particularly sensitive to the ways of magic. She saw it everywhere around her, and was quite versed in pushing it along, of spreading it around such that little things throve and grew in profusion near her. Consequently, the saddle of land between Laurel Mountain and Forrestal Peak became ringed with a great forest of birch and pine, black walnut and maple, and fruit trees were everywhere such that there was no need to plant any crops nor slaughter any animals—for it wasn’t in Stovelilly’s nature to kill anything that could gaze upon a sunset or grow tired or thirsty. Thus, she walked alone in the forest, singing songs to herself to bide her time, and wondered as she walked if she would ever hear the voice of another human being ever again.

She had no way of knowing that a human being would be coming to visit her, and very soon. The magic didn’t speak of it, and her Dream Spirit kept the secret of his coming, for if she had any inkling of what would thereafter occur, she might have blanched at the aspect of it, and hidden herself, and not answered when the call came, borne of the wind that blows about the misty peaks in the morning.

It was seven days for Craypipe from the morning he left the shack until he came to the foothills beneath Laurel Mountain. He spent much of his time talking to his mule. The mule listened, but to his credit didn’t talk back. Nor had Craypipe ever named the beast, other than to call him, properly, Mule.

When Craypipe laid his head down that last evening before attempting the peak, he looked up at the stars and saw that they had not changed one iota from where they were back home, and he wondered at this. He had always heard that the stars were different in the southern climes. This, from the tales of old explorers, handed down through the years. But those old explorers had great boats, and all he had was an old mule who couldn’t talk or even curse back at him. Maybe it was all foolishness. How could the stars change?

0 notes

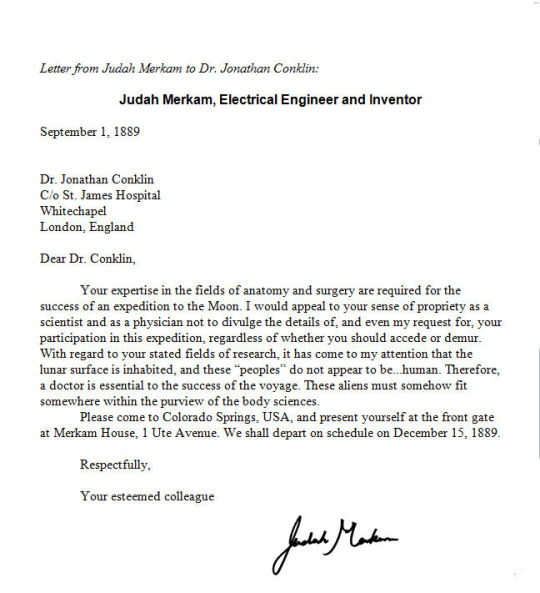

Photo

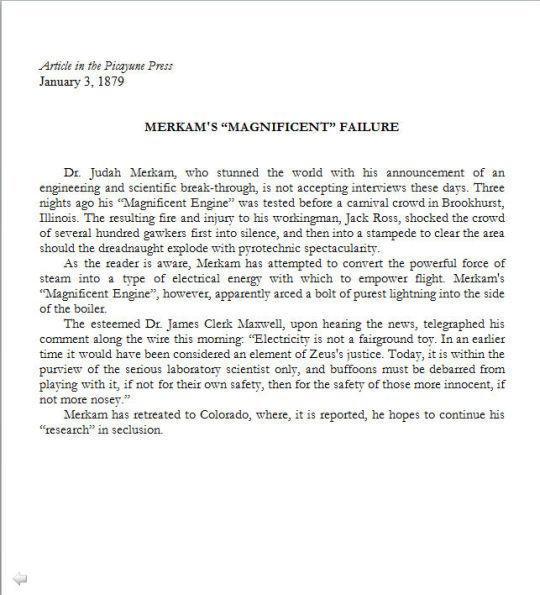

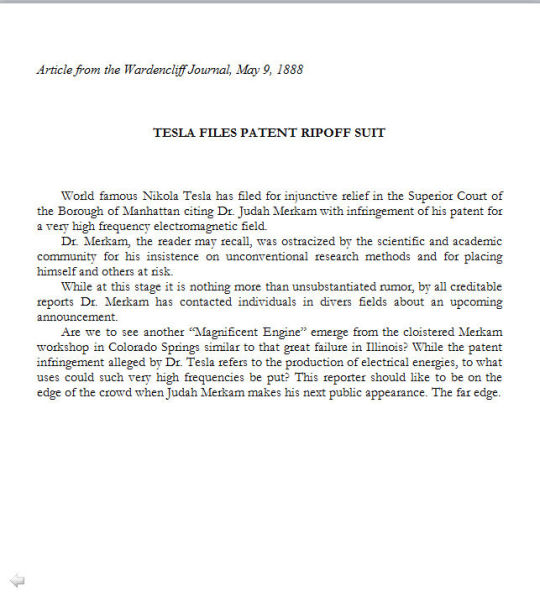

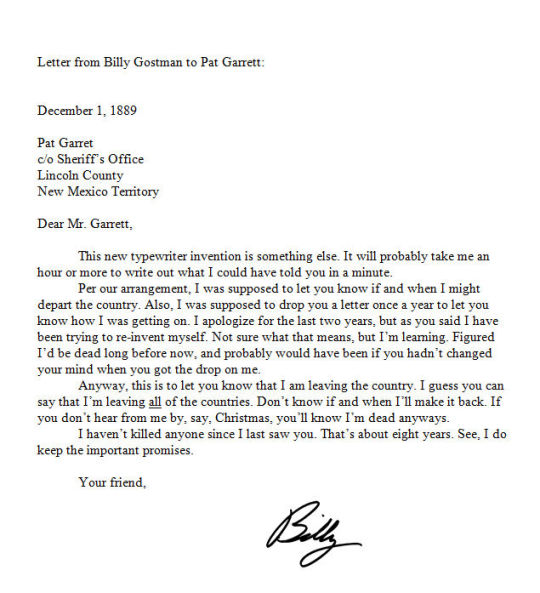

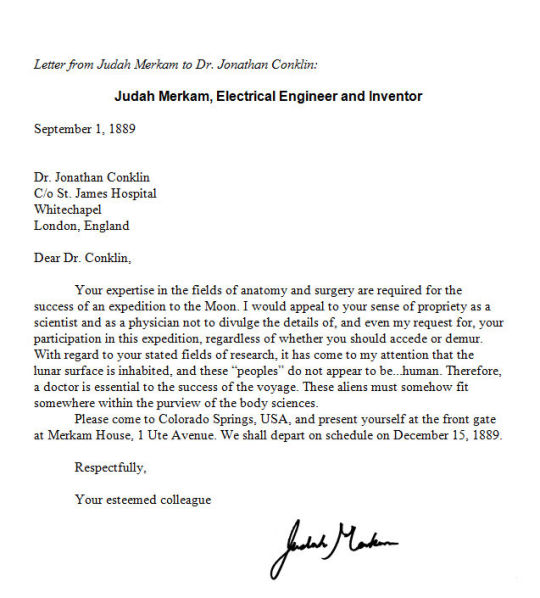

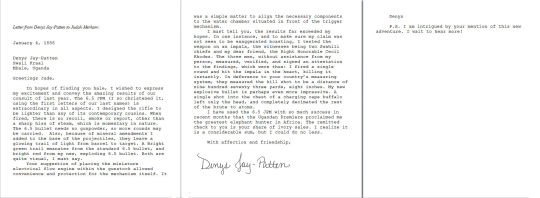

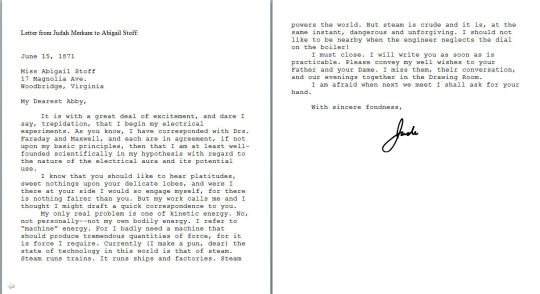

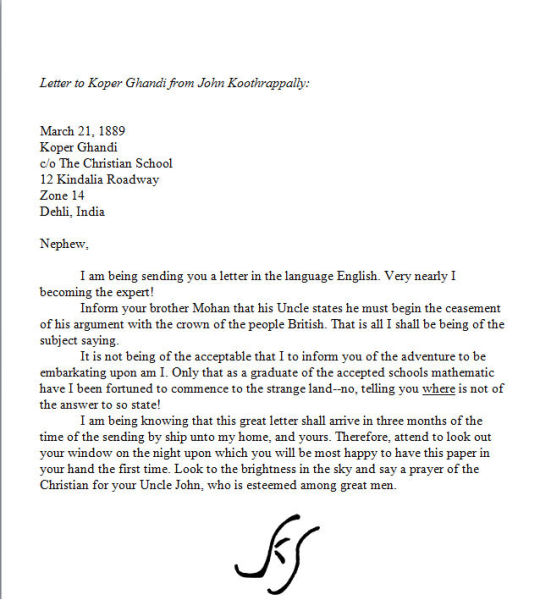

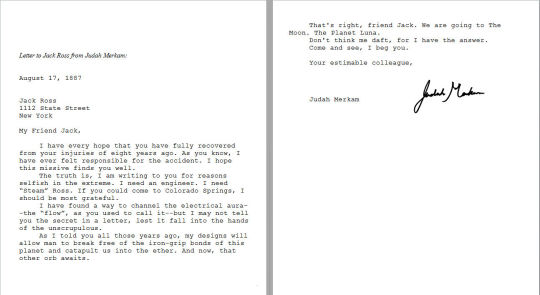

Letters and articles from 1889: Journey to the Moon

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Watchers by Milton T. Burton

Here's a short story, penned by Milton T. Burton, that about summarizes my attitude for this day. I hope you enjoy it.

THE WATCHERS

Milton T. Burton

I was coming out of the Wal-Mart Supercenter yesterday when an earnest-looking fellow who appeared to be in his mid thirties came up and tried to hand me some kind of lurid religious tract.

"I can't accept that," I told him.

"Why not?"

"I'm an Alpha Prime."

"Huh?" asked in obvious confusion. "Alpha what?"

I decided to take the time to explain it all to him. "Prime," I said. "Alpha Prime. Surely you know as well as I do that there are only three types of people in this world. Alpha Primes, Control Agents, and Subsidiaries."

"Subsid. . ."

"That's right," I replied. "And I know you're not an Alpha Prime because we always recognize one another. And you don't look focused enough to be a Control Agent, so it's pretty obvious that you're just a Subsidiary."

For some reason he seemed to find this mildly alarming, so I moved in closer and put my arm around his shoulders and gave him a reassuring squeeze. "You see," I said, "the sole purpose of Control and its agents is to keep us Alpha Primes from detecting the Pattern. That's the reason they try to annoy and distract us as much as they possibly can. But I'm onto them."

"You are?"

"Right," I said, giving him a conspiratorial wink. "I became aware of the Pattern a long time ago."

"The Pattern?"

"Right again. Let me give you an example. I'm sure you've seen that insurance ad that features the British rock guitarist, Peter Frampton. . . Right? It's on TV all over the country."

He gave me a hesitant nod, and his eyes were growing ever wider.

"Well, surely you realize that there is no such thing as a Frampton."

"No?"

"Absolutely not," I said firmly. "Can you imagine anything more absurd than a Frampton? I mean, have you ever actually met one yourself?"

He shook his head. "No, I can't say that I---"

"Of course you haven't. You see, the Control Agents just gave that guy the name because they realize that 'Frampton' is one of those words that we Alpha Primes are genetically predisposed find utterly loathsome."

Here I stopped speaking and gave his shoulder another squeeze and then continued in a knowing whisper. "And if we're all bent out of shape about 'Frampton,' then we're sure as hell not going to notice the Pattern, now are we? And that's any Control Agent's whole purpose in life. Obscure that Pattern. Get it?"

"I, I'm not sure," he said dubiously. "But I really have to go."

"But you haven't given away all your tracts."

He shrugged. "I haven't had much luck here, anyway."

"Luck?" I asked. "Why, my friend, there's no such thing as luck."

"No?"

I shook my head gravely. "Of course not. There's only the Pattern. For example, have you ever been about ready for bed and then realized you just had to have a soft drink or something? So you find yourself dragging your shoes back on and driving a couple of miles to the convenience store and dealing with some Pakistani idiot who can barely make change. That's because you had to be in a certain place at a certain time, either to cause something or to prevent it. A car wreck or whatever."

"Well, I. . ."

"No doubt about it," I said and gave him a resigned shrug. "The grim truth is that we're all slaves to the Pattern, whether we realize it or not. Even the Control Agents. But you should be grateful that you Subsidiaries only get the small assignments. We Alpha Primes get the big jobs. Why, I once had to fly all the way to Budapest and eat a liverwurst sandwich in a certain café to prevent a dormant volcano from blowing up in Iceland. And I hate liverwurst."

At this he bolted and sprinted to his car and then sped quickly from the parking lot. No doubt he was eager to fill his friends in on what he'd just learned about the Pattern. I regretted that I hadn't been able to tell him about the Watchers, but there'd be plenty of time for that later on. I'd memorized his license plate number, and I have a helpful friend in motor vehicle registration.

It was a lovely day.

0 notes

Text

First Chapter of Cold Rains

Here’s the first chapter of COLD RAINS:

[ 1 ]

My daddy always used to say that no good deed goes unpunished. He also used to say that looks can be deceiving. Put those two together and I believe he would have seen right through Melissa Sossville had he known her. I know I did.

I was in Bud Parkins’s office when Sossville’s old man came through the front door in search of a bail bondsman. That’s what Uncle Bud does—bails people out of jail. But unfortunately for Bud, he didn’t have either my daddy’s or my own powers of observation when it comes to people or he never would have advanced a quarter of a million bucks to get Miss Sossville sprung. Instead of turning the old man and his little girl down flat, he went ahead and handed the Sheriff’s deputy a cashier’s check for a quarter mil and waited around for twenty minutes in the booking room while someone rode the elevator back upstairs and fetched her. I should know, because I was there the whole time, looking things over, watching and waiting. Bud wouldn’t look at me. He knew where I stood, and he didn’t like me being in the middle of his business. Except I had to be there as part of my agreement with his company.

I’m Jim Rains, and I’m a bounty hunter.

But let’s back up here. When Sossville’s old man came through the front door of 911 Bail Bonds, he spilled a pint of water from the brim of his hat onto the welcome mat inside the door. It had been raining in Austin and across most of Central Texas for the last two days, and having just come off of one of the worst droughts in the State’s history, the rain was certainly welcome. What wasn’t welcome was the face of the man under the brim of the straw Stetson. It was a face that was so used to seeing tractor-trailer loads of misery and defeat that he must have decided to invest heavily in the stuff. The seams in his face had cracks running across them like the surface of one of the ice moons taking its turn going around the planet Jupiter. His eyes were red like he’d not had a wink of sleep for years on end and had instead closed off the wide-awake portion of his mind to wait out the insomnia in earnest—along about 1980. Probably he drank half a dozen cups of coffee a day—with possibly a jigger or too of Tennessee whiskey stirred in for good measure—and smoked four or five packs of cigarettes. When the door opened and revealed his drawn and careworn face, the smell coming through the door wasn’t that of rain and ozone from the lightning show going on outside, but was instead the brutal odor of collected and dead cigarette butts from an old pickup with ashtrays brimming. By the way he moved I pegged him for not a day over fifty-five. I loved the son of a bitch immediately.

He looked at me, meeting my gaze with those red eyes.

“I need someone to bail my little girl out of jail.”

I hooked a thumb in Bud’s direction.

Bud is big man. That’s a nice way to say it. Bud’s waist size is close on to sixty inches, and let me tell you, not all of it’s fat. The man stands six-foot-one, and there’s a betting pool among the courthouse crowd as to how much he weighs. I’ve known big people before, and I’d say Bud weighs in a little over 475. Bud is nearly twice my age—almost sixty—and sports a buzz cut that leaves a sprinkling of black among the gray. I imagine that in order to maintain that constant buzz cut he measures upward from where the follicles emerge from his white scalp and puts the setting for his electric shears a micron higher than that. I have suspected for years that he runs the razor through his hair every Monday morning before coming to work. Bud doesn’t own a pocket comb, and disdains men who do.

“Come on in,” Bud said. “What’s your daughter’s name, and what are they saying she’s done?”

“Sossville. Mellisa Ann Sossville. They say she tried to kill somebody. I know my daughter. If she’d wanted to kill him, the fellow would be stone dead.”

While the old cowboy took a seat across from Bud at his desk, I looked up at the ceiling as if it was suddenly interesting. Bud ignored me.

“What’s your name?” Bud asked him.

“Erran. Erran Sossvile.”

“How much is the bond?”

“Two hundred fifty-thousand.”

Bud whistled. “When’s her trial?”

“How the hell should I know? I got the call in the middle of the night last night. Come to find out she’s been in there two days. I didn’t know or I woulda been here sooner.”

“It’ll cost you twenty-five thousand to get her out. Can you cover that?”

The man paused and removed his hat from his head. He was mostly bald underneath it. “I can cover it. It’ll set me back.”

“I don’t doubt it. The twenty-five is completely nonrefundable. You’ll never see a dime of it again.”

Erran Sossville nodded.

Bud thrummed his fingers on his desk for a few additional seconds, like he was tapping out the last measures of a piano tune, then said, “Tell you what. I’d like to meet her, first. You think she’d be up for that?”

“Why?” Sossville asked.

“Because. First of all, it’s company policy. Second of all, I wouldn’t bail out my own son without taking a look at his condition.”

“I just came from there. I’m telling you, she looks fine.”

Bud nodded. “Still. I have to do it. It doesn’t cost a cent more.”

“Shit,” Sossville said. “Okay.”

*****

By the time we got outside, the rain had slackened enough that we weren’t drenched until we were halfway across the street. The Travis County Criminal Justice Center looms five stories high above San Antonio Street in downtown Austin. Visitors have to go in the front door of the place and go through red tape to be able to see anybody. Bail bondsmen and bounty hunters, however, function ostensibly as officers of the court. While technically we’re not peace officers, the functionality of the criminal justice system demands we have access to the jail. Therefore, after crossing San Antonio, we stepped across a narrow strip of grass to the sally-port of the jail and were buzzed in by one of the booking officers, who saw our faces more often than we saw our own in our bathroom mirrors.

I didn’t tell you that I used to work for Bud. That’s how I got my start. Nowadays we’re more or less partners. He bails ‘em out, and I go and pick them up when they don’t show up in court at the appointed date and time. I didn’t like doing it when I started out. That first time was pretty rough, and maybe I’ll tell you about it sometime, and while the amount I was paid wasn’t nearly enough for all the hell I had to walk through to deliver, it was yet enough to bring me back for seconds. All by way of saying that I had it all calculated out before my boots hit the rainsoaked street: the twenty-five thousand that Sossville would have to pony up would go into a non-interest-bearing account, and if his daughter didn’t show up for her appointed court date, the twenty-five thousand was the bounty. That’s all that ten percent is, really. It’s a surety to the court that the accused will appear, and if they don’t, the bond company’s two-hundred and fifty thousand is forfeit until someone like me makes them appear. And that’s about the whole computation. Well, most of it, actually. Bud and I have a little side agreement that we split the bounty, me receiving seventy percent and him thirty. It’s not a bad racket. I get by on it.

I knew something was wrong when Bud gave Lance Boscum Sossville’s daughter’s name and the man looked from Bud to Sossville and then to me and his eyes did this little flicker thing. Lance can be downright tight-lipped about things, but I read a whole book in that faint flicker.

Lance nodded, turned his head left and called out to Ben Cooley, “Sossville. Bring her down.” Then to us he said, “You fellahs can have a seat if you’d like. Be about ten minutes.”

There are a couple of chairs available in the Travis County Jail, but none that I’d care to sit in. Bud demurred and Sossville—who looked as though he needed a bed far more than a chair, and a few months in close company with it at a minimum—shook his head slowly.

Ten minutes, my ass. It was twenty minutes if it was two. I don’t wear a watch—hell, I don’t carry a cell phone around either—but I have a good sense of time passing on by.

When Melissa Sossville emerged from the elevator wearing an orange jumpsuit three sizes too big for her and her delicate little hands in chains, I knew there would be trouble. She couldn’t have been more than a hundred and five pounds, even with the five pounds of iron on her hands and around her ankles, and the chain from waist to floor between them. She had startling blue eyes, straight dirty dishwater blond hair, freckles like a cornhusker’s dream of heaven, and a little upward lilt at the corners of her delicate mouth that bespoke of devious plans and intentions left forever unsatisfied. Even in the oversized orange county issue, I knew what she looked like underneath. She was young, she had not an ounce of fat on her, and she was a hellion. I wanted to keep her. We always want the bad ones, don’t we?

I could see right off that Bud was undone by her.

“Miss Sossville?” he asked her.

She nodded, and looked up at him with the eyes of utter innocence.

“They treating you okay, Punkin?” Erran Sossville asked his daughter.

“I’m okay, daddy,” she said. “Really.”

“Me and this fellah are gonna get you out of here,” Sossville said.

“Daddy, we can’t afford it. I’ll ride it out. I’ll be fine. I promise.”

Melissa Sossville hadn’t so much as glanced my direction, but still I was aware that she was fully cognizant of the gaze of every man in the room. She didn’t have to look. She knew. This was her stage and she was in the starring role. And bit players be damned.

Bud Parkins turned to Lance Boscum across the booking counter. “The charge, and the bail?”

“Attempted murder. Quarter million.”

“Drug screen?”

“Hold on a sec.” Lance punched away at his computer screen for a minute, seemed satisfied when the correct thing came up, then swiveled the monitor around for Bud to see it. “Negative tox.”

“Priors?”

Lance swiveled the screen back for a moment, tapped a few buttons, and then came up with a screen that had only two entries, from where I could see.

“Huh,” Bud said. “Both juvies. Okay. Thanks, Lance.”

Bud turned back to gaze down at Melissa Sossville. “What happened in court? Did you do or say something to…tick off the Judge?”

She shook her head slowly. “I didn’t hardly get a chance to say anything at all. I still don’t understand it.”

“Which judge?” Bud asked, as if the answer to this question could potentially explain all miscarriages of justice since time immemorial.

“I don’t remember her name,” the girl said, and then her voice trailed off, as if she were lost and forlorn and trapped in a vast maze with no apparent way out.

“Her. Had to be Martinez. Okay, we’re going to get you out of here. It may take us an hour or two, but we’ll get you free. Then you’ll have to come across the street and we’ll finish all the paperwork up there.” I knew what that hour would entail. Bud would take Erran Sossville to his bank, wherever the hell it was, and stand there while the man withdrew the twenty-five thousand. Then he would bring him back to the office and get him to sign it over to him on a dotted line. Along with the money would be numerous indemnity clauses, and an agreement to assist in making sure the girl met her court date. It was all pretty much folderol, and meant less than nothing.

The girl turned to her father. “Are you sure, daddy?”

“I’m sure. You’re coming home.”

“But I…” and then the crocodile tears came, and even I was moved by the seeming sincerity of them. I say “moved,” but no more than any man is moved by a woman’s tears. I wouldn’t have ponied-up twenty-five thousand bucks for the right handkerchief to dry them with.

Sossville stepped forward and the jailer accompanying the girl started for a second before recovering. But the old man wrapped his arms around the girl and hugged her tight, rocking her back and forth as if she was an eight year-old child.

“It’s okay, Punkin. It’s okay. It’ll all be better soon.”

Bud and I watched. Hell, there were six men in the booking room watching, all told, but none of us had the power to stop the reunion. Finally, Sossville let go of her. He held her at arms length, his powerful hands on her delicate arms.

“We’ll be back in a bit. Don’t you fret none.”

Melissa Sossville nodded. She turned and slowly trudged away, her chains rattling.

Bud then looked at me, his eyes searching. Sossville was turned away, watching his daughter as she stepped back onto the elevator.

As Bud’s eyes bored into mine, I did the most damning thing I could possibly do. I shook my head slowly. No.

His face sagged for a moment. He tilted his head and his eyes narrowed, as if suspicious of something.

I suppose my eyes widened in disbelief. I quickly shook my head again. NO!

He shook his own head then, the tiniest of motions, but in negation of my own negation. And that meant everything. It meant, “Yes.”

And so goes the story of men, ever the effect of a woman.

But not this man.

[ 2 ]

Well, maybe this man, too.

0 notes

Text

First Chapter of Captain’s Malicious

It is my firm belief that Captains Malicious is one of the best science fiction/space opera books ever written. I’m rather proud of it, since I’m one of the co-authors. Also, my hat is off to TR Tom Harris for his excellent writing. Here’s the beginning of the book, a hefty portion of Chapter One:

CHAPTER 1

Captain, I don’t like this,” said Commander Javon Steele as he hunched over the proximity screen, shielding it with his body from the glare of the lights on the bridge. “It sure looks like a six-master. I’ve heard rumors of one prowling around, and this could be her.”

“And you don’t think we can take on a little six-master?” Captain Robert Kincaid asked with a smile. He remained seated in his command chair, knowing that joining his Executive Officer at the screen might be read as panic and negate the air of confidence he was trying to convey to his bridge crew. He could tell by their fidgeting and furtive glances that they were growing nervous knowing full well that if they could detect the other ship, then the alien warcraft could detect them as well. And if this was the rumored Vixxie DN-Z then trying to outrun her would be a waste of time. Their fate was sealed the moment the image on Steele’s screen resolved clear enough to show the gravity signature of the powerful starship, along with her six deadly dots of light.

Steele left the proximity screen and went to where his captain sat, with legs crossed and appearing completely at ease. The tall, slender black man leaned in close so the others on the bridge couldn’t hear.

“Robert, we cannot go up against a ship that big. I know it, you know it…and so do they,” he lifted his hand to indicate the remainder of the bridge crew.

Kincaid kept a placid smile. “Your look of absolute dread isn’t helping things, Javon. The crew is scared enough already.”

“This is serious, Captain,” Steele said, growing frustrated. “And by the way, you ain’t foolin’ nobody. Everyone knows we’re in some deep rhino dung when you start wearing that goofy grin. They’d feel better if you were the irascible, top-deck-dictator you normally are.”

“Dictator! Dammit, Javon, I’m a captain, not a dictator.”

“Six of one….”

Kincaid took a deep breath and let the smile fade away. Shedding his fake countenance made him feel better since it was so out of character for him to mask his feelings just for the sake of his mostly-rookie crew. And his XO was right, it did betray the seriousness of the threat they faced.

There were a total of twenty-two men and women aboard the Malicious, with eight on the bridge, including himself and Steele. Since going to General Quarters, the tension within the ship had notched up palpably. The remainder of his crew were either nervously sweating it out at weapons batteries or sat huddled in passageways with damage control equipment at the ready—just in case. The news of the possible six-master was no doubt spreading rapidly.

Robert narrowed his focus on the forward viewport. The enemy ship was out there still light-years away, yet it represented the gravest threat his crew had ever faced—and everyone knew it. It was now time for some serious captaining. After all, one didn’t sit in this chair because you knew how to coddle a crew. You sat here because you knew how to survive.

“Helm, bring us to one-eight-zero degrees, down fifteen, all ahead flank.”

Steele backed away from the command chair and gave his Captain a nod.

“The Drift Current?” he asked.

“Yep, the Drift Current. If this does turn out to be the Vixx’r forty-gun dreadnaught then she hasn’t been in the Reaches long enough to get a lay of the land. We just may catch her off-guard.”

“It’s worth a try,” Steele said. “Seeing that we’re all going to die otherwise.”

“Have faith, Number Two. Besides, they’re going up against the Malicious. They may be aliens, but they can still shit bricks, and I’m sure that’s what they’re doing right about now.”

“Target tacking to starboard, sir,” Lt. Sean Sinclair reported from tactical.

“They’re coming after us, Captain.”

Kincaid noticed the sudden attitude shift on the part of the bridge crew—the abrupt passage from uncertainty to a resolve to carry on. This was what these people had trained for—even if hastily and mainly on-the-job. Yet already his young crew had four successful raids under their belts, and with each they’d gained proficiency, experience, and most of all, courage. Of course, none of their other prey thus far had been a 40-gun six-master.

From pollywogs to shellbacks in such a short time, Kincaid thought. I’m proud of you people.

Robert Kincaid shook his head as the series of strange terms came to mind. He had no idea where they originated, just their context as they referred to a time long ago and on a far-distant planet called Earth. He often wondered what life was like back then, in the days of real seafaring pirates, when all a man had was the deck beneath his feet and the wind in his sails? He’d read it was glorious.

Many of the terms and traditions from those ancient nautical times were still in use. Sure, the sails they now unfurled were space-bending neutron projectors, and the winds they chased were ribbons of dark matter that guided the creation of the unpredictable and often dangerous stellar warp-currents they sought to catch. Still, the experience had to be the same. And now, like then, the price of failure was death.

Captain Robert Kincaid—formerly of the United Peoples of Earth, 9th Tactical Assault Group—was a seasoned veteran of space warfare and experienced enough to know the reality they faced. It was simple: They would either live today, or they would die. There was no in between. And yet there was still hope, a way for Robert to cheat destiny’s deadly stare.

All he had to do was reach the Drift Current in time.

Take a few hundred trillion tons of the rich soup of the interstellar medium, lace it with a jumble of strands of invisible dark matter the size of a planetary system, and then stretch it over three parsecs of space. What you’d end up with is a region of space called the Drift Current, an almost invisible, nebula-like pool of gravitational spider-silk, strings, ropes and cables. The masts of interstellar starships, with their neutron projectors and electromagnetic accumulators, are but teacups in the roaring maelstrom of swirling, stellar stew. Navigationally, the Current is a hazard for even the most-seasoned helmsman, and its expanding boundaries are carefully marked on star charts as close to actuality as possible in light of the ever-changing conditions.

Captain Kincaid had witnessed what happened to ships caught in the Current. The closest analogy was watching a vessel dashed to pieces on a coral reef. The trick for him would be to lure the Vixx’r into the Current without diving Malicious into the morass as well. It wouldn’t be easy. Not one bit.

“They’re still closing, sir. Weapons range in five minutes.”

“Very good, Mister Sinclair, steady as she goes.”

Robert pressed a button on the armrest of his command chair. “Attention crew of the Malicious. Target will be in range in five minutes, and even though she may outgun us two to one, it’s a pretty good bet she won’t be expecting what we can bring to bear, so we’ll have the element of surprise on our side. Cannon crew: Wait until we’ve made the turn before locking on target. Once we change course, we’ll only have one chance to deliver a salvo, so make it good. And there’s going to be some rough seas for a few minutes after we drop anchor, so factor that in before committing. Anchor crew: Stand ready to drop on my command. Everything must go smoothly; that’s an imperative. Four minutes everyone. Stay frosty. This is where the fun begins. Captain out.”

Robert turned to Javon Steele. “Get down to forward steering and make sure the anchor crew gets it right. We can’t afford to be off by even a degree.”

“Roger that. I’m on my way.” Steele ran from the bridge. It would take him forty seconds to reach the small compartment five decks below the bridge where a nervous anchor crew waited.

“Picking up current anomalies, Captain,” the helmsman reported. “I’m having to fight her quite a bit.”

“That’s the idea, Mister Devlin. Keep us in the channel the best you can, and get ready for a course change to zero-one-five, up twenty. Execute with anchor drop. On my order, not before.”

“Aye, sir.”

Robert looked out through the forward viewport just as the stars began to change color, shifting more to the blue, while their single points of light began to stretch out. They were entering the edge of the Drift Current, and if the anchor wasn’t set precisely, they would be sucked all the way in, with deadly consequences.

“Blast detected from the Vixxie ship, Captain!” Sinclair reported. “Tracking on target, contact in fifteen seconds.”

“Crap,” Robert said. This is going to be close.

“Captain?” the helmsman cried out.

“I know. Five more seconds.”

When Robert saw the surrounding starlight suddenly streak to port he pressed the intercom button. “Anchors away; prepare for heavy rolls! Helm, execute course change!”

The ship suddenly shifted to starboard, sending the bridge crew surging against their restraints, inertial compensators pressed to the max. The rest of the crew should have been similarly strapped in by now—and if not, there were going be some serious injuries. The Malicious swung by on a course now one-hundred-eight degrees out from her original heading. The stars in the viewport became nothing more than streaks of white and blue lines across the field of view.

Kincaid had a small tac monitor attached to his command chair and on it he could see a graphic representation of the Malicious as she followed an arcing course to starboard—just as the monstrous alien warship shot past them to port. Flashes of cannon fire erupted from the Vixx’r ship’s weapons deck, and for a moment his blood froze in his veins. He watched with relief as the plasma shells from the enemy vessel folded in upon themselves—an effect of the Current—revealing the alien’s inexperience with this region of space.

“Cut the anchor!” Kincaid commanded. Commander Steele was a split second ahead of him, as the Malicious broke free from her radically-arcing course and shot away from the Drift Current at a ninety-degree angle.

“Fire!” Kincaid shouted.

From their new vantage point behind the Vixx’r dreadnaught, multiple clear targeting sights were presented to his hungry aft gun crews. Unlike the Vixx’r, his gunners were quite familiar with the odd effects the Current would play on their shots and had already compensated for them. Now Robert watched as the Vixx’r ship was bathed in small puff-balls of fire and light, a result of his crew’s dead-on accuracy.

“Fire at will!” Kincaid yelled into the intercom, simultaneously—it turned out—with the first jolt of the ship as the main port cannon unleashed a deadly salvo of fire.

Apart from the hellish onslaught from the guns of the Malicious, the unfathomable clash between regular and dark matter in this region of space also wrought its own brand of havoc upon the warp-sails of the alien starship. She lost all control and began to drift helplessly to starboard, drawn in by the invisible hand of the Current.

Even more holes were blasted into her superstructure just below the main deck from the accurate aim of his gunners; however, Kincaid watched with interest as one of their plasma shells missed the side of the alien ship altogether. To his delight, the treacherous Drift Current plucked up the errant shot, and by a strand of dark matter, swept it back toward the aft mast, shearing it off completely. The giant, billowing sail broke apart and began to flutter off into space, appearing to be under the influence of some hidden breeze.

“Sighting on target, sir; we’re really giving it to them now!” Sinclair turned in his seat.

Kincaid’s smile—this time—was genuine. “Let me know when they can no longer return fire, Mr. Sinclair. I think I might want a souvenir from this battle.”

“Aye, Captain.” His weapon’s officer swiveled back to his panel. “Readings indicate…plasma ignition onboard.” At that moment a brilliant sunburst lit up the bridge through the forward viewport. Hands lifted to cover sensitive eyes, even as the monitors polarized to block out the damaging light.

“Damn…is she gone?”

“No sir; that was her magazine. She’s…sir…she’s dead in the water.”

“Cease fire!” Kincaid shouted, and watched as the salvos from his ship halved in number.

“Cease fire, dammit!”

Finally the deadly eruptions dropped to zero. Their blood is up, he thought.

Years of Vixx’r occupation has made a simple command not nearly enough. By God, they hate them as much as I do.

“Open a ship-wide channel, Mister Sinclair. I want to hear what’s going on below decks.”

The sound of cheering washed across the bridge.

“Well done, people,” Robert said.

“We did it, Cap’n!” an ecstatic voice called out, and he wondered who it was? He couldn’t help but smile.

“You sure did, and you all deserve medals, if pirates gave out medals. Now secure from General Quarters. Set condition yellow. Damage control crews stow all gear. Gunners take inventory and then secure all armament.”

Steele arrived back on the bridge a few minutes later, a big grin on his chocolate brown face. “I see now how spending your misplaced youth wandering around this part of space finally came in handy. Great job Captain.”

“Same to you, Mister Steele.”

“I guess we can learn something from this little mishap, like make sure we know what we’re up against before committing to an engagement.”

“What, and take all the fun out of pirating? No way! But our job here isn’t done, not yet.”

Steele frowned. “What do you mean?”

“That,” Kincaid pointed at the viewscreen. The Vixx’r ship still struggled on the edge of the Drift Current, appearing as though she might break free at any moment. Somewhere aboard the dying ship, there was a Vixxie at his post, working earnestly to get the ship to clear space.

“What about it?” Steele said. “Done deal.”

“If we leave them they’ll eventually make their way out of the Current. We have to go mop up the mess we’ve made. And for our trouble, I think a six-master should be a fair trade.”

“Make that a five-master now, Captain…for what good it will do. We barely have enough crew for the Malicious.”

Kincaid frowned and pursed his lips. “That is a problem; a fancy new starship and with no one to drive her.”

“She’s not so new, not anymore.” Steele now mirrored Robert’s furrowed forehead. “You know every time you make a pitch for new recruits you run the risk of being found out. And then what would we do if the Vixxie have you for dinner?”

“Hopefully I’d give them indigestion.”

“Robert—”

Kincaid raised his hand. “I know, Javon, and thanks for your concern, but we both know the time will come eventually.”

Steele grimaced. “I’m your friend and shipmate, but that thing there—the dreadnaught—could be a lot more serious than the revelation that you’re the infamous Captain Malicious. It could have some very dire consequences for the rest of the Human population in the Reaches.”

Kincaid nodded. “Rest assured, Commander, plans have been made to prevent that from happening. We just have to trust the UPE when that time comes.”

Steele’s frown turned into a sour smirk. “Trust the government to do the right thing, like defend the Reaches against the Sludgers? We all know how that turned out.”

“That was different, Javon, and you know it.” And then he smiled. “Besides, all they have to do in this case is betray one person—me! I’m sure even the government of the UPE can’t screw that up!”

It was a young graduate student in the mid-21st century named Holland Norvell who first came up with the formula for faster-than-light travel.

While working on his doctoral thesis in quantum mechanics, Norvell kept hitting the brick wall of a mysterious thing called “gravity,” something that had never been previously well-defined. From not long after the time of Sir Isaac Newton, gravity had been labeled as “the weakest of the nuclear forces,” the implication being that gravity had something to do with the atom and with the laws of cohesion and adhesion. But nothing seemed to fit the model of the universe the young, eccentric genius envisioned—that of mankind traveling throughout the stars in real-time and not over centuries as was the present level of technology.

As the historians record, in the wee hours of the morning, a week before his thesis defense, Norvell picked up his yogurt spoon and dropped it. He picked it up again, and once more let it fall to the table. Again and again he repeated the process. Lift the spoon. Drop the spoon.

It’s then believed he asked the empty room, “What am I looking at?”

His own voice answered: “Gravity.”

Norvell’s mind must have then gone off into a fugue state or a black hole or something—the other side of the universe perhaps—because he was soon asking aloud, “But what would it be like if I dropped the spoon on the surface of something other than a gigantic electromagnet spinning in space?”

It dawned on him that no one in recorded history had ever asked that question, and as the mythology goes, Norvell then opened his computer and erased the title of his thesis, and replaced it with large block letters that read:

GRAVITY IS DEAD.

He then began to reconstruct the universe based upon the supposition that there was no such thing as gravity, that there was only electromagnetism.

The day of Norvell’s thesis defense came and went, and nobody saw him and he wouldn’t answer his pad. He emerged from his room three weeks later, much thinner, yet with the answer to his question. Within that time he had figured out how galaxies adhere and why they pool into squashed spirals. It was so obvious to him now. So-called gravity was instantaneous.

Einstein must have turned over in his grave so fast that he blurred to invisibility.

From Norvell’s early theories came many more, including the equation that permitted travel to the stars.

In the Captain’s lounge aboard the Malicious, Steele raised a glass of rare specialty port and toasted, “To Norvell!”

“To Norvell!” Kincaid replied. After draining the glass of its potent contents, Robert got down to business. “As soon as we get the tow lines secured, let’s make best speed back to base. Then we’ll take my flitter back to Ione. We should be home by late afternoon the day after tomorrow.” “So you’re still going through with it?” Steele asked.

“I don’t have a choice. You said it yourself: we barely have enough crew for the Malicious. I need bodies, and I need them now. And after that, there’s a meeting scheduled at KST that I don’t want to miss. Gaolic’s going to be there, I believe.”

“You need to be careful, Robert. That old Vixxie is a patient son-of-a-bitch, while you’re the most impatient man I know. That’s not a good combination. Also, I wouldn’t expect much out of your friends at the Duck. It takes a special breed of fool to do what we do.”

Kincaid smiled. “I hear that. But I’ve only invited the ones I believe have what it takes.”

“What’s that—a terminal illness and with nothing left to lose?”

“You are one sour cynic, aren’t you, Commander? I’m expecting you to make the meeting. I’m going to need your back-up.”

“I’ll be there. In fact I think it might be quite entertaining watching you explain our mission to a bunch of landlubbers.” Steele them lifted his glass and observed the dark burgundy color through the light. “Good stuff this port of yours. Beats the hell out of the swill they’re brewing in the Reaches these days.”

“The recipe’s been in my family for hundreds of years. A distant branch of the family still owns a winery back on Earth—or so I’ve been told. I’ve never been there myself.”

“You could go, you know?”

“To Earth?” Kincaid shook his head. “No way, I have to stay here and nursemaid this glorious revolution we have going against the Vixx’r Occupation of the Reaches.”

“I don’t know that it’s technically a revolution yet, not until….”

“Until what?”

“Until the people rise up. That’s why they call it…an uprising. It seems to me everyone is settling down for the long run, everyone except us.”

“That’s why I can’t go to Earth. Someone needs to light a fire under them. Too many are accepting the current situation as a permanent state of affairs.”

Javon Steele nodded.

At that moment Sinclair’s voice intruded over the comm. “Captain, tow lines are secure. We’ve got the ship.”

“Very good, Mister Sinclair. Captain out.”

“I still say you should cancel the meeting at the Duck,” Steele said. “We can find recruits in a less public way, more one-on-one.”

“I have to go, Javon. Besides, I know all these people; have my whole life. I’ll be fine.” Robert Kincaid was tired, and he wore his exhaustion on his face and in his every movement. He set the empty glass on the coffee table. “Give the word Mister Steele: Best speed back to base. Our destiny awaits.”

0 notes

Text

A stab at an Authors' Note for 1889: Journey to the Moon

A stab at an Authors' Note for 1889: Journey to the Moon (note: Facebook omits the italics when you paste text in. Simply imagine dozens of emphasis-laying italicized words in the following sermon--can you say "Amen-nah!"? I knew you could):

What is Steampunk?

To answer the question, it’s almost simpler to state what steampunk is not. When fans attempt to explain the concept of steampunk to an inquiring friend, to bridge the communication gap the fan will in the end invariably resort to, “Did you ever see The Wild Wild West?” It’s sort of a putdown of the genre to have to ask this question. No, there’s nothing wrong with The Wild Wild West. It’s just that there is a dearth of possible comparables in modern literature. Or, it’s difficult to remember one. There are actually many books, films, and even popular video games that are on the fringe of the steampunk movment—and let me assure you, steampunk is a movement. The movie version of The Wild Wild West starring Will Smith is far closer to modern steampunk than the old TV serial. But there’s something to be said for the serial. For many of us older writers, back in the day we ate it up.

But what is steampunk not? Well, steampunk is not science fiction, even though you will find steampunk in the science fiction section of your bookstore (the problem is that you are likely to find it only in the sci-fi section, but more on that in a moment). Oh yes, steampunk has some of the elements of science fiction, but it’s like saying that your local Renaissance Fair is a “fantasy theme park.” (Note: don’t tell the armorer who forges the platemail breastplates for the renaissance fair that he is engaging in “fantasy”. He—or in some instances, she—is liable to punch your lights out). If you then chunked in the Civil War and Revolutionary War re-enactors into the fantasy category, you would be even closer to what is wrong with the “steampunk is science fiction” error. So, it’s not science fiction. It’s not fantasy (see above). It’s not, strictly, revisionist history. And it’s not even horror, despite the horror element of throwing in the occasional zombie, werewolf, vampire, etc., into the steampunk mix. No. We are talking about steampunk itself. Any steampunk book may have elements of science fiction, fantasy, horror, revisionist history, gothic, antediluvian technology, time travel, or any one of a hundred other genres of fiction. But it is not those genres, strictly speaking.

Knowing what steampunk is not assists us to define what it is. The answer, of course, is a simple one. Steampunk is fiction. It is its own genre of fiction, and should be treated as such, despite its current placement of bookstore shelves. I believe that book distributors (the companies that actually set policy with regard to bookstore shelves—and believe me, they pay to have the shelves aligned and divided the way they are) and bookstore managers have no faintest idea what steampunk is. So, when you have the opportunity to correct this error, please, for us and for yourself, please set them straight. What we’re suggesting is that get the bookstore manager’s attention, lead them over to the bookstore shelf (that’s right, the science fiction section) where Cherie Preist’s The Clockwork Century books are nestled in next to Terry Pratchett’s Discworld cycle, inform them that this arrangement will not do, and kindly suggest a sparate section for all of the steampunk books they have in stock. If you are brave enough to carry this through, you are likely to be met with a long silence. In this vast silence, you can begin by pulling Ms. Priest’s books off the self and lay them in a stack, then go down the line of shelves pulling half a hundred steampunk titles and drop them onto the same stack. But once you’re done, don’t be alarmed to discover something new. It’s a new thought, really—each of these books, in some measure, is science fiction. Also, they are horror. They are revisionist history, and they are fantasy and half a hundred other sub-genres. Oh boy. It gives one chills. But that’s not the point. They are, each one, also something...else. That something else is steampunk. Be proud. You have arrived as a member of the most subtle invasion force this planet has ever witnessed. You are a steampunker.

Steampunk is not purely Victorian Era fiction. It’s not purely tales of never-before invented steam machines. It’s not purely revisionist history. It’s not pure anything. But what is is, largely, the people who attend steampunk conventions and dress up in 19th Centurty clothing (and clothing that you’ve never seen before) and who read the books and post in online forums know instinctively as steampunk.

So, there you have it.

We hope you have enjoyed 1889: Journey to the Moon. Its sequel, in what we’re calling The Far Journey Chronicles, is 1899: Journey to Mars. That book should be here where you found this volume in the coming months—or, who knows, maybe it will have its own section by then! There will be more after that, we assure you.

In the meantime, please continue reading the many other estimable steampunk authors out there. Please continue interacting with us—all of us—in the online forums, by email, on Facebook and Twitter and however and wherever you can. And please, keep steampunking along.

Bye for now, and all the best to you and yours.

Billy Kring

Sabinal, Texas

George Wier

Austin, Texas

0 notes

Video

youtube

How to Publish Your Book, Novel, or Short Story, Self Publishing vs. Traditional Publishers

0 notes

Text

About 1889

I'm back in a time that never was--it's 1889, and eleven people are on a strange steam-powered spaceship to the Moon. Included in the crew are such unlikely passengers and crew as: Billy The Kid, Nikola Tesla, Jack The Ripper, a Sioux warrior out for the blood of George Armstrong Custer (who did not die at the Little Bighorn), a Cossack warrior-princess, a battery of robots, a half-man and half-cyborg engineer, a Punjabi mathematician and linguist, a big-game hunter from Africa, and the grandson of Blackbeard the Pirate, not to mention the genius who designed the ship. There are aliens on the Moon with evil intentions, the robots are wound a little too tightly, and no one knows that the Ripper is along for the ride except for the Londoner himself. What could possibly go wrong? At 30,000 words at the moment on 1889: Journey To The Moon. God Bless Billy Kring, my amazing co-author!

0 notes

Photo

This is Billy Kring (right) and I. We are co-authoring 1889: Journey To The Moon!

0 notes