Text

In: Dust of Dreams, Malazan the book of the fallen

After a long moment, Brys returned his attention to the canal waters below. ‘This all flows out to the river, and the river into the sea, and out in the sea, the silts collected back here end up raining down to the bottom, down on to the valleys and plains that know no light. Sometimes,’ he added, ‘souls take the same journey, and they rain down, silent, blind. Lost.’ ‘You two keep this up,’ Cuttle said in a growl, ‘and I’ll do the jumping.’ Fiddler snorted. ‘Sapper, listen to me. It’s easy to listen and even easier to hear wrongly, so pay attention. I’m no wise man, but in my life I’ve learned that knowing something—seeing it clearly— offers no real excuse for giving up on it. And when you put what you see into words, give ’em to somebody else, that ain’t no invitation neither. Being optimistic’s worthless if it means ignoring the suffering of this world. Worse than worthless. It’s bloody evil. And being pessimistic, well, that’s just the first step on the path, and it’s a path that might take you down Hood’s road, or it takes you to a place where you can settle into doing what you can, hold fast in your fight against that suffering. And that’s an honest place, Cuttle.’ ‘It’s the place, Fiddler,’ said Brys, ‘where heroes are found.’ But the sergeant shook his head. ‘That don’t matter one way or the other. It might end up being as dark as the deepest valley at the bottom of your ocean, Commander Beddict. You do what you do, because seeing true doesn’t always arrive in a burst of light. Sometimes what you see is black as a pit, and it just fools you into thinking that you’re blind. You’re not. You’re the opposite of blind.’ And he stopped then, as he saw that he’d made both hands into fists, the knuckles pale blooms in the gathering night. Brys Beddict stirred. ‘I will see the crews sent out to the imperial well tonight, and I will roust my healers at once.’ He paused, and then added, ‘Sergeant Fiddler. Thank you.’ But Fiddler could find nothing to be thanked for. Not in his memories, not in the words he had spoken to these two men. When Brys had left, he swung round to Cuttle. ‘There you have it, soldier. Now maybe you’ll stop worshipping the Hood-damned ground I walk on.’ And then he marched off. Cuttle stared after him, and then, with a faint shake of his head, followed his sergeant.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“[...] o destino das coisas que dizemos e fazemos está nas mãos de quem as usar depois. Comprar uma máquina sem questionar ou acreditar num fato sem duvidar tem a mesma consequência: fortalece a situação do que está sendo comprado ou acreditado, robustece-o como caixa-preta. Desacreditar ou, digamos, ‘descomprar’ uma máquina ou um fato é enfraquecer sua situação, interromper sua disseminação, transformá-lo em beco sem saída, reabrir a caixa-preta, seccioná-la e recolocar seus componentes em outro lugar. Deixados à própria mercê, uma afirmação, uma máquina, um processo se perdem. Atentando a penas para eles, para suas propriedades internas, ninguém consegue decidir se são verdadeiros ou falsos, eficientes ou ineficientes, caros ou baratos, fortes ou fracos. Essas características s´são adquiridas pela incorporação em outras afirmações, outros processos e outras máquinas. Essas incorporações são decididas por nós, individualmente, o tempo todo. Confrontados com uma caixa-preta, tomamos uma série de decisões. Pegamos? Rejeitamos? Reabrimos? Largamos-nos dela sem discutir? Ou vamos transformá-la de tal modo que deixará de ser reconhecível? É isso o que acontece com as afirmações dos outros em nossas mãos, e com as nossas afirmações nas mãos dos outros. Em suma, a construção de fatos e máquinas é um processo coletivo. (Essa é a afirmação na qual espero que você acredite; o destino dela está em suas mãos tanto como o destino de outras afirmações.) Isso é tão essencial para a continuação de nossa viagem pela tecnociência que será chamado nosso primeiro princípio: o restante desse livro justificará essa pomposa denominação.

Latour, Bruno. Ciência em Ação. Como seguir cientistas e engenheiros sociedade afora. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 1998. p. 43

0 notes

Photo

Sobre a alienação do trabalho sob o capitalismo.

Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (Moscow: Progress, 1959), p. 69.

0 notes

Text

Marx, acumulação primitiva e a crítica à justificativa das elites morais

This primitive accumulation plays in Political Economy about the same part as original sin in theology. Adam bit the apple, and thereupon sin fell on the human race. Its origin is supposed to be explained when it is told as an anecdote of the past. In times long gone by there were two sorts of people; one, the diligent, intelligent, and above all, frugal elite; the other, lazy rascals, spending their substance, and more, in riotous living . . . . Thus it came to pass that the former sort accumulated wealth, and the latter sort had nothing to sell except their own skins. And from this original sin dates the poverty of the great majority that, despite all its labour, has up to now nothing to sell but itself, and the wealth of the few that increases constantly although they have long ceased to work. Such insipid childishness is every day preached to us in the defence of property . . . . As soon as the question of property crops up, it becomes a sacred duty to proclaim the intellectual food of the infant as the one thing fi t for all stages of development. In actual history it is notorious that conquest, enslavement, robbery, murder, briefly force, play the part . . . . The methods of primitive accumulation are anything but idyllic.

Karl Marx, Capital, 3 vols. (Moscow: Foreign Languages, 1961), vol 1, p. 713-714

0 notes

Text

Marx e a opressão sistêmica do capitalismo para aumentar as horas de trabalho

In its blind unrestrainable passion, its were-wolf hunger for surplus-labour, capital oversteps not only the moral, but even the merely physical maximum bounds of the working-day. It usurps the time for growth, development, and healthy maintenance of the body. It steals the time required for the consumption of fresh air and sunlight. It haggles over a meal-time, incorporating it where possible with the process of production itself, so that food is given to the labourer as to a mere means of production, as coal is supplied to the boiler, grease and oil to the machinery. It reduces the sound sleep needed for the restoration, reparation, refreshment of the bodily powers to just so many hours of torpor as the revival of an organism, absolutely exhausted, renders essential. It is not the normal maintenance of the labour-power which is to determine the limits of the working day; it is the greatest possible daily expenditure of labour-power, no matter how diseased, compulsory, and painful it may be . . . . Capital cares nothing for the length of life of labour-power. All that concerns it is simply and solely the maximum of labour-power, that can be rendered fluent in a working-day. It attains this end by shortening the extent of the labourer's life, as a greedy farmer snatches increased produce from the soil by robbing it of its fertility.

Karl Marx, Capital, 3 vols. (Moscow: Foreign Languages, 1961), vol 1, p. 264-65

0 notes

Text

Marx, a origem do mais-valor na produção e a crítica aos autores que a procuravam na esfera da circulação

“We therefore take leave for a time of this noisy sphere [of circulation], where everything takes place on the surface and in view of all men, and . . . [go] into the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there stares us in the face "No admittance except on business." Here we shall see not only how capital produces, but how capital is produced. We shall at last force the secret of profit making. This sphere that we are deserting . . . is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. There alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because both buyer and seller of a commodity . . . are constrained only by their own free will. They contract as free agents . . . . Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together, and puts them in relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and private interest of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself above the rest, and just because they do so, do they all, in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all-shrewd providence, work together to their mutual advantage, for the common weal and in the interest of all. On leaving this sphere of simple circulation or of exchange of commodities, which furnishes the "Free-trader Vulgaris" with his views and ideas, and with the standard by which he judges a society based on capital and wages, we think we can perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as the capitalist; the possessor of labourpower follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but a hiding.″

Karl Marx, Capital, 3 vols. (Moscow: Foreign Languages, 1961), vol 1, p. 172

0 notes

Photo

the quest for ever greater quantities of surplus value as the motive force propelling the entire capitalist system

Hunt and Lautzenheiser, 2011, History of Economic Thought: a critical perspective, p. 213

0 notes

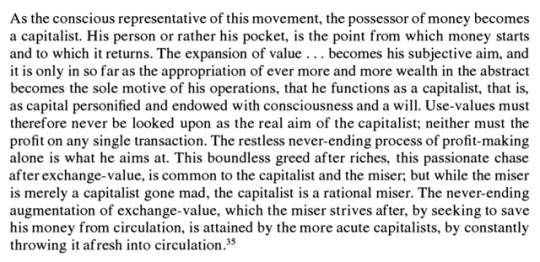

Photo

Hunt and Lautzenheiser, 2011, History of Economic Thought: a critical perspective, p. 81

0 notes

Text

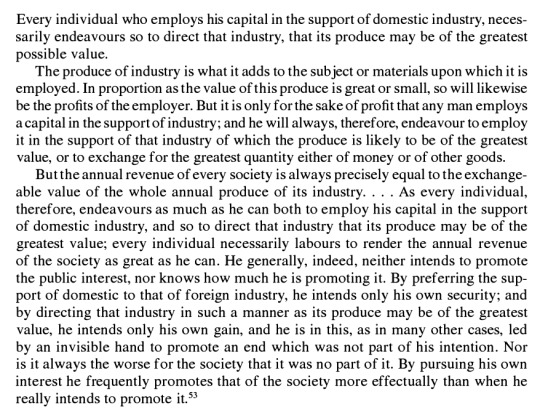

A famosa passagem com menção à “mão invisível” em Adam Smith

Adam Smith. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. (New York: Modern Library, 1937), p. 422-423. (apud Hunt and Lautzenheiser, 2011, History of Economic Thought: a critical perspective, p. 48-49).

0 notes

Quote

It is not, however, difficult to foresee which of the two parties must, upon all ordinary occasions, have the advantage in the dispute and force the other into a compliance with their terms. The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily; and the law, besides, authorizes, or at least does not prohibit their combinations, while it prohibits those of workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work; but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes the masters can hold out much longer. A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, or merchants, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. . . . Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour. . . . We seldom, indeed, hear of this combination, because it is the usual, and one may say, the natural state of things which nobody ever hears of. Masters too sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate. These are always conducted with the utmost silence and secrecy, till the moment of execution, and when the workmen yield, as they sometimes do, without resistance, though severely felt by them, they are never heard of by other people. Such combinations, however, are frequently resisted by a contrary defensive combination of the workmen. . . . But . . . their combinations . . . are always abundantly heard of. . . . They are desperate, and act with the folly and extravagance of desperate men, who must either starve, or frighten their masters into immediate compliance with their demands. The masters upon these occasions are just as clamorous upon the other side, and never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combinations of servants, labourers, and journeymen. The . . . [workers' ] combinations . . . generally end in nothing, but the punishment or ruin of the ring-leaders.

Adam Smith. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. pp. 66-67. (apud Hunt and Lautzenheiser, 2011, p. 48-49).

Adam Smith sabia claramente da assimetria entre capitalistas e trabalhadores na disputa entre lucros e salários.

0 notes

Photo

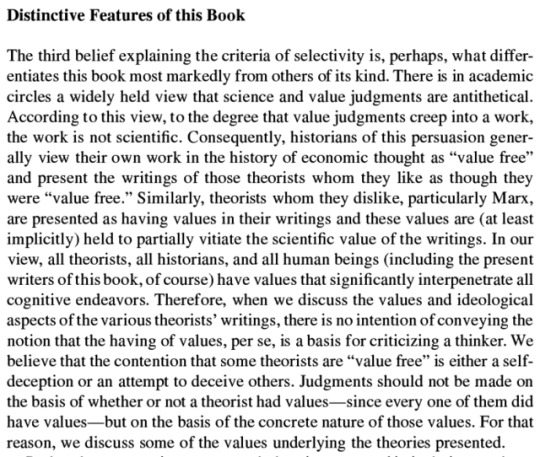

Hunt, E.K. & Lautzenheiser, M. 2011. History of Economic Thought - A critical perspective. Preface, p. xix

0 notes

Photo

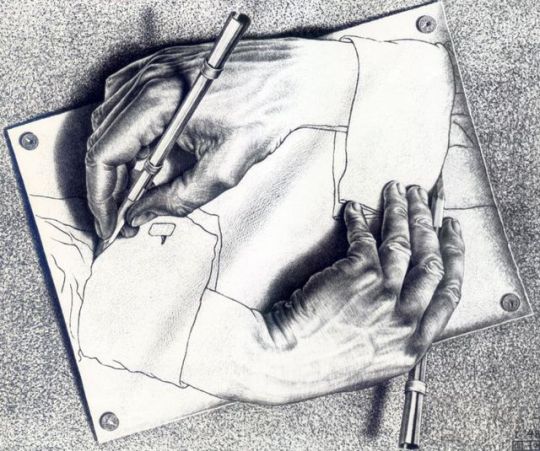

The politics of technology grows out of the technical mediations that underlie the many social groups that make up society. A worker in a factory, a nurse in a hospital, a truck driver in his truck—all are members of social groups that exist through the technologies they employ. Consumers and victims of the side effects of technology form latent groups that surface when they become aware of their shared experience. Encounters between individuals and the technologies that connect them proliferate with a myriad of consequences. Social identities and worlds emerge simultaneously and form the backbone of a modern society. In the terminology of science and technology studies, they “co-produce” each other.

Co-production has a paradoxical structure nicely illustrated by M. C. Escher’s famous print Drawing Hands. In his book Gödel, Escher, Bach Douglas Hofstadter described Escher’s self-drawing hands as a “strange loop” and an “entangled hierarchy.”8 These terms refer to an unusual type of logical relation in which top and bottom change places. Artist and drawing stand in a hierarchy, the active side at the top, the passive side at the bottom. In the print both hands play both roles; the hierarchy is entangled in a strange, endless loop.

[…]

Like these examples of strange loops, society and technology are inextricably imbricated. Social groups exist through the technologies that bind their members together. In this they resemble the drawn hand of Escher’s print. But once bound together the members gain a power over the technologies that bind them. They take the place of the hand that draws. Formed and conscious of their identity, technologically mediated groups influence technical design through their choices and protests. In so doing they reiterate the original paradox of democracy: self-rule is an entangled hierarchy. As the French revolutionary Saint-Just put it in 1791, “The people is a submissive monarch and a free subject.”

Feenberg, Andrew (2017). Technosystem: the Social Life of Reason. Harvard University Press, p. 9-10.

0 notes

Quote

In Engels's argument, and arguments like it, the justification for authority is no longer made by Plato's classic analogy, but rather directly with reference to technology itself. If the basic case is as compelling as Engels believed it to be, one would expect that, as a society adopted increasingly complicated technical systems as its material basis, the prospects for authoritarian ways of life would be greatly enhanced. Central control by knowledgeable people acting at the top of a rigid social hierarchy would seem increasingly prudent. In this respect, his stand in "On Authority" appears to be at variance with Karl Marx's position in Volume One of Capital. Marx tries to show that increasing mechanization will render obsolete the hierarchical division of labor and the relationships of subordination that, in his view, were necessary during the early stages of modern manufacturing. The "modern Industry", he writes, "... sweeps away by technical means the manufacturing division of labor, under which each man is bound hand and foot for life to a single detail operation. At the same time, the capitalistic form of that industry reproduces this same division of labour in a still more monstrous shape; in the factory proper, by converting the workman into a living appendage of the machine..." In Marx's view, the conditions that will eventually dissolve the capitalist division of labor and facilitate proletarian revolution are conditions latent in industrial technology itself. The differences between Marx's position in Capital and Engels's in his essay raise an important question for socialism: What, aftet all, does modern technology make possible or necessary in political life? The theoretical tension we see here mirrors many troubles in the practice of freedom and authority that have muddied the tracks of socialist revolution.

(pg. 130) Winner, L. Do artefacts have politics?. Daedalus, vol. 109, no. 1, Modern Technology: Problem or Opportunity? (Winter, 1980), pp. 121-136. Published by: The MIT Press on behalf of American Academy of Arts & Sciences https://www.jstor.org/stable/20024652;

0 notes

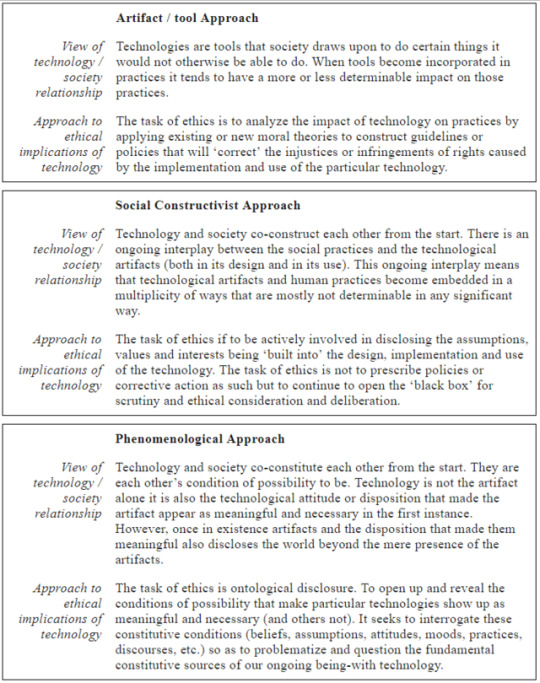

Photo

Introna, Lucas, “Phenomenological Approaches to Ethics and Information Technology”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/ethics-it-phenomenology/>.

0 notes

Quote

In thinking about our relationship with technology in modern contemporary life Albert Borgmann (1984) takes up the question of the possibility of a ‘free’ relation with modern technology in which everything is not already ‘framed’ (in Heidegger’s sense) as resources for our projects. He agrees with Heidegger’s analysis that modern technology is a phenomenon that tends to ‘frame’ our relation with things, and ultimately ourselves and others, in a one-dimensional manner—the world as simply available resources for our projects. He argues that modern technology frames the world for us as ‘devices’. By this he means that modern technology as devices hides the full referentiality (or contextuality) of the world—the worldhood of the world—upon which the devices depend for their ongoing functioning. Differently stated, they do not disclose the multiplicity of necessary conditions for them to be what they are. In fact, just the opposite, they try to hide the necessary effort for them to be available for use. A thermostat on the wall that we simply set at a comfortable temperature now replaces the process of chopping wood, building the fire and maintaining it. Our relationship with the environment is now reduced to, and disclosed to us as a control that we simply set to our liking. In this way devices ‘de-world’ our relationship with things by disconnecting us from the full actuality (or contextuality) of everyday life. By relieving us of the burden—of making and maintaining fires in our example—our relationship with the world becomes disclosed in a new way, as simply there, already available for us. Obviously, this is sometimes necessary otherwise the burden of everyday life might just be too much. Nevertheless, if the ‘device mood’ becomes the way in which we conduct ourselves towards the world then this will obviously have important moral and ethical implications for others who may then become disclosed as devices.

Against such a disengaging relationship with things in the world Borgmann argues for the importance of focal practices based on focal things. Focal things solicit our full and engaging presence. We can think of the focal practice of preparing and enjoying a meal with friends or family as opposed to a solitary consumption of a fast food meal. If we take Borgmann’s analysis seriously we might conclude that we, as contemporary humans surrounded by devices, are doomed increasingly to relate to the world in a disengaged manner. Such a totalizing conclusion would be inappropriate since the prevailing mood does not determine our relationship with those we encounter. Nevertheless, Borgmann’s analysis does point to the possibility of the emergence of a device mood—as we increasingly depend on devices—and our moral obligation not to settle mindlessly into the convenience that devices may offer us. Otherwise we might, as Heidegger (1977) argued, become the devices of our devices.

Introna, Lucas, "Phenomenological Approaches to Ethics and Information Technology", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/ethics-it-phenomenology/>.

0 notes

Photo

Wallerstein, I. (1996) Historical Capitalism - with Capitalist Civilization, Verso Books, NY. p. 69

0 notes