Text

“I thought I would be understood without words.”

—

17K notes

·

View notes

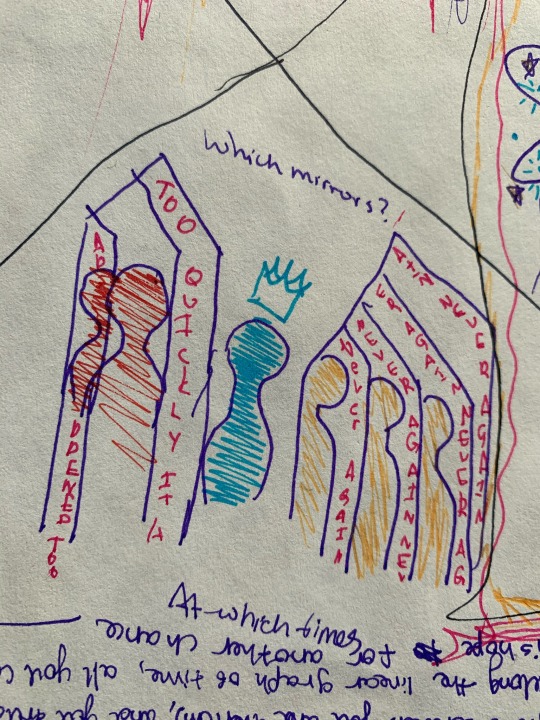

Photo

Hélène Cixous, Hyperdream (tr. Beverly Bie Brahic)

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

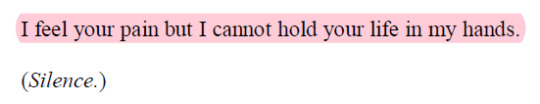

This particular quote in the Fagles translation of the Oresteia hits a little too close to home.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You—all, all real. I—all delusion.”

— — Paul Celan, from “[(I know you],” Breathturn into Timestead, tr. Pierre Joris

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Iam the root and the opposite of myself only lmao

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Муж мій, це ти лежиш тут?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Owl

Shrouded by the night in her living room, digested by the walls of a purple bean bag, Aziza filled her cheeks with cheap salty snacks and enjoyed the panorama of the building in front of her window. In her unseasoned hand she held opera glasses, the manicured pointer of which she draped along the polished handle with the utmost poise. This contrasted the shoveling her other hand did from a crinkling chip bag to her wet mouth.

She had decided the only way she would get acclimated to these sessions was if they felt like grand occasions. In her mind she was truly able to believe she was a noblewoman with an interest in the avant-garde, bored of the humdrum theater and its choreographed, raucous applause, thus forced to find new entertainment. Really, she was a stranger peering through her neighbor’s windows.

She wore a burgundy velvet wrap dress that she had stolen from her sister because she was enticed by the way it had enough room for one thigh to surface coyly from the flowing fabric. Her leg, which grazed the yellow light from the quarters across her window, looked sickly in the hue of the living. She laid the binoculars on her lap and delicately crossed her legs to cover it up. She wiped crumbs off of her breasts and stomach and retrieved those weighty glasses again. The handle was a dark, polished wood finished with geometric loops and patterns a similar color to her dress. She scratched away at the wax with her thumb while she gazed, and this one nervous comfort was making grooves into the wood. If she squeezed hard enough, for long enough, she could leave that same pattern in her hand for a few minutes, an aggravated red. She would be red on the outside and the inside. In this fashion, white-knuckled, she enjoyed the show.

From the beanbag the red heap could look outside without being seen. She would never be blind again, that was the resolve of the night. She would not be Patricia K., who was currently pacing quite conveniently from one end of her window to the other, listening intently and with bloodshot eyes to the phone. She would not be James R., just a few windows to the right, who was drinking in his underwear and staring through the television. She was not the young couple, only half visible on the 6th floor, that had been steadily flirting for about an hour, and who had undressed slowly as Aziza did continuous double takes in their direction. After they had writhed into bed they turned their light, and their show for the girl in red, off. She had, of course, been that naive a short time ago, back when she was unaware that the eyes of New York City never closed to dream, and might always be gazing in her direction.

Her mother, an infamous psychoanalyst who specialized in abnormal sexual disorders and persuasions, counseled Aziza when she found her daughter’s knees trapped in the bars of a staircase in the family home, where she had been watching her family watch a Christmas program.

“Which of the emotions that you felt when he was stalking you now inspire you to watch others?” Her mother always spoke like she was leading a guided meditation, and chose her words very carefully. Sometimes she waved her wrinkled walnut hands in slow, fluid movements over Aziza’s eyes. If they were doing hypnosis and she was really getting into it, her chin would tilt ever so towards the ceiling, her eyes half closed. At that angle the fat gathering under her chin would stretch and seem to expand, like a frog leaning back to croak and enjoy the sun. Aziza looked at her mother’s chin(s) instead of sharing in that ecstasy.

“If we know what you’re thinking about when you’re upset we can tidy up your mind, and then you won’t have to watch others.” Her mother would always say, carefully replacing ‘stalk’ with ‘watch’. Aziza imagined pulling a fishing net from the waters of her thoughts and sorting through the unearthed garbage. Somehow, it wasn’t that easy, but she gave it a try once in a while and scribbled down the ugly things she found within her on the back of a wrinkled post office receipt. The list so far was bored, useless, confused, overwhelmed, and underwhelmed.

Distraught. While she licked her fingertips clean and her stomach swirled through the floor, leaving her prone on the beanbag, she decided to add distraught to the list. With fingers slicked by saliva and oil, she jotted it down on that same receipt and tossed the pen away.

She could choose not to be distraught so long as she had a view of life on the outside of her decked out body. The silence of her living room was a respite from herself, and she filled that vacuum with the lives of others. She learned to hold onto the view until her anguish diminished enough for her to trace her feelings back to their traumatic origins. To do so, she focused her eyeglasses on one apartment like the wide eyed, fixed stare of an owl. She tugged on the rope of her ‘fishing net’, it tightened around a body, and she became him.

She was a gentleman against the daunting hum of a refrigerator, propped open and beaming so bright the night crushed the room surrounding. All that was visible against the black gathering in the hole of the apartment was her and all the food. She, in her boxers with an itchy groin, looked like an angel consulting a coffin, if only she were at the right angle to see it. From within this holy closet she pulled out a yogurt, closed the fridge, and let the night take everything else. A shame that she couldn’t appreciate herself in this candid way. In those moments, she was beautiful the way a child was beautiful, so genuine and unaware of their effect on others that one can’t help but fall in love.

That should be...apartment 7B. Oh, Harold. She knew Harold. He was responsible for repairing a lot of the elevator issues in the neighborhood. His tank tops were always stained yellow at the armpits, and every white shirt he had was tinged with some kind of blue-grey grime. He looked her in the eyes too long when they exchanged good mornings. His car had a bumper sticker that read, “Elevator men always get it up.”

Now that he was out of sight, being him felt pathetic. She did not need this, and it crumbled into the bean bag folds of her brain, not forgotten but filed away like everything else she knew about him. This way, being him could feel simple, stress-free. She was distraught because she could not be careless in the middle of the night, unbathed and warm with deep sleep. She did not use dairy at midnight to lull herself back to the crib. But Harold did, and would never know she was witness to his ignorance and bliss. Aziza mourned that she could never let herself be those two things, ignorant and blissful, at the same time ever again. She hand-picked these dreamy feelings, stolen from her guileless neighbor, and hung them among the heavy velvet that laid limp over her form, right over her heart—a shield. She let her head fall back off the bean bag and the vertebrae along her spine popped in order like dominos. Then she rose again, like air.

Stealing feelings like this could carry Aziza away on the winds of fantasy for a long time, maybe even until the next time the sun set. She would recreate her neighbor’s innocence during the day, walk the easy walk of the unsuspecting to work. At work, she could smile the easy smile of a trusting person, and she could respond as if she wasn’t dying to know what people were thinking about in that chasm they call their brains. Anything, anything, could be simmering beneath a smile and easy, cotton-candy sweet expressions. Aziza knew because she practiced hiding her own simmerings, and the more she practiced the more anxious she was that someone just as skilled would see her for who she was. She dreaded social pressure as if that type of heat could melt away her sugary facade like a warm, wet tongue.

No, not that, not ever again. Now she was the one who looked and melted other people’s fake and slippery natures. And she worked the best job in the world—she was a journalist for her local newspaper, and had her own column especially dedicated to interviewing the veterans of war. She was being paid to peer, scrutinize, and interpret other people’s lives. What a dream come true.

At home, so loved they never collected dust, she kept tapes of her interviews in boxes. Tapes that couldn’t be shown to her boss. She would zoom in on hairy moles pricked with hair, or a trembling, spastic hand trying to hold a cigarette steady, or staling piles of white gunk gathering in the corners of the lips of harrowed men. She took in each detail as if she alone understood, completely and truly, what all of these little signifiers meant. She absorbed worlds of emotion and meaning from her interview subjects, and what they were actually saying to her didn’t seem to matter as much.

She sometimes felt like her former stalker had destroyed who she was completely, but in doing so opened her up to a view of humanity only God could hold. Every time her perceptive eye snatched up another stray signal from people’s candid expressions, things they meant to hide or didn’t realize they were doing, it was like she could finally hold onto life and unveil its disguises. And underneath that, she felt, the whole world was made out of the same stuff.

She was haunted by the same vision every night. She was sitting at her kitchen table, with a laptop resting over a yellowing tablecloth. There was a black hole with a rusty brown rim singed into the cloth right by her typing hands. Without knowing why, she stopped and looked up. The dark room around her was invisible because the blue light in her screen was piercingly bright. On a wave of wind, ushered towards her seated body from some unknown location, some window unseen, are the voices of every interview subject she’s ever spoken to. The voices of men and women, grisly or bright, haunted or heart-breakingly hopeful. It’s so vivid she can no longer find that inner voice that was hers, all hers, separate from every grieving voice that threatened to depress her, every story she couldn’t shake off. As a child, she would play games where she tried to silence her inner voice, which was fun because it was practically impossible. She had wondered about her own internal voice a lot as a child, and investigated its origins with light-hearted wonder. Now, as an adult, she had forgotten about those musings until she couldn’t find herself anymore, until (in dreams) the impossible drowned her in recurring nightmares.

In the dream, she pushed aside the tablecloth to run from some impending threat. She tried to climb underneath the table to hide. Instead, she found the spinning, clicking gears of a clock rotating at different speeds. She gripped the tablecloth with both hands and tore it away as hard as she could. Her arm muscles tightened all the way to her shoulder, and with the violence of her efforts the whole kitchen itself was torn away. It was her against an unending wall of clockwork, a matrix of connections forged by gears and bolts. And she couldn’t leave. Not until she woke up.

Every morning that she wakes up, she understands. Her subjects, her victims, are each a gear in the greater clock of life. That’s why she can’t stop. If she had any hope of finding meaning in this life she had to keep adding gears to her clock, like filling in a beautifully detailed, intricate painting with several small and colorful dots. And what were humans if not gears in the cog of life? Aziza had learned that it was possible not to cherish life when someone failed to cherish her’s. But he was in jail now, far away from her vision. And Aziza had this deity of her own. A huge, talismanic secret she could never tell her mother, because surely the hag would pick it apart and analyze it and divest it of its spiritual meaning. Humans, after all, had lost any meaning to her. She felt no love for anyone or anything. It was only through silence and watching their activity that anything held meaning.

If she was going to save her own life, she would be the owl. It was the only thing she wanted to do anymore.

0 notes

Text

“No relationship can truly grow if you go on holding back. If you remain clever and go on safeguarding and protecting yourself, only personalities meet, and the essential centers remain alone. Then only your mask is related, not you. Whenever such a thing happens, there are four persons in the relationship, not two. Two false persons go on meeting, and the two real persons remain worlds apart.”

— Osho, Intimacy: Trusting Oneself and the Other

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

males whose first sexual experiences involved them assaulting other people have begun a life cycle of love n sex that involved rot n torture right out the gate and i hope it swallows you someday

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“She who looks with the look that recognises, that studies, respects, doesn’t take, doesn’t claw, but attentively, with gentle restlessness, contemplates and reads, caresses, bathes, makes the other gleam. Brings back to light the life thats been buried, fugitive, made too prudent. Illuminates it and sings it its names.”

— Hélène Cixous, from Coming to Writing and Other Essays

951 notes

·

View notes